Abstract

Rhotic assibilation is a common sociolinguistic variable observed in different Spanish speaking countries such as Argentina, Ecuador, and México. Previous studies reported that rhotic assibilation alternates with the flap and/or with the trill. In this study, we explore three aspects of rhotic assibilation in the Spanish of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico/El Paso, TX, United States: (1) Its diachronic development; (2) the linguistic and social factors that affect this variation and; (3) the possible effect of contact with English in this variable. Fifty-eight participants, including Spanish monolingual and Spanish-English bilingual subjects, performed one formal and two semi-informal speech production tasks. Acoustic and perceptual analysis of the tokens showed that the variation is not binary (standard vs. non-standard variant), but that it includes other rhotic variants with varying degrees of frication. Variation is restricted to phrase-final position and heavily favored by preceding front vowels (/e/ and /i/). These effects have a clear aerodynamic and articulatory motivation. Rhotic assibilation is not receding, as previously reported. It continues to be a prestigious variable prevalent amongst females, but also present in male speakers. The comparison between bilingual and monolingual speakers shows that contact with English does not significantly affect the occurrence of assibilation.

1. Introduction

Rhotic assibilation is a pervasive feature of most varieties of Spanish. It has been reported in Argentina (Colantoni 2006); Bolivia (Morgan and Sessarego 2016); Costa Rica (Vásquez Carranza 2006); Ecuador (Bradley 2004); Spain (Henriksen and Willis 2010); Dominican Republic (Willis 2007); and Mexico (Amastae et al. 1998; Bradley and Willis 2012; Eller 2013; Lope Blanch 1967; Perissinotto 1972; Rissel 1989). Although assibilation is a common feature in all these dialects, social and linguistic factors seem to influence the phonological feature in unique ways. In this study, we focus on rhotic assibilation in the Spanish of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico/El Paso, TX, United States. We explore three aspects of rhotic assibilation: (i) The development of this feature more than two decades after the first (and only) study was conducted in this same dialect (Amastae et al. 1998); (ii) the linguistic and social factors that affect this variation; and (iii) whether contact with English affects the variable in bilinguals.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 1 reviews the phonetic and phonological characteristics of rhotics, the sociolinguistic literature on rhotic assibilation in Mexico City and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Section 2 details the methodology for the study. Section 3 introduces the results, and Section 4 answers the research questions and relates the findings of the present study with the literature reviewed. Finally, we conclude and discuss the future directions of this research.

1.1. Phonological, Articulatory, and Acoustic Characteristics of Spanish Rhotics

With regard to rhotic distribution, there is a clear distinction between the syllabic positions that can be occupied by taps and trills. Taps /ɾ/, as in caro /káɾo/ ‘expensive’, and trills /r̄/, as in carro /kár̄o/ ‘car’, contrast in word-internal intervocalic position (Hualde 2005). In word-initial position and after a consonant in a different syllable, only the trill occurs: Rosa /r̄ósa/ ‘rose’ and Israel /isr̄aél/. The tap occurs in onset clusters: Prosa /pɾósa/ ‘prose’ and in word-final position before a vowel: Ser amigos /séɾ amíɡos/ ‘to be friends’. A variable rhotic appears in coda position (within a word or across word boundaries) followed by a consonant or a pause, i.e., when resyllabification is not possible. While a tap is more frequently found in these contexts, an emphatic trill can also occur1 e.g., arte a[r̄]te or á[ɾ]te ‘art’, amor amo[ɾ] or amo[r̄] ‘love’. Following Hualde (2005), we will use the symbol /r/ to represent the non-distinct rhotic found in final position where there is no possible resyllabification. We will also use the neutral term ‘rhotic’ rather than ‘tap’ and ‘trill’ to refer to it.

Articulatorily, standard taps and trills2 share the same place and manner of articulation; they are both usually realized as voiced and alveolar3. The main difference between taps and trills is that taps are produced with a single contact between the tip of the tongue towards the alveolar ridge, while trills are produced with several (usually two or three) such rapid contacts (Hualde 2005). Navarro Tomás (Tomás [1918] 1970, pp. 1, 116) gave a more detailed description of the Spanish trill that specifies the position of the tongue tip, dorsum, and root. He stated that the tip of the tongue bends upwards to touch the upper-most part of the alveolar ridge, the tongue root retracts towards the back of the oral cavity, and the tongue body adopts a hollow or concave shape.

The realization of trills requires a complex combination of articulatory movements of the tongue-tip and aerodynamic forces (Solé 2002). Due to their articulatory complexity, trills are mastered late in the L1 acquisition and are not present in the babbling stage. Not only do native speakers find trills challenging, but L2 learners may also find them difficult to acquire and some may never succeed in rolling their [r]s (Solé 2002). Because the production mechanism of trills is quite complex and requires precise articulatory and aerodynamic conditions, small changes in their production can lead to perceptible acoustic differences. These small changes in the production of trills, which could be due to contextual or prosodic features, create a favorable environment for the instability of this sound and the creation of new variants. In fact, the rich literature on rhotic variation in different dialects of Spanish provides evidence for the instability of trills and, most importantly, the methodological challenges they present in their analysis (see Method section).

Acoustically, the tap and the trill share the same characteristics: A lowered third formant (Colantoni 2001) and brief periods of occlusion, one occlusion for the tap and more than one for the trill. However, taps and trills differ in the duration of the segment, with taps being shorter than trills. Quilis (1993) reported an average of 20 ms. for taps and 60 ms. for trills. The length of the trill is affected by the following vowel: It is shorter before [i] and longer before [a] (Solé 2002).

Assibilated and standard rhotics4 tend to alternate synchronically and diachronically (Solé 1992). Synchronically, apical trills exhibit non-trilled variants, taps, approximants, and fricatives. Solé (2002) performed a study to replicate the phonological variation between voiced trills and fricatives. Her results showed that trills may become fricatives (or assibilated) if the finely controlled articulatory or aerodynamic requirements for trills are not met, suggesting that fricatives involve a less complex articulation and allow a wider range of oropharyngeal pressure variation than trills. Thus, assibilated rhotics occur when the vibrating tongue-tip fails to make contact with the palate, or when apical vibration fails, allowing the high velocity air to flow continually through the aperture generating frication (Solé 2002). She further stated that assibilated rhotics in phrase-final position result from the difficulty of sustaining trilling with the lowered decreased subglottal pressure that occurs at the end of a statement.

Since this is a natural phenomenon, Solé (2002) argued that the co-occurrence of trilling and frication (or standard and assibilated rhotics) should be a common cross-linguistic pattern. In fact, rhotic assibilation (mainly in phrase-final position) has been reported in many dialects of Spanish (Blecua and Cicres 2019; Canfield 1981; Quilis 1981), in other Romance and non-Romance languages such as Brazilian Portuguese (Silva 1996), Czech (Howson et al. 2014), and in Farsi (Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996). Solé (2002) replicated in the laboratory the variation observed in different languages.

