Clitic-Doubled Left Dislocation in Heritage Spanish: Judgment versus Production Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

| 1. | [clld | A | Pedro] | María | lo | v-e | en | el | parque | (CLLD) |

| DOM1 | Pedro | Maria | Cl.acc | see-3sing | in | the | park | |||

| ‘Pedro, Maria sees him in the park.’ | ||||||||||

1.1. The Test Case: Spanish CLLD

| 2. | María | ve | a | Pedro | en | el | parque | (canonical) |

| Maria | see-3sing | DOM | Pedro | in | the | park | ||

| ‘Maria sees Pedro in the park.’ | ||||||||

| 3. | [CLLD | A | Pedro] | María | lo | v-e | en | el | parque. | (CLLD) |

| DOM | Pedro | Maria | Cl.acc | see-3sing | in | the | park | |||

| ‘Pedro, Maria sees him in the park.’ | ||||||||||

| 4. | [FF | A | PEDRO] | (*lo) | v-e | María | en | el | parque. | (FF) |

| DOM | Pedro | see-3sing | Maria | in | the | park | ||||

| ‘PEDRO Maria sees in the park.’ | ||||||||||

| 5. | [Cleft | A | Pedro] | (*lo) | e-s | a | quien | María | v-e | en | el | parque. | (Cleft) |

| DOM | Pedro | be-3sing | to | whom | Maria | see-3sing | in | the | park | ||||

| ‘Pedro is the one that Maria sees in the park.’ | |||||||||||||

| 6 | CONTEXT: Do you see [ANTECEDENT your family]? | ||||||||

| a. | [CLLD A | mis | hermanos] | los | veo. | ([+a]CLLD) | |||

| dom | my | siblings | Cl.acc.pl | see.1sing | |||||

| ‘My siblings, I see them.’ | |||||||||

| b. | #[CLLD A | mis | amigos] | los | veo. | (#[−a]CLLD) | |||

| dom | my | friends | Cl.acc.pl | see.1sing | |||||

| #’My friends, I see them.’ | |||||||||

| c. | #[FF | A | MIS | HERMANOS] | veo. | (#[+a]FF) | |||

| dom | my | siblings | see.1sing | ||||||

| #‘My siblings, I see.’ | |||||||||

| d. | [FF | A | MIS | AMIGOS] | veo. | ([−a]FF) | |||

| dom | my | friends | see.1sing | ||||||

| ’My friends, I see.’ | |||||||||

| c. | #[Cleft | A | MIS | HERMANOS] | es | a | quien | veo. | (#[+a]Cleft) |

| dom | my | siblings | be.1sing | dom | who | see.1sing | |||

| #‘My siblings are the ones I see.’ | |||||||||

| d. | [Cleft | A | MIS | AMIGOS] | es | a | quien | veo. | ([−a]Cleft) |

| dom | my | friends | be.1sing | dom | who | see.1sing | |||

| ‘My friends are the ones I see.’ | |||||||||

1.2. Hypotheses for Heritage Speakers at the Discourse–Syntax Interface

1.2.1. Divergent Competence

1.2.2. Processing and Production Issues

1.2.3. Convergent Competence Masked by Task Effects

1.2.4. Convergence

1.3. The Present Study

2. Experiment 1—Acceptability Judgment Task

2.1. Methodology

2.1.1. Participants

- 7.

- Lucia: ¿José le trajo los libros al profesor?‘Did Jose bring the books to the professor?’Pedro: Sí, ___________ (Yes, he-brought them to-him)se los trajo

- *

- los se trajo

- *

- trajo

- *

- se trajolos

- *

- trájoselos

2.1.2. Experimental Task

- 8.

- Juan y Mónica están recién casados y se acaban de mudar a su nueva casa. Mónica trabajó todo el díamientras Juan se quedó en casa y acomodó los muebles. Mónica lo llamó para ver cómo estaban las cosas.‘Juan and Monica are newlyweds and have just moved into their new home. Monica worked all day long while Juan stayed at home and arranged the furniture. Monica called him to see how things were going.’Mónica: Entonces, ¿qué hiciste con los muebles?Monica: ‘So, what did you do with the furniture?’

A)Juan: Bueno, sillas las puse en en la cocina, y Well the chairs Cl.ACC.pl put.past.1sing in the kitchen and los sillones los puse en la sala. the armchairs Cl.ACC put.past.1sing in the living-room ‘Well, I put the chairs in the kitchen, and I put the armchairs in the living room.’ B)Juan: #Bueno, las sillas puse en la cocina, y Well the chairs put.past.1sing in the kitchen and los sillones puse en la sala. the armchairs put.past.1sing in the living-room #‘Well, I put the chairs in the kitchen, and I put the armchairs in the living room.’

