Abstract

This paper introduces an estimation procedure for a random effects probit model in presence of heteroskedasticity and a likelihood ratio test for homoskedasticity. The cases where the heteroskedasticity is due to individual effects or idiosyncratic errors or both are analyzed. Monte Carlo simulations show that the test performs well in the case of high degree of heteroskedasticity. Furthermore, the power of the test increases with larger individual and time dimensions. The robustness analysis shows that applying the wrong approach may generate misleading results except for the case where both individual effects and idiosyncratic errors are modelled as heteroskedastic.

JEL Classification:

C23; C61; C63

1. Introduction

The problem that heteroskedasticity presents for panel data regression has been widely discussed in the literature (Baltagi 2008; Baltagi et al. 2006; Montes-Rojas and Sosa-Escudero 2011). Let us consider the one-way error component model, i.e., with the error term defined as where the individual effects and the idiosyncratic errors are assumed to be random (i.e., and ). Several authors (Baltagi 1988; Mazodier and Trognon 1978; Randolph 1988; Wansbeek 1989, among others) consider different types of heteroskedasticity depending upon whether individual effects () or idiosyncratic errors () or both are heteroskedastic. Baltagi et al. (2006) and later Montes-Rojas and Sosa-Escudero (2011) proposed Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test procedures to check for the presence of heteroskedasticity in linear models for various cases. However, such test procedures for panel data binary choice models are lacking. In addition, to the best of my knowledge, there is no existing procedure to estimate an heteroskedastic probit model on panel data.

The use of random effects probit models panel data has been popularized due to the problem of incidental parameters (Baltagi 2008; Lancaster 2000). Since this model is generally applied to micro-panels, heteroskedasticity problems are likely to arise. One must account for heteroskedasticity since it could result in misleading conclusions about coefficients and marginal effects interpretation (Greene 2012). Two approaches are used to calculate the marginal effects after probit models in applied works: (i) integrating with respect to individual effects, or (ii) assuming the individual effects to be null (Bland and Cook 2018). In the case (i), the probability of positive outcome is given by while in case (ii), this probability is given by , where and are respectively the standard normal cumulative probability and the standard normal density functions. Thus, the marginal effect for variable (denoted ) is given by Equation (1) for case (i) and Equation (2) for case (ii):

In Equations (1) and (2), it clearly appears that the marginal effects estimated in both case (i) and (ii) depend on the variance components. Since these variance components are functions of individual characteristics in the presence of heteroskedasticity, thus considering an homoskedastic model yields misestimated marginal effects. This stresses the need for an empirical implementation of an estimation and test procedure to deal with heteroskedasticity on panel probit models.

The aim of this paper is to introduce an estimation procedure that accounts for this heteroskedasticity using the Gauss-Hermite quadrature scheme1. In addition, the papers aims at providing a likelihood ratio (LR) test procedure for homoskedasticity in a panel probit model that allows one to investigate various forms of heteroskedasticity under alternative hypothesis. Monte Carlo simulations are conducted to estimate the power and the empirical size of the test and a robustness analysis is completed to ensure that the test and estimation procedures perform well. Results suggest that the estimation procedure has good performances and that it performance also depends on the quadrature parameters. The LR test has excellent power when there is high degree of heteroskedasticity and its performance depends on sample size in the situation of low degree of heteroskedasticity. The contribution of this paper to the literature is twofold. Firstly, it introduces a procedure to estimate a panel probit model with heteroskedasticity. The procedure allows one to deal with different sources of heteroskedasticity. Secondly, based on the power and the empirical size of the test, it shows that the LR test for homoskedasticity has good performance. The robustness of the estimation procedure and the test performance have been assessed using an extensive Monte Carlo simulation.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the different forms of heteroskedasticity encountered in the literature and derives the likelihood estimator in a general setting. Section 3 discusses the estimation requirements and test procedures to deal with heteroskedasticity. In Section 4, the power and the empirical size of the test as well as the bias and the mean square error of the estimated parameters are computed based on Monte Carlo simulations. Section 5 presents robustness analysis. Section 6 presents a case study that illustrates the estimation of the parameters and marginal effects in the presence of heteroskedasticity. Section 7 concludes.

2. Heteroskedasticity and Likelihood Function

This section discusses the different types of heteroskedasticity encountered in the literature and specifies the likelihood function.

2.1. Different Sources of Heteroskedasticity

Consider the following one-way error components probit model:

where is decomposed in individual unobserved effects () and idiosyncratic errors (). We consider the random effects model. Classical assumptions for the estimation of a random effects model are the following: (i) the individual effects are independent from the idiosyncratic errors , and (ii) the explanatory variables are independent from the individual effects and the idiosyncratic errors . In addition, some assumptions are made on the variance components to deal with heteroskedasticity issues. These assumptions lead to three cases of heteroskedasticity identified in the literature:

- Heteroskedasticity a la Mazodier and Trognon (1978): The heteroskedasticity is due to the individual effects. Thus, and .

- Heteroskedasticity a la Baltagi (1988) and Wansbeek (1989): the heteroskedasticity is due to the idiosyncratic errors. Thus, and .

- Heteroskedasticity a la Randolph (1988): The heteroskedasticity is due to both the individual effects and the idiosyncratic errors. Thus, and . An alternative specification by Verbon (1980) is to consider that and .

In this paper, the heteroskedastic component is assumed to a function of some observed variables. More specifically, when the heteroskedasticity is due to the , the variance depends on time-invariant exogenous variables and expressed as . Alternatively, when the heteroskedasticity is due to the , the variance depends on exogenous variables and has the following expression: . The approach of Verbon (1980) can be modelled with a variance of idiosyncratic errors that is . The functions and are twice continuously differentiable and satisfy , , and . and are vectors of regressors and have no constant term included. Note that the variance of the idiosyncratic errors is set to one () in order to avoid identification problems (Greene 2012). This identification problem occurs when a constant term is included since it implies that the variance of idiosyncratic errors will not be 1 when is null.

In the rest of the paper, as in Montes-Rojas and Sosa-Escudero (2011) and Baltagi et al. (2006), the results are reported for the functions and set to exponential functions. Then, and . Thus, the variance of the individual effects can be rewritten as , with .

