The Effect of the Family Type and Home Literacy Environment on the Development of Literacy Skills by Bi-/Multilingual Children in Cyprus

Abstract

1. Introduction

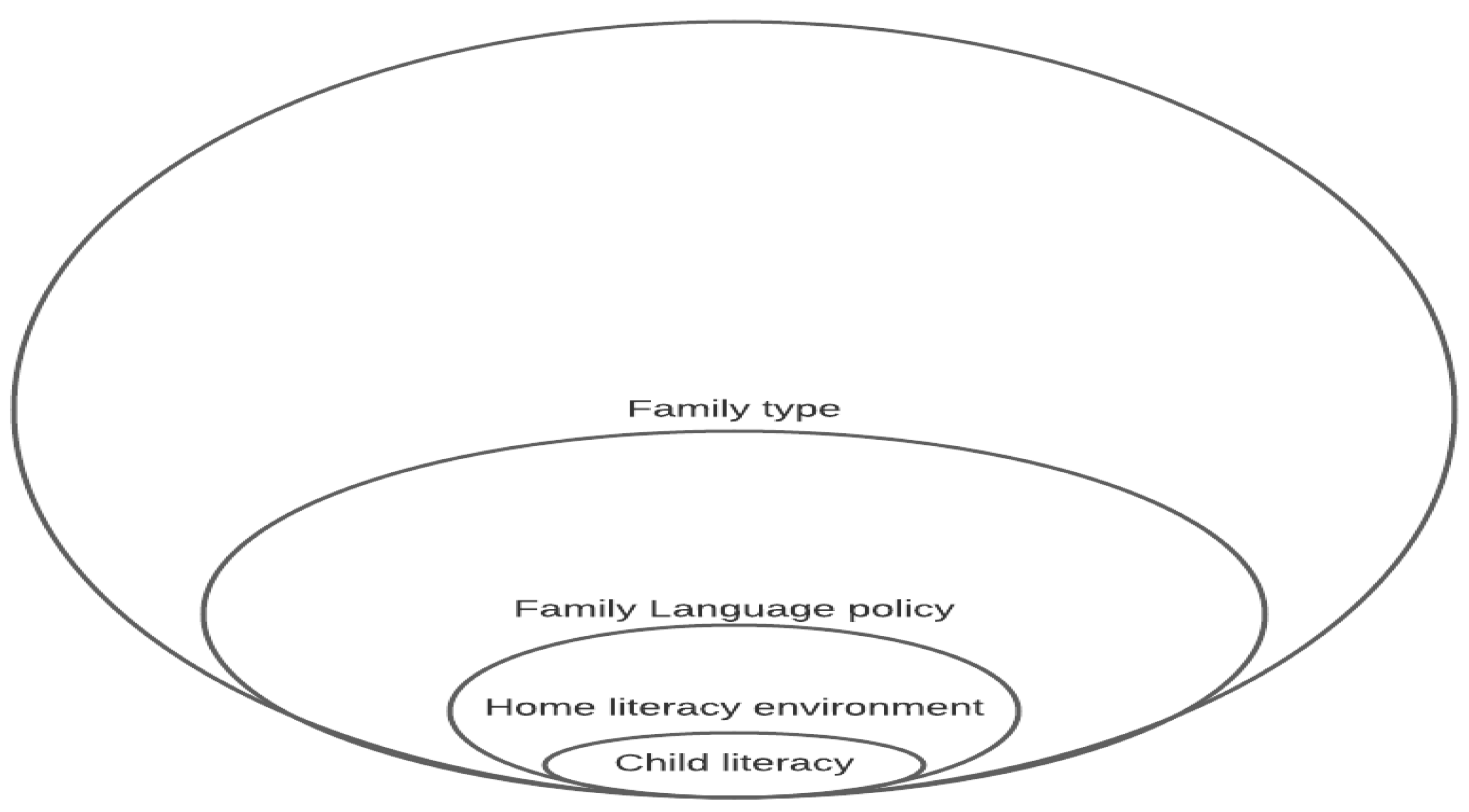

2. HLE and Child Literacy Development

2.1. Multilingualism and Multiliteracy

2.2. Home Literacy Activities in Bi-/Multilingual Families

2.3. Bi-/Multilingual Families in Cyprus: Endogamous vs. Exogamous

2.4. Rationale and Research Questions

- Which languages are used, and what types of home literacy practices are implemented in endogamous and exogamous immigrant Russian families in order to facilitate children’s literacy development?

- What are their motives and experiences regarding FLP, HLE and children’s literacy development?

- What are the factors that affect home language use, maintenance and transmission, and the development of language and literacy skills?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

