3.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

All experiments in this study were carried out on a consistent computer platform. The hardware specifications comprised: Windows 10 Professional operating system, an 11th-generation Intel® Core i9-11900K processor (3.50 GHz), 64 GB DDR5 RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 Ti SUPER GPU with 12 GB VRAM. The programming language used was Python 3.8.20, and the development framework employed was PyTorch 2.0.0+cu118. For more detailed configuration information, please refer to

Table 2.

The experiment accelerated the training process by configuring cuDNN v8.9.7 with CUDA 12.7. Additionally, during the training of the ink droplet morphology detection model, a series of training parameters were fine-tuned to enhance the model’s performance. All models were trained from random initialization without leveraging external pretrained weights, ensuring the learned features were specifically optimized for the domain of ink droplet imagery. The entire training process was set to run for 200 epochs, with the key training parameters comprising: processing 16 images per batch, an initial learning rate of 0.01, and employing the SGD optimizer. To enhance training efficiency and accelerate convergence, this study implemented an early stopping mechanism with a Patience value of 20. Specifically, if no performance improvement was observed over 20 consecutive checks, the training process would terminate. Ultimately, training ceased at the 179th epoch, which also corresponded to the model’s best performance. Detailed training parameters are provided in

Table 3.

To improve the model’s detection capability for inkjet droplet morphology, the mosaic data augmentation strategy was disabled during the final 10 training epochs. Furthermore, to strengthen the model’s generalization ability, various data augmentation techniques were employed, including auto-augmentation and random erasing.To ensure a comprehensive and statistically reliable evaluation, we adhere to the following protocols: (1) Model performance is evaluated using both the mean Average Precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP50) and the more stringent COCO-style mAP averaged over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05 (mAP@[0.5:0.95]). (2) Critical ablation and comparison studies were conducted over five independent training runs with different random seeds to account for variance. The reported metrics are the mean values from these runs, demonstrating stable convergence as evidenced by the learning curves.