1.2. Sociolinguistic Literature on Rhotic Assibilation in Mexico City

Assibilated taps and trills were first studied in Mexico City by Lope Blanch (1967). The author (Lope Blanch 1967) argued that assibilation was a recent phenomenon that appeared after the 1950s in the speech of women. He suggested that assibilation might have been imported from Spain, because it had been observed there and in several other Latin-American countries. Lope Blanch (1967) proposed that rhotic assibilation is a natural process in the evolution of the phonological system of languages. Unfortunately, this last point was not developed further, but it is explored in the laboratory by Solé (2002), summarized above.

The first synchronic sociolinguistic analysis of rhotic assibilation in Mexico City was published by Perissinotto (1972). The study was based on 110 h of recorded conversation (the number of participants was not stated) collected between 1963 and 1969. His results showed a high overall percentage of assibilation (68.2%). Female speakers had a higher rate of the assibilated rhotic [ř] compared to their standard variant [r] ([ř] 81.8% vs. [r] 18.2%) while male speakers had a reverted pattern of variation: A higher percentage of the standard variant compared to the assibilated one ([r] 61.1% vs. [ř] 38.9%). By comparing the distribution of the assibilated variant across age and socio-economic status, Perissinotto (1972) found that assibilation was more common in the younger age group and in the high and middle socio-economic levels. In other words, assibilation was a prestigious innovative variant adopted by women of the higher classes.

More than three decades after the first study, Martín Butragueño (2006) performed an analysis of rhotic assibilation in 54 native speakers of Mexico City. The overall percentage of assibilation in absolute final position was 27%, compared to the 68.1% reported by Perissinotto (1972). A multivariate analysis of rhotic assibilation showed a number of linguistic and social factors that favored assibilation: (1) Absolute final position; (2) formal style; (3) mid and high education; (4) older generation; and (5) females. Martín Butragueño (2006) claimed that given the lower percentage of assibilation found in his study, as compared to Perissinotto’s (1972), rhotic assibilation seemed to be a receding case of language change. This conclusion was reinforced by the fact that assibilation was more frequent in older women, followed by the adult and younger groups (36%, 32%, and 17%, respectively). This is a tendency in the other direction of what Perissinotto (1972) had found with assibilation being more frequent in younger speakers, followed by adults and older speakers (73.5%, 64.5%, and 31.3%, respectively). The comparison of assibilation found by Perissinotto (1972) and Martín Butragueño (2006) seems to indicate that rhotic assibilation was a short-lived fashion in Mexico City.

Martín Butragueño’s (2014) second study analyzed the speech of 54 interviews and reading tasks from the Sociolinguistic Corpus of Mexico City. The subjects were distributed along the different social categories of age, sex, and education level. The study took into consideration all rhotic positions including coda, onset and consonant cluster, word final, and absolute final. A multivariate analysis confirmed what had been reported previously for rhotic assibilation. Presented in order of importance, assibilation was favored by: (1) Phrase-final position; (2) interview (as opposed to reading); (3) consonant clusters (especially /tr/); (4) people with medium level of instruction (10–12 years); (5) female speakers; and (6) older speakers (55+ years old). Other coda positions were not selected as significant by the multivariate analysis and the author reported very few cases of assibilation in positions other than absolute final and in consonant cluster /tr/.

Martín Butragueño (2014) presented some spectrograms of trill and taps to illustrate the different types of rhotics found in Mexico City Spanish. Besides the standard variants, he also found approximant variants, which the author defined as weakened versions of standard rhotics, and assibilated rhotics. He proposed that rhotic assibilation be described as change from an approximant to a fricative sound. According to the author, this becomes evident in the cases where the rhotic starts as an approximant (with a clear sonority bar and no noise) and continues as a fricative with high frequency noise and an almost inexistent F0. However, as demonstrated by Solé (2002) in the laboratory, there is compelling cross-linguistic evidence suggesting that trills alternate with fricatives (or assibilated variants), so it is plausible that assibilated rhotics result from “a failure of sustaining trilling with the lowered decreased subglottal pressure that occurs at the end of a statement” (Solé 2002).

1.3. Sociolinguistic Literature on Rhotic Assibilation in the State of Chihuahua, Mexico

Rhotic assibilation reached the north of Mexico after the 1960s, with the first study conducted in Ciudad Juárez in 1998 (Amastae et al. 1998). This study showed that assibilation was present in Ciudad Juárez, but with a lower frequency of overall occurrence than reported in Mexico City. The percentage of assibilation in all final positions (including word final and phrase-final) was 6%, while the percentage of assibilation in absolute final position was 22%. Compared to the 68.1% reported by Perissinotto (1972), assibilation was much less frequent in Ciudad Juárez. Amastae et al. (1998) conducted a multivariate analysis on 72 speakers and found that assibilation was affected by: (1) Gender: Higher rate of assibilated rhotics in women (women 28% and men 16%); (2) social class: Greater percentage of assibilation in the higher socio-economic class as compared to the middle class5 (21% and 18%, respectively); (3) age: Adults (36–55 years) and older participants (56+) showed higher rates of assibilation (31% and 19%, respectively) than younger participants (15%); and (4) education: Assibilation was more frequent in speakers with higher levels of formal education (university 23% and high school 14%). All these effects suggested that assibilation was also a prestigious variant in Ciudad Juárez. Amastae et al. (1998) argued that assibilation in Ciudad Juárez was a recent “change from above” (Labov 1972) imported from Mexico City by the higher classes and transmitted by women. According to Labov (1972), a change from above is a linguistic change that enters the language from above the level of consciousness; that is, speakers are generally aware of the linguistic form and they manipulate its use depending on the context and/or their interlocutors. The upper classes use these new linguistic forms in order to differentiate themselves from the lower classes, while lower classes use these forms in order to sound more formal and similar to the upper classes.

Twenty years after Amastae’s study, Mazzaro and González de Anda (2019) investigated the relationship between the perception and production of rhotic assibilation [ř] and deaffrication of the voiceless post-alveolar affricate [ʃ] in the Spanish of Chihuahua, Mexico. Thirty-three native Spanish speakers from the state of Chihuahua completed production and perception tasks to establish whether those that produced the variants were able to perceive them. The production data were elicited by asking participants to narrate the fairy tale Caperucita Roja ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ and by asking them to talk about their favorite food. Results showed that the overall percentage of [ř] production was greater than that of [ʃ] (17.15% and 11.83%, respectively). The authors explained that the increased overall rate of [ř] might be due to assibilation only being investigated in absolute final position, which is the context where most of the variation occurs. The social factors that turned out to be significant were gender and generation, with female and younger speakers favoring the use of assibilation. The relationship between production and perception of assibilation was very subtle; overall, the perception of the variant was very low (9.1%). Those who produced assibilation were not the ones that perceived it the most, which seemed to suggest that rhotic assibilation was below the level of consciousness and social awareness (Labov 2001).

To the best of our knowledge, no other sociolinguistic studies have been done on rhotic assibilation in this geographic area. The present research will further investigate the social and linguistic factors that affect the production of this variable. We also add another layer of analysis to increase the accuracy of coding of tokens, by supplying the auditory classification of tokens with a spectrographic analysis. Acoustic information will allow us to identify if there are other variants that could also be alternating with assibilated rhotics.

This study is designed to explore different aspects of the production of rhotic assibilation in the state of Chihuahua/El Paso, TX speech community6. Our specific questions are the following:

- i.

