1. Input Processing and the First Noun Principle

VanPatten’s (

1996) input processing theory argues that L2 learners’ attention to incoming input is limited, causing processing problems. Input provides crucial data for our processors which is accommodated into the system through form-meaning connections and appropriate parsing when it comes to syntactic features. The input processing theory specifically explores the psycholinguistic strategies used by L2 learners to derive intake from input. Input is the language that L2 learners hear and read and has a communicative intent. However, not all the input is processed. L2 learners process only a small portion of the input (intake) due to the use of processing strategies. VanPatten asserts that L2 learners may rely on default strategies that hinder efficient input processing. Therefore, modifying how L2 learners process input could influence both the quality and quantity of intake, and subsequently affect language development.

The input processing theory’s core assumptions are reflected in its two fundamental principles. The first principle, called The Primacy of Meaning Principle, suggests that “learners process input for meaning before they process it for form” (

VanPatten 2004, p. 11). The second principle is known as The First Noun Principle and suggests that “learners tend to process the first noun or pronoun they encounter in a sentence as the subject” (

VanPatten 2004, p. 22). In the case of English causative constructions, L2 learners are inclined to assign the role of agent to the first element encountered in a sentence. This ineffective processing leads to a delay in the acquisition of the linguistic feature as L2 learners misinterpret the meaning of the sentence. For instance, in the sentence “

Jenny had her bike repaired”, L2 learners are likely to think that it was

Jenny who repaired the bike.

2. Structured Input Activities

The main aim of structured input activities is “to alter the processing strategies/principles L2 learners take to the task of comprehension and to encourage them to make better form-meaning connections and/or parse syntactic features correctly” (

VanPatten 1996, p. 60). There are two types of structured input activities: (i) Referential; (ii) Affective.

