Animation in Speech, Language, and Communication Assessment of Children: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Approaches to Animation

1.2. Research Involving Animation in Speech–Language Pathology

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Method

“What studies have utilized animations to assess children with speech, language, or communication deficits and/or disorders?”

- (a)

- What theoretical or research foundations supported the use of animation?

- (b)

- What was the purpose of using animation?

- (c)

- In what form were animations utilized?

- (d)

- What skills were the tools or tasks designed to assess?

- (e)

- Which clinical populations were they developed for?

- (f)

- What were the technical features of the animations?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection of Evidence Sources

2.5. Data Charting

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. Research Aims and Animations

4. Discussion

- (a)

- What theoretical or research foundations supported the use of animation?

- (b) What was the purpose of using animation?

- (c) In what form were animations utilized?

- (d) What skills were the tools or tasks designed to assess?

- (e) Which clinical populations were they developed for?

- (f) What were the technical features of the animations?

4.1. Evidence Base for Animation in Speech–Language Pathology Assessment

4.1.1. Research Approaches

- (a)

- Experimental studies that directly compared animated and static representations reported mixed findings, with some showing comparable performance across modalities (Klop & Engelbrecht, 2013) and others demonstrating improved performance with animation for specific language tasks (Frizelle et al., 2018a; Diehm et al., 2020).

- (b)

- Studies that supported the use of animation based on prior literature or experimental research (Puolakanaho et al., 2004; Bishop et al., 2009; McGonigle-Chalmers et al., 2013; Badcock et al., 2018; Krok et al., 2022; Jackson et al., 2023; Lloyd-Esenkaya et al., 2024).

- (c)

- Studies that, while using animation to meet specific research objectives, provided valuable insights into responses/behaviors of children on animation (Gazella & Stockman, 2003; Alt, 2013; Polišenská & Kapalková, 2014; Petit et al., 2020b; Hodges et al., 2017).

- (d)

- Standardization studies of language assessment measures that used animated items with large research samples (De Villiers et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2023).

- (e)

- Studies applying animated tasks in children with language disorders, providing evidence from atypical language development (Pace et al., 2022; Frizelle et al., 2018b; Lloyd-Esenkaya et al., 2024).

4.1.2. Animation and Language

4.1.3. Motivation, Engagement, and Participation

4.1.4. Data from Clinical Samples

4.1.5. Animation and Cognition

4.1.6. Psychometric Properties

4.2. Limitations and Gaps of Knowledge

4.3. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLP | Speech–language pathologist |

| AAC | Augmentative and Alternative Communication |

| TD | Typically developing |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| PPC | Population, Concept, and Context |

| ToM | Theory of Mind |

| fTCD | Functional transcranial Doppler ultrasonography |

| SLI | Specific language impairment |

| DS | Down syndrome |

| DLD | Developmental language disorder |

| QUILS | Quick Interactive Language Screener |

| QUILS: ES | Quick Interactive Language Screener: English–Spanish |

| QUILS: TOD | Quick Interactive Language Screener: Toddlers |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| N/A | Not applicable |

Appendix A

| Section | Item | PRISMA-ScR Checklist Item | Reported on Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 1, 2, 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 4 |

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | N/A |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status) and provide a rationale. | 5 and Table 1 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 5 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 5 and Table 2 |

| Selection of sources of evidence process | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 5 and Table 1 |