- What is the current state of rhotic assibilation more than two decades after the first (and only) study was done? In this study, we expect to find a lower frequency of rhotic assibilation, since previous studies on this same dialect (Amastae et al. 1998) stated that this variable was receding.

- ii.

- Which rhotic variants are found in Chihuahua Spanish? Given that Amastae et al. (1998) suggested that assibilation is receding, we predict that we will find a much smaller percentage of rhotic assibilation than he did in 1998, and a large percentage of standard variants (taps and trills). It is possible that we could find other variants reported in other dialects of Mexican Spanish such as approximants, retroflex, and fricatives (Martín Butragueño 2006).

- iii.

- What are the most important linguistic and social correlates of rhotic assibilation? Gender is expected to be one of the most significant factors that influence the variable under study. The fact that female speakers favor assibilation has been consistently reported by Amastae et al. (1998); Lope Blanch (1967); Martín Butragueño (2006); and Perissinotto (1972). Besides gender, we anticipate older speakers to produce more assibilation than the other age groups, which is due to the receding status of the variant (Amastae et al. 1998). The literature on rhotic assibilation agree that the phrase-final position is the most favoring phonetic context for assibilated rhotics. Thus, in this study, we focus on rhotic production in absolute final position. Finally, the preceding vocalic context was found to be significant in our previous analysis of rhotic assibilation (Mazzaro and González de Anda 2016), so we predict that with more data, this factor will show a clearer and more robust effect.

- iv.

- Does being a Spanish-English bilingual affect the use of this variable? Previous work (Dalola and Bullock 2017) found that being bilingual affects the social perception and production rates of variables in the L2. However, our participants are all L1 speakers of Spanish, so we do not expect the L2 English to affect the rate of assibilation in bilingual compared to monolingual speakers.

- v.

- What is the effect of the formality of the task (style): Reading vs. narrative vs. conversation on the occurrence of assibilation? Given the prestige attached to assibilated rhotics (Amastae et al. 1998; Perissinotto 1972), we predict that tasks that are more formal would elicit higher instances of assibilation. Therefore, the reading task will elicit a higher percentage of assibilation than the narrative and the informal conversation. As the formality of the task decreases, so will the frequency of assibilated rhotics.

- vi.

- Does assibilation remain a prestigious feature of speech? We expect that rhotic assibilation will continue to be a prestigious feature of speech. This is based on the vast amount of literature that report the assibilated variant to be used in higher social classes and subjects with higher levels of formal education (Amastae et al. 1998; Martín Butragueño 2006, 2014; Perissinotto 1972).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Speakers

Participants of this study are native Spanish speakers recruited in the El Paso, Texas—Ciudad Juárez, Mexico border area. A total of 58 subjects participated in this study: 36 women and 22 men, with an age range between 18 and 69 years. To compare our data with Amastae et al.’s (1998) generational groups, the participants were divided into four groups: Generation 1: <20; Generation 2: 21–35; Generation 3: 36–55; and Generation 4: >56.

Participants were asked to complete an adult language background questionnaire that elicits information about their place of birth, language(s) of schooling, and language use. The questionnaire contained a section that asked for participants’ self-proficiency ratings in both Spanish and English, and only those who reported to use mostly/only Spanish in their daily everyday interactions (at home, at work, and in social situations) were selected to participate in the study. We considered bilingual those participants who reported to know another language and self-assessed their English knowledge as higher than basic. The demographic information of the participants considered in the statistical analysis is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic information.

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Texas at El Paso IRB (Project identification code [274707-10]).

Thirty-four participants were recruited at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). Some were students enrolled in beginner-level ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages). Seven participants were students at the Universidad Tecnológica de Ciudad Juárez. The remaining 17 participants were contacted using the ‘friend-of-a-friend’ technique (Milroy 1987), whereby potential informants are contacted through common friends, an approach that is particularly appropriate for the community under study.

Although rhotic assibilation in Mexican Spanish is a feature mainly observed in higher social classes, specifically mid-high to high class (Amastae et al. 1998; Perissinotto 1972), our study also includes participants of the mid-low or middle social classes. Most of the participants from El Paso who attend UTEP fall within the mid-low or middle social classes. The participants from the state of Chihuahua who attend UTEP are probably from mid to high classes, since it is very expensive for Mexican citizens to afford college north of the border. However, because we do not have an accurate tool to determine participants’ social class, we will not investigate the effect of this factor henceforth.

2.2. Independent Variables

Based on the literature reviewed, we investigated a number of linguistic and social factors considered significant in previous studies, in addition to other factors that proved important in our previous analysis of this feature (Mazzaro and González de Anda 2016). Among the linguistic factors, we analyzed the influence of the preceding context on the occurrence of assibilation. Mazzaro and González de Anda (2016) found that the distribution of rhotic assibilation across different vocalic contexts was different; [ř] was more frequent when preceded by [e] and [i]. Our 2016 study also confirmed previous findings that rhotic assibilation was localized to phrase-final position (Amastae et al. 1998; Lope Blanch 1967; Martín Butragueño 2006; Perissinotto 1972). Thus, we decided to focus our present study on this context only. Though our original plan was to study the influence of ‘stress’, we found very few tokens of syllable coda -r in unstressed position (N = 8) and, therefore, we could not investigate this effect.

Among the social factors, we analyzed the influence of sex, age, and education on the occurrence of rhotic assibilation. We also explored the effect of task: Reading (formal) vs. narrative of a fairy tale (semi-informal) vs. talking about the favorite food (informal) on the frequency of rhotic assibilation.

2.3. Data Collection and Recording Equipment

During the production stage of the study7, participants’ speech was elicited by completing three tasks. First, participants completed a word-list reading task (Appendix A). The stimuli were presented on a computer screen. Words from the list were presented one at a time using MS Power Point slides. For this task, participants were instructed to read words in isolation with a pause after each word. The stimuli consisted of 36 content words with a rhotic in final position and preceded by /a/, /e/, /i/, or /o/ e.g., comer (to eat); posar (to pose). The list contained 23 distracters, some of which had /r/ in different positions in the word or in consonant clusters e.g., bicho (bug); pared (wall). Word final rhotics were always in stressed syllables, so the ‘stress’ factor was not investigated in the word list.

In the second task, speakers narrated the fairy tale Caperucita Roja ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ fairy tale. To elicit the story, participants were shown wordless pictures of children’s book based on Perrault’s version of the tale. First, participants were shown the pictures as a refresher. When they felt ready, participants recorded the narrative using the images as guidance. The third production task consisted of an informal interview in which the researcher asked participants about their favorite food, where they eat it, and/or who prepares it. This last section was considered the most casual style of speech, since speakers were free to talk without prompts.

All the sessions were conducted in a sound-treated room. Informants were recorded directly onto a laptop computer using Audacity 2.1.2 and a Blue Snowball USB microphone. The speech was sampled at 44.1 K, and phrase-final rhotic tokens were analyzed with PRAAT (Boersma and Weenink 2018).

