Abstract

This study deals with the expression of additive linking in L2 French by adult German learners with two proficiency levels (advanced vs. intermediate). We examine whether crosslinguistic influences are observed in three domains: the frequency and type of additive expressions in discourse, the syntactic integration of additive particles in the utterance and the prosodic contour associated with them. A total of 70 participants (20 French native speakers, 20 German native speakers and 30 German learners of L2 French) performed an oral narrative task elicited via a video clip presenting abundant additive contexts. Our results show that advanced German learners did not experience an L1 transfer in any of the domains analyzed, but instead they show a learner-specific tendency to overmark the contrastive status of the relevant entities in discourse. Yet traces of crosslinguistic influence are visible in intermediate learners’ choice and frequency of additive means, as well as the preferred position of the particles. All learners seem to have quickly discarded the possibility to mark scope by prosody, in contrast to what they do in their L1. We discuss these findings in the light of the L2 acquisition of cohesive devices in discourse and their interactions with different linguistic levels.

1. Introduction

Learning to express addition in another language might seem relatively easy. An utterance such as “me too” as a reaction to someone else saying “I’d like a beer” is not very complicated, once you have identified the additive function of “too”. The task becomes somewhat more complex, however, when the utterance contains an explicit verb and you have to choose the additive particle to be used (too, as well or also) as well as its appropriate place in the utterance. It is then even more complex if you want to adhere to native speakers’ preferences in such choices, which also include the option of expressing a relation of similarity (for example, so do I) instead of an additive one.

These are the acquisitional aspects that we deal with in this article, which reports the results of an empirical study on the expression of additive relations in narrative discourse by adult German learners of L2 French. The languages in contact express such relations by similar means, the most common being particles such as Ge. auch and Fr. aussi, but differ, however, with respect to their syntactic embedding in the utterance and the way their semantic influence is signaled. In particular, German combines positional and intonational features to identify the constituent affected by a particle. For example, the context illustrated in (1) offers two options for the integration of Ge. auch: either the particle precedes the subject, which receives a pitch accent, or auch is placed after the finite verb and a pitch accent falls on the particle (1a). For the equivalent sentence in French, aussi can be inserted in different syntactic positions (although always after the added constituent, i.e., Marie), but prosody does not seem to play a specific role: the semantic scope of this particle can, however, be signaled by a pronoun copy of the subject (1b).

| 1. | Context: John speaks English |

| a. | auch MaRIe spricht Englisch/Marie spricht AUCH Englisch |

| b. | Marie aussi parle anglais/Marie parle (elle) aussi anglais/Marie parle anglais (elle) aussi |

Moreover, additive particles play an important role in information structure and discourse organization. In (1a, 1b), as replies to “John speaks English”, their presence signals which information unit is new and added to a previous assertion (in this case, the entity Marie), thereby ruling out the interpretation of the current sentence as a correction of preceding information. In stretches of connected discourse, additive particles thus establish an anaphoric link with respect to a previous utterance, containing the antecedent which satisfies their additive presupposition (in this case, someone else speaking English). In doing so, they contribute to enhancing discourse cohesion via interclausal relations of an additive nature (in other words “additive linking”). On this point, crosslinguistic comparisons (Dimroth et al. 2010, among others) highlight further differences between German and French concerning additive linking in discourse: German speakers abundantly use auch as a device to enhance discourse cohesion, whereas in similar contexts, aussi is much less frequent in French, as speakers tend to resort to other additive means or to establish another type of relation (such as so does she in relation to 1). The acquisition of additive linking in French L2 by German learners implies, therefore, a complex task which concerns the choice of the interclausal relation to be expressed for discourse cohesion (different possible relations), the selection of linguistic means to mark addition, the way additive items are integrated into the utterance and how their semantic influence is signaled (syntax vs. prosody).

Additive particles emerge early in adult L2 varieties, although learners take a long time to acquire the scope grammar of the target language (henceforth TL). For the advanced stages, it is not clear to what extent they manage to adopt native preferences (particle frequency, distribution and type of addition) and, if not, whether they are influenced by their L1 principles of discourse construction or by learner-specific tendencies (cf. Section 2.2). The interaction between syntactic development and the acquisition of intonation patterns related to such particles is a dimension that has not been sufficiently addressed in L2 studies. Previous research on German and Italian L2 (Andorno and Turco 2015) suggests that learners acquire the TL distribution of additive particles before their prosodic features, but there is no specific study on L2 French aussi.

In order to gain insight on the acquisition of additive means, we study additive linking in oral narratives produced in French L2 by German learners representing two proficiency levels (intermediate and advanced), in comparison to control groups of French and German native speakers. All participants produced narratives based on a visual stimulus (the Finite Story) which presents numerous additive contexts. Given the typological contrasts between French and German, we investigate three dimensions of L2 oral production: the frequency and type of additive expressions in discourse, the syntactic integration of additive particles in the utterance and the prosodic contour associated with them.

The article is organized as follows: In Section 2, we detail the main differences between the expression of additive linking in French and German as well as the results of previous studies on its L2 acquisition, before turning to the data and the methodology of our study (Section 3). Thereafter, we present the results of the study (Section 4), which are followed by their discussion (Section 5).

2. Additive Linking and L2 Acquisition: Background and Research Questions

2.1. Additive Linking in German and French

In the two languages under study, additive linking is mainly expressed by particles, respectively Ge. auch/ebenfalls/sogar and Fr. aussi/également/non plus/même, i.e., invariable items sharing a similar semantic meaning and structural properties (cf. König 1991; Gast and van der Auwera 2011; Nølke 1983)1. The particle selects part of the sentence it occurs in (its domain of application, i.e., the subject in ex.2) and states that the proposition holds for the affected constituent and at least one alternative element (in this case, another entity).

| 2. | a. | auch [Maria] spricht Englisch |

| b. | [Marie] aussi parle anglais |

Contrary to Ge. auch, Fr. aussi is replaced by non plus in negative contexts (Marie ne parle pas non plus anglais, “Mary does not speak English either”). In the following, we will focus on the differences between the central particles auch/aussi.

These items can occupy different positions in a sentence, which are language-specific. In a simple sentence with an SVO linear order where the particle semantically affects the subject, auch can precede it or follow the finite verb, whereas aussi can be placed after the subject, after the finite verb or after the complement.

The particle’s mobility contributes to the identification of the affected constituent. However, some placements might be ambiguous, as they are compatible with different interpretations of the particle scope (so-called wide-scope positions, cf. König 1991). This is the case when auch and aussi are placed after the finite verb, as in (3a, 3b), but also when aussi is at the end of the utterance (3c): from these positions, the particle can select any constituent of the utterance as the domain of application of its additive meaning.

| 3. | a. | [Maria] [spricht] auch [Englisch] |

| b. | [Marie] [parle] aussi [anglais] | |

| c. | [Marie] [parle] [anglais] aussi |

Even if the context usually allows the right interpretation, there are also language-specific devices to signal the particle’s scope. As was shown in (1), German makes use of prosodic cues to indicate whether the domain of application is on the right or on the left of the particle, whereas French can resort to syntactic means, at least when the addition affects the subject, with the insertion of strong pronouns referring anaphorically to it (Marie parle elle aussi anglais).