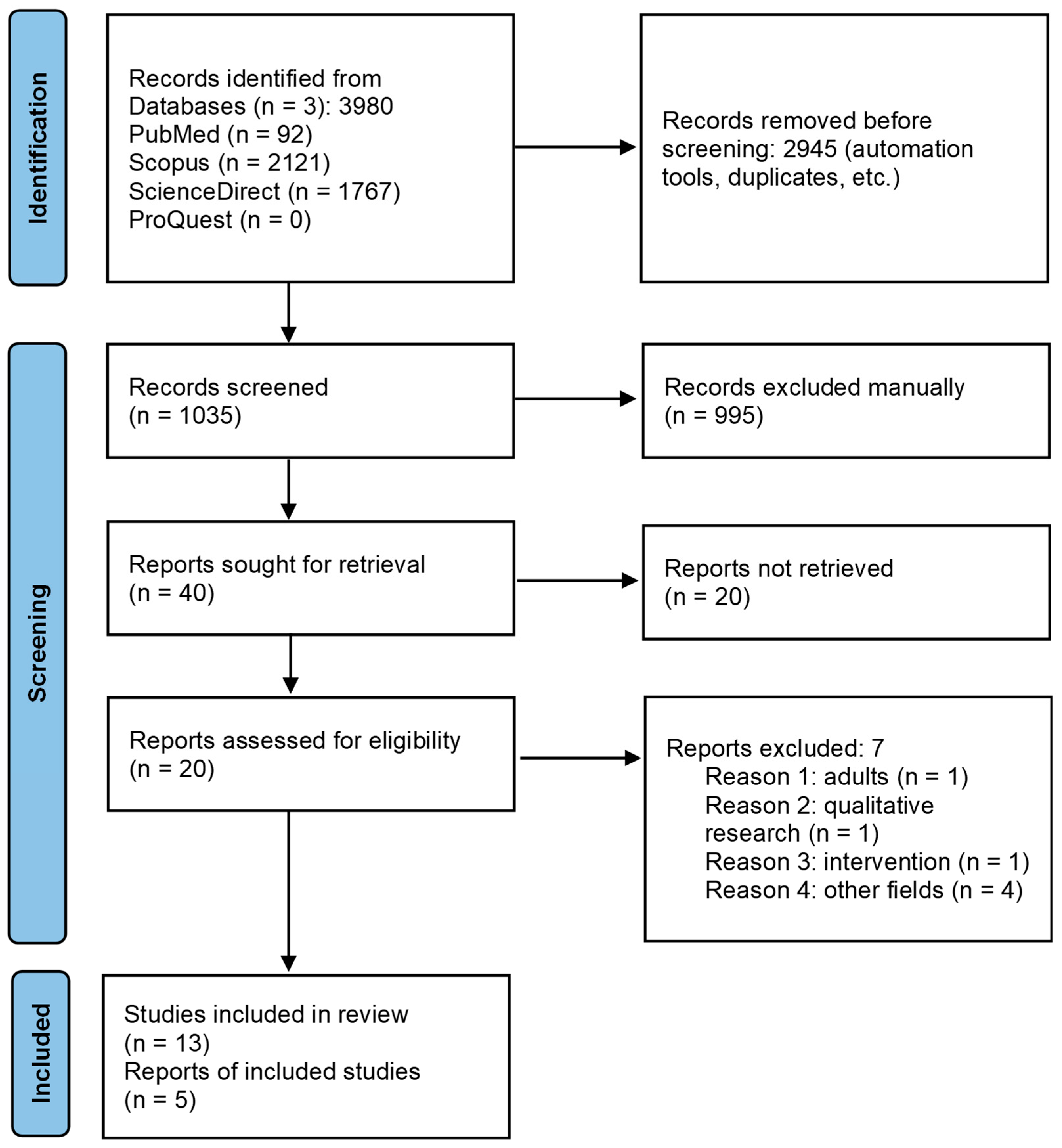

| Selection of sources of evidence | 10 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 5, 6, and Figure 1 |

| Data charting process | 11 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was performed independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 7 |

| Data items | 12 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 7 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence | 13 | If performed, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | N/A |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | Table 3 and Table 4 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 15 to 18 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If performed, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | N/A |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 15 to 18 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 19, 20 |

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 20 to 22 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 22 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 23 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | N/A |