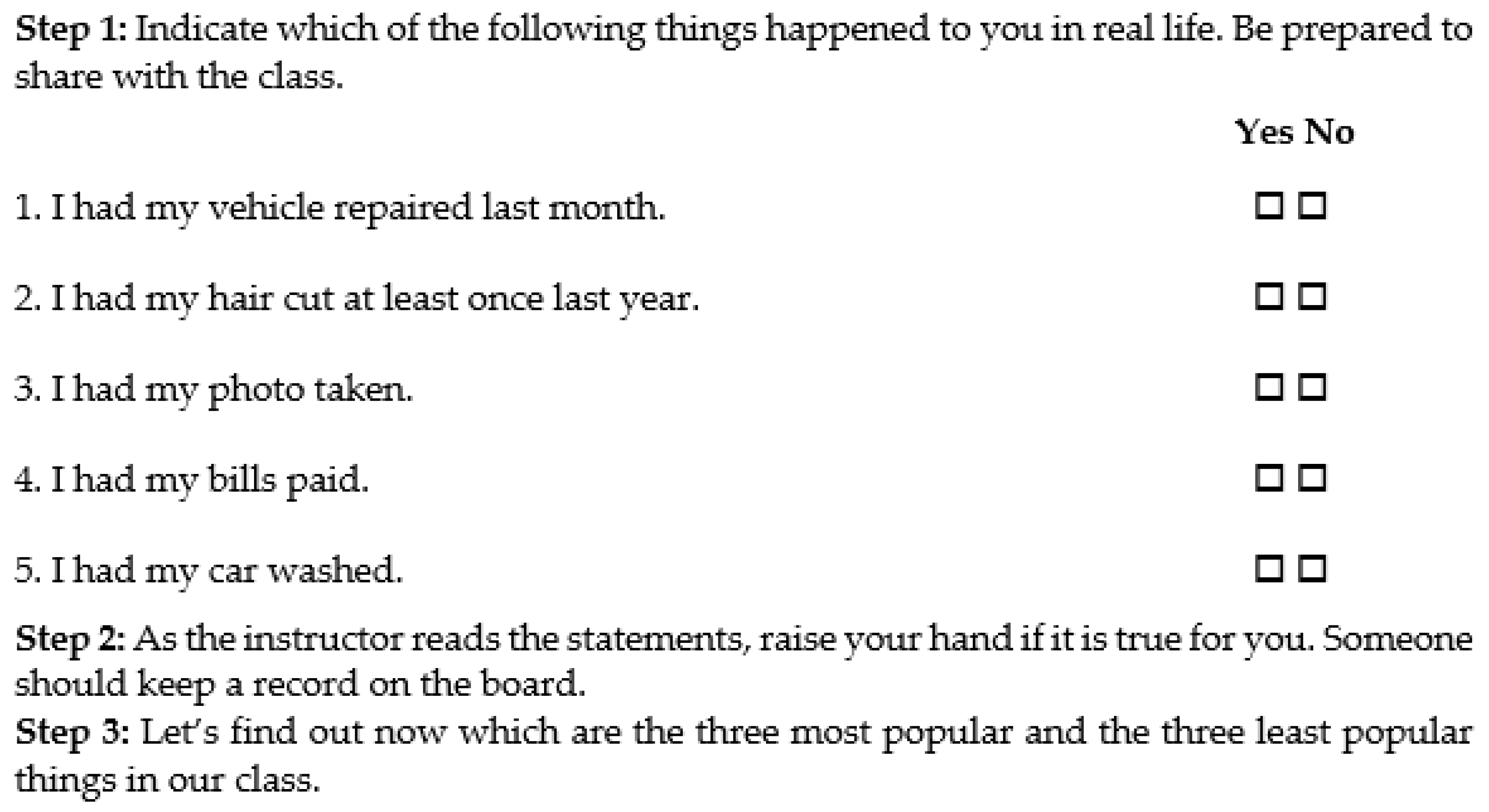

Referential activities force L2 learners to focus on a form and its meaning at the same time. Referential activities are ones where L2 learners must, for example, match a picture to an utterance in the target language. These activities are usually written or oral ones. Feedback is provided, indicating whether the answer is right or wrong.

Affective activities usually follow the referential activities and encourage L2 learners to interpret the message they hear or read by engaging them in activities in which they might need to express an opinion, or a belief, or provide other affective responses. According to

VanPatten (

1996, p. 170), affective activities reinforce form-meaning connections established during referential structured input practices.

Wong (

2004) argued that affective activities might either reinforce form-meaning connections or intensify the representations of form set in referential activities by providing more chances to engage with the target feature.

Farley (

2005) suggests that using a combination of referential and affective activities is the most effective use of structured input practice. Structured input activities aim at making L2 learners interpret and comprehend the linguistic feature in oral and written forms without producing it. Metalinguistic feedback is not provided during structured input practice.

4. What Are the Effects of Referential and Affective Activities?

There is little research comparing the relative effect of the two types of structured input practice: referential and affective activities.

Marsden and Chen (

2011) conducted a classroom-based experiment to compare the effects of referential and affective activities on the acquisition of the English past tense inflection for regular verbs -

ed.

