Chemical and Ultrastructural Changes in the Cuticle Observed in RabA2b Overexpressing Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

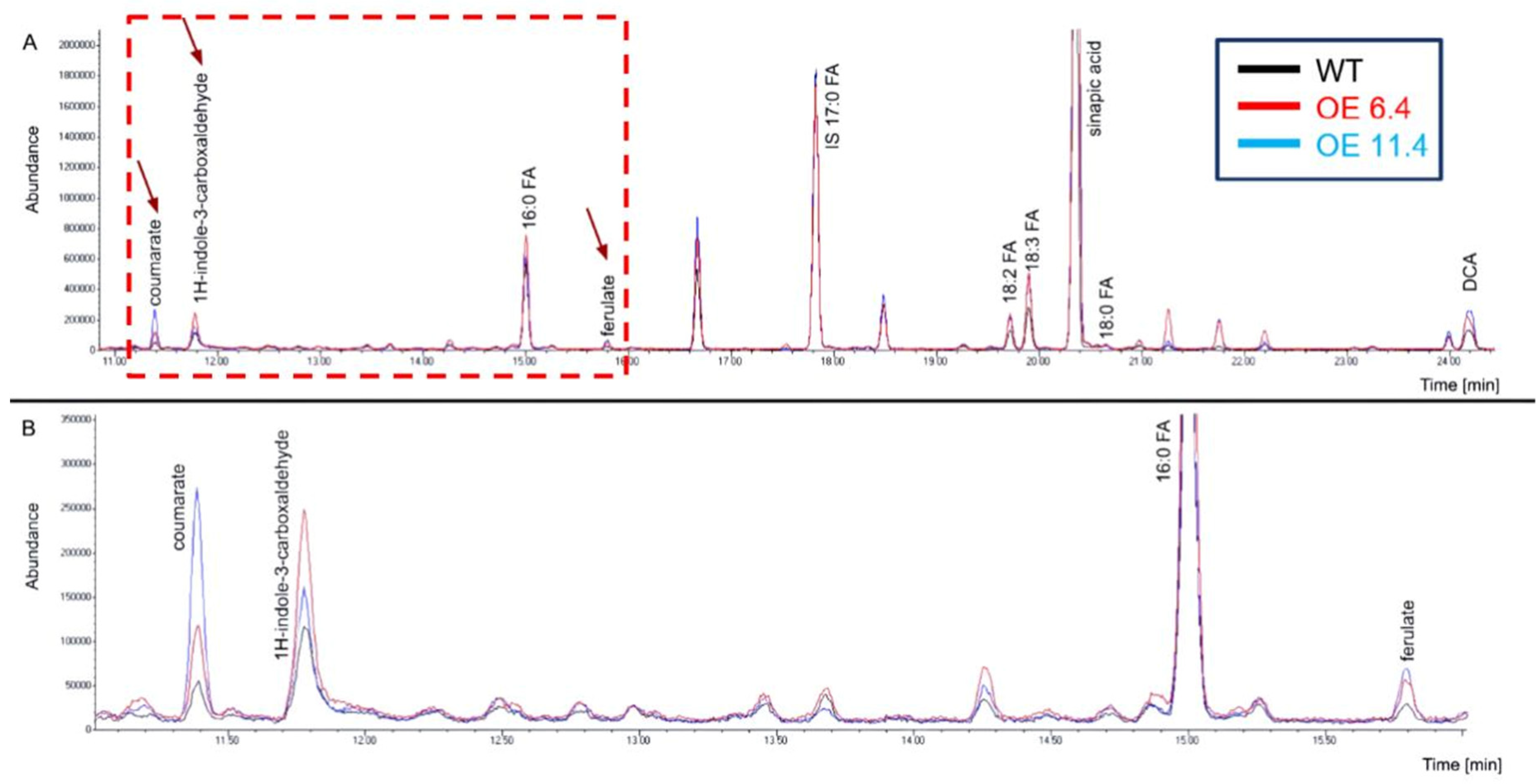

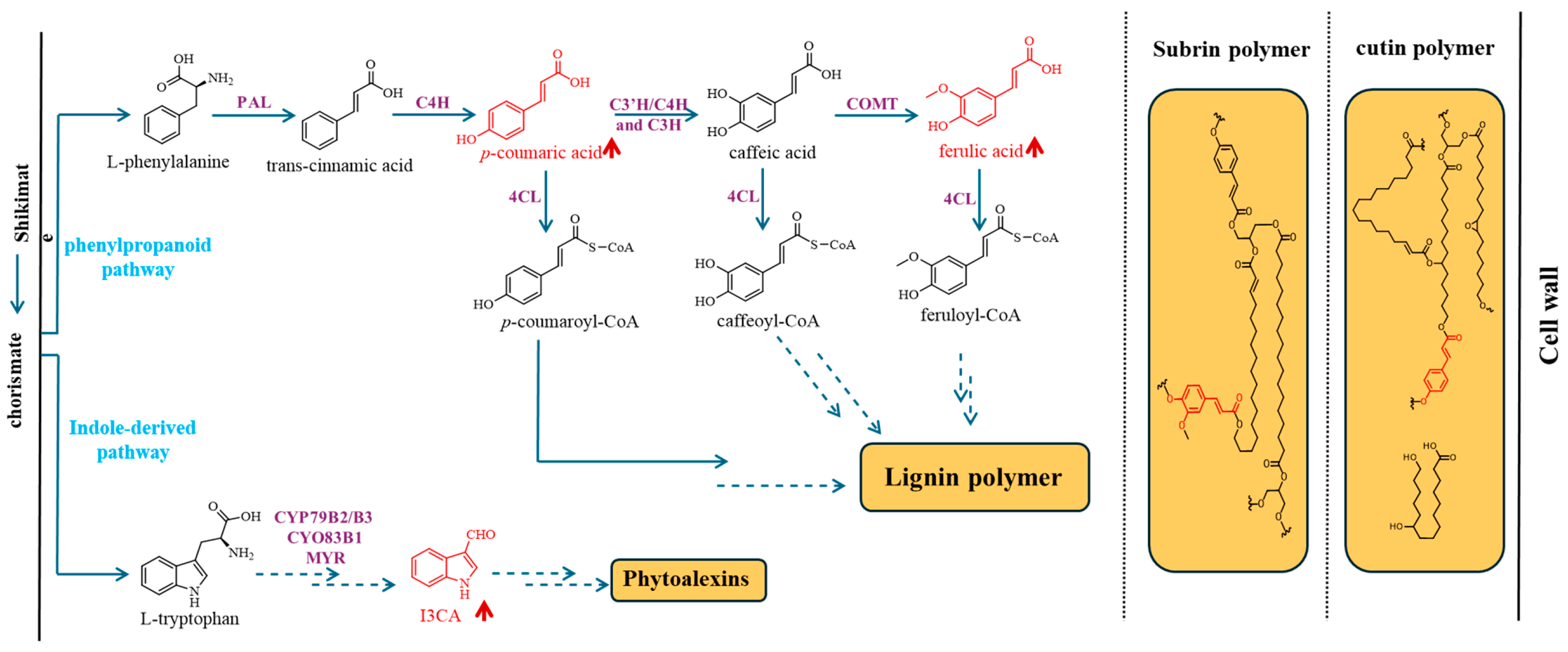

2.1. Chemical Changes in the Cuticle of RabA2b Over-Expressing Plants

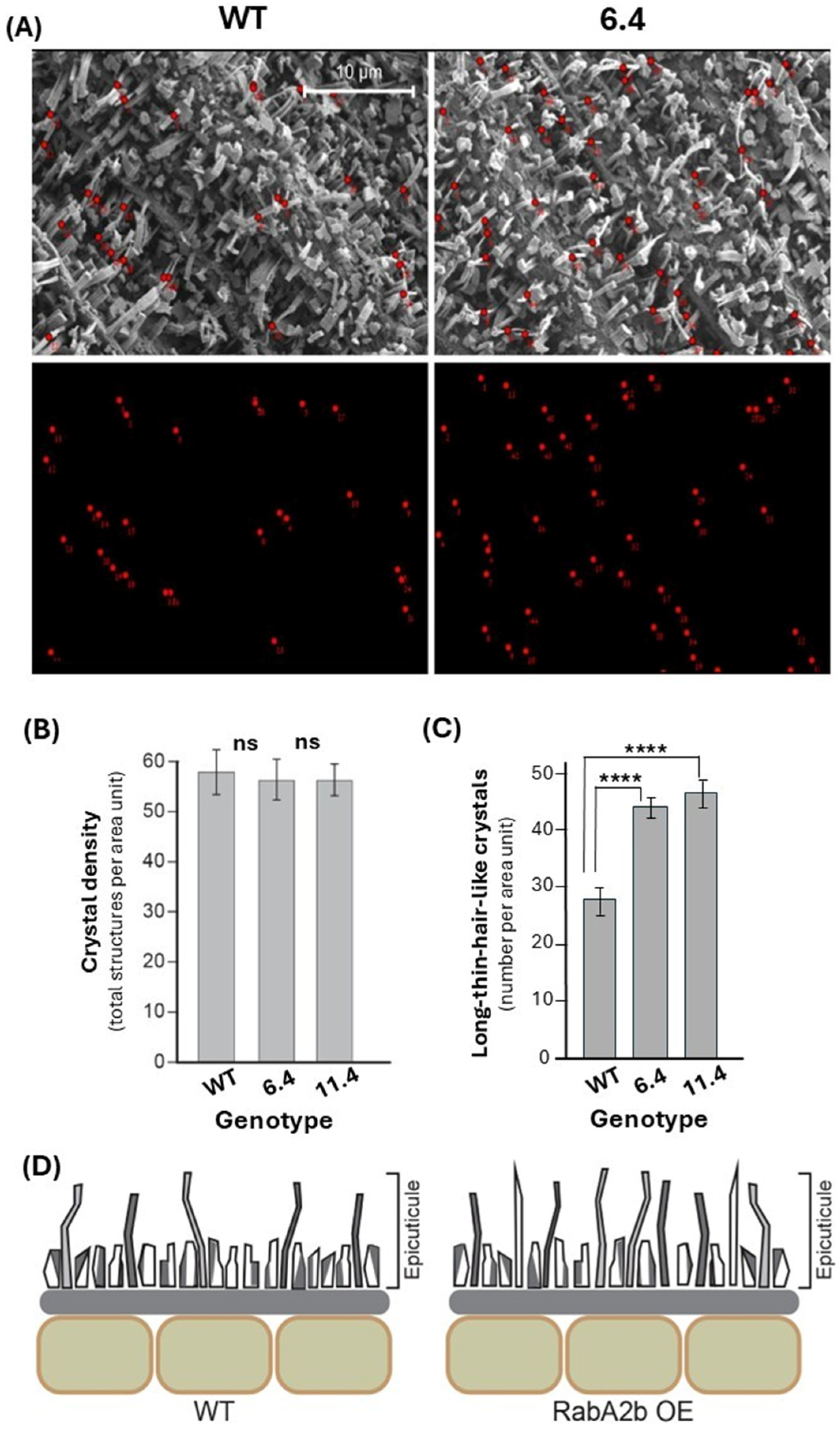

2.2. Ultrastructural Changes in the Cuticle of RabA2b Over-Expressing Plants

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

4.2. Arabidopsis Lipid Polyesters Chemical Analysis

4.3. GC-MS Analysis

4.4. SEM Imaging

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowman, J.L. Stomata: Active Portals for Flourishing on Land. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R540–R541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.W.; Harris, B.J.; Hetherington, A.J.; Hurtado-Castano, N.; Brench, R.A.; Casson, S.; Williams, T.A.; Gray, J.E.; Hetherington, A.M. The origin and evolution of stomata. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R539–R553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Valenzuela, L.; Renard, J.; Depège-Fargeix, N.; Ingram, G. The plant cuticle. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R210–R214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, G.C.; Sarkar, S.; Manasherova, E.; Aharoni, A.; Cohen, H. The Plant Cuticle: An Ancient Guardian Barrier Set Against Long-Standing Rivals. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 663165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrath, C.; Poirier, Y. Pathways for the Synthesis of Polyesters in Plants: Cutin, Suberin, and Polyhydroxyalkanoates. In Advances in Plant Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; Pergamon: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 201–239. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, R.G.; Kolattukudy, P.E. Evidence for Covalently Attached p-Coumaric Acid and Ferulic Acid in Cutins and Suberins 1. Plant Physiol. 