In this section, we will compare our analysis to two previous analyses of the same pattern of data in order to highlight what we take to be the advantages of our approach.

4.1. González-Vilbazo & López’ Analysis

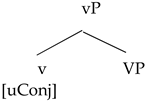

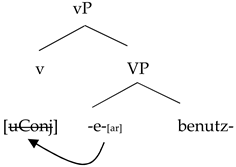

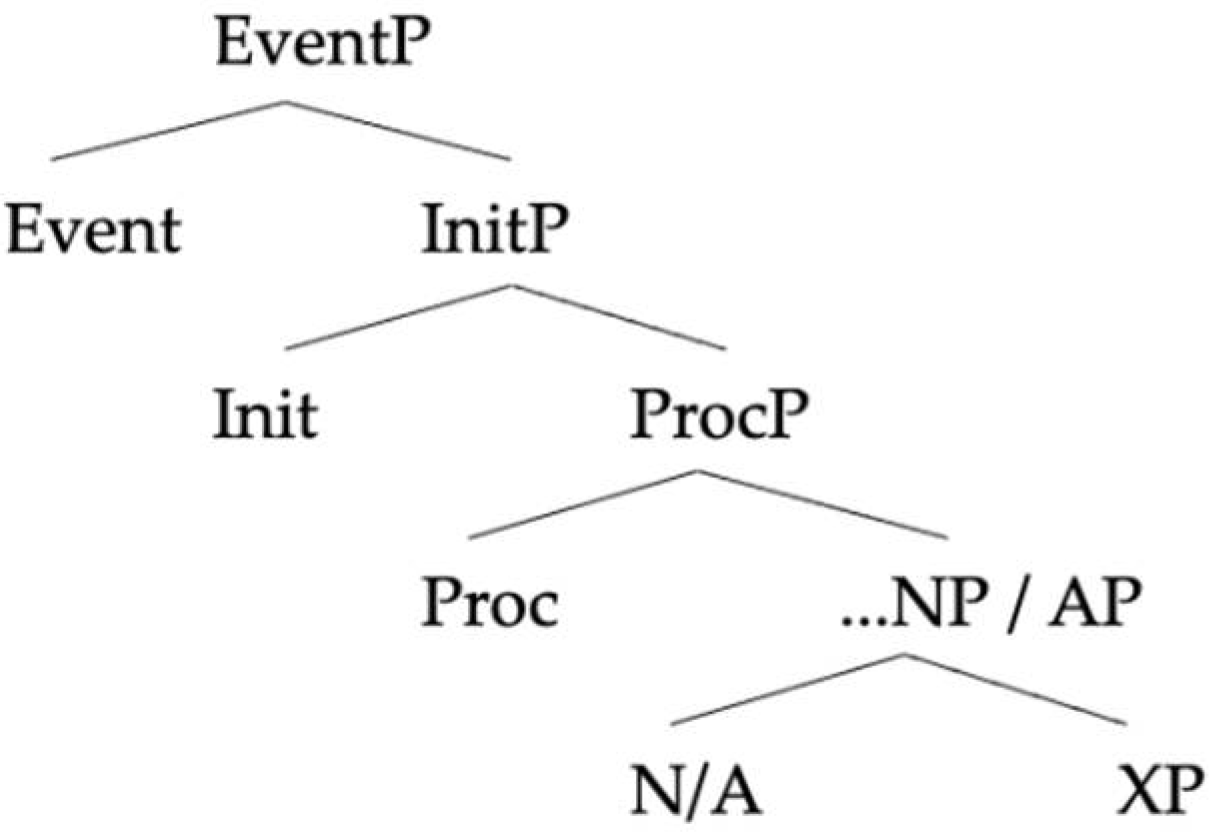

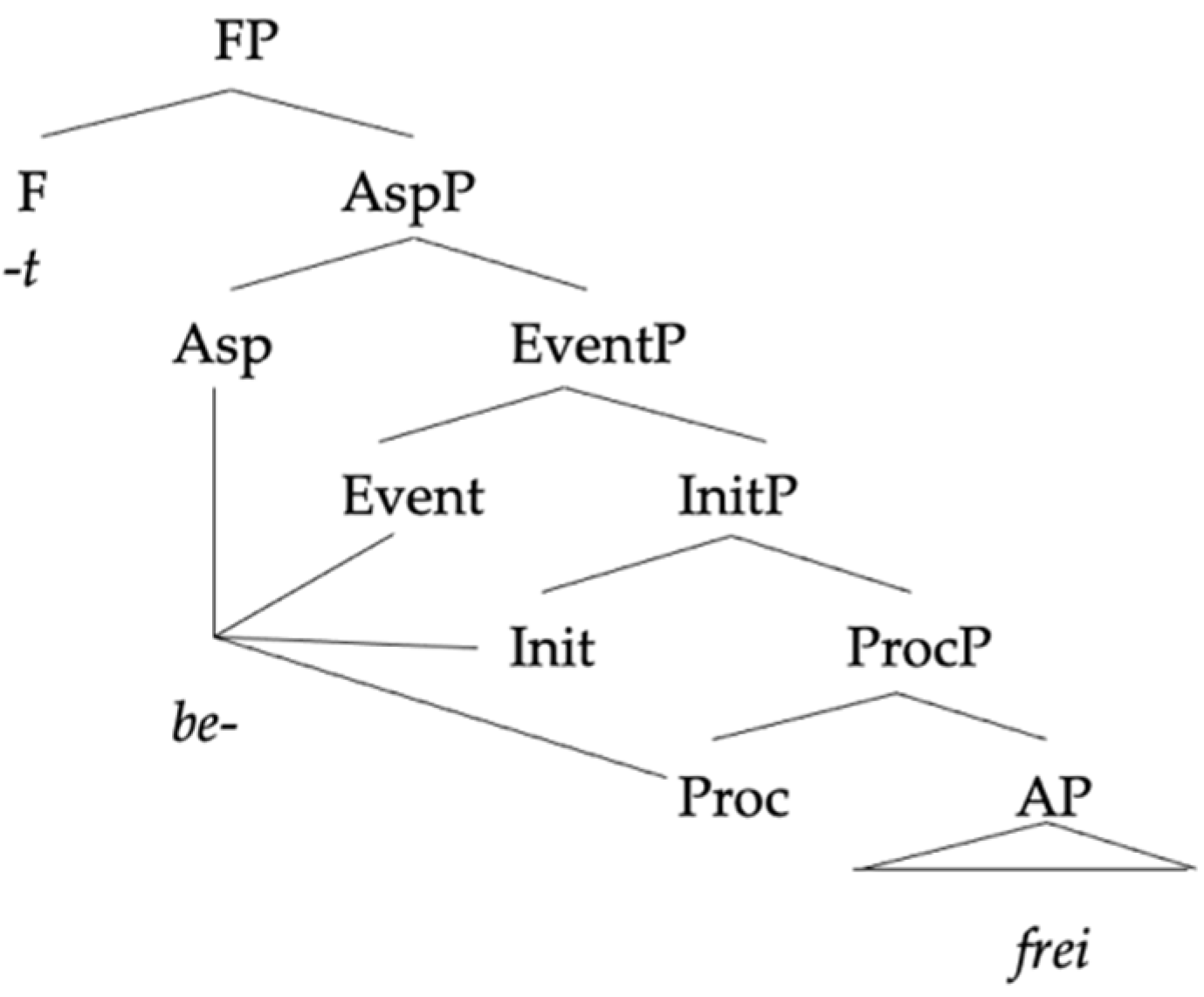

The above-discussed asymmetry is captured in

González-Vilbazo and López (

2011) as a mismatch between the information that the Spanish little v needs and the one provided by a German root. The analysis capitalizes on the fact that Spanish verb(alization)s compulsorily carry a theme vowel that associates the verb to a particular conjugation class—recall (6–7, in

Section 2.1, above). Thus, the Spanish little v is tagged with an uninterpretable feature [uConj] which needs to be valued by the base of the verb, which in the simplest case is a root. In contrast, the German little v lacks this feature, because German does not have conjugation classes—at most, verbs can be tagged for different types of irregularities, as in English or as would be the case independently for some Spanish verbs, regardless of class membership.

