1. Introduction

The delisting of Binance USD (BUSD), a leading USD-pegged stablecoin

Cole (

2024), represents a significant milestone in the advancement of cryptocurrency regulation and highlights the increasing scrutiny that U.S. regulatory authorities are directing toward stablecoin issuers

Lunde (

2023). BUSD, issued by Paxos Trust Company and branded by Binance, recognized as the largest cryptocurrency exchange globally by trading volume

Wilmarth (

2023), exemplifies the intricate dynamics between conventional financial regulation and innovative digital assets

Duan and Urquhart (

2023).

The regulatory actions against BUSD have emerged within a broader framework of intensified oversight following the collapse of Terra/LUNA and FTX in 2022

Trautman et al. (

2024). These incidents prompted heightened attentiveness from regulatory bodies concerning the operational frameworks of stablecoins and their associated systemic risks

Goforth (

2023). In February 2023, the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) mandated that Paxos cease the minting of new BUSD tokens, citing unresolved issues regarding Paxos’s oversight of its relationship with Binance, as well as concerns related to Binance’s comprehensive compliance framework

Zijing (

2023).

This regulatory intervention signifies a fundamental shift in the stance of U.S. authorities concerning stablecoin governance, accentuating the critical necessity for robust compliance mechanisms and transparent operational structures

Dell’Erba (

2023). The actions taken against BUSD particularly underscore regulators’ growing apprehension regarding the potential use of stablecoins in facilitating illicit financial activities, which underscores the need for enhanced Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) protocols

Skinner (

2023).

Subsequent legal proceedings involving Changpeng Zhao (CZ), the CEO of Binance, further complicate the discourse surrounding BUSD’s delisting

Qiǎn (

2023). The criminal charges and the substantial settlement reached with U.S. authorities in late 2023 have raised fundamental questions pertaining to the intersection of centralized exchange operations and regulatory compliance

Gushterov (

2023). This development, in conjunction with the delisting of BUSD, represents a pivotal moment in the structural and governance framework of the cryptocurrency market

Aujus (

2023).

A critical inquiry arises regarding the broader implications of the delisting of BUSD for the stablecoin ecosystem: To what extent does this regulatory action alter the competitive dynamics among remaining stablecoin issuers, and what are the implications for market concentration within the stablecoin sector? Initial market data indicates a significant redistribution of liquidity toward alternative stablecoins, particularly Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC). This consolidation prompts essential considerations regarding systemic risk and market power within the digital asset ecosystem

Bains et al. (

2022).

The growing prominence of stablecoins has reignited debates about their implications for financial stability and systemic risk. Systemic risk, broadly defined as the risk of disruptions in the financial system with severe consequences for the real economy

Acharya et al. (

2017), has increasingly been applied to the digital asset space. Recent research highlights the potential fragility of stablecoin arrangements and their spillover channels. For example,

Giudici et al. (

2022) analyze basket-based stablecoins and show how diversification mechanisms may mitigate, but also propagate, risks across tokens.

R. Ahmed and Aldasoro (

2025) further demonstrate that stablecoin dynamics can directly affect the pricing of traditional safe assets, underscoring their growing relevance for mainstream financial markets. More broadly,

Aquilina et al. (

2025) stress that cryptocurrencies and decentralized finance (DeFi) introduce novel functions that, while fostering innovation, also pose new challenges for financial stability.

Against this backdrop, our paper examines the repercussions of the BUSD delisting episode, focusing on its impact on the dynamics of competing stablecoins. By employing a local projections framework, we contribute to the literature on stablecoins’ systemic role, while providing empirical evidence on substitution and spillover effects that have direct policy relevance.

Furthermore, the case of BUSD’s delisting presents a compelling research question concerning the role of regulatory actions in shaping market structure: Does increased regulatory scrutiny of major market participants inevitably lead to greater concentration among a smaller number of compliant entities, thereby potentially engendering new forms of systemic risk? This paradox warrants thorough examination from both regulatory and economic perspectives.

The body of literature on stablecoins is expanding rapidly. Recent research by

Łęt et al. (

2023) explores the function of stablecoins as safe-haven assets amid cryptocurrency volatility. Utilizing spectral decomposition of variance for frequency-domain analysis, the study investigates the influence of shocks in assets such as Bitcoin and Ethereum on investor behavior in stablecoins. The analysis employs daily data from December 2017 to July 2022, encompassing significant stablecoins (e.g., Tether, USD Coin, Binance USD, DAI, Paxos, Huobi USD, and Gemini USD) alongside volatile cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and a composite index). The findings suggest that volatility shocks moderately affect stablecoin popularity over a period of up to three days, with negative returns and increased volatility prompting investors—especially smaller investors—to gravitate toward stablecoins, thereby highlighting their role in stabilizing markets during periods of financial uncertainty.

In a related investigation,

Galati and Capalbo (

2024) examined the ramifications of the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023 on cryptocurrency markets, with a focus on stablecoins. By applying a BEKK-GARCH multivariate model to minute-by-minute price data for Bitcoin and five major stablecoins (USDT, BUSD, USDC, DAI, and TUSD) over a 14-day period surrounding the bankruptcy, their analysis reveals significant volatility spillovers. Notably, when Circle announced that

$3.3 billion of USDC reserves were trapped in Silicon Valley Bank, marked market reactions occurred: USDC and DAI experienced substantial declines in price, and TUSD lost nearly 3% of its value, while BUSD and USDT traded at a premium. Increasing trading volumes further indicate a flight to safety towards more established stablecoins such as USDT.

With regard to the role of stablecoins as “anchors” within cryptocurrency markets,

Palazzi et al. (

2025) presents a comprehensive analysis of their stability, independence, and resilience. Employing asymmetric dynamic conditional correlation (ADCC)-GARCH models, Granger causality tests, and transfer entropy measures, the study evaluates data from major stablecoins (Tether, USD Coin, Binance USD), unpegged cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin, Ethereum, Binance Coin), and fiat currencies (EUR, JPY, GBP). The research uncovers significant vulnerabilities in stablecoin performance. Through methodical econometric analysis of liquidity conditions and market dynamics—particularly during adverse events such as the Terra-Luna collapse, as previously examined by

Diop (

2024),

Diop et al. (

2024) —these studies conclude that stablecoins’ susceptibility to market pressures and external shocks challenges their assumed role as stable monetary instruments, bearing critical implications for investors, policymakers, and regulators in the evolving cryptocurrency ecosystem.

Recent work has emphasized the importance of nonlinear and state-dependent dynamics in cryptocurrency markets.

Dimitriadis et al. (

2025), for instance, employ quantile-based and volatility models to study heterogeneous spillover effects across market conditions, showing that transmission mechanisms differ markedly between normal and stress periods. This focus on state dependence is closely related to our approach, which allows for asymmetric responses to regulatory shocks through linear and nonlinear Local Projections.

While

Dimitriadis et al. (

2025) analyze endogenous spillovers and volatility transmission across global cryptocurrency markets, our study focuses on the effects of a discrete regulatory intervention—the BUSD delisting—and its implications for liquidity reallocation and market structure within the stablecoin ecosystem. In this sense, the two approaches are complementary: their results highlight heterogeneity across market states, whereas our analysis documents how a targeted regulatory shock propagates through stablecoin and cryptocurrency markets over time.

Recent findings accentuate the increasing interdependence between traditional banking and cryptocurrency markets, providing critical insights for academics, practitioners, and policymakers who are concerned with systemic risk. While the study primarily addresses highly liquid digital assets, it establishes a foundation for further examination of financial contagion mechanisms that exist between conventional finance and digital assets.

To investigate the BUSD delisting, this paper employs the Local Projections approach, a method first introduced by

Jordà (

2005). Local projections represent an alternative technique for estimating impulse responses without the necessity of specifying and estimating a comprehensive multivariate dynamic system, such as a vector autoregression (VAR). Rather than depending on a global model, local projections derive impulse responses directly at each forecast horizon through a series of linear regressions, thereby enhancing robustness to model misspecification. This methodology permits more straightforward estimation through standard regression techniques, accommodates flexible nonlinear specifications, and facilitates analytical inference without the reliance on asymptotic approximations. Monte Carlo simulations and empirical applications validate the method’s advantages in accurately capturing impulse response dynamics, particularly within nonlinear and time-varying contexts.

Montiel Olea and Plagborg-Møller (

2021) significantly contribute to the academic discourse surrounding local projections by confirming their robustness and simplicity for impulse response inference. The authors illustrate that lag-augmented local projections, when combined with standard heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors, produce valid asymptotic inference consistently across both stationary and non-stationary data processes. This reliability persists as horizons extend proportionally with sample size

for

. This is in contrast to traditional autoregressive approaches, whose validity heavily relies on the persistence characteristics and horizon lengths involved. By establishing that lag augmentation eliminates the necessity for serial correlation adjustments in standard errors, this paper simplifies applied analyses while addressing significant weaknesses inherent in vector autoregression methods related to unit roots and identification. These theoretical advancements effectively resolve longstanding concerns regarding the inferential validity of local projections, thereby reinforcing their reputation as a robust alternative within structural macroeconomics.