- 9.

- Juan y Mónica invitaron a María a comer. La cena se sirvió en la terraza y todo estaba muy rico. Maríafelicitó a Juan por la sopa que había hecho. Cuando Mónica escucha esto, responde:‘Juan and Mónica invited Maria for dinner. Dinner was served on the terrace and everything was very tasty. Maria complimented Juan on the soup he made. When Monica hears this, she responds:’

A) Mónica: LA CARNE preparó Juan, no la sopa the meat prepare.3sing.past Juan, NEG the soup ‘Juan prepared the meat, not the soup.’ B) Mónica: # LA CARNE la preparó Juan, no la sopa. the meat Cl.ACC prepare.3sing.past Juan, NEG the soup ‘Juan prepared the meat, not the soup.’

2.1.3. Variables and Analysis

2.2. Results

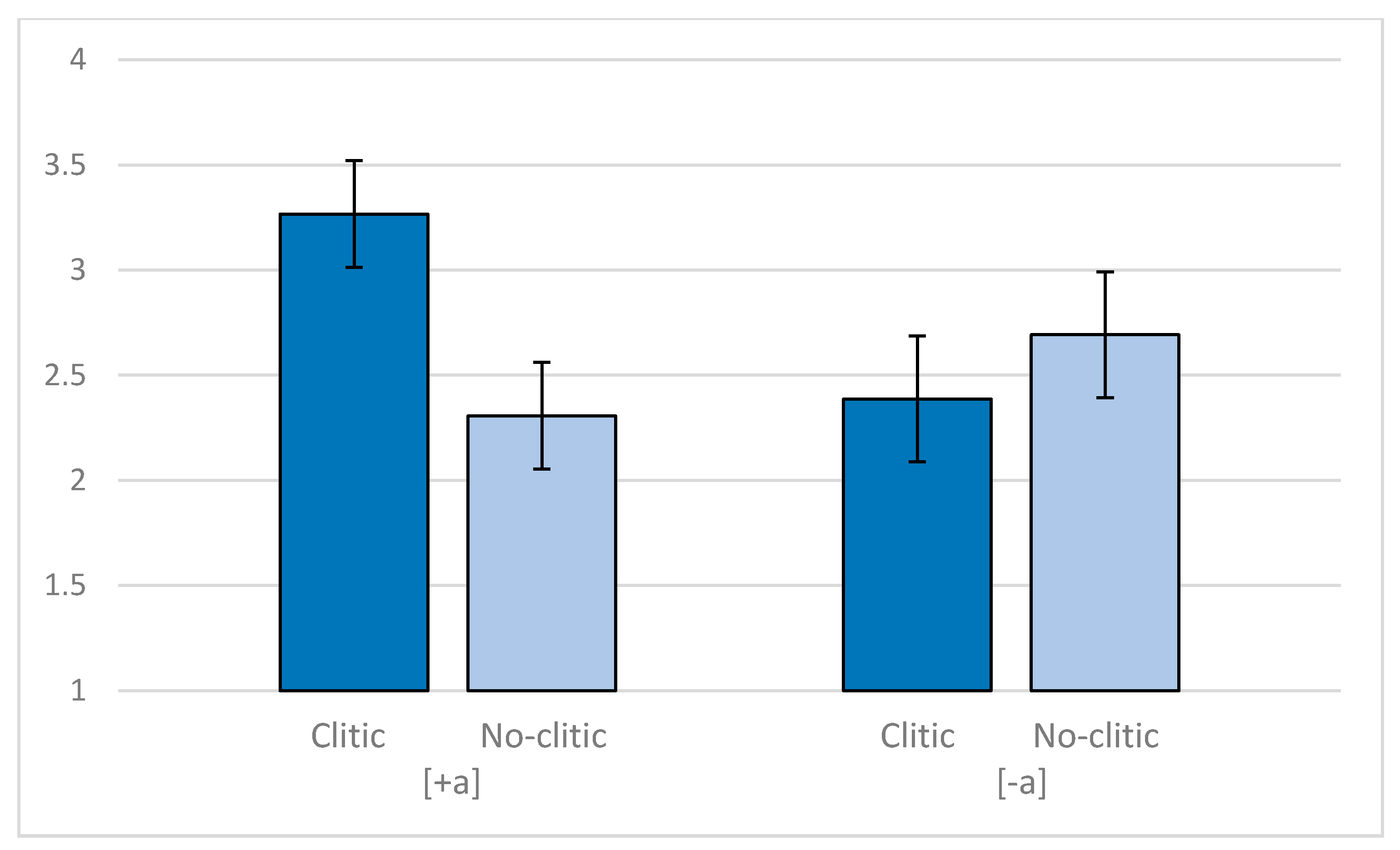

2.2.1. Group Results

2.2.2. Individual Variation

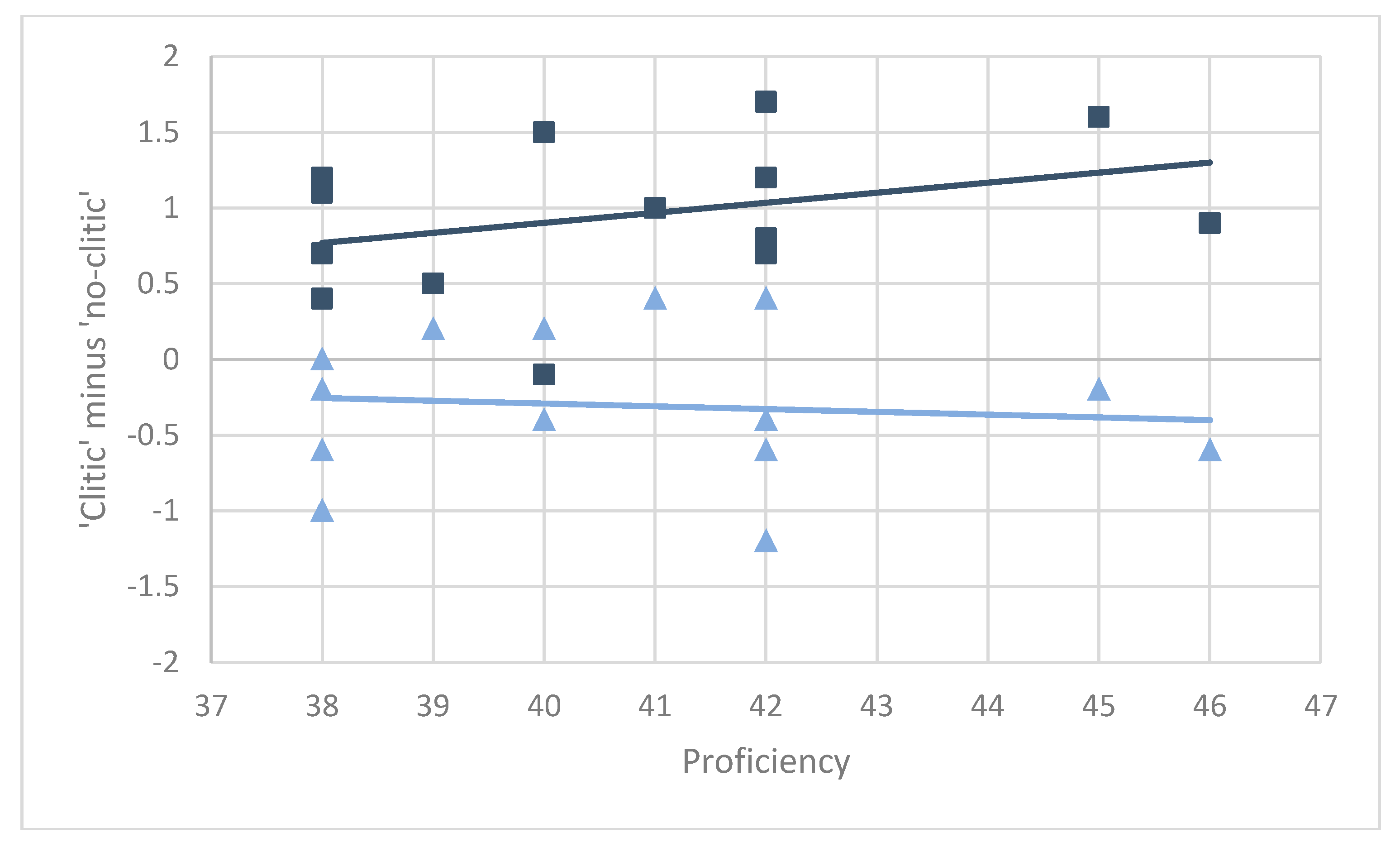

2.2.3. Results by Proficiency Score

2.3. Interim Discussion 1

3. Experiment 2—Speeded Production Task

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Experimental Task

- 10.