2.4. PRAAT and Spectrographic Inspection of Tokens

Recordings were transcribed with PRAAT (Boersma and Weenink 2018) using regular orthography on tier five (Figure 1). The transcriptions were force-aligned with Praatalign (Lubbers and Torreira 2016). After alignment, the text grids were manually inspected for accuracy. PraatAlign generated two tiers based on the audio and transcription: (1) The fourth tier contained the segmental analysis, and the third tier contained the word boundaries. The top tier contains our auditory classification of the rhotics in absolute final position, and the second tier contains the classification of the syllable into stress and unstressed. Our perception of rhotics was based on both auditory analysis and inspection of the spectrograms and oscillogram where necessary.

Figure 1.

Transcription of the narrative in PraatAlign. Female speaker (UT007).

2.5. Coding

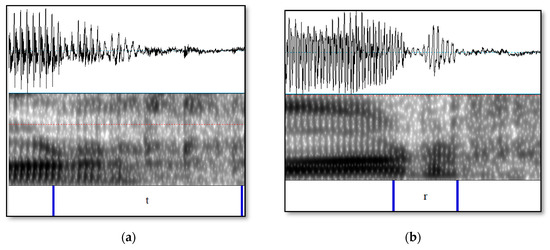

Rhotics in absolute final position were coded by two trained phoneticians who are Spanish speakers. Tokens were classified as either non-assibilated or assibilated. Non-assibilated tokens were coded as a trill (t) with multiple closures (Figure 2a) or as tap (r) with a single closure (Figure 2b). Assibilated rhotics (rs) were those where the presence of friction or noise was perceived strongly throughout the rhotic (Figure 1). Rhotics that were partially assibilated were coded as (m) ‘mix’ (Figure 2c). Mixed rhotics are those that begin with one or several closures (like a standard rhotic) and end with friction. If a token lacked closure and was accompanied by weak noise it was coded as (a) ‘approximant’ (Figure 2d). If the rhotic was heard as a trill (with several closures) with frication, it was coded as (ts) (Figure 2e). Rhotics that were heard as a voiced glottal fricative or aspiration, were coded as (h) (Figure 2f). Ambiguous or unintelligible tokens were classified as (n) and were later discussed with a third coder. Only the tokens for which there was complete agreement were included in the statistical analysis, so (n) tokens are excluded from the statistical analysis.

Figure 2.

(a) Trill (t) in the word dador (donor). Male speaker UT086; (b) tap (r) in the word sopor (sleepiness). Female speaker UT079; (c) partially assibilated (m) rhotic in the word besar (to kiss). Female speaker UT079; (d) approximant (a) in the word to weigh (pesar). Male speaker UT080; (e) assibilated trill (ts) in the word beber (to drink). Male speaker UT085; (f) aspirated rhotic (h) in the word tutor (tutor). Female speaker UT105.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

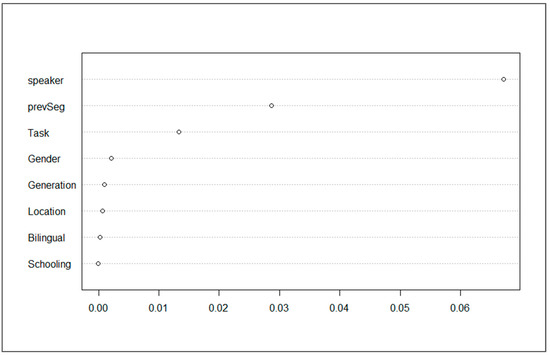

The effect of the linguistic and extra-linguistic variables was tested using binary logistic regression in R (R Core Team 2020). We used a mixed effect model that included ‘speaker’ as a random variable, using the lmer function (Bates et al. 2011). The independent variables were added to the regression model one at a time until the BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) for the model did not improve further. The order in which the variables were added to the model was determined by random forests, using the cforest and varimp functions in the party package also in R (Strobl et al. 2008). Random forests evaluate the relative importance of each independent variable, using a procedure that tests whether any independent variable is a sensitive predictor of the response variable. To do so, random forests follow a process of trial and error working with random samples of the data (Tagliamonte and Baayen 2012).

3. Results

The dataset consists of 2223 tokens of (r) in absolute final position. The word-list reading task yielded a total of 1762 tokens, the narrative task yielded a total of 235 tokens, and the semi-spontaneous speech yielded 226 tokens. The overall percentage of fully assibilated rhotics including all three tasks was 49.6% (N = 1103). However, as explained in the coding section, a thorough acoustic and perceptual analysis of the tokens showed that there were other more subtle rhotic variants with varying degrees of frication. In order to capture the difference in their realization and to provide a more accurate picture of assibilation in this speech community, we classified them according to their perceptual and acoustic characteristics. Table 2 presents the distribution of all /r/ variants in the three tasks combined.

Table 2.

Frequency of occurrence of all rhotic variants (three tasks combined).

Table 2 shows an overall low percentage of trills in absolute final position (4.9%) while taps are much more frequent in this position (38.3%). However, assibilated rhotics are by far the most common in absolute final position (49.6%), which is expected given that this is the favorable environment for this variant. The other non-standard variants were less frequent in our data: Partially assibilated rhotic 4%; approximant 2.2%; glottal fricative 0.7%; and assibilated trill 0.3%.

A closer look at the distribution of the data across factors can help us determine if there is any relationship between phonetic categories and the sociolinguistic dimensions investigated in this study. The following conditional inference tree (Figure 3) illustrates a link between gender and generation and their effect on the production of rhotic variants. A conditional inference tree allows the visualization of complex interactions between predictors. For each predictor, its influence in the outcome is tested. If the influence is statistically significant (low p-value), the data are split in two groups. The process repeats with each group until there are no more significant predictors. The resulting binary splits along with their respective p-values are plotted in a tree-like figure. The numbers in squares are the node numbers and only serve as a reference for identification. The ‘n’ number on each of the terminal nodes represent the number of data points in each group (see Tagliamonte and Baayen (2012) for a more detailed explanation of conditional inference trees).

Figure 3.

Conditional inference tree in R showing the distribution of phrase-final rhotic given gender and generation.

Figure 3 shows that assibilation (rs) is most frequent in female participants of generation 4 (older group). They record the highest levels of assibilation of all groups and the lowest rates of the standard variants: Trills (t) and taps (r). Because they have such high levels of assibilation, they also score a lower overall use of other non-standard variants such as partial assibilation (m), assibilated trills (ts), aspiration (h), and approximants (a). Middle-aged women (generations 2 and 3) present a low rate of assibilation and other non-standard variants in their speech, while they have a higher use of taps and trills. The difference between the middle-aged female groups and the younger one is that generation 1 has less assibilation overall and a more frequent occurrence of other variants such as approximants and partially assibilated rhotics. Their behavior resembles that of the younger male speakers who present a varied use of non-standard variants including assibilated and partially assibilated rhotics, approximants and aspiration. Males from generation 2 differ from generation 3 in their frequency of use of assibilation with generation 3 showing the lowest percentages of assibilation of all groups. In other words, females decrease their use of assibilation down the age scale while males increase their use of assibilation. In addition, while older females present an almost exclusive use of assibilated variants, younger females and males also use other non-standard and possibly less phonetically salient variants including partial assibilation, approximants, and aspiration.