Bruns and Lütkepohl (

2022) underscore the advantages of local projection (LP) estimators over conventional vector autoregression (VAR) models in structural macroeconomic analysis, particularly in proxy VAR frameworks. While impulse responses derived from VAR models depend on nonlinear transformations of estimated coefficients, LP estimators utilize direct linear regressions for each horizon, rendering them nonparametric and robust against model misspecification. This robustness is particularly significant when the actual data-generating process (DGP) diverges from a finite-order VAR structure, as LP estimators can mitigate biases stemming from incorrect lag specifications. The authors note that modified LP estimators—such as generalized least squares (GLSs) variants with lag augmentation—demonstrate enhanced small-sample performance, achieving lower root mean squared errors (RMSEs) compared to standard LP and VAR methods. For instance, a lag-augmented GLS estimator performs comparably to VAR estimators in larger samples, while maintaining computational simplicity and eliminating the necessity for extensive system estimation. Such features render LP methods particularly valuable for applied researchers who require reliable inference in environments characterized by model uncertainty.

The simulation study conducted by

Li et al. (

2024) provides essential insights into the bias-variance trade-offs between Local Projection (LP) and Vector Autoregression (VAR) methodologies for estimating structural impulse responses across numerous empirically calibrated macroeconomic data-generating processes (DGPs). The analysis indicates that LP estimators consistently display lower bias than VAR methodologies at both intermediate and long horizons, particularly when bias-correction techniques are employed. This characteristic is particularly valuable as LP methods avoid reliance on potentially misspecified VAR extrapolations. Utilizing DGPs constructed from a dynamic factor model fitted to 207 U.S. macroeconomic series, the authors replicate the complex persistence and cointegration patterns that are characteristic of real-world data. This strategy significantly enhances the external validity of their findings. Although LP methods may incur higher variance, particularly at extended horizons, their direct estimation approach is notably beneficial when researchers prioritize unbiased identification of impulse response shapes over precision. This consideration is especially pertinent in persistent macroeconomic systems, where restrictions on VAR lag length may induce substantial dynamic misrepresentation. Accordingly, these findings position LP as a highly compelling methodological alternative for structural macroeconometric analysis, warranting further investigation into bias correction and efficiency improvements in order to fully leverage its flexibility in capturing genuine economic dynamics.

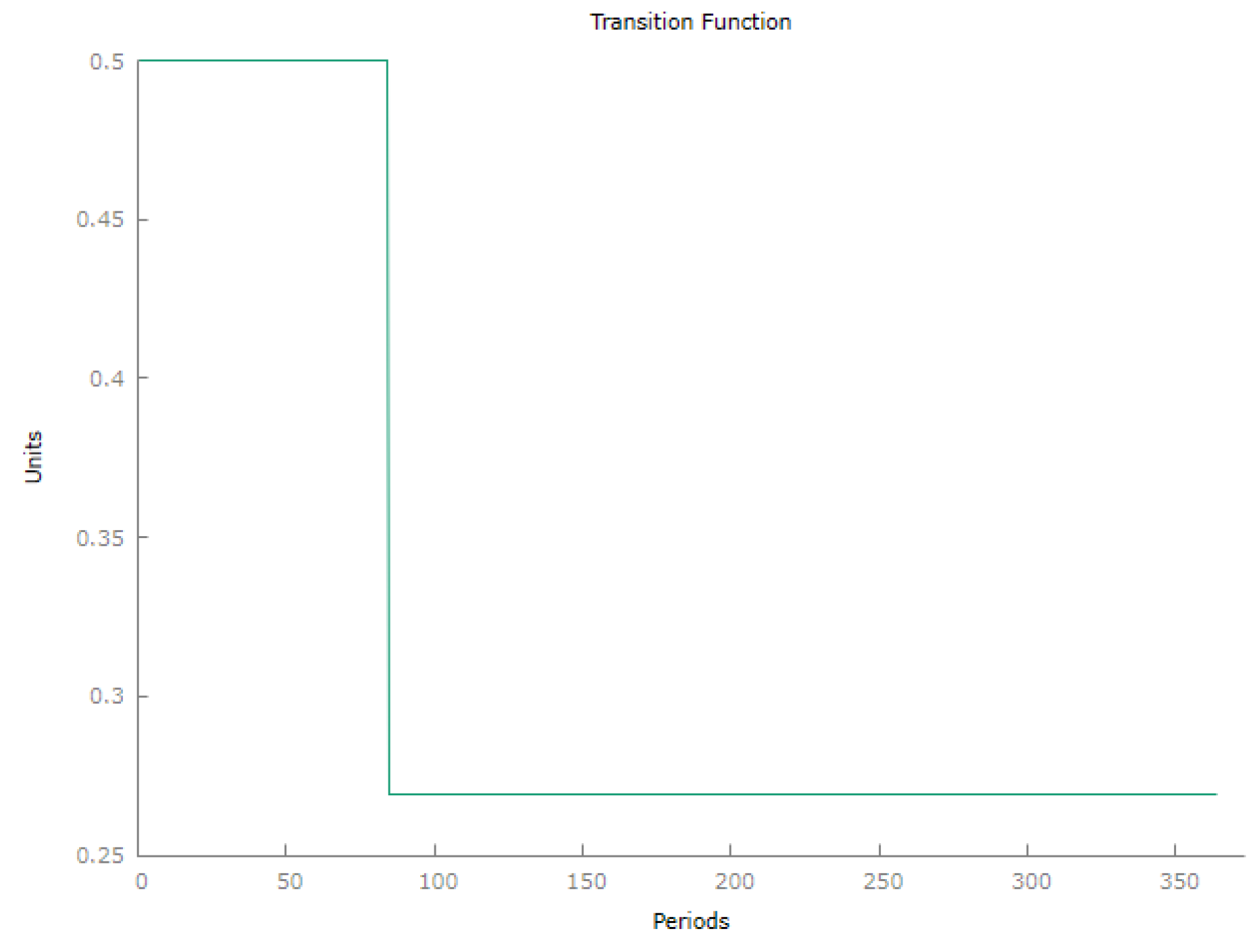

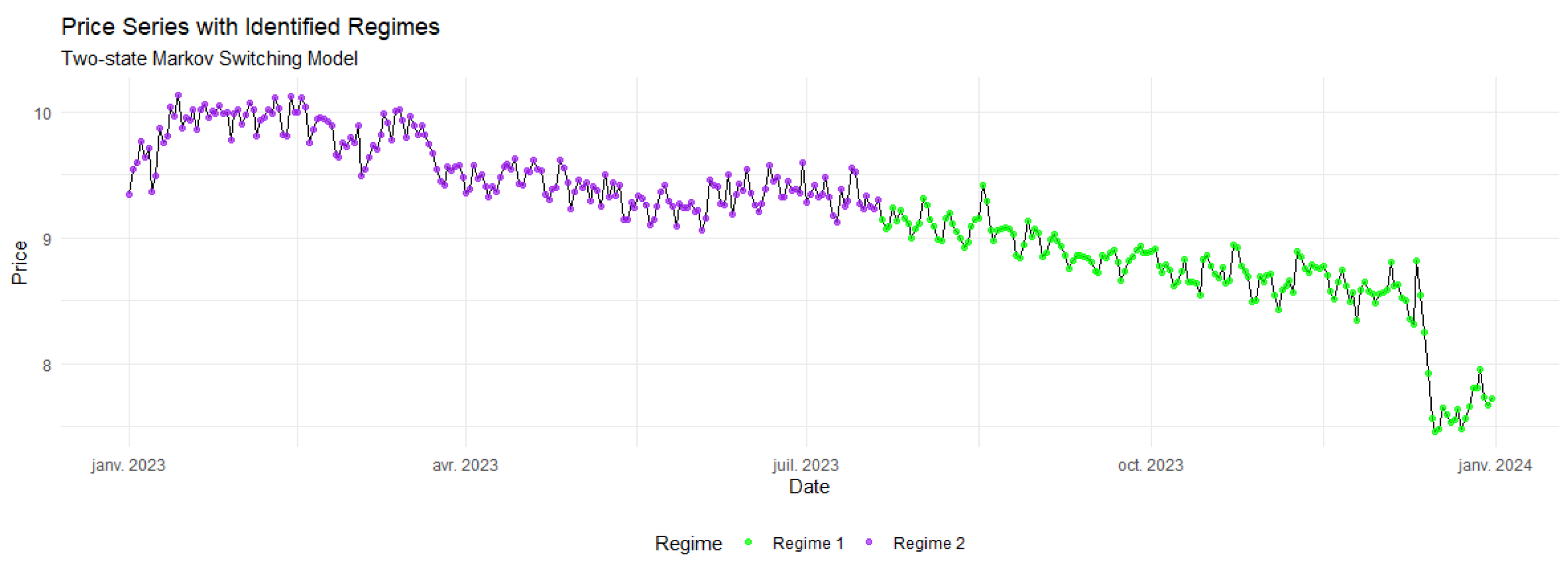

Furthermore, the study employs nonlinear local projections organized under a regime-switching representation, utilizing a dummy variable to specify the threshold differentiation.