- Tus hijos se llaman David y Antonio. Llevas a David al doctor el jueves, y a Antonio el viernes. Juante pregunta:‘Your children are named David and Antonio. You are taking David to the doctor on Thursday, and Antonio on Friday. Juan asks:’

Juan: ¿Cuándo llevas a tus hijos al doctor? When take.2SING DOM your children to-the doctor ‘When are you taking your children to the doctor?’ Tú: A David… DOM David ‘David…’

| 11. | [CLLD | A | David] | lo | llevo | el | jueves. | (CLLD) |

| DOM | David | Cl.ACC | take.1sing | the | Thursday | |||

| A | Antonio | lo | llevo | el | viernes. | |||

| DOM | Antonio | Cl.ACC | take.1sing | the | Friday | |||

| ‘I am taking David in on Thursday. I am taking Antonio in on Friday.’ | ||||||||

- 12.

- Tú traes a tu viejo amigo Rubén a una fiesta. Juan hace un comentario, pero quieres decirle que tú traesa Rubén y no a Carlos:‘You bring your old friend Rubén to a party. Juan makes a comment, but you want to tell him that you are bringing Rubén and not Carlos:’

Juan: ¡Gracias por traer a Carlos a la fiesta! ‘Thanks for bring.INF DOM Carlos to the party!’ Tú: ¡No!9 ¡A Rubén…‘No! DOM Rubén…’

| 13 a. | ¡No! | ¡A | Rubén | traigo | a | la | fiesta! | (FF) | ||

| NEG | DOM | Ruben | bring.1sing | to | the | party | ||||

| ‘No! Rubén I bring to the party!’ | ||||||||||

| b. | ¡No! | ¡A | Rubén | es | al | que traigo | a | la | fiesta! | (Cleft) |

| NEG | DOM | Ruben | is | DOM.the-one | that bring.1sing | to | the | party | ||