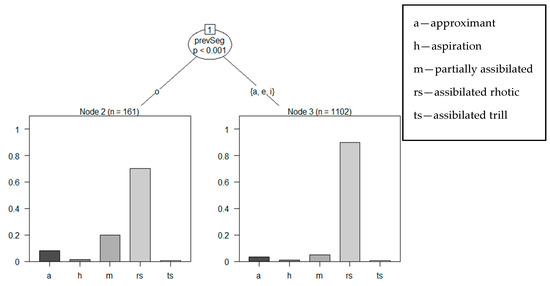

In the following conditional inference tree (Figure 4), we explore the relationship between preceding vowels (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/)8 and different rhotic variants to determine if certain patterns of distribution can be elucidated.

Figure 4.

Conditional inference tree in R showing the distribution of phrase-final rhotic given preceding vocalic context /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/.

Figure 4 shows that assibilated rhotics (rs) occur more frequently with /i/, /e/, and /a/, while /o/ presents a lower realization of assibilated rhotics and a higher percentage of partial assibilation and approximants.

Given the low overall percentage of partially assibilated rhotic, assibilated trills, approximants, and aspiration, we collapsed all these non-standard variants with assibilated rhotics for subsequent analysis and statistics. Taps and trills were collapsed into one group called standard variants. Table 3 shows the distribution standard vs. non-standard variants across the linguistic and extra-linguistic factors analyzed in this study. Factors are presented in order of importance as determined by the random forest analysis, which places the most important predictors at the top and the least important ones at the bottom (see page 14).

Table 3.

Distribution of standard and non-standard (r) across linguistic and social factor groups.

The analysis of preceding context shows a clear relationship between mid and high front vowels and assibilation (/i/ 79% and /e/ 64%). A preceding /a/ also has a high rate of assibilation (57%), but not as high as /e/ and /i/. On the contrary, the back vowel /o/ did not yield as much assibilation as the other vowels.

The overall percentage of assibilation including all three tasks was very high (56.86%). The distribution of assibilation by individual task shows that the top contributor of the high frequency of assibilation is the word-list reading task. Because the word list is considered a formal task, this result would suggest that assibilation is a prestigious feature of speech. However, the rates of assibilation in the other two tasks (narrative and conversation) appear to be contradictory, since the conversation has higher percentage of rhotic assibilation (43%) than the narrative (35%). A binary logistic regression analysis (Table 4) showed that while the difference between the reading task and the other two tasks was significant, there was no significant difference between the narrative and the conversation.

Table 4.

Binary logistic regression model coefficients with previous segment, task, and gender as predictors.

The next important predictor of assibilation is gender. Our study confirms what previous literature (Amastae et al. 1998; Lope Blanch 1967; Martín Butragueño 2006, 2014; Perissinotto 1972; Mazzaro and González de Anda 2016) has reported: Female speakers present a higher percentage of assibilated rhotics than males (65% vs. 43%). The significance of this and other factors was analyzed using a mixed effects binary logistic regression model in Table 4.

The next social factor in order of importance is ‘age’. The distribution of rhotic assibilation across generation groups presents an interesting effect with higher rates of the assibilated variant in the extreme groups (Gen1 60%; Gen2 51%; Gen3 49%; Gen4 83%). This pattern shows that assibilation is not receding, as reported by previous studies in Mexico City (Martín Butragueño 2006, 2014) and in Ciudad Juárez (Amastae et al. 1998). Figure 5 compares our percentages of assibilation per generation group with those of Amastae et al. (1998). Since Amastae et al. (1998) collected his data from sociolinguistic interviews, we compare their data with the conversation about favorite foods, which is the closest task in nature.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the distribution of rhotic assibilation across generation groups in Amastae et al. (1998) and our 2020 data.

The percentages of assibilation in the present have increased in all groups, especially in the youngest and the oldest. One reason that may account for the higher overall rates of assibilation in our data could be that our sample of participants also included Spanish speakers from the rest of the state of Chihuahua and El Paso, which have higher percentages of assibilation than speakers from Ciudad Juárez do. Besides overall percentages, it is important to examine what each generation is doing. Amastae et al.’s generation 3, which in 1998 had the highest proportion of assibilation, is now our generation 4, also with the highest rate of assibilation. It is important to point out that our generation 4 contains only female participants, which may also account for the apparent present day increase of assibilation in this particular generation, since female speakers are the most frequent users of assibilation. Amastae et al.’s generation 2, which in 1998 had the lowest percentage of assibilation, is now our generation 3, also with the lowest rate of assibilation. So, the higher peak and the lower dip have moved with the speakers, i.e., they have not remained static with the generation. The fact that assibilation is appearing in younger generations including males (as shown in Figure 3) may suggest that the variable is going through a revival process. However, the variability found is more complex than we had expected, because we discovered a vast array of variants co-occurring with the assibilated rhotic. Although an acoustic analysis would help elucidate this trend more accurately (Mazzaro forthcoming), our spectrographic examination of the tokens showed that the variant used by older women in generation 4 is more phonetically salient (higher concentration of noise and longer duration), whereas the variants used by younger people are more subtle and context dependent.

The effect of education is not very strong, as shown by small differences in percentages of assibilation in participants with university education (56%) and high school (60%). In fact, this was the last factor in order of importance listed by the random forest (Figure 6). We believe that the reason for the lack of effect in education could be that the participants in this study belonged to the two highest levels of education. Future studies should examine the influence of education on rhotic assibilation in participants with lower levels of formal education.

Figure 6.

Conditional permutation variable importance for the random forest with all predictors of rhotic assibilation.

The effect of bilingualism was analyzed despite the fact that our bilingual subjects are native Spanish speakers and received most of their formal education in Spanish. We wanted to make sure that the variation observed in our data was not the result of a cross-linguistic influence between English and Spanish. Thus, we compared bilingual speakers’ data with data collected from monolingual subjects. There was a higher rate of assibilation in bilinguals (63%) than in monolinguals (48%), but the random forest analysis gave this factor less weight after others were considered (Figure 6). In other words, although bilingual speakers had a higher percentage of assibilation in their speech, bilingualism does not seem to significantly influence the occurrence of the non-standard variant.

The distribution of assibilation across geographical areas is intriguing, especially because we find higher rates of assibilation in Chihuahua (capital and interior combined) than in Ciudad Juárez (69% and 51%, respectively), with El Paso somewhere in between (60%). We suspect that other factors could be interacting with location—age, for example. While the age distribution of the subjects from Chihuahua was fairly even, the subjects from El Paso and Ciudad Juárez were on average younger. As stated earlier, older speakers have higher rates of assibilation than all other groups, so having more older speakers may have inflated the percentages found in Chihuahua. The random forest analysis (Figure 6) shows that location is not a very strong predictor of assibilation once other factors are considered. Nevertheless, we believe that the influence of geographical space on the influence of rhotic assibilation should be re-examined with a more balanced distribution of subjects across geographical locations.

The random forest indicates that the most important predictor of rhotic assibilation is the individual speaker. This is due to the high degree of variability in the production of assibilated rhotics. For instance, in the narrative and the conversation, the rate of assibilation per individual ranged from 0% to 100%. Appendix B includes a table with number of tokens and percentage of assibilation per speaker in the narrative and the conversation combined.