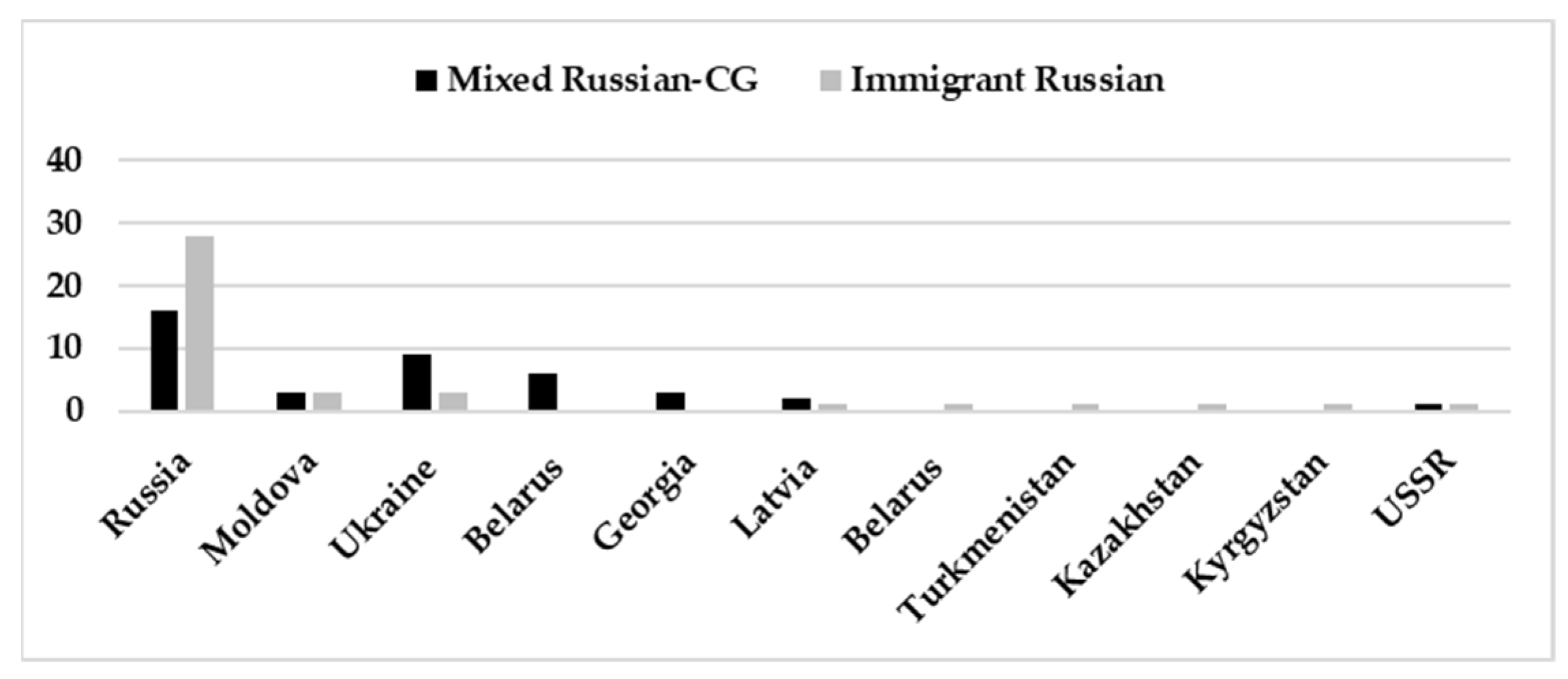

3.2. Participants

3.3. Materials and Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Family Type, Language Use, Schooling and Literacy Practices

4.1.1. FLP, HLE: Language Use and Literacy Skills

4.1.2. Parents’ Education Preferences for Their Children

- (1)

- This Russian kindergarten has a very pleasant, friendly atmosphere, it is like a small family. The teachers are professionals and they enjoy working with the children. They have an individual approach, which allows progress for every child. There are around 10 children in every group. It is important to see that your child is willing to go to the kindergarten every day. You cannot avoid [the] Russian mentality, for us it is important if they [teachers] take our needs into consideration. (Parent 16)

- (2)

- We cannot live without books, but after we have moved to Cyprus, we do not have so many printed books, mainly digital, it is more convenient and easier to buy online… for kids, we still try to order printed books as they need to touch them, to look at colorful pictures, to draw and write letters, sometimes I use a printer in order to print digital resources, it helps a lot… (Parent 50)

- (3)

- We have a Russian community in Cyprus and various social media platforms, so we communicate, share useful information and advice regarding education and entertainment, [and] exchange books, especially those needed at the Russian school… (Parent 78)

- (4)

- We like our English pre-primary school, there are a lot of educational opportunities, focus on sports and creativity; some children and their parents find it difficult due to the level of English… but it depends what you want for your child, what your aims are… we like the school. (Parent 2)

- (5)

- Our kids go to the English kindergarten; for such a young age, four years old, this kindergarten is ideal in terms of literacy skills, we have international teachers and a lot of creativity. They are kind and supportive and they do not give a lot of homework. My children are happy there, but of course children are different… (Parent 27)

4.1.3. FLP, HLE: Books, Educational Resources, and Literacy Activities

- (6)

- The Greek school is public, we do not pay for it, there is also an option of afternoon extra classes. The teachers can help the pupils to do their homework, which is very convenient for the parents who work and for us, as we do not know Greek, this is a way out, so my children are ready for school for the next day. They also have a snack and extra-curricular activities there, theater, computers, drawing, sports, and they can play together (Parent 33).

- (7)

- At home, we have different books, mainly Greek as my children go to the Greek pre-primary school, but we also have some Russian books, we bring them from Russia or we exchange them with our Russian friends in Cyprus, even some English books and magazines…yes, we are a multicultural family, we try to be…at home we speak Russian, but at work, only English, my husband and I do not know Greek, but my children speak Greek or English with their friends and teachers and only Russian with us… (Parent 45).

4.1.4. Integration into the Target Society: Majority vs. Home Language Use

- (8)

- My elder [child] speaks mainly Greek as he goes to the public Greek school, whereas my little one mixes two languages, as I try to teach him Russian but all the rest around him speak Greek and we will send him to the Greek kindergarten. I try as much as I can but I am not sure whether he will be able to read and write in Russian without attending extra lessons in Russian… (Parent 56)

- (9)

- My husband is Cypriot Greek and even though our daughter attends [a] Greek pre-primary school, her Greek is not good. I speak only Russian with her at home. I thought that if she is among Greek children, she would benefit a lot but her friends are foreigners and she speaks in English with them. (Parent 64)

- (10)

- I speak only in Russian with them from their birth, and my husband in Greek. My son does not have any problems, but my daughter knows English better, maybe because she constantly watches English cartoons. Her Greek is not so good, we send her to private lessons, her Russian is okay, but it could be better… (Parent 72)

- (11)

- Now Russian is everywhere, it is important to know it, they will be able to find a good job in the future, if they know Russian, but is not only spoken language, my children need to know how to read and write in Russian, at least at the basic level, who can help, of course teachers, private lessons, especially in our case as they go to Greek pre-primary, and it is quite expensive, but what can we do, I work, I do not have time, besides, I am not a specialist… (Parent 14)

- (12)

- I have bought different books, Russian, Greek and English, but my daughter will read and write only if I am next to her, otherwise not. I also switch on Russian, Greek and English channels so that she has exposure to these languages… we live in Cyprus and she needs to know the languages that are used here, I can help her only with Russian and a little bit with English, but not with Greek…My husband is busy at work but even when he has time, he is not willing to teach her how to read and write in Greek, but of course he speaks Greek with her… (Parent 29)

4.2. FLP, HLE: Types of Home Literacy Practices

- (13)

- My daughter is writing with spelling errors. I try to teach her, but the problem is that she writes mirror-image letters and numbers, I am worried. I have talked to her teacher at the pre-primary school, and she told us that she will overcome this problem with more practice and experience, thus, we do a lot of homework at home and practice a lot… (Parent 39)

- (14)

- Our child has his own tempo, rate, he does not always feel quite comfortable with reading and writing, probably he does not have enough tolerance to sit and write. Also, if he does not manage the same way as in Greek then he loses interest…I know we need to support him, be with him, praise him, show him how to write in the correct way, but it requires a lot of time and we do not have it every day, only at the weekend, unfortunately… (Parent 41)

