A Survey of Assessment and Additional Teaching Support in Irish Immersion Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How many students in Irish immersion education are in receipt of additional teaching support due to their special educational needs?

- What methods are used to select students for this additional teaching support?

- What are the challenges of appropriate assessment in Irish immersion education?

- What external support services2 are provided through the medium of Irish to students in these schools?

1.1. Literacy Assessment in Immersion Education

1.2. Alternative Measures of Assessment for Bilingual Students

1.3. Accessing Additional Teaching Support in the Republic of Ireland

1.4. Educational Professionals Assessing Students Learning through a Second Language

2. The Study

- How many students in Irish immersion education are in receipt of additional teaching support due to their special educational needs?

- What methods are used to select students for this additional teaching support?

- What are the challenges of appropriate assessment in Irish immersion education?

- What external support services are provided through the medium of Irish to students in these schools?

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.2. School Profiles

3. Results

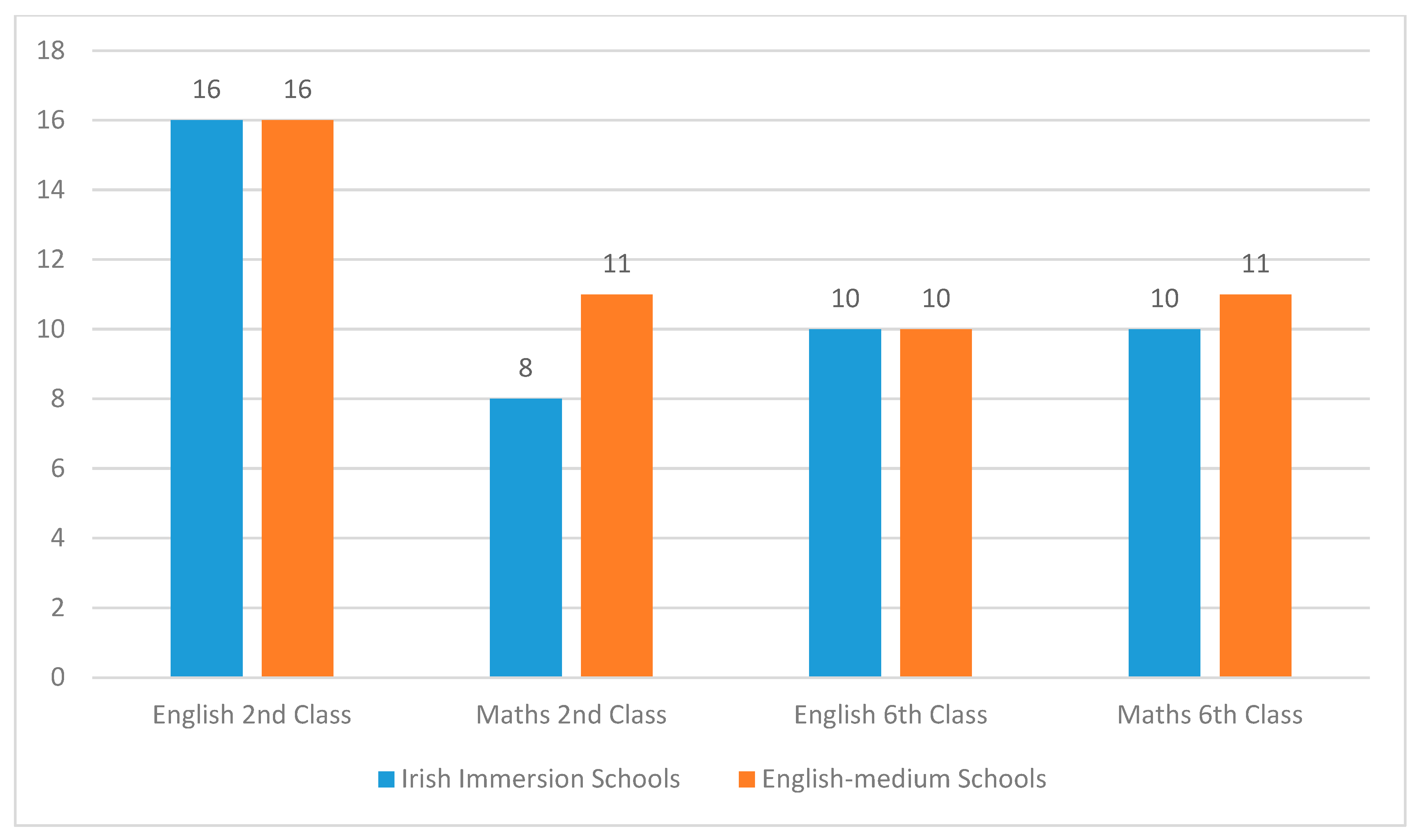

3.1. Students Receiving Additional Teaching Support

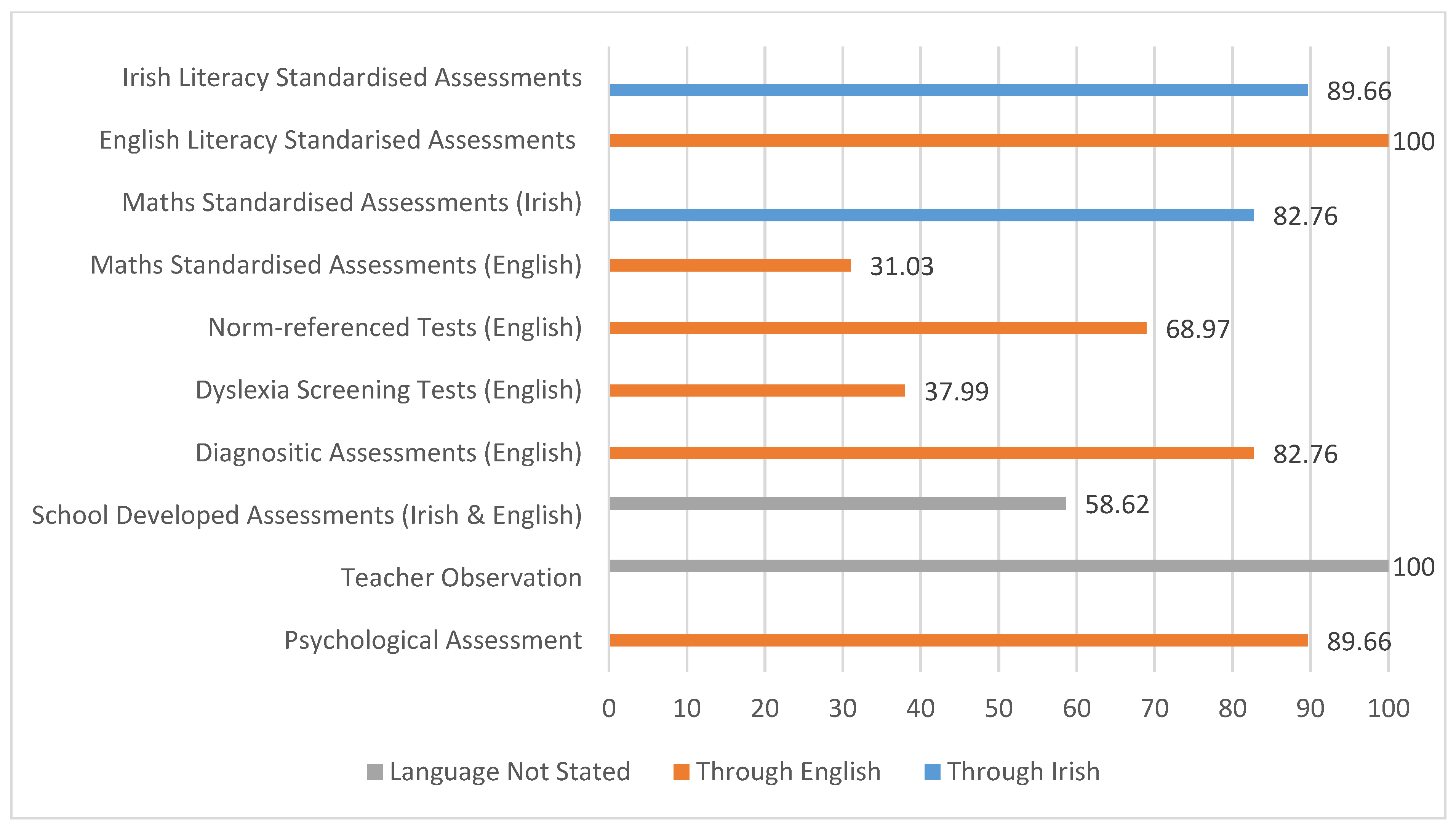

3.2. Assessment Methods for the Selection of Students for Additional Teaching Support

3.3. Standardised Tests Cut-Off Points for the Selection of Students for Additional Support

3.4. The Challenges of Assessing Students through the Medium of Irish

3.5. Access to External Services through the Medium of Irish

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availabilty Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| School Code |