Besides individual speakers, the next most important factors are preceding context, task, gender, generation, location, bilingualism, and education. The influence of each of these factors on the occurrence of the variable under study has been discussed above.

Finally, we conducted several mixed-effects binomial logistic regression models fitted to the data to determine the most important predictors. Factors were added one at a time, until the model did not improve anymore. Table 4 shows that beyond the individual speaker, the most decisive predictors of rhotic assibilation are: Previous segment, task, and gender with an interaction with generation.

The binary logistic regression model shows that preceding context, especially /i/, favors rhotic assibilation. A following /e/ is also a favoring environment for assibilation to occur. However, a preceding /o/ disfavors the occurrence of assibilation. These preceding contexts were compared to the reference vowel /a/. The next factor that predicted assibilation was task, particularly the word list, which promotes assibilation compared to the reference narrative. The conversation is not significantly different from the narrative. Gender and generation are not shown as significant predictors by themselves; however, their interaction proves to be significant. The coefficient estimate shows that the older male speakers disfavor assibilation. In addition, we know from the conditional inference tree (Figure 2) that older females have the highest rates of assibilation from all groups.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study was designed to explore different aspects of the variation affecting rhotics in phrase-final position in the Chihuahua/El Paso speech community. In this section, we address the questions posed at the beginning of the study.

The first question concerned the current state of rhotic assibilation in Chihuahua Spanish. We compared our study with Amastae et al.’s (1998) and contrary to our expectations, we found that rhotic assibilation is not receding, but it is quite frequent in the population and, particularly, in the younger groups of both genders. In general, assibilation continues to be more prevalent amongst females, but male speakers assibilate, too. In fact, as the title of this study suggests, we consider the frequency of assibilation in male speakers a sign that the variable is losing its feminine connotation and becoming a variant available across genders. So, if assibilation is not receding, are we seeing a revival of the assibilated rhotic imported from Mexico City in the 1960s (Amastae et al. 1998)? We argue that the variation adopted by the younger groups seems to have lost its social connection with femininity and sophistication; i.e., it may not be the same as the original variant from the 1960s. As shown by the present results, young speakers of both genders use the fully assibilated rhotic, but younger males are also using a more diverse set of variants, which are more ‘subtle’ (less salient) than the fully assibilated rhotic. Although we are currently working on the results of the acoustic analysis to confirm this statement (Mazzaro forthcoming), we observed that the variants that alternate with the fully assibilated rhotic (partially assibilated rhotic, approximants, glottal fricatives, assibilated trills) have shorter durations and lower intensity than the fully assibilated one.

We speculate that there is a closer connection between the fully assibilated rhotics found in older females and the variable imported from Mexico City, while the variation found in younger generations is more phonetically motivated. There might be a socio-economic explanation for the difference between the variation found in younger and older groups. Ciudad Juárez has been considered a place of opportunity due to the many jobs created by international companies and factories (known as maquiladoras) that boomed in the 1990s, when NAFTA was approved. Since the year 2000, immigration rates to the city increased considerably as a result of the arrival of immigrants from other regions (Cruz 2012) looking for work. The improved economic situation of the people from Ciudad Juárez vis-à-vis the rest of the country, may have increased the local pride in being from Ciudad Juárez, which may favor the adoption of local features of speech, rather than linguistic innovations from abroad.

Our second question concerned the type of rhotic variants found in Chihuahua Spanish. We based our analysis on a combination of auditory transcription and spectrographic inspection of tokens. As hypothesized, the standard variants (taps and trills) are the most frequently used variants across participants. Besides the standard rhotics, we identified five non-standard variants: Assibilated rhotics, approximants, partially assibilated rhotics, aspiration, and assibilated trills; the last three variants had not been initially anticipated. We explored whether these variants were also influenced by social factors, as the fully assibilated rhotic was. As already mentioned, we found that while older females preferred the fully assibilated variant, younger generations, and particularly men, had a wider variety of variants in their speech. The results presented here confirm what Tagliamonte (2011) suggested, “everyone marks their place in the social hierarchy in phonetically distinguishable ways.”

Our third question explored the most important linguistic and social correlates of rhotic assibilation. Our analysis based on random forest and binary logistic regression models indicated that beyond the individual speaker, which is the highest source of variability in the data, the preceding context is the most important factor influencing the variable under study. A preceding /i/ and /e/ significantly favored the occurrence of rhotic assibilation. Conversely, a preceding /o/ disfavored assibilation and had a wider range of variants co-occurring with it. We believe that the highest rate of assibilation next to /i/ and /e/ could be explained in articulatory terms. To produce /i/ and /e/ the dorsum of the tongue moves up and toward the front. However, to realize a trill or a tap the position of the tongue root retracts towards the back of the oral cavity, and the tongue body adopts a hollow or concave shape that allows the tongue tip to cup towards the alveolar ridge to produce a brief contact (tap). Because the position of a high-front vowel requires the tongue dorsum and root to go up, while the trill or tap requires the tongue root to stay down and retract, the co-articulation between these two sounds may cause modifications in the production of the rhotic. According to Solé (2002) small changes in aerodynamic conditions that govern the production of the trill may result in a fricative sound. The fact that assibilation is more common in phrase-final position can also be phonetically motivated, as it results from the difficulty of sustaining trilling with the lowered decreased subglottal pressure that occurs at the end of a statement (Solé 2002).

With regard to the most important social correlates of rhotic assibilation, we confirmed our hypothesis that gender and age would significantly affect the variant under study. Concerning gender, our results agreed with those of previous studies that females favor assibilation more than males. In reference to age, we found that older female speakers tend to produce more assibilated rhotics that the other groups. However, the finding that youngest female and male speakers also had high percentages of assibilation was not anticipated by our hypothesis.

The fourth question examines whether language contact with English affected the occurrence of this variable in bilingual speech. The random forest analysis placed the ‘bilingualism’ factor in penultimate position, showing that it was one of the least important factors affecting rhotic assibilation. In addition, the binary logistic regression model stopped improving before adding this predictor. Our hypothesis was confirmed, as we did not find a significant difference in the rate of production of rhotic assibilation in bilinguals compared to monolinguals. A future study exploring how the other factors impinge on the realization of assibilated rhotics across bilingual vs. monolingual groups could help us understand finer grained differences depending on sociophonetic competence.

Concerning the effect of style (reading vs. narrative vs. conversation) on the occurrence of assibilation, we found that the more formal reading task (word list) favored assibilation compared to the narrative and the conversation9. However, there was no significant difference in rate of assibilation between the narrative and the conversation. This was an interesting finding, as we expected the assibilation rate to be higher in the narrative, which was considered more formal than the conversation. In other words, style seems to play a role when comparing reading vs. other tasks, but there does not seem to be a special sensitivity of participants to the difference between the narrative and the conversation. One possibility could be that speakers did not consider the narrative with visual prompts more formal than chatting about their favorite food. Another possibility could be related to the low perception and sociolinguistic awareness of rhotic assibilation in this population (Mazzaro and González de Anda 2019). Since rhotic assibilation seems to be below the level of consciousness and social awareness, we would not expect a high degree stylistic shift within the more casual tasks.