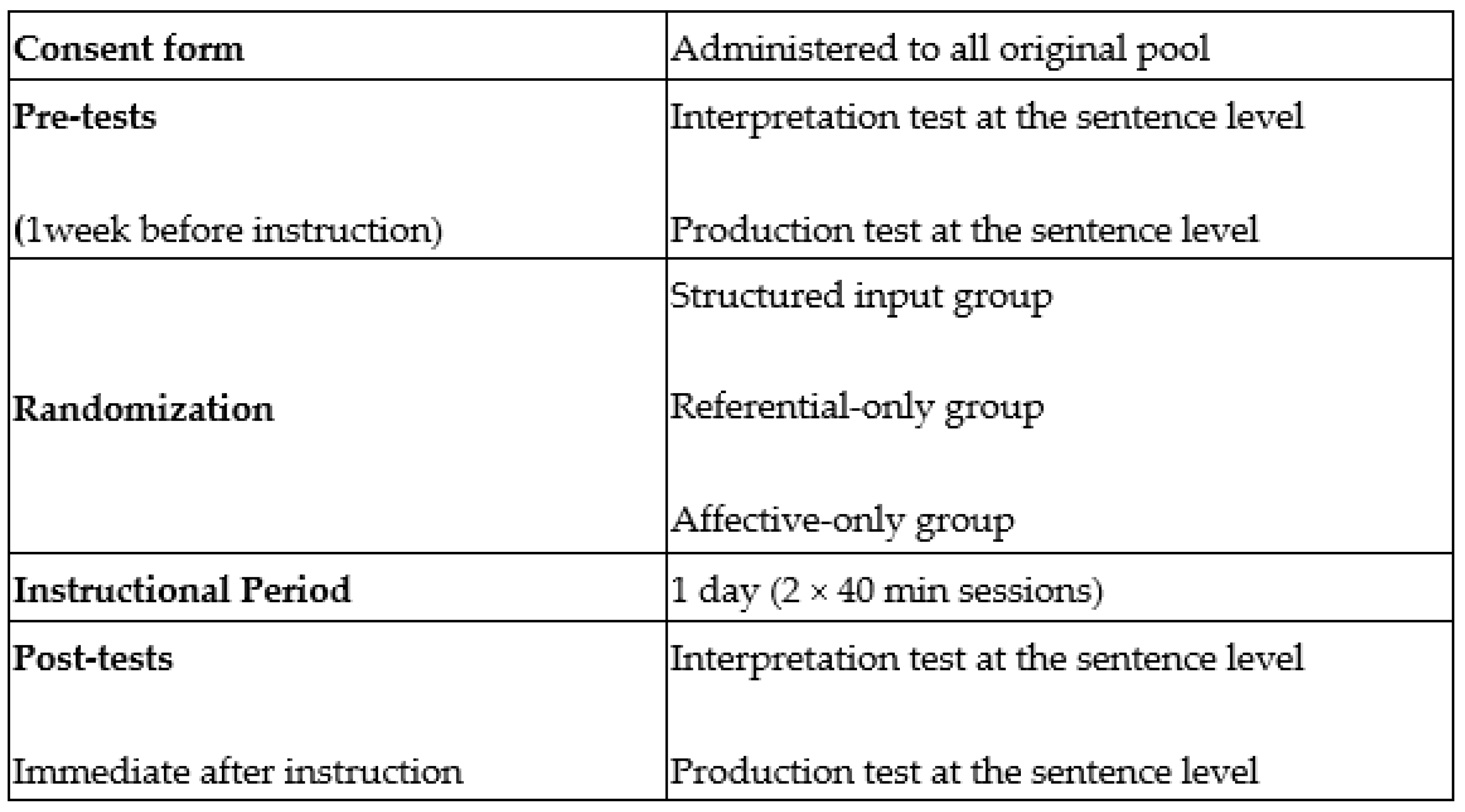

A pretest-posttest design was adopted. Participants were assigned to four groups: structured input, referential-only, affective-only, and a control group. Structured input group and referential-only group gained similarly substantial learning outcomes, while the affective-only group made almost no improvement from pre-test to post-test. No conclusions about the effect of isolated referential activities or isolated affective activities can be drawn based on

Marsden and Chen’s (

2011) study, since the referential + affective group encountered items with the target form at double the rate of the referential only group and the affective only group. One of the interpretations of the results is that only referential activities are needed to bring change in the processing system. Unfortunately, another shortcoming in Marsden and Chen’s study is the fact that they only tested for explicit knowledge of a rule. Therefore, the fact that they found affective activities did not help L2 learners could be because they did not account for how to test processing change through interpretation tasks.

Henshaw (

2012) also investigated the relative effects of structured input activities, either in combination or in isolation, on the recognition and interpretation of the Spanish subjunctive. Participants were assigned to three groups: full structured input group (referential + affective activities); referential-only group; and affective-only group. A pre-test, immediate post-test, and delayed post-test were administered to assess the effectiveness of the instructional treatments. The findings in

Henshaw’s (

2012) study suggested that structured input, referential activities, and affective activities facilitated the acquisition of the Spanish subjunctive in an equal way. The results of this study indicated that the two groups that engaged in affective activities were able to better maintain learning gains over the span of two weeks than the group that received only referential structured input activities as measured via an interpretation test.

Robayna (

2020) examined the effectiveness of the different aspects of the instructional intervention of processing instruction (referential versus affective activities). Participants in this study received instruction with either referential only, affective only, or referential and affective in combination. A control group received no instruction. This study adopted a pre-test, immediate post-test, and delayed post-test experimental design in examining the effectiveness of instruction on the interpretation of different word order sentences and present and past tense morphological sentences. A self-paced reading task was also developed in this study to measure online effects. The results from the sentence interpretation test, for both word order and morphology, revealed that the referential affective group made the most gains and maintained them a week later. The referential only group made gains and maintained them only on the word order study. The affective only group did not make any gains with either the word order or morphology. In the self-paced reading test, only the referential group showed a change in processing for grammatical and ungrammatical sentences within the word order sentences.