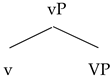

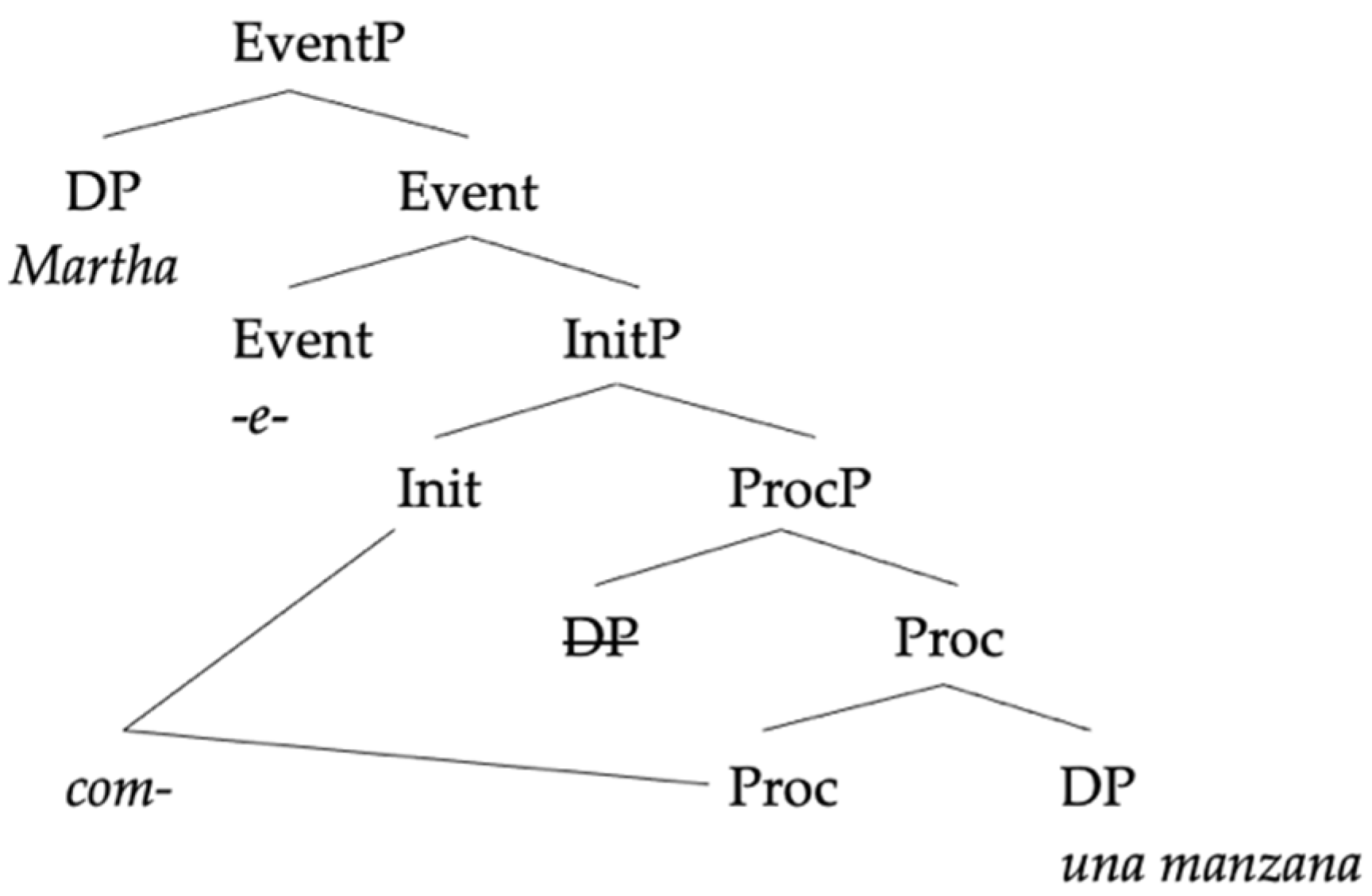

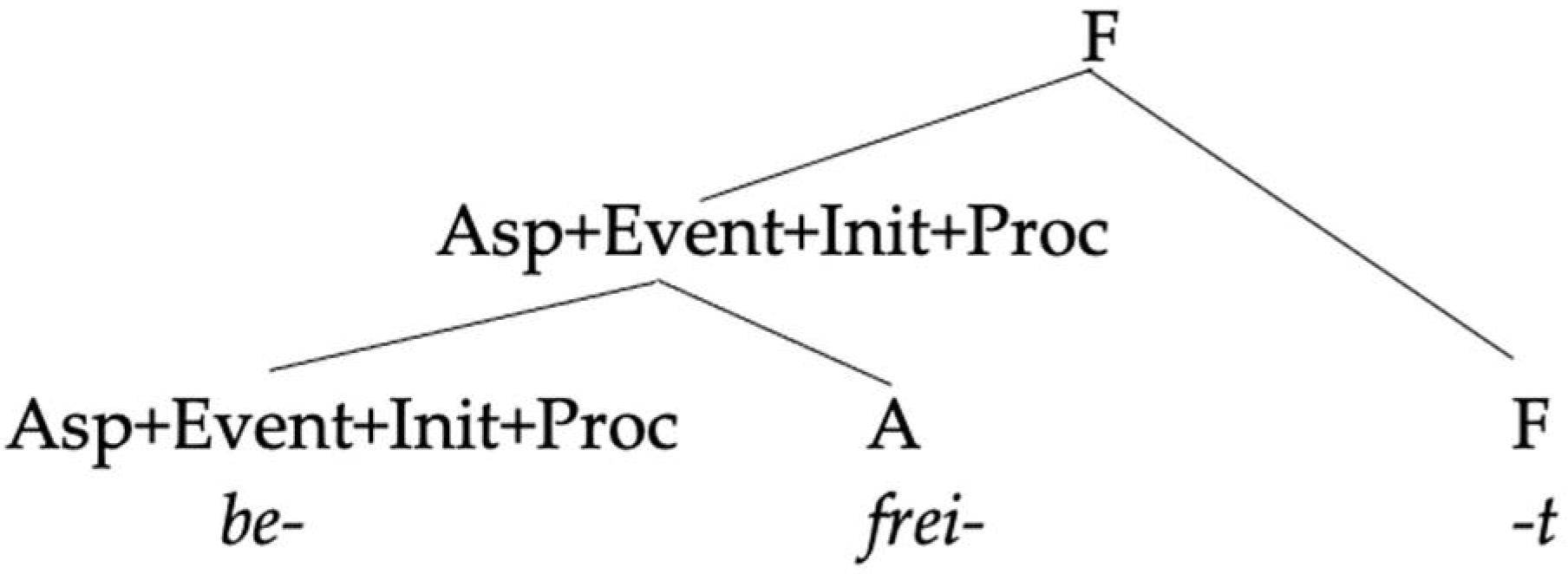

| (29) | a. | Spanish verbalization | b. | German verbalization |

| | | ![Languages 06 00167 i003]() | | ![Languages 06 00167 i004]() |

In this analysis, Spanish roots and German roots also differ in their feature endowment, in parallel with their respective little v heads. Spanish roots carry with them “a specification for conjugation class” which establishes a syntactic dependence with little v, “a goal with matching features” (

González-Vilbazo and López 2011, p. 841), therefore satisfying the requirement that a conjugation class is assigned to little v. German roots, conversely, lack this specification as their little v heads do not require a conjugation class.