| Principal | |

| Special Education Teacher | |

| Class Teacher | |

| Other… Please specify |

| No | |

| DEIS Band 1 | |

| DEIS Banda2 |

| Class Teachers | |

| Special Education Teachers (Full-time) | |

| Special Education Teachers (Part-time) | |

| Special Class Teachers | |

| Special Needs Assistants | |

| Other, Please Specify |

| Junior Infants | Senior Infants | First Class | Second Class | Third Class | Fourth Class | Fifth Class | Sixth Class | |

| Dyslexia | ||||||||

| Dyspraxia | ||||||||

| Physical Disability | ||||||||

| Hearing Impairment | ||||||||

| Visual Impairment | ||||||||

| Emotional Disturbance and/or Behavioural Problems | ||||||||

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder/Attention Deficit Disorder | ||||||||

| Severe Emotional Disturbance | ||||||||

| Mild General Learning Disability | ||||||||

| Moderate General Learning Disability | ||||||||

| Autism/Autistic Spectrum Disorder | ||||||||

| Specific Speech and Language Disorder | ||||||||

| Assessed syndrome | ||||||||

| Multiple Disabilities | ||||||||

| Other, Please Specify |

| Standardised Tests of Irish Literacy | |

| Standardised Tests of English Literacy | |

| Standardised Tests of Mathematics through the medium of Irish | |

| Standardised tests of mathematics through the medium of English | |

| Criterion referenced tests (m.sh., Middle Infant Screening Test) | |

| Dyslexia Screening Tests | |

| Diagnostic Tests (English medium) | |

| School Developed Assessments | |

| Teacher Observation | |

| Psychological Assessment | |

| Other, Please Specify |

| sTen Score | |

| Drumcondra test of Irish literacy | |

| Drumcondra test of English literacy | |

| Drumcondra Maths test through Irish | |

| Drumcondra Maths test through English | |

| Sigma- T (Maths through Irish) | |

| Sigma- T (Maths through English) | |

| Other, Please Specify |

| Drumcondra test of Irish literacy | |

| Drumcondra test of English literacy | |

| Drumcondra Maths test through Irish | |

| Drumcondra Maths test through English | |

| Sigma- T (Maths test through Irish) | |

| Sigma- T (Maths test through English) | |

| Micra T (English Literacy) | |

| Micra T (Irish Literacy) |

| Every Lesson | Everyday | Every Week | Every Month | Every Term | Every Year | |

| Co- teaching/Team teaching | ||||||

| In-class small group (4–6 students) work (co-operative learning) | ||||||

| Class withdrawal (groups 4–6 students) | ||||||

| Class withdrawal (pairs) | ||||||

| One-to-one tuition (withdrawal) | ||||||

| In-class heterogeneous grouping | ||||||

| In-class peer tutoring | ||||||

| Individualised programmes of learning | ||||||

| Student self-assessment | ||||||

| Students’ reflective journals | ||||||

| Reflective learning | ||||||

| Decision-making/Problem-based learning | ||||||

| Practical activities | ||||||

| Use Mind Maps©/Concept mapping | ||||||

| The Internet/ICT | ||||||

| Digital/still camera | ||||||

| DVD/Video/TV/Radio | ||||||

| Project work |

| Working through Irish | Working through English | Working through Irish and English | Service requested but unavailable | This service is not required | |