5. Motivation of the Present Study

In reviewing the studies investigating isolated or combined effects of referential and affective activities, it seems that there is still yet to be a verdict as to whether affective activities play a role in input processing.

Marsden and Chen (

2011) showed that even in attempting to maintain a task-essential element within affective activities, it was the referential activities that contributed to the learners’ gains rather than the affective activities. A limitation in this study is the fact that they tested only explicit knowledge.

Henshaw (

2012) showed affective activities to be responsible for the learners’ gains. In

Robayna’s (

2020) study the referential group made gains and maintained them only in the correct processing of word order sentences.

It is hard to compare the results obtained between

Marsden and Chen (

2011),

Henshaw (

2012), and more recently

Robayna (

2020) and draw any definitive conclusions. Similarly to

Marsden and Chen (

2011),

Henshaw (

2012), and

Robayna (

2020), the present study measures any potential difference between referential and affective activities. The research database exploring the isolated and combined effects of referential activities and affective activities is limited to few studies, and the results are mixed. In addition, it would be important to ensure that these effects are measured using participants from different backgrounds and ages. The Age Hypothesis argues that this treatment (structured input) would be equally effective with younger learners as well as it is with older learners (

Benati and Lee 2008, p. 174).

The main purpose of the present study is to compare the effectiveness and role of structured input referential and affective activities on the acquisition of English causative forms and to provide additional insights into the current debate on the role and effectiveness of referential and affective structured input activities. The specific research questions that guide this study are the following:

Q1: Which type of structured input activities (referential or affective) bring the most improvement in the interpretation of English causative forms at the sentence level?

Q2: Which type of structured input activities (referential or affective) bring the most improvement in the production of English causative forms at the sentence level?

7. Assessment

Two tests at sentence-level were developed for this study (interpretation and production). It was decided that the interpretation test was administered before the production test.