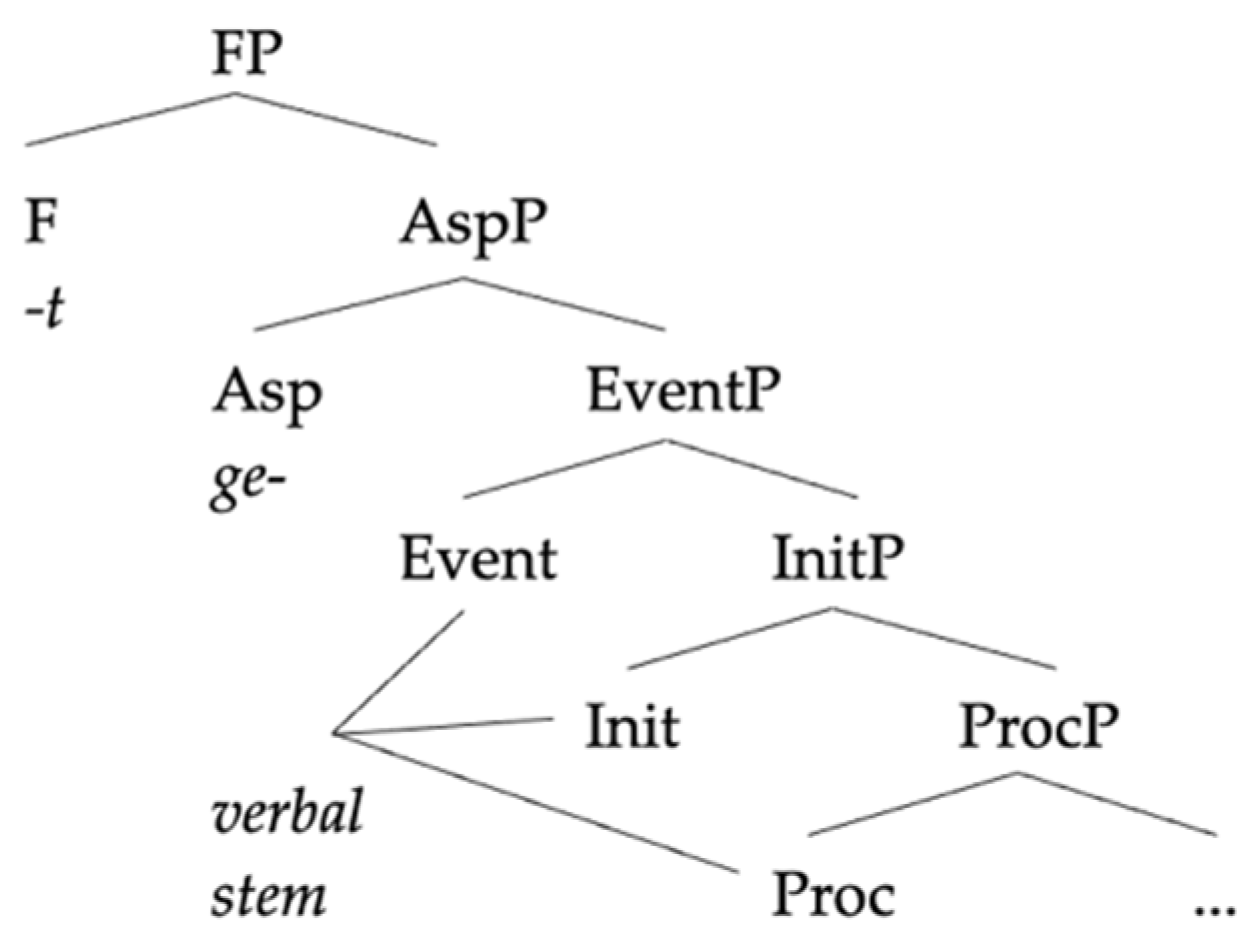

| (30) | a. | Spanish verbalization | b. | German verbalization |

| | | ![Languages 06 00167 i005]() | | ![Languages 06 00167 i006]() |

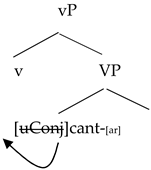

Starting from these assumptions, the mixture between the two languages can only go in one direction: a Spanish base combined with a German little v. A combination like (31), where the little v is Spanish and the base is German, keeps the uninterpretable feature of little v unchecked, triggering—under standard assumptions—a non-convergent derivation where the structure is transferred to the interfaces with active uninterpretable features.

| (31) | *[vP v[uConj] | [VP benutz...]] |

The opposite combination is, however, convergent (32): as the German little v does not require any conjugation class, there is no uninterpretable feature to check before transference. The base provides some interpretable information that is not used in the derivation, but as there are no unlicensed uninterpretable features, there is nothing formally wrong in the combination.

This is an elegant and simple account of the asymmetry. However, both empirical and theoretical reasons lead us to argue against one of its basic assumptions, namely that Spanish roots are tagged with a conjugation class. To the extent this is a problematic assumption, as we will argue, this analysis of the descriptive facts breaks down.

Our empirical argument has two parts, both pointing towards the same conclusion: when a base lacks a conjugation class in Spanish, the result is not ungrammaticality, but either addition to the base of a verbalizer that specifies the conjugation class or assignment of the base to the unmarked first conjugation. Thus, even if Spanish roots had a specification of conjugation class which German roots lack, the German root could have been combined with the Spanish little v by one of these two procedures.

Many studies about Spanish verbalizations have reached the same conclusion: when a base coming from a foreign language (most frequently now, English) is adopted in Spanish, one of the most common solutions is to combine it with a verbalizer—typically, but not exclusively -

e-a—to build its Spanish version (

Pratt 1980;

Romero 2010, among many others):

| (33) | to chat > chat-e-a(r), to blog > blogu-e-a(r), to format > format-e-a(r), to ban > |

| | ban-e-a(r)... |

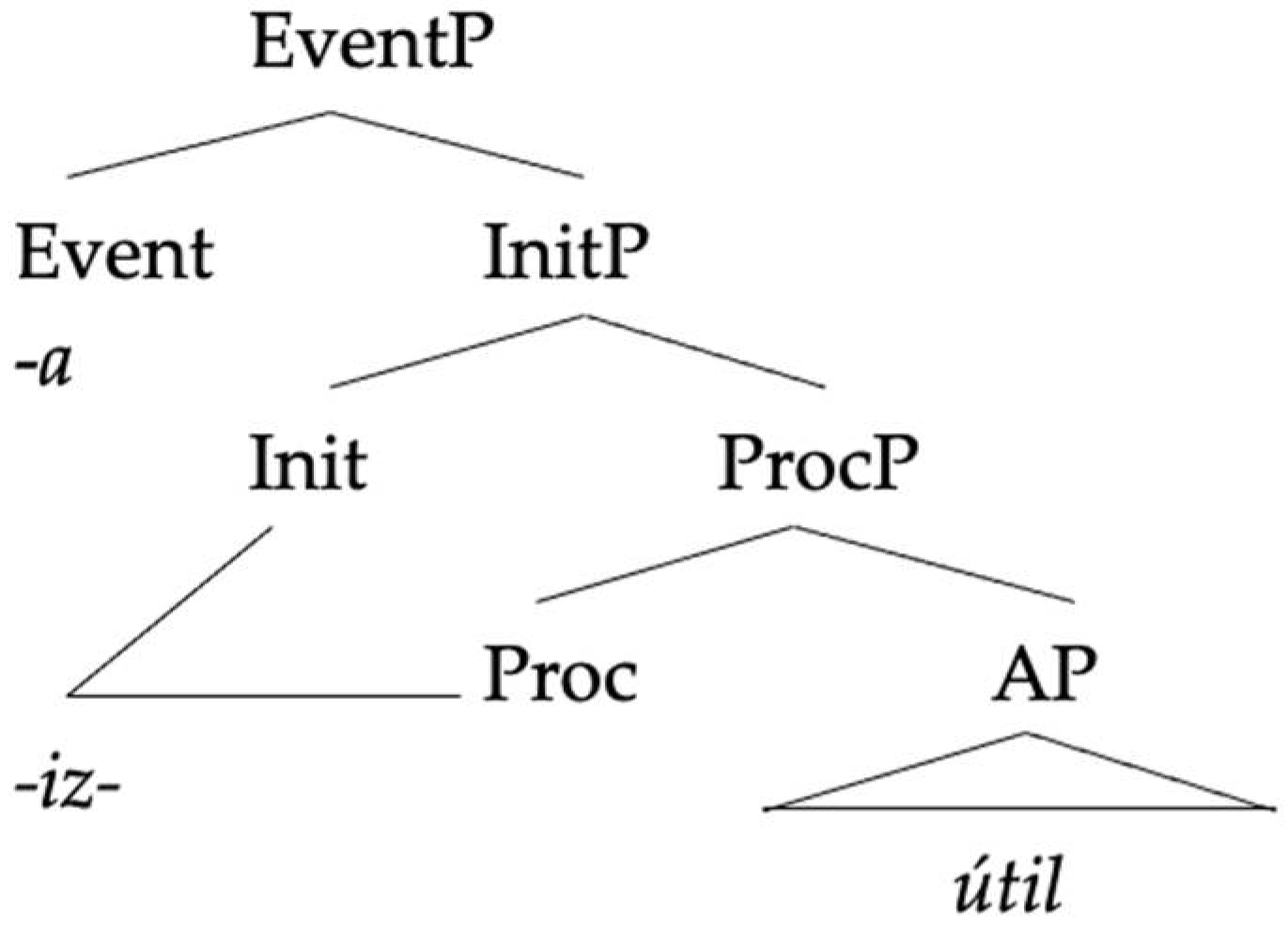

This solution—to add an overt verbalizer to the configuration when the root used—is foreign, but is in fact quite general in Spanish. Take for instance verbalizations from foreign proper names, as in (34). In the reasonable assumption that a proper name coming from another language is not assigned a conjugation class of its own, what Spanish does is to add the verbalizer -

iz- to these structures. The verbalizer -

iz-, in turn, is assigned to the first conjugation class.