References

- Alt, M. (2013). Visual fast mapping in school-aged children with specific language impairment. Topics in Language Disorders, 33(4), 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badcock, N. A., Spooner, R., Hofmann, J., Flitton, A., Elliott, S., Kurylowicz, L., Lavrencic, L. M., Payne, H. P., Holt, G. H., Holden, A., Churches, O. F., Kohler, M. J., & Keage, H. A. (2018). What box: A task for assessing language lateralization in young children. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition, 23(4), 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berney, S., & Bétrancourt, M. (2016). Does animation enhance learning? A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 101, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betrancourt, M., & Tversky, B. (2000). Effect of computer animation on users’ performance: A review (Effet de l’animation sur les performances des utilisateurs: Une sythèse). Le Travail Humain, 63(4), 311–329. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/effect-computer-animation-on-users-performance/docview/1311633511/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Bishop, D. V., Watt, H., & Papadatou-Pastou, M. (2009). An efficient and reliable method for measuring cerebral lateralization during speech with functional transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Neuropsychologia, 47(2), 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, K. L., Zolkoske, J., Cummings, A., & Ogiela, D. A. (2022). The effects of symbol format and psycholinguistic features on receptive syntax outcomes of children without disability. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(12), 4741–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E. J., Williams, D. L., Hodgins, J. K., & Lehman, J. F. (2014). Are children with autism more responsive to animated characters? A study of interactions with humans and human-controlled avatars. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2475–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, N., Shane, H., Schlosser, R. W., Haynes, C. W., & Allen, A. (2022). Directive-following based on graphic symbol sentences involving an animated verb symbol: An exploratory study. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 43(3), 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, J., Iglesias, A., Golinkoff, R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Wilson, M. S., & Nandakumar, R. (2021). Assessing dual language learners of Spanish and English: Development of the QUILS: ES. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología, 41(4), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehm, A. E., Wood, C., Puhlman, J., & Callendar, M. (2020). Young children’s narrative retell in response to static and animated stories. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(3), 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollaghan, A. C. (2008). The handbook for evidence-based practice in communication disorders. Paul H. Brookers Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, S. M. (2006). Twelve steps for effective test development. In S. M. Downing, & T. M. Haladyna (Eds.), Handbook of test development (pp. 3–25). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folksman, D., Fergus, P., Al-Jumeily, D., & Carter, C. (2013, December 16–18). A mobile multimedia application inspired by a spaced repetition algorithm for assistance with speech and language therapy. 2013 Sixth International Conference on Developments in Esystems Engineering (pp. 367–375), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J. A., & Milosky, L. M. (2008). Inference generation during discourse and its relation to social competence: An online investigation of abilities of children with and without language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(2), 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, B., Boster, J. B., & Thompson, S. (2022). Animation in AAC: Previous research, a sample of current availability in the United States, and future research potential. Assistive Technology, 35, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizelle, P., Thompson, P., Duta, M., & Bishop, D. V. (2018a). Assessing children’s understanding of complex syntax: A comparison of two methods. Language Learning, 69(2), 255–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizelle, P., Thompson, P. A., Duta, M., & Bishop, D. V. (2018b). The understanding of complex syntax in children with down syndrome. Wellcome Open Research, 3, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, K., Inoue, T., Yamana, Y., & Hayashi, H. (2011). The effect of animation on learning action symbols by individuals with intellectual disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazella, J., & Stockman, I. J. (2003). Children’s story retelling under different modality and task conditions. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glascoe, F. P., & Cairney, J. (2018). Best practices in test construction for developmental-behavioral measures: Quality standards for reviewers and researchers. In H. Needelman, & B. J. Jackson (Eds.), Follow-up for NICU graduates: Promoting positive developmental and behavioral outcomes for at-risk infants (pp. 255–279). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinkoff, R. M., De Villiers, J. G., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Iglesias, A., Wilson, M. S., Morini, G., & Brezack, N. (2017). User’s manual for the quick interactive language screener (QUILS): A measure of vocabulary, syntax, and language acquisition skills in young children. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, A. C., Schlosser, R. W., Gygi, B., Shane, H. C., Kong, Y. Y., Book, L., Macduff, K., & Hearn, E. (2014). Effects of environmental sounds on the guessability of animated graphic symbols. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30(4), 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetzroni, O. E., & Tannous, J. (2004). Effects of a computer-based intervention program on the communicative functions of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, R., Munro, N., Baker, E., McGregor, K., & Heard, R. (2017). The monosyllable imitation test for toddlers: Influence of stimulus characteristics on imitation, compliance and diagnostic accuracy. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52(1), 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S., McDermott, E., Reilly, K., & Arunachalam, S. (2018). Acquisition of verb meaning from syntactic distribution in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(3S), 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, L., McCarthy, J. W., Roth, M. A., & Marinellie, S. A. (2014). The effects of an animated exemplar/nonexemplar program to teach the relational concept on to children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental delays who require AAC. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 41, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höffler, T. N., & Leutner, D. (2007). Instructional animation versus static pictures: A meta-analysis. Learning and Instruction, 17(6), 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, A., De Villiers, J., Golinkoff, R. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Wilson, M. S. (2021). User’s manual for the quick interactive language screener–ES™ (QUILS–ES™): A measure of vocabulary, syntax, and language acquisition skills in young bilingual children (Version ES). Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, E., Levine, D., de Villiers, J., Iglesias, A., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Michnick Golinkoff, R. (2023). Assessing the language of 2 year-olds: From theory to practice. Infancy, 28(5), 930–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagaroo, V., & Wilkinson, K. (2008). Further considerations of visual cognitive neuroscience in aided AAC: The potential role of motion perception systems in maximizing design display. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24(1), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klop, D., & Engelbrecht, L. (2013). The effect of two different visual presentation modalities on the narratives of mainstream grade 3 children. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 60(1), 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, W., & Leonard, L. B. (2018). Verb variability and morphosyntactic priming with typically developing 2-and 3-year-olds. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(12), 2996–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, W., Norton, E. S., Buchheit, M. K., Harriott, E. M., Wakschlag, L., & Hadley, P. A. (2022). Using animated action scenes to remotely assess sentence diversity in toddlers. Topics in Language Disorders, 42(2), 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., & Hong, K. H. (2013). The effect of animations on the AAC symbol recognition of children with intellectual disabilities. Special Education Research, 12(2), 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Esenkaya, V., Russell, A. J., & St Clair, M. C. (2024). Zoti’s Social Toolkit: Developing and piloting novel animated tasks to assess emotional understanding and conflict resolution skills in childhood. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, R., & Boucheix, J.-M. (2017). A composition approach to design of educational animations. In R. Lowe, & R. Ploetzner (Eds.), Learning from dynamic visualization: Innovations in research and application (pp. 5–30). Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-56204-9 (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Massaro, D. W., & Bosseler, A. (2006). Read my lips: The importance of the face in a computer-animated tutor for vocabulary learning by children with autism. Autism, 10(5), 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaro, D. W., & Light, J. (2004). Improving the vocabulary of children with hearing loss. Work, 831, 459–2330. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2002). Animation as an aid to multimedia learning. Educational Psychology Review, 14, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. W., & Boster, J. B. (2018). A comparison of the performance of 2.5 to 3.5-year-old children without disabilities using animated and cursor-based scanning in a contextual scene. Assistive Technology, 30(4), 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigle, B., & Chalmers, M. (2002). A behavior-based fractionation of cognitive competence with clinical applications: A comparative approach. International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 15, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigle-Chalmers, M., Alderson-Day, B., Fleming, J., & Monsen, K. (2013). Profound expressive language impairment in low functioning children with autism: An investigation of syntactic awareness using a computerised learning task. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2062–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineo, B. A., Peischl, D., & Pennington, C. (2008). Moving targets: The effect of animation on identification of action word representations. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24(2), 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, R., Pete, A. M., & Popeson, J. (2008). Using animated language software with children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 4(6), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nealis, P. M., Harlow, H. F., & Suomi, S. J. (1977). The effects of stimulus movement on discrimination learning by rhesus monkeys. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 10(3), 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, A., Curran, M., Van Horne, A. O., de Villiers, J., Iglesias, A., Golinkoff, R. M., Wilson, M. S., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2022). Classification accuracy of the quick interactive language screener for preschool children with and without developmental language disorder. Journal of Communication Disorders, 100, 106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, S., Badcock, N. A., Grootswagers, T., Rich, A. N., Brock, J., Nickels, L., Moerel, D., Dermody, N., Yau, S., Schmidt, E., & Woolgar, A. (2020a). Toward an individualized neural assessment of receptive language in children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(7), 2361–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, S., Badcock, N. A., Grootswagers, T., & Woolgar, A. (2020b). Unconstrained multivariate EEG decoding can help detect lexical-semantic processing in individual children. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 10849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploetzner, R., Berney, S., & Bétrancourt, M. (2020). A review of learning demands in instructional animations: The educational effectiveness of animations unfolds if the features of change need to be learned. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(6), 838–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polišenská, K., & Kapalková, S. (2014). Improving child compliance on a computer-administered nonword repetition task. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(3), 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puolakanaho, A., Poikkeus, A. M., Ahonen, T., Tolvanen, A., & Lyytinen, H. (2003). Assessment of three-and-a-half-year-old children’s emerging phonological awareness in a computer animation context. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 36(5), 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puolakanaho, A., Poikkeus, A. M., Ahonen, T., Tolvanen, A., & Lyytinen, H. (2004). Emerging phonological awareness differentiates children with and without familial risk for dyslexia after controlling for general language skills. Annals of Dyslexia, 54, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roid, G. H. (2006). Designing ability tests. In S. M. Downing, & T. M. Haladyna (Eds.), Handbook of test development (pp. 527–542). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, R. W., Brock, K. L., Koul, R., Shane, H., & Flynn, S. (2019). Does animation facilitate understanding of graphic symbols representing verbs in children with autism spectrum disorder? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(4), 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, R. W., Choe, N., Koul, R., Shane, H. C., Yu, C., & Wu, M. (2022). Roles of animation in augmentative and alternative communication: A scoping review. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 9(4), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, R. W., Koul, R., Shane, H., Sorce, J., Brock, K., Harmon, A., Moerlein, D., & Hearn, E. (2014). Effects of animation on naming and identification across two graphic symbol sets representing verbs and prepositions. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(5), 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnotz, W., & Lowe, R. K. (2008). A unified view of learning from animated and static graphics. In R. K. Lowe, & W. Schnotz (Eds.), Learning with animation: Research implications for design (pp. 304–356). Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303206444_A_Unified_View_of_Learning_from_Animated_and_Static_Graphics (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- So, W. C., Wong, M. Y., Cabibihan, J. J., Lam, C. Y., Chan, R. Y., & Qian, H. H. (2016). Using robot animation to promote gestural skills in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32(6), 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommy, C. A., & Minoi, J. L. (2016, December 4–8). Speech therapy mobile application for speech and language impairment children. 2016 IEEE EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and sciences (IECBES) (pp. 199–203), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tversky, B., Morrison, J. B., & Betrancourt, M. (2002). Animation: Can it facilitate? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 57(4), 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, T. I., Kambanaros, M., Plotas, P., & Georgopoulos, V. C. (2024). Evidence of language development using brief animated stimuli: A systematic review. Brain Sciences, 14(2), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Children aged 0 to 18 years regardless of typical or atypical development, race, gender, language, or socioeconomic status |