| Educational Psychologist | |||||

| Clinical Psychologist | |||||

| Speech and Language Therapist | |||||

| Occupational Therapist | |||||

| Physiotherapist | |||||

| Play Therapist | |||||

| Educational Welfare Officer | |||||

| Behavioural Support Services | |||||

| Medical Professional (e.g. nurse/doctor) | |||||

| Psychiatrist | |||||

| Counsellor | |||||

| Other, Please Specify |

| Very Challenging | Challenging | Somewhat Challenging | Never Challenging | |

| Class Size | ||||

| Inappropriate instruction | ||||

| Lack of in-class support | ||||

| Lack of support from home | ||||

| Use of inappropriate textbooks | ||||

| Insufficient differentiation | ||||

| Not enough time | ||||

| Unrealistic teacher expectations | ||||

| Lack of suitable resources | ||||

| Assessment tools through the medium of Irish | ||||

| Lack of support from external services through the medium of Irish | ||||

| School accommodation and facilities |

| Another Irish immersion school | |

| A special class in an Irish immersion school | |

| An English-medium mainstream school | |

| An English-medium special school | |

| A special class in an English-medium school |

| On the advice of the school principal/classroom teacher | |

| On the advice of an educational psychologist | |

| On the advice of a speech and language therapist | |

| On the advice of an occupational therapist | |

| The school was not able to support the student in their learning | |

| The student had a difficulty learning through Irish | |

| Parental concern | |

| Other, Please Specify |

| Yes | |

| No |

References

- Andrews, Sinéad. 2020. The Additional Supports Required by Pupils with Special Educational Needs in Irish-Medium Schools. An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/Additional-supports...-2.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Artiles, Alfredo J., Elizabeth B. Kozleski, Stanley C. Trent, David Osher, and Alba Ortiz. 2010. Justifying and explaining disproportionality, 1968–2008: A critique of underlying views of culture. Exceptional Children 76: 279–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Joanne, and Selina McCoy. 2011. A Study on the Prevalence of Special Educational Needs. Available online: https://www.esri.ie/system/files?file=media/file-uploads/2015-07/BKMNEXT198.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Barnes, Emily. 2017. Dyslexia Assessment and Reading Intervention for Pupils in Irish-Medium Education: Insights into Current Practice and Considerations for Improvement. Unpublished Master’s thesis. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/Trachtas-WEB-VERSION.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Barrett, Mary. 2016. Doras Feasa Fiafraí: Exploring Special Educational Needs Provision and Practices across Gaelscoileanna and Gaeltacht Primary Schools in the Republic of Ireland. Unpublished Master’s thesis. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/doras-feas-fiafrai.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Bedore, Lisa M., Elizabeth D. Pena, Ronald B. Gillam, and Tsung-Han Ho. 2010. Language sample measures and language ability in Spanish-English bilingual kindergarteners. Journal of Communication Disorders 43: 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerma, Tessel, and Elma Blom. 2017. Assessment of bilingual children: What if testing both languages is not possible? Journal of Communication Disorders 66: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bournot-Trites, Monique. 2008. Fostering reading acquisition in French immersion. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/9267582/Fostering_Reading_Acquisition_in_French_Immersion (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Caesar, Lena G., and Paula D. Kohler. 2007. The state of school-based bilingual assessment: Actual practice versus recommended guidelines. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 38: 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, Colin Terrence, and Denis Young. 2012. New Non-Reading Intelligence Tests 1-3 (NNRIT 1-3) Manual: Oral Verbal Group Tests of General Ability. Hodder Education. Available online: https://www.hoddereducation.co.uk/subjects/assessment/products/general/new-non-reading-intelligence-tests-1-3-manual (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Cleave, Patricia L., Luigi E. Girolametto, Xi Chen, and Carla J. Johnson. 2010. Narrative abilities in monolingual and dual language learning children with specific language impairment. Journal of Communication Disorders 43: 511–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta. 2010. Special Education Needs in Irish-Medium Schools. Dublin: An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/English8Feb.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Crutchley, Alison, Gina Conti-Ramsden, and Nicola Botting. 1997. Bilingual children with specific language impairment and standardized assessments: Preliminary findings from a study of children in language units. International Journal of Bilingualism 1: 117–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Jim. 2009. Bilingual and Immersion Programs. In The Handbook of Language Teaching. Edited by Michael H. Long and Catherine J. Doughty. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lamo White, Caroline, and Lixian Jin. 2011. Evaluation of speech and language assessment approaches with bilingual children. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 46: 613–27. [Google Scholar]