- (15)

- I think that I am too stressed and pressed with my work so that my child can feel it. I do not know what we would do if we did not have my parents with us. We are lucky as they are staying now with us. They just have so much patience and so much time, they can just hug my children, sit with them, talk to them, laugh together, they can show them how to write in a correct way, they can read together fairy tales or an ABC book, and my kids are just thrilled…so time is the magic! (Parent 51)

- (16)

- We like these ABC books with big letters. Our daughter likes to color them, she can imitate how to write, she just follows the line. I teach her how to pronounce each letter, she repeats. I think that we are doing really well, and of course the kindergarten helps a lot… (Parent 67)

- (17)

- My daughter goes to the English pre-primary, they learn English letters there, how to write and read, and then it is difficult for them to do it in Russian, they mix and substitute letters and I think that even their accent has changed, as they spend nearly all day there and they use only English with their teacher and peers… (Parent 73)

- (18)

- What we do is that we try to play, to have fun together, we have the sticky notes around the house, we write different letters in two languages or pictures with different objects, so the children can name the letters, the objects in their two languages, they can draw or color…we also like to sing songs together or read or look through colorful child books…and of course cartoons… my kids just cannot live without them, English, Russian and Greek, any language… (Parent 5)

- (19)

- We practice reading aloud around 20 min a day, our daughter likes it, we do it in the evening. It is the same child book with short poems. First, we have learned all the poems by heart and now she reads them… this is so exciting to see how your child reads, especially in Russian… as now we live in Cyprus and all people around speak Greek… (Parent 19)

- (20)

- We always praise our children, pressure is not good, it is important to emphasize their progress, to show how happy you are with what they are doing, otherwise they lose their interest, they feel when we [parents] are interested, when we listen to them, they want to show off and continue, they need to know that we highly value what they are doing… for me my children are my entire world… I am lucky I do not work so I can devote my time to my children… (Parent 23)

- (21)

- The most crucial is the child’s interest, if they find a book interesting, then they will do it, I mean we can read it together, so it should have colorful pictures or the story should be interesting otherwise they get bored very easily… you need to get them involved… you know we have two boys, they are hyperactive, it is difficult for them to sit in one place, so we change the activities… (Parent 47)

- (22)

- Our teacher at the pre-primary school gave us the advice to copy, imitate and rewrite letters, for example, to write a letter ‘’a’’ 10 times until it is perfect, my daughter likes it, while my son feels bored… (Parent 80)

- (23)

- Well, I think that my son is influenced by the Greek language, he has a Greek accent when he speaks in Russian, when he reads in Russian, he is not sure about the word stress, as for writing, he can mix letters, for example, use English or Greek letters, he is still in the pre-primary, the Greek one, we have also sent him to the Russian Saturday school so we hope that this will help… (Parent 53)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Adserà, Alícia, and Ana Ferrer. 2014. Immigrants and demography: Marriage, divorce, and fertility. In Handbook on the Economics of International Migration. Edited by Barry Chiswick and Paul Miller. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 315–74. [Google Scholar]

- Aikens, Nikki, and Oscar Barbarin. 2008. Socioeconomic differences in reading trajectories: The contribution of family, neighbourhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology 100: 235–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amantay, Assem. 2017. Kazakh Family Engagement in Early Language and Literacy Learning: A Case Study in Urban Kazakhstan. Master’s thesis, Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education, Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, Gunnar, Ognjen Obućina, and Kirk Scott. 2015. Marriage and Divorce of Immigrants and Descendants of Immigrants in Sweden. Demographic Research 33: 31–64. Available online: https://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol33/2/ (accessed on 25 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Aram, Dorit, Ofra Korat, and Safieh Hassunah-Arafat. 2013. The contribution of early home literacy activities to first grade reading and writing achievements in Arabic. Reading and Writing 26: 1517–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, Arlene, and Esther Breuer. 2015. Methodological and pedagogical approaches to multimodality in writing. In Multimodality in Writing. The State of the Art in Theory, Methodology and Pedagogy. Edited by Arlene Archer and Esther Odilia Breuer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa, and David Singleton. 2008. Multilingualism as a new linguistic dispensation. International Journal of Multilingualism 5: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Paul. 2015. For Ethnography. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, David, and Mary Hamilton. 1998. Local literacies: Reading and Writing in One Community. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Behtoui, Alireza. 2010. Marriage pattern of immigrants in Sweden. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 41: 415–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjatia, Tej K., and William C. Ritchie. 2012. The Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism. Malden, Oxford and Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Boccagni, Paolo, and Mieke Schrooten. 2018. Participant observation in migration studies: An overview and some emerging issues. In Qualitative Research in European Migration Studies. Edited by Ricard Zapata-Barrero and Evren Yalaz. IMISCOE Research Series; New York and London: IMISCOE, pp. 209–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bohman, Thomas, Lisa Bedore, Elizabeth Peña, Anita Mendez-Perez, and Ronald Gillam. 2010. What you hear and what you say: Language performance in Spanish–English bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 13: 325–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, Colleen. 2020. Hybrid identity and practices to negotiate belonging: Madrid’s Muslim youth of migrant origin. Comparative Migration Studies 8: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratich, Jack. 2018. Observation in a surveilled world. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thosand Oakes: Sage Publications, pp. 526–45. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, Esther O., Eva Lindgren, Anat Stavans, and Elke van Steendam. 2021. Multilingual Literacy. New Perspectives on Language and Education 85. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- British Psychological Society. 2014. Code of Human Research Ethics. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/bps-code-human-research-ethics-2nd-edition-2014 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Brown, James Dean. 2001. Using Surveys on Language Programs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Antony, and Kathy Charmaz. 2019. The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, Stephen, Steven Hecht, and Christopher Lonigan. 2002. Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: A one-year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly 37: 408–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, Sarah. 2013. English in Cyprus or Cyprus English? An Empirical Investigation of Variety Status. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Carol, Sarah. 2013. Intermarriage attitudes among minority and majority groups in Western Europe: The role of attachment to the religious in-group. International Migration 51: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Crystal. 2013. The Effects of Parental Literacy Involvement and Child Reading Interest on the Development of Emergent Literacy Skills. Ph.D. dissertation, UW-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA. Available online: http://dc.uwm.edu/etd/230/ (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Catalano, Theresa. 2016. Talking about Global Migration: Implications for Language Teaching. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2013. Defining multilingualism. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xiao, Zhou Hui Zhao, and Gareth Davey. 2010. Home literacy experiences and literacy acquisition among children in Guangzhou, South China. Psychological Reports 107: 354–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimienti, Milena, Alice Bloch, Laurence Ossipow, and Catherine Wihtol de Wenden. 2019. Second generation from refugee backgrounds in Europe. Comparative Migration Studies 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielska, Malgorzata, Katarzyna W. Boström, and Magnus Öhlander. 2018. Observation methods. In Qualitative Methodologies in Organisations Studies. Edited by Malgorzata Ciesielska and Dariusz Jamielniak. London: Palgrave McMillian, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Maion, and Keith Morrison. 2011. Research Methods in Education. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, and Keith Morrison. 2003. Research Methods in Education. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Vivian J. 1992. Evidence for multi-competence. Language Learning 42: 557–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, Bill, and Mary Kalantzis. 2000. Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, Bill, and Mary Kalantzis. 2009. Multiliteracies: New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal 4: 164–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, Bill, and Mary Kalantzis. 2015. The things you do to know: An introduction to the pedagogy of multiliteracies. In A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Learning by Design. Edited by Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis. London: Palgrave, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Beverley, and Stephen Briggs. 2014. Service-users’ experiences of interpreters in psychological therapy: A pilot study. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 10: 231–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 2004. Multiliteracies pedagogy and the role of identity texts. In Teaching for Deep Understanding: Towards the Ontario Curriculum That We Need. Edited by Kenneth Leithwood, Pat McAdie, Nina Bascia and Anne Rodrigue. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto and the Elementary Federation of Teachers of Ontario, pp. 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 2009. Pedagogies of choice: Challenging coercive relations of power in classrooms and communities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 12: 261–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Jim. 2015. How to reverse a legacy of exclusion? Identifying high-impact educational responses. Language and Education 29: 272–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan, and Jing Huang. 2020. Factors influencing family language policy. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development. Edited by Andrea C. Schalley and Susaba A. Eisenchlas. Berlin and Boston: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 174–94. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2009. Invisible and visible language planning: Ideological factors in the family language policy of Chinese immigrant families in Quebec. Language Policy 8: 351–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2013. Family language policy: Sociopolitical reality versus linguistic continuity. Language Policy 12: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2018. Family language policy. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Policy and Planning. Edited by James W. Tollefson and Miguel Perez-Milans. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 420–41. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2020. Observations and field notes: Recording lived experiences. In The Routledge Handbook of Researh Methods in Applied Linguistics. Edited by Jim McKinley and Heath Rose. London: Routledge, pp. 336–48. [Google Scholar]