| (34) | Trump > trump-iz-a(r) ‘to act like Trump/to do like Trump’, Bolsonaro > bolso |

| | nar-iz-a(r), Merkel > merkel-iz-a(r).... |

The question that we want to pose, from the perspective of González-Vilbazo and López’s analysis, is what prevents this type of solution for the German-Spanish mixtures, where the conjugation class is provided by a verbalizer. It is true that these authors explicitly say that they differentiate loanwords from code switching, but the difference proposed by them does not address the complication that we are noting. In our understanding of their analysis, borrowing involves copying a lexical item from one list (say, German) into a second list (say, Spanish), while code-switching involves introducing in the same numeration items from both lists, without previous copying in the other list (ibidem: 840–841). This might suggest that what

González-Vilbazo and López (

2011) have in mind for borrowing examples is that examples like (44) above have been copied into the Spanish list of lexical items, where they have been assigned a conjugation class. However, this would not work either: as we discussed in

Section 2.1, -

ea(r) is not one lexical item, but two, a segment corresponding to the verbalizer -

e- which imposes the first conjugation class, and the theme vowel corresponding to this conjugation class. Thus, the borrowings in (33) belong to the first conjugation class because they are verbalized by -

e-, not because their roots have been tagged with the first conjugation class. Tagging these roots with conjugation class information is either redundant or contradictory with the conjugation class specification of the verbalizer -

e-, depending on the class assigned to them. This makes it implausible that the roots have been tagged with that information at the same time they combine with a verbalizer. However, even if we assume that such information has been added to the root, a problem remains for

González-Vilbazo and López (

2011): once the base contains -

e-, that -

e- carries information about the conjugation class, and the derivation in (35) should be convergent, counterfactually.

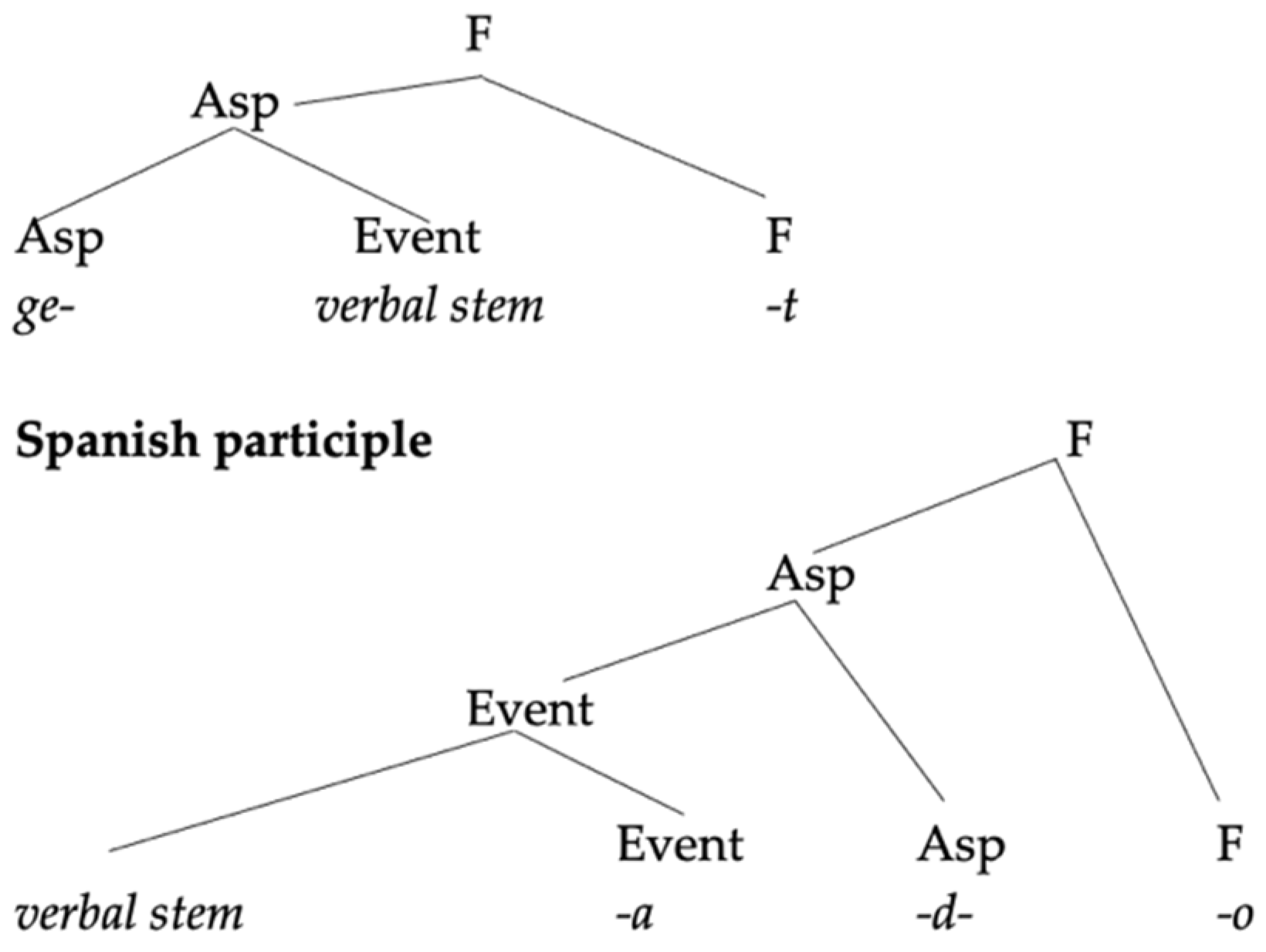

| (35) | Spanish little v, German root, Spanish verbalizer |

| | ![Languages 06 00167 i007]() |

In other words, if the ungrammaticality of the combination of a German root with a Spanish verbalizer was due to the conjugation class specification required by Spanish, as the authors do, the mixings should be possible once the German root combines with a Spanish verbalizer that already carries with it a specification of its conjugation class. From this perspective, it should not matter whether the root lacks its own specification or not.

The second empirical problem, in fact, is the claim that all conjugation classes must be specified within the root in Spanish. Let us assume, for the sake of the argument, that

González-Vilbazo and López (

2011) are right that Spanish roots specify their conjugation class. As we know, there are three conjugation classes in Spanish, but their status is very different.

RAE and ASALE (

2009) estimate that as much as 90% of Spanish verbs belong to the 1st conjugation, while the 2nd and the 3rd are dramatically less represented, are never used to adapt borrowings, and typically are mixed with each other in verbs of low frequency (e.g.,

tañir ~ tañer, ‘to toll’). These facts are reflected in some work, such as

Oltra-Massuet (

1999) for Catalan, which propose that the 1st conjugation is the unmarked one, also from the perspective of its feature endowment.

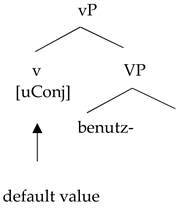

This opens a theoretical possibility, in fact: the first conjugation is the one assigned by default to bases that lack any specification of conjugation class. If that was the case, in fact, one would not obtain ungrammaticality when the Spanish little v does not find any specification for the conjugation class of the base. In a configuration like (36), the first conjugation class would be the value assigned by default to the unchecked [uConj] feature, similarly to

Preminger’s (

2014) claim about neuter gender being the default value assigned to unchecked gender features in many languages; instead of a non-convergent derivation, we would obtain a convergent derivation where unvalued features are manifested as default values.

