Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Analysis of DNA Methylation-Related Genes in Sophora Tonkinensis Under Cadmium and Drought Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Classification of C5-MTases and dMTases in S. tonkinensis

2.2. Evolutionary and Structural Features of StC5-MTases and StdMTases

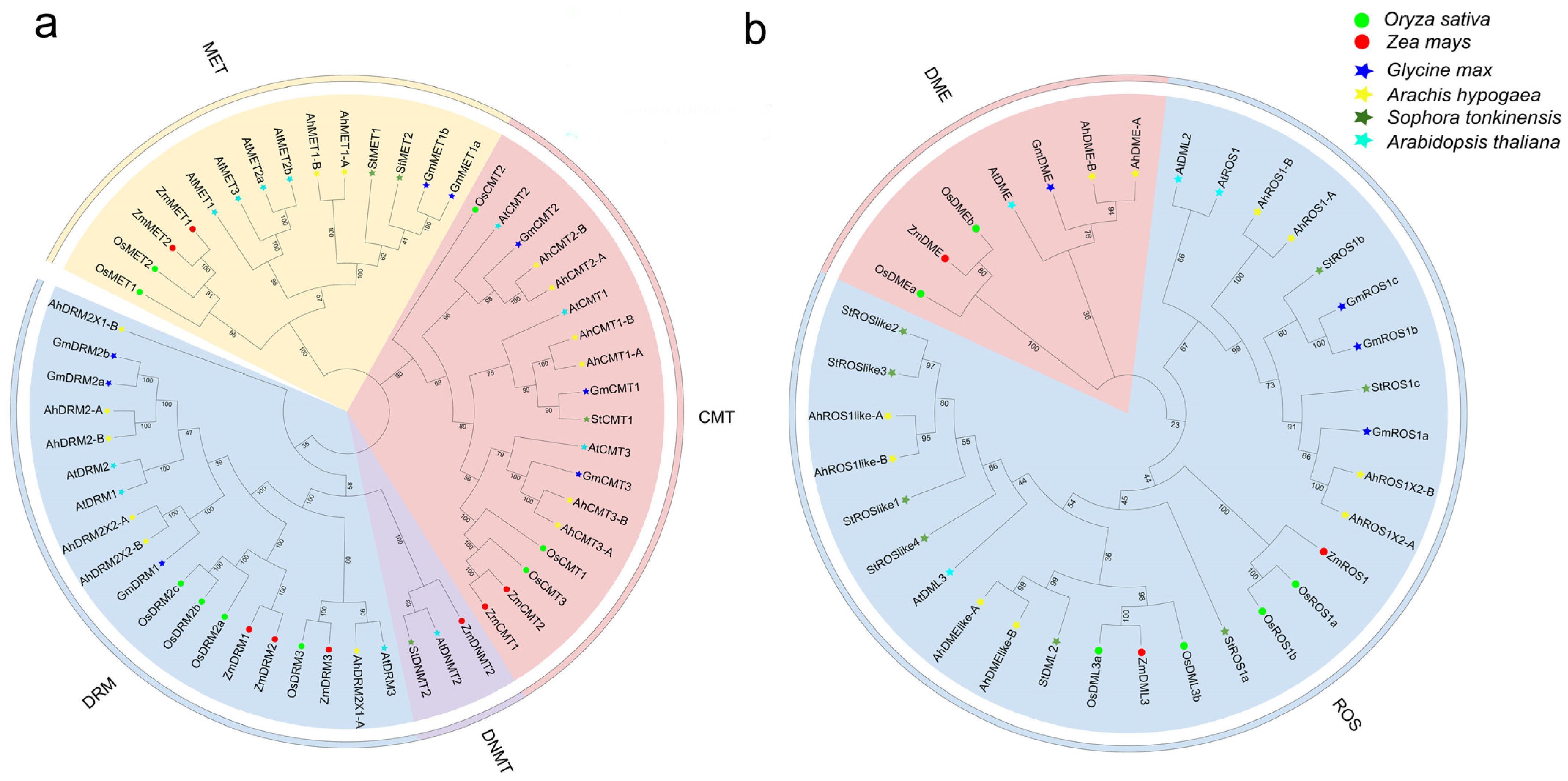

2.2.1. Phylogenetic Relationships of C5-MTases and dMTases Across Representative Plant Species

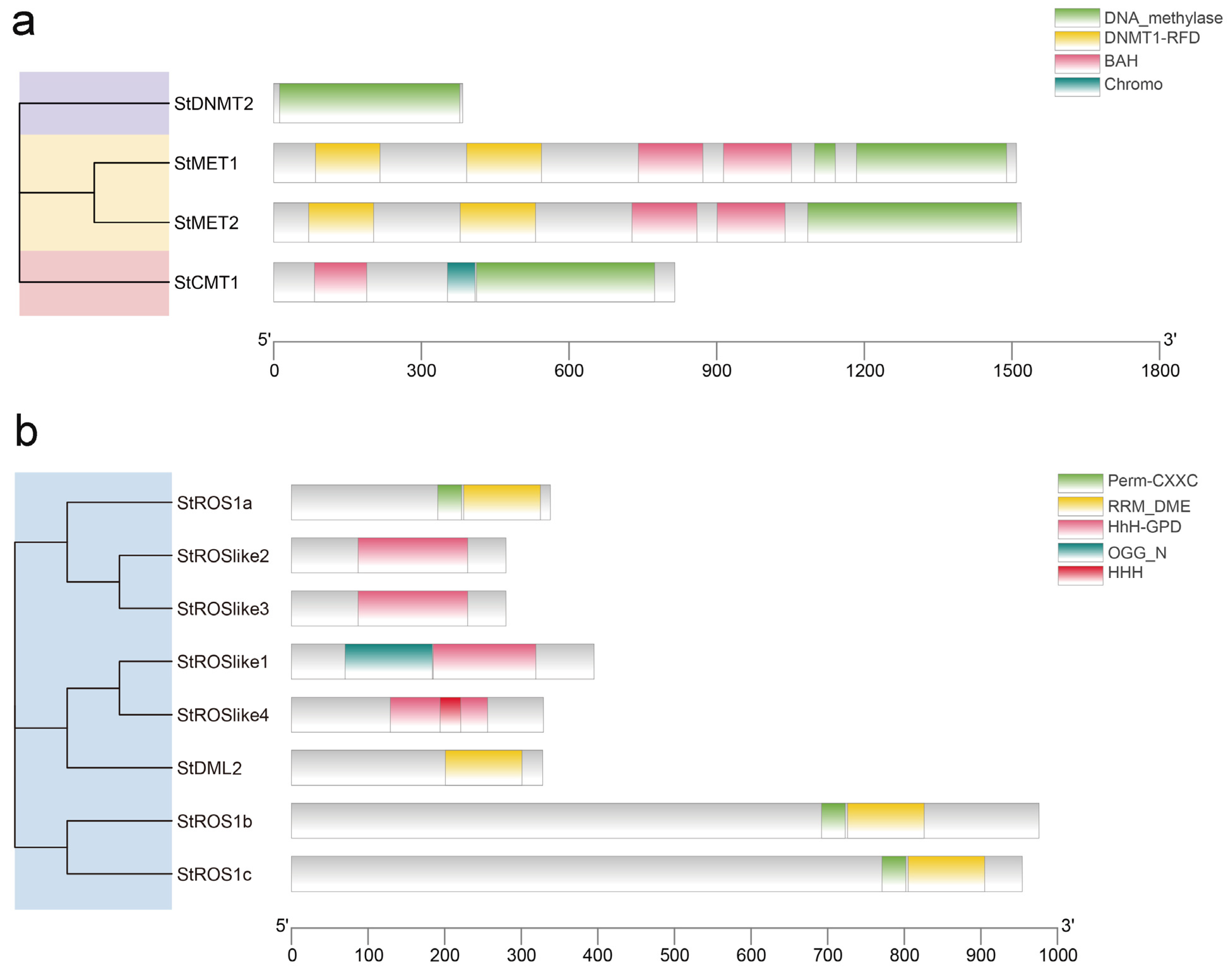

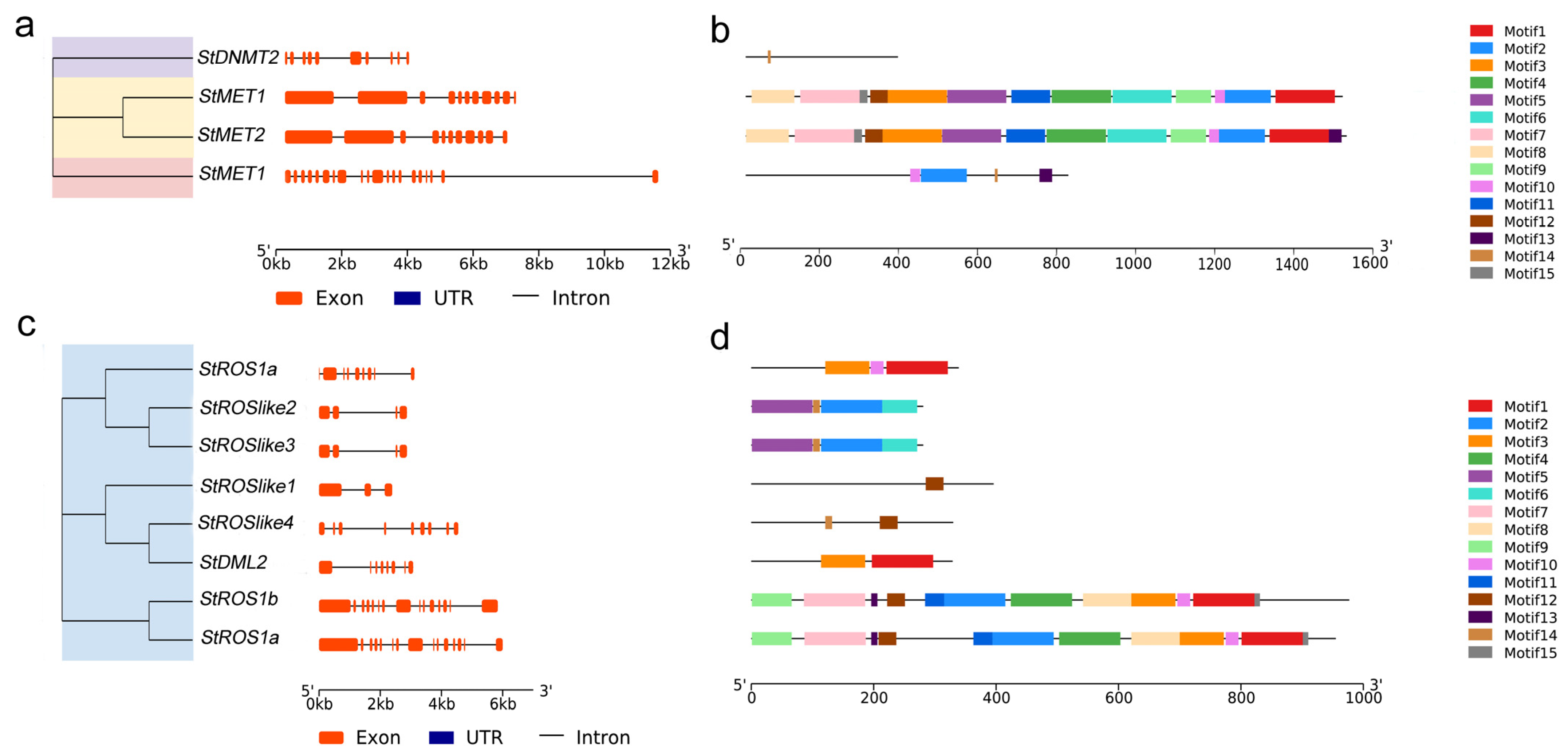

2.2.2. Conserved Domains and Motifs of StC5-MTases and StdMTases

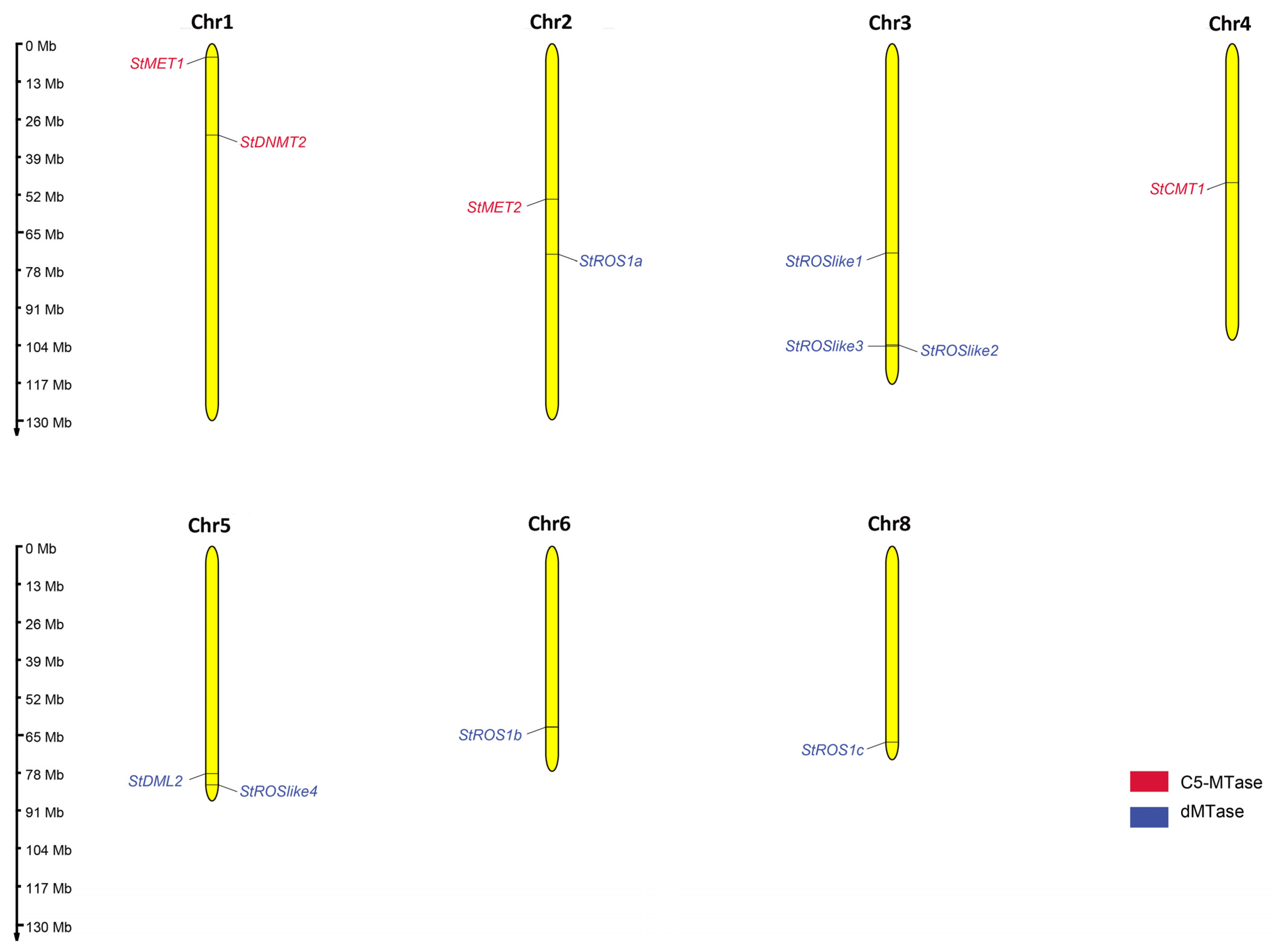

2.2.3. Chromosomal Distribution and Exon–Intron Structures of Genes Encoding StC5-MTases and StdMTases

2.2.4. Gene Duplication and Synteny Analysis of Genes Encoding StC5-MTases and StdMTases

2.3. Promoter Cis-Elements and Stress-Responsive Expression of C5-MTases and dMTases

2.3.1. Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements in the Promoter Regions of StC5-MTases and StdMTases