2.2. Likelihood Function

The individual level likelihood is given by:

where denotes the standard normal cumulative distribution function, denotes the density function of a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance equal to the variance of that is , and

Note that this general form of the likelihood function allows dealing with homoskedasticity and each of the aforementioned heteroskedasticity cases. The homoskedastic model is given by . The heteroskedastic model where are heteroskedastic is given by and ; the heteroskedastic model where are heteroskedastic is given by and ; while the heteroskedastic model where both and are heteroskedastic is given by and .

3. Estimation and Tests

The estimation procedure was based on a Gauss–Hermite quadrature scheme. This section discusses the requirements for the use of this approach. Then, the procedure to test for homoskedasticity is presented.

3.1. Estimation Requirements

Given that the likelihood function (Equation (4)) has an integral form, it is common in the literature to use a numerical integration method. Gauss–Hermite quadrature is used to provide an approximation of the likelihood function that has a tractable form for likelihood maximization algorithms (Liu and Pierce 1994; Naylor and Smith 1982). It consists in approximating the integral by a weighted sum of the function taken at some specific points called nodes.

The Gauss–Hermite quadrature scheme used herein is the one proposed by Liu and Pierce (1994). Let Q denotes the number of quadrature points, and denote respectively the quadrature points (nodes) and their corresponding weights. Then, the individual level likelihood is given in Equation (4) can be re-expressed as a sum of functions as follows:

With

where denotes the density function of the standard normal distribution2.

The individual level log-likelihood function depends on the selected number of quadrature points Q. A discussion based on empirical applications of the effect of the number of quadrature points on the estimation results and the computing time is presented by Moussa and Delattre (2018). Researchers can check the impact of a selected number of quadrature points on the results. A quadrature points check is conducted in Section 5 for the model with heteroskedasticity due to both and that is the most complete case of heteroskedasticity in panel models3.

3.2. Test Procedure

As described by Greene (2012), the issue of heteroskedasticity test can be analyzed using a misspecification test procedure. The homoskedastic panel probit model can be viewed as a restricted model in which and are constrained to be null ( and are omitted in the model). Thus, the homoskedastic probit model is nested in the heteroskedastic one. The omitted variables tests in literature are based on the likelihood-ratio (LR), the Lagrange multiplier (LM), and the Wald test. These three tests are asymptotically equivalent. However, this equivalence is valid for probit models only if the error components are homoskedastic and uncorrelated over time (Lechner 1995). The following relationship between test statistics for linear models has been proved (, Johnston and DiNardo 2001). This implies that the LM test is less likely to reject the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity. In the literature, the LM test is mostly used to test for homoskedasticity in linear models even for panel data models (Baltagi et al. 2006; Montes-Rojas and Sosa-Escudero 2011). The LR test is mainly used for nonlinear models. On the cross-section probit model, Davidson and MacKinnon (1984) show that the LR test performs well. The Wald test has poor performance on finite sample when testing for nonlinear hypothesis (Davidson and MacKinnon 1984; Wooldridge 2001). The power of the LM test for homoskedasticity on probit model may be problematic since it fails to distinguish between heteroskedasticity and simple omission of a variable in the index function (Greene 2018; Davidson and MacKinnon 1984).

For the aforementioned reasons, the heteroskedasticity tests used herein are based on the LR test procedure. LR test addresses the issue of the change in model fit when new variables are added (Wooldridge 2001). Thus, it requires the estimation of both the full heteroskedastic and the homoskedastic models. Since the aim of this paper is to propose an estimation procedure of a random effects probit model for panel data in presence of heteroskedasticity, the LR statistics will be easy to compute. The LR test statistics is given by:

where and denote the log-likelihood of the restricted and unrestricted models respectively, and p is the number of parameters that are omitted in the homoskedastic panel probit model, i.e., the dimension (number of column) of or or the sum of the dimensions of and .

Following the sources of the heteroskedasticity and as specified by Baltagi et al. (2006), three types of hypothesis can be tested. These hypothesis are related to the joint test for homoskedasticity of both individual effects and idiosyncratic errors () and to the two marginal tests for homoskedasticity of one of the aforementioned error components assuming the other component homoskedastic (i.e., and ).

Monte Carlo simulations are conducted in Section 4 to check for the robustness of the test by estimating its power and empirical size. The power of the test is defined as the percentage of rejection at 5% significance level of the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity in presence of heteroskedasticity. The empirical size refers to the percentage of false rejection at 5% significance level of the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity.

4. Monte Carlo Experiments

The Monte Carlo4 experiments conducted herein are based on a data generated as follows. For and the binary dependant variable is generated as:

where and are generated from a random uniform distribution. The error components and are generated following a normal data generating process with zero mean and standard deviation and respectively. The time invariant variable and the variable are generated from a random uniform distribution. The parameters of the index function are set to , , and . For each type of heteroskedasticity presented in Section 2, nine (9) Monte Carlo experiments in which and are conducted with 5000 replications.

To estimate the power of the test, two cases are considered. The first set of experiments consists of a generated dataset with low degree of heteroskedasticity (i.e., setting and ). A second set of experiments consists of a generated dataset with a high degree of heteroskedasticity (i.e., setting and ) for each of the 27 models aforementioned. In these experiments, the variance of the individual effects is set to (i.e., ). The results of these experiments are presented in Section 4.1. The empirical size of the test is estimated using a generated dataset with no heteroskedasticity (i.e., setting ). A well performing test would be such that its empirical size does not significantly differ from the nominal size of 5%. The results of these simulations are presented in Section 4.1.

Further Monte Carlo experiments have been conducted to cover several situations. These experiments consist of setting the following parameters: , and . The results of this second set of experiments for and are reported in Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3 in Appendix D.

4.1. Power and Empirical Size of the Test

Table 1 shows the power of the LR test for each of the aforementioned experiments. The Monte Carlo experiment for the marginal test reveals that the test performs well in the case of high degree of heteroskedasticity even for small samples ( and , the power of the LR test is 81.72%). However, in the case of low degree of heteroskedasticity, the test does not perform well on a sample with small N. For , the power of the test is 12.04% when and increasing T to 10 and 20 yields in a power of 19.9% and 27.4% respectively. But, the power of the LR test is very high for a sample with large N. For , the power of the test is respectively 69.54% for , 94.14% for and 99.26% for . Nonetheless, increasing from 0.2 a larger value, say 2 or 6 results in a decrease in the power of the test when T is large and to an increase of the power of the test when T is low (see Table A2 in Appendix D).