In this respect, languages with lexical stress such as German exploit pitch accents as an indication of pragmatic or discourse meaning in a more complex way than languages without lexical stress such as French. German pitch accents in prenuclear positions can display different melodic realizations such that many linguistic contrasts can be retrieved from prosodic realization only (Braun 2006). In contrast, French accented syllables in non-final positions are in most cases prosodically invariable, and the linguistic contrasts they convey (such as contrastive topic or contrastive narrow focus) are more restricted (Delais-Roussarie et al. 2015).

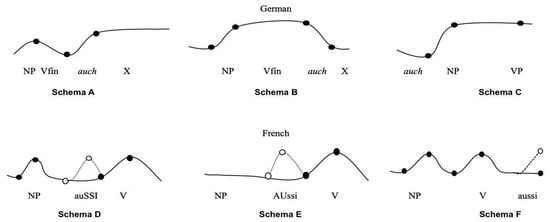

This difference also concerns the prosody of additive particles. According to Andorno and Turco (2015), if Ge. auch precedes the NP under its additive scope, as in the first option of (1a), the former is unaccented and the latter is produced with an important rising contour following a high plateau on the VP (schema C in Figure 1). If auch is embedded after the finite verb, as in the second option of (1a), two intonation patterns can be observed: (i) the additive particle is produced with a rising contour followed by a high plateau on the last constituent of the utterance (schema A in Figure 1) or (ii) a rising contour is produced on the NP followed by a high plateau on the finite verb and a falling movement on the additive particle (the “hat contour” represented in schema B in Figure 1)2. These patterns show that prosody plays an important role for the interpretation of auch.

Figure 1.

Pitch stylizations of GE. auch and Fr. aussi according to different syntactic positions.

Unlike German, the association between the particle aussi and the constituents under its scope is not clearly marked by prosodic cues in French. According to Benazzo and Patin (2017), an accented syllable (final or initial) realized on the particle aussi is not obligatory for its semantic interpretation (see the white dots in schemas D and E in Figure 1). Moreover, since both initial and final accents in prenuclear positions are mainly produced with a rising/high contour such as other prenuclear accents, authors argue that the scope of the particle aussi is mainly encoded by its position in the sentence or by other syntactic mechanisms (i.e., pronoun copies) but not by a particular melodic configuration. Hence, the particle aussi, as with many other lexical items, can bear or not an initial/final accent in order to mark the edges of the so-called groupe accentuel (Di Cristo 2016). When aussi is produced in sentence final position, a final falling contour is produced in conclusive statements, whereas a final rising contour is often produced in the case of continuations (schema F in Figure 1) or neutral yes–no questions.

Besides such grammatical asymmetries at the sentence level, GE. auch and Fr. aussi also differ in their frequency of use in discourse. Previous research, based on comparable data in German and French, has invariably attested that auch is much more frequent than aussi both in written texts (Blumenthal 1985; De Cesare 2015) and oral discourse (Dimroth et al. 2010; Benazzo and Dimroth 2015). This asymmetry has been related to language-specific choices among alternative discourse perspectives and cohesive means, which are typologically motivated. In particular, the analysis of data obtained with the same stimulus (Dimroth et al. 2010) shows that, for the additive contexts, French native speakers quite often mark a relation of similarity instead of addition, whereas German native speakers adhere massively to the additive perspective3.

2.2. L2 Acquisition of Additive Linking

Adult learners produce additive particles from the earliest stages of L2 acquisition (Dimroth 2002; Perdue et al. 2002, among others). For utterance embedding, the initial stages seem to be driven by the tendency to place particles adjacent to the constituent they affect (semantic transparency) and/or to adopt the most salient position in the input. In French L2, aussi is thus initially placed at the periphery of the verbal utterance (especially in the final position, or in the preverbal one), whereas the utterance-internal placement after the finite verb appears later, with the development of functional verb morphology (cf. Perdue et al. 2002). The use of contrastive pronouns is generally considered a late acquisition, typical of advanced learners (Benazzo et al. 2004).

Studies on intermediate levels reveal a certain impact of crosslinguistic influence on the distribution of additive particles. For example, intermediate Italian learners of French L2 realize a wider range of positions than same-level Russian learners and use the option of pronoun doubling earlier (Benazzo and Paykin 2017); German learners of French (Thörle 2020) and French learners of German (Bonvin and Dimroth 2016) exploit more frequently than TL native speakers the placement after the finite verb, which is common between the two languages. In both cases, however, the occurrence of L1 positions that do not correspond to a formally equivalent TL placement is rather sporadic. Such asymmetries seem to reflect Andersen’s (1983) principle “transfer to somewhere” and confirm Ringbom and Jarvis’s assumption that “learners are constantly looking for similarities (when they can find them) rather than for differences” (Ringbom and Jarvis 2009, p. 106).

Besides L1 effects, Thörle (2020) also attests an overuse of the preverbal position for aussi, which does not correspond to a possible placement in German. The high frequency of this position is put on a par with the abundance of left dislocations for entity reference in additive L2 utterances: considering these phenomena together leads the author to conclude that the preverbal position, be it combined or not with left dislocation, is a means to (over-)mark the information status of the entities, which are contrastive topics.

As for the type of relation, studies based on retellings of the Finite Story have highlighted learners’ tendency to reproduce in L2 the proportion of the two relations attested in their L1: thus, intermediate French learners of German (Bonvin and Dimroth 2016) overmark similarity in comparison to TL native speakers, whereas intermediate Italian learners of French overmark addition (Benazzo and Paykin 2017). In both studies, advanced learners come close to the target. Note that these results hold for the additive contexts, whereas for the contrastive ones of the same stimulus, even advanced learners do not match native preferences concerning the linguistic means put to use (Bonvin and Dimroth 2016; Benazzo et al. 2012). More generally, the adoption of the TL discourse perspective is considered to be a late acquisition for the expression of different domains (time/subject reference/space, etc.): on the one hand, taking a perspective implies that alternative means are available in L2 and, on the other, it is just a question of preferential choices among different options which are possible in the TL.

While the above-mentioned studies have investigated additive relations in L2 oral discourse, little is known about the interaction of syntactic development and the production of intonation patterns of additive particles. Andorno and Turco (2015) analyzed this aspect in the data of intermediate learners of two language pairs (L1 Italian > L2 German and vice versa). In these two languages, prosody has a function for the interpretation of additive particles, in addition to syntactic placement. The authors report that the acquisition of TL-like positional patterns precedes the acquisition of the prosodic ones. This is true for the postfinite position in L2 German, for which Italian learners fail to accent the particle in order to disambiguate its scope, as already observed in Becker and Dietrich (1996) for untutored beginners. However, this is also true for the adjacent initial position in Italian: German learners adopt this position, but they fail to deaccent the particle. In the present study, we also address this question. We examine to what extent learners whose L1 encodes additive linking via intonation patterns (German) learn not to use them when acquiring a target language like French, where the same function is mainly conveyed by syntactic mechanisms.

2.3. Research Questions

From the point of view of L2 acquisition, the study of additive linking is particularly interesting because of its complexity: learners have to choose simultaneously among different options at different levels. In the light of previous research, our study on German L1–French L2 learners deals with the following question: to what extent do learners adopt native French preferences for additive linking?

This general question can be split into more specific ones: (a) Which type of relation (additive/similarity) do learners mark to enhance discourse cohesion and by which means? (b) How do they embed additive particles in the utterance? (c) Does prosody contribute to scope marking as in their L1?

Given the typological contrasts between German and French, we investigate the role of crosslinguistic influence vs. learner-specific tendencies that could apply in L2 at any of the levels just mentioned. Taking into account both intermediate and advanced learners allows us to consider also a developmental dimension: can we attest an evolution in learners’ preferences according to their level?

3. Our Study: Method and Data

3.1. Objectives and Participants

The empirical data of our analysis are oral retellings elicited with a visual stimulus in L1/L2 French and L1 German. In order to study additive linking in L2, we first analyze how such relations are expressed by native speakers of French and German. This contrastive analysis aims at determining which means are more frequently used and how, both in the source and target languages. Then, we examine the expression of additive linking in German learners of French, who are divided in two groups according to their level in the target language (cf. Table 1).

Table 1.

The participants4.

All subjects are adults (aged between 20 and 48), with a comparable degree of education (university students or graduates), who have been recorded in the country of the TL, i.e., France for native speakers of French and L2 learners; Germany for native speakers of German.

None of the L2 subjects were exposed to French before age 10. The intermediates (henceforth INT) are mostly Erasmus students who, at the time of recording, had spent a few months but less than a year in France (mean length of residence = 4 months). Their proficiency level corresponds to B1/B2 of the Common European Framework of Reference5: their production shows the functional use of most common tenses (present, passé composé, imparfait) and some forms of subordination, but also the presence of grammatical errors (gender, agreement) and some uncertainty about the correct verb endings for less common lexical verbs.

The advanced learners (henceforth ADV) have been living and working in France for several years (mean stay: 6.5 years). Their level has been estimated on the basis of their oral production which is fluent and displays TL-like inflectional morphology and a high degree of syntactic complexity (various forms of implicit and explicit subordination). There are no grammatical errors in their production and their oral competence seems therefore to correspond to the C1/C2 level of the CEFR.

3.2. The Task: The Finite Story and Its Additive Contexts

The visual stimulus used to elicit oral production is the “Finite Story” video clip (cf. Dimroth 2006), which consists of 30 short segments showing the misadventure of three protagonists during a fire episode. The participants were asked to retell what happened in the story immediately after having watched each video segment.

This stimulus has been designed in order to obtain stretches of discourse with an information structure different from the prototypical one of narratives, in which the new information usually corresponds to the predicate. The additive contexts of the Finite Story correspond to video segments where the protagonists perform similar actions: the situation expressed by the predicate corresponds to given information (repeated similar actions), whereas the entities, which have been introduced from the first sequences, have a topical status but change from one utterance to the next (Dimroth et al. 2010).

The analysis is based on eight narrative sequences of this type, i.e., segments 4–5–8 (already analyzed in Dimroth et al. 2010) and segments 21–21–25–27–29, in which the additive relation concerns the subject entities. Table 2 reports the content of the video segments analyzed (in bold) as well as the relevant antecedent scene to which an additive link can be established.

Table 2.

The Finite Story: additive segments selected for analysis and relative antecedents.

Each of the selected segments is a favorable context encouraging the expression of an additive relation, as in (4a), where the additive particle highlights that a previous assertion holds for a different entity (anaphoric link in the domain of entities). However, it is equally possible to highlight the similarity of the situation by establishing an anaphoric link on the predicate domain, as in (4b), or leave out any specific additive marking, as in (4c).

| 4. | Previous context: Mr. Blue goes to bed | |

| a. | Mr. Green also goes to bed. | Addition of another entity |

| b. | Mr. Green does the same. | Similarity to a previous situation |

| c. | Mr. Green goes to bed. | No marking |

The choice between the two types of anaphoric relation, as in (4a, 4b), is actually possible when the repetition of similar situations takes place in two subsequent sequences. This is the case for all the selected contexts, except scene 29.

3.3. Procedure

The analysis of native and non-native productions proceeded in the following steps. First, we considered the means used to mark the additive contexts and their frequency. The proportion of markings was calculated by dividing the number of mentioned events which could possibly be marked for addition (allowing a comparison with a previous utterance of the same speaker) by the number of utterances that have actually been marked, either for the additive or similarity relation. All the narrative utterances showing a misinterpretation of the correspondent video segment were excluded from the analysis. Then, we calculated the percentage of markings for each of the two relations (addition vs. similarity) and the repertoire of the correspondent linguistic means.

Afterwards, we focused on the structural integration of additive particles inserted in utterances containing the entity as grammatical subject and a finite verb (exclusion of nominal elliptic ones, such as Mr. Red too). For these utterances, we considered the position of the additive particle with respect to the major constituents of the sentence (initial, preverbal, after the finite verb, etc.).

Finally, we analyzed the pitch contours of additive utterances with the particle aussi in L2 French. In order to verify the presence of specific melodic movements triggered by German L1, we examined whether the final/initial vowels of aussi are produced with any melodic movement (falling, rising or dynamic) with a glissando threshold of 0.32/T2 via the Prosogram tool (Mertens 2014). Pitch contours were manually labeled by one of the authors (an experienced phonetician) according to ToBI labels for French (Delais-Roussarie et al. 2015). Note that this part of the study is rather qualitative: the prosodic analyses could not be conducted on the whole dataset, since most recordings suffer from poor acoustic quality.

4. Results

The results for native and non-native productions are presented in the following order: first, we consider the frequency of additive linking for the contexts analyzed and the relevant means used for doing so (Section 4.1), then the utterance embedding of additive particles (Section 4.2) and, finally, the prosodic contour associated with their use in L2 (Section 4.3).

4.1. Additive Linking: Means and Frequency

The quantifications of native speakers’ data (cf. Table 3) show a higher percentage of marked utterances in the German retellings (61.60%) in comparison with the French ones (43.40%). A chi-square test confirms that this difference is statistically significant (χ2 = 4.43, p < 0.03).

Table 3.

Proportion of marked utterances in native productions.

Concerning the proportion between the two possible relations (addition vs. similarity), additive markings represent the majority in both languages: they are, however, much more frequent in German (92.75%) than in French (72.54%), where speakers opt quite often for the similarity relation (27.45 % in French vs. 7.24% in German). These data reconfirm German speakers’ stronger tendency to mark the additive relation in comparison to French speakers for this informational context.

The means used to mark addition are quite similar in both languages (cf. Table 4): they correspond mainly to the central additive particles Ge. auch (119 occurrences) and Fr. aussi (47 occurrences), followed by the more formal lexical variants Ge. ebenfalls (7 occurrences) and Fr. également6 (13 occurrences). In French, we also attest the presence of non plus (12 occurrences), the negative counterpart of aussi, whereas Ge. auch is also used in negative contexts. In addition, native speakers sporadically produce other expressions, such as “in its turn”/“it is his turn” (two occurrences of Fr. à son tour; one of Ge. dran sein) or again (one wieder).

Table 4.

Linguistic means used by native speakers in the additive contexts.

The similarity relation is also expressed by rather equivalent structures in the two languages: Fr. même (“same”), be it used in its adverbial (faire de même “do the same”) or adjectival function (même N “same N”), as in (5a-b), and Fr. pareil (“similarly”) correspond to Ge. selb/gleich (or dasselbe/das gleiche), as in (5c).

| 5. | a. | M. Vert fait de même (4-sbj3)7 |

| “Mr. Green does the same” | ||

| b. | M. Rouge a la même réaction (25-sbj 10) | |

| “Mr. Red has the same reaction” | ||

| c. | Herr Grün (…) hat auch n gleichen ängstlichen gesichtsausdruck wie herr blau (20-sbj 10) | |

| “Mr. Green (…) has also the same fearful facial expression as Mr. Blue” |

Such means are, however, attested with a different frequency: German speakers massively use auch (119 occurrences out of 138 markings = 86%), whereas French speakers resort to aussi in a more limited way (47 out of 102 markings = 46%), this item being occasionally replaced by its negative counterpart non plus or the more formal variant également for addition, or by the alternative expression of similarity.

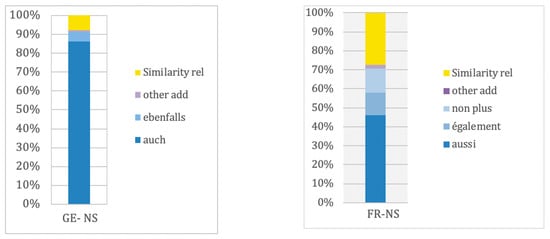

The proportion of each means is illustrated in Figure 2 where the colors are meant to facilitate the visualization of the functional correspondences between the two languages: additive means in different shades of blue and similarity means in shades of yellow.

Figure 2.

Proportion of additive means used by native speakers.

The comparison of native French and German additive linking allows us to characterize the L2 acquisitional task: once German learners have identified the correspondent means in French, in order to approach the TL they should modify the frequency for each type of marking. If learners tend to reproduce L1 patterns, we can expect that German learners of French L2 will: (a) produce a higher number of marked utterances in comparison to French native speakers; and (b) overmark the additive relation at the expense of the similarity relation.

The analysis of L2 French apparently confirms both hypotheses. Starting with the global proportion of marked utterances (Table 5), learners seem to overmark the additive contexts, but the INT group do it to a much higher extent (68.88%) than the ADV group (56.17%). In fact, only the difference between the INT group and French native speakers reaches significance (χ2 = 6.78, p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Proportion of marked utterances in French L2.

Both L2 groups produce, however, a similar amount of marked utterances in absolute numbers (93 vs. 91). What changes is the number of event mentions: ADV learners mention more events than the INT ones to describe the same additive scenes—cf. (6a) with just one event mention and (6b) with two—but it would be redundant to mark either addition or similarity for each additional event.

| 6. | a. | M.Rouge e: # aussi # ne veut pas sortir8 (25-GE-Int10) |

| “Mr. Red also does not want to go out” | ||

| b. | mais lui également il a peur/il refuse de sauter (25-GE-Adv02) | |

| “but him also he is afraid/he refuses to jump” |

The decrease attested in the retellings of the ADV group is therefore a consequence of their higher granularity. These learners still present a higher proportion of marked utterances when compared to French native productions, but this difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.31).

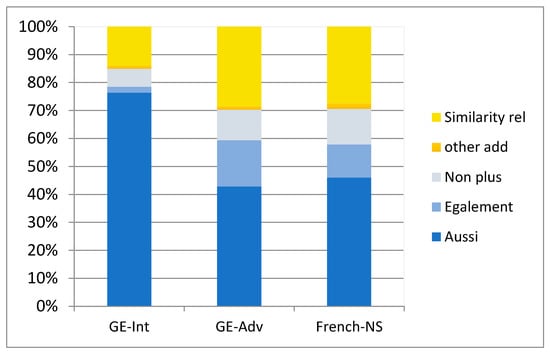

The intermediates’ overmarking clearly concerns addition (86.02%) with respect to similarity (13.97%), in proportions that are similar to what is attested in German L1. The ADV group shows an increase in similarity markings (28.57%) at the expense of the additive ones (71.42%): as a consequence, the type of relations they mark is very close to the ratio attested in the French native group.

Figure 3 illustrates this evolution with an overview on the means used at each level. For ease of comparison, we also report the data of the French control group.

Figure 3.

Proportion of means used in French L2 in the additive contexts.

The L2 INT group thus displays a massive use of the central particle aussi (71 occurrences/93 marks, i.e., 76.3% of all means), sporadically replaced by non plus (6 occurrences) and également (2 occurrences), whereas L2-ADV enlarge their use of the other additive means (39 aussi, 15 également, 10 non plus).

Although not detailed in Figure 3, an enrichment of the lexical repertoire is also attested for the similarity relation, which goes from the exclusive use of structures equivalent to same (same thing or same X) in INT to a more varied repertoire—pareil (likewise), suivre l’exemple (follow the example of X)—in ADV. As a result, the proportion and type of means mobilized by the ADV group for both relations are very similar to the native French control group.

4.2. Additive Particles: Structural Integration in the Utterance

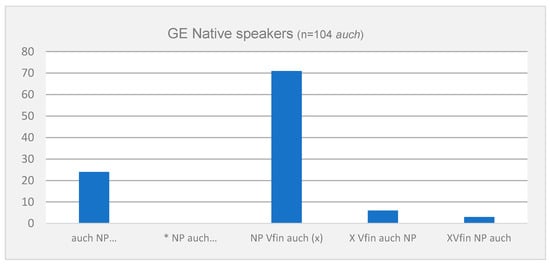

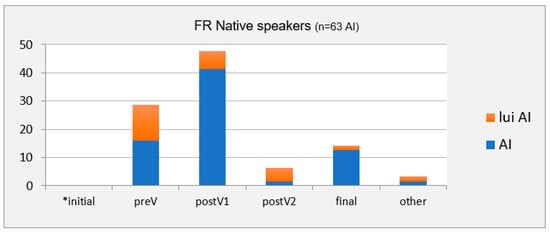

Before analyzing the L2 embedding of additive particles in the utterance, we consider their distribution in native productions. The relevant evidence for German is calculated on the basis of 104 occurrences of the particle auch in verbal utterances (cf. Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of additive auch in the utterance (* = agrammatical position in the TL).

As expected, auch is most frequently placed after the finite verb (71 occurrences), as in (7a). However, there is also a consistent number of occurrences (24 occurrences) where it immediately precedes the initial NP (7b).

| 7. | a. | Herr Grün ist AUCH aufgewacht (20-Sbj 21) |

| “Mr. Green also woke up” | ||

| b. | auch Herr GRÜN war nun wach und hatte angst (20-Sbj 22) | |

| “also Mr. Green was now awake and was scared” |

The remnant occurrences correspond to sentences with a linear order different from SVO. When the sentence starts with a non-subject constituent, the subject and the particle follow the finite verb: in this case, auch can be placed either before the subject (ex.8a) or after it, as in (8b).

| 8. | a. | jetzt ist auch Herr GRÜN in das sprungtuch gesprungen (27-Sbj 31) |

| “now has also Mr. Green in the security net jumped” | ||

| b. | jetzt springt Herr Rot AUCH aus dem Fenster (29-Sbj 35) | |

| “now jumps Mr. Red also out of the window” |

Turning to French, the relevant additive items are aussi, également and non plus (henceforth AI: additive items), which share in principle the same structural distribution (cf. Nølke 1983) as well as the option of pronoun reduplication when they are associated with the grammatical subject. The analysis is based on a total of 63 additive utterances with an explicit verb. The following examples (9a–d) illustrate each of the positions attested, which are quantified in Figure 5. Note that the position after the final verb may coincide with the utterance final one in the absence of a complement, as in (9b).

| 9. | Preverbal position |

| a. | M. Rouge aussi a peur (25-sbj 16) |

| “Mr. Red is also afraid” | |

| After the finite verb (PostV1) | |

| b. | M. Rouge refuse également (25-sbj2) |

| “Mr. Red refuses as well” | |

| after aux-Vlex (PostV2) | |

| c. | M. Vert a décidé lui aussi de sauter (27-sbj19) |

| “Mr. Green has decided him too to jump” | |

| Utterance final (= after the complement or a non-finite verb) | |

| d. | M. Rouge s’est réveillé également et commence à paniquer aussi (21-sbj1) |

| “Mr. Red also woke up and begins to panic as well” |

Figure 5.

Distribution of additive items “aussi”, “également” and “non plus” in the utterance. AI = additive item; lui AI = additive item with strong pronoun (* = agrammatical position in the TL).

As shown in Figure 5, the occurrences of AI spread over each of the possible positions: they are most frequently placed after the finite verb (41.2%), but there is also a consistent number of occurrences where the particle is in the preverbal position (28.5%), after the aux-V group (6.3%) and in the final position (14.2%). Pronoun doubling, attested with aussi and non plus, is produced in all positions for a total of 17 occurrences, which means roughly 27% of all AI occurrences.

The AI in the two languages share thus a common preferential position (post-Vfin), which is, however, highly dominant in German in comparison to French (around 70% vs. 40%). All other placements are language-specific: as for the area before the finite verb, the German particle is placed before the subject, whereas in French, it follows it, and for the final area, the utterance final position is possible in German when the particle is in a postfinite position of a sentence without a non-finite verb (e.g., Herr Rot schläft auch), whereas in French, it is quite common with SVO structures.

In addition, French speakers resort quite often to pronoun reduplication, which is attested in all syntactic positions, whereas a corresponding construction is not used in German.

If learners look for similarities, it is expected that they will overuse the common position after the finite verb, all other positions being rather different from those possible in their L1. The optionality of strong pronouns is instead a feature that might delay their acquisition.

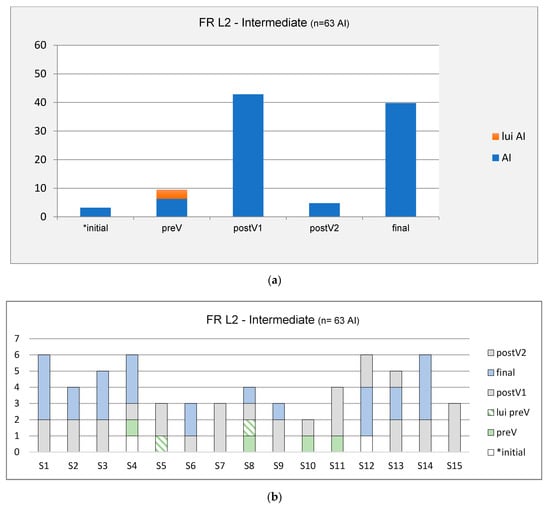

Starting with the INT group, their production presents a total of 63 AI inserted in verbal utterances (respectively, 59 aussi and 4 non plus). Their distribution is represented in Figure 6a for the whole group and then split individually in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

(a) Intermediate learners: group distribution of AI. (b) Intermediate learners: individual distribution of AI (* = agrammatical position in the TL).

As expected, AI are mainly placed after the finite verb (42.85%): this position is exploited by 14 learners. Two of them (S7 and S15) only use this placement, but most subjects exploit at least two different positions.

The utterance final one is the second most widespread (39.78%, produced by 10 learners): even if it does not correspond to an equivalent placement in German L1, this position is frequent in the input and perceptually salient.

The initial position, typical of the learners’ L1, is instead quite rare (two occurrences by two subjects).

Finally, the preverbal position is much less frequent (less than 10%) than the postfinite and final positions, but it is the only placement in which strong pronouns appear (two occurrences by two subjects).

| 10. | il ne dort plus et lui aussi il a peur (20-Ge-Int05) |

| “he is not sleeping anymore and him too he is afraid” |

The presence of strong pronouns associated with additive items is therefore relatively rare. It is, however, important to signal two more occurrences in which the pronouns are disjointed from the particle, the former being placed in the subject position and the particle after the finite verb (11a–b). For these structures, Figure 6a,b report only the position of aussi (respectively, after V1 and final).

| 11. | a. | et finalement lui il saute aussi (29-Ge-Int05) |

| “and finally him he jumps too” | ||

| b. | mais lui il a peur aussi (25-Ge-Int04) | |

| “but him he is afraid too” |

Given the unique position of strong pronouns, their sporadic use does not seem to function as a means for disambiguating the scope of additive items.

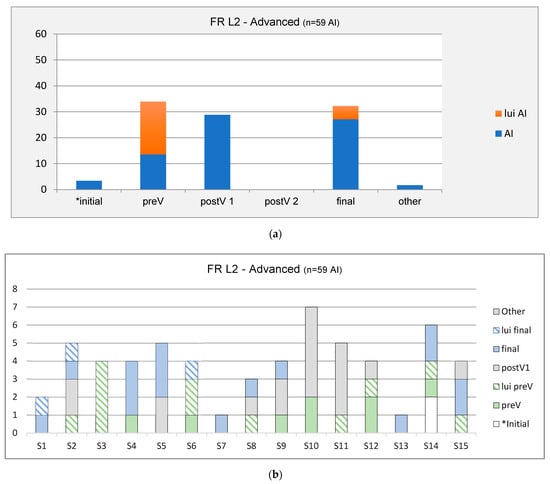

Turning to the ADV group, their productions include 59 AI (38 aussi, 12 également and 9 non plus) inserted in verbal utterances (cf. Figure 7a,b).

Figure 7.

(a) Advanced learners: Group distribution of AI. AI = 38 aussi, 12 également, 9 non plus. (b) Advanced learners: individual distribution of AI (* = agrammatical position in the TL).

Compared to the INT group, advanced learners show an increasing proportion of the preverbal position (11 subjects; the only position for one of them) and of the final position (11 subjects; the only position for 2 of them), at the expense of the position after Vfin (7 subjects): as a result, the three main positions are almost used to the same extent (with a slight preference for the preverbal one) and with all three AI.

The presence of strong pronouns also increased9 (15 occurrences for a total of 25.4%, produced by 9 subjects), thus reaching native French proportions.

| 12. | a. | mais lui non plus veut pas sauter (25-Ge-Adv11) |

| “but him neither wants to jump” | ||

| b. | mais lui également il a peur (25-Ge-Adv02) | |

| “but him also he is afraid” | ||

| c. | au final lui aussi il se jette par la fenêtre (29-Ge-Adv08) | |

| “in the end him too he throws himself through the window” |

However, most of them are still associated with the preverbal position, which is the clearest in terms of scope, and quite often accompanied by left dislocations, as in (12bc).

Finally, the incorrect initial position is still attested, but only in one subject (S14) and only with aussi.

With the exception of such occurrences, the distribution of additive particles in ADV learners is, on the whole, rather close to French native preferences. The only feature distinguishing the L2 production seems to be the absence of pronoun doubling in the position after the finite verb.

The frequent presence of dislocated structures (such as Mr. Rouge, il … or lui aussi il …) is, however, intriguing. In the light of previous research, we therefore explore Thörle’s hypothesis about German learners’ tendency to overmark contrastive topics in additive utterances. For this purpose, we take into account both the presence of strong pronouns and of left dislocations, which is another means to highlight the contrastive status of the subject. Table 6 reports the examples of utterances that will be considered as unmarked vs. marked for contrastive topics and the possible position of the AI.

Table 6.

Marked expressions of contrastive topics in additive utterances.

Note that left dislocations are not attested in the additive utterances in German L1, nor the presence of pronoun doubling, although highlighting of the subject is in principle possible, as in (13).

| 13. | Herr Blau, der hat das Feuer gesehen. |

| “Mr. Blue, he has seen the fire” |

As Table 7 shows, both groups of learners use left dislocations in additive utterances more often than French native speakers do. In particular, L2 ADV learners indeed overmark contrastive topics (almost 39%) in comparison to the French control group (28.5%), both with left dislocations and strong pronouns and by combining the two means, whereas INT do so to a much lesser extent (14.2%), and they do it more frequently with left dislocations. Given the absence of formally similar structures in German, the presence of such structures cannot be attributed to an L1 influence.

Table 7.

Marked expressions of contrastive topics in L1 and L2.

Although the number of occurrences is low, as we have considered just the additive sentences, it seems that learners try to signal the contrastive informational status of the entity first by left dislocations and later on with strong pronouns. In other words, the overmarking of contrastive topics seems to develop in the advanced stages, together with a more skillful use of different types of pronouns for reference to entities.

4.3. Additive Particles and Prosody: An Exploratory Analysis

Our final analysis consisted in examining pitch contours on the additive aussi (postfinite positions) and the NP under its scope produced by German learners with a qualitative approach (17 and 9 utterances by intermediate and advanced learners, respectively). Our goal was to verify whether an L1 prosodic transfer from German to L2 French was observed in this set of data. If this was the case, we expected to observe complex melodic contours on this particle as described in Figure 1 (schemes A and B): either aussi produced with a final pitch accent followed by a high plateau or with a falling one preceded by a high plateau.

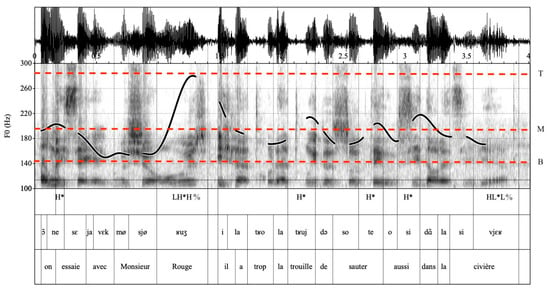

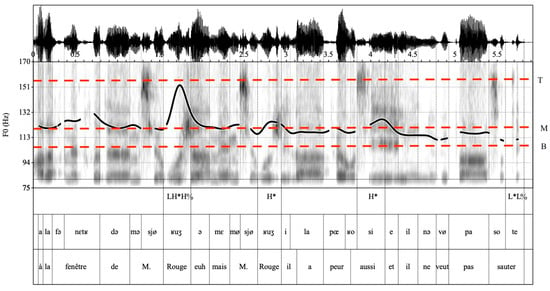

According to L1 French descriptions (Di Cristo 2016), the additive particle aussi, a lexical item, can be produced with both initial and final accented syllable markings at the edge of the groupe accentuel that it forms. Figure 8 illustrates the prototypical prosodic pattern of aussi in L1 French: a high pitch H* is observed on the last syllable of this word.

Figure 8.

Utterance produced by a French native speaker (25-Sbj01). Accented syllables are indicated with *.

Note that the peak of this melodic movement does not reach the speaker’s top range (T). The maximum of the rise is located at her mid-pitch range (M), similarly to other non-final accents associated with the words trouille and sauter. Since this rise does not display any complex melodic realization (such a rising–falling movement) or an initial accent with an important melodic realization, some scholars conclude that French speakers do not employ prosody in order to convey a semantic/discourse meaning to this particle (Benazzo and Patin 2017).

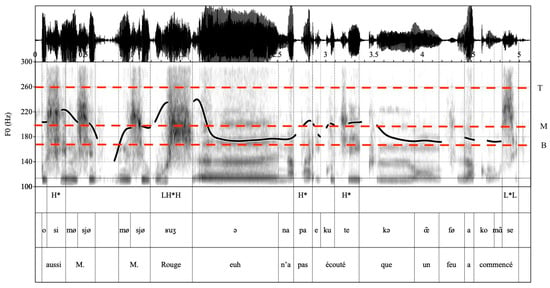

Examples in Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrate the melodic movements produced by German learners in L2 French. In Figure 9, the particle aussi is produced with a final rise H* on its last syllable. The peak of this rise does not reach the top of the speaker’s range (T).

Figure 9.

Additive utterance in French L2 with postfinite aussi (25-INT sbj01). Accented syllables are indicated with *.

Figure 10.

Additive utterance in French L2 with initial aussi (8-INT sbj 12). Accented syllables are indicated with *.

In our data, 22 out of 26 utterances were produced with this melodic pattern with an equal distribution across the two proficiency levels. Only in 8 out of 26 utterances did German learners not produce any accented syllable on this particle (3 for intermediates, 5 for advanced). In all the cases, complex melodic configurations were not observed, nor were initial accents on the particle aussi.

All in all, these qualitative analyses indicate that L2 melodic movements produced by German learners are not triggered by their L1. Rather, these patterns show that learners do not use prosody for marking the association between the particle aussi and the constituent under its scope. More interestingly, in two sentences displaying a similar syntactic structure of L1 German, such as the example in Figure 10 (initial aussi placed before the subject NP), intermediate learners did not produce a melodic configuration transferred from their L1: (i) aussi carries a final accented syllable, whereas in L1 German, this particle should be unaccented, and (ii) there is no high plateau covering the NP associated with this particle such as in German, but rather a prototypical final rising accent, the latter in accordance with French prosodic patterns. These examples suggest that in cases in which L1 transfer is observed at the syntactic level, learners do not transfer their L1 intonation patterns to the target language.

5. Summary and Discussion

In this study, we examined the expression of additive relations in French L2 by intermediate and advanced learners with L1 German. We considered three dimensions for which French and German differ.

(a) Concerning the type of additive linking, the analysis of our control groups reconfirms the stronger tendency of German speakers to mark addition in comparison to French speakers, as attested in previous research. Intermediate learners roughly reproduce their L1 patterns of discourse cohesion both for the frequency of the relation expressed (overmarking of the additive relation) and for the type of means employed (massive use of aussi). Advanced learners, instead, reach a repertoire of means and a proportion of markings which is very close to that attested in native French.

A similar development has also been reported in previous studies using the same stimulus (Bonvin and Dimroth 2016; Benazzo and Paykin 2017): the overmarking of the L1 preferred relation, typical of intermediates, fades away and advanced learners thus manage to adopt the TL discourse perspective for additive linking, although this is not the case for the contrastive contexts of the same stimulus (Bonvin and Dimroth 2016; Benazzo et al. 2012).

For this acquisitional dimension, it is clear that the L1 drives the choices of intermediates, but the results hint at another intriguing point, namely, what pushes learners to conform to TL native speakers, given that it is solely a question of “preferential” discourse perspective, as opposed to grammaticality: even if they continued to adhere to their L1 patterns, their production would actually not be considered incorrect nor would they be corrected. It begs the question whether such an acquisitional trend may reflect an effect of larger exposure to (native) input (length of stay in the TL country) or to natural progression in L2 (or a combination of both), in so far as these are the two conditions that distinguish our L2 groups.

(b) The analysis of the native speakers’ production also reconfirms the different distribution typical of French vs. German additive particles, which share just one common position.

The INT group already exploits all structural placements of the TL (plus the incorrect initial one), although there is not much variation at the individual level. On the whole, two positions are dominant: the frequency of the final position is probably a remnant of a previous stage, whereas the abundance of the postfinite placement is clearly due to an L1 influence. The incorrect initial position has, instead, already been discarded by the majority of the subjects. Similar results are also attested in Thörle (2020) for L1 German–L2 French and, in the opposite direction, in Bonvin and Dimroth (2016). On this point, it seems clear that learners look indeed for similarities in the input and, when they do not find them, abandon the L1 option.

In advanced learners, the three structural positions are almost equally used. In addition, these learners more frequently exploit the option of strong pronouns. Except for their placement, which is concentrated at the beginning of the utterance, advanced learners use additive particles very much like native speakers of French.

The use of strong pronouns in L2 (intermediate and advanced) is clearly not meant as a syntactic device to indicate which constituent is associated with the particle, as such pronouns are almost always produced in the preverbal position which admits only scope over the subject. Moreover, they can also be disjointed from the particle (intermediate level). A closer look at reference to entities in native and L2 additive utterances reveals, however, that the ADV group overmarks contrastive topics, either by using strong pronouns or left dislocations for subject topicalization.

The latter result partially confirm Thörle’s (2020) remarks on L1 German–L2 French about an L2 tendency to overmark the contrastive status of entities. The group she considers includes learners at the B1/B2-C1 levels. Having separately considered two levels of proficiency, we can add a developmental dimension: specific means to mark contrastive topics are already used at the intermediate level (B1/B2 level), but the overmarking effect is only attested in advanced learners (C1/C2), i.e., once learners have acquired more diversified means for entity reference in L2.

Such results recall the overexplicitness attested in L2 (independent of L1) for reference to entities in contexts of maintenance, such as the use of full NPs instead of pronouns (cf. Hendriks 2003, among others). Our analysis has been limited to additive utterances, in which entities often have the status of contrastive topics. In the future, it would be useful to study reference to entities also in non-contrastive contexts in order to verify if dislocations are indeed associated with a contrastive status of the entity or not.

(c) Concerning prosody, Andorno and Turco (2015) found that learning both syntactic and intonation patterns of the additive particles anche in L2 Italian and auch in L2 German is challenging for L1 German and L1 Italian learners, respectively. The authors claim that producing these particles in canonical positions in utterances is less problematic than producing intonational patterns in a native-like way. Differently from the previous study, our qualitative analyses show that producing TL prosodic patterns on the aussi particle is less problematic than other dimensions such as its embedding in canonical syntactic positions. We found that German learners do not use prosodic cues from their L1 for expressing additive relations in L2 French, independently of their proficiency level.

Our observations suggest that learners have quickly discarded the possibility to mark scope by prosody in L2 French, a language in which such a relation is not coded by intonation patterns. Learning not to use intonative markings when the L1 does (German L1–French L2) seems to be an easier acquisitional task than doing the opposite (L1 French–L2 German), especially given the systematic absence of such markings in French in general. This could be the explanation for the lack of L1 influence at the prosodic level already at the intermediate level, in comparison with the other dimensions analyzed, which imply instead taking into account statistical preferences (frequency of the additive vs. similarity relation), availability of different structural positions (embedding of additive particles) or multifunctional grammatical items (weak vs. strong pronouns).

It would, however, be interesting to investigate the role of prosody in French L2 at lower levels of proficiency, in order to determine whether this possibility is indeed used and when it is discarded.

6. Conclusions

The goal of our study was to determine to what extent German learners of French L2 manage to adopt native speakers’ preferences for additive linking and whether the L1 influenced any of the three dimensions considered. In doing so, we found that the ADV group is surprisingly close to the target at all levels analyzed: no traces of L1 influence have been detected, but rather a learner-specific tendency to overmark the contrastive status of the relevant entities in discourse.

Traces of crosslinguistic influence are instead visible in the INT group concerning their choice and frequency of additive means (relation to be marked and lexical type) as well as the preferred position of the particles with respect to the different options available in the TL. Learners seem, however, to have quickly discarded the possibility to mark scope by prosody, contrary to their L1, and to use L1 typical placements which are not allowed in French. On the whole, such results support the idea that learners are looking for similarities and avoid L1 options when they do not find them in the TL. In the case of prosody, the task seems to be easier than for the syntax–semantics dimension, as the French input does not encourage similarity at this level, whereas for the type of relation to be marked and the syntactic embedding of the particle, learners have to deal with preferential choices among different possible options.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.; methodology, formal analysis and investigation B.S., D.C. and F.S.; writing-original draft, B.S.; writing-review and editing, B.S., D.C. and F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (French data) or from Christine Dimroth (German data).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andersen, Roger. 1983. Transfer to Somewhere. In Language Transfer in Language Learning. Edited by Susan Gass and Larry Selinker. Rowley: Newbury House, pp. 177–201. [Google Scholar]

- Andorno, Cecilia, and Giuseppina Turco. 2015. Embedding additive particles in the sentence information structure: How L2 learners find their way through positional and prosodic patterns. Linguistik Online 71: 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Angelika, and Rainer Dietrich. 1996. The acquisition of scope in German. Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenchaft und Linguistik 104: 115–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzo, Sandra, and Christine Dimroth. 2015. Additive particles in Germanic & Romance languages: Are they really similar? Linguistik Online 71: 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Benazzo, Sandra, and Cédric Patin. 2017. French additive aussi: Does prosody matter? In Focus on Additivity. Adverbial Modifiers in Romance, Germanic and Slavic Languages. Edited by Anna Maria De Cesare and Cecilia Andorno. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 107–36. [Google Scholar]

- Benazzo, Sandra, and Katia Paykin. 2017. Additive relations in L2 French: Contrasting acquisitional trends of Italian and Russian learners. In Focus on Additivity. Adverbial Modifiers in Romance, Germanic and Slavic Languages. Edited by Anna Maria De Cesare and Cecilia Andorno. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 265–309. [Google Scholar]

- Benazzo, Sandra, Christine Dimroth, Clive Perdue, and Marzena Watorek. 2004. Le rôle des particules additives dans la construction de la cohésion discursive en langue maternelle et en langue étrangère. Langages 155: 76–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzo, Sandra, Cecilia Andorno, Grazia Interlandi, and Cédric Patin. 2012. Perspective discursive et influence translinguistique: Exprimer le contraste d’entité en français et en italien L2. Language, Interaction & Acquisition 3: 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, Peter. 1985. Aussi et Auch: Deux faux amis? Französisch Heute 2: 144–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bonvin, Audrey, and Christine Dimroth. 2016. Additive linking in L2 discourse: Lexical, syntactic and discourse organizational choices in Intermediate and Advanced learners of L2 German with L1 French. Discours 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Bettina. 2006. Phonetics and Phonology of Thematic Contrast in German. Language and Speech 49: 451–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cesare, Anna Maria. 2015. Additive focus adverbs in canonical word orders. A corpus-based study on It. anche, Fr. aussi and E. also in written texts. Linguistik Online 71: 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Delais-Roussarie, Elisabeth, Brechtje Post, Mathieu Avanzi, Carolin Buke, Albert Di Cristo, Ingo Feldhausen, Sun-Ah Jun, Philippe Martin, Trudel Meisenburg, Annie Rialland, and et al. 2015. Intonational phonology of French: Developing a ToBI system for French. In Intonation in Romance. Edited by Sonia Frota and Pilar Prieto. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 63–100. [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristo, Albert. 2016. Les Musiques du Français Parlé. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, Christine. 2002. Topics, Assertions, and Additive Words: How L2 Learners Get from Information Structure to Target-Language Syntax. Linguistics 40: 891–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimroth, Christine. 2006. The Finite Story. Max-Planck-Institute for Psycholinguistics. Available online: https://www.iris-database.org/iris/app/home/search;jsessionid=FEDEBE45A55A02D06249396FDB770E9E?query=Dimroth (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Dimroth, Christine, Cecilia Andorno, Sandra Benazzo, and Josje Verhagen. 2010. Given claims about new topics. How Romance and Germanic speakers link changed and maintained information in narrative discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 42: 3328–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, Volker, and Johan van der Auwera. 2011. Scalar Additive Operators in the Languages of Europe. Language 87: 2–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, Henriette. 2003. Using nouns for reference maintenance: A seeming contradiction in L2 discourse. In Typology and Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Anna Giacalone Ramat. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 291–326. [Google Scholar]

- König, Ekkehard. 1991. The Meaning of Focus Particles. A Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, Piet. 2014. Polytonia: A system for the automatic transcription of tonal aspects in speech corpora. Journal of Speech Sciences 4: 17–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nølke, Henning. 1983. Les Adverbes Paradigmatisants. Fonction et Analyse. Copenhague: Akademisk Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Perdue, Clive, Sandra Benazzo, and Patrizia Giuliano. 2002. When finiteness gets marked: The relation between morphosyntactic development and use of scopal items in adult language acquisition. Linguistics 40: 849–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringbom, Hakan, and Scott Jarvis. 2009. The Importance of Cross-Linguistic Similarity in Foreign Language Learning. In The Handbook of Language Teaching. Edited by Catherine J. Doughty and Michael H. Long. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 106–18. [Google Scholar]

- Thörle, Britta. 2020. «Et le chien aussi i’ regarde» particule additive aussi et structure informationnelle en français L2. Language Interaction Acquisition 11: 298–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | We refer the reader to these publications for an extensive presentation of additive particles in different languages. Note that most of such particles are polysemic: in particular, aussi is also a causal connector and auch a modal particle. |

| 2 | A third configuration would be auch in postfinite position with scope over the following part of the sentence. We do not consider such an option, as it goes beyond the topic of our study. |

| 3 | Such preferences have been related to a typological split between Germanic vs. Romance languages for discourse cohesion in additive and contrastive contexts (Benazzo and Dimroth 2015). Auch is integrated in a system of assertion-related particles pushing German speakers to comparisons between assertions (use of its stressed variant, affirmative particles or verum focus), whereas speakers of Romance languages are less systematic in their choice of linguistic means but share a tendency to mark addition and contrast between topic entities (availability of specific means such as strong pronouns or marked word orders) or in the domain of the lexical predicate (expression of identity instead of addition). |

| 4 | The L2 corpus has been collected in the framework of the Franco-German project Langacross II (Utterance Structure in Context: Language and Cognition during acquisition in a crosslinguistic perspective, 2011–2014), financed, respectively, by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche and the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft. Their productions have been studied for the expression of contrastive relations in Benazzo et al. (2012). The control groups of L1 French and German have also been partially considered in other studies, namely, Dimroth et al. (2010), Bonvin and Dimroth (2016) and Benazzo and Paykin (2017). |

| 5 | Their level in French had been assessed either by the institution where some of them were following courses of French as a second language (Italian Erasmus students) or via a language test centered on grammatical competence. |

| 6 | Fr. également can also be used as an adverb of manner meaning “equally”/”in an equal manner”, but all the occurrences attested suggest the additive meaning. |

| 7 | Excerpts report the number of the relevant scene, followed by the subject number. |

| 8 | The use of aussi (instead of non plus) in a negative context is typical of L2 French at the intermediate level (cf. Thörle 2020). Note, however, that such constructions are not unusual in colloquial French. |

| 9 | Note that many preverbal lui aussi do not include an initial NP because the referent is maintained: in these cases, it is not possible to use the clitic pronoun with preverbal aussi (*il aussi…). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).