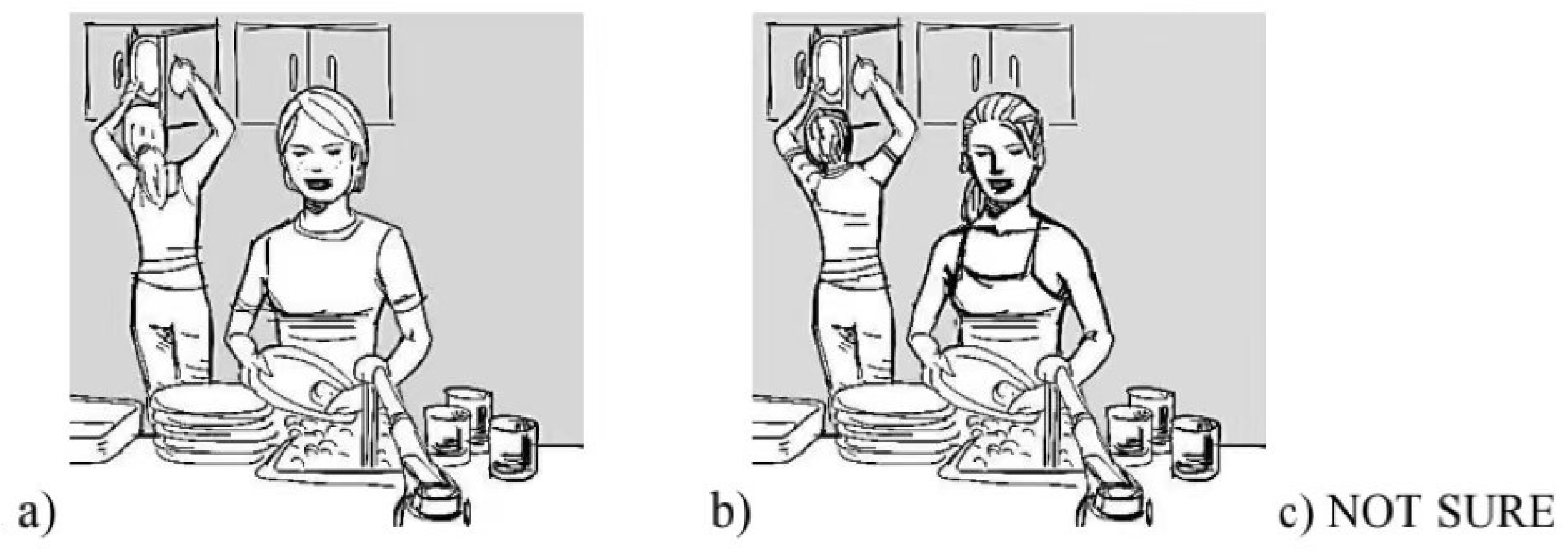

The interpretation tests consisted of twenty sentences, with ten distracters and the other ten target items. Target items chosen for the test were different than the ones used for the treatments. Each of the sentence was read aloud to the participants just once at a regular speed to gauge their immediate response to the auditory input. The participants were required to determine who was carrying out the action and select the corresponding image or choose “not sure” (see sample in

Figure 4).

To determine the performer of the action described in each sentence, please choose either option a or b, or choose “NOT SURE” if it is unclear who the agent is. (对于每个句子,请选出执行所描述动作的人物。可以选择a 或者b;如果你无法确定代理人是谁时,请选择“不确定”。)

Figure 4.

Sample item of the sentence-level interpretation test.

Figure 4.

Sample item of the sentence-level interpretation test.

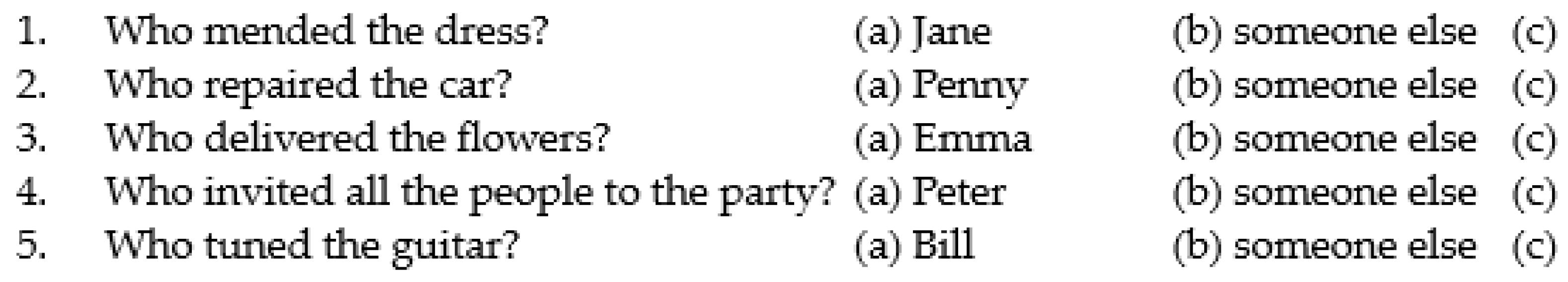

A sentence-level production test was also designed for this study to measure possible effects of the treatment on L2 learners’ developing system (see sample in

Figure 5). Although participants were not required to produce the target feature during the treatment received, a production test was used in this study to measure the competence of learners to assess their internal system for production. This involved five sentences with blanks, four of which demanded the participants to produce the English causative, while the other one was a distracter. Participants were given a brief, coherent script with a missing part. They were offered the start of this sentence along with some hints. The main aim was for participants to finish the second sentence in a manner that preserved the script’s conveyed meaning. Only the target items were scored in the sentence-level interpretation test and the sentence-level production test. In the interpretation test, no point was given for an incorrect response and one point for a correct one. In the production test, each correct response earned two points, while no points were given for incorrect responses. On a few occasions, one point was given for using an incorrect verb form (such as opting for an infinitive over a past participle) while constructing the structure correctly.

Rewrite the second phrase in each of the following scripts using the words provided in parentheses to convey the same meaning as the previous phrase. You are allowed to make any necessary changes but must include the given words. However, you must not delete any words from the original phrase. (将以下文本的第二句使用括号中提供的单词进行改写,以传达与前一句相同的意思。您可以进行必要的修改,但必须包含给定的单词。但是您不能删除原句中的任何单词。)

Figure 5.

Sample of sentence-level production test.

Figure 5.

Sample of sentence-level production test.