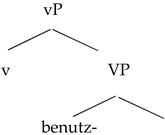

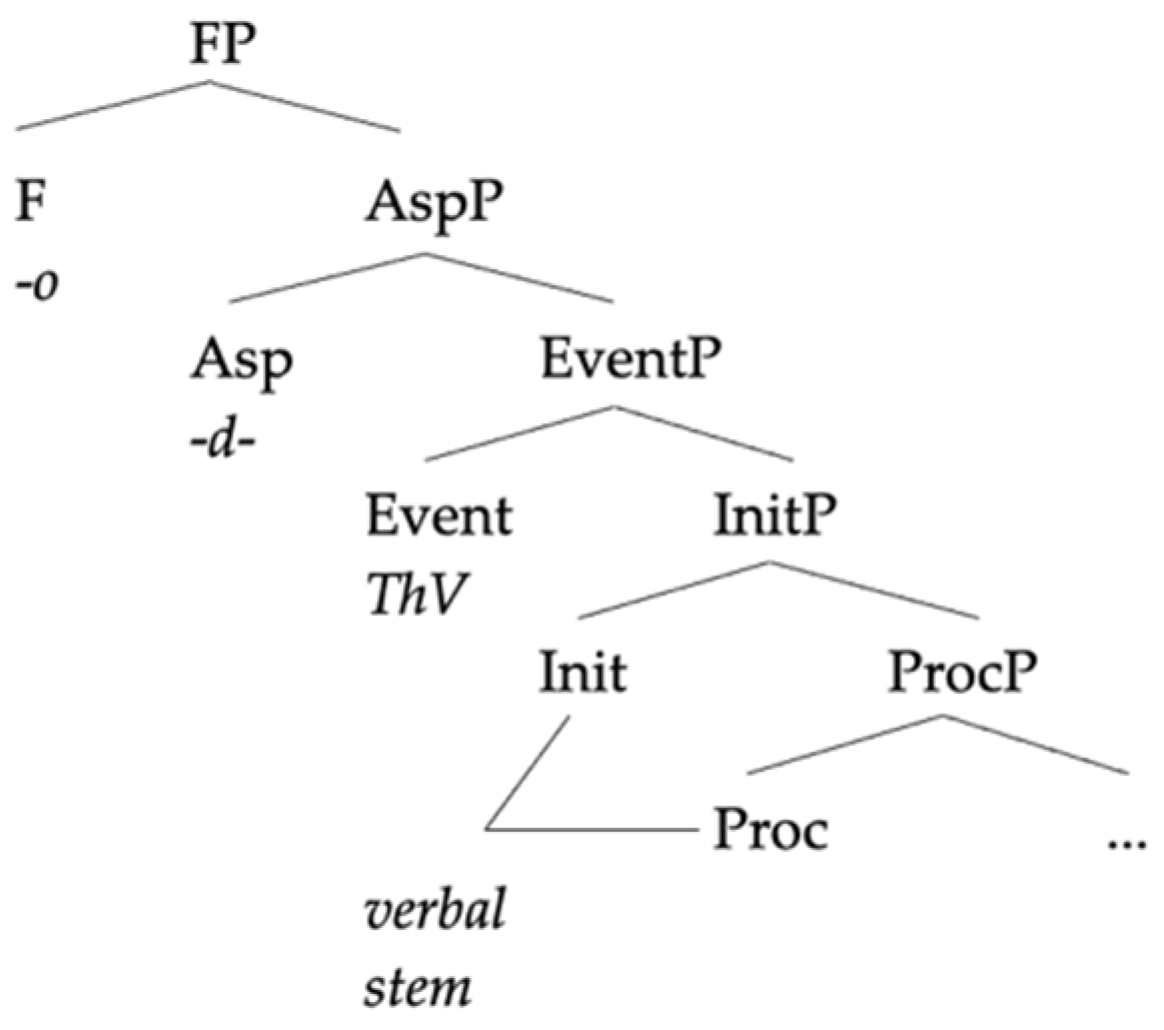

| (36) | Spanish little v, German base |

| | ![Languages 06 00167 i008]() |

There is, in fact, empirical evidence that the 1st conjugation is the one assigned in Spanish in contexts where there is no specification about the conjugation class. Our first piece of evidence comes from so-called ‘pentasilabismo’ verbs, which are verbs derived without any overt verbalizer from nouns or adjectives that display overt nominalizers or adjectivalizers.

| (37) | decep-ción ‘disappoint-ment’ > decepcion-a(r) ‘to disappoint’, apert-ura ‘open- |

| | ing’ > apertur-a(r) ‘to inaugurate’, influe-ncia ‘influence’ > influenci-a(r) ‘to in |

| | fluence’, explo-sión ‘explosion’ > explosion-a(r)... |

In these verbs, the only conjugation class used is the 1st. More generally, in fact, there are no verbalizations in Spanish, coming from any noun or adjective, where the verbalizer is null, and the conjugation class is the 2nd or the 3rd.

| (38) | a. | N-ø-a(r), *N-ø-e(r), *N-ø-i(r) |

| | b. | A-ø-a(r), *A-ø-e(r), *A-ø-i(r) |

We believe that this strong empirical generalization makes sense if the 1st conjugation in fact is viewed as the default manifestation of conjugation class and not as the result of lexical assignment. In the examples above, the base lacks any specification of conjugation class, being a noun or an adjective. The verbalizer is zero: if the first conjugation is assigned because the zero verbalizer specifies the 1st conjugation, then it becomes a lexical accident that there are no verbs from the 2nd or the 3rd conjugation with the shapes in (38). Instead, if the 1st conjugation is the default manifestation of the conjugation class, the pattern follows naturally. If one takes seriously the idea that a zero morpheme has morphosyntactic information but lacks morphophonological properties, its null nature must also mean that it lacks any specification for the conjugation class, meaning that the 2nd and the 3rd conjugation are excluded, and the 1st is assigned because it is the one used when there is no conjugation class that is specified.

Second, the theme vowel of the first conjugation is always the one to be found in the cases of nominalizations or adjectivalizations where the theme vowel is required by the suffix, and not imposed by the base. Consider the nouns in (39) and the adjectives in (40).

| (39) | a. | leñ-a-dor |

| | | wood-1c-er ‘someone that cuts wood’ |

| | b. | histori-a-dor |

| | | history-1c-er ‘someone that studies history’ |

| (40) | a. | alcald-a-ble |

| | | major-1c-able ‘that can become a major’ |

| | b. | ministr-a-ble |

| | | minister-1c-able ‘that can become a minister’ |

What is significant about these examples is that the bases cannot be verbs: *leñar, *historiar, *alcaldar, and *ministrar are unattested, in contrast to the nouns leña, historia, alcalde, and ministro. The bases are nominal, and the presence of the theme vowel is required by the final affix, which, respectively, derives agent nouns from verbs and modal adjectives from verbs. Our goal is not to analyze these cases, but simply to note that, once again, we have a configuration where the base is not verbal, precluding it from being associated to a conjugation class, and the result is not ungrammaticality, but assignment to the 1st conjugation.

From the perspective of

González-Vilbazo and López (

2011), this should mean that—if the problem for the asymmetry is the lack of a conjugation class specification in the base—Esplugisch should allow a German–Spanish mixture like *

benuzt-a(r), where in the absence of any specification for the conjugation class the 1st conjugation is used. As forms like

benutzar seem to be unattested, this is another problem for their proposal. Our final critique to

González-Vilbazo and López (

2011), admittedly, is less serious, because it is based on a theory internal contradiction that would be resolved if the theoretical framework were slightly modified. Nevertheless, in the theory adopted, roots should, like in

Marantz (

1997), lack any specification for grammatical category. Given that conjugation classes in Spanish are exclusive of verbs, it seems to us contradictory to say that an acategorial root specifies its conjugation class, because conjugation class presupposes a verbal status. In our view, it would be more internally coherent to adopt

Acquaviva’s (

2009) proposal that conjugation classes and, in general, the assignment of roots to specific morphologically relevant classes exclusive of one single category, should be viewed as the root being licensed only in the context of a functional head that carries the right specification. However, this view would mean that the root does not carry any interpretable feature for conjugation class, and that in fact little v would be the one assigning the root to one conjugation class, not vice versa, which if anything would predict that

utilisieren should be ungrammatical because the base

utilis- would need to be licensed under a 1st conjugation context that is not provided by the German verbalizer.