| Concept | Use of animation for the development of an assessment game, task, or test for children |

| Context | Formal and informal assessments at any stage of the research process aimed at evaluating speech, language, communication, or related cognitive skills |

| Administration manner/Settings | Face-to-face or remote video platforms/Home, clinic, school, etc. |

| Study designs | Quantitative research. Experimental and quasi-experimental studies, developmental studies, and psychometrical and standardization studies |

| Limits | Papers in English language since 2000 without local restrictions. |

| Exclusion criteria | Studies exploring Theory of Mind (ToM), first and second language instruction, television animation viewing, eye-tracking, virtual reality, and avatars Studies that used animations without a clear assessment purpose Qualitative research, opinion reports, and gray literature |

| Database | Search | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=animation+AND+children+AND+%28assessment+OR+evaluation+OR+testing%29+AND+%28autism+OR+intellectual+disabilities+OR+language+disorders+OR+communication+disorders+OR+speech+disorders%29&filter=lang.english&filter=years.2000-2024 (accessed on 10 September 2024) | 86 (8 relevant) |

| Study | Name/Description | Study Design | Research Objectives | Participants | Areas of Assessment | Target Population | Purpose of Introducing Animation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gazella and Stockman (2003) | A story with animated puppets | Between-groups design | (a) To examine the possibility of standardizing a story-retelling task. (b) To determine whether the story presentation modality differentially influenced the children’s performance. | 29 TD children (4; 2 to 5; 6 years) | Language—grammatical and lexical skills | Language-delayed children | To provide a more realistic representation of the characters and actions, enhancing story comprehension. | The audio-only group did not differ significantly from the audiovisual group in narratives or responses to direct questions. |

| Puolakanaho et al. (2004) | Heps-Kups Land—Computer animation assessment program | Longitudinal developmental design | To provide a replication of previous group comparisons in a well-controlled and large sample of children with and without risk for dyslexia. | 98 children at risk for dyslexia and 91 TD children (3.5 years) | Language development—phonological awareness | Children with reading difficulties and/or dyslexia | To motivate children, revealing their phonological awareness skills. | (a) The control group manifested higher mastery than the at-risk group in phonological awareness. (b) Phonological awareness can be assessed long before reading instruction. (c) The tasks can be improved psychometrically. |