| ‘No! Rubén is the one I bring to the party.’ | ||||||||||

3.1.3. Variables and Analysis

3.2. Results

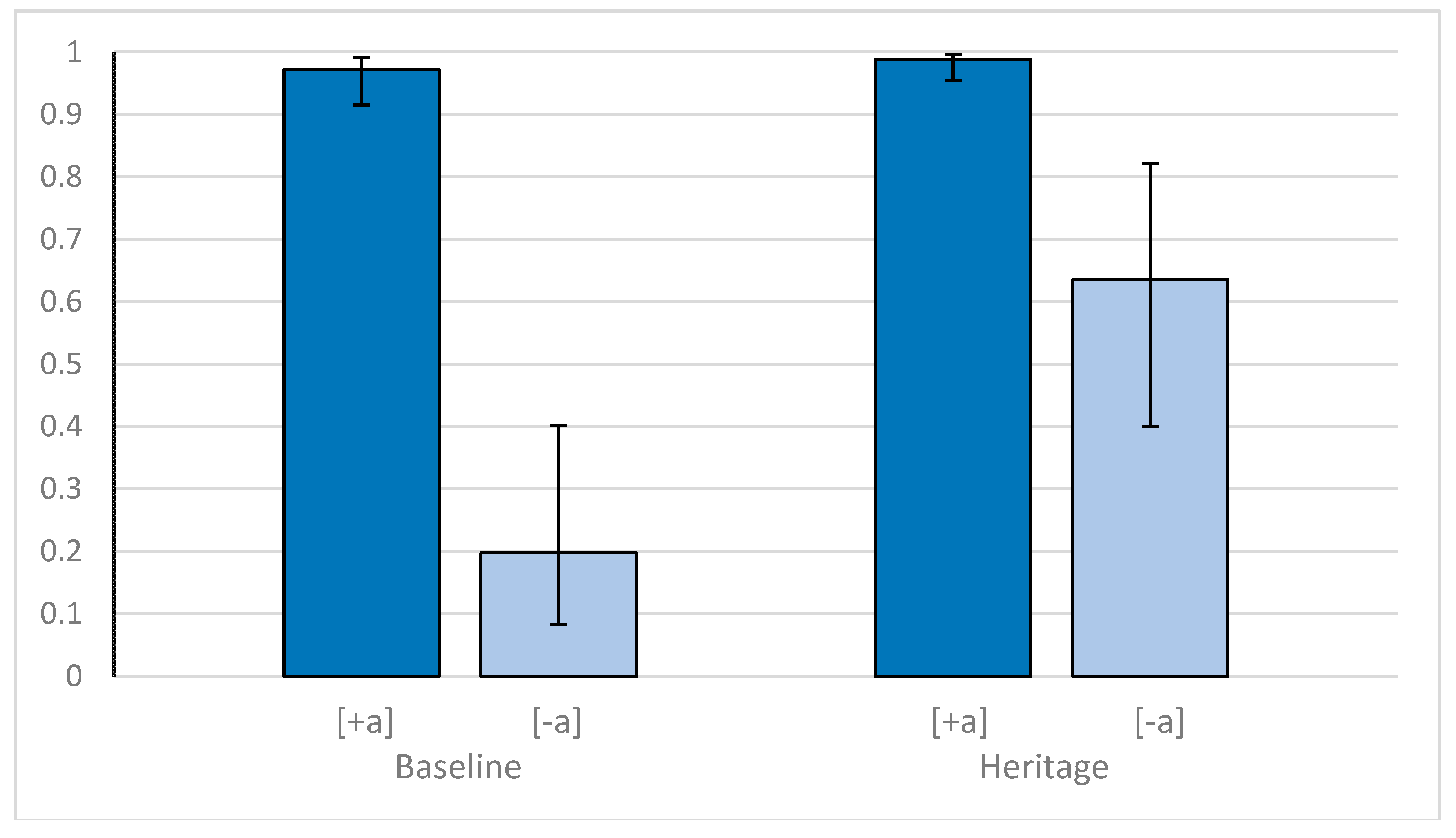

3.2.1. Group Results

3.2.2. Individual Variation

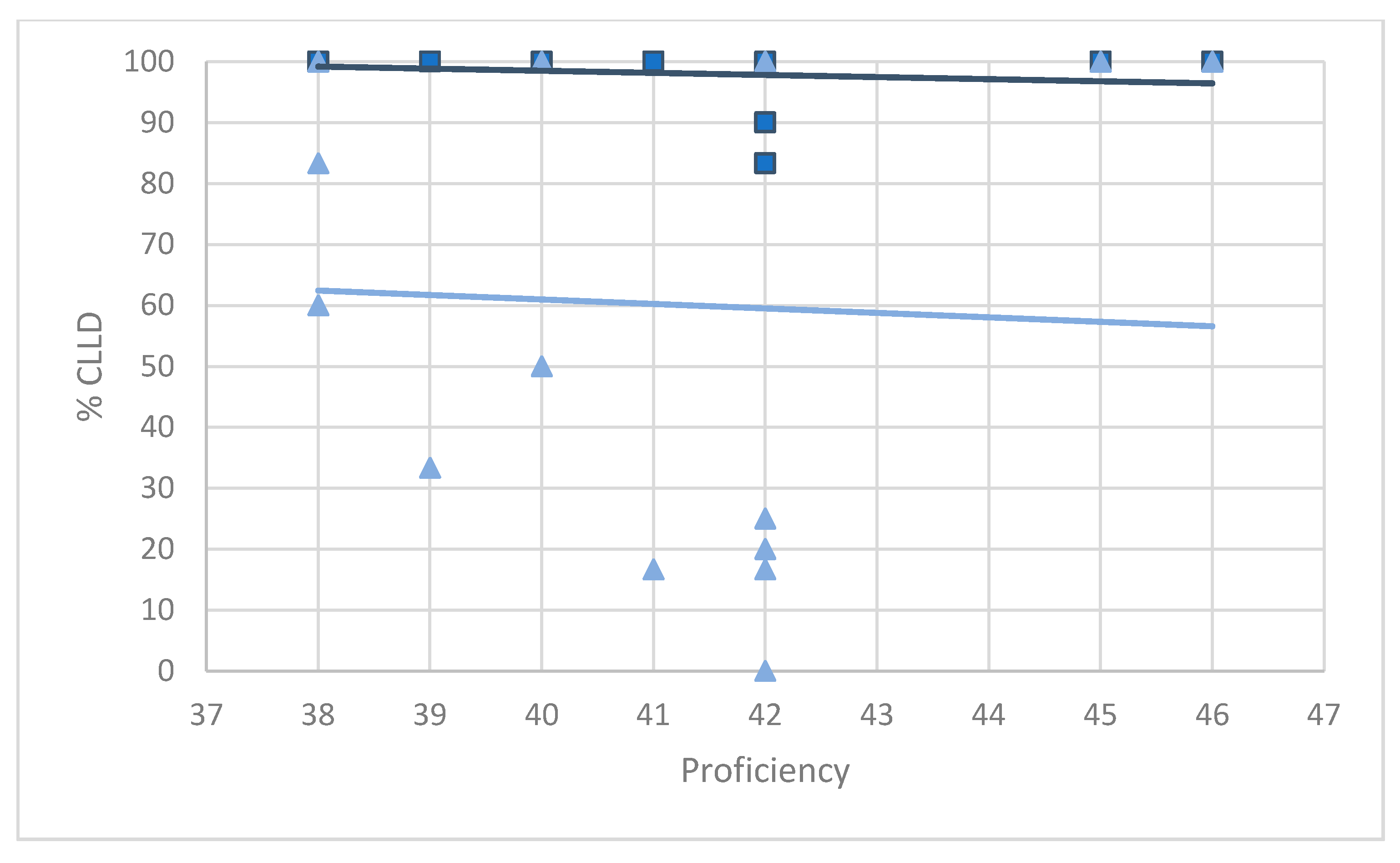

3.2.3. Results by Proficiency Score

3.3. Interim Discussion 2

4. General Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Results

4.2. Is Heritage Speaker Convergence Possible at the Syntax/Discourse Interface?

4.3. Sources of Divergence

4.4. An Alternative Explanation

4.5. The Role of Proficiency

4.6. The Role of the Population: Heritage vs. L2 Speakers

4.7. Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers, and Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68: 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, Adriana, Elisa Bennati, and Antonella Sorace. 2007. Theoretical and developmental issues in the syntax of subjects: Evidence from near-native Italian. Natural Language Linguistic Theory 25: 657–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013a. Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 129–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013b. Defining an ‘ideal’ heritage speaker: Theoretical and methodological challenges|Reply to peer commentaries. Theoretical Linguistics 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Valentina, and Mara Frascarelli. 2010. Is topic a root phenomenon? Iberia: An International Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 2: 43–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrelli Amaro, Jennifer. 2017. Testing the phonological permeability hypothesis: L3 phonological effects on L1 versus L2 systems. International Journal of Bilingualism 21: 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Mark. 2006. A Frequency Dictionary of Spanish. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, Nigel. 