- de Valenzuela, Julia Scherba, Elizabeth Kay-Raining Bird, Karisa Parkington, Pat Mirenda, Kate Cain, Andrea AN MacLeod, and Eliane Segers. 2016. Access to opportunities for bilingualism for individuals with developmental disabilities: Key informant interviews. Journal of Communication Disorders 63: 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education (DE). 2011. Needs Assessment & Feasibility Study for the Development of High Level Diagnostic Tools in Irish for Children with Special Educational Needs in the Irish-Medium Sector. Available online: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk//14000/ (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). 2017a. Circular to the Management Authorities of all Mainstream Primary Schools Special Education Teaching Allocation. Available online: https://www.education.ie/en/Circulars-and-Forms/Active-Circulars/cl0013_2017.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). 2017b. DEIS Plan 2017 New DEIS Schools List. Available online: https://www.education.ie/en/Schools-Colleges/Services/DEIS-Delivering-Equality-of-Opportunity-in-Schools-/DEIS-Plan-2017-New-DEIS-Schools-List.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). 2020a. Learning Support Guidelines. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/ebd0d3-learning-support-guidelines/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). 2020b. Special Needs Education. Available online: https://www.education.ie/en/the-education-system/special-education/ (accessed on 23 February 2020).

- Ebert, Kerry Danahy, and Kathryn Kohnert. 2016. Language learning impairment in sequential bilingual children. Language Teaching 49: 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, Kerry Danahy, and Giang Pham. 2017. Synthesizing information from language samples and standardized tests in school-age bilingual assessment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 48: 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, Kerry Danahy, and Cheryl M. Scott. 2014. Relationships between narrative language samples and norm-referenced test scores in language assessments of school-age children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 45: 337–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Educational Research Centre. 2020a. ERC’s Tests for Schools. Available online: https://www.erc.ie/erc-paper-tests/ (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Educational Research Centre. 2020b. Drumcondra Irish Literacy Test. Available online: https://www.erc.ie/erc-paper-tests/overview/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Erdos, Caroline, Fred Genesee, Robert Savage, and Corinne A. Haigh. 2011. Individual differences in second language reading outcomes. International Journal of Bilingualism 15: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdos, Caroline, Fred Genesee, Robert Savage, and Corinne Haigh. 2014. Predicting risk for oral and written language learning difficulties in students educated in a second language. Applied Psycholinguistics 35: 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, Virginia C. Mueller. 2014. Bilingualism matters: One size does not fit all. International Journal of Behavioral Development 38: 359–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, Esther. 2006. Learning to Read in a Second Language: Research, Implications, and Recommendations for Services. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. Available online: https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/sites/default/files/textes-experts/en/614/learning-to-read-in-a-second-language-research-implications-and-recommendations-for-services.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- GL Assessment. 2020. Middle Infant Screening Test. Available online: https://www.gl-assessment.ie/products/middle-infant-screening-test-and-forward-together-mist/ (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Government of Ireland. 2004. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act 2004. Available online: http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2004/act/30/enacted/en/html (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Government of Ireland. 2020. DEIS Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/4018ea-deis-delivering-equality-of-opportunity-in-schools/#deis-plan-2017 (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Grimm, Angela, and Petra Schulz. 2014. Specific language impairment and early second language acquisition: The risk of over-and under diagnosis. Child Indicators Research 7: 821–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen, Vera F., Gabriela Simon-Cereijido, and Christine Wagner. 2008. Bilingual children with language impairment: A comparison with monolinguals and second language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics 29: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambly, Catherine, and Eric Fombonne. 2012. The impact of bilingual environments on language development in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42: 1342–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, Natalie, Bernard Camilleri, Caroline Jones, Jodie Smith, and Barbara Dodd. 2013. Discriminating disorder from difference using dynamic assessment with bilingual children. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 29: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, Erika, Cynthia Core, Silvia Place, Rosario Rumiche, Melissa Señor, and Marisol Parra. 2012. Dual language exposure and early bilingual development. Journal of Child Language 39: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 25.0. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jared, Debra, Pierre Cormier, Betty Ann Levy, and Lesly Wade-Woolley. 2011. Early predictors of biliteracy development in children in French immersion: A 4-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology 103: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnert, Kathryn. 2010. Bilingual children with primary language impairment: Issues, evidence and implications for clinical actions. Journal of Communication Disorders 43: 456–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, Joni M. 2012. Assessing the cognitive abilities of culturally and linguistically diverse students: Predictive validity of verbal, quantitative, and nonverbal tests. Psychology in the Schools 49: 756–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Constant, and Catriona Scott. 2009. Formative assessment in language education policies: Emerging lessons from Wales and Scotland. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 29: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCoubrey, Sharon, Lesly Wade-Woolley, Don Klinger, and John Kirby. 2004. Early identification of at-risk L2 readers. Canadian Modern Language Review 61: 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Deirdre. 2015. Dynamic assessment of language disabilities. Language Teaching 48: 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Sharynne, and Sarah Verdon. 2014. A review of 30 speech assessments in 19 languages other than English. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 23: 708–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2007. Language and Literacy in Irish-Medium Primary Schools: Supporting School Policy and Practice. Available online: www.ncca.ie/uploadedfiles/publications/LL_Supporting_school_policy.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 2019. Primary Language Curriculum. Available online: https://www.curriculumonline.ie/Primary/Curriculum-Areas/Primary-Language/ (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- National Council for Special Education (NCSE). 2015. Special Needs Assistant (SNA) Scheme Information for Parents/Guardians of Children and Young People with Special Educational Needs. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/NCSE-SNA-Scheme-Information-Pamphlet.FINALwebaccessibleversion.16.01.151.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- National Council for Special Education (NCSE). 2018. Annual Report 2018. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/NCSE-2018-Annual-Report.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- National Council for Special Education (NCSE). 2021. Visiting Teachers for Children and Young people who are Deaf/Hard of Hearing or Blind/Visually Impaired. Available online: https://ncse.ie/visiting-teachers (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Ní Chinnéide, Deirdre. 2009. The Special Educational Needs of Bilingual (Irish-English) Children, 52. POBAL, Education and Training. Available online: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/11010/7/de1_09_83755__special_needs_of_bilingual_children_research_report_final_version_Redacted.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2016).