| Bishop et al. (2009) | Animation description task | Within-group design | To compare the sensitivity of different fTCD paradigms and to evaluate the novel task. | 21 TD children (4 years), 33 adults | Cerebral lateralization during spoken language generation | Young children with neurological conditions or non-clinical research samples | To engage the children. | The task appeared as valid and reliable as the other methods. |

| McGonigle-Chalmers et al. (2013) | The Eventaurs game | Single-case experimental design | To answer the following question: to what extent are nonverbal children with autism capable of overcoming the inherent executive demands of phrase construction via language-like production? | 9 low-functioning children with profound expressive language impairment and autism (5 to 17; 6 years | Syntactic awareness | Children with ASD | To depict an event as the result of a syntactically correct response in an engaging and motivating way that draws the attention of children. | (a) Νo child lacked syntactic awareness. (b) Εlementary syntactic control in a non-speech domain was superior to that manifested in their spoken language. |

| Alt (2013) | Two computer games with animated dinosaurs | Mixed (between-groups design and within-group design) | To examine whether children with SLI have impaired visual fast mapping skills and identify components of visual working memory contributing to the deficit. | 25 children with SLI and 25 TD children (7 and 8 years) | Visual fast mapping skills and visual working memory | Children with SLI | The visual features of the animated stimuli had to be identified by the children. | (a) There was evidence for impaired visual working memory skills for children with SLI, but not in all conditions. (b) There was no evidence that children with SLI were more susceptible to high-complexity information. (c) There was no evidence that children with SLI had limited capacity for visual memory. |

| Klop and Engelbrecht (2013) | Animated video story | Quantitative, comparative, between-subjects paradigm | To investigate whether a soundless animated video would elicit better narratives than a wordless picture book. | 20 TD children (8; 5 to 9; 4 years) | Narrative—story generation | Children with language impairments | To be compared with static pictures. | Both visual presentation modalities elicited narratives of similar quantity and quality. |

| Polišenská and Kapalková (2014) | Nonword Repetition Task | Cross-sectional developmental design | To develop a language assessment using consistent recorded nonword stimuli. To establish task validity and reliability. To examine the influence of environmental factors. | 391 TD children (2 to 6 years) | Language skills and phonological process | Children with language deficits | To increase compliance, participation, and engagement. | The task offers an objective delivery of recorded stimuli. It engages young children and provides high compliance rates. High levels of reliability. |

| Hodges et al. (2017) | The Monosyllable Imitation Test for Toddlers | Mixed (between-groups design and within-group design) | To investigate whether the stimulus characteristics have independent and/or convergent influences on imitation accuracy. To examine non-compliance rates and diagnostic accuracy. | 21 typically developing (TD) children and 21 children identified as late talkers (25 to 35 months) | Verbal imitation abilities, language development, and speech production | Toddlers with speech production difficulties | To provide reasons for imitation in an engaging and pragmatically motivating context. | (a) Stimuli characteristics influenced imitation accuracy. (b) Good compliance rates. (c) Reasonable diagnostic accuracy. |

| Badcock et al. (2018) | What Box task | Within-group design | To report a new method for eliciting language production for use with fTCD. | 95 TD children (1 to 5 years), 65 adults (60 to 85 years) | Language lateralization | Populations in which complex instructions are problematic (according to authors) | To engage children and to elicit covert or overt language. | The task was successfully employed in children using fTCD and showed medium correspondence with the Word Generation task. |

| Frizelle et al. (2018a) | Animated sentence-verification task | Within-group design | To examine the effect of two assessment methods. | 103 TD children (3; 6 to 4; 11 years) | Language development and comprehension of complex syntax | Children with receptive syntax deficits | To present the items in a pragmatically appropriate context that reflects how language is processed in natural discourse, allowing real-time processing. To reduce the memory demands and the interpretation of adult-created pictures. | (a) Better performance on the animated sentence-verification task. (b) Each testing method revealed a different hierarchy of constructions. (c) The impact of testing method was greater for some syntactic constructions than others. |

| Frizelle et al. (2018b) | Test of Complex Syntax–Electronic | Between-groups design | To assess how children with DS understand complex syntax. | 33 children with DS, 32 children with cognitive impairment, 33 TD children (the groups were matched on non-verbal mental age) | Language—understanding of complex syntax | Children with DS | To minimize non-linguistic demands. | (a) Children with DS performed “more poorly” on most of the sentences than both control groups. (b) DS status accounted for a significant proportion of the variance over and above memory skills. (c) TECS-E needs to be normed and standardized. |