M. I. Ahmed and Cassou (

2016) operationalize this technique to analyze the state-dependent effects of consumer confidence shocks on durable goods spending. By incorporating NBER business cycle dates to create regime-switching dummies, they delineate asymmetric responses: confidence shocks substantially influence durable goods spending during expansive periods (consistent with news-driven expectations) but have negligible effects during recessive periods (which align with animal spirits theory). The nonlinear local projections model, augmented with a threshold dummy variable, establishes a flexible and robust framework for examining state-dependent economic dynamics. By accommodating regime-specific responses to shocks, this model adeptly captures the differential effects of the variables under investigation during various phases of the business cycle. This methodological approach may prove particularly advantageous in documenting the impact of BUSD delisting on other stablecoins, depending on the relevant regime.

In accordance with the Markov-switching approach,

Gonçalves et al. (

2024) advocate that a state-dependent approach to local projections (LPs) presents a valuable method for estimating the dynamic responses of macroeconomic variables to shocks, particularly in contexts characterized by nonlinearities across different economic states (e.g., recession versus expansion). This approach is advantageous due to its computational simplicity when compared to more complex models, such as state-dependent structural VARs, which necessitate detailed specifications for state transitions. State-dependent LP estimates facilitate the differentiation of impulse responses across varying economic states without the necessity to directly model state transition processes, thus rendering the methodology more flexible and user-friendly. However, the effectiveness of this approach is contingent upon whether the economic state is exogenous or endogenous to macroeconomic shocks. In scenarios where the state is exogenous, the method reliably estimates both conditional average and marginal responses to shocks. Conversely, if the state is endogenous, particularly in the presence of substantial shocks, the LP estimator may be biased. This underscores the critical importance of meticulously considering the magnitude of shocks and the nature of state dependence when employing this technique.

In a related nonlinear methodology for Local Projections,

Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (

2012) establish a framework for estimating state-dependent fiscal multipliers through the application of Smooth-Transition VAR (STVAR) and direct projection methods.

The delisting of Binance USD (BUSD) signifies a critical regulatory intervention with extensive implications for the stablecoin ecosystem. This study illustrates that the liquidity displaced from BUSD predominantly reallocates to centralized, fiat-backed stablecoins, specifically Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC), thereby reinforcing their supremacy as systemic anchors. This swift redistribution highlights the market’s preference for liquidity depth and regulatory compliance; however, it simultaneously increases concentration risks, rendering the ecosystem susceptible to shocks affecting these limited entities. In contrast, algorithmic and decentralized stablecoins, such as DAI and FRAX, exhibit limited capacity to absorb this displaced liquidity, indicative of market skepticism regarding their stabilization mechanisms during periods of crisis. Their hybrid frameworks, whether crypto-collateralized or algorithmic, fail to instill confidence, underscoring the limitations inherent in non-fiat-backed designs with respect to accommodating systemic liquidity shocks.

Regarding traditional cryptocurrencies, the delisting induces asymmetric effects: Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum (ETH) encounter temporary liquidity contractions due to the disruption of trading pairs and decentralized finance (DeFi) activities resulting from stablecoin instability. Nevertheless, their long-term resilience underscores their dual role as speculative assets and essential liquidity reservoirs. Smaller cryptocurrencies, such as TRX, experience only momentary spikes in demand, failing to serve as sustainable alternatives. These dynamics illustrate the interconnectedness between stablecoins and the broader cryptocurrency market, wherein disruptions in stablecoins may induce short-term volatility without fundamentally destabilizing well-established assets such as BTC or ETH.

This research suggests a potential paradox: an increase in regulatory scrutiny directed at major players may lead to enhanced concentration among a smaller number of compliant entities, thereby potentially engendering new forms of systemic risk. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the intricate interplay between regulatory actions, market dynamics, and systemic risks within the evolving landscape of stablecoins and cryptocurrencies.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows.

Section 2 details the linear and nonlinear Local Projection methods.