The above could of course be solved theory-internally in several ways available to the authors: perhaps what combines with the verbalizers in the relevant examples is always some intermediate verbal lexical category—recall that we have noted that in their examples there is more material beyond the root, see

Section 3.4, example (23)—, or maybe conjugation class should be viewed as a sub-categorical property that is manifested as noun class morphology when the root appears in a nominal context. For this reason, we do not take this final problem to be as serious as the previous two, which we believe make the wrong empirical predictions for the data analyzed.

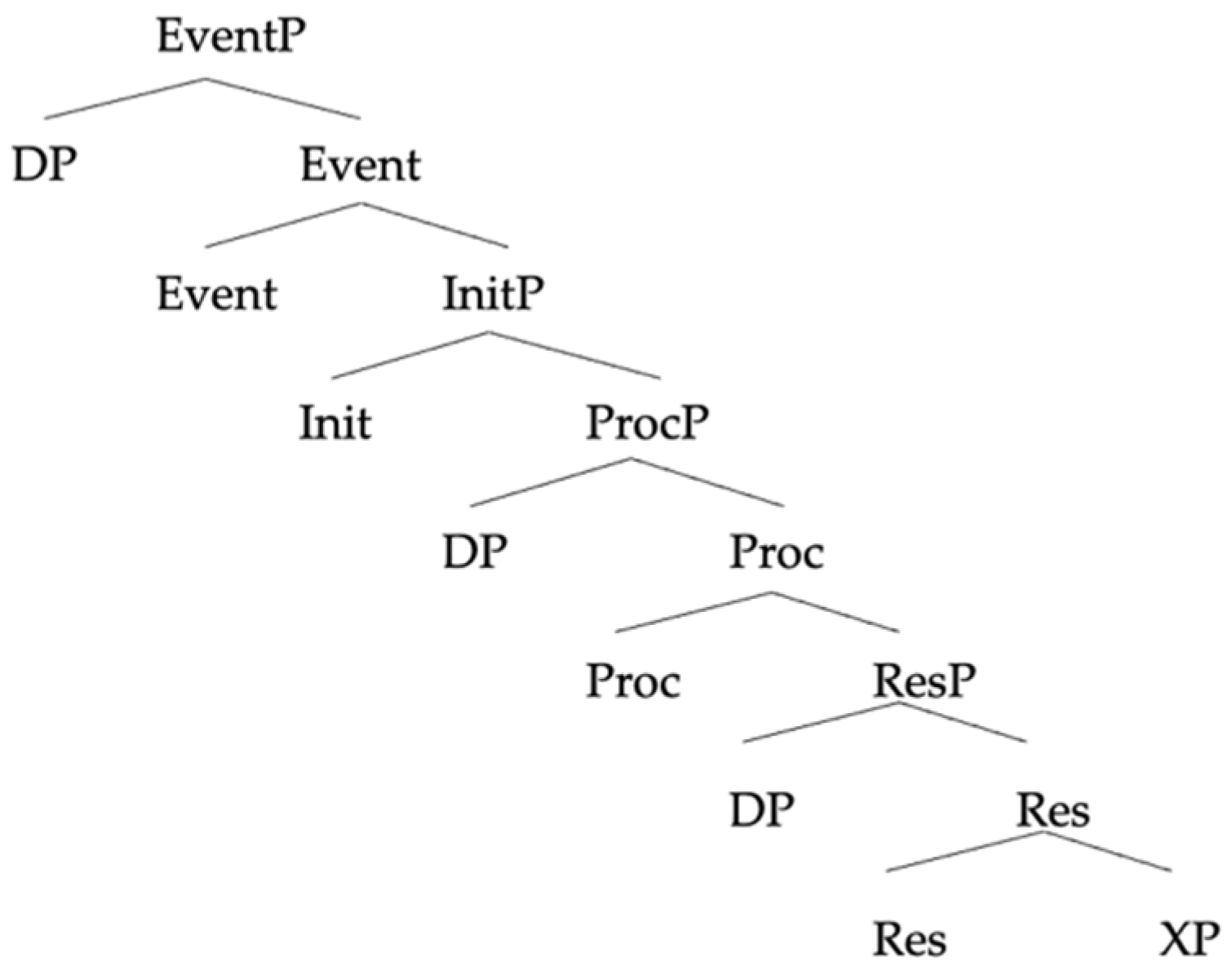

4.2. Alexiadou’s and Alexiadou & Lohndal’s Analysis

Like our own theory,

Alexiadou’s (

2017) and

Alexiadou and Lohndal’s (

2018) proposal is based on the nature of the exponents available in the German–Spanish pairs, but they adopt a view where the asymmetry in (1) follows from a preference for the unmarked or default realization of each morphological node: “Speakers pick the default/underspecified realization, if such a realization is available” (

Alexiadou and Lohndal 2018, p. 11). Specifically, their proposal is that in the asymmetry in (1) the German verbalizer emerges because it is the default manifestation of the verbalizing head, in their assumed notation little v.

This competition is determined based on the available V[ocabular] I[tem]s for the individual language pairs: -

isier- [is] the default realisation of v in the case of Spanish and German pairs, as Spanish has no overt realization of v that is salient enough for speakers to identify, unlike German (

Alexiadou 2017, pp. 186–87).

We see three main issues with this approach. The first one refers to the claim that Spanish has no overt realization of v, the verbalizing head. We take this claim to mean that, following

Oltra-Massuet (

1999), the theme vowel could be treated as a dissociated morpheme whose position of exponence is not represented syntactically. While it is true that Spanish must have a zero verbalizer only identifiable by the theme vowel, we have seen in

Section 2 above that Spanish has a robust set of overt exponents that correspond to the verbalizers and which come accompanied by theme vowels, among them -

iz-, -ific-, and -

ec-, so this claim is not strictly true unless interpreted in a much more restricted sense: the default verbalizer in Spanish happens to be materialized as zero, and is only visible by the addition of a theme vowel.