- Nic Aindriú, S., P. Ó Duibhir, and J. Travers. 2020. The prevalence and types of special educational needs in Irish immersion primary schools in the Republic of Ireland. European Journal of Special Needs Education 35: 603–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Aindriú, Sinéad, Pádraig Ó Duibhir, and Joe Travers. 2020b. Students with special educational needs learning trough Irish/Daltaí a bhfuil riachtanais speisialta oideachais acu ag foghlaim trí Ghaeilge. ETBI Journal of Education. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/64995423/etbi-journal-of-education-vol-2-issue-2-november-2020 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- O’Toole, Ciara, and Tina M. Hickey. 2013. Diagnosing language impairment in bilinguals: Professional experience and perception. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 29: 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne. 2010. The interface between bilingual development and specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics 31: 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne, Fred Genesee, and Martha B. Crago. 2011. Dual Language Development & Disorder. Baltimore: Paul H, pp. 88–108. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Christine E., and Fiona Lyddy. 2009. Early reading strategies in Irish and English: Evidence from error types. Reading in a Foreign Language 21: 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pert, Sean, and Carolyn Letts. 2003. Developing an expressive language assessment for children in Rochdale with a Pakistani heritage background. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 19: 267–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesco, Diane, and Elizabeth Kay-Raining Bird. 2016. Perspectives on bilingual children’s narratives elicited with the Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives. Applied Psycholinguistics 37: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, Douglas B., and Ronald B. Gillam. 2013. Accurately predicting future reading difficulty for bilingual Latino children at risk for language impairment. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice 28: 113–28. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, Douglas B., Helen Chanthongthip, Teresa A. Ukrainetz, Trina D. Spencer, and Roger W. Steeve. 2017. Dynamic assessment of narratives: Efficient, accurate identification of language impairment in bilingual students. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 60: 983–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, Gary. J., and Gary S. Wilkinson. 2006. Wide Range Achievement Test, Fourth Edition (WRAT-4). Available online: https://www.pearsonclinical.co.uk/Psychology/ChildCognitionNeuropsychologyandLanguage/ChildAchievementMeasures/wrat4/wide-range-achievement-test-fourth-edition-wrat4.aspx (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Shiel, Gerry, Gilleece Lorraine, Clerkin Aidan, and Millar David. 2011. The 2010 National Assessments of English Reading and Mathematics in Irish-Medium Schools. Available online: https://www.erc.ie/documents/naims2010_summaryreport.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Simmons, Deborah C., Michael D. Coyne, Oi-man Kwok, Sarah McDonagh, Beth A. Harn, and Edward J. Kame’enui. 2008. Indexing response to intervention: A longitudinal study of reading risk from kindergarten through third grade. Journal of Learning Disabilities 41: 158–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stow, Carol, and Barbara Dodd. 2005. A survey of bilingual children referred for investigation of communication disorders: A comparison with monolingual children referred in one area in England. Journal of Multilingual Communication Disorders 3: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellutino, Frank R., Donna M. Scanlon, Haiyan Zhang, and Christopher Schatschneider. 2008. Using response to kindergarten and first grade intervention to identify children at-risk for long-term reading difficulties. Reading and Writing 21: 437–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, David. 2017. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test—Third UK Edition (WIAT-III UK). Available online: https://www.pearsonclinical.co.uk/Psychology/ChildCognitionNeuropsychologyandLanguage/ChildAchievementMeasures/wiat-iii/wechsler-individual-achievement-test-third-uk-edition-wiat-iii-uk.aspx (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Williams, Corinne J., and Sharynne McLeod. 2012. Speech-language pathologists’ assessment and intervention practices with multilingual children. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 14: 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, Nancy, and Xi Chen. 2010. At-risk readers in French immersion: Early identification and early intervention. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 13: 128–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, Nancy, and Xi Chen. 2015. Early intervention for struggling readers in grade one French immersion. The Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue Canadienne des Langues Vivantes 71: 288–306. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | DEIS: Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools, schools located in areas where children are at greatest risk of Educational disadvantage (Government of Ireland 2020). |