Table 1.

Power of the likelihood ratio (LR) test for homoskedasticity based on 5000 replications.

For the marginal test , the Monte Carlo experiment shows that the performance of the test is mitigated for small samples in presence of high heteroskedasticity. With , when the power of the test is 47.78%. However, increasing the time dimension to and the power of the test increases drastically to 93.7% and 99.98% respectively. In the case of low degree of heteroskedasticity, the power of the test is very high when N or T is large. When N is small, the performance is low (22.86% with and ) and increases with T (39.74% with and 67.14% with ). Nonetheless, increasing from 0.2 a larger value, say two or six results in a drastic increase in the power of the test (see Table A3 in Appendix D).

As for the joint test , the Monte Carlo experiment reveals that the test has good performance in the case of high heteroskedasticity even when N is small. For , the power of the test is 65.16% with and reaches 100% with . In the case of low degree of heteroskedasticity, the power of the test is excellent when N or T is large. For small N, the power of the test is low. It is 14.62% when and , and when T is fixed at 5, increasing N to 500 yields in a drastic increase in the power of the test (96.74%). Nonetheless, fixing N at 50 and increasing T to 10 and 20 yields in a power of the test of 35.16% and 63.74% respectively. Furthermore, increasing from 0.2 a larger value, say two or six results in an increase in the power of the test (see Table A1 in Appendix D).

Table 2 presents the empirical size of the test based the Monte Carlo experiments described above. The empirical size of the test varies between 4.54% and 5.36%. The empirical size of the test varies between 4.48% and 5.54% and between 4.52% and 5.14% in the case of the joint test . All these empirical sizes do not significantly differ from the nominal size5 of the test.

Table 2.

Empirical size of the LR test for homoskedasticity based on 5000 replications.

4.2. Bias and Mean Square Error of the Estimates

This subsection aims at evaluating the robustness of the proposed estimation procedure. For this purpose, the modelling approach for the case where both and are heteroskedastic is used. The parameters of the model are those set in Section 4. The bias and the mean square error (MSE) of the estimates are computed based on 5000 replications for and . The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Bias and mean square error (MSE) of the estimates based on 5000 replications.

The results suggest that the MSEs of both index function and variance parameters decrease with the number of observations. The bias of the index function parameters are lower than 5% regardless of the individual and time dimensions of the panel. The bias for the parameters of the variance of and becomes lower as the time dimension of the panel increases. It reaches 5% for .

4.3. Robustness of Validity

In this subsection, the robustness of validity of the test procedure is assessed using the framework described by Montes-Rojas and Sosa-Escudero (2011). The aim is to assess how the departure away from normality of the data generating process (DGP) of the error components might affect the results of the test. For this purpose, the empirical size of the tests (, , and ) is computed for and using 5000 replications. The empirical sizes for normal, student with three degrees of freedom, exponential, uniform, and chi-square DGP are estimated respectively. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Empirical size of the test based on 5000 replications for and .

The results suggest that a deviation from the normal DGP has heavy consequences on the empirical size on the test. The higher effect on the empirical size of the test is observed for exponential DGP. These results were expected since the estimation procedure, i.e., the Gauss–Hermite quadrature, is accurate only when the integral function has a Gaussian factor.

5. Additional Robustness Checks

To further check for the robustness of the proposed approach, three analysis are conducted. Based on data simulated with parameters setted in Section 4, the first analysis consists in checking whether the estimation procedure provides estimates that are consistent with the data generating process. This analysis complements the measure of bias and MSE done in Section 4.2 by focusing of the difference between each estimated parameter and the DGP. The second robustness analysis consists in checking the effect of the number of quadrature points on the estimated parameters. The third analysis focuses on the robustness to misspecified heteroskedasticity, i.e., how the test procedure performs when a researcher applies the wrong test.

5.1. Application Examples and Comparisons

For each of the three cases of heteroskedasticity described in Section 2, two applications are provided: (i) the first on a random sample of size and , (ii) and the second on a random sample of size and . For each of these applications, comparisons with the homoskedastic panel probit and the heteroskedastic pooled probit models are provided. The log-likelihood and the LR statistics are provided for the heteroskedastic pooled probit and the heteroskedastic panel probit models. Estimates are in the Appendix E for models with heteroskedasticity due to are provided in Table A4, those of models with heteroskedasticity due to are provided in Table A5, and Table A6 provides the estimates of models with heteroskedasticity due to both and .

Results suggest that in the presence of heteroskedasticity due to , the pooled heteroskedastic model underestimates the heteroskedastic factor (coefficient of variable ) for both and models. The homoskedastic part of the variance is well estimated using the homoskedastic panel probit model. It also appears that the parameters estimated from the homoskedastic and the heteroskedastic panel probit models are not different. However, as expected, the pooled model yields to bias in the estimated parameters especially when T is large.

In the presence of heteroskedasticity due to , the pooled heteroskedastic model gives correct estimates of the heteroskedastic factor (coefficient of variable ) and the parameters of the model with . However, with , the estimated parameters are different from that of the data generating process (DGP). These estimates are not different from those provided by the pooled heteroskedastic model. The homoskedastic panel probit model yields estimates of parameters and variance components that differ from the DGP.

The estimation of the model with heteroskedasticity due to both and by a homoskedastic panel probit model leads to parameters that are different from the DGP. The heteroskedatic pooled probit model yields to estimated individual effects variance that is different from the DGP.

5.2. Quadrature Points Check

The data generated for the examples in Section 5.1 with and are used for the quadrature points check. This quadrature check is conducted on the heteroskedastic model where the heteroskedasticity is due to both and which is the more general case of heteroskedasticity.