1975, 56, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, M.; Beisson, F.; Li, Y.; Ohlrogge, J.B. Building lipid barriers: Biosynthesis of cutin and suberin. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisson, F.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Pollard, M. Solving the puzzles of cutin and suberin polymer biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkin, S.; Molina, I. Isolation and Compositional Analysis of Plant Cuticle Lipid Polyester Monomers. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 105, 53386. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Advances in the understanding of cuticular waxes in Arabidopsis thaliana and crop species. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetter, R.; Kunst, L.; Samuels, A.L. Composition of Plant Cuticular Waxes. In Annual Plant Reviews Online; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 145–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, C.N.; Jordan, G.J.; Jansen, S.; McAdam, S.A.M. A Permeable Cuticle, Not Open Stomata, Is the Primary Source of Water Loss from Expanding Leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tredenick, E.C.; Farquhar, G.D. Dynamics of moisture diffusion and adsorption in plant cuticles including the role of cellulose. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, H.E.; Watanabe, Y.; Yang, W.; Huang, Y.; Ohlrogge, J.; Samuels, A.L. Golgi- and Trans-Golgi Network-Mediated Vesicle Trafficking Is Required for Wax Secretion from Epidermal Cells. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, S.; Kamimura, N.; Tokue, Y.; Nakata, M.T.; Yamamoto, M.; Hu, S.; Masai, E.; Mitsuda, N.; Kajita, S. Identification of enzymatic genes with the potential to reduce biomass recalcitrance through lignin manipulation in Arabidopsis. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, O.; Geldner, N. The making of suberin. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, E. The Small GTPase Superfamily in Plants: A Conserved Regulatory Module with Novel Functions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycett, G. The role of Rab GTPases in cell wall metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 4061–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, D.; Gaddipati, S.R.; Tucker, G.A.; Lycett, G.W. Null Mutants of Individual RABA Genes Impact the Proportion of Different Cell Wall Components in Stem Tissue of Arabidopsis Thaliana. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambastha, V.; Matityahu, I.; Tidhar, D.; Leshem, Y. RabA2b Overexpression Alters the Plasma-Membrane Proteome and Improves Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 738694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Joubès, J. Arabidopsis cuticular waxes: Advances in synthesis, export and regulation. Prog. Lipid Res. 2013, 52, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.C.; Samuels, A.L.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L.; Pollard, M.; Ohlrogge, J.; Beisson, F. Cuticular Lipid Composition, Surface Structure, and Gene Expression in Arabidopsis Stem Epidermis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 1649–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, E.; Hanf, B.; Hagag, S.; Attias, S.; Shadkchan, Y.; Fichtman, B.; Harel, A.; Krüger, T.; Brakhage, A.A.; Kniemeyer, O.; et al. Phenotypic and Proteomic Analysis of the Aspergillus fumigatus ΔPrtT, ΔXprG and ΔXprG/ΔPrtT Protease-Deficient Mutants. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.M.; Böttcher, C.; Glawischnig, E. Dissection of the network of indolic defence compounds in Arabidopsis thaliana by multiple mutant analysis. Phytochemistry 2019, 161, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakarey, R.; Yaritz, U.; Tian, L.; Amir, R. A Myb transcription factor, PgMyb308-like, enhances the level of shikimate, aromatic amino acids, and lignins, but represses the synthesis of flavonoids and hydrolyzable tannins, in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Houari, I.; Boerjan, W.; Vanholme, B. Behind the Scenes: The Impact of Bioactive Phenylpropanoids on the Growth Phenotypes of Arabidopsis Lignin Mutants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 734070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.-L.; Deng, Y.-Q.; Dong, X.-X.; Wang, C.-F.; Yuan, F.; Han, G.-L.; Wang, B.-S. ALDH2C4 regulates cuticle thickness and reduces water loss to promote drought tolerance. Plant Sci. 2022, 323, 111405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edqvist, J.; Blomqvist, K.; Nieuwland, J.; Salminen, T.A. Plant lipid transfer proteins: Are we finally closing in on the roles of these enigmatic proteins? J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Sun, W.; Chen, Z.; Shi, L.; Hong, J.; Shi, J. Plant GDSL Esterases/Lipases: Evolutionary, Physiological and Molecular Functions in Plant Development. Plants 2022, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campoli, C.; Eskan, M.; McAllister, T.; Liu, L.; Shoesmith, J.; Prescott, A.; Ramsay, L.; Waugh, R.; McKim, S.M. A GDSL-motif Esterase/Lipase Affects Wax and Cutin Deposition and Controls Hull-Caryopsis Attachment in Barley. Plant Cell Physiol. 2024, 65, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakan, B.; Marion, D. Assembly of the Cutin Polyester: From Cells to Extracellular Cell Walls. Plants 2017, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sawy, E.R.; Abdelwahab, A.B.; Kirsch, G. Utilization of 1H-Indole-3-carboxaldehyde as a Precursor for the Synthesis of Bioactive Indole Alkaloids. Synthesis 2018, 50, 4525–4538. [Google Scholar]