| 2 | These are services such as, educational psychologists, speech and language therapists, and occupational therapists which are provided outside of school. |

| 3 | Middle Infant Screening Test (MIST) is an early phonological assessment in English. |

| 4 | Drumcondra primary Irish literacy test is a standardised assessment that evaluates Irish listening and literacy skills. |

| 5 | English medium assessment of aspects language and thinking. |

| 6 | English medium assessment of reading, language and numerical attainment in one test. |

| 7 | English medium measure of the basic academic skills of reading, spelling and mathematics computation. |

| 8 | A special education teacher is a teacher who provides additional teaching support to students with learning difficulties (DES 2017a). |

| 9 | Some Irish immersion schools have a special class for students with SEN (DES 2020b for more info). |

| 10 | Special needs assistants assist the teacher in supporting students with SEN who have significant care needs (NCSE 2015). |

| 11 | A teaching Principal is a primary school teacher with both teaching duties and administrative duties in terms of managing the school on a day to day basis. |

| 12 | There are eight year groups in Irish primary schools (junior infants—6th class). Some schools have only one class per year group whilst others can have more than one, e.g. two junior infant classes etc. |

| 13 | Visiting teachers are qualified teachers with particular skills and knowledge of the development and education of children with varying degrees of hearing loss and/or visual impairment. They offer longitudinal support to children, their families and schools from the time of referral through to the end of post-primary education. (NCSE 2021). |

| School Type | Number of Irish Immersion Schools | Representative Sample (20%) |

|---|---|---|

| DEIS Schools | 15 | 3 |

| Schools with Special Classes | 4 | 1 |

| Urban (City) Schoolswith Teaching Principal11 (<203 students) | 7 | 1 |

| Urban (City) Schools with 1/2 classes per year group12 (203–410 students) | 21 | 4 |

| Urban (City) Schools with 2/3 classes per year group (>410 students) | 13 | 3 |

| Small Town SchoolsWith Teaching Principal(<203 students) | 30 | 6 |

| Small Town Schools with 1/2 classes per year group (203–410 students) | 44 | 9 |

| Small Town Schools with 2/3 classes per year group (>411 students) | 11 | 2 |

| Total | 145 | 29 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nic Aindriú, S.; Duibhir, P.Ó.; Travers, J. A Survey of Assessment and Additional Teaching Support in Irish Immersion Education. Languages 2021, 6, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020062

Nic Aindriú S, Duibhir PÓ, Travers J. A Survey of Assessment and Additional Teaching Support in Irish Immersion Education. Languages. 2021; 6(2):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020062

Chicago/Turabian StyleNic Aindriú, Sinéad, Pádraig Ó Duibhir, and Joe Travers. 2021. "A Survey of Assessment and Additional Teaching Support in Irish Immersion Education" Languages 6, no. 2: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020062

APA StyleNic Aindriú, S., Duibhir, P. Ó., & Travers, J. (2021). A Survey of Assessment and Additional Teaching Support in Irish Immersion Education. Languages, 6(2), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020062