The quadrature points check shows that using Q under 10, in this example, leads to significant differences in the estimated parameters from the DGP (See details in Table A7 in the Appendix F). For or more quadrature points, the estimated parameters are not significantly different from the DGP. Furthermore, as the number of quadrature points increases, the estimated parameters converge to the DGP’s values and become more accurate. This result has also been found in several applications that use Gauss–Hermite quadrature (Baltagi 2008; Moussa and Delattre 2018). Moreover, for , the relative difference in log-likelihood is around while the relative difference in the LR statistics is around . In terms of computation time, the convergence is generally reached quickly. It takes from 41 seconds for to 133 seconds for for the model to converge. However, the computation time may vary considerably according to the number of explanatory variables and to the sample size.

5.3. Misspecified Heteroskedasticity: Effects of Applying the Wrong Approach

To check for robustness, this subsection analyzes what happens when researchers apply the wrong heteroskedasticity modelling approach to a model with heteroskedasticity. For example, what happens if in the presence of heteroskedasticity due to both and , researchers apply the procedure for estimation of heteroskedasticity due to ? A second set of robustness check consists in applying one of the three tests to a homoskedastic model. For this purpose, the data generated in Section 5.1 for the examples with and are used. Thus, for each case, the number of quadrature points is set to . For example, on a dataset generated with heteroskedastic, the heteroskedasticity due to and the heteroskedasticity due to both and modelling approaches are applied.

Table 5 shows the results of LR tests and the variance components for each of the aforementioned cases. Results suggest that when only are heteroskedastic, the application of the heteroskedasticity due to modelling approach results in incorrect estimates for the variance components and the LR test concludes to the presence of heteroskedasticity due to . The results of Monte Carlo simulations presented in Table A3 in Appendix D show that the acceptance rate of the null hypothesis in such a situation varies between 6.6% and 96.4% according to the panel’s dimension and the degree of heteroskedasticity. Furthermore, the higher the variance of , the higher the acceptance rate. Contrary to the latter and as expected, if researchers apply the heteroskedasticity due to both and modelling approach, the results are consistent with that obtained when applying the right approach and the parameter that indicates the presence of heteroskedasticity due to is not significantly different from zero. The same results hold for the case where only are heteroskedastic except that the LR test concludes to no presence of heteroskedasticity due to when this modelling approach is used. The results from Monte Carlo simulations presented in Table A1 in Appendix D show that the acceptance rate of the null hypothesis does not significantly differ from 5%. In the case where both and are heteroskedastic, applying the wrong modelling approach yields in identification of the related heteroskedasticity while the others forms are ignored. For example, if researchers apply the heteroskedasticity due to modelling approach, the LR test concludes to the existence of heteroskedasticity due to while the heteroskedasticity from the individual effects is ignored. The Monte Carlo simulations conducted (see Table A2 and Table A3 in Appendix D) show that the power of the test is close to that of the right test. This result suggest that it is better starting by the heteroskedasticity due to both and modelling approach. Then, if one of the sources has no significant contribution to heteroskedasticity, then researchers can turn to the other source with the use of the specific modelling approach.

Table 5.

Estimated variance components and LR tests on wrong models.

Table 6 shows the results of the application of one of the three tests to a situation where there is no heteroskedasticity. As expected, the LR tests conclude to homoskedasticity for all of the three modelling approaches. The Monte Carlo simulations conducted show that the acceptance rate of the null hypothesis does not differ significantly from the nominal size of the test (see Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3 in Appendix D).

Table 6.

Estimated variance components and LR tests on homoskedastic model.

6. Case Study

In this section, the illustration dataset for panel probit models used by Greene (2012) and refereed as Example 17.11 pp. 274–275 is used. This dataset is related to German health care utilization and contains 26,326 observations with and T varying between 1 and 7. The model estimates the effects of socioeconomic variables (age, income, kids, education, and marital status) on the probability to visit a doctor. The results by Greene (2012) are replicated and the marginal effects are calculated with respect to the two approaches aforementioned. Then, the heteroskedastic probit model in the more general setting where both and are heteroskedastic is estimated and the marginal effects are computed. Table 7 shows the results of the estimates for the two approaches.

Table 7.

Estimated coefficients and marginal effects.

The LR test of homoskedasticity leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity. Thus, there is the presence of heteroskedasticity due to both and . The estimated parameters are significantly different between the homoskedastic and the heteroskedastic models. The same result holds for the marginal effects. However, the differences in marginal effects are lower using the marginal effects integrated with respect to that the ones computed assuming . Using the former approach, results suggest that ageing increases by 0.55% the probability to visit a doctor using the homoskedastic model and by 0.61% using the heteroskedastic model. These estimates are respectively 0.69% and 0.76% using the second approach. An increase in the number education years reduces by 0.92% the probability of visiting a doctor using the homoskedastic model and by 0.38% using the heteroskedastic model. Assuming , an increase in the number of education years reduce by 1.16% the probability of visiting a doctor using the homoskedastic model while the effect is not significant using the heteroskedastic model.

7. Conclusions

The use of a random effects probit model has been popularized due to the problem of incidental parameters encountered when dealing with fixed effects models for binary outcomes in panel data. However, researchers do not test for the presence of heteroskedasticity in the error terms and then do not control for that when estimating these models. This paper proposes an estimation procedure that accounts for heteroskedasticity for both individual effects and idiosyncratic errors separately and jointly as well as a LR test for homoskedasticity.

A Monte Carlo experiment was conducted to estimate the power of the test. It shows that the LR test performs well generally. However, on samples with a low degree of heteroskedasticity, the power of the test is around 20% for panels with small N and T but it increases drastically with larger N and T. The analysis also show that applying the wrong estimation and test procedures may yield misleading conclusions about heteroskedasticity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Désiré Kanga and Vakaramoko Diaby for their helpful comments on earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