The final question concerns the status of assibilation as a prestigious feature of speech. The significantly higher rate of assibilation in the formal reading task suggests that rhotic assibilation continues to be a prestigious feature, as stated in our hypothesis. In addition, we found women to be ahead of men in the use of rhotic assibilation, which supports the sociolinguistic principle proposed by Labov (2001) that in changes from below the level of consciousness awareness, women tend to lead men in their use of prestigious variants. However, in order to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the status of rhotic assibilation in Chihuahua Spanish, we need to supply this analysis with information about social class. When talking about gender differentiation, Labov (2001) argued that the behavior of women is far from uniform across the speech community and that there is an intimate and complex interaction between style, gender, and social class. The results of this study clearly show that women are the leaders of this linguistic change, but it also demonstrates that younger men are adopting the change. We find men’s use of a wider set of variants particularly intriguing and, as stated earlier, we need to examine whether they have achieved the status of sociolinguistic variants and the social meanings they contain.

To conclude, the purpose of this study was to examine the current state of rhotic assibilation in Chihuahua Spanish two decades after Amastae et al. (1998) conducted the first study. The results of our analysis reveal that the feature is frequent among the youngest groups and it does not show signs of disappearing as previously stated (Amastae et al. 1998; Martín Butragueño 2006; Perissinotto 1972). On the contrary, our study found much higher rates of rhotic assibilation than Amastae et al. did in 1998, both overall and across age groups.

Despite the high degree of variability across individual speakers, we found that specific linguistic (preceding context) and extra-linguistic factors (style, gender, and generation) are strong predictors of the variable in question. Rhotic assibilation is phonetically motivated by phrase-final position and preceding non-low front vowels /i/ and /e/, which cause the tongue body to move up and front making it more difficult to sustain trilling. As stated earlier, the production of a trill requires fine articulatory and aerodynamic conditions that are highly sensitive to contextual and prosodic conditions. Imperfect articulatory positioning and changing aerodynamic conditions can lead to acoustic variations that provide favorable grounds for assibilation to occur. An interesting finding of this study is that the variation does not entail a simple binary opposition between assibilated and non-assibilated rhotic, but that the variable involves a more complex array of variants (partially assibilated rhotics, approximants, glottal fricatives, assibilated trills). Interestingly, men are the main users of these variants, which we speculate are less salient (or weaker) forms of rhotic assibilation. The next step of this investigation is to conduct an acoustic analysis of these fine-grained, sub-phonemic variations in pronunciation and to determine whether they have social meaning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M. and R.G.; Data curation, N.M. and R.G.; Investigation, N.M. and R.G.; Methodology, N.M. and R.G.; Project administration, N.M. and R.G.; Resources, N.M.; Supervision, N.M.; Writing—original draft, N.M.; Writing—review & editing, R.G. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Martin Lazzari for his help with the statistical analysis, Laura Colantoni, Jon Amastae and Richard Teschner for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We wish to express our appreciation to two anonymous reviewers for their thorough review of this paper and their clever recommendations. Last, but not least, a big thank you to all the participants in this study. Errors and omissions are entirely our responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Stimuli used were content words with a rhotic in coda final position and preceded by /a/, /e/, /i/, or /o/:

Bazar, billar, dejar, besar, guerrear, guisar, gozar, beber, duchar, poder, datar, gustar, pedir, podar, dador, pagar, seguir, donar, botar, casar, pasar, pesar, pitar, posar, telar, tirar, tocar, quemar, copar, sopor, sentir, sacar, curar, tutor, pudor, ayer.

Distracters (inserted randomly between the words listed above):

Bicho, cerro, arresta, es hembra, es cebra, pared, horrendo, cero, paré, reza, resta, red, renta, cerca, drogui, círculo, terso, dicho, tribu, tropel, virtud, champú, cura.

Appendix B

Number of tokens with rhotics in phrase-final position, realized as standard rhotic (tap or tril), assibilated and percentage of rhotic assibilation per individual subject.

Table A1.

Number and percentage of realizations of the standard and assibilated by individual speaker.

Table A1.

Number and percentage of realizations of the standard and assibilated by individual speaker.

| Speaker | Number of Tokens | Standard | Assibilated | Percent Assibilation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UT007 | 21 | 9 | 12 | 57.1% |