| Diehm et al. (2020) | Animated stories | Within-group design | To investigate the effect of story presentation format (static picture book vs. animated video). | 73 TD children (3 to 5 years) | Language development—narrative retells | Children with language disorders | To prompt narrative elicitation. | Children performed significantly better when retelling the animated stories. |

| Petit et al. (2020b) | Congruent and incongruent animations | Within-group design | To assess the reliability of neural signals in response to semantic violations. | 20 neurotypical children (9 to 12 years) | Language comprehension/Lexical–semantic processing | Minimally verbal children with autism | To increase children’s engagement and to build up strong semantic contexts. | Children exhibited heterogenous neural responses. |

| De Villiers et al. (2021) | Quick Interactive Language Screener: English–Spanish | Between-groups design | To discuss theoretical and methodological problems in test development. To offer a process for developing, validating, and norming. | 362 TD children, dual-language learners (3 to 5; 11 years) | Language comprehension and language process in both languages | Bilingual children who are at risk for language difficulties | To provide a more precise depiction of event sequences and actions that may be challenging for young children to glean from still pictures. | The screener is a viable option for fair testing of bilingual Spanish–English children. |

| Krok et al. (2022) | Sentence Diversity Priming Task | Within-group design | To provide the rationale for assessing sentence diversity, describe the task, and present preliminary analyses of compliance and developmental associations. | 32 TD toddlers (30 to 35 months) | Sentence diversity | Children at risk for DLD | To simulate a familiar and enjoyable parent–child interaction context. To depict familiar actions to toddlers. | The task holds toddlers’ attention, reveals robust individual differences in their ability to produce sentences, is positively correlated with parent-reported language measures, and has the potential for assessing children’s language growth over time. |

| Pace et al. (2022) | Quick Interactive Language Screener | Between-groups design | To examine the classification accuracy. | Study 1: 67 children—54 with DLD and 13 TD (3; 0 to 6; 9 years); Study 2: 126 children—25 with DLD and 101 TD (3; 1 to 5; 11 years) | Language comprehension and language process | Children with DLD | To present various syntactic structures. | Findings support the clinical application of the QUILS for identifying DLD. |

| Jackson et al. (2023) | Quick Interactive Language Screener: Toddlers | Between-groups design | To develop a behavioral measure of children’s language capabilities at age two. | Phase I (Pilot): 174 children (22; 7 to 39; 1 months); Phase II: 252 children (2; 0 to 2; 11 years); Phase III: 448 children (2; 0 to 2; 11 years) | Language comprehension and language process | Children at risk for language impairment | To portray verbs and events requiring children to make fewer inferences from static pictures. | The screener could support research studies and facilitate the early detection of language problems. |

| Lloyd-Esenkaya et al. (2024) | Zoti’s Social Toolkit | Within-group design | To develop a measure which assesses emotional understanding and conflict resolution with minimal reliance on language skills. To investigate the face and construct validity of the measure. | Study 1: 91 TD children (9 to 11 years); Study 2: 5 TD children (7 to 8 years); Study 3: 20 TD adults (18 to 25 years); Study 4: 20 TD and 22 DLD children (7 to 9 years) | Emotion inferencing and conflict resolution knowledge | Children with DLD | To ensure participants can fulfill the requirements of the task even if they have a language disorder. | The final toolkit is suitable for children with and without a language disorder. |

| Study | Name/Description | Original or Commercially Available | Technical Description | Speed of Frames | Duration | Examples of Animation | Auditory Input | Theoretical or Research Basis for the Use of Animation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gazella and Stockman (2003) | A story with animated puppets | Original | Video-based animation with puppets | No report; smooth transitions between scenes | No report | No | Yes | The authors relied on the relevant literature on video-based story presentations |

| Puolakanaho et al. (2004) | Heps-Kups Land—Computer animation assessment program | Original | Like spontaneous speech game | No report | No report | No | Yes | The task types presented in the literature were modified and embedded within a computer animation context |

| Bishop et al. (2009) | Animation description task | Original | Animated cartoon clips | No report | 30 clips per 12 s | No (available on request) | Yes (sounds, no speech) | Previous pilot studies were reported |