- De Costa, Peter I., Jongbong Lee, Hima Rawal, and Wendy Li. 2020. Ethics in applied linguistics research. In The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Edited by Jim McKinley and Heath Rose. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 122–31. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, Annick. 2007. Parental language input patterns and children’s bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics 28: 411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2013. Emotions in Multiple Languages. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2018. Why the dichotomy ‘L1 versus LX User’ is better than ‘Native versus Non-native Speaker’. Applied Linguistics 39: 236–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L. Quentin. 2011. The role of home and school factors in predicting English vocabulary among bilingual kindergarten children in Singapore. Applied Psycholinguistics 32: 141–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán, and Tatsuya Taguchi. 2010. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration and Processing. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dribe, Martin, and Christer Lundh. 2008. Intermarriage and immigrant integration in Sweden: An exploratory analysis. Acta Sociologica 51: 329–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dribe, Martin, and Christer Lundh. 2011. Cultural dissimilarity and intermarriage: A longitudinal study of immigrants in Sweden 1990–2005. International Migration Review 45: 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eracleous, Natalia. 2015. Linguistic Landscape of Limassol: Russian Presence. Master’s thesis, University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Ergül, Cevriye, Ayşe Dolunay Sarica, Gözde Akoglu, and Gökçe Karaman. 2017. The home literacy environments of Turkish kindergarteners: Does SES make a difference? International Journal of Instruction 10: 187–202. Available online: http://www.e-iji.net/dosyalar/iji_2017_1_12.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Feng, Zhiqiang, Paul Boyle, Maarten van Ham, and Gillian M. Raab. 2012. Are mixed-ethnic unions more likely to dissolve than co-ethnic unions? New evidence from Britain. European Journal of Population 28: 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Flower, Linda. 1989. Cognition, context, and theory building. College Composition and Communication 40: 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, Geraldine, Virpi Timonen, Catherine Conlon, and Catherine Elliott O’Dare. 2021. Interviewing as a vehicle for theoretical sampling in grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, Martha, Richard Lambert, Martha Abbott-Shim, Frances McCarty, and Sarah Franze. 2005. A model of home learning environment and social risk factors in relation to children’s emergent literacy and social outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 20: 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, Delia. 2012. Human capital and interethnic marriage decisions. Economic Inquiry 50: 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Ofelia, Lesley Bartlett, and JoAnne Kleifgen. 2007. From biliteracy to pluriliteracies. In Handbook of Multilingualism and Multilingual Communication. Edited by Peter Auer and Li Wei. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 207–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole, Virginia, and Enlli Môn Thomas. 2009. Bilingual first-language development: Dominant language takeover, threatened minority language take-up. Bilingualism 12: 213–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, James. 1992. The Social Mind: Language, Ideology, and Social Practice. London: JF Bergin & Garvey. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, James. 2015. The new Literacies Studies. In The Routledge Handbook of Literacy Studies. Edited by Jennifer Rowsell and Kate Pahl. London: Routledge, pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadou, Lorena. 2016. ‘’You look like them’’: Drawing on counselling theory and practice to reflexively negotiate cultural difference in research relationships. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 38: 358–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Barbara, and Hua Zhu. 2016. Interviews. In Research Methods in Intercultural Communication: A Practical Guide. Edited by Hua Zhu. Oxford: Wiley, pp. 181–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gillham, Bill. 2007. Developing a Questionnaire. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Judith, and Nicki Thorogood. 2014. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 3rd ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Eve, and Ann Williams. 2000. Work or play? Unofficial literacies in the lives of two East London communities. Multilingual Literacies 10: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, Eve. 1996. Making Sense of a New World: Learning to Read in a Second Language. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Eve. 2001. Sisters and brothers as language and literacy teachers: Synergy between siblings playing and working together. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 1: 301–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, Kleanthes K., Elena Papadopoulou, and Charalambos Themistocleous. 2017. Acquiring clitic placement in bilectal settings: Interactions between social factors. Frontiers in Communication 2: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullickson, Aaron. 2006. Education and black-white interracial marriage. Demography 43: 673–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjioannou, Xenia, Stavroula Tsiplakou, and Matthias Kappler. 2011. Language policy and language planning. Current Issues in Language Planning 12: 503–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, Martyn, and Paul Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hannemann, Tina, Hill Kulu, Leen Rahnu, Allan Puur, Mihaela Hărăguș, Ognjen Obućina, Amparo González Ferrer, Karel Neels, Layla Van den Berg, Ariane Pailhé, and et al. 2018. Co-ethnic marriage versus intermarriage among immigrants and their descendants: A comparison across seven European countries using event-history analysis. Demographic Research 39: 478–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay-Gibson, Naomi. 2009. Interviews via VoIP: Benefits and disadvantages within a PhD study of SMEs. Library and Information Research 33: 1756–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, Monica, and Alexandre Duchêne. 2012. Pride and profit: Changing discourses of language, capital and nation-state. In Language in Late Capitalism: Pride and Profit. Edited by Alexandre Duchêne and Monica Heller. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Monica, and Mireille McLaughlin. 2017. Language choice and symbolic domination. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Volume Language Choice and Symbolic Domination. Edited by Stephen May. Berlin: Springer, pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Herdina, Philip, and Ulrike Jessner. 