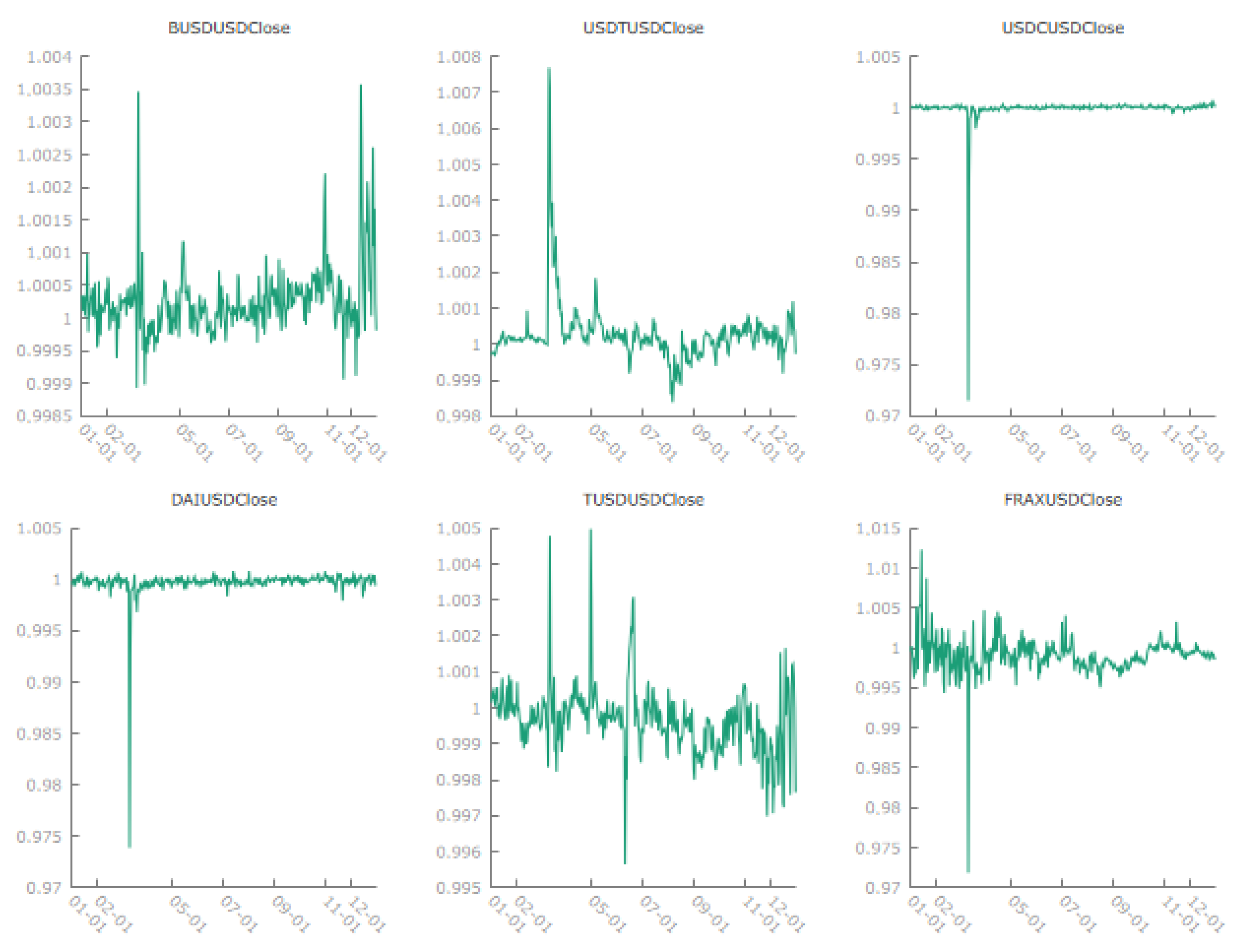

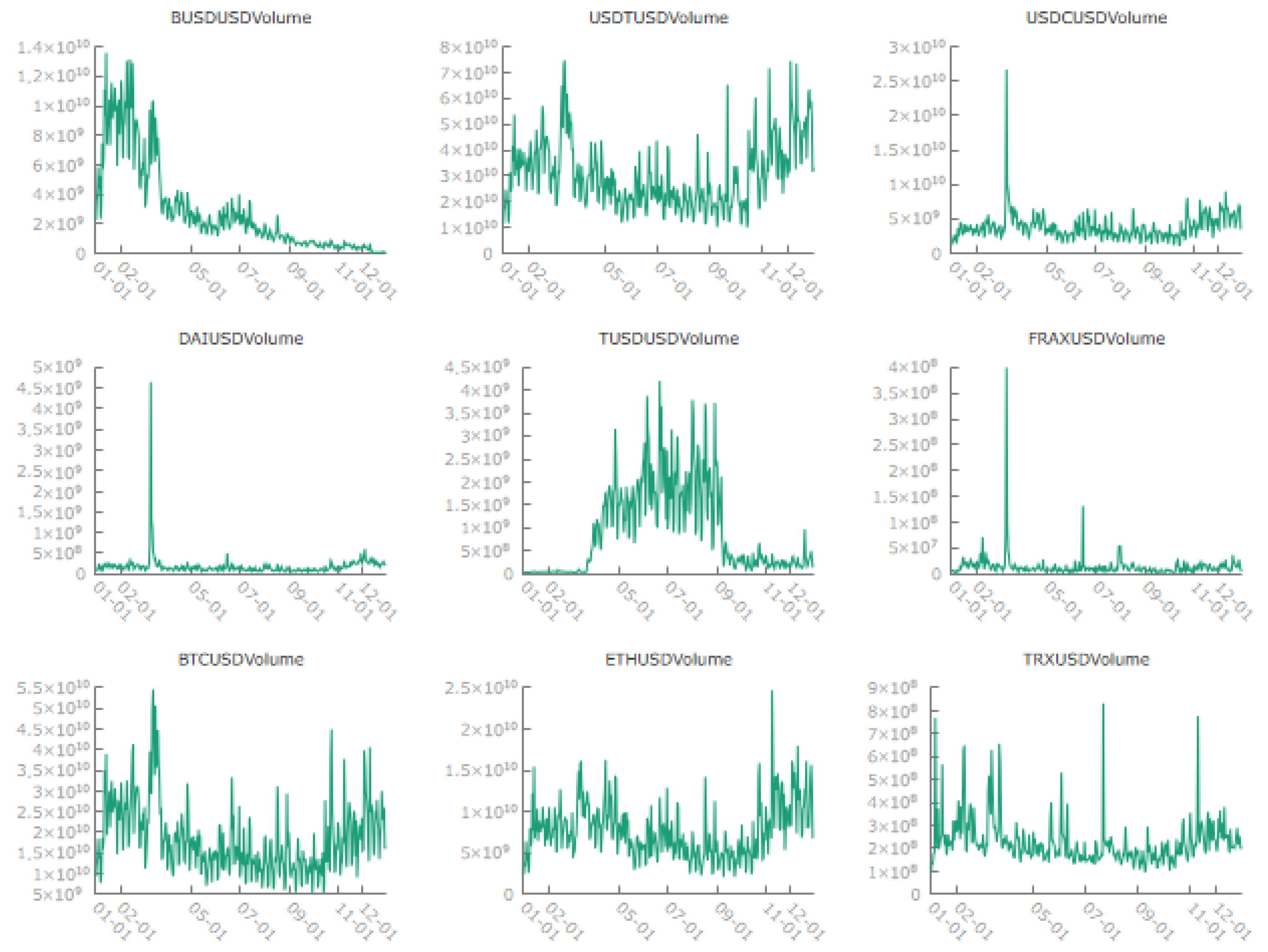

Section 3 presents the BUSD and other associated stablecoins under study, both in prices and volumes.

Section 4 contains the Local Projections results from the linear approach.

Section 5 adds the regime-switching nonlinear version of Local Projections.

Section 6 concludes.

4. Linear Local Projections

The econometric analysis is structured into three distinct steps. First, linear local projections are computed using price series expressed in logarithmic form. Second, we regenerate the linear local projections utilizing volume data, also in logarithmic form, to facilitate a comparative analysis of the results. Lastly, we introduce a VAR(1) model to serve as a benchmark for this study.

4.1. Linear Price Analysis

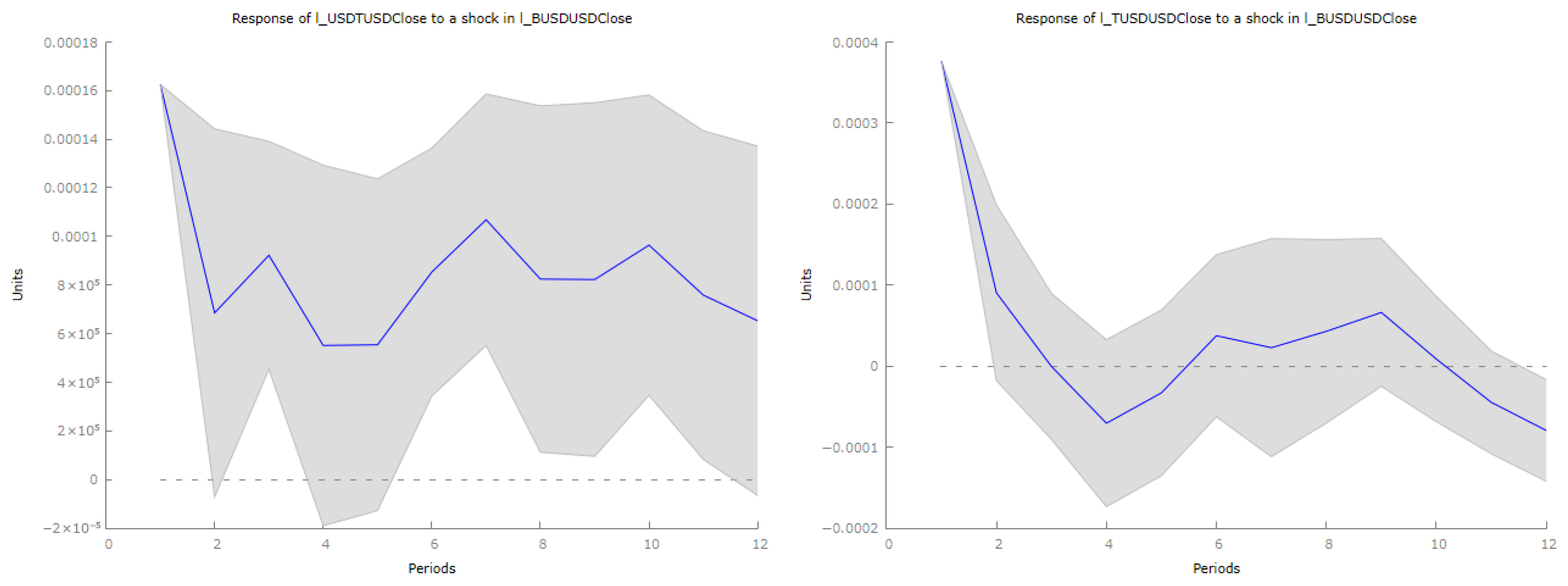

This section provides the estimated impulse response functions (IRFs) obtained through the Local Projections (LPs) method. The purpose of this analysis is to evaluate how the prices of key stablecoins in our dataset respond to a shock in the closing price of BUSD. The responses are examined over a 12-period horizon, and confidence intervals are included to illustrate the statistical significance of the results.