8. Results

A one-way ANOVA was used on the pre-test scores from all tests to determine any prior knowledge of the target item and to ensure group homogeneity at the start of the instruction. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was adopted with “Treatment” as the between-subject factor and “Time” as the within-subject factor, comparing the pre-test to the post-test results. A subsequent post-hoc analysis was conducted to assess any differences in performance between the three types of treatments.

8.1. Sentence-Level Interpretation Data

A one-way ANOVA was performed on the pre-test scores. The results indicated that there were no statistical differences among the three groups prior to receiving instructions (F (2, 41) = 0.023,

p = 0.995). The descriptive statistics are displayed in

Table 1 and showed that the structured input group and the referential-only group improved from pre-test to post-test at accurately interpreting sentences containing the target feature. In contrast, the affective-only group did not.

The repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect for Treatment (F (2, 41) = 6.972, p < 0.0001); a significant effect for Time (F (1, 41) = 63.242, p < 0.0001); and significant interaction between Treatment and Time (F (2, 41) = 6.533, p < 0.0001).

Considering the statistically significant difference for Treatment, a Tukey post-hoc test was carried out to compare groups’ performance from pre-test to post-test. The results of the post-hoc test indicated no significant difference between the structured input group and the referential-only group (p = 0.900). They were both statistically better than the affective-only group (structured input > affective-only group, p = 0.011; referential-only group > affective-only group, p = 0.002).

8.2. Sentence-Level Production Data

A one-way ANOVA was conducted on the pre-test scores of the production test. The results (F (2, 41) = 0.694,

p = 0.560) suggested that there was no statistically significant difference among the three groups before instruction.

Table 2 displays the average scores and standard deviations of the three instruction groups for the sentence-level production test. The descriptive statistics indicated that the structured input group, and referential-only group made significant gains. However, the affective-only group made almost no improvement from pre-test to post-test.

The repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect for Treatment (F (2, 41) = 3.424, p = 0.020); a significant effect for Time (F (1, 41) = 43.444, p < 0.0001); and significant interaction between Treatment and Time (F (2, 41) = 3.807, p = 0.012).

The Tukey post-hoc test was carried out to compare groups’ gains from pre-test to post-test. The test indicated no significant difference between the structured input group, and the referential-only group (p = 0.910). They were both statistically better than the affective-only group (structured input > affective-only group, p = 0.026; referential-only group > affective-only group, p = 0.001).

8.3. Summary of Results

The two questions of the present study were as follows:

Q1: Which type of structured input activities (referential or affective) bring the most improvement in the interpretation of English causative forms at the sentence level?

Q2: Which type of structured input activities (referential or affective) bring the most improvement in the production of English causative forms at the sentence level?

The main findings from this study provide enough evidence to offer an answer to research question 1. Participants in both the structured input and the referential-only instructional groups improved their accuracy in the interpretation of causative English forms. The affective-only group did not.

In relation to question 2, the results of the sentence-level production test echoed the ones obtained for the sentence-level interpretation test in that the two instructional groups (the structured input and the referential-only group) equally improved from the pre-test to the post-test. The affective-only group did not.

9. Discussion and Conclusions

The present study compared the effects of structured input activities with those of referential and affective activities on learners’ interpretation and production of English causative forms.

Accuracy scores were used to measure sentence-level interpretation among the three instructional groups (structured input, referential-only, and affective-only). The data analysis confirmed that the structured input group and the referential-only group outperformed the affective-only group on the post-test. The two instructional groups equally increased in the accurate interpretation of English causative forms from the pre-test to the post-test. This is original evidence of the effectiveness of structured input in helping L2 learners to process syntactic structures. These results are consistent with previous findings obtained (

Marsden and Chen 2011;

Robayna 2020) which indicated that the referential-only group outperformed the affective-only group. As the common element among the two instruction groups is the “referential activities”, it can be concluded that “referential activities” might be the causative factor influencing the effects of structured input practice.

The results from the sentence-level production test showed that both the structured input group and the referential-only group improved from the pre-test to the post-test. The affective-only group made almost no improvement in the production of English causative forms. Once again, the structured input and the referential-only group shared a common element: the referential activities. It can, therefore, be inferred that referential activities are the causative variable for the improvement in the production of the target feature.