2002. A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism: Perspectives of Change in Psycholinguistics. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Donald, Nancy Denton, and Suzanne Macartney. 2007. Demographic trends and the transition years. In School Readiness and the Transition to Kindergarten in the Era of Accountability. Edited by Robert Pianta, Martha Cox and Kyle Snow. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, pp. 217–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, Erika, Cynthia Core, Silvia Place, Rosario Rumiche, Melissa Señor, and Marisol Parra. 2012. Dual language exposure and early bilingual development. Journal of Child Language 39: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoff, Erika. 2013. Interpreting the early language trajectories of children from low-SES and language minority homes: Implications for closing achievement gaps. Developmental Psychology 49: 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Prue, Richard Fay, Jane Andrews, and Mariam Attia. 2013. Researching multilinguality: New theoretical and methodological directions. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 23: 285–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Michelle, Elizabeth Conlon, and Glenda Andrews. 2008. Preschool home literacy practices and children’s literacy development: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology 100: 252–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaniec, Janina. 2020. Questionnaires: Implications for effective implementation. In The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Edited by Jim McKinley and Heath Rose. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 324–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, Danny. 2015. Participant observation. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioural Sciences. Edited by Robert A. Scott and Stephen Michael Kosslyn. Oxford: Wiley Publications, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantzis, Mary, and Bill Cope. 2015. Regime of literacy. In Negotiating Spaces for Literacy Learning: Multimodality and Governmentality. Edited by Mary Hamilton, Rachel Heydon, Kathryn Hibbert and Roz Stooke. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn, Matthijs, and Frank Van Tubergen. 2006. Ethnic intermarriage in the Netherlands: Confirmations and refutations of accepted insights. European Journal of Population 22: 371–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, Jannicke, Solveig-Alma Halaas Lyster, and Arne Lervåg. 2017. Vocabulary development in Norwegian L1 and L2 learners in the kindergarten–school transition. Journal of Child Language 44: 402–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpava, Sviatlana, Natasha Ringblom, and Anastassia Zabrodskaja. 2019. Translanguaging in the family context: Evidence from Cyprus, Sweden and Estonia. Russian Journal of Linguistics 23: 619–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpava, Sviatlana, Ringblom Natasha, and Zabrodskaja Anastassia. 2018. Language ecology in Cyprus, Sweden and Estonia: Bilingual Russian-speaking families in multicultural settings. Journal of the European Second Language Association 2: 107–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpava, Sviatlana. 2015. Vulnerable Domains for Cross-linguistic Influence in L2 Acquisition of Greek. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Karpava, Sviatlana. 2020. Dominant language constellations of Russian speakers in Cyprus. In Dominant Language Constellations, Educational Linguistics. Edited by Joseph Lo Bianco and Larissa Aronin. Basel: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Clare. 2010. Hidden Worlds. Young Children Learning Literacy in Multicultural Contexts. Stoke on Trent: Trentham. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Charlotte. 2009. Defining multilingualism. In The Exploration of Multilingualism: Development of Research on L3, Multilingualism, and Multiple Language Acquisition. Edited by Larissa Aronin and Britta Hufeisen. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kenner, Charmian, and Ruby Mahera. 2012. Connecting children’s worlds: Creating a multilingual syncretic curriculum through partnership between complementary and mainstream schools. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 13: 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenner, Charmian, Gunther Kress, Hayat Al-Khatib, Roy Kam, and Kuan-Chun Tsai. 2004. Finding the keys to biliteracy: How young children interpret different writing systems. Language and Education 18: 124–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Kendall, Lyn Fogle, and Aubrey Logan-Terry. 2008. Family language policy. Language and Linguistics Compass 2: 907–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, Claudine. 2021. Promoting multilingualism and multiliteracies through storytelling: A case study on the use of the app iTEO in preschools in Luxembourg. In Multilingual Literacy. Edited by Esther Odilia Breuer, Eva Lindgren, Anat Stavans and Elke van Steendam. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 260–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, Melvin, and Carmi Schooler. 1983. Work and Personality: An Inquiry into the Impact of Social Stratification. Norwood: Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Krijnen, Eke, Roel van Steensel, Marieke Meeuwisse, Joran Jongerling, and Sabine Severiens. 2020. Exploring a refined model of home literacy activities and associations with children’s emergent literacy skills. Reading and Writing 33: 207–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulu, Hill, and Amparo González-Ferrer. 2014. Family dynamics among immigrants and their descendants in Europe: Current research and opportunities. European Journal of Population 30: 411–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulu, Hill, and Tina Hannemann. 2016. Why Does Fertility Remain High among Certain UK-Born Ethnic Minority Women? Demographic Research 35: 1441–88. Available online: https://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol35/49/default.htm (accessed on 10 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Kulu, Hill, Tina Hannemann, Ariane Pailhé, Karel Neels, Sandra Krapf, Amparo González-Ferrer, and Gunnar Andersson. 2017. Fertility by birth order among the descendants of immigrants in selected European countries. Population and Development Review 43: 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, Steinar. 2007. Qualitative Research Kit: Doing Interviews. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, Elizabeth, and Rafael Lomeu Gomes. 2020. Family language policy: Foundations, theoretical perspectives and critical approaches. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development. Edited by Andrea C. Schalley and Susana A. Eisenchlas. Berlin and Boston: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 153–44. [Google Scholar]