3.2. Ablation Experiment

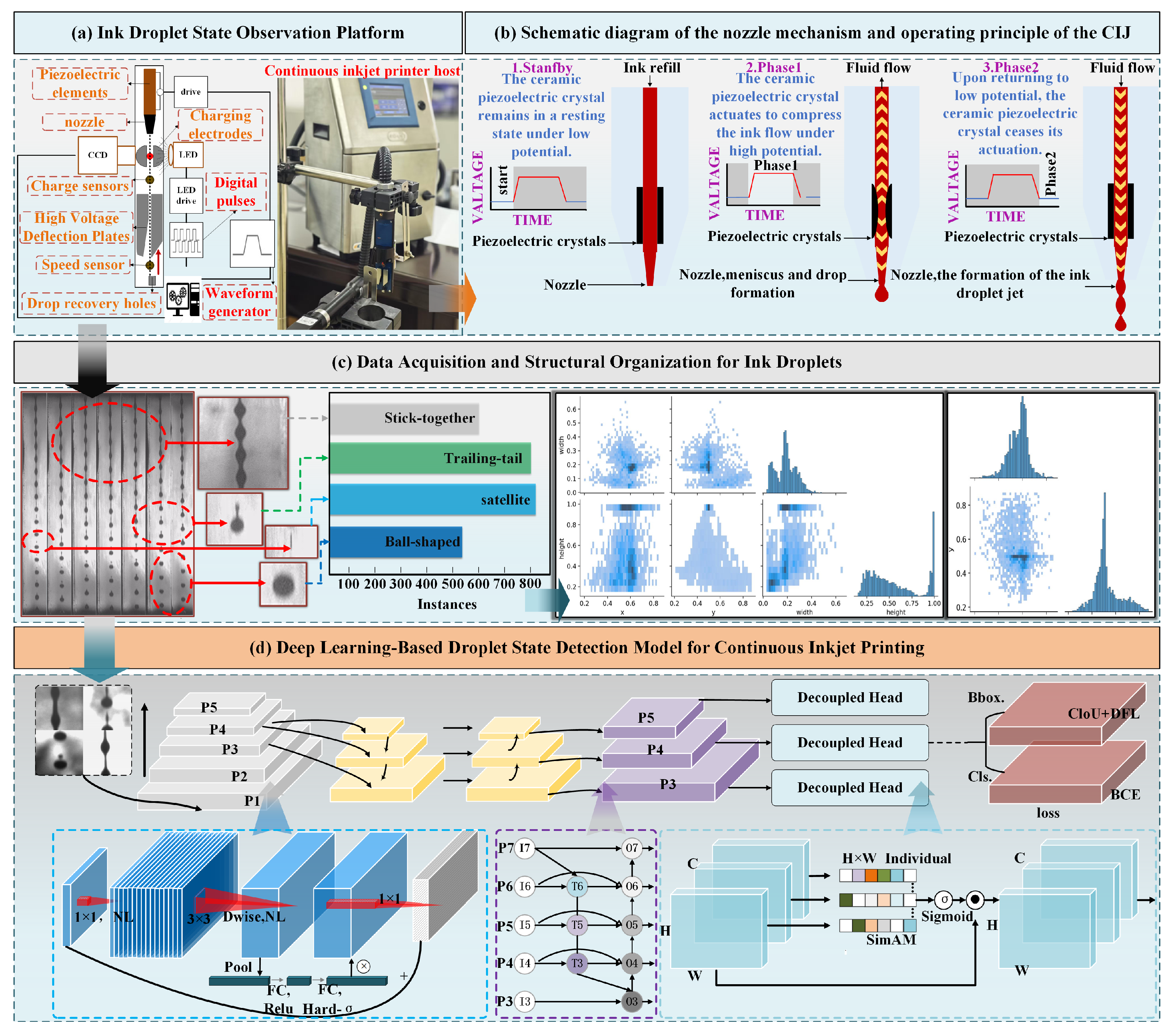

This study introduced three critical enhancements to the original YOLOv8 model: substituting the backbone network of YOLOv8 with MobileNetV3, utilizing BiFPN as the neck network, and incorporating the lightweight self-attention mechanism SimAM. A series of six ablation experiments were performed to systematically assess the individual and combined contributions of the three proposed modules (MobileNetV3, BiFPN, SimAM) to the performance of the MBSim-YOLO model for ink droplet state detection. Additionally, these experiments aimed to validate the influence of the MobileNetV3 backbone network, BiFPN, and SimAM on the overall performance of the MBSim-YOLO detection model. This study systematically investigated and validated various combinations of the enhanced modules. Each row in

Table 4 corresponds to a specific combination of the three enhancement modules, as clearly indicated by the checkmarks (✓) in the first three columns. The first row represents the YOLOv8n baseline without any of the proposed modules.

In the enhanced model, several innovative modules were incorporated, effectively minimizing the computational cost. Through the optimization of the backbone network using MobileNetV3, the model’s parameter count was reduced by 57.72%, and the GFLOPs decreased by 29.63%, accompanied by a minor reduction in accuracy. This approach substantially improved the model’s computational efficiency. By incorporating BiFPN into the neck network optimization of the YOLOv8 model, the Recall and mAP50 metrics were enhanced by 0.3 and 0.1 percentage points, respectively. By incorporating SimAM into the head network of the YOLOv8 model, the Precision and Recall metrics were enhanced by 0.6 and 0.5 percentage points, respectively.

Furthermore, the integration of the aforementioned modules leads to a further enhancement in network performance. By employing MobileNetV3 as the backbone network and introducing BiFPN, Precision is increased by 1.7 percentage points, while GFLOPs and Parameters are reduced by 66.67% and 54.94%, respectively. Building upon this foundation, the incorporation of SimAM further improves detection accuracy without substantially increasing the number of parameters or computational burden. In comparison to using only MobileNetV3 as the backbone network for YOLOv8, despite a slight increase in the number of parameters, Precision, Recall, F1 score, and mAP50 improve by 3%, 0.6%, 2%, and 0.2%, respectively. Notably, the more stringent mAP@[0.5:0.95] metric shows a more pronounced improvement of 2.4 percentage points (from 73.4% to 75.8%), indicating that the full set of enhancements (MobileNetv3 + BiFPN + SimAM) particularly benefits localization precision at higher IoU thresholds. To provide a more granular assessment of model performance, per-class mAP@[0.5:0.95] results are reported in