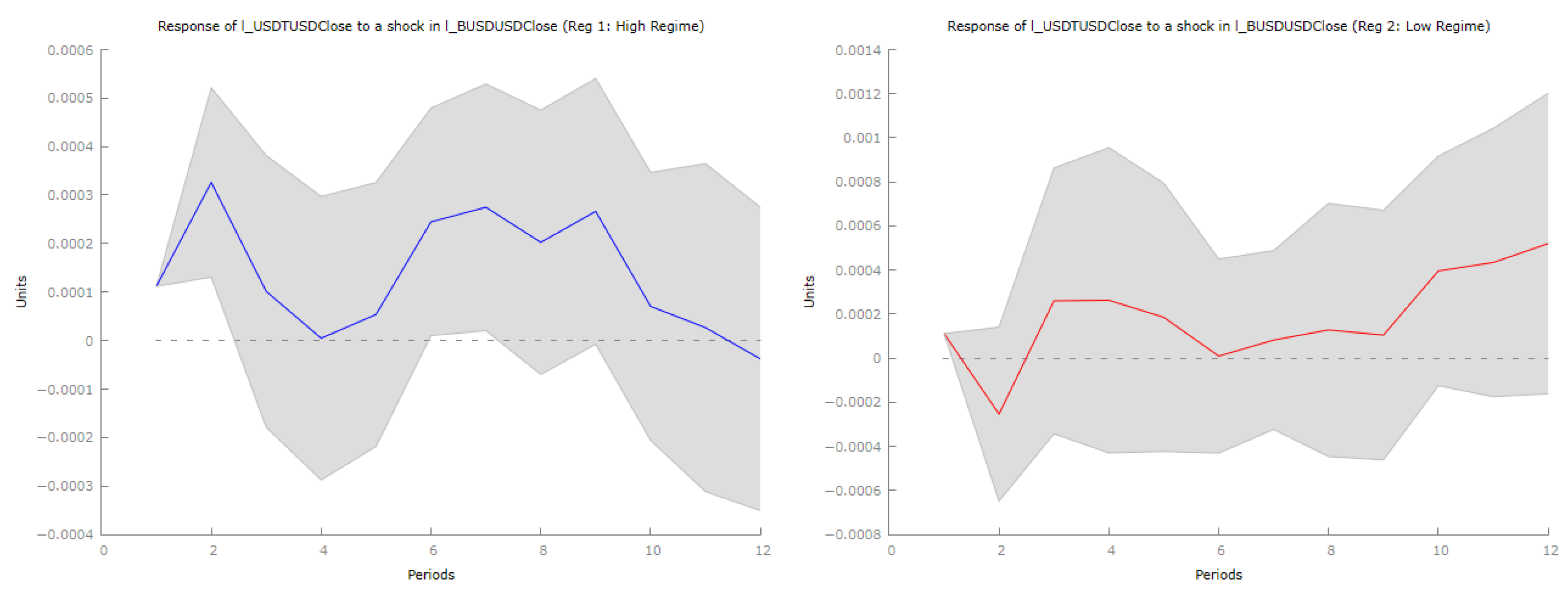

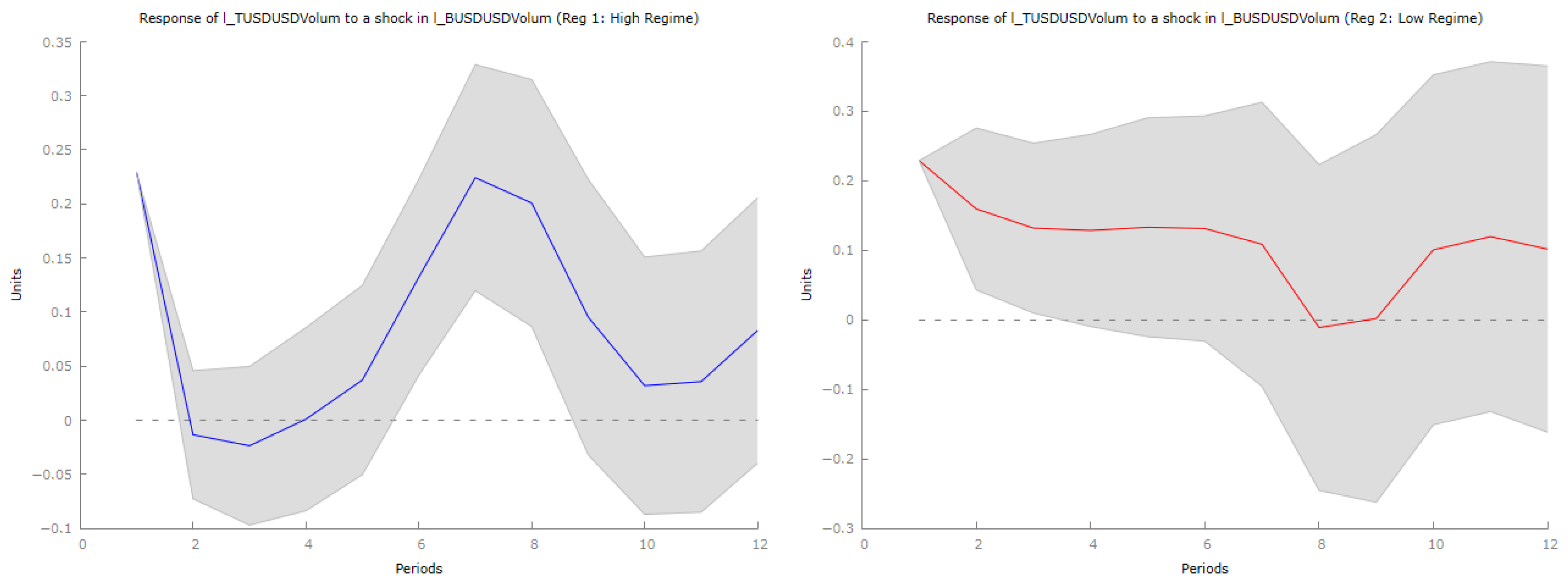

The impulse response functions illustrated in

Figure 4 reveal several significant patterns pertaining to the cross-elasticity of stablecoin prices, suggesting intricate interconnections within the digital currency ecosystem. Notably, USDT displays characteristics that align with the “flight-to-quality” phenomenon commonly observed in traditional financial markets. The immediate positive price elasticity (

) following a BUSD shock, in conjunction with rapid mean reversion, indicates a sophisticated market mechanism wherein temporary arbitrage opportunities are swiftly eliminated. This outcome is consistent with theoretical predictions derived from established market efficiency models within digital asset markets. The rapid attenuation of the effects (as time approaches zero following initial periods) provides empirical support for the hypothesis that dominant stablecoins possess robust price stability mechanisms, likely attributable to superior market depth and liquidity networks.

The response function of TUSD offers a compelling case study regarding the dynamics of second-tier stablecoins. The initial positive elasticity followed by a decay suggests a temporal hierarchy in cross-stablecoin substitution effects. This phenomenon can be interpreted through the lens of limited arbitrage capital theory, which posits that smaller market participants encounter constraints that limit their capacity for sustained capital reallocation. The parameters of the decay function imply that considerations of market depth supersede short-term substitution effects in establishing long-term equilibrium.

In

Figure 5, the response pattern of USDC is particularly noteworthy due to its non-monotonic features. The initial positive shock, followed by a negative adjustment phase, indicates the presence of complex feedback mechanisms within the stablecoin ecosystem. This finding challenges the prevailing assumption of uniform substitution effects among stablecoin pairs and suggests the possibility of strategic complementarities within digital asset markets. The observed pattern may be rationalized through a model of sequential portfolio rebalancing, whereby institutional investors optimize their holdings of stablecoins across various time horizons.

Concerning alternative cryptocurrencies, the findings for TRON merit careful consideration. The observed delayed positive response (approximately two weeks) suggests potential spillover effects within the trading ecosystem rather than direct price correlations. This temporal lag structure may reveal second-order effects emerging from market microstructure channels.

In

Figure 6, the absence of significant responses in FRAX, BTC, and ETH lends empirical support to the market segmentation hypothesis within cryptocurrency markets. This finding bears important implications for portfolio diversification strategies and indicates that the stablecoin market retains a degree of isolation from the broader dynamics of cryptocurrency prices.

These results contribute to a deeper understanding of price formation mechanisms in digital asset markets and suggest several avenues for future research, particularly regarding the role of market microstructure in influencing cross-asset price dynamics.

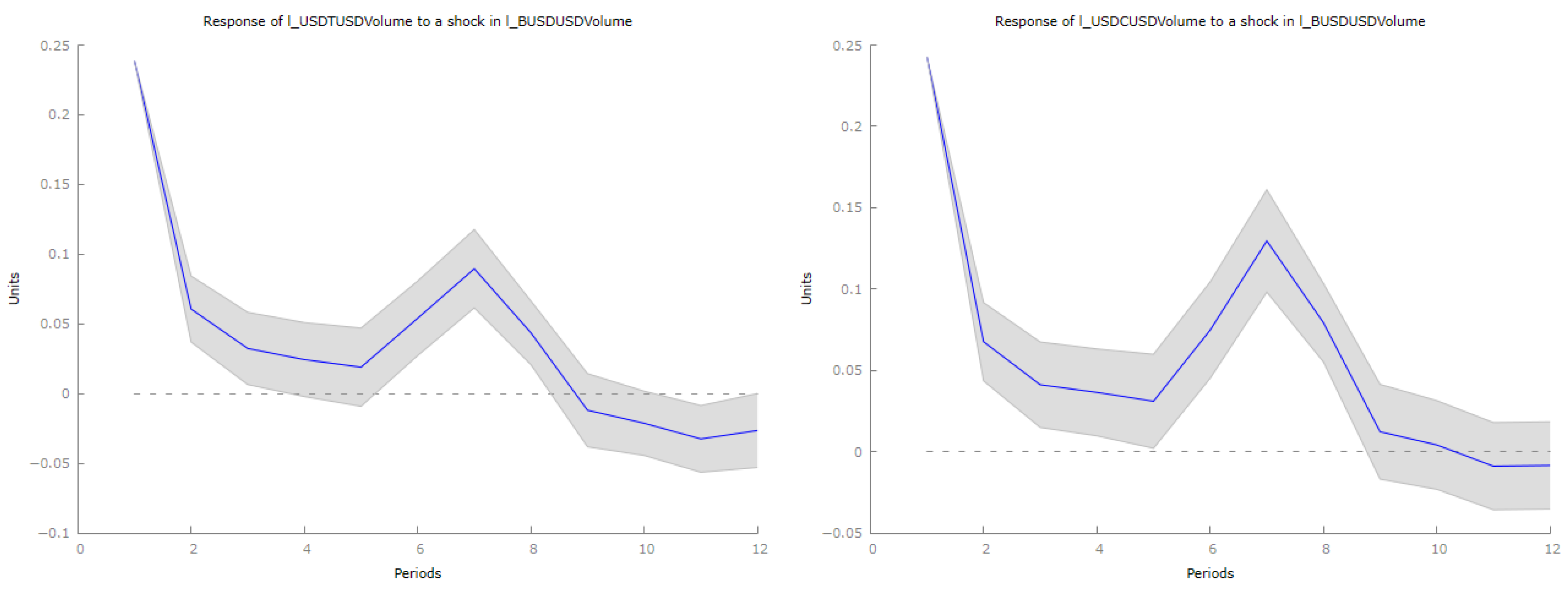

4.2. Linear Volume Analysis

This section examines the effects of BUSD volume shocks on the trading activity of major stablecoins and cryptocurrencies, employing a Vector Autoregression (VAR) framework. Analyzing volume dynamics offers valuable insights into how liquidity flows adjust in response to fluctuations in BUSD trading activity, thereby revealing potential substitution effects between stablecoins and spillover effects on the broader cryptocurrency markets. Given the essential role of stablecoins in facilitating market liquidity, understanding these volume interactions is critical for assessing the extent to which changes in BUSD trading influence the stability and liquidity of other digital assets. The findings underscore the significant roles of USDT and USDC in absorbing displaced liquidity, highlight the comparatively weaker responses of decentralized and algorithmic stablecoins, and illustrate the broader market implications for the trading activities of Bitcoin and Ethereum.