- Leseman, Paul, and Peter F. de Jong. 1998. Home Literacy: Opportunity, Instruction, Cooperation and Social-Emotional Quality Predicting Early Reading Achievement. Reading Research Quarterly 33: 294–318. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/748307 (accessed on 1 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Leszczensky, Lars, Rahsaan Maxwell, and Erik Bleich. 2019. What factors best explain national identification among Muslim adolescents? Evidence from four European countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46: 260–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddicoat, Anthony J. 2007. An Introduction to Conversational Analysis. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Lizardo, Omar. 2017. Improving cultural analysis: Considering personal culture in its declarative and nondeclarative modes. American Sociological Review 82: 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohndorf, Regina, Harriet Vermeer, Rodrigo Carcamo, and Judi Mesman. 2018. Preschoolers’ vocabulary acquisition in Chile: The roles of socioeconomic status and quality of home environment. Journal of Child Language 45: 559–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonigan, Christopher, David Purpura, Shauna Wilson, Patricia Walker, and Jeanine Clancy-Menchetti. 2013. Evaluating the components of an emergent literacy intervention for preschool children at risk for reading difficulties. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 114: 111–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, Jacqueline, Jim Anderson, Ann Anderson, and Jon Shapiro. 2006. Parents’ beliefs about young children’s literacy development and parents’ literacy behaviors. Reading Psychology 27: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, Charles M., Steve Graham, and Jill Fitzgerald. 2016. Handbook of Writing Research. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Steve. 2011. A critical review of qualitative interviews. Applied Linguistics 32: 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolitsis, George, George Georgiou, and Niki Tziraki. 2013. Examining the effects of home literacy and numeracy environment on early reading and math acquisition. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 28: 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolitsis, George, George Georgiou, and Rauno Parrila. 2011. Revisiting the home literacy model of reading development in an orthographically consistent language. Learning and Instruction 21: 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, Viorica, and Anthony Shook. 2012. The Cognitive Benefits of Being Bilingual. Cerebrum: Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, Jackie, Peter Hannon, Margaret Lewis, and Louise Ritchie. 2017. Young children’s initiation into family literacy practices in the digital age. Journal of Early Childhood Research 15: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alvarez, Patricia, and María Paula Ghiso. 2014. Multilingual, multimodal compositions in technology-mediated hybrid spaces. In Digital Tools for Writing Instruction in K-12 Settings: Student Perception and Experience. Edited by Rebecca S. Anderson and Clif Mims. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Jones, Marilyn. 2000. Bilingual classroom interaction: A review of recent research. Language Teaching 33: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTavish, Marianne. 2009. I get my facts from the internet: A case study of the teaching and learning of information literacy in in-school and out-of-school contexts. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 9: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Xin, and Robert G. Gregory. 2005. Intermarriage and the economic assimilation of immigrants. Journal of Labour Economics 23: 135–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, Robert K. 1941. Intermarriage and the social structure: Fact and theory. Psychiatry 4: 371–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewski, Nadja, and Hill Kulu. 2014. Mixed marriages in Germany: A high risk of divorce for immigrant-native couples. European Journal of Population 30: 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, Luis C., Cathy Amanti, Deborah Neff, and Norma González. 1992. Funds of knowledge for teaching. Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Practice 31: 132–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, Rahat, Anne McKeough, Keoma Thorne, and Christina Pfitscher. 2012. Dual-language books as an emergent-literacy resource: Culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and learning. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 13: 501–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New London Group. 1996. A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review 66: 60–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, Frank, and Wolfgang Schneider. 2013. Home literacy environment and the beginning of reading and spelling. Contemporary Educational Psychology 38: 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Henrietta, Clare Madge, Robert Shaw, and Jane Wellens. 2008. Internet-based interviewing. In The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods. Edited by Nigel Fielding, Raymond M. Lee and Grant Blank. London: Sage, pp. 271–89. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, Michelle, and Nikki Kiyimba. 2015. Advanced Qualitative Research: A Guide to Using Theory. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García, and Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6: 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otwinowska, Agnieszka, and Sviatlana Karpava. 2015. MILD Questionnaire: Migration, Identity and Language Discrimination/Diversity. Pyla: University of Central Lancashire, Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, Panayiotis. 2014. Exceptional clitic placement in Cypriot Greek: Results from an MET study. Journal of Greek Linguistics 14: 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2015. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Los Angeles, London and New Dehli: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Izaguirre, Elizabeth, and Jasone Cenoz. 2020. Immigrant students’ minority language learning: An analysis of language ideologies. Ethnography and Education 16: 145–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Kristen. 2012. What is Literacy?—A Critical Overview of Sociocultural Perspectives. Journal of Language and Literacy Education 8: 50–71. Available online: http://jolle.coe.uga.edu (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Phipps, Alison. 2013. Intercultural ethics: Questions of methods in language and intercultural communication. Language and Intercultural Communication 13: 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, Silvia, and Erika Hoff. 2016. Effects and non-effects of input in bilingual environments on dual language skills in 2 ½-year-olds. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 1023–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro, Rosa Aparicio, and William Haller. 2016. Spanish Legacies: The Coming of Age of the Second Generation. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prevoo, Mariëlle, Maike Malda, Judi Mesman, Rosanneke Emmen, Nihal Yeniad, Marinus van Ijzendoorn, and Mariëlle Linting. 2014. Predicting ethnic minority children’s vocabulary from socioeconomic status, maternal language and home reading input: Different pathways for host and ethnic language. Journal of Child Language 41: 963–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, Matthew T. 2016. Emotion and Discourse in L2 Narrative Research. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, Matthew T. 2017. Accomplishing ‘’rapport’’ in qualitative research interviews: Empathic moments in interaction. Applied Linguistics Review 9: 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell-Gates, Victoria. 2007. Cultural Practices of Literacy: Case Studies of Language, Literacy, Social Practice and Power. Mahwah: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Zhenchao, and Daniel T. Lichter. 2007. Social boundaries and marital assimilation: Interpreting trends in racial and ethnic intermarriage. American Sociological Review 72: 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, Blanca, Catherine Snow, and Jing Zhao. 2010. Vocabulary skills of Spanish—English bilinguals: Impact of mother—child language interactions and home language and literacy support. International Journal of Bilingualism 14: 379–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, Leslie, Rebeca Mejía Arauz, and Antonio Ray Bazán. 2012. Mexican parents’ and teachers’ literacy perspectives and practices: Construction of cultural capital. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 25: 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, Pia. 2018. Multilinguals’ Verbalisation and Perception of Emotions. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Joanne, Julia Jurgens, and Margaret Burchinal. 2005. The role of home literacy practices in preschool children’s language and emergent literacy skills. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 48: 345–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez García, Dan. 2006. Mixed marriages and transnational families in the intercultural context: A case study of African/Spanish couples in Catalonia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 32: 403–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, Louise, Jean-Marc Dewaele, and Beverley Costa. 2020. Planning and conducting interviews: Power, language. In The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Edited by Jim McKinley and Heath Rose. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 279–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, Michael J. 2010. Still weak support for status exchange theory. American Journal of Sociology 115: 1264–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydland, Veslemøy, and Vibeke Grøver. 2020. Language use, home literacy environment, and demography: Predicting vocabulary skills among diverse young dual language learners in Norway. Journal of Child Language, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydland, Veslemøy, Vibeke Grøver, and Joshua Lawrence. 2014. The second-language vocabulary trajectories of Turkish immigrant children in Norway from ages five to ten: The role of preschool talk exposure, maternal education, and co-ethnic concentration in the neighborhood. Journal of Child Language 41: 352–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, Mirma. 2010. Patterns of Immigrant Intermarriage in France: Intergenerational Marital Assimilation? Zeitschrift für Familienforschung 22: 89–108. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-354881 (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Scheele, Anna, Paul Leseman, and Aziza Mayo. 2010. The home language environment of monolingual and bilingual children and their language proficiency. Applied Psycholinguistics 31: 117–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Mila, and Anna Verschik. 2013. Successful Family Language Policy: Parents, Children and Educators in Interaction. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Mila. 2020. Strategies and practices of home language maintenance. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development. Edited by Andrea C. Schalley and Susana A. Eisenchlas. Berlin and Boston: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 194–218. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Seth, Viv Vignoles, Rupert Brown, and Hanna Zagefka. 2014. The identity dynamics of acculturation and multiculturalism: Situating acculturation in context. In The Oxford Handbook of Multicultural Identity. Edited by Verónica Benet-Martínez and Ying-yi Hong. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sénéchal, Monique, and Jo-Anne LeFevre. 2002. Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five-year longitudinal study. Child Development 73: 445–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sénéchal, Monique, and Jo-Anne LeFevre. 2014. Continuity and change in the home literacy environment as predictors of growth in vocabulary and reading. Child Development 85: 1552–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sénéchal, Monique. 2006. Testing the home literacy model: Parent involvement in kindergarten is differentially related to grade 4 reading comprehension, fluency, spelling, and reading for pleasure. Scientific Studies of Reading 10: 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, Monique, Whissell Josée, and Ashley Bildfell. 2017. Starting from home: Home literacy practices that make a difference. In Theories of Reading Development. Edited by Kate Cain, Donald Compton and Rauno Parrila. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 383–408. [Google Scholar]