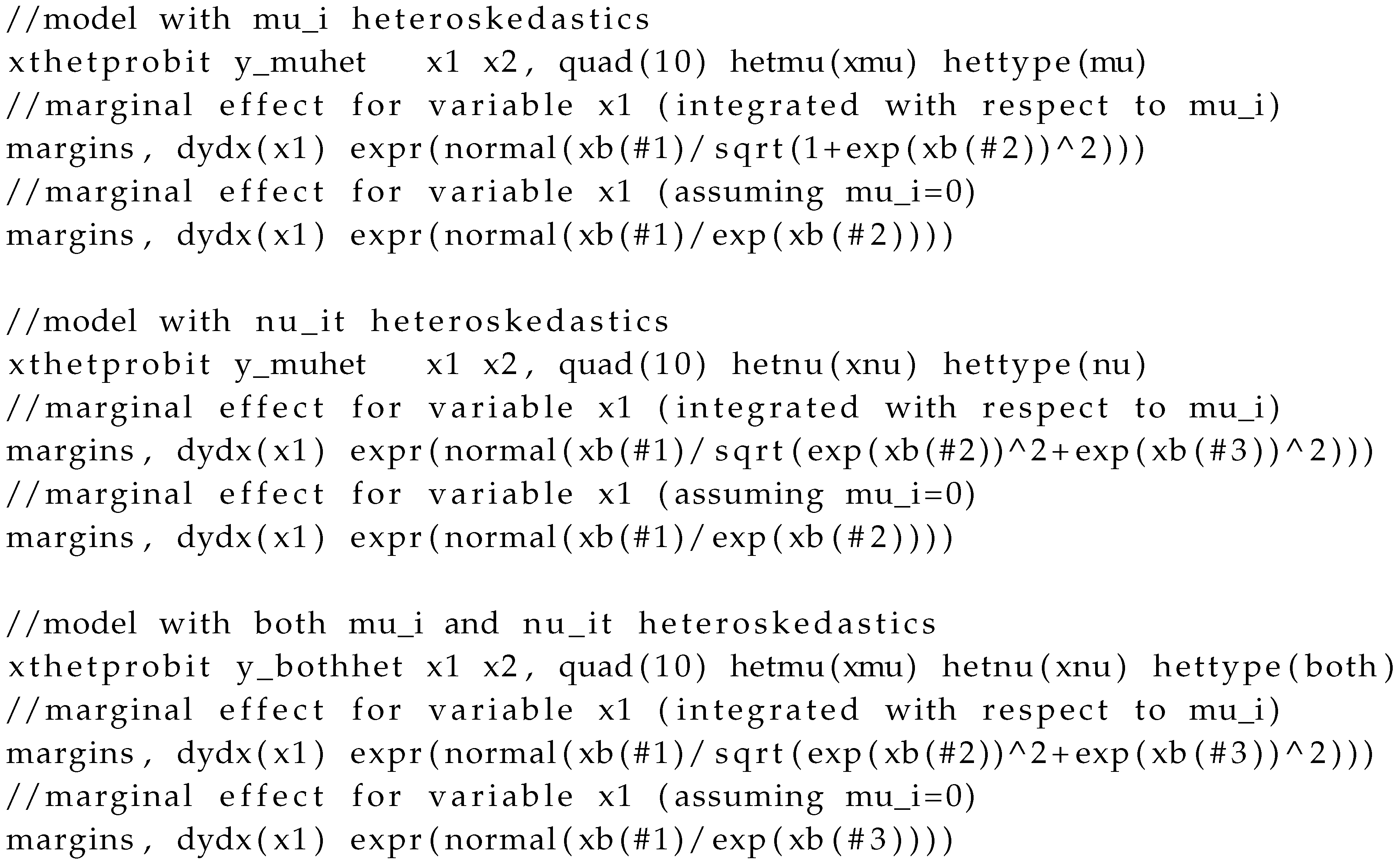

Appendix A. STATA Code for Computing the Marginal Effects

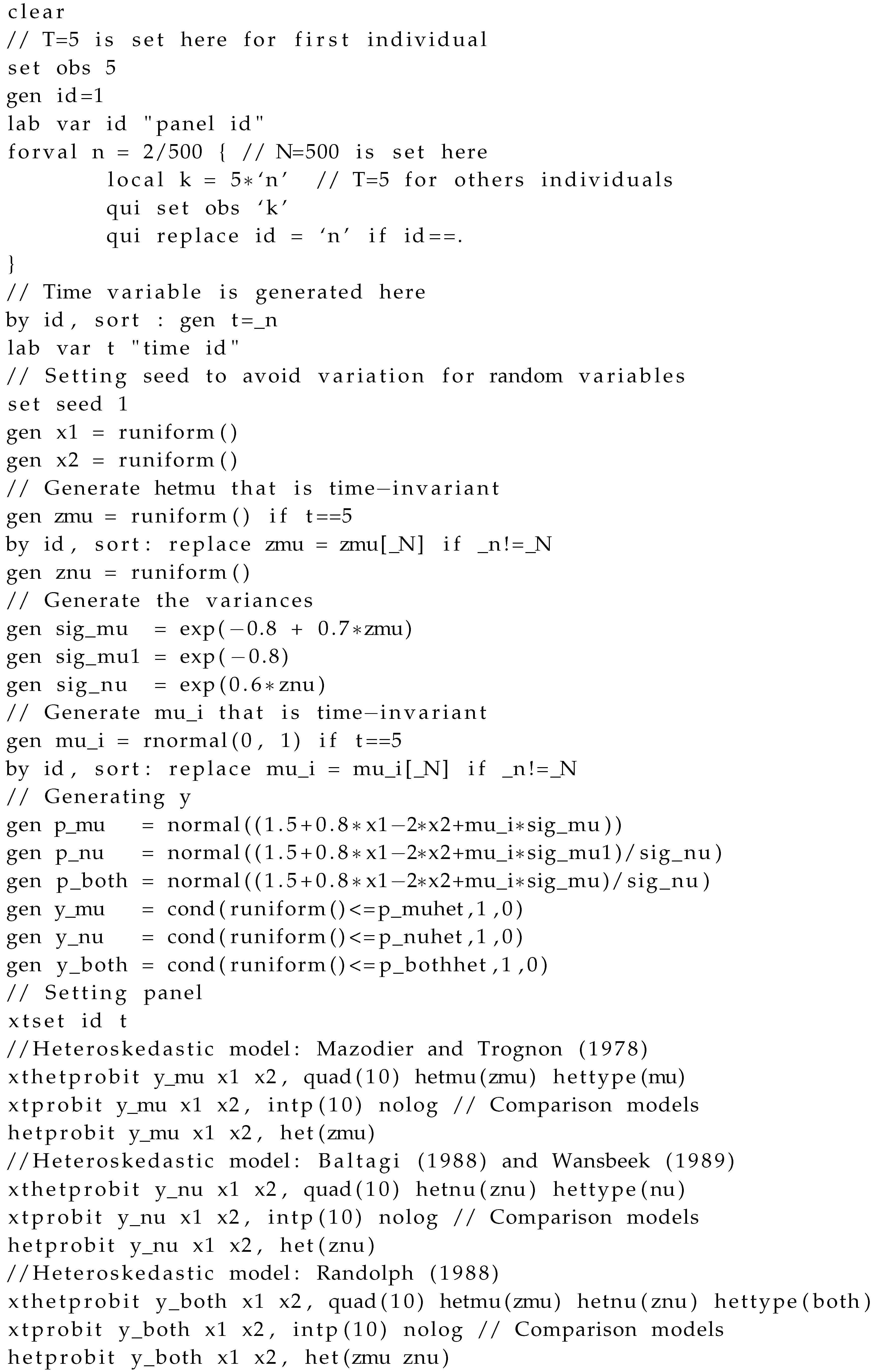

Appendix B. STATA Code for Generating the Dataset

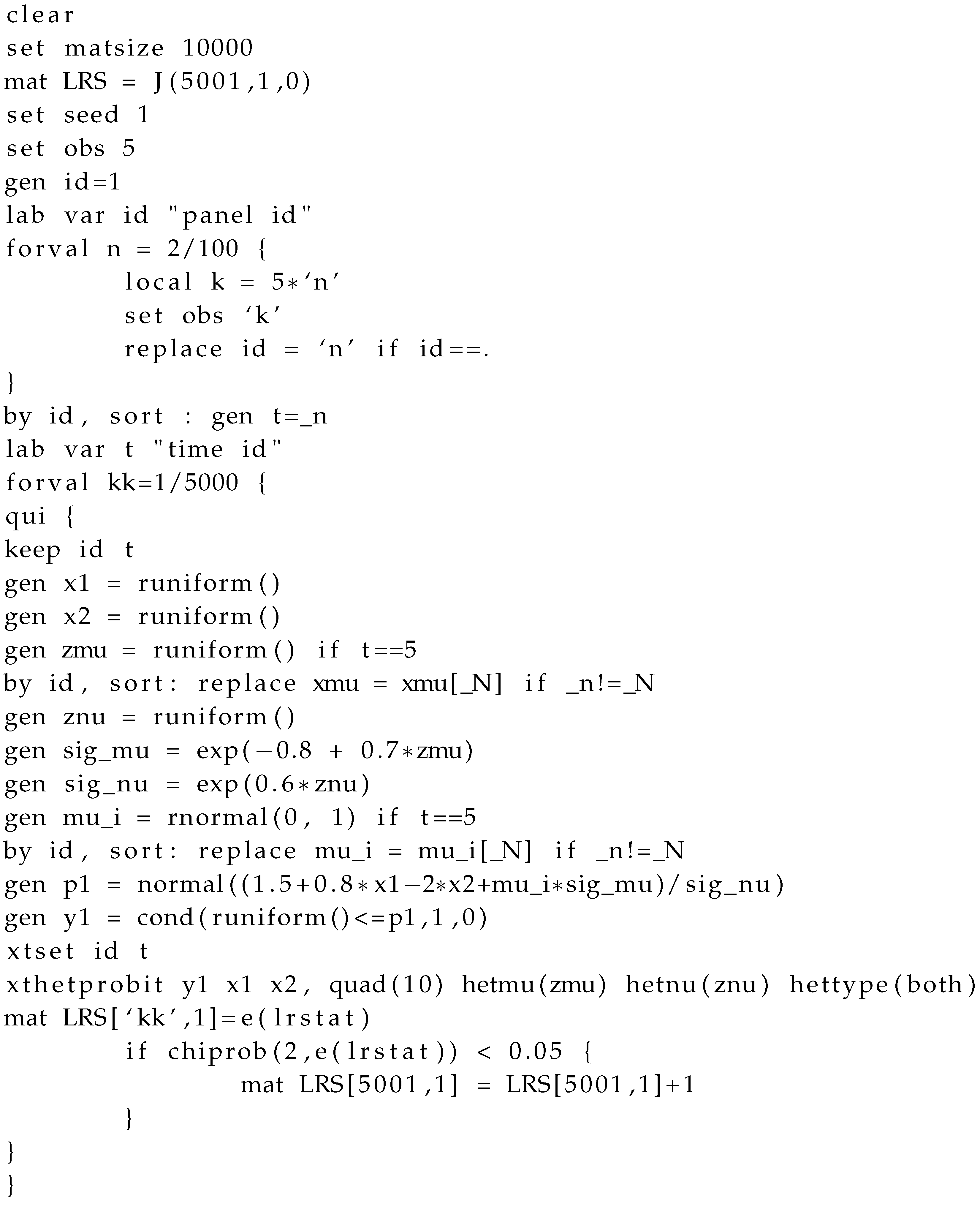

Appendix C. STATA Code for Monte Carlo Experiments

Appendix D. Power of the Test for Different Degrees of Heteroskedasticity

Appendix D.1. Testing for the Joint Hypothesis

Table A1.

Power and size of the LR test based on 5000 replications: case of .

Table A1.

Power and size of the LR test based on 5000 replications: case of .

| Setting | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 4.48 | 4.88 | 4.44 | 5.42 | 5.58 | 5.52 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| 0 | 1 | 12.68 | 91.24 | 99.48 | 100 | 6.6 | 92.24 | 98.42 | 100 |

| 0 | 2 | 35.88 | 99.92 | 100 | 100 | 31.84 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 0 | 3 | 50.22 | 99.94 | 100 | 100 | 38.42 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 1 | 0 | 22.08 | 39.08 | 99.48 | 100 | 13.36 | 29.3 | 98.46 | 100 |

| 1 | 1 | 26.56 | 97.56 | 100 | 100 | 14.46 | 90.04 | 99.6 | 100 |

| 1 | 2 | 46.36 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 49.26 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 1 | 3 | 45.78 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 62.56 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 0 | 30.79 | 72.34 | 100 | 100 | 21.08 | 43.12 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 1 | 54.14 | 99.26 | 100 | 100 | 23.08 | 75.34 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 2 | 78.28 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 65.62 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 3 | 79.28 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 87.06 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 0 | 50.92 | 73.8 | 100 | 100 | 30.08 | 58.46 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 1 | 59.52 | 96.88 | 100 | 100 | 37.72 | 56.46 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 2 | 90.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 57.88 | 99.92 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 3 | 95.46 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Appendix D.2. Testing for the Marginal Hypothesis of No Heteroskedasticity in Individual Effects Given Homoskedastic Idiosyncratic Errors

Table A2.