Table 5, Each row in

Table 5 corresponds to a specific combination of the three enhancement modules, as clearly indicated by the checkmarks () in the first three columns. The ablation analysis indicates that the SimAM attention module yields the most substantial individual gain on the challenging satellite droplet class. Furthermore, the full MBSim-YOLO configuration achieves either the best or competitive performance across all four droplet categories, demonstrating consistently balanced improvements. Notably, significant gains are observed in the two most difficult classes satellite and stick-together which are critical for robust and reliable inkjet print quality monitoring in industrial settings. Finally, through the comprehensive application of these three improvement strategies, compared with the original model, Parameters and computational burden are significantly decreased by 78.81% and 75.31%, respectively. Meanwhile, both Precision and Recall improved by 0.4 percentage points, while the F1 score and mAP50 increased by 0.1 percentage points, further validating the effectiveness of the proposed method. As illustrated in

Figure 8a, the loss curve of the training set demonstrates that the integration of MobileNetV3, BiFPN, and SimAM not only substantially decreased the loss value but also significantly boosted the detection performance.

The confusion matrix is a standard tool for evaluating multi-class classification performance. In this study, it is used to visualize the detailed classification performance of our model across the four ink droplet states. The matrix is structured such that each row corresponds to the true (ground truth) droplet category, and each column corresponds to the predicted category. Therefore, each cell at the intersection of row

i and column

j displays the count (or proportion) of droplets with true class

i that were predicted as class

j. The values along the main diagonal represent the number of correctly classified droplets for each state, with higher values indicating better per-class accuracy. Conversely, the off-diagonal elements reveal the specific types and frequencies of misclassifications, identifying which droplet states are most frequently confused with one another [

36]. It is important to note that the background label in the confusion matrix does not correspond to an annotated class. The annotation process of the experiment only draws bounding boxes for the four pre-cursor droplet states mentioned above. The backgroundrow and column are automatically generated by the evaluation toolkit to represent false positive detections (predictions that do not intersect with any ground-truth droplet) and false negatives (ground-truth droplets that were not detected), respectively. Therefore, the matrix primarily assesses the classifier’s ability to distinguish among the four droplet states, while the backgroundcells quantify localization errors against non-droplet regions.

Figure 8b presents the confusion matrix of the enhanced YOLOv8 model. By utilizing the lightweight backbone network MobileNetV3, YOLOv8 achieves a notable increase in computational efficiency at the expense of some model accuracy. Upon integrating the BiFPN and SimAM modules into this architecture, the prediction accuracy for all four ink droplet states is further improved. Compared to the original model, MBSim-YOLO not only decreases the demand for computational resources but also enhances the detection accuracy of ink droplet states more effectively.

3.3. Comparison Experiments of Different Models

To verify the superior performance of the MBSim-YOLO model for ink droplet state recognition, a comprehensive comparative experiment was conducted against several advanced models. To ensure a fair and rigorous comparison, all baseline models were constructed as full object detectors and trained under an identical protocol, as shown in

Table 3. Specifically, the models typically used as classification backbones were implemented within established detection frameworks: the ResNet entry denotes a RetinaNet detector with a ResNet-50 backbone and FPN neck; the MobileViT-xxs entry denotes an FCOS detector with a MobileViT-xxs backbone and a simple FPN neck; the EfficientNet entry denotes an EfficientDet-D0 detector with an EfficientNet-B0 backbone and BiFPN neck [

37,

38]. The ablation variants (+GhostNetv2, +ShuffleNetv2, +MobileNetv3) were constructed by replacing the backbone of our base YOLO-style detector. For clarity,

Table 6 summarizes the detailed detector configurations of the key classification-based models.