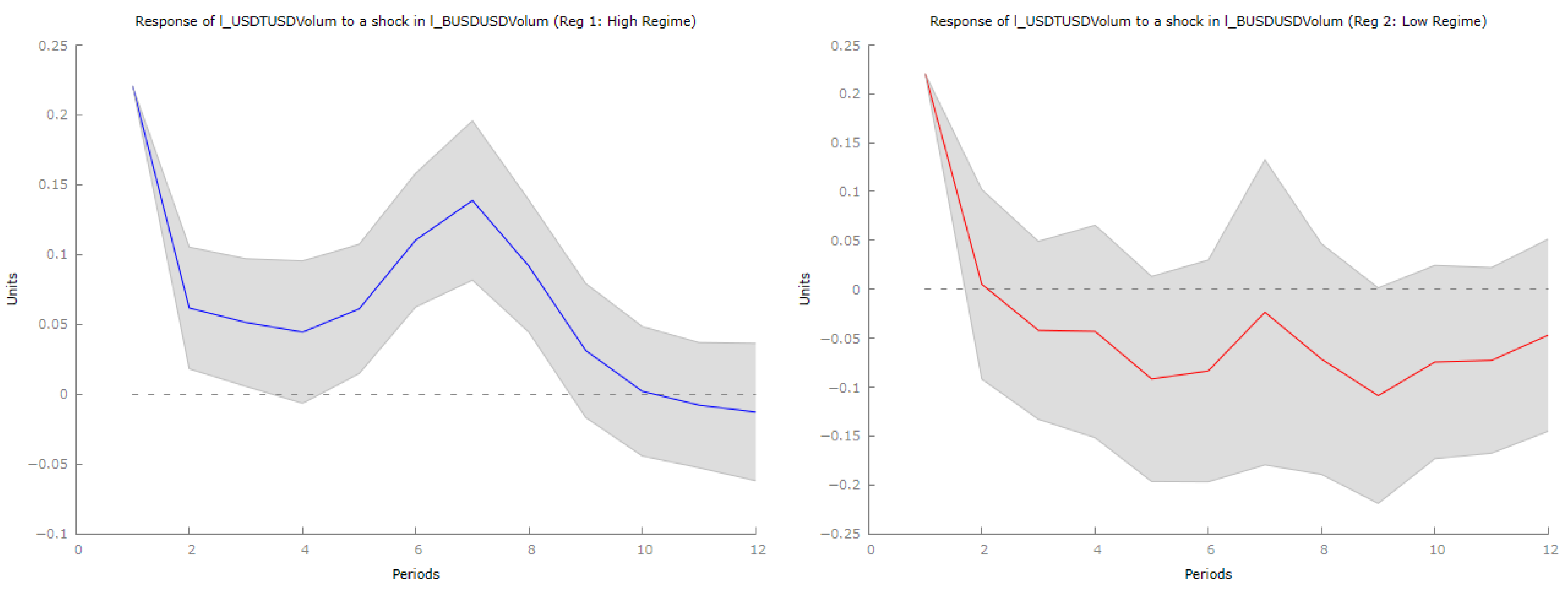

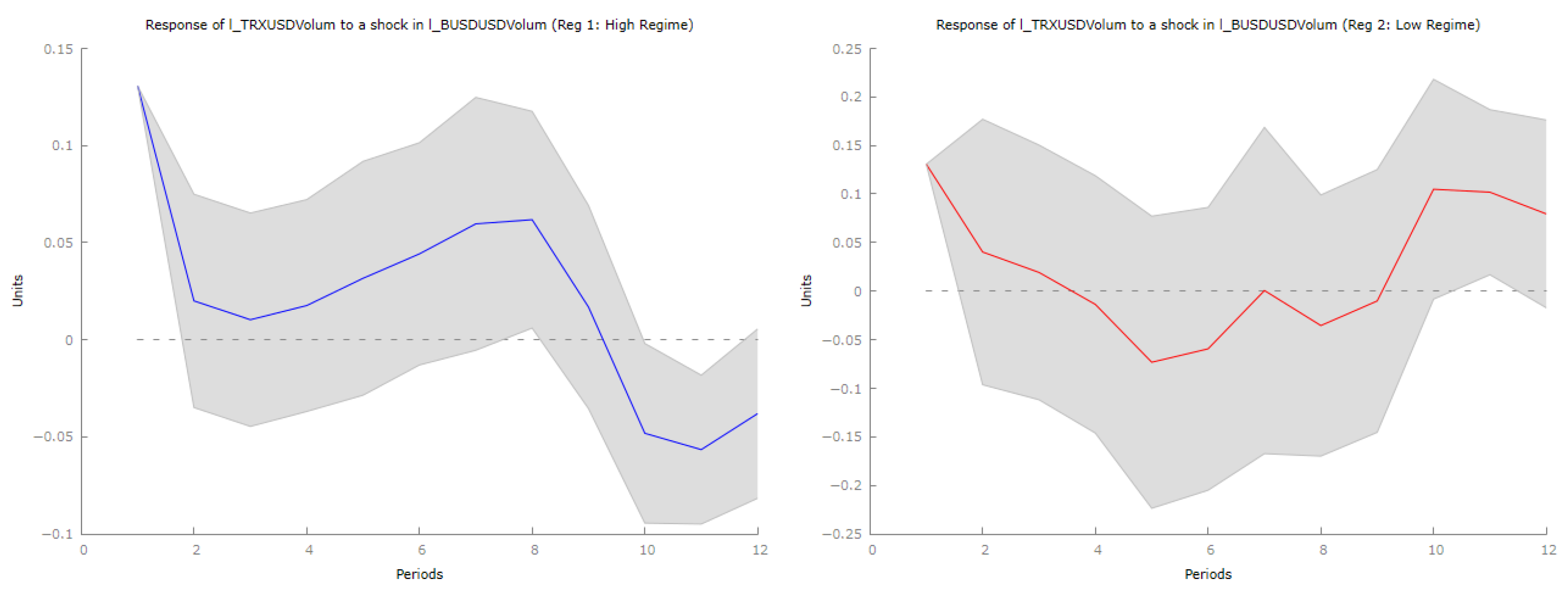

To quantify the net migration of trading activity following the BUSD delisting, we examined the impulse responses of stablecoin volumes to a BUSD-specific shock. As shown in

Figure 7, the results indicated that BUSD volume contractions are associated with economically meaningful but transitory reallocations toward USDT and USDC, whereas responses for DAI, FRAX, and TUSD remain quantitatively limited. Importantly, these reallocations are large relative to BUSD’s own baseline liquidity but small in percentage terms relative to the substantially larger trading volumes of USDT and USDC, indicating targeted substitution effects rather than broad-based increases in market-wide trading activity.

To assess whether these patterns simply reflect aggregate liquidity fluctuations, the Local Projections are estimated in a multivariate system that conditions on the joint dynamics of major stablecoins and large cryptocurrencies (BTC, ETH, TRX). This specification absorbs common market-wide volume shocks and slowly evolving liquidity conditions through the lag structure. Once these dynamics are controlled for, the BUSD-specific innovation continues to generate short-run, asset-specific reallocations toward USDT and USDC, with no evidence of persistent volume effects beyond the immediate adjustment horizon. This supports the interpretation of the documented migration as a temporary and targeted response to the BUSD delisting, rather than a manifestation of generalized market-wide volume shifts.

In

Figure 8, the impulse response function of USDT trading volume following a positive shock in BUSD volume shows a strong initial spike, indicating that traders promptly shift from BUSD to USDT as an alternative stablecoin. This suggests USDT captures significant displaced trading activity. After this initial increase, the response gradually declines, with a temporary secondary rise around the sixth period, likely reflecting delayed market adjustments. Ultimately, USDT volume declines further, indicating the transient nature of this liquidity migration.

Similarly, USDC exhibits an immediate positive response following a BUSD shock, confirming it as an alternative stablecoin. Like USDT, USDC’s initial increase diminishes over time with a similar secondary peak, suggesting rebalancing strategies among traders. However, it also transitions to negative values later, indicating that while it temporarily absorbs displaced BUSD volume, this effect is short-lived.

Overall, both USDT and USDC emerge as primary alternatives to BUSD during trading volume declines, reflecting their dominant positions in the stablecoin market. The observation of secondary peaks indicates liquidity shifts occur in waves due to trading algorithms and market frictions. Long-term declines in USDT and USDC volumes suggest that liquidity reallocation is temporary, reverting to equilibrium as market conditions stabilize.