Power and size of the LR test based on 5000 replications: case of .

Table A2.

Power and size of the LR test based on 5000 replications: case of .

| Setting | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.26 | 5.46 | 5.06 | 5.02 | 4.42 | 5.08 | 4.76 | 4.72 | |

| 1 | 24.86 | 47.12 | 99.54 | 100 | 5.88 | 15.76 | 77.84 | 98.68 | |

| 2 | 35.16 | 71.7 | 100 | 100 | 6.22 | 17.68 | 90.52 | 100 | |

| 3 | 29.14 | 64.98 | 100 | 100 | 4.94 | 15.28 | 99.32 | 100 | |

| 0 | 5.26 | 5.46 | 5.06 | 5.02 | 4.42 | 5.08 | 4.76 | 4.72 | |

| 1 | 5.78 | 5.46 | 5.56 | 4.74 | 5.06 | 4.82 | 4.72 | 4.4 | |

| 2 | 5.26 | 5.06 | 5.58 | 4.46 | 5.56 | 4.62 | 5.02 | 4.42 | |

| 3 | 5.12 | 4.94 | 4.96 | 4.44 | 5.44 | 4.74 | 4.92 | 4.42 | |

| 0 | 0 | 5.26 | 5.46 | 5.06 | 5.02 | 4.42 | 5.08 | 4.76 | 4.72 |

| 0 | 1 | 5.78 | 5.46 | 5.56 | 4.74 | 5.06 | 4.82 | 4.72 | 4.4 |

| 0 | 2 | 5.26 | 5.06 | 5.58 | 4.46 | 5.56 | 4.62 | 5.02 | 4.42 |

| 0 | 3 | 5.12 | 4.94 | 4.96 | 4.44 | 5.44 | 4.74 | 4.92 | 4.42 |

| 1 | 0 | 24.86 | 47.12 | 99.54 | 100 | 5.88 | 15.76 | 77.84 | 98.68 |

| 1 | 1 | 27.2 | 53.2 | 99.6 | 100 | 15.66 | 34.26 | 96.3 | 100 |

| 1 | 2 | 23.88 | 45.78 | 97.2 | 100 | 22.56 | 42.84 | 98.64 | 100 |

| 1 | 3 | 14 | 33.56 | 79.58 | 100 | 19.08 | 31.72 | 92.44 | 100 |

| 2 | 0 | 35.16 | 71.7 | 100 | 100 | 6.22 | 17.68 | 90.52 | 100 |

| 2 | 1 | 59.46 | 91.98 | 100 | 100 | 24.76 | 59.52 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 2 | 67 | 94.98 | 100 | 100 | 55.48 | 89.68 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 3 | 52.72 | 89.16 | 100 | 100 | 55.9 | 88.36 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 0 | 29.14 | 64.98 | 100 | 100 | 4.94 | 15.28 | 99.32 | 100 |

| 3 | 1 | 66.46 | 95.96 | 100 | 100 | 21.56 | 59.06 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 2 | 88.42 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 65.1 | 97.06 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 3 | 86.9 | 99.66 | 100 | 100 | 83.36 | 99.58 | 100 | 100 |

Appendix D.3. Testing for the Marginal Hypothesis of no Heteroskedasticity in Idiosyncratic Errors Given Homoskedastic Individual Effects

Table A3.

Power and size of the LR test based on 5000 replications: case of .

Table A3.

Power and size of the LR test based on 5000 replications: case of .

| Setting | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.64 | 4.48 | 4.44 | 5.1 | 5.56 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | |

| 1 | 20.5 | 95.6 | 99.8 | 100 | 11.12 | 96.62 | 99.5 | 100 | |

| 2 | 54.28 | 99.98 | 100 | 100 | 52.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| 3 | 66.18 | 99.96 | 100 | 100 | 62.46 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| 0 | 4.64 | 4.48 | 4.44 | 5.1 | 5.56 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | |

| 1 | 6.6 | 8.2 | 39.06 | 43.18 | 23.96 | 23.98 | 87.02 | 96.4 | |

| 2 | 16.08 | 23.78 | 77.06 | 96.1 | 15.54 | 34.34 | 99.96 | 99.42 | |

| 3 | 25.28 | 29.19 | 97.98 | 98.72 | 24.58 | 49.7 | 99.96 | 100 | |

| 0 | 0 | 4.64 | 4.48 | 4.44 | 5.1 | 5.56 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| 0 | 1 | 20.5 | 95.6 | 99.8 | 100 | 11.12 | 96.62 | 99.5 | 100 |

| 0 | 2 | 54.28 | 99.98 | 100 | 100 | 52.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 0 | 3 | 66.18 | 99.96 | 100 | 100 | 62.46 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 1 | 0 | 6.6 | 8.2 | 39.06 | 43.18 | 23.96 | 23.98 | 87.02 | 96.4 |

| 1 | 1 | 11.52 | 96.46 | 99.54 | 100 | 34.2 | 87.7 | 84.38 | 100 |

| 1 | 2 | 50.92 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 53.16 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 1 | 3 | 60.96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 76.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 0 | 16.08 | 23.78 | 77.06 | 96.1 | 15.54 | 34.34 | 99.96 | 99.42 |

| 2 | 1 | 24.22 | 86.38 | 91.18 | 100 | 25.24 | 50.28 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 2 | 45.94 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 34.06 | 99.98 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 3 | 70.08 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 78.88 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 0 | 25.28 | 29.19 | 97.98 | 98.72 | 24.58 | 49.7 | 99.96 | 100 |

| 3 | 1 | 33.71 | 56.64 | 98.04 | 99.92 | 32.36 | 59.6 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 2 | 48.88 | 99.98 | 100 | 100 | 51.34 | 99.32 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 3 | 67.52 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 65.98 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Appendix E. Application and Comparisons

Appendix E.1. Application and Comparison for Data Generated with Individual Effects Heteroskedastic

Table A4.