Table 7 provides a detailed comparison of the performance of each model in the ink droplet morphology detection task and presents specific comparison data. The ResNet model demonstrates exceptional performance in terms of Precision, Recall, F1 score, and mAP50, achieving values of 98.7% respectively. However, its high computational complexity, with GFLOPs at 150.8 and a parameter count of 187.4 M, indicates a significant demand for computing resources. This is primarily due to its deep network structure, which results in slower inference speeds and may become a performance bottleneck in high real-time tasks or scenarios with limited hardware resources. The EfficientNet model exhibits relatively balanced performance across various metrics. Compared to other large neural network models, it has fewer parameters (5.6 GFLOPs and 7.25 M parameters), significantly reducing storage space and computational resource requirements. However, its detection accuracy is slightly lower than that of the MBSim-YOLO model, with Precision, Recall, F1 score, and mAP50 being 4%, 1.3%, 3%, and 0.8% lower, respectively. The MobileViT-xxs model shows certain advantages in terms of computational complexity, with GFLOPs and parameter counts of 5.3 and 4.51 M, respectively, outperforming both ResNet and EfficientNet. However, its detection accuracy is relatively low, with Precision, Recall, F1 score, and mAP50 decreasing by 10.9%, 2.4%, 7%, and 4.3%, respectively, compared to MBSim-YOLO. Furthermore, MBSim-YOLO significantly outperforms MobileViT-xxs in terms of GFLOPs and parameter count, further highlighting its efficiency and lightweight characteristics. To comprehensively assess deployment feasibility, the inference efficiency of all models was evaluated on a CPU. The detailed per-stage latency (Preprocess, Inference, Postprocess) and the resulting frames-per-second (FPS) throughput are summarized in

Table 8 and

Figure 9. The proposed MBSim-YOLO achieves the fastest core inference time of 8.51 ms, which is substantially lower than that of YOLOv8n (19.51 ms) and YOLOv9c (30 ms). Compared to other efficient models, MBSim-YOLO is approximately 23% faster than EfficientNet (11.9 ms) and 35% faster than the variant using only the MobileNetV3 backbone (13.15 ms). Consequently, MBSim-YOLO attains the lowest end-to-end latency of 11.0 ms, translating to the highest throughput of 90.9 FPS. This performance far exceeds the common real-time threshold of 30 FPS, providing concrete evidence that the model’s architectural lightweighting directly enables high-speed inference suitable for embedded systems in industrial inkjet printers.

The comparison under the mAP@[0.5:0.95] metric provides further insight into the models’ localization robustness. As shown in

Table 7, MBSim-YOLO achieves the highest score of 75.8%, a 1.3 percentage point lead over the next best model, YOLOv9c (75.2%), despite having only 2.5% of its parameters. This demonstrates that our lightweight design does not compromise precise boundary regression. A finer-grained, per-class performance analysis is provided in

Figure 10. Crucially, for the most challenging Satellite droplet class, MBSim-YOLO’s mAP@[0.5:0.95] is 74%, outperforming other efficient models, highlighting its suitability for detecting small and fragmented droplets.

In this experiment, the YOLO series models demonstrated strong overall performance. Specifically, YOLOv8 achieved 97.8%, 98.7%, 98%, and 98.8% in Precision, Recall, F1 score, and mAP50, respectively. YOLOv9c reached 98.5% and 98.9% in Precision and mAP50, respectively. Additionally, YOLOv6 matched YOLOv8’s performance in Precision and F1 score, highlighting the robust capabilities of the YOLO series in object detection tasks. However, these models exhibit relatively high computational complexity. Compared to MBSim-YOLO, YOLOv6, YOLOv8, and YOLOv9c have GFLOPs values that are 9.8, 6.1, and 100.3 higher, respectively, and parameter counts that are 13.72 M, 9.04 M, and 94.07 M larger, respectively. By contrast, the MBSim-YOLO model outperformed all other models in terms of overall performance. It achieved Recall, F1 score, and mAP50 values of 99.1%, 99%, and 98.9%, respectively, with a computational cost of only 2.0 G—approximately 76.25% of the computational cost of YOLOv8. The convergence behavior of all models, tracked via both mAP50 and mAP@[0.5:0.95] over 200 epochs, is visualized in

Figure 11. The curves show that MBSim-YOLO not only converges to a higher final performance in both metrics but also exhibits stable training dynamics with minimal fluctuations, especially in the critical later stages (epochs 160–200). In conclusion, MBSim-YOLO not only maintains high detection accuracy but also achieves substantial reductions in computational overhead, making it highly suitable for practical applications.