| McGonigle-Chalmers et al. (2013) | The Eventaurs game | Original | 3D-colored animations using Macromedia Flash 5.3 | No report | No report | Yes (figures) | Yes | The game is based on a previous study (McGonigle & Chalmers, 2002) |

| Alt (2013) | Two computer games with animated dinosaurs | Original | Short animated scenes using Adobe Flash software. | No report | 10 vignettes per 10 s | Yes (figures) | No | No report |

| Klop and Engelbrecht (2013) | Animated video story | Original | A simulation of the compared color picture book; animation effects depicted character movements, facial speech movements, and fading between pictures; no distracting backgrounds | No report | Total time 2 min; one picture at a time | Yes (pictures) | No | The authors relied on the literature comparing animated versus static picture presentations |

| Polišenská and Kapalková (2014) | Nonword Repetition Task | Original | A color necklace simulation where the beads were introduced through PowerPoint software animated effects; the task was embedded in a short story | No report | 1.33 min | Yes (video) | Yes | No report |

| Hodges et al. (2017) | The Monosyllable Imitation Test for Toddlers | Original | Two computer-animated stories were created using the iPad applications PhotoPuppet HD and iMovie | No report | 2.24 min per episode | No | Yes | No report |

| Badcock et al. (2018) | What Box task | Original | Animation of a face “searching” for an object; created with a series of still-frame images | A detailed schematic diagram of the task time periods and animation frames is provided | Total task time 34 s | Yes (figure) | Yes | The task was based on previous literature on fTCD methods |

| Frizelle et al. (2018a) | Animated sentence-verification task | Original | No report | No report | 6 s average | Yes (video) | Yes | The authors relied on previous literature on truth-value-judgment/sentence-verification assessments |

| Frizelle et al. (2018b) | Test of Complex Syntax–Electronic | Original | No report | No report | 6 s average | Yes (video) | Yes | The study was based on Frizelle et al. (2018a) |

| Diehm et al. (2020) | Animated stories | Available online | Video-based animation | No report | 2.15 to 2.35 min | No | Yes | The authors relied on previous literature regarding multimedia features |

| Petit et al. (2020b) | Congruent and incongruent animations | Original | Short, colorful animated cartoons developed using Adobe Photoshop CC 2017 | Yes | 3 s minimum | Yes (figures and videos) | Yes | The task was based on the prior study of Petit et al. (2020a) |

| De Villiers et al. (2021) | Quick Interactive Language Screener: English–Spanish | Original | No report | No report | No report | Yes (figures) | Yes | No report |

| Krok et al. (2022) | Sentence Diversity Priming Task | Original | Simulation of a colorful animated picture book with minimal background distractions; developed with online animation tools and presented in Microsoft PowerPoint | No report | 10 s | Yes (figures) | No | The task was based on the prior study of Krok and Leonard (2018) |

| Pace et al. (2022) | Quick Interactive Language Screener | Original | No report | No report | No report | Yes (figures) | Yes | No report |

| Jackson et al. (2023) | Quick Interactive Language Screener: Toddlers | Original | A game on a touchscreen | No report | No report | Yes (figures) | Yes | The authors relied on literature concerning animation use, developmental milestones, and modes of introduction |

| Lloyd-Esenkaya et al. (2024) | Zoti’s Social Toolkit | Original | Colored animated scenarios with characters lacking facial features or expressions; stop-motion technique: for every animation, several digitally drawn image frames are joined together using animation software | No report | ~11 s | Yes (figures and videos) | Yes | The authors relied on the study of Ford and Milosky (2008) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vlachou, T.I.; Kambanaros, M.; Terzi, A.; Georgopoulos, V.C. Animation in Speech, Language, and Communication Assessment of Children: A Scoping Review. Languages 2026, 11, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages11020024

Vlachou TI, Kambanaros M, Terzi A, Georgopoulos VC. Animation in Speech, Language, and Communication Assessment of Children: A Scoping Review. Languages. 2026; 11(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages11020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleVlachou, Triantafyllia I., Maria Kambanaros, Arhonto Terzi, and Voula C. Georgopoulos. 2026. "Animation in Speech, Language, and Communication Assessment of Children: A Scoping Review" Languages 11, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages11020024

APA StyleVlachou, T. I., Kambanaros, M., Terzi, A., & Georgopoulos, V. C. (2026). Animation in Speech, Language, and Communication Assessment of Children: A Scoping Review. Languages, 11(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages11020024