2018. Reflections on Psycholinguistic Theories. Raiding the Inarticulate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Rod. 2009. The differential effects of three types of task planning on the fluency, complexity, and accuracy in L2 oral production. Applied Linguistics 30: 474–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldhausen, Ingo. 2016. Interspeaker variation, Optimality Theory and the prosody of clitic left-dislocations in Spanish. Probus 28: 293–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldhausen, Ingo, and Maria del Mar Vanrell. 2015. Oraciones hendidas y marcación del foco estrecho en español: Una aproximación desde la Teoría de la Optimidad Estocástica. Revista Internacional De Lingüística Iberoamericana 26: 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Giancaspro, David. 2015. Code-switching at the auxiliary-VP Boundary. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 5: 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, Therese, Casey Lew-Williams, and Anne Fernald. 2012. Grammatical gender in L2: A production or a real-time processing problem? Second Language Research 28: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoot, Bradley. 2017. Narrow presentational focus in heritage Spanish and the syntax-discourse interface. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 7: 63–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulk, Aafke, and Natascha Müller. 2000. Bilingual first language acquisition at the interface between syntax and pragmatics. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koornneef, Arnaout W., Sergey Avrutin, Frank Wijnen, and Eric Reuland. 2011. Tracking the preference for bound-variable dependencies in ambiguous ellipses and only-structures. In Experiments at the Interfaces. Edited by Jeffrey Runner. Leiden: Emerald Publishers/Brill, pp. 67–100. [Google Scholar]

- Laleko, Oksana, and Maria Polinsky. 2013. Marking topic or marking case: A comparative investigation of heritage Japanese and heritage Korean. Heritage Language Journal 10: 40–64. [Google Scholar]