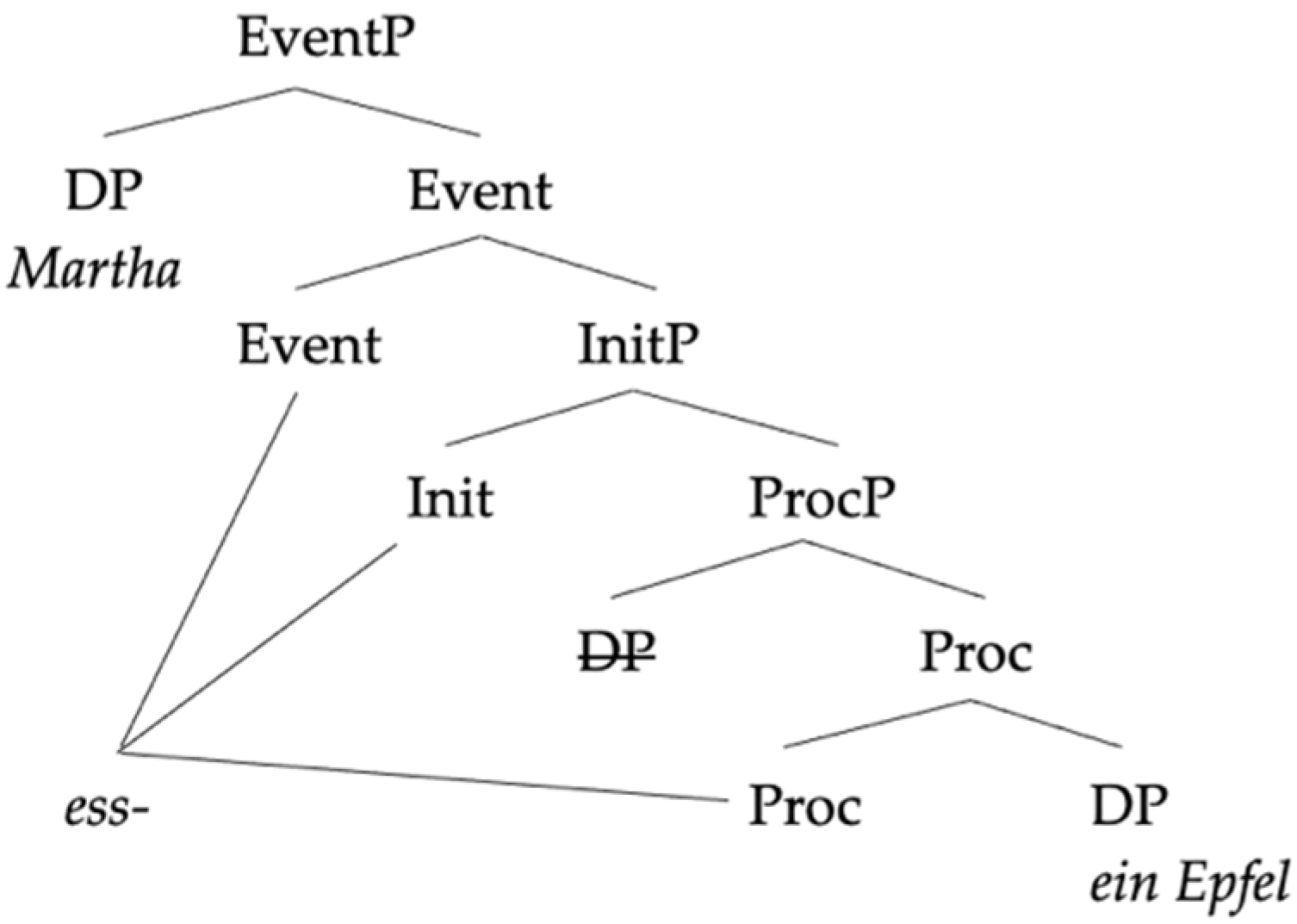

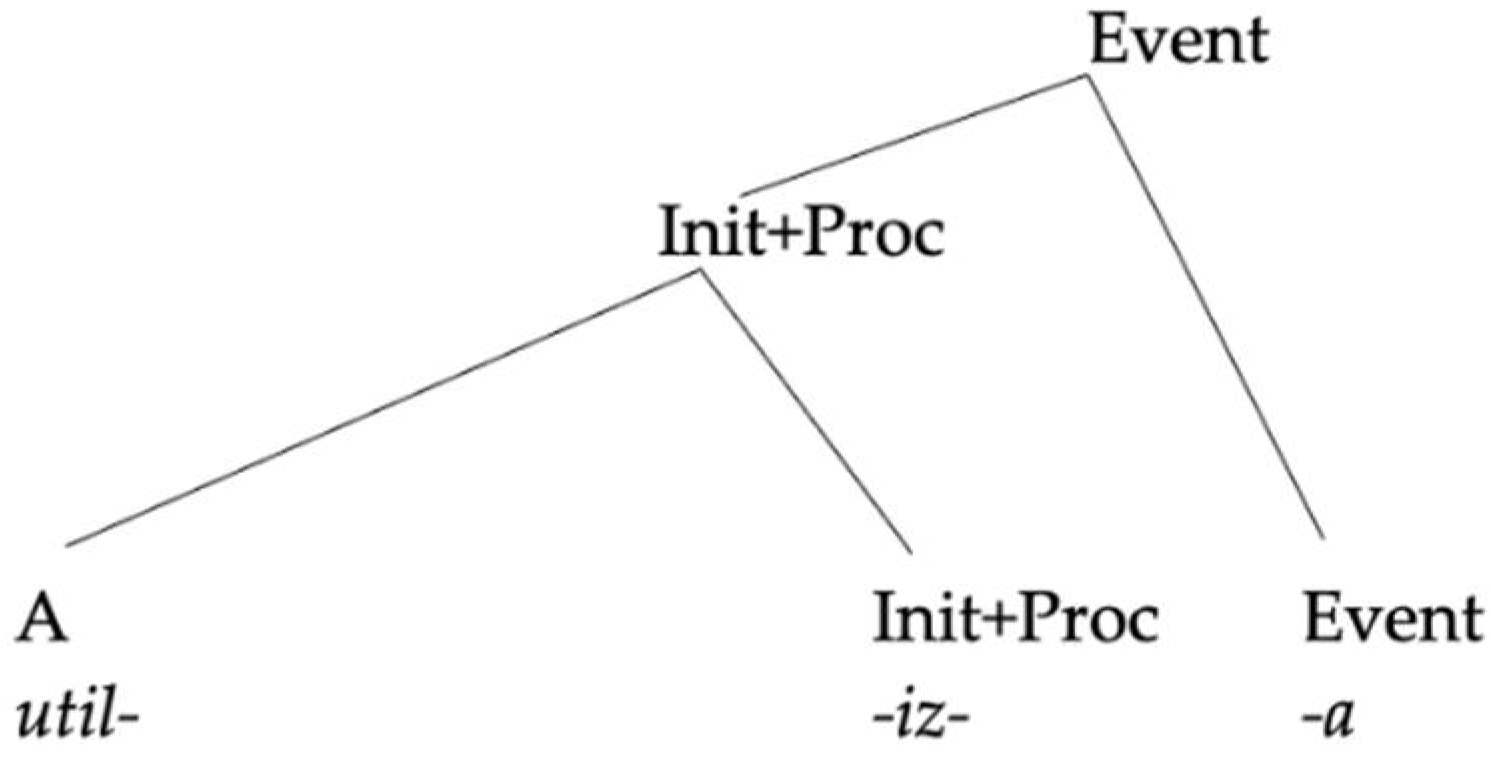

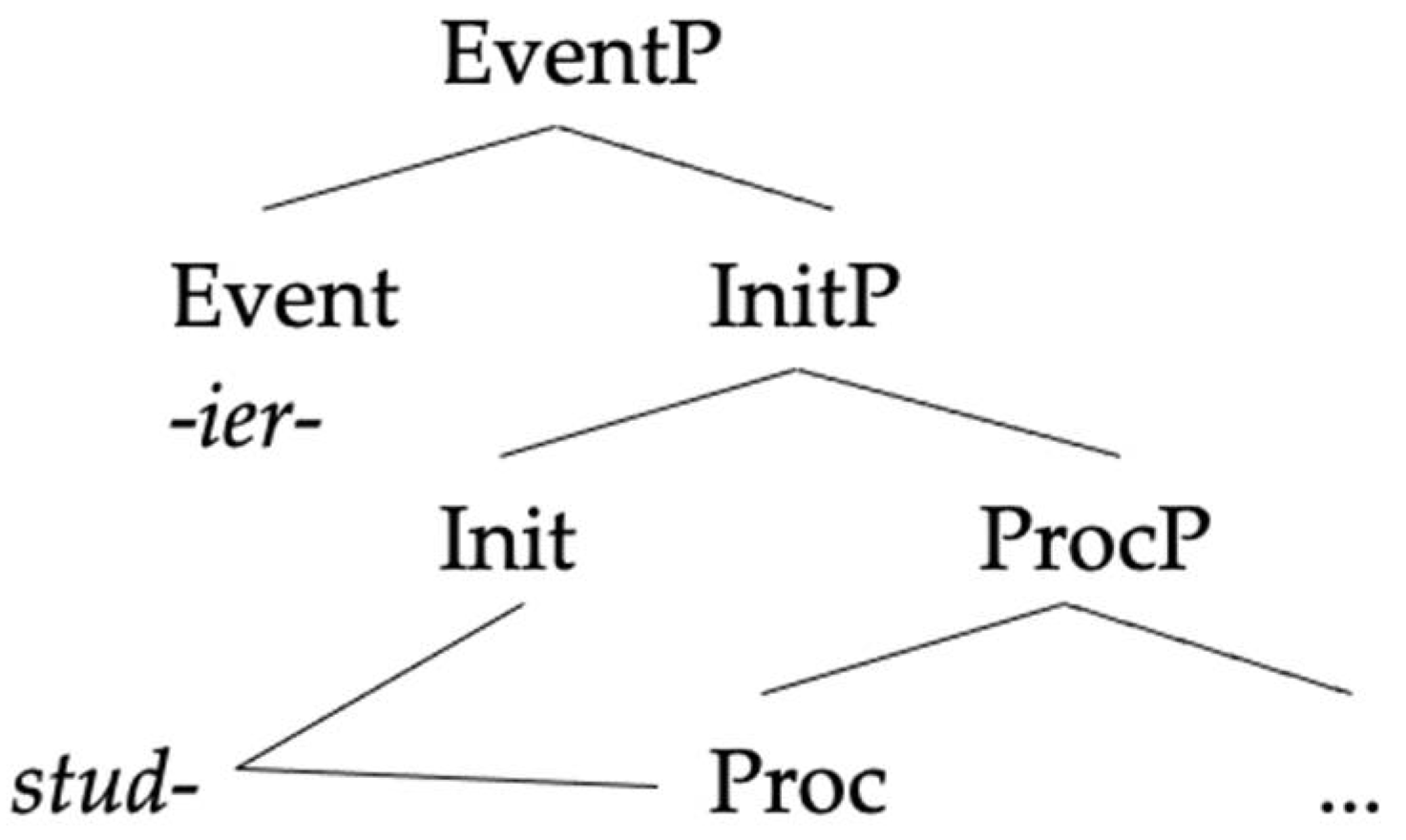

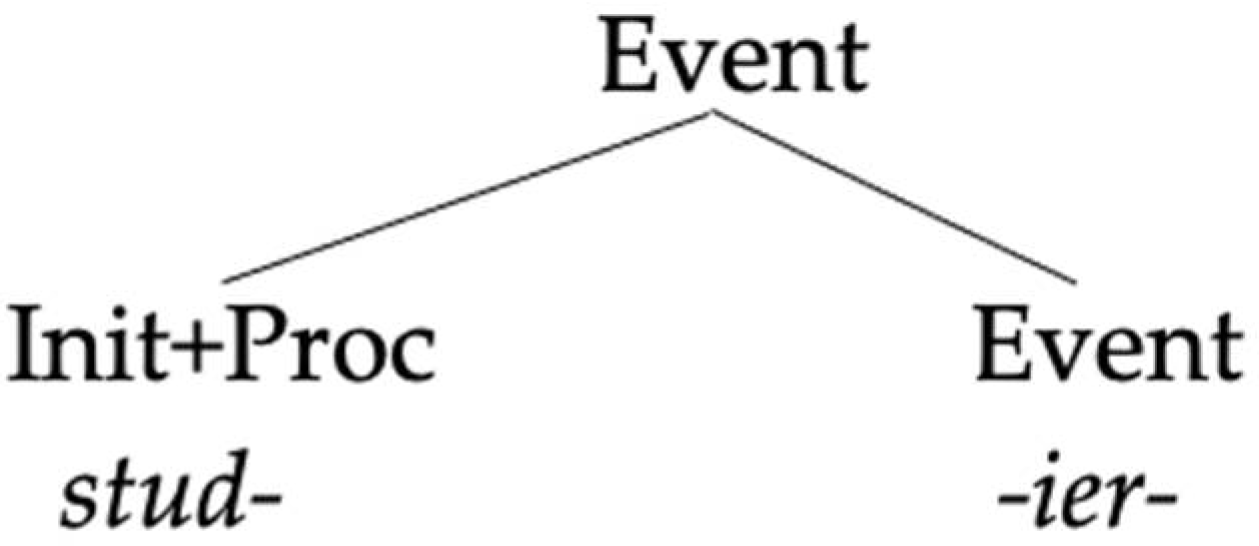

Let us, however, for the sake of the argument and fairness to their analysis, assume that both claims are true, that is, that theme vowels are not represented in syntax and that the default verbalizer in Spanish is zero. The problem is that the Esplugisch verbalizations mixing German and Spanish show either bases that were already verbs in Spanish or that contain some overt verbalizer, like -e(ar) or -iz(ar) in the seseante version, which shows that the competition cannot be happening between a Spanish and a German verbalizer in that context—simply because the base is already verbal, see (30) above.

It is true that in German -

isier- is a recognized allomorph of -

ier- (

DUDEN 2006, §1046) but considering the pattern of data provided by Esplugisch it is unlikely that the segmentation is as in (41a).

There are several arguments against (41a). The first one is that when the base is a Spanish verb that is itself morphologically simple, the suffix used is always -

ier-, never -

isier-. The data document

cos-ier(en), not *

cos-isieren, or

enter-ier(en), not *