Furthermore, to further validate the effectiveness of the MBSim-YOLO model in reducing computational resource consumption, this study replaces the original backbone network of YOLOv8 with lightweight models, including ShuffleNetV2, MobileNetV3, and GhostNetV2 [

20,

39,

40]. An objective comparison is conducted under the same experimental conditions. The experimental results are presented in

Table 7. Owing to its unique network architecture and mobile MQA mechanism, MobileNetV3 achieves a 66.41% reduction in parameters compared to GhostNetV2 and a 25.73% reduction compared to ShuffleNetV2. In terms of detection performance, MobileNetV3 demonstrates an 8.7% improvement in Precision, a 1.9% increase in Recall, and a 4.1% enhancement in mAP@50% relative to ShuffleNetV2. However, when compared to GhostNetV2, MobileNetV3 exhibits a slight decline in detection accuracy. To address this issue, the enhanced MBSim-YOLO model successfully mitigates these deficiencies by incorporating an attention mechanism and a feature fusion module. As a result, the MBSim-YOLO model achieves significant improvements in detection accuracy over GhostNetV2, particularly in Precision (+2.8%), Recall (+0.6%), and F1 score (+2%). Moreover, compared to lightweight backbone networks such as GhostNetV2 and ShuffleNetV2, MBSim-YOLO substantially reduces computational complexity and parameter count, with GFLOPs reduced by 74.68% and Parameters reduced by 60%. These findings indicate that MBSim-YOLO is better suited for deployment on embedded devices and offers higher practical application value.

Figure 12 shows the actual detection results of various comparative models during the CIJ jetting process. Among them, only the MBSim-YOLO model yields relatively satisfactory results in detecting stick-together ink droplets. The detection accuracies of the remaining comparative models are less than optimal, and some models even exhibit cases of missed detections and false alarms.

3.4. Evaluation of MBSim-YOLO Model’s Detection Performance

This study developed the MBSim-YOLO ink droplet state recognition model by integrating MobileNetV3, BiFPN, SimAM, and YOLOv8 structures. The MBSim-YOLO model was applied to conduct detection experiments on the dataset. The results demonstrated that the MBSim-YOLO model exhibited strong performance in the ink droplet state detection task. Specifically, the precision of the model’s detection results reached 98.2%, indicating its high-precision capability in identifying ink droplets. The Recall rate achieved 99.1%, which suggests that the model rarely missed detections during the recognition process, ensuring comprehensive detection coverage. Furthermore, the model’s mAP50 reached 98.9%, reflecting its high recognition accuracy. The F1 score attained 99%, highlighting the model’s balanced performance between Precision and Recall. These findings confirm that the MBSim-YOLO model possesses high accuracy and reliability in the ink droplets state detection task, making it a valuable technical solution for related applications.

The precision-confidence and recall-confidence curves in

Figure 13 provide a nuanced view of the model’s detection behavior across different confidence thresholds. In the precision-confidence curve (

Figure 13a), precision rises sharply from 20% to nearly 100% as the confidence threshold increases from 0 to about 0.2. This indicates that even at very low confidence thresholds, the model maintains a low false positive rate, a sign of strong inherent classification capability. Precision then plateaus near 100% for thresholds above 0.5, confirming the high reliability of its high-confidence predictions. In the recall-confidence curve

Figure 13b), recall remains high (above 95%) for thresholds below 0.5, demonstrating comprehensive detection coverage. The gradual decline in recall as the confidence threshold increases beyond approximately 0.5 reflects a fundamental trade-off: the model becomes more conservative, prioritizing high-certainty predictions at the cost of potentially missing some difficult or ambiguous instances (e.g., faint satellite droplets). The optimal operating point balances these two metrics. The sustained high precision across most thresholds and the maintained high recall at moderate thresholds collectively validate the robust and reliable performance of MBSim-YOLO for ink droplet state recognition.

In addition, to evaluate the performance of the MBSim-YOLO model in detecting ink droplet states under various operating conditions of the inkjet printer, images were extracted from the test set for experimental validation. Given that the ink droplets in the images are relatively small, some images were cropped and background interference was reduced appropriately to better highlight the recognition results.

Figure 14 illustrates the detection results of the MBSim-YOLO model for ink droplet states under different pressure and amplitude settings. The results indicate that the trained model is capable of accurately identifying ink droplet state categories.