From a regulatory standpoint, these findings illustrate the interconnected nature of stablecoins and how regulatory actions affecting one can lead to short-term liquidity migrations to others. However, such reallocations are not lasting, highlighting the importance of sustained market confidence in regulatory frameworks for long-term stability. Disruptions in BUSD trading prompt significant but short-lived liquidity reallocations toward USDT and USDC, emphasizing the need to monitor trading volume flows in assessing stablecoin resilience.

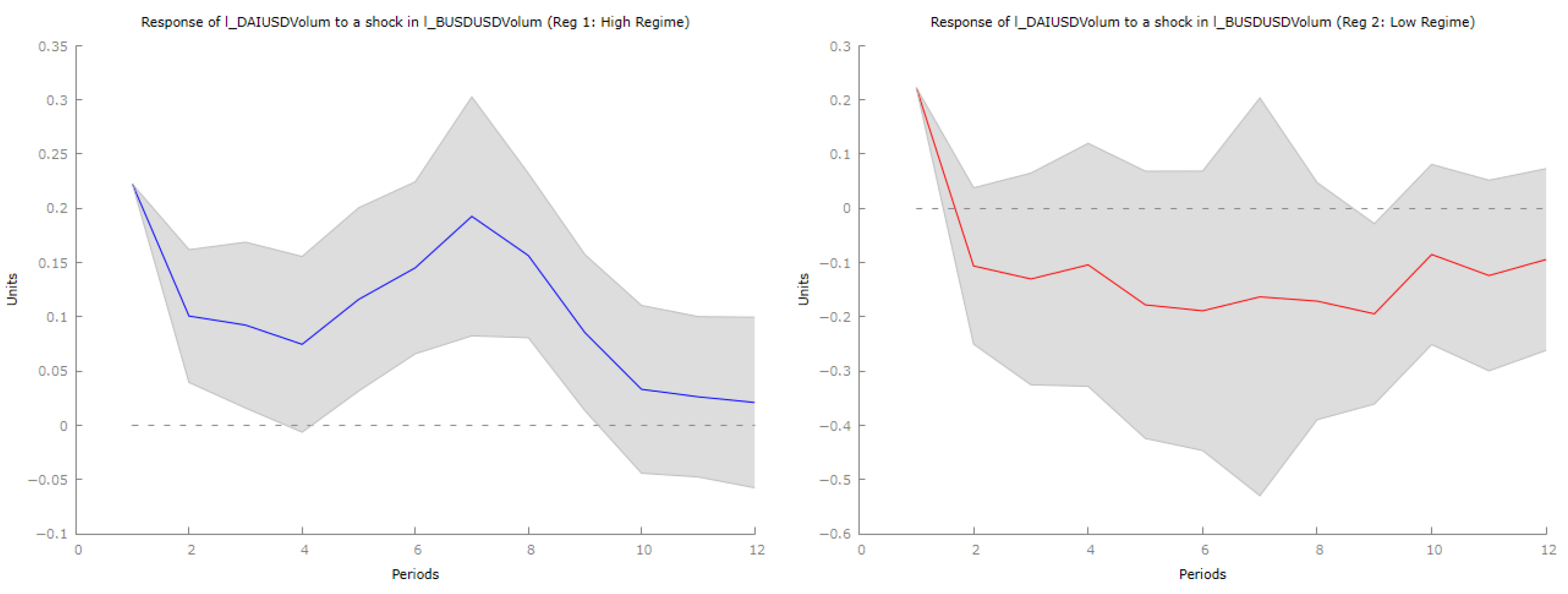

The impulse response functions (IRFs) in

Figure 9 shed light on how DAI and FRAX respond to changes in BUSD liquidity, as well as the behavior of other stablecoins. The analysis reveals that FRAX, which has a unique stabilization mechanism, shows a moderate and temporary increase in trading volume following a positive shock in BUSD trading volume. However, this response is weaker than that of USDT and USDC, indicating that FRAX is not a primary refuge for liquidity during market disruptions.

Following the initial increase, FRAX trading volume declines and eventually turns negative, suggesting that traders revert to other stablecoins rather than maintaining positions in FRAX. In contrast, DAI’s response to a BUSD shock also reflects a positive trend initially, yet its volume response is characterized by fluctuations rather than a strong shift. This variability in DAI’s trading volume may stem from its dual nature as a decentralized and partially fiat-collateralized stablecoin, leading to more irregular liquidity adjustments.

Similar to FRAX, DAI’s trading volume response becomes negative over time, indicating that liquidity reallocations are not permanent. Overall, both FRAX and DAI demonstrate weaker and more transient responses compared to USDT and USDC, highlighting that they are not primary alternatives during market stress. The results suggest that the challenges faced by algorithmic stablecoins in attracting liquidity during disruptions stem from concerns regarding stability and market adoption.

Liquidity remains concentrated among dominant stablecoins like USDT and USDC, which capture most trading volumes during disruptions. This implies that significant fluctuations predominantly affect major fiat-backed assets rather than decentralized stablecoins. The fleeting nature of liquidity shifts indicates that market confidence is more reliant on liquidity depth and regulatory clarity than on the stabilization mechanisms of individual stablecoins.

Figure 10 analyzes the dynamic response of trading volumes for TRX, TUSD, BTC, and ETH following a shock to BUSD trading volume. The impulse response functions (IRFs) reveal how different asset classes respond to changes in BUSD liquidity, shedding light on market-wide spillover effects and the roles of individual assets in managing displaced liquidity.

TRX trading volume initially surges in response to the BUSD shock, indicating liquidity reallocation towards this transactional cryptocurrency, especially within DeFi applications. However, this increase is short-lived, followed by a decline as liquidity adjustments occur in waves, potentially due to market frictions or delayed decisions.

TUSD also shows an initial increase in trading volume after the shock, suggesting temporary liquidity shifts from BUSD. Yet, the magnitude of this response is weak, indicating that TUSD is not viewed as a long-term alternative to BUSD. The transient spike may reflect speculative activity, and as the market stabilizes, liquidity reallocates to dominant stablecoins like USDT and USDC.

In contrast, BTC experiences a sustained negative response post-shock, with a decline in trading volume indicating reduced overall market liquidity, which supports the notion that stablecoin liquidity is vital for market efficiency. A similar declining pattern is observed with Ethereum, revealing its strong dependency on stablecoin liquidity, especially in DeFi contexts. This decline underscores systemic liquidity risks in the broader cryptocurrency market.

Overall, the findings highlight the varying reactions of different asset classes to changes in BUSD trading volume, reflecting complex interactions within the cryptocurrency ecosystem.

4.3. Implications for Systemic Stability: Resilience of Bitcoin and Ethereum

The response of Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum (ETH) to the BUSD delisting provides additional insights into systemic stability and shock-absorption mechanisms within cryptocurrency markets. While stablecoin disruptions generate short-term liquidity stress, the behavior of these core crypto-assets suggests a degree of resilience that contrasts with the more persistent dislocations observed for smaller cryptocurrencies and algorithmic stablecoins.

Our impulse response analysis reveals a common dual-phase adjustment pattern for both BTC and ETH. In the immediate aftermath of the BUSD delisting, trading volumes decline significantly, with short-run contractions on the order of 15–25% across specifications. This initial response reflects a temporary tightening of market-wide liquidity conditions as the disruption to BUSD trading pairs constrains settlement and arbitrage activity. Importantly, this contraction is short-lived. Within approximately two to three weeks, trading volumes gradually recover toward pre-shock levels, indicating a restoration of market functioning rather than persistent impairment.

This recovery distinguishes BTC and ETH from assets that exhibit weaker or delayed adjustment following the shock. The differential response suggests that the largest cryptocurrencies possess structural characteristics that enhance their capacity to absorb stablecoin-related liquidity disturbances. In particular, BTC and ETH benefit from deep and geographically diversified liquidity pools, multiple trading pairs (including USDT, USDC, and fiat pairs), and active cross-exchange arbitrage mechanisms. As liquidity migrates away from BUSD toward alternative stablecoins, these assets are able to rapidly re-establish effective trading infrastructure.

Fundamental considerations also play a role. The valuation of Bitcoin as a store of value and Ethereum’s position as the dominant smart-contract platform are driven primarily by network effects, technological adoption, and institutional participation rather than dependence on any single stablecoin. While stablecoins are critical for facilitating trading and liquidity provision, they do not constitute the primary source of value for these assets. This relative independence helps explain why BTC and ETH recover more quickly once alternative liquidity channels become operational.

From a systemic perspective, these findings suggest a layered structure of resilience within the cryptocurrency ecosystem. Stablecoin concentration clearly introduces vulnerabilities at the infrastructure level, as evidenced by the sharp but temporary liquidity contraction following the BUSD delisting. However, the ability of core crypto-assets to adapt through liquidity reallocation indicates that increased stablecoin concentration does not mechanically translate into immediate instability of the broader market. Instead, systemic risk appears to depend on the joint disruption of multiple layers, including the availability of credible stablecoin substitutes.