- Shohamy, Elana. 2006. Language Policy: Hidden Agendas and New Approaches. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Silinskas, Gintautas, Noona Kiuru, Asko Tolvanen, Pekka Niemi, Marja-Kristiina Lerkkanen, and Jari-Erik Nurmi. 2013. Maternal teaching of reading and children’s reading skills in grade 1: Patterns and predictors of positive and negative associations. Learning and Individual Differences 27: 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwarchuk, Sheri-Lynn, Carla Sowinski, and Jo-Anne LeFevre. 2014. Formal and informal home learning activities in relation to children’s early numeracy and literacy skills: The development of a home numeracy model. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 121: 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Tuhiwai Smith. 2013. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Christmas, Cassie. 2020. Child agency and home language maintenance. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development. Edited by Andrea C. Schalley and Susana A. Eisenchlas. Berlin and Boston: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 218–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, Alison, and Elaine Reese. 2012. From reminiscing to reading: Home contributions to children’s developing language and literacy in low-income families. First Language 33: 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2004. Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2007. Towards a Theory of Language Policy. Working Papers in Educational Linguistics 22: 1–14. Available online: http://repository.upenn.edu/wpel/vol22/iss1/1 (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2009. Language Management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stavans, Anat, and Charlotte Hoffmann. 2015. Multilingualism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stavans, Anat, and Eva Lindgren. 2021. Building the multilingual literacy bridge. In Multilingual Literacy. New Perspectives on Language and Education 85. Edited by Esther O. Breuer, Eva Lindgren, Anat Stavans and Elke van Steendam. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 356–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, Christine, Olivia Stevenson, and Claire Adey. 2013. Young children engaging with technologies at home: The influence of family context. Journal of Early Childhood Research 11: 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Lisa K., Judith K. Bernhard, Suchi Grag, and Jim Cummins. 2008. Affirming plural belonging: Building on students’ family-based cultural and linguistic capital through multiliteracies pedagogy. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 8: 269–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bogdan, and Marjorie L. De Vault. 2016. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource. Oxford: Wiley Publications. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2016. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656 (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Van Tubergen, Frankvan, and Ineke Maas. 2007. Ethnic intermarriage among immigrants in the Netherlands: An analysis of population data. Social Science Research 36: 1065–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermaas-Peeler, Maureen, Bianca Sassine, Carly Price, and Caitlin Brilhart. 2011. Mothers’ and fathers’ guidance behaviours during storybook Reading. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 12: 415–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Kelly, and Lisa Wolf-Wendel. 2004. Academic motherhood: Managing complex roles in research universities. The Review of Higher Education 27: 233–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westeren, Ingelin, Anne Marie Halberg, Heloise Marie Ledesma, Astri Heen Wold, and Brit Oppedal. 2018. Effects of mother’s and father’s education level and age at migration on children’s bilingual vocabulary. Applied Psycholinguistics 39: 811–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willig, Carla. 2008. Introducing Qualitative Research in Psychology. Adventures in Theory and Method, 2nd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Suzanna. 2015. Mobile digital devices and preschoolers’ home multiliteracy practices. Language and Literacy 17: 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert. 2014. Case Study Research. California: SAGE Publication, Inc. [Google Scholar]