Based on the results of this study, we might conclude that practicing referential activities enabled L2 learners to interpret English causative forms accurately and enriched participants’ intake. The results from this experiment concerning the production test are consistent with previous findings (

Marsden and Chen 2011). Referential activities push learners away from non-optimal processing strategies, such as the First Noun Principle in the present study. Referential activities, by modifying how L2 learners processed input, might cause changes in their developing linguistic system so that learners can tap into that system to string together words to produce accurate English causative forms at the sentence level. More research should be conducted to further measure this claim.

Overall, the findings from the data collection in this study indicate the following:

Structured input and specifically referential activities are the causative factor in providing L2 learners with the ability to process language input more accurately and effectively. In the case of this study, L2 learners receiving referential structured input activities do not rely on the First Noun Principle when they need to accurately interpret sentences containing English causative forms;

Structured input and specifically referential activities might be the causative factor in providing L2 learners with the ability to produce sentences containing the target feature accurately. Referential activities facilitate the accommodation of new linguistic features into learners’ developing system. The evidence shows that L2 learners can begin stringing words to produce English causative forms at the sentence level, even though they are far from demonstrating consistent production accuracy. Further research is needed to generalise this claim;

The results of the present study provide further support for the Age Hypothesis (

Benati and Lee 2008). The participants in this experiment are school-age learners (12–13 years old). This hypothesis suggests that, no matter the age of the participants, structured input practice will be effective in helping L2 learners to process input more accurately and appropriately.

9.1. Pedagogical Implications

The present study makes some important contributions at the pedagogical level.

Firstly, the evidence that referential activities are the causative variable accounting for the improvement in the acquisition of the target feature in this study strongly indicates that these activities are essential in language instruction.

Secondly, structured input practice achieves two main goals: (1) It introduces learners to the language in a context that is both engaging and easy to grasp without overburdening them; (2) It grants L2 learners the chance to both process input and increase the level of intake.

Thirdly, the findings from this empirical study highlight the effectiveness of structured input practice in focusing simultaneously on form and meaning, paving the way for a pedagogical approach to focus on form that seamlessly integrates form and meaning.

Despite the observation that the affective activities are less effective than the referential activities, the main finding of this study should not be overly emphasized to suggest that affective activities are not effective. Affective structured input activities combined with referential activities further enhance the input for L2 learners and make the input more meaningful to them. Affective activities prioritize meaning over form, as they seek to prompt learners to respond in a real-life scenario and to draw on their personal experiences. More significant learning gains can be achieved through the combination of referential and affective activities in the long term.

Finally, the findings from this study emphasize that structured input alone can lead to gains in language learning without the need for explicit information.

In this study, the absence of explicit information on the grammatical structure under investigation in the structured input group and the referential group did not hinder progress, illustrating that explicit information is not necessary.

9.2. Limitations of the Study

There were four main limitations to this study. Due to the restricted teaching schedule at the school where the experiment was conducted, the treatment’s duration of approximately 80 min was shorter than the regular intervention duration found in other structured input studies (

Marsden and Chen 2011). A longer intervention period might have resulted in more significant gains.

The sample size, with less than 15 participants in each group, was relatively small, and no control group was set due to practical reasons. Engaging a larger number of participants in the experiment should be considered in future research as this limitation can affect the validity and the generalizability of the findings.

Another limitation to this study was the absence of delayed post-tests to assess retention regarding the acquisition of the target feature. Future research should include delayed follow-up tests to measure long-term effects.

9.3. Further Research

This current study has provided valuable insights and contributions to both theory and practice while also identifying unresolved questions that may be explored in future investigations.

Further investigation is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of the three instructional treatments as measured via an interpretation and production test.

In future research, the effects of the three instructional treatments should be measured using online tests to measure in-depth processing and implicit knowledge. In addition, the written test used in this study provided L2 learners with an opportunity to monitor their answers. To solve this issue, there are two ways to modify the administration of the tests. One way is to use oral tasks only, ensuring real-time responses are identified. The other way is to use online measurements, such as eye-tracking, to track spontaneous responses of learners.

Another aspect would be to replicate this experiment in other languages to see if the same patterns are confirmed. Other linguistic features should also be investigated to compare the effects among the structured input group, the referential-only group, and the affective-only group, as the complexity of the target grammatical structure may lead to different results.