At the same time, the observed resilience should not be overstated. The initial contraction phase highlights the continued reliance of BTC and ETH on stablecoin-mediated liquidity, and the recovery documented here occurs in an environment where alternative stablecoins (USDT and USDC) remained operational and credible. More severe scenarios—such as simultaneous disruptions affecting multiple major stablecoins or coincident macro-financial stress—could lead to materially different outcomes.

Overall, the response of Bitcoin and Ethereum to the BUSD delisting complements our earlier findings on stablecoin substitution and concentration. It underscores that while stablecoin regulation has important implications for market liquidity and infrastructure, the core cryptocurrency markets exhibit meaningful, though conditional, shock-absorption capacity.

4.4. VAR Benchmark Model

We construct a VAR model utilizing log-differenced series to enhance our analysis, as local projections provide a counterpart to VAR models. The findings in

Table 2 and

Table 3 indicate the importance of maintaining a low number of lags. In pursuit of parsimony, we select

in accordance with the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).

Table 4 presents the results of the Vector Autoregression (VAR) model, which has been estimated on the log-differenced price series of the selected assets. This analysis effectively captures the short-term dynamics and interdependencies between BUSD, other stablecoins, and prominent cryptocurrencies.

Table 5 presents the results of the VAR model estimated on the log-differenced trading volumes of BUSD, other stablecoins, and major cryptocurrencies. This model captures the short-term dynamics and liquidity interactions between these assets, yielding valuable insights into how changes in trading activity propagate throughout the market.

The estimated coefficients illustrate the extent to which past volume changes in one asset influence current trading volumes in other assets. A positive and statistically significant coefficient suggests that an increase in the trading volume of one asset leads to an increase in another asset’s trading volume, whereas a negative coefficient signifies an inverse relationship. The results indicate that fluctuations in BUSD trading volume have a significant impact on the trading volumes of other stablecoins, particularly USDT and USDC, thereby confirming their role as primary substitutes during liquidity shifts. The effect on decentralized and algorithmic stablecoins, such as DAI and FRAX, appears comparatively weaker, suggesting that traders reallocate liquidity to these assets less frequently.

In the case of major cryptocurrencies like BTC and ETH, the response to changes in BUSD trading volume is more complex. The coefficients imply that reductions in stablecoin trading volume correlate with diminished liquidity in the broader cryptocurrency market, thus reinforcing the importance of stablecoins as facilitators of trading activity. The autoregressive terms indicate that liquidity shocks endure over multiple periods, signifying that changes in trading volume do not dissipate immediately but rather continue to affect market conditions over time.

These findings underscore the critical role of stablecoins in sustaining overall market liquidity and indicate that disruptions in their trading volumes may have systemic implications. The results offer significant insights for market stability, liquidity management, and regulatory oversight, particularly with regard to potential restrictions on stablecoin utilization or delistings.

6. Conclusions

The delisting of Binance USD (BUSD) highlights the central role played by stablecoins in the functioning of cryptocurrency markets. This paper provides empirical evidence on how a targeted regulatory intervention can reshape liquidity allocation, market structure, and short-run dynamics within the stablecoin ecosystem.

Prior to the delisting, BUSD accounted for approximately 15–20% of stablecoin trading volume within a moderately concentrated market. Our results show that displaced BUSD liquidity migrated overwhelmingly toward Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC), which together absorbed the vast majority of reallocated volume, leading to a marked increase in market concentration. In contrast, algorithmic and decentralized stablecoins such as DAI and FRAX captured only a marginal share of displaced liquidity, underscoring structural limitations of non-fiat-backed designs during stress episodes. Traditional cryptocurrencies—most notably Bitcoin and Ethereum—exhibited a dual-phase response characterized by short-run liquidity contractions followed by recovery, indicating adaptive capacity at the core of the crypto ecosystem, albeit alongside a clear dependence on stablecoin-mediated liquidity. Smaller tokens, such as TRON (TRX), displayed weaker adjustment patterns, consistent with lower liquidity depth and more limited market participation.

These findings matter for several reasons. First, they show that regulatory actions targeting individual stablecoins can have system-wide effects by altering market concentration and reallocating liquidity toward a smaller set of dominant intermediaries. Second, they provide empirical evidence on the limited role of algorithmic stablecoins as shock absorbers during periods of stress, informing ongoing debates on stablecoin design and resilience. Third, they indicate that while major crypto-assets display short-run resilience, this resilience is conditional and closely tied to the continued availability of credible stablecoin alternatives.

These results should be interpreted with caution. Our analysis focuses on short-run event dynamics surrounding the BUSD delisting and does not capture longer-term structural adjustments. Moreover, although the timing of liquidity shifts, the identification of structural breaks, and the asset-specific nature of the regulatory intervention support treating the BUSD delisting as a distinct shock, we acknowledge that concurrent macroeconomic and regulatory developments in 2023 may also have influenced market conditions. Our local projections framework is designed to capture conditional short-run responses, while longer-horizon and fully structural analyses are left for future research.

Overall, the BUSD delisting illustrates how regulatory interventions can generate significant reallocation effects within cryptocurrency markets, amplifying concentration in stablecoin infrastructure while leaving the stability of core crypto-assets relatively less impaired in the short run. These insights contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the interaction between regulation, market structure, and systemic risk in digital asset markets.

As potential areas for improvements,

Herbst and Johannsen (

2024) reports that Local Projections (LPs) are extensively utilized in macroeconomic research to estimate impulse response functions. However, they encounter considerable small-sample bias when applied to short, persistent time series, a prevalent issue in empirical macroeconomics. This bias arises as LP estimators at horizon

h depend on a weighted sum of the true impulse responses at horizons up to

h, resulting in attenuation bias (where estimates are biased toward zero) when the data exhibit positive autocorrelation and hump-shaped responses. Such bias is economically significant within typical sample sizes, with a median

in the reviewed studies, and persists even with the use of panel data and fixed effects. The authors propose a bias-correction method based on higher-order expansions of the estimator, which mitigates but does not completely eliminate the bias, while cautioning that autocorrelation-robust standard errors (e.g., Newey–West) may underestimate uncertainty due to finite-sample limitations. Their analysis highlights that LP estimates are not ’local’ in small samples, as the inherent bias connects responses across different horizons, thus challenging the method’s appeal as a less restrictive alternative to VARs. Notwithstanding these limitations, it is posited that the original findings concerning BUSD delisting presented in this paper deserve careful consideration.

As promising avenues for future research, the research conducted by

Inoue et al. (

2024) explores the validity of state-dependent local projection (LP) estimators for the analysis of macroeconomic shocks. The study demonstrates that these estimators can enhance classical linear local projections by integrating state-dependent nonlinearities. While traditional linear LPs operate under the assumption of time-invariant responses, state-dependent LPs condition impulse responses based on the economic state, such as differentiating between recessions and expansions. This approach provides more nuanced insights into asymmetries present in the business cycle. The authors ascertain that when the economic state is exogenous, LP estimators effectively recover population responses, regardless of the magnitude of the shock. However, under conditions of endogenous states—commonly encountered in practice—these estimators identify only marginal responses to infinitesimal shocks, rather than average responses to larger shocks that bear significance for policy formulation. Simulation results indicate considerable biases, reaching up to 82% in impulse responses and 40% in fiscal multipliers, when applying state-dependent LPs to endogenous states with non-infinitesimal shocks, thereby raising concerns regarding their reliability in standard applications. Despite these challenges, the framework indicates a promising direction for future inquiry: the development of nonparametric estimators capable of accurately recovering state-dependent average responses even for substantial shocks, particularly when economic states interact endogenously with macroeconomic dynamics. This extension has the potential to reconcile the flexibility offered by LPs with their structural validity, thereby advancing the capability of empirical macroeconomics to model nonlinear propagation mechanisms.

Lastly, the Bayesian Local Projections (BLP) framework introduced by

Ferreira et al. (

2025) enhances classical linear local projections by addressing the inherent bias-variance trade-off associated with multi-step forecasting and impulse response estimation. By integrating hierarchical informative priors that regularize LP coefficients—including specifications based on random-walk, dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE), and vector autoregression (VAR)—the BLP framework substantially mitigates the estimation uncertainty prevalent in classical LPs while preserving their flexibility within finite samples. The methodology incorporates a sandwich covariance estimator to address serially correlated residuals and employs data-driven hyperpriors that dynamically optimize prior tightness at various horizons, thereby ensuring a balance between parametric restrictions and nonparametric flexibility. Empirical applications indicate that BLP yields impulse responses characterized by richer dynamic adjustments than those produced by VARs, all while maintaining comparable estimation uncertainty. Furthermore, it surpasses both classical LP and smooth LP alternatives in terms of efficiency. This Bayesian regularization approach, particularly its capability to integrate structural model priors into projection coefficients, paves the way for future research in structural shock identification, density forecasting, and robust policy analysis amid model uncertainty. We contend that both techniques could be effectively utilized to further our understanding of the phenomenon of BUSD delisting in forthcoming research endeavors.