Estimated index function and variance parameters.

Table A4.

Estimated index function and variance parameters.

| Variables | Homoskedastic | Heteroskedastic | Heteroskedastic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel Probit | Pooled Probit | Panel Probit | ||

| With | ||||

| *** | 6.2328 ** | |||

| The estimated index function parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| The variance parameters. | ||||

| *** | ** | |||

| *** | *** | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| With | ||||

| *** | *** | |||

| The estimated index function parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| The variance parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | |||

| *** | *** | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

95% level confident interval in brackets; ***: Significant at the 1% level. **: Significant at the 5% level.

Appendix E.2. Application and Comparison for Data Generated with Idiosyncratic Errors Heteroskedastic

Table A5.

Estimated index function and variance parameters.

Table A5.

Estimated index function and variance parameters.

| Variables | Homoskedastic | Heteroskedastic | Heteroskedastic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel Probit | Pooled Probit | Panel Probit | ||

| With | ||||

| 5.99 ** | *** | |||

| The estimated index function parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| The variance parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | |||

| *** | *** | |||

| With | ||||

| *** | *** | |||

| The estimated index function parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| The variance parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | |||

| *** | *** | |||

95% level confident interval in brackets; ***: Significant at the 1% level. **: Significant at the 5% level.

Appendix E.3. Application and Comparison for Data Generated with Both Individual Effects and Idiosyncratic Heteroskedastic

Table A6.

Estimated index function and variance parameters.

Table A6.

Estimated index function and variance parameters.

| Variables | Homoskedastic | Heteroskedastic | Heteroskedastic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel Probit | Pooled Probit | Panel Probit | ||

| With | ||||

| *** | *** | |||

| The estimated index function parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| The variance parameters. | ||||

| ** | ||||

| *** | *** | |||

| *** | *** | |||

| With | ||||

| *** | *** | |||

| The estimated index function parameters. | ||||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | ||

| The variance parameters. | ||||

| * | *** | |||

| *** | *** | |||

| *** | *** | |||

95% level confident interval in brackets; ***: Significant at the 1% level. **: Significant at the 5% level. *: Significant at the 10% level.

Appendix F. Estimates for Different Numbers of Quadrature Points

Table A7.

Changes in Parameters and in log-likelihood with respect to the number of quadrature point Q.

Table A7.

Changes in Parameters and in log-likelihood with respect to the number of quadrature point Q.

| Variables | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| 41 | 53 | 62 | 79 | 96 | 106 | 130 | 133 |

95% level confident interval in brackets; ***: Significant at the 1% level. denotes the relative difference defined as . It is calculated to assess the variation in the log-likelihood (), and parameters when the number of quadrature points Q increases. is calculated as the maximum relative difference between parameters for two different Q.

References

- Baltagi, Badi H. 1988. An alternative heteroscedastic error component model, problem 88.2.2. Econometric Theory 4: 349–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, Badi H. 2008. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data, 4th ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Baltagi, Badi H., Georges Bresson, and Alain Pirotte. 2006. Joint lm test for homoskedasticity in a one-way error component model. Journal of Econometrics 134: 401–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bland, James R., and Amanda C. Cook. 2018. Random effects probit and logit: understanding predictions and marginal effects. Applied Economics Letters 26: 116–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Russell, and James G. MacKinnon. 1984. Convenient specification tests for logit and probit models. Journal of Econometrics 25: 241–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, William, Jeffrey Pitblado, and William Sribney. 2010. Maximum Likelihood Estimation With Stata, 4th ed. College Station: Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, William H. 2012. Econometric Analysis, 7th ed. Upper Saddle Rive: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, William H. 2018. Econometric Analysis, 8th ed. New York: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, John, and John DiNardo. 2001. Econometric Methods, 4th ed. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, Tony. 2000. The incidental parameter problem since 1948. Journal of Econometrics 95: 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, Michael. 1995. Some specification tests for probit models estimated on panel data. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 13: 475–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Qing, and Donald A. Pierce. 1994. A note on gauss-hermite quadrature. Biometrika 83: 624–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazodier, Pascal, and Alain Trognon. 1978. Heteroskedasticity and stratification in error components models. Annales de l’INSEE 30: 451–82. [Google Scholar]

- Montes-Rojas, Gabriel, and Walter Sosa-Escudero. 2011. Robust tests for heteroskedasticity in the one-way error components model. Journal of Econometrics 160: 300–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, Richard, and Eric Delattre. 2018. On the estimation of causality in a bivariate dynamic probit model on panel data with stata software. a technical review. Theoretical Economics Letters 8: 1257–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, Jennifer C., and Adrian F. M. Smith. 1982. Applications of a method for the efficient computation of posterior distributions. Applied Statistics 31: 214–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, William C. 1988. A transformation for heteroscedastic error components regression models. Economics Letters 27: 349–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbon, Harrie. 1980. Testing for heteroscedasticity in a model of seemingly unrelated regression equations with variance components. Economics Letters 5: 149–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansbeek, Tom. 1989. An alternative heteroscedastic error components model, solution 88.1.1. Econometric Theory 5: 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. 2001. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | A user-written Stata’s ado file is provided to deal with these purposes. This ado file is an extension of the existing Stata’s and commands that accounts for each of the types of heteroskedasticity observed in panel one-way error component models in the literature. A Stata code for computing the marginal effects after the proposed estimation procedure is given in the Appendix A. |

| 2. | The estimation procedure described above has been implemented as a Stata user-written ado file using the Stata’s procedure for maximum likelihood estimation (see Gould et al. 2010; Moussa and Delattre 2018). |

| 3. | For all others applications presented herein, is used as the number of quadrature points. |

| 4. | An example of the Stata code for the experiment of the power of the test in presence of heteroskedasticity due to both and with and is provided in the Appendix C. The Appendix B reports the Stata code used to generate the data. |

| 5. | The empirical size estimated on 5000 replications is significantly different from the nominal size of 5% if it does not range between 4.4% and 5.6%. These thresholds are calculated as . |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).