| UT030 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 66.7% |

| UT032 | 24 | 24 | 0 | 0.0% |

| UT034 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 60.0% |

| UT035 | 13 | 11 | 2 | 15.4% |

| UT036 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 50.0% |

| UT037 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 33.3% |

| UT038 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 40.0% |

| UT039 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 12.5% |

| UT040 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 50.0% |

| UT041 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 20.0% |

| UT060 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50.0% |

| UT061 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 55.6% |

| UT062 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 30.0% |

| UT067 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 40.0% |

| UT070 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0.0% |

| UT072 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 20.0% |

| UT073 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 25.0% |

| UT074 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 37.5% |

| UT076 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.0% |

| UT077 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 33.3% |

| UT079 | 16 | 5 | 11 | 68.8% |

| UT080 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50.0% |

| UT081 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 100.0% |

| UT082 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 100.0% |

| UT083 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 55.6% |

| UT084 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 37.5% |

| UT085 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0.0% |

| UT086 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 33.3% |

| UT087 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0.0% |

| UT088 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 20.0% |

| UT089 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 50.0% |

| UT090 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 33.3% |

| UT091 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3% |

| UT092 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 66.7% |

| UT093 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 55.6% |

| UT094 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 14.3% |

| UT096 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 20.0% |

| UT097 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 71.4% |

| UT098 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 66.7% |

| UT099 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 20.0% |

| UT100 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 100.0% |

| UT101 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 33.3% |

| UT102 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 55.6% |

| UT103 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50.0% |

| UT104 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0.0% |

| UT105 | 17 | 10 | 7 | 41.2% |

| UT106 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 66.7% |

| UT107 | 15 | 12 | 3 | 20.0% |

| UT108 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 100.0% |

| UTCJ1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 66.7% |

| UTCJ3 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 45.5% |

| UTCJ4 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 14.3% |

| UTCJ5 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 72.7% |

| UTCJ6 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 25.0% |

| UTCJ7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 20.0% |

| UTCJ8 | 17 | 12 | 5 | 29.4% |

| Total | 461 | 282 | 179 | 38.8% |

References

- Amastae, Jon, Alberto Escalera, Araceli Arceo, Zenia Gutiérrez, Homero Silva, and Bertha Talamantes. 1998. Cambio desde abajo, cambio desde arriba. Memorias del IV Encuentrio Internacional de Linguistica en el Noroeste 2: 269–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, and Ben Bolker. 2011. Lme4: Linear Mixed-Effect Models Using S4 Classes. R Package Version 0.999375-42. Available online: http//CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Blecua, Beatriz, and Jordi Cicres. 2019. Rhotic variation in Spanish codas: Acoustic analysis and effects of context in spontaneous speech. In Romance Phonetics and Phonology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2018. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program]. Version 6.0.43. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Bradley, Travis G. 2004. Gestural timing and rhotic variation in Spanish. In Laboratory approaches to Spanish phonology 7: 195. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Travis G., and Erik W. Willis. 2012. Rhotic variation and contrast in Veracruz Mexican Spanish. Estudios De Fonética Experimental 21: 43–74. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield, D. Lincoln. 1981. Spanish Pronunciation in the Americas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza, Luz Marina Vásquez. 2006. On the Phonetic Realization and Distribution of Costa Rican Rhotics. Revista De Filología y Lingüística De La Universidad De Costa Rica Vol.32 Núm.2 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315716488_On_the_phonetic_realization_and_distribution_of_Costa_Rican_rhotics (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Colantoni, Laura Marcela. 2001. Mergers, Chain Shifts and Dissimilatory Processes: Palatals and Rhotics in Argentine Spanish. Master’s dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Colantoni, Laura. 2006. Increasing periodicity to reduce similarity: An acoustic account of deassibilation in rhotics. Paper presented at the 2nd Conference on Laboratory Approaches to Spanish Phonetics and Phonology, Somerville, MA, USA, September 17–19; pp. 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, Rodolfo. 2012. Cambios fronterizos y movimientos migratorios en la frontera norte de México. In México ante los Recientes Desafíos de la Migración Internacional Mexico City. Edited by T. Ramírez García and M. Ángel Castillo. Mexico City: Consejo Nacional de Población, pp. 157–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dalola, Amanda, and Barbara E. Bullock. 2017. On Sociophonetic Competence: Phrase-final Vowel Devoicing in Native and Advanced L2 Speakers of French. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 39: 769–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, Wendianne Alice. 2013. Sociolingüística del Español gay Mexicano: Variación Fónica, Estereotipos, Creencias y Actitudes en una Red Social de Hombres Homosexuales. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, Nicholas C., and Erik W. Willis. 2010. Acoustic characterization of phonemic trill production in Jerezano Andalusian Spanish. Paper presented at the 4th Conference on Laboratory Approaches to Spanish Phonology, Somerville, MA, USA, January 1; pp. 115–27. [Google Scholar]

- Howson, Phil, Ekaterina Komova, and Bryan Gick. 2014. Czech trills revisited: An ultrasound EGG and acoustic study. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 44: 115–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hualde, José Ignacio. 2005. The Sounds of Spanish with Audio CD. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 2001. Principles of Linguistic Change Volume 2: Social Factors. Language in Society. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Ladefoged, Peter, and Ian Maddieson. 1996. The Sounds of the World’s Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John M. 1994. Latin American Spanish. Boston: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Lope Blanch, Juan M. 1967. La influencia del sustrato en la fonética del español de México. Revista De Filología Española 50: 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, Mart, and Francisco Torreira. 2016. Praatalign: An Interactive Praat Plug-in for Performing Phonetic Forced Alignment. A Detailed Manual for Version 1.8. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/399059498/Praat-Plugin-Book-2-0 (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Martín Butragueño, Pedro. 2006. Líderes lingüísticos en la Ciudad de México. In Líderes Lingüísticos: Estudios De Variación y Cambio. Mexico City: El Colegio De México, pp. 158–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Butragueño, Pedro. 2014. Fonología Variable del Español de México. México City: El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaro, Natalia. Forthcoming. Men are doing it differently: Acoustic analysis of rhotic assibilation in Chihuahua Spanish.

- Mazzaro, Natalia, and Raquel González de Anda. 2016. A receding variation: Rhotic assibilation in Chihuahua Spanish. In Hispanic Linguistic Symposium 2016. Washington, DC: Georgetown University. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaro, Natalia, and Raquel González de Anda. 2019. The perception-production connection: /tʃ/ deaffrication and rhotic assibilation in Chihuahua Spanish. In Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics series: Recent Advances in the Study of Spanish Sociophonetic Perception. Edited by Whitney Chappell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Milroy, Lesley. 1987. Language and Social Networks. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Terrell A., and Sandro Sessarego. 2016. A phonetic analysis of intervocalic /r/ in highland Bolivian Spanish. Spanish in Context 13: 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissinotto, Giorgio S. A. 1972. Distribución demográfica de la asibilación de vibrantes en el habla de la ciudad de México. Nueva Revista De Filología Hispánica 21: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilis, Antonio. 1981. Fonética Acústica de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Quilis, Antonio. 1993. Tratado de Fonología y Fonética Españolas. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Rissel, Dorothy A. 1989. Sex, attitudes, and the assibilation of /r/ among young people in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Language Variation and Change 1: 269–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Adelaide Hercilia Pescatori. 1996. Para a Descriçao Fonético-Acústica das Líquidas no Português Brasileiro: Dados de um Informante Paulistano. Master’s dissertation, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, Maria-Josep. 1992. Experimental phonology: The case of rhotacism. Phonologica 1988: 259–71. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, Maria-Josep. 2002. Aerodynamic characteristics of trills and phonological patterning. Journal of Phonetics 30: 655–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, Carolin, Boulesteix Anne-Laure, T. Kneib, Augustin Thomas, and Zeileis Achim. 2008. Conditional Variable Importance for Random Forests. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 307. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471–2105/9/307 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2011. Variationist Sociolinguistics: Change, Observation, Interpretation. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali A., and R. Harald Baayen. 2012. Models, forests and trees of York English: Was/were variation as a case study for statistical practice. Language Variation and Change 24: 135–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, Tomás Navarro. 1970. Manual de Pronunciación Española. Madrid: CSIC. First published 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Erik W. 2007. An acoustic study of the ‘pre-aspirated trill’ in narrative Cibaeño Dominican Spanish. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 37: 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The distribution of trills and taps is further discussed in Hualde (2005). |

| 2 | Since there is variation affecting the system of rhotics (Hualde 2005), when we refer to ‘standard’ variants we mean prestige forms used in careful speech, prescribed by schools and used by newscasters. |

| 3 | Lipski (1994) and Hualde (2005) discussed other (non-standard) realizations including dorsalization and pre-aspiration of the trill, neutralization, retroflexion, strengthening of rhotics in codas and onset clusters. |

| 4 | Solé (1992) actually refers to word-final rhotics as “trills” but, as stated earlier, we prefer to use Hualde’s (2005) neutral term “rhotic”. Solé also refers to assibilated variants as “fricatives”. |

| 5 | Amastae et al. (1998) did not analyze the speech of participants of lower socio-economic class. |

| 6 | We consider El Paso, TX part of the state of Chihuahua’s Spanish-language speech community because of their geographic proximity (separated only by the Rio Grande River). We are aware that there is lack of research that compares the Spanish of the state of Chihuahua and that of El Paso, but we posit that they are one dialect, at least at the phonetic/phonological level. |

| 7 | Participants also performed a perception task. This study focuses on the production data only. The perception study was published elsewhere (Mazzaro and González de Anda 2019). |

| 8 | Because only 3 tokens with a preceding /u/ were found in narrative and the informal speech (sur ‘south’ appeared twice and tour once), these tokens were excluded from analysis. |

| 9 | One of the reviewers suggested that reading differs in many ways from the other tasks, in that it involves other cognitive processes and makes subjects focus more on pronunciation because of the lack of content. In other words, the difference between the reading task and the other two tasks could be due to the formality plus the additional cognitive processes involved in reading. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).