enter-isier(en). Therefore, a segmentation like (41a) needs to explain why this form only appears precisely in cases where the base is not verbal. Second, segmenting like (41a) misses the generalization that the sequence -

isier- only appears precisely in forms that, in Spanish, would have carried precisely the verbalizer -

iz- and not any other verbalizer:

| (42) | a. | util-iz-a |

| | b. | aleman-iz-a |

Take, for instance, cabr-e-ier-en, from cabr-e-a ‘to annoy’. If the form -isier- were used by default, we would have expected *cabreisieren, which is not the case. These two facts strongly support a segmentation like (41b), where the segment -is- is part of the Spanish base, pace the absence of an interdental sound, thus corresponding to the verbalizer.

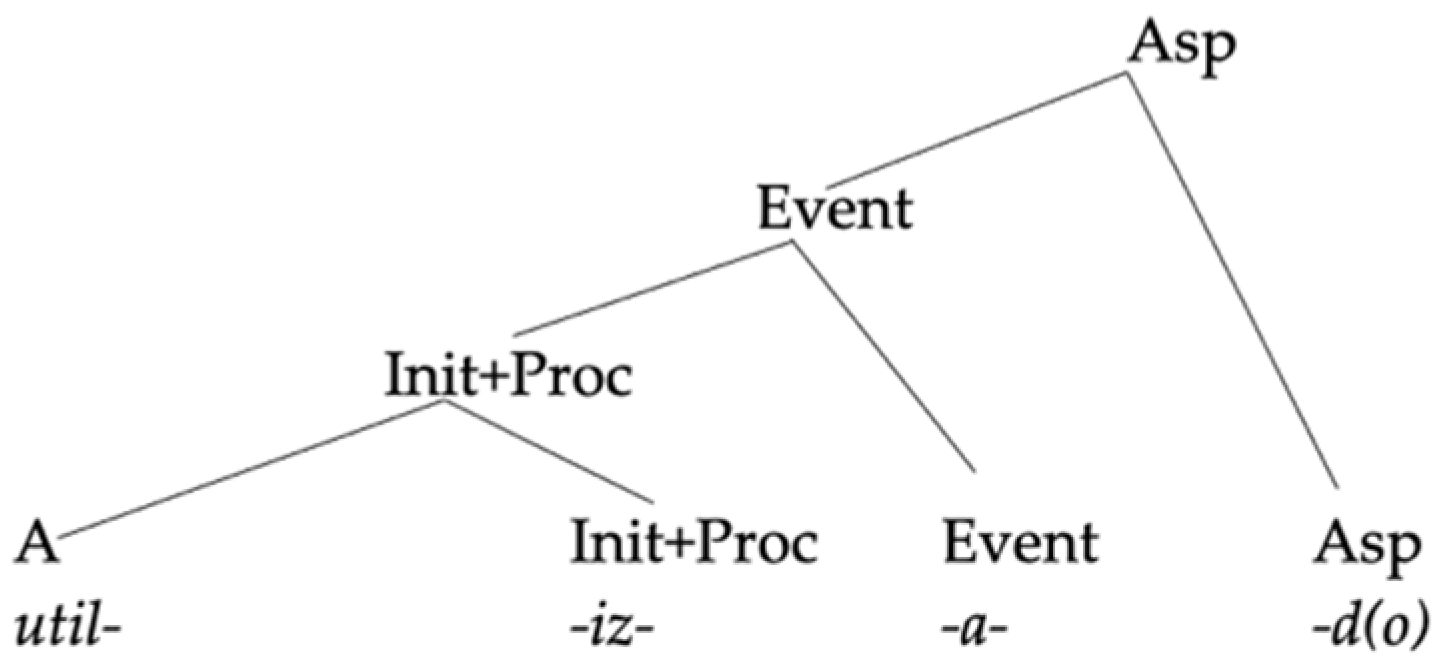

Given this, following the general reasoning, the absence of German roots verbalized by Spanish suffixes cannot be reduced to a competition between a German and a Spanish verbalizer, because the Spanish base is already verbalized. If there is any sense of default morphology at play here, that sense of default would rather be that, when the two structures overlap, the German exponent used is the one that spells out the minimal amount of structure that has not been already spelled out by the base, which in our analysis is Event, where otherwise Spanish would have introduced a theme vowel.