| Participants | Mixed Russian-CG | Immigrant Russian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 40 | 40 | |

| Age | Mean | 33 | 31 |

| Min. | 29 | 28 | |

| Max. | 45 | 43 | |

| SD | 2.1 | 1.9 | |

| LoR | Mean | 11.5 | 5.9 |

| Min. | 1 | 1 | |

| Max. | 16 | 13 | |

| SD | 3.99 | 5.21 | |

| AoO | Mean | 31.2 | 29.5 |

| Min. | 27 | 28 | |

| Max. | 44 | 42 | |

| SD | 3.2 | 3.6 | |

| Children | Mixed Russian-CG | Immigrant Russian | |

| Age | Mean | 9.3 | 8.1 |

| Min. | 2 | 2 | |

| Max. | 16 | 16 | |

| SD | 3.51 | 2.9 | |

| Gender | Male | 25 | 19 |

| Female | 15 | 21 | |

| Mixed Russian-CG | Immigrant Russian | |

|---|---|---|

| Do all your children speak and comprehend Russian? | ||

| Yes | 85% | 90% |

| No | 10% | 5% |

| No answer | 5% | 5% |

| Are you satisfied with their level of Russian? | ||

| Yes | 52.50% | 86% |

| No | 32.50% | 9% |

| No answer | 15% | 5% |

| Do your children refuse to use/speak Russian? | ||

| Yes | 30.50% | 5% |

| No | 66.50% | 90% |

| No answer | 3% | 5% |

| Can all of your children read and write in Russian? | ||

| Yes | 72.50% | 80% |

| No | 25% | 13.50% |

| No answer | 2.50% | 6.50% |

| Have you ever been advised by an expert to stop speaking Russian with your children? | ||

| Yes | 7.50% | 97% |

| No | 87.50% | 3% |

| No answer | 5% | 0% |

| Mixed Russian-CG | Immigrant Russian | |

|---|---|---|

| Which kindergarten/school does your child attend? | ||

| Public (Greek) | 82% | 10% |

| Private (English) | 11% | 73% |

| Private (Russian) | 7% | 10% |

| Private (Greek) | 0% | 7.50% |

| Do you think that your child is discriminated at kindergarten/school because he/she speaks Russian? | ||

| Yes | 7.50% | 3% |

| No | 85% | 94% |

| No answer | 7.50% | 3.00% |

| Does your child attend extra curriculum activities, classes? | ||

| Yes | 75% | 70% |

| No | 15% | 20% |

| No answer | 10% | 10% |

| Which languages are used there? | ||

| Russian | 25% | 23.52% |

| Greek | 30% | 35.29% |

| English | 27.50% | 41.19% |

| French | 7.50% | 0% |

| German | 10% | 0% |

| Do your children attend classes of the Russian language? | ||

| Never | 7.50% | 0% |

| Seldom | 7.50% | 10% |

| Sometimes | 7.50% | 0% |

| Often | 37.50% | 60% |

| Very often | 32.50% | 30% |

| No answer | 7.50% | 0% |

| Mixed Russian-CG | Immigrant Russian | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you try to teach your children the Russian language (words, grammar)? | ||

| Never | 2.50% | 0% |

| Seldom | 17.50% | 0% |

| Sometimes | 7.50% | 0% |

| Often | 32.50% | 40% |

| Very often | 30% | 50% |

| No answer | 10% | 10% |

| Which books/educational resources do you have at home? | ||

| Russian | 32.00% | 73% |

| Greek | 55.00% | 8% |

| English | 10.00% | 20% |

| Other languages | 3.00% | 2% |

| How often do you insist that your child uses Russian at home? | ||

| Never | 27.50% | 50% |

| Sometimes | 10% | 0% |

| Often | 25% | 20% |

| Very often | 25% | 30% |

| No answer | 12.50% | 0% |

| How often do you insist that your child uses Russian outside home? | ||

| Never | 45% | 50% |

| Seldom | 20% | 20% |

| Sometimes | 17.50% | 10% |

| Often | 7.50% | 20% |

| Very often | 2.50% | 0% |

| No answer | 7.50% | 0% |

| How often do you insist that your child takes part in the Russian activities, related to the Russian culture? | ||

| Never | 17.50% | 40% |

| Seldom | 27.50% | 10% |

| Sometimes | 20% | 20% |

| Often | 22.50% | 30% |

| Very often | 5% | 0% |

| No answer | 7.50% | 0% |

| Mixed Russian-CG | Immigrant Russian | |

|---|---|---|

| Code skills in Russian | ||

| Didactic approach | ||

| Teaching letter names | 68.00% | 82% |

| Practicing letter writing | 73.00% | 89% |

| Practicing name writing | 70% | 90% |

| Having the child pointing out letters or words in printed material | 75% | 91.50% |

| Correcting the child’s pronunciation | 42.50% | 75% |

| Exposure approach | ||

| Playing letter games | 53% | 66% |

| Playing rhyming games | 44% | 62% |

| Reciting nursery rhymes | 31% | 58% |

| Singing songs | 69% | 85% |

| Oral language skills in Russian | ||

| Didactic approach | ||

| Teaching the meaning of new words | 66% | 88% |

| Having the child repeat new words | 72% | 94% |

| Correcting the child if it uses a word incorrectly | 44% | 90.50% |

| Exposure approach | ||

| Shared reading | 41% | 67% |

| Storytelling | 39% | 58% |

| Listening to stories the child tells you | 27% | 52% |

| Talking with your child about the child’s experiences | 64% | 79.50% |

| Singing songs | 69% | 85% |

| Multimodality | ||

| Helping the child to use a tablet, a laptop, a computer | 85% | 82.50% |

| Watching television together | 97% | 95.50% |

| Multiliteracy | ||

| Drawing together | 32% | 58% |

| Visits to the library | 18% | 29% |

| Listening to music | 60.50% | 82% |

| Playing games | 44% | 57.50% |

| Using gestures | 71% | 86% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karpava, S. The Effect of the Family Type and Home Literacy Environment on the Development of Literacy Skills by Bi-/Multilingual Children in Cyprus. Languages 2021, 6, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020102

Karpava S. The Effect of the Family Type and Home Literacy Environment on the Development of Literacy Skills by Bi-/Multilingual Children in Cyprus. Languages. 2021; 6(2):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020102

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarpava, Sviatlana. 2021. "The Effect of the Family Type and Home Literacy Environment on the Development of Literacy Skills by Bi-/Multilingual Children in Cyprus" Languages 6, no. 2: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020102

APA StyleKarpava, S. (2021). The Effect of the Family Type and Home Literacy Environment on the Development of Literacy Skills by Bi-/Multilingual Children in Cyprus. Languages, 6(2), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020102