- Pedras, M.S.C.; Nycholat, C.M.; Montaut, S.; Xu, Y.; Khan, A.Q. Chemical defenses of crucifers: Elicitation and metabolism of phytoalexins and indole-3-acetonitrile in brown mustard and turnip. Phytochemistry 2002, 59, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, I.; Kissen, R.; Bones, A.M. Phytoalexins in defense against pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, B.; Nawaz, G.; Zhao, N.; Liao, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Precise Editing of the OsPYL9 Gene by RNA-Guided Cas9 Nuclease Confers Enhanced Drought Tolerance and Grain Yield in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) by Regulating Circadian Rhythm and Abiotic Stress Responsive Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuepp, P.H. Tansley Review No. 59 Leaf Boundary Layers. New Phytol. 1993, 125, 477–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzer, F.C.; Andrade, J.L.; Goldstein, G.; Holbrook, N.M.; Cavelier, J.; Jackson, P. Control of transpiration from the upper canopy of a tropical forest: The role of stomatal, boundary layer and hydraulic architecture components. Plant Cell Environ. 1997, 20, 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defraeye, T.; Derome, D.; Verboven, P.; Carmeliet, J.; Nicolai, B. Cross-scale modelling of transpiration from stomata via the leaf boundary layer. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, M.A.; Sack, L.; Buckley, T.N. Leaf trichomes reduce boundary layer conductance. Authorea 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negin, B.; Hen-Avivi, S.; Almekias-Siegl, E.; Shachar, L.; Jander, G.; Aharoni, A. Tree tobacco (Nicotiana glauca) cuticular wax composition is essential for leaf retention during drought, facilitating a speedy recovery following rewatering. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 1574–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Xiao, S.; Kim, J.; Lung, S.-C.; Chen, L.; Tanner, J.A.; Suh, M.C.; Chye, M.-L. Arabidopsis membrane-associated acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP1 is involved in stem cuticle formation. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5473–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, C.; Spirandelli, D.; Franklin, E.C.; Lynham, J.; Kantar, M.B.; Miles, W.; Smith, C.Z.; Freel, K.; Moy, J.; Louis, L.V.; et al. Broad threat to humanity from cumulative climate hazards intensified by greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound Name | RT [min] | Average Fold Change 6.4 OE/WT 1 | Average Fold Change 11.4 OE/WT 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coumaric acid | 11.39 | 1.36 * | 1.59 * |

| 1H-indole-3-carboxaldehyde | 11.78 | 1.27 ** | 1.28 * |

| 16:0 FA | 15.01 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| Ferulic acid | 15.80 | 1.55 **** | 1.55 *** |

| 18:2 FA | 19.72 | 1.02 | 1.01 |

| 18:3 FA | 19.90 | 1.08 | 1.02 |

| Sinapic acid | 20.35 | 1.04 | 1.12 |

| 18:0 FA | 20.65 | 1.08 | 1.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bechar, O.; Musa, S.; Fichtman, B.; Matityahu, I.; Leshem, Y. Chemical and Ultrastructural Changes in the Cuticle Observed in RabA2b Overexpressing Plants. Plants 2026, 15, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030408

Bechar O, Musa S, Fichtman B, Matityahu I, Leshem Y. Chemical and Ultrastructural Changes in the Cuticle Observed in RabA2b Overexpressing Plants. Plants. 2026; 15(3):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030408

Chicago/Turabian StyleBechar, Opal, Sanaa Musa, Boris Fichtman, Ifat Matityahu, and Yehoram Leshem. 2026. "Chemical and Ultrastructural Changes in the Cuticle Observed in RabA2b Overexpressing Plants" Plants 15, no. 3: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030408

APA StyleBechar, O., Musa, S., Fichtman, B., Matityahu, I., & Leshem, Y. (2026). Chemical and Ultrastructural Changes in the Cuticle Observed in RabA2b Overexpressing Plants. Plants, 15(3), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030408