- Laleko, Oksana, and Maria Polinsky. 2016. Between syntax and discourse: Topic and case marking in heritage speakers and L2 learners of Japanese and Korean. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 6: 396–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laleko, Oksana, and Maria Polinsky. 2017. Silence is difficult: On missing elements in bilingual grammars. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 36: 135–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Sean P., and Erin P. Hennes. 2018. Power struggle: Estimating sample size for multilevel relationships research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 35: 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2011. Who is the Interface Hypothesis about? Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, Tania. 2018. Data analysis and sampling. In Critical Reflections on Data in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Aarnes Gudmestad and Amanda Edmonds. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, Tania, Emilie Destruel, and Bradley Hoot. 2018. The realization of information focus in monolingual and bilingual native Spanish speakers. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 8: 217–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Méndez, Tania, Jason Rothman, and Roumyana Slabakova. 2015. Discourse-sensitive clitic-doubled dislocations in heritage Spanish. Lingua 155: 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightbown, Patsy, and Nina Spada. 2006. How Languages are Learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- López, Luis. 2009. A Derivational Syntax for Information Structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, Emma, Kara Morgan-Short, Sophie Thompson, and David Abugaber. 2018. Replication in second language research: Narrative and systematic reviews and recommendations for the field. Language Learning 68: 321–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, Sashiko. 2003. Instructional needs of college-level learners of Japanese as a heritage language. Performance based analysis. Heritage Language Journal 1: 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2002. Incomplete acquisition and attrition of Spanish tense/aspect distinctions in adult bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 5: 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2004. Subject and object expression in Spanish heritage speakers: A case of morphosyntactic convergence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2008. Incomplete Acquisition in Bilingualism: Re-examining the Age Factor. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2014. Structural changes in Spanish in the United States: Differential object marking in Spanish heritage speakers across generations. Lingua 151: 177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Maria Polinsky. 2011. Why not heritage speakers? A response to Sorace. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, Rebecca Foote, Silvia Perpiñán, Dan Thornhill, and Susana Vidal. 2006. Full access and age effects in adult bilingualism: An investigation of accusative clitics and word order. In Selected Papers from the Hispanic Linguistic Symposium. Edited by Nuria Sagarra and Jacqueline Toribio. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 217–28. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina, Rebecca Foote, and Silvia Perpiñán. 2008. Gender agreement in adult second language learners and Spanish heritage speakers: The effects of age and context of acquisition. Language Learning 58: 503–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, Rakesh Bhatt, and Roxana Girju. 2015. Differential object marking in Spanish, Hindi, and Romanian as heritage languages. Language 91: 564–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2006. Incomplete acquisition: American Russian. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 14: 191–262. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2016. Structure vs. use in heritage language. Linguistics Vanguard 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2018. Heritage Languages and Their Speakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2020a. Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 22: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2020b. A roadmap for heritage language research: Response to the commentaries. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, Carson T., and Jon Sprouse. 2013. Judgment data. In Research Methods in Linguistics. Edited by Robert J. Podesva and Devyani Sharma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeros-Valle, Jose. 2020. A Morphological Approach to Discourse in Spanish: A Theoretical and Experimental Review. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeros-Valle, Jose, Bradley Hoot, and Jennifer Cabrelli. 2020. Clitic-doubled left dislocation in L2 Spanish: The effect of processing load at the syntax-discourse interface. Language Acquisition 27: 306–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1994. Language Contact and Change: Spanish in Los Angeles. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slabakova, Roumyana, Paula Kempchinsky, and Jason Rothman. 2012. Clitic-doubled left dislocation and focus fronting in L2 Spanish: A case of successful acquisition at the syntax-discourse interface. Second Language Research 28: 319–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2011. Pinning down the concept of ‘interface’ in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2012. Pinning down the concept of interface in bilingual development: A reply to peer commentaries. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 2: 209–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Francesca Filiaci. 2006. Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second Language Research 22: 339–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprouse, Jon, and Diogo Almeida. 2017. Setting the empirical record straight: Acceptability judgments appear to be reliable, robust, and replicable. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 40: E311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi, and Antonella Sorace. 2006. Differentiating interfaces: L2 performance in syntax semantics and syntax discourse phenomena. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by David Bamman, Tatiana Magnitskaia and Colleen Zaller. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 653–64. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, Elena. 2006. L2 end state grammars and incomplete acquisition of Spanish CLLD constructions. In Inquiries in Linguistic Development: In Honor of Lydia White. Edited by Roumyana Slabakova, Silvina Montrul and Philippe Prévost. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- White, Lydia. 2011. The Interface Hypothesis? Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 108–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Lydia, n nonnatiElena Valenzuela, Martina Kozlowska-MacGregor, and Yan-Kit I. Leung. 2004. Gender and number agreement ive Spanish. Applied Linguistics 25: 105–33. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | DOM = Differential object marker, which here marks a constituent as an [+animate, +specific] direct object. |

| 2 | Sorace (2011) excludes heritage speakers from the scope of the hypothesis. Yet others (Montrul and Polinsky 2011; Hoot 2017) have argued that the hypothesis should be extended to this population, a position Sorace (2012, p. 214) accepts “as long as the differences between individual and generational attrition are clear”. |

| 3 | Although the initial formulation of this hypothesis compared “narrow syntax” to interface structures, Sorace (2011, p. 10) recognizes that it is “difficult to identify structures that are sensitive to exclusively syntactic constraints” while also noting that researchers have “repeatedly emphasized syntactic principles and dependencies as having a different status from non-syntactic ones in terms of acquisition and processing”. |

| 4 | As reported in Leal Méndez et al. (2015), these 25 fillers included five corrective focus clitic-doubled right dislocation (CLRD), five ambiguous CLRD, five Rheme constructions, and 10 additional constructions that did not manipulate information structure. |

| 5 | We used the original voice recordings from Leal Méndez et al. (2015), and they were at least a male and a female native speaker of Mexican Spanish, but we do not have additional information. Furthermore, each and every word presented visually was also presented aurally, and vice versa. |

| 6 | All figures generated in Microsoft Excel. |

| 7 | First, within each condition ([+a] and [−a]), we looked at whether the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of each participant’s mean ratings for sentences with clitics overlapped with the 95% CI of their ratings of clitic-less sentences. If the two ranges did not overlap, we took it as evidence that the speaker treated each construction type differently. However, like with the one-point difference, only eight of the 14 baseline group showed the expected differences, making this an invalid procedure for our data. Second, within each condition ([+a] and [−a]), we calculated the 95% CI of the difference between clitic-ed and clitic-less sentence for the baseline group overall ([+a] = 0.84–1.61; [−a] = −1.36–−0.52). This second system, obviously, does not create any issues within the baseline group. However, we later considered that this is the type of between-group comparison that we were to avoid. To address this limitation going forward, as very helpfully noted by an anonymous reviewer, we can incorporate statistical methods such as Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (BLUP), which allows for the estimation of random effects whereby model predictions for each participant can be extracted. |

| 8 | The aural stimuli were recorded by the first author (male L1 Peninsular Spanish/late L2 English speaker) and a female (female L1 Peninsular Spanish/late L2 English speaker). The context and question were presented aurally, while the beginning of the answer was only presented visually. |

| 9 | López (2009) notes the following about the inclusion of negation preceding this type of utterance: “Since negation does the contrastive work, the focused constituent may just be plain information focus and the function ‘contrast’ and ‘focus’ are distributed among two different constituents” (p. 56). However, negation was included to help the participant understand that the focus would go to Rubén, and not Carlos. Although the presence of negation may explain the overextension of CLLD to [−a] discourse contexts in our group results, the baseline participants were able to consistently distinguish between [+a] and [−a] discourse contexts. |

| 10 | These six fillers included dative experiencer predicates (verbs like gustar ‘to like’) in order to force the presence of a preposition a ‘to’ at the beginning of the sentence, as a parallel to the DOM in the experimental items. |

| Prediction | Summary | Expected Task Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AJT | SPT | ||

| Divergent competence | Heritage speakers acquire a grammar with different features than the grammar of baseline speakers | Unlike baseline (because grammars are different) | Unlike baseline (because different grammars are reflected in production) |

| Processing and production issues | Heritage speakers acquire a grammar like the baseline, but processing resource limitations reduce their ability to integrate knowledge in real time | Like baseline (reflecting offline competence) | Unlike baseline (reflecting processing breakdown due to increased resource load of timed production) |

| Convergent competence masked by task effects | Heritage speakers acquire a grammar like the baseline, but certain task types (especially AJTs) are inappropriate for them; some previous results are thus potentially misleading | Unlike baseline (due to task effects) | Like baseline (more naturalistic task reveals real competence) |

| Convergence | Heritage speakers acquire a grammar like the baseline and process it without difficulty | Like baseline | Like baseline |

| Hypothesis | AJT | SPT |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence | Convergence | Convergence |

| Processing and production issues | Convergence | Divergence |

| Convergence competence masked by task effects | Divergence | Convergence |

| Divergent competence | Divergence | Divergence |

| n | Proficiency (1–50) | Clitics (1–50) | Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Baseline | 14 | - | - | - | - | 30.00 | 6.90 |

| Heritage speakers | 15 | 40.87 | 2.50 | 47.47 | 1.96 | 20.80 | 2.42 |

| Hypothesis | AJT | SPT |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence | Convergence | Convergence |

| Processing and production issues | Convergence | Divergence |

| Convergence competence masked by task effects | Divergence | Convergence |

| Divergent competence | Divergence | Divergence |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sequeros-Valle, J.; Hoot, B.; Cabrelli, J. Clitic-Doubled Left Dislocation in Heritage Spanish: Judgment versus Production Data. Languages 2020, 5, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040047

Sequeros-Valle J, Hoot B, Cabrelli J. Clitic-Doubled Left Dislocation in Heritage Spanish: Judgment versus Production Data. Languages. 2020; 5(4):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040047

Chicago/Turabian StyleSequeros-Valle, Jose, Bradley Hoot, and Jennifer Cabrelli. 2020. "Clitic-Doubled Left Dislocation in Heritage Spanish: Judgment versus Production Data" Languages 5, no. 4: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040047

APA StyleSequeros-Valle, J., Hoot, B., & Cabrelli, J. (2020). Clitic-Doubled Left Dislocation in Heritage Spanish: Judgment versus Production Data. Languages, 5(4), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040047