Abstract

This paper intends to provide some speculative remarks on how consistency and continuity in language use practices within and across contexts inform heritage language acquisition outcomes. We intend “consistency” as maintenance of similar patterns of home language use over the years. “Continuity” refers to the possibility for heritage language speakers to be exposed to formal education in the heritage language. By means of a questionnaire study, we analyze to what extent Italian heritage families in Germany are consistent in their use of the heritage language with their children. Furthermore, by analyzing the educational offer related to Italian as a heritage language across different areas in Germany, we reflect on children’s opportunities to experience continuity between home and school language practices. Finally, we interpret the results of previous studies on Italian heritage language acquisition through the lens of consistency and continuity of language experience. In particular, we show that under the appropriate language experience conditions (involving consistency and continuity), heritage speakers may be successful even in the acquisition of linguistic phenomena that have been shown to be acquired late in first language acquisition.

1. Introduction

One of the main challenges for research on the acquisition of a heritage language (HL, henceforth) has been to account for the enormous variation observed in language outcomes across HL speakers (Polinsky and Kagan 2007; Kupisch and Rothman 2018). Great attention has been devoted to how quantity and quality of language experience motivate variation in acquisition outcomes across different linguistic domains, including vocabulary knowledge (e.g., Thordardottir 2011), morphosyntax (e.g., Chondrogianni and Marinis 2011; Daskalaki et al. 2019; Unsworth 2013) and syntax–discourse interface phenomena (e.g., Paradis and Navarro 2003; Torregrossa et al. 2019, 2021).

The aim of this contribution is to draw attention to some features of heritage speakers’ language experience that may be crucial in determining individual variation in their language outcomes, focusing on the role of consistency and continuity of language experience within and across different contexts (home and school). Through the lens of these two notions (consistency and continuity), we analyze some aspects of the language practices of Italian HL communities in Germany. First, we consider demographic and sociolinguistic aspects related to these communities, focusing on children’s educational support outside the home (Section 2). Second, we report some information related to families’ home language practices by reviewing some questionnaire data reported in two previous studies on Italian heritage children in Cologne and Hamburg (Section 3). Finally, we offer some speculative remarks related to how consistency and continuity of language experience (or lack thereof) may account for (at least) some aspects of the linguistic behavior of Italian heritage speakers living in Germany, as described in previous studies (Section 4). Throughout the paper, we assume Rothman’s (2009, p. 156) definition of an HL as “a language spoken at home or otherwise readily available to young children, and crucially this language is not a dominant language of the larger (national) society” (cf. also Kupisch and Rothman 2018). Before proceeding with the rest of the discussion, we define the notions of consistency and continuity of language experience, which are central to this contribution.

Throughout the literature on bilingual language acquisition, the notion of consistency in language use has been mainly used to describe parents’ choice to use only one language when interacting with the child across different contexts. One example is the use of the “one parent, one language” (OPOL) strategy (Döpke 1992) where one parent speaks the HL with the child, and the other the majority language (e.g., Juan-Garau and Pérez-Vidal 2001; Takeuchi 2006). Some studies have shown that consistent adherence to the OPOL strategy affects HL acquisition positively. This has been observed in particular among children who are explicitly corrected or asked for reformulation by their parents whenever they do not use the appropriate language (Kasuya 1998; Lanza 1997; Mishina-Mori 2011). Consistent language input at home has also been shown to be crucial for the acquisition of an HL among children coming from families in which both parents use a minority language, as do most of the families considered in this contribution (De Houwer 2007; Kouritzin 2000; Pan 1995).

However, several studies have questioned this “strict” notion of consistency in parent–child interactions, whereby each parent uses only one language. On the one hand, De Houwer (2007) showed that the OPOL strategy is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for fostering children’s HL use (and, possibly, their language proficiency). Family contexts in which parents speak both the heritage and the majority language may lead to a successful acquisition of the HL, too. On the other hand, some studies have revealed inconsistencies between parents’ beliefs concerning language use at home (e.g., the idea that the parents use only one language when interacting with the child) and their actual practices (García and Wei 2014; Liang 2018; Schwartz 2008). In fact, most parents use language mixing, given that they are often bilingual themselves (Byers-Heinlein 2013). Furthermore, observations of parent–child interactions have revealed that parents’ pattern of language use at home is only one among several factors affecting home language use. Children’s language preferences, as well as contexts of use (e.g., meal-time conversations vs. interactions about school homework), seem to play a relevant role, too (Wilson 2020).

In general, we would like to argue that speaking the majority language at home does not necessarily have a negative impact on the acquisition of the HL. Indeed, it has been shown that bilingual children can share language and literacy skills across the HL and the majority language (Cummins 1979; Francis 2012). Therefore, the relationship between language input and language proficiency is not a linear one (i.e., the greater is the input in a language, the better the children’s proficiency is). In fact, recent studies show that HL acquisition may even benefit from exposure to the majority language. This has been observed in particular in schools in which the HL is the main medium of instruction, such as the Lycée Français de Hambourg (Germany), the Düsseldorf Greek-German school (Germany), and the Italian school of Athens (Greece), as described in Kupisch et al. (2014a, 2014b), Bongartz and Torregrossa (2020), and Torregrossa et al. (forthcoming), respectively. Exposure to the majority language (even if it is the minority language at school) supports the child in the development of linguistic and metalinguistic skills in both the heritage and the majority language by engaging the child in implicit or explicit comparisons between the two languages (cf. Torregrossa et al. forthcoming).

Another sense in which the term “consistency” has been used in the literature relates to adult speakers’ use of variable forms for the same linguistic function. From the learner’s point of view, these forms may lead to conflicting grammatical representations. An example is the possible omission of the do auxiliary in English questions (e.g., “(Do) You wanna play?”—see Miller and Hendricks 2014). Heritage children may be exposed to a greater amount of inconsistent input in their HL compared to monolingual children, especially if some family members (or members of their community) are bilingual, given that optionality is particularly attested in this group of speakers (Sorace 2011). With respect to the effect of inconsistent input on bilingual/heritage children’s learning outcomes, it has been shown that bilingual/heritage children are generally able to cope well with inconsistent input and extract relevant linguistic patterns in spite of “noisy” information (de Bree et al. 2017; see Antonijevic et al. 2019 for an exception to this generalization).

Children may also receive inconsistent input in the majority language. This is usually the case for those parents who are native speakers of the HL but, nevertheless, speak to the child in the majority language (their second language). This strategy obviously works to the detriment of the HL—due to the reduced amount of input in this language—and does not seem to be relevant for the acquisition of the majority language either, to which the child is exposed outside the home across different contexts over time (Hammer et al. 2009; Place and Hoff 2011). The occurrence of language shifts from the heritage to the majority language emerges from the analysis of the questionnaires targeting home language practices as reported in Section 3 and, as we will observe, may have a negative impact on children’s language learning and use of the HL.

Based on the abovementioned observations, we would like to introduce a different interpretation of the notion of consistency. It goes beyond the strict adherence to the OPOL strategy (which does not necessarily lead to successful acquisition) and optionality in the input to the child (with which the child is able to cope). We intend consistency in language use as the maintenance of home language use patterns over time (from birth to current age). Crucially, this definition includes the situation in which the HL is (consistently) exclusively spoken at home by one or both parents, but it also considers situations in which the HL is only part of the family language constellation (as described above). Under this new perspective, consistency in language use implies that over the years, shifts in patterns of language use in the family should occur as little as possible. We propose that consistency—as defined here—should be considered as a crucial factor for successful acquisition of an HL, as long as the family environment provides sufficient input to support the HL. To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated whether, when subjected to different patterns of HL use in the family, the maintenance of these patterns over the years has positive consequences for children’s acquisition outcomes in the HL. However, some preliminary evidence for the importance of consistency over time emerges from the analysis of the questionnaires reported in Section 3.

Along with consistency in language use in the family, we would like to include an additional dimension, which is related to the continuity between language practices at home and at school. This results from the implementation of school curricula in which children have the possibility to be exposed to the HL. The range of possible implementations of these curricula varies from schools in which the HL is taught as a foreign language to schools in which it is a medium of instruction (Bongartz and Torregrossa 2020). At the current state of knowledge, we are not able to establish how much literacy exposure at school is needed to attain “success” in the acquisition of an HL (cf. Kupisch and Rothman 2018 for a similar consideration). However, some recent studies showed that children’s language and literacy skills in both the heritage and the majority language may be fostered even in “monolingual” state schools, in which the majority language is taught through a multilingual lens, i.e., through pupils’ HL (Cantone 2020; Carbonara and Scibetta 2020; Cummins and Persad 2014; Cummins 2019). Therefore, the notion of continuity between home and school language guide our next observations related to the language and literacy practices of Italian HL children in Germany. We focus on the offer of bilingual education across different areas of Germany and on the continuity of this offer across school grades.

2. The Italian Community in Germany: Demographic Information on Adults and Children and the Bilingual Educational Offer

The following section takes the educational offer in Germany into account in terms of its support of Italian as an HL. In particular, we considered whether the number of German-Italian bilingual schools in certain areas matches the number of Italian children registered in the same areas (with special reference to the situation in North Rhine-Westphalia and Hamburg, respectively) and whether the German-Italian bilingual educational offer is continuous across school years (i.e., from primary to secondary schools). Before presenting this information, we provide general information on the presence of Italians in Germany, focusing our attention on Italian children.

2.1. The Italian Community in Germany: General Demographic Information

At the end of 2019, the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis 2020) counted 646,460 foreign residents in Germany holding an Italian passport, which makes Italians the fourth biggest community in the country, only preceded by Turkish, Polish, and Syrian citizens. The current Italian community is the result of two waves of immigration: The first took place in the second half of the 20th century and involved low-qualified workers (together with their descendants), whereas the second group was of the so-called newcomers who moved to Germany in the 2010s.

The history of Italian immigration to Germany started in the 1950s, after the two countries signed a mutual agreement in 1955 to favor the migration of Italian male workers to be employed in fast-growing German industry. The agreement was part of the immigration policy developed by West Germany to meet the need for low-skilled labor in the booming post-war economy. The project included recruitment agreements with several countries, among which were Spain, Greece, and Turkey (the last one was the country where the highest number of immigrants set off from). The premise of these agreements was that planned rotation cycles would limit the time that a single immigrant could stay in Germany. Therefore, foreign workers were referred to as Gastarbeiter, namely, guest workers, who would reside in Germany only for work-related reasons and then go back to their country of origin (Schmid 2014), eventually leaving their job position vacant for other incoming foreign workers.

Starting from the late 50s, the number of Italian Gastarbeiter in Germany increased at a fast pace until, in 1973, the German government decided to stop this immigration policy. In that year, there were 450,115 Italians living in Germany, and, after the program stopped, the number of Italian workers making their way back to their home country started to exceed the number of new arrivals, thus initially reducing the Italian population in Germany (Pichler 1997). However, the decrease was very smooth and progressive because in the meantime many Italian workers had established themselves in Germany and decided to stay in the country with their families. The following decades were characterized by a relatively stable presence of Italians in Germany, with the community not undergoing any major increase nor decrease. By 2009, only 56.6% of the Italian citizens in Germany had lived through a migration experience themselves, and the remaining 43.4% were born in Germany (Schmid 2014). This meant that the community was growing mainly due to the second- or third-generation descendants of the first immigrants. The tendency was inverted in 2012, when, as an effect of the economic crisis hitting Southern Europe, migration from Italy to Germany started to grow at a fast pace again. In 2009, 517,000 Italians lived in Germany; three years later, in 2012, the number had increased up to 529,000, showing a tendency that would be confirmed throughout the decade (the latest data disclosed by Destatis reported 646,640 Italians living in Germany at the end of December 2019).

The new wave of migration differed sharply from the previous one in terms of education, skills, gender, and destination. In the past, Gastarbeiter mainly settled around the big industrial centers located in Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, and North Rhine-Westphalia (i.e., southern and northwestern Germany). The most recent wave of migrants also targeted big cities, whose economy is based mainly on the service industry rather than manufacturing. For instance, in 2015 the number of Italian residents in Germany increased on average by 5.5% with respect to the previous year, but the phenomenon was particularly visible in cities such as Berlin, which alone registered a remarkable +17%. Gabrielli (2016) reported that in 2015, 24.9% of Italians in Hamburg and 35.1% of Italians in Bremen had been living in Germany for less than three years. Therefore, the substantial increase of Italian presence together with the selection of new destinations favors the emergence and enlargement of new communities, which, in turn, display different socioeconomic (and possibly also sociolinguistic) characteristics with respect to the older communities. Low-skilled workers with no education have been replaced by educated professionals: According to the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT 2018), all Italians who migrated to Germany in 2017 at the age of 25 or older had completed secondary school; among them, 26.4% held a bachelor’s degree (if not a higher academic qualification). At the socioeconomic level, Pichler (2019) reported higher rates of employment among Italian women in cities such as Berlin and Hamburg with respect to the older communities established around industrial cities. Pichler interpreted this as a sign of meaningful change in the community profile: Whereas in the past, male workers planned to spend only a few years abroad, from which they could better economically support their family in the home country, nowadays migration is often planned as a long-term project that involves the whole family.

2.2. The Presence of School-Age Italian Children in Germany

The Italian community also includes many citizens under the age of 18; some of them were born in Italy and moved to Germany with their parents, whereas many others are second- or third-generation children who were born in Germany with at least one parent holding an Italian passport.

On 31 December, 2019, Destatis (2020, p. 35) registered the presence of 14,930 Italian citizens under the age of 5, 14,595 children between 5 and 9, 14,430 between 10 and 14, and 19,400 teenagers between 15 and 19 years old in Germany.

In its annual report on School and Culture 2018/2019, Destatis (2019) reported the presence of 36,171 Italian pupils in German public schools (kindergartens excluded): The majority of them lived in Bavaria (6078), North Rhine-Westphalia (8116), or Baden-Württemberg (10,657); Baden-Württemberg was also the region with the second-highest incidence of Italian pupils in the overall school population (0.95%), only preceded by Saarland (0.99%, corresponding to 910 Italians out of 91,247 pupils in the region).

We took these data on the presence of Italian pupils in German schools as an index of the potential demand for German-Italian bilingual education programs throughout the country. However, we would like to point out that the numbers might be underestimated: The above data do not consider children coming from families with an Italian linguistic and cultural background if they hold a German passport. In this case, children are registered in schools as German citizens. Therefore, official data on the incidence of Italian pupils in the school population might not entirely reflect the actual presence of children with Italian backgrounds in German schools.

2.3. The German-Italian Bilingual Educational Offer in Germany

Over the last decades, immigrant communities have developed some degree of awareness of the academic advantages and intellectual benefits provided by HL acquisition and literacy in the HL (Liang 2018). Many parents are afraid that the input they provide at home is insufficient for successful HL acquisition and see their lack of time and energy as the main limitation to HL maintenance in the family. At the same time, there is an increasing consensus among parents that bilingual schools and community networks (e.g., church) are crucial resources to support HL maintenance. Tse (2001) claims that successful HL maintenance is related to language vitality, which is achieved through synergetic cooperation among peer groups, institutions, and parents. For instance, the institutional offer in terms of bilingual schools can positively affect families’ attitude towards the HL by making them feel more supported and recognized as a community.

The schooling needs of different Italian communities have led to the implementation of German-Italian bilingual programs in public and private schools. The distribution of bilingual schools clearly matches the information on the first wave of immigration in the 20th century: All schools featuring a German-Italian bilingual program (with the exceptions of those in Berlin) are located in or around the industrial centers that used to attract foreign workers to West Germany (Table 1). One example is Wolfsburg in Lower Saxony, which is well known for being one of the major production sites for cars in the country. In contrast, we are not aware of any bilingual program in regions that used to be part of former East Germany.

Table 1.

Number of elementary and secondary schools implementing German-Italian bilingual programs in different federal states of Germany. In brackets: number of schools in Cologne among the ones in North Rhine-Westphalia.

Although it was not possible to estimate the exact demand of German-Italian bilingual education in relation to the existing offer, we tried to draw some observations from demographical statistics and compared the two areas in which we conducted our questionnaire study (Section 3), namely, Cologne (the biggest city in North Rhine-Westphalia) and Hamburg (also the capital of the homonymous federal state). Data published by Destatis allowed for a comparison between the two federal states despite their many dissimilarities. North Rhine-Westphalia is one of the biggest federal states and has around 18 million inhabitants, whereas Hamburg is, by extension, among the smallest federal states and has ca. 2 million inhabitants. The former is home to 143,110 Italians, among which 8116 are pupils; the latter is home to 7725 Italian citizens, among which 474 are pupils. Notwithstanding the different sizes of the two federal states, the two communities potentially have the same demands when it comes to bilingual education because the school-age population represents 5.6% of the overall Italian population in North Rhine-Westphalia and 6.1% in Hamburg. In other words, although Italian migration to Hamburg is more recent than to North Rhine-Westphalia, the number of children and teenagers is comparable across the two areas, which implies similar education needs in the two communities. The analysis of the bilingual educational offer in Hamburg is straightforward since the city has only one elementary school for 474 potential users. As for North Rhine-Westphalia, the 8116 Italian pupils living in this federal state are the potential user base of seven schools offering a bilingual program, with a ratio of 1159 children per school (i.e., more than double compared to Hamburg). On top of this, the offer is quite scattered in North Rhine-Westphalia. For instance, Cologne currently has three elementary schools, but no secondary school (the school in which we collected questionnaires does not offer the bilingual program anymore; currently, the closest secondary school is about 20 km away from Cologne). At present, despite a relatively wide offer in terms of bilingual education in elementary school, there is no real possibility for pupils in Cologne and Hamburg to further pursue a bilingual education at the secondary level.

With respect to the general offer of German-Italian bilingual programs, we also want to point out that a new tendency is visible in some areas of the country: According to the list made available by the Italian Embassy in Germany, there are at least 12 German-Italian bilingual kindergartens in Berlin, but only two elementary schools and two secondary schools that offer German-Italian bilingual education. The flourishing of so many initiatives promoting bilingual daycare centers for preschool children seems to be in line with the image of Berlin as the site of a fast-growing community including many young families and it is also a clear sign of interest in bilingual education by many families. However, these demands might not be met once children turn six, due to the scarcity of German-Italian bilingual schools at the elementary and (later) at the secondary level. Based on demographic data and the observation of the currently available educational opportunities, in the next few years we might expect to observe a sharp increase of elementary schools offering bilingual programs in Berlin; this would guarantee continuity in linguistic education after kindergarten.

With respect to the kind of programs adopted by German-Italian bilingual schools, we found rather homogeneous offers across regions. Most schools, including those in Cologne and Hamburg, named their program bilingualer Zweig, i.e., “bilingual branch” or “sector.” This kind of program is characterized by (i) Italian classes from the first year on; (ii) five teaching hours per week focusing on the Italian language: pupils are supposed to learn to read and write in Italian and German in parallel; (iii) teaching hours in Italian distributed equally throughout the week, i.e., one hour of Italian per day; and (iv) additional hours (three on average) in Italian for the so-called Sachunterricht (“content class”), including social studies and sciences (e.g., history, geography, or biology); the subjects that are taught in Italian vary from grade to grade and school to school (although math is usually taught in German). In general, each language is taught by different teachers and, hence, the bilingual program implies two monolingual curricula, rather than being based on a single multilingual one (see also García 2009 for an extensive criticism of monolingual assumptions underlying bilingual programs). Moreover, some school websites report that certain classes are jointly conducted by two teachers, one responsible for Italian and the other for German. On those occasions, the Italian and German teachers should both be present simultaneously in the class in order to provide pupils with input in the two languages1. The curricula of the bilingual schools in Cologne and Hamburg were designed in compliance with the guidelines outlined above.

In conclusion, three key observations emerged from the analysis of the current offer of bilingual education. First, German-Italian bilingual education is available both in the regions that were targeted by the first wave of immigrants and in cities that are hosting the second and more recent wave. Despite demographic and social differences, both communities seem to be determined to maintain a link with their country of origin and attempt to foster this bond in the younger generations through formal education in the HL. We interpret these data as a clear tendency to establish a certain continuity between home and school language-use patterns. Second, the ratio between the number of Italian pupils and the offer of bilingual education varies across communities. Compared to the poor and scattered offer in North Rhine-Westphalia, Italian families in Hamburg receive a richer offer. This translates into easier access to a bilingual education that guarantees continuity between home and school language practices. Third, both communities lack continuity across school levels: Neither in Cologne nor in Hamburg can pupils pursue a bilingual education after elementary school, since there are no German-Italian curricula offered at the higher secondary level in those areas.

After considering whether children in different areas of Germany have the possibility of receiving continuous exposure to the HL from home to school in this section, in the next section we account for families’ consistency of language use patterns over the years.

3. Home Language Practices among Italian Heritage Speakers: A Critical Review of Two Questionnaire Studies in Cologne and Hamburg

In this section, we aim to identify patterns of family language use based on a review of the questionnaire information collected in Cologne (Torregrossa and Bongartz 2018) and Hamburg (Listanti and Torregrossa 2021). For the present study, we conducted a new analysis of these questionnaire data. Our aim was to show how family policies may vary across and within communities and to provide speculative remarks on how this variation is reflected in heritage children’s language outcomes.

We administered the questionnaire to 36 parents of children attending schools in which German is the main medium of instruction and Italian is offered as a secondary “branch” (bilingualer Zweig, see Section 2). A total of 18 parents were from Cologne and 18 from Hamburg.

For the present study, we considered five modules of the questionnaire (see A–E below), in addition to background information concerning the children and their family (i.e., the children’s age and birthplace and the family’s origin). We report the questions in their English translation.

- A.

- Parents’ Self-Rated Proficiency in Both Italian and German

This module addressed whether the families in Cologne and Hamburg differed from each other in their (self-rated) proficiency in Italian and German, and their connection to the heritage country. We asked the mother and the father to self-estimate their abilities in one language compared to the other (Which language do you think you speak better?). The respondents could choose between three options: “Italian,” “German,” or “both.”

- B.

- Children’s Home Language History

This module addressed the consistency of family language use from children’s birth until the age of 6. In particular, we asked about the amount of exposure that children received from birth to the age of 3, from 3 to 6 years old, and at 6 years of age (Do you remember which languages your child heard and used when s/he was a baby, until s/he was around 3 years old, between 3 and 6 years old, and when s/he was enrolled in school at 6 years old?). For each age stage, the respondents had to indicate which language(s) (“mainly German,” “mainly Italian,” or “both”) the children spoke with which person (“mother,” “father,” “siblings,” and “grandparents”; “teachers” and “classmates” starting from the age of 3).

For the analysis, we considered each age stage separately and derived a score for German and Italian corresponding to the number of persons speaking “mainly German” or “mainly Italian” with the child. For answers stating that both languages were used in equal proportion, we split the associated scores between the two languages. All scores corresponding to each age stage were expressed in proportion as the ratio between the language-specific score and the total score in the corresponding age stage (i.e., the number of persons with which the child spoke at least one language). Finally, we subtracted the score obtained in German from the score obtained in Italian. Thus, in each age stage (0–3, 3–6, and 6), a positive score indicated dominance of language use in Italian, whereas a negative score reflected dominance in German.

- C.

- Children’s Early Literacy

This module addressed children’s literacy exposure in the preliterate years. For each family member (“mother,” “father,” “siblings,” and “other”), we asked whether s/he read books to the child when the child was younger and in which language this happened (Did you read books with stories and fairy tales to your child when s/he was younger? If so, can you tell me in which language?). For the language(s), the options were again “mainly German,” “mainly Italian,” and “both.” For the analysis of this module, we followed the same procedure as described above.

- D.

- Children’s Current Language Use

This module addressed how children’s use of the two languages was divided between different activities. First we asked which language(s) the children used with which family member at the time of the interview, distinguishing between the input to the child (Who speaks which language with the child?) and the output of the child (Which language does the child use with which person?). As in the previous modules, the options for the languages were “mainly German,” “mainly Italian,” and “both.” For the persons, the options were “mother,” “father,” “siblings,” “grandparents,” and “friends.” The analysis followed the same procedure as indicated above. Second, we provided a list of different activities (remembering telephone numbers, talking to oneself, etc.) and asked which language the children spoke during this activity. For each language, we assigned 1 point for each activity in which the language was used (0.5 points if the indicated option was “both”). The final language-specific score was the ratio between the raw language-specific score and the total number of activities. Once again, we subtracted the score obtained in German from the score obtained in Italian.

The final score of the module corresponded to the mean between the first score (related to language use with family and friends) and the second score (related to language use across different activities).

- E.

- Children’s Self-Rated Proficiency in Both Italian and German

This module addressed how the children in the two cities evaluated their own linguistic abilities in the heritage and the majority language. One question prompted parents to ask their children how well they thought they could understand, speak, read, and write in the HL and the majority language (How well do you think you understand/speak/read/write in Italian/German?). The possible answers were “very well” (3 points), “well” (2 points), and “not very well” (1 point). To analyze the results, we derived two scores for each child, i.e., one concerning conversational abilities (understanding and speaking) and one concerning literacy-related abilities (reading and writing) as the mean of the scores assigned to each skill in the corresponding activity (conversational vs. literacy-related). For example, one child in Cologne answered that she understood Italian “very well,” spoke it “well,” and wrote and read in Italian “well.” Thus, she was assigned 2.5 points for conversational abilities and 2 points for literacy-related ones.

Results

Table 2 provides an overview of all the data extracted from the questionnaires while distinguishing between the two school locations (Cologne and Hamburg).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the different modules of the questionnaire across the two family groups (living in Cologne and Hamburg). The numbers corresponding to the modules related to dominance across different contexts refer to the difference between the score obtained in Italian and the score obtained in German in the corresponding module of the questionnaire, whereby a positive score indicates dominance in Italian and a negative score indicates dominance in German.

The children in Cologne attended a secondary school (from grade 5 to grade 7; mean age = 12; 11) and those in Hamburg attended a primary school (from grade 2 to grade 4, mean age 8; 10). The difference in age (one-way ANOVA: F(1,32) = 204.47, p < 0.001) is taken into account while discussing some results2.

In both groups, most children were born in Germany (13 children in Cologne and 12 in Hamburg). Four children in Cologne and 5 children in Hamburg were born in Italy and their mean age of arrival was 6;9 (ranging from 3 to 9 years) and 4;3 years (ranging from 3 months to 6;6 years), respectively. One parent in Cologne did not answer this specific question and one child in Hamburg was born in a different European country than Germany or Italy (age of arrival to Germany: 6 years). A Fisher’s exact test revealed that the distribution of the children according to their place of birth did not differ across the two groups (p = 1.00).

The two groups were similar with respect to family origin, too (Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.38): Some children came from families in which both parents were first-generation migrants from Italy (6 in Cologne and 5 in Hamburg), some from families in which one parent was a first-generation migrant and the other either a second-generation German-Italian bilingual or a native German monolingual speaker (10 in Cologne and 7 in Hamburg), and others from families in which both parents were second-generation speakers (2 in Cologne and 6 in Hamburg).

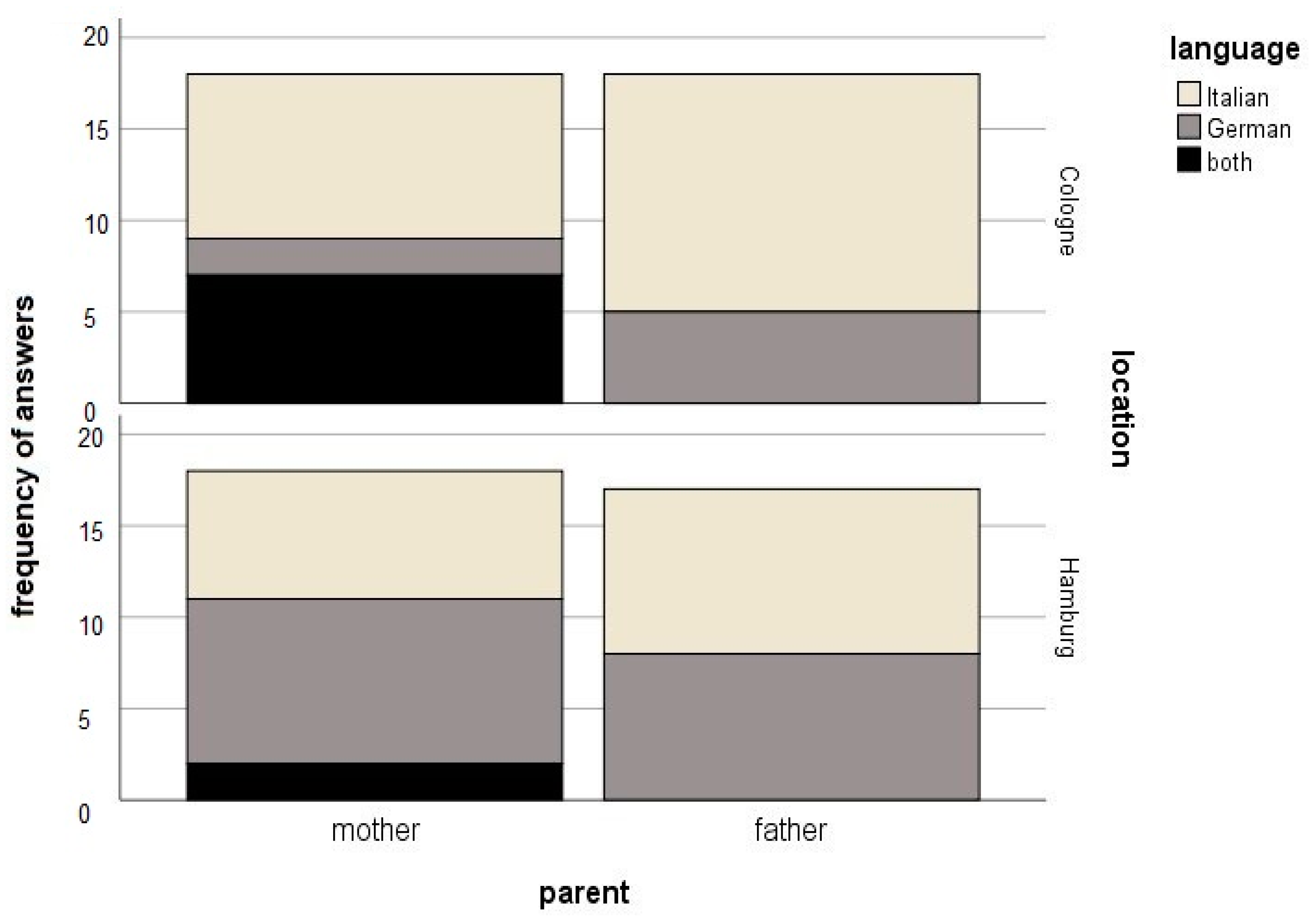

These different language constellations were reflected in the answers related to parents’ self-estimation of their abilities in one language compared to the other. Figure 1 reports the frequency of answers related to each language (with “German,” “Italian,” and “both”), considering both the fathers’ and mothers’ answers. On the one hand, the fathers in Cologne declared that they spoke better Italian (compared to German) more often than the fathers in Hamburg (13 vs. 9 answers), even if the difference between these two groups was not significant (χ2(1) = 1.39, p = 0.31). On the other hand, the mothers in Cologne differed from those in Hamburg, since they answered more frequently that they spoke better Italian (9 vs. 7 answers) or that their speaking abilities were the same in both languages (7 vs. 2 answers; Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.03).

Figure 1.

Frequency of occurrence of the answers “German,” “Italian,” and “both” to the question Which language do you think you speak better? The figure considers the answers given by the mothers and the fathers individually.

The data related to the families in our sample did not reflect the Italian migration history in the North Rhine-Westphalia and Hamburg area (as reported in Section 2), based on which we would have expected to observe a relatively greater number of second-generation families in Cologne than in Hamburg.

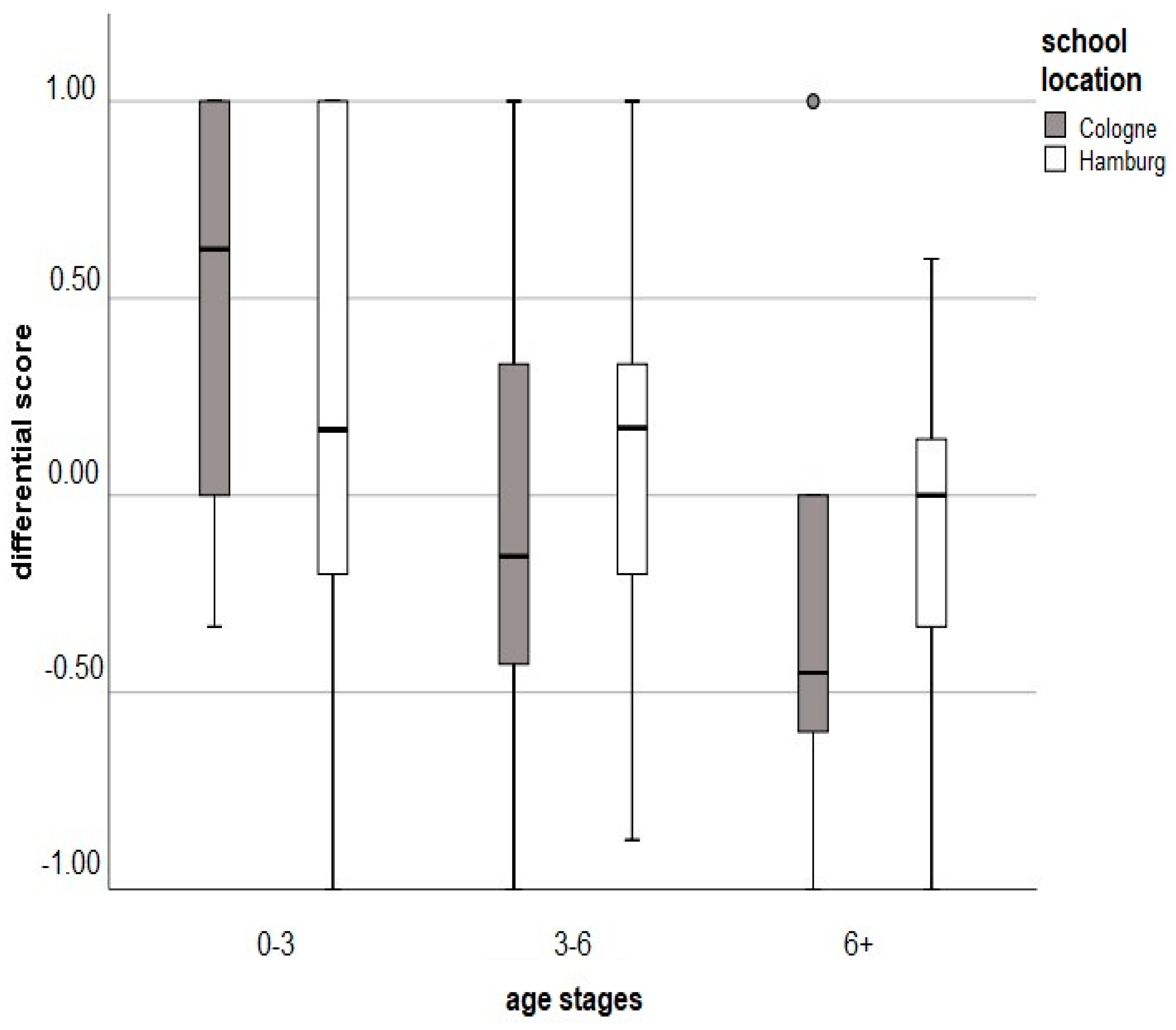

The first clear difference between the two groups (families in Cologne vs. families in Hamburg) emerges when considering home language use between 0 and 3 years old, 3 and 6 years old, and at 6 years old. We performed a mixed-design ANOVA with the three age stages as the within-subjects variables and location (Cologne vs. Hamburg) as the between-subjects variable. The analysis revealed a significant interaction between age stages and location (F(2,68) = 4.81, p = 0.01, η2 = 0.12). In particular, paired sample t-tests showed that in the Cologne group, the use of the HL decreased significantly from the age range 0–3 to the age range 3–6 (t(17) = 3.81, p < 0.001), whereas this was not the case for the Hamburg group (t(17) = 0.84, p = 0.41). At 6 years old, a significant decrease in the use of Italian at home could be observed in both groups (t(17) = 2.88, p = 0.01 for Cologne; t(17) = 2.59, p = 0.02 for Hamburg). Figure 2 represents the variation in home language use patterns across age stages in the two locations, Cologne and Hamburg.

Figure 2.

Box plot of the differential scores related to home language history across different age stages (from birth to 3 years old, from 3 to 6 years old, and at 6 years old) in the two groups of children (living in Cologne and Hamburg). The differential scores are calculated by subtracting the index related to the amount of language use in German (as extracted from the questionnaires) from the index related to the amount of language use in Italian, whereby a positive score indicates dominant language use in Italian and a negative score indicates dominant language use in German.

Therefore, the families in Hamburg in our sample appeared to be slightly more consistent in their use of the HL at home than the families in Cologne, since their home language use patterns remained more stable over the years. The observed difference between the two groups can hardly be ascribed to differences in family background since they pattern similarly with respect to the family’s origin (as noticed above), or to greater confidence in using German compared to Italian among the Cologne parents. In fact, we observed the exact opposite tendency in Figure 1. We propose that the observed language shift among the families from Cologne may be affected by the uncertainty with respect to whether their children will be able to attend a bilingual school later in life, given the limited offer in terms of bilingual education in Cologne. As noticed in Section 2, the ratio between the number of schools offering Italian as a second language and the number of children with an Italian background is lower in Cologne than in Hamburg.

Table 1 also reports the results related to the remaining three modules of the questionnaire (early literacy, current literacy, and current language use), categorized by location. Overall, the two groups appeared to be Italian-dominant in their early-literacy exposure and German-dominant in their current literacy and language-use practices. Therefore, the data indicate a shift in literacy practices between the past and the present for both groups. In other words, the parents engaged in literacy-related activities in Italian before the children went to school. However, the children preferred to conduct literacy activities in the dominant language of their school, i.e., German, once they were able to read for themselves. Based on one-way ANOVAs, we found no significant difference between the two groups in any of the three modules of the questionnaire (early literacy: F(1,34) = 0.61, p = 0.44; current literacy: F(1,34) = 0.32, p = 0.57; current language use: F(1,34) = 1.85, p = 0.18).

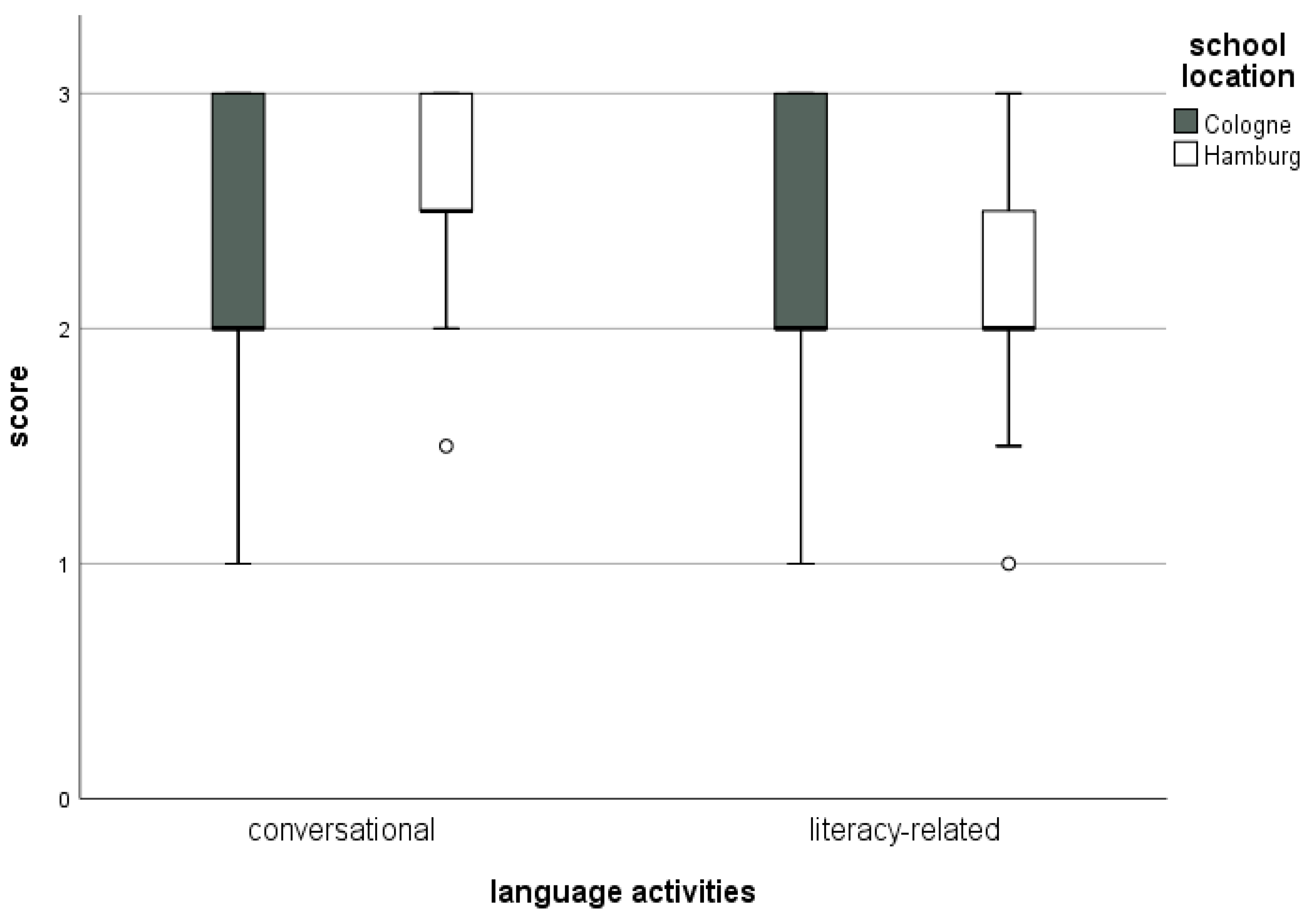

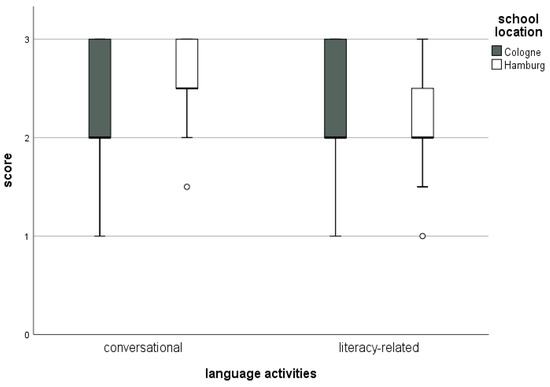

Finally, Figure 3 reports the box plots of the scores of the self-estimated skills related to conversational-related and literacy-related activities in the HL across the two groups of children (in Cologne and Hamburg). We performed a mixed-design ANOVA with the two types of activities (conversational-related and literacy-related) as the within-subjects variable and location (Cologne vs. Hamburg) as the between-subjects variable. The analysis revealed a significant interaction between type of activity and location (F(1,34) = 6.12, p = 0.02, η2 = 0.15). In particular, one-way ANOVAs revealed that although the two groups of children did not differ from each other in their self-estimated scores related to literacy-related activities (F(1,34) = 0.08, p = 0.79), the children in Hamburg appeared to be more confident in their language skills related to conversational activities (F(1,34) = 4.24, p = 0.05).

Figure 3.

Box plot of the scores of the self-estimated language abilities related to conversational-related (understanding/speaking) and literacy-related (reading/writing) activities across the two groups of children (living in Cologne and Hamburg).

Performing the same mixed-design ANOVA analysis as above with the scores of the self-estimated skills in German as the dependent variable, we found a significant effect for the type of activity (language use-related vs. literacy-related)—F(1,34) = 22.91, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.40—but no significant interaction between type of activity and location (F(1,34) = 0.79, p = 0.38, η2 = 0.02). In general, the children appeared to be more confident in their understanding and speaking skills than in their reading and writing skills in German (paired-sample t-test for the group in Cologne: t(17) = 2.83, p = 0.01; for the group in Hamburg: t(17) = 3.92, p < 0.001).

In conclusion, the questionnaire data revealed that children’s language practices in and outside the home were quite similar across the two groups (living in Cologne and Hamburg). We found a difference only in the extent to which the families were consistent in their language use over the years. In line with the definition formulated in Section 1, consistency requires maintenance of language use patterns over the years and does not necessarily correspond to greater use of the HL at home, as shown by the data reported in Figure 2.

More consistency in family language use may help to understand the increased confidence of the children in Hamburg, both for understanding and speaking the HL. However, this conclusion should be made with caution, given that the children in Hamburg were younger than those in Cologne (Table 1). It is thus not excluded that age may affect children’s degree of confidence related to their proficiency in the HL.

Among the children in Hamburg, the greater confidence in language abilities concerning conversational activities did not extend to literacy-related activities (reading and writing). Most likely, confidence in the latter domain can only be obtained by intensifying the use of the HL at school. However, higher confidence in language abilities related to conversational activities (as compared to literacy-related ones) was also observed in German, which may reflect that children generally perceive literacy-related activities as cognitively more challenging than conversational ones.

4. Effects of Consistency and Continuity of Language Experience on the Outcomes in the Heritage Language

This section aims to interpret some of the findings related to the language outcomes of Italian heritage speakers with German as the majority language based on the notions of consistency and continuity of language experience, as introduced in Section 1.

Our review includes studies concerning participants whose ages ranged from very early childhood to adulthood, in order to get a glimpse of the effects of consistency and continuity of language experience throughout the lifespan. Needless to say, some of our observations are speculative, since the data related to possible shifts in an individual’s language experience over time are often inaccessible due to the cross-sectional nature of these studies and to the fact that the assessment of speakers’ language experience is not central in many studies. Furthermore, we consider the nature of the linguistic phenomena being described as an additional factor contributing to variation in language acquisition and outcomes in the HL. For clarity’s sake, we group the reviewed studies according to the age of the bilingual participants, thus distinguishing between studies on preschool children, school-age children (at the elementary and secondary levels), and adults.

4.1. Studies on Italian Heritage Preschool Children

Several studies on Italian HL considered very young children, ranging from approximately 1;6 and 4;0 years of age (e.g., Cantone 2005; Eichler et al. 2012; Kupisch 2007; Müller and Hulk 2001; Schmitz and Müller 2008; Schmitz et al. 2011). The data were mainly drawn from a longitudinal corpus, including, among others, recordings of interactions between German-Italian children living in Hamburg and Italian interlocutors, as collected within a project on early bilingualism led by Natascha Müller. With respect to our main line of investigation, these studies are useful sources to understand which strategies some families use to raise children bilingually. All families considered in these studies adopted the OPOL strategy, with the father being a native speaker of German and the mother of Italian (except for one child’s mother who was bilingual). In some families, Italian was chosen as the home language in order “to strengthen the language without community support” (Kupisch 2007, p. 64).

The study by Cantone (2005) suggests that in these families, home language use was quite consistent over the years. The four children followed similar patterns of code-mixing (from German to Italian, and vice versa), independently of their dominance in one or the other language (see also Cantone 2007). In all cases, code-mixing gradually disappeared over the years. However, two children (one Italian dominant and one German dominant) exhibited a reappearance of code-mixing after the age of three, but only in the interactions in Italian. Interestingly, this age corresponds with the beginning of German kindergarten (Cantone 2007, p. 164). Therefore, this study seems to comply with our idea that lack of continuity in language experience affects language outcomes in the HL.

According to certain abovementioned studies, simultaneous bilingual acquisition (of Italian, with German as the other language) shows a similar developmental pattern as Italian monolingual L1 acquisition, with the possibility of observing a slight delay (cf. Kupisch 2007 on the acquisition of determiners). This is particularly evident when considering linguistic phenomena that are acquired early by Italian monolingual children, such as gender marking on determiners (Kupisch et al. 2002; Pizzuto and Caselli 1992). Eichler et al. (2012) reported that German-Italian bilingual children display very few gender errors, just like their monolingual peers.

This result is consistent with the idea that language exposure from birth is relevant for the acquisition of linguistic phenomena that emerge early in L1 (Tsimpli 2014; Schulz and Grimm 2019). In other words, the similar behavior of monolinguals and bilinguals observed by Eichler et al. (2012) is to be expected, since monolingual and simultaneous bilingual children are both exposed to Italian from birth. In contrast, Tsimpli’s theory predicts that children with a later age of onset will exhibit difficulties in gender marking on determiners compared to monolingual and simultaneous bilingual children.

Some other studies have revealed a quantitative difference between monolinguals and bilinguals. This is especially the case for investigations related to the acquisition of syntax–discourse interface phenomena, such as subject and object omission (or lack thereof). As for subject omission, Schmitz et al. (2011) observed that bilingual children produce more overt pronouns in the subject position than their monolingual peers (who prefer to omit subjects). As for object omission, Müller and Hulk (2001) found an overproduction of ungrammatical object omissions (instead of clitics) by bilinguals compared to monolinguals. In both cases, the difference between monolinguals and bilinguals was interpreted as a cross-linguistic effect from German to Italian: German does not generally allow for subject omission, but displays object-drop (cf. Belletti et al. 2007; Müller and Hulk 2001; and Serratrice et al. 2004 for different accounts of this cross-linguistic effect). Again, these data are in line with Tsimpli (2014), who argued that the acquisition of syntax–discourse interface phenomena (i.e., late phenomena, in her terms, as opposed to the abovementioned early ones) is sensitive to language input (rather than age of onset) effects. In other terms, the acquisition of these phenomena follows different patterns between bilinguals and monolinguals because in general, the former receive less input3.

As a summary of the studies reviewed thus far, two points are relevant for our discussion on how consistency and continuity in home language practices affect bilingual language outcomes in very young children. First, bilinguals may exhibit similar processes and pace of acquisition as monolingual children, even if their language input is divided between two languages. This holds true in particular for linguistic phenomena that are acquired early in L1 acquisition and are thus sensitive to age of onset (rather than input). Second, linguistic phenomena exhibit different sensitivity to input and possibly to consistency and continuity of language use across different contexts over the years.

4.2. Studies on Italian Heritage School-Age Children

The existing studies on Italian school-age children provide evidence in favor of the significant role played by language experience for the acquisition of certain linguistic phenomena. Notably, all phenomena described involve the interface between syntax and other linguistic domains. Kupisch and Pierantozzi (2010) investigated whether, in Italian, monolingual and bilingual children ranging in age between 6 and 11 years old differed in the interpretation of plural definite noun phrases as either specific or generic (a linguistic phenomenon at the interface between syntax and semantics) by means of a truth-value judgment task. Both readings are possible in Italian. The bilingual group did not have any problem in interpreting definite nouns as generic (this was even the preferred reading of this group), even if generic readings in German are expressed by using bare nouns. Importantly, neither variation in age nor dominance (in German) motivated variation in children’s interpretation preferences. Since the children of this study attended the bilingual school in Hamburg (cf. Section 2 and Section 3), the study suggests that continuity between home and school language-use practices contributes to the stable acquisition of this structure throughout the years, independently of the fact that, overall, children are German-dominant in their language experience in and outside of school. The same considerations apply to the acquisition of certain syntax–discourse interface phenomena, such as the alternation between post-verbal (in broad-focus sentences) and pre-verbal subjects (when the subject is a topic) of unaccusative verbs. The study by Listanti and Torregrossa (2021) showed that German-Italian bilingual children (between 7 and 11 years old) attending the abovementioned primary school in Hamburg mastered this alternation fully. Again, dominance and age did not seem to affect the results.

A different picture emerges when looking at the acquisition of other syntax–discourse interface phenomena in Italian, such as the post-verbal position of subjects carrying new information and the use of pronouns in narrative discourse, as shown by the abovementioned studies by Listanti and Torregrossa (2021) and Torregrossa and Bongartz (2018), respectively. The former study showed that children may produce (inappropriate) discourse-given post-verbal subjects of transitive verbs. The latter revealed that German-Italian bilingual teenagers attending a secondary school in Cologne tended to use overspecific, redundant referring expressions to maintain reference to story characters. Greater or lesser dominance in language experience in Italian emerged as a relevant factor for the acquisition of both phenomena. These results can be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, it may be argued that consistency and continuity in language experience over the years is not sufficient for the acquisition of certain syntax–discourse interface phenomena. On the other hand, it may be claimed that these phenomena are still developing, and that their acquisition only requires a greater amount of input. If this is the case, we expect bilinguals to master these phenomena later in life.

4.3. Studies on Italian Heritage Adults

Matching the evidence reported above concerning school-age children with studies on Italian adult heritage speakers may shed some new light on whether certain linguistic phenomena are successfully acquired by heritage speakers if they are consistently and continuously exposed to the heritage language throughout their lifespan.

As for the domain of reference use, Schmitz et al. (2016) and Di Venanzio et al. (2016) showed that Italian adult heritage speakers perform on a par with monolingual speakers with respect to the distribution of overt/null third-person singular subjects in discourse as well as the conditions for the use of object-drop. The authors reported that the participants of these two studies were exposed to Italian from birth by their parents (who were native speakers of Italian) and presumably received rich and consistent input over time. Moreover, they also attended formal courses of Italian as part of their after-school activities, thus receiving the opportunity to be exposed to more formal linguistic varieties. Therefore, this study suggests that consistency and continuity of language experience in Italian throughout the lifespan can lead to successful attainment of reference use in discourse.

As for the marking of new information by using post-verbal subjects, the study by Caloi et al. (2018) analyzed the answering strategies of Italian adult heritage speakers compared to those of monolinguals. The authors showed that whereas monolingual native speakers mainly provided VS answers, the heritage group also relied on the SV-order (which is the only possible strategy in German). The bilingual profiles (in terms of language exposure) of the heritage speakers considered in Caloi et al. (2018) appeared similar to the ones reported in Schmitz et al. (2016): Either one or both parents spoke with the participants in Italian from birth; as young adults (mean age 25;6), most of them still lived with their family of origin at the time of testing and used Italian on a daily basis as the family language (also in combination with German); plus, 20 out of 22 HL participants received formal education in Italian in bilingual programs, afternoon courses, and/or at the university level. Contrary to the studies by Schmitz and colleagues, the study by Caloi et al. (2018) showed that certain phenomena may involve residual optionality, even among speakers who were consistently and continuously exposed to the HL throughout the lifespan (cf. Sorace 2011 for similar considerations).

Recent studies in the field of second language phonology provided similar evidence by looking at the acquisition of a native accent by Italian heritage speakers. In Kupisch et al. (2014a) and Lloyd-Smith et al. (2020), Italian adult heritage speakers were perceived by Italian native speakers as native in their weaker language (Italian) at a rate that ranged from 30% to 50.8%, respectively. By contrast, they were always perceived as native in their stronger language (German). Overall, the age of onset of German does not have an impact on the global accent in the HL (Lloyd-Smith et al. 2020), indicating that simultaneous exposure to both languages from birth does not result in a poorer accent in the HL. Among the factors that lead to a positive outcome (i.e., the perception of a native accent), the authors mentioned the frequency of use of the HL across different contexts over time, which can be interpreted in terms of the notion of continuity as defined in this paper4. However, they also showed that the length of residence in Italy during childhood and adolescence seems to play a significant role, too—which is not included in our definition of continuity. This suggests that, as in the case of the abovementioned study by Caloi et al. (2018), the notions of consistency and continuity of language experience may not be sufficient for the acquisition of this particular phenomenon, either.

In contrast, relevant evidence in favor of our idea that consistency and continuity of experience to the HL enhances the acquisition of certain linguistic phenomena comes from the study by Kupisch (2012). The author showed that Italian adult HL speakers tend to interpret Italian definite nouns as specific (even if they are ambiguous between a specific and a generic reading, e.g., I canguri hanno la coda, “The kangaroos have the tail”) and exhibit difficulties in rejecting bare nouns in generic contexts (that are not possible in Italian, e.g., *Patate crescono sotto terra, “Potatoes grow under the ground”). The heritage speakers in this study were raised with the OPOL strategy and, hence, are likely to have received consistent input at home during the first years of life. However, none of them attended HL classes (only two speakers were enrolled in a bachelor’s degree in Italian at the time of testing). This means that in this group, the second condition that we introduced in Section 1 for the successful acquisition of an HL, i.e., continuity of language exposure between home and school, was not met. This may account for the divergent behavior with respect to the phenomenon at hand5.

Based on the above review, we would once again like to point out the relevance of consistency and continuity in HL use for the acquisition of late-acquired phenomena, namely, those linguistic structures whose successful acquisition crucially depends on the amount of received input. As mentioned in Section 1, consistent use of the HL may play a more important role than exclusive use of it for successful HL acquisition. This certainly holds true for the successful acquisition of early phenomena, which are sensitive to age of onset rather than input quantity. For late or very late phenomena, the effects of consistency in language use may not be visible in the short term (i.e., if one focuses on a certain age span, as done in all studies reviewed in this section). However, in the long run, continuity and consistency of language use may be relevant for the acquisition of late and very late phenomena, too. In other terms, speakers whose use of the HL is consistent and continuous throughout the years may catch up with their monolingual peers who speak only Italian at home. Most of the speakers considered in this review were exposed to both the HL and the majority language from birth. Matching the results of studies related to school-age children (who may not master a linguistic phenomenon fully) with the ones concerning adults (who may exhibit successful acquisition of the phenomenon at stake) provides some preliminary evidence in favor of this hypothesis, as has been proposed in the present section. Furthermore, previous studies suggest that the acquisition of different phenomena may be more or less sensitive to consistency and continuity.

5. Concluding Remarks

Throughout the literature, many factors have been considered to account for the variation exhibited by HL speakers in their language acquisition outcomes. In this contribution, we focused on the notions of consistency and continuity of language experience across different contexts (home and school) over time.

Consistency implies using the same strategy of home language use over the years (from birth to current age). We speculated that for successful acquisition of an HL, consistency in language experience may be more relevant than the quantity of input in the HL itself. This complies with the observation that the acquisition of certain linguistic phenomena does not require much input (e.g., early-acquired phenomena in Section 4), which was made in previous studies. As for the acquisition of phenomena that are more sensitive to the quantity of exposure in the target language (i.e., late phenomena in Section 4), it is not possible to determine how much input is necessary for these phenomena to be acquired (see the discussion in Putnam and Sánchez 2013). It seems likely that even in a speaker’s less dominant language, cumulative input throughout the lifespan is enough for the successful acquisition of these phenomena. Indeed, the literature reports several examples of the successful acquisition of late phenomena even by heritage speakers who were exposed to both the HL and the majority language from birth, as was discussed in Section 4. Likewise, the questionnaire analysis discussed in Section 3 suggests that the children that experienced fewer switches in home language use tended to perceive themselves as more confident in the use of the HL.

We also proposed that continuity of language use between home and school plays a significant role in HL acquisition along with consistency in language use. This observation is in line with the idea (often discussed in the literature) that HL acquisition benefits from exposure to formal education in the target language (Section 1). Once again, the extent to which children were continuously exposed to education in the HL throughout the lifespan may be a better predictor of HL speakers’ acquisition outcomes than the quantity of exposure in the HL.

Therefore, we believe that the next research on HL acquisition should consider the notions of consistency and continuity in a child’s language experience as crucial in shaping HL acquisition outcomes. In this respect, the analysis of extensive longitudinal data looking at shifting/maintenance of language-use practices over time and their effect on heritage speakers’ language outcomes may be crucial.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this paper and are listed in alphabetic order. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Part of this research was funded by the Collaborative Center CRC 1252 “Prominence in Language” (research project “Reference management in bilingual narratives,” PIs: Christiane Bongartz and Jacopo Torregrossa).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, since this is a review study that discusses and reanalyzes data, which have been previously published.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the reviewed studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study may be made available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the schools for their support, the children for their enthusiasm in taking part in the study, and their parents for the great collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Antonijevic, Stanislava, Sarah Ann Muckley, and Nicole Müller. 2019. The role of consistency in use of morphosyntactic forms in child-directed speech in the acquisition of Irish, a minority language undergoing rapid language change. Journal of Child Language 47: 267–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, Adriana, Elisa Bennati, and Antonella Sorace. 2007. Theoretical and developmental issues in the syntax of subjects: Evidence from near-native Italian. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 657–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongartz, Christiane, and Jacopo Torregrossa. 2020. The effects of balanced biliteracy on Greek-German bilingual children’s secondary discourse ability. Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23: 948–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers-Heinlein, Krista. 2013. Parental language mixing: Its measurement and the relation of mixed input to young bilingual children’s vocabulary size. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 16: 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloi, Irene, Adriana Belletti, and Cecilia Poletto. 2018. Multilingual competence influences answering strategies in Italian–German speakers. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantone, Katja Francesca. 2005. Evidence against a third grammar: Code-switching in Italian–German bilingual children. In ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism. Somerville: Cascadillas, pp. 477–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cantone, Katja Francesca. 2007. Code-Switching in Bilingual Children. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cantone, Katja Francesca. 2020. Italienischstämmige SchülerInnen im Fremdsprachenunterricht Italienisch: Spracherwerb und Spracherhalt im mehrsprachigkeitsdidaktischen Kontext. In Mehrsprachigkeit im Fremdsprachenunterricht. Neue Studien und Konzepte zur Vernetzung von Schulsprachen und Herkunftssprachen. Edited by García Marta, Manfred Prinz and Daniel Reimann. Tübingen: Narr Verlag, pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonara, Valentina, and Andrea Scibetta. 2020. Integrating translanguaging pedagogy into Italian primary schools: Implications for language practices and children’s empowerment. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2010. The acquisition of adjectival ordering in Italian. In Variation in the Input. Edited by Anderssen Merete, Kristine Bentzen and Marit Westergaard. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chondrogianni, Vasiliki, and Theodoros Marinis. 2011. Differential effects of internal and external factors on the development of vocabulary, tense morphology and morpho-syntax in successive bilingual children. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 318–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Jim. 1979. Cognitive/academic language proficiency, linguistic interdependence, the optimum age question and some other matters. Working Papers in Bilingualism 19: 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 2019. The emergence of translanguaging pedagogy: A dialogue between theory and practice. Journal of Multilingual Education Research 9: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim, and Robin Persad. 2014. Teaching through a multilingual lens: The evolution of EAL policy and practice in Canada. Education Matters: The Journal of Teaching and Learning 2: 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Daskalaki, Evangelia, Vasiliki Chondrogianni, Elma Blom, Froso Argyri, and Johanne Paradis. 2019. Input effects across domains: The case of Greek subjects in child heritage language. Second Language Research 35: 421–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bree, Elisa, Josje Verhagen, Annemarie Kerkhoff, Willemijn Doedens, and Sharon Unsworth. 2017. Language learning from inconsistent input: Bilingual and monolingual toddlers compared. Infant and Child Development 26: e1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, Annik. 2007. Parental language input patterns and children’s bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics 28: 411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destatis, Statistisches Bundesamt. 2019. Bildung und Kultur. Allgemeinbildende Schulen. Schuljahr 2018/2019. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Schulen/Publikationen/Downloads-Schulen/allgemeinbildende-schulen-2110100197004.html (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Destatis, Statistisches Bundesamt. 2020. Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit: Ausländsiche Bevölkerung Ergebnisse des Ausländerzentralresigsters. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Publikationen/Downloads-Migration/auslaend-bevoelkerung-2010200197004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Di Venanzio, Laura, Katrin Schmitz, and Anna-Lena Scherger. 2016. Objects of transitive verbs in Italian as a heritage language in contact with German. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 6: 227–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döpke, Suzanne. 1992. One Parent One Language: An Interactional Approach. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler, Nadine, Veronika Jansen, and Natascha Müller. 2012. Gender acquisition in bilingual children: French-German, Italian-German, Spanish-German and Italian-French. International Journal of Bilingualism 17: 550–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Norbert. 2012. Bilingual Competence and Bilingual Proficiency in Child Development. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli, Domenico. 2016. La Nuova Immigrazione Degli Italiani in Germania. Available online: https://www.altreitalie.it/nuove_mobilita/dati_e_statistiche/istat/la-nuova-immigrazione-degli-italiani-in-germania.kl (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- García, Ofelia. 2009. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Li Wei. 2014. Language, bilingualism and education. In Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Carol Scheffner, Megan Dunn Davison, Frank R. Lawrence, and Adele W. Miccio. 2009. The effect of maternal language on bilingual children’s vocabulary and emergent literacy development during Head Start and kindergarten. Scientific Studies of Reading 13: 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istat. 2018. Mobilità Interna e Migrazioni Internazionali Della Popolazione Residente. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2018/12/Report-Migrazioni-Anno-2017.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Juan-Garau, Maria, and Carmen Pérez-Vidal. 2001. Mixing and pragmatic parental strategies in early bilingual acquisition. Journal of Child Language 28: 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasuya, Hiroko. 1998. Determinants of language choice in bilingual children: The role of input. The International Journal of Bilingualism 2: 327–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouritzin, Sandra G. 2000. A mother’s tongue. TESOL Quarterly 34: 311–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2007. Determiners in bilingual German-Italian children: What they tell us about the relation between language influence and language dominance. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 10: 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2012. Specific and generic subjects in the Italian of German-Italian simultaneous bilinguals and L2 learners. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 736–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2014. Adjective placement in simultaneous bilinguals (German-Italian) and the concept of cross-linguistic overcorrection. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 17: 222–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Cristina Pierantozzi. 2010. Interpreting definite plural subjects: A comparison of German and Italian monolingual and bilingual children. In 34th Boston University Conference on Language Development. Somerville: Cascadillas, pp. 245–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Jason Rothman. 2018. Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 564–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, Natascha Müller, and Katja Francesca Cantone. 2002. Gender in monolingual and bilingual first language acquisition: Comparing Italian and French. Lingue e Linguaggio 1: 107–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, Dagmar Barton, Katja Hailer, Ilse Stangen, Tatjana Lein, and Joost van de Weijer. 2014a. Foreign accent in adult simultaneous bilinguals. Heritage Language Journal 11: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, Tatjana Lein, Dagmar Barton, Dawn Judith Schröder, Ilse Stangen, and Antje Stoehr. 2014b. Acquisition outcomes across domains in adult simultaneous bilinguals with French as weaker and stronger language. Journal of French Language Studies 24: 347–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, Elizabeth. 1997. Language Mixing in Infant Bilingualism: A Sociolinguistic Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Feng. 2018. Parental Perceptions toward and Practices of Heritage Language Maintenance: Focusing on the United States and Canada. International Journal of Language Studies 12: 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Listanti, Andrea, and Jacopo Torregrossa. 2021. The acquisition of post-verbal subjects in heritage Italian: How timing of L1-acquisition modulates the acquisition of syntax-discourse interface structures. Paper presented at the RUEG Conference—Dynamics of Language Contact, Berlin, Germany, February 24. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Smith, Anika, Marieke Einfeldt, and Tanja Kupisch. 2020. Italian-German bilinguals: The effects of heritage language use on accent in early-acquired languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 24: 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Karen, and Alison Eisel Hendricks. 2014. What impact does ambiguous input have on bilingual language acquisition? Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 4: 363–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina-Mori, Satomi. 2011. A longitudinal analysis of language choice in bilingual children: The role of parental input and interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 3122–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Natascha, and Aafke Hulk. 2001. Crosslinguistic influence in bilingual language acquisition: Italian and French as recipient languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 4: 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Barbara A. 1995. Code negotiation in bilingual families: ‘My body starts speaking English’. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 16: 315–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne, and Samuel Navarro. 2003. Subject realization and crosslinguistic interference in the bilingual acquisition of Spanish and English: What is the role of the input? Journal of Child Language 30: 371–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichler, Edith. 1997. Migration und ethnische Ökonomie: Das italienische Gewerbe in Berlin. In Zuwanderung und Stadtentwicklung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 106–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, Edith. 2019. 9 Lifestyles, milieu languages and the economy: The presence of Italian in the urban spaces of Berlin. The Sociolinguistic Economy of Berlin: Cosmopolitan Perspectives on Language, Diversity and Social Space 17: 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzuto, Elena, and Maria Cristina Caselli. 1992. The acquisition of Italian morphology: Implications for models of language development. Journal of Child Language 19: 491–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Place, Silvia, and Erika Hoff. 2011. Properties of dual language exposure that influence 2-year-olds’ bilingual proficiency. Child Development 82: 1834–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Olga Kagan. 2007. Heritage languages: In the ‘wild’ and in the classroom. Language and Linguistics Compass 1: 368–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael T., and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. What’s so incomplete about incomplete acquisition?: A prolegomenon to modeling heritage language grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 478–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Jason. 2009. Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Marc. 2014. Italienische Migration Nach Deutschland: Soziohistorischer Hintergrund und Situation im Bildungssystem. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, Katrin, and Natascha Müller. 2008. Strong and clitic pronouns in monolingual and bilingual acquisition of French and Italian. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 11: 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, Katrin, Marisa Patuto, and Natascha Müller. 2011. The null-subject parameter at the interface between syntax and pragmatics: Evidence from bilingual German-Italian, German-French and Italian-French children. First Language 32: 205–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, Katrin, Laura Di Venanzio, and Anna-Lena Scherger. 2016. Null and overt subjects in Italian and Spanish heritage speakers in Germany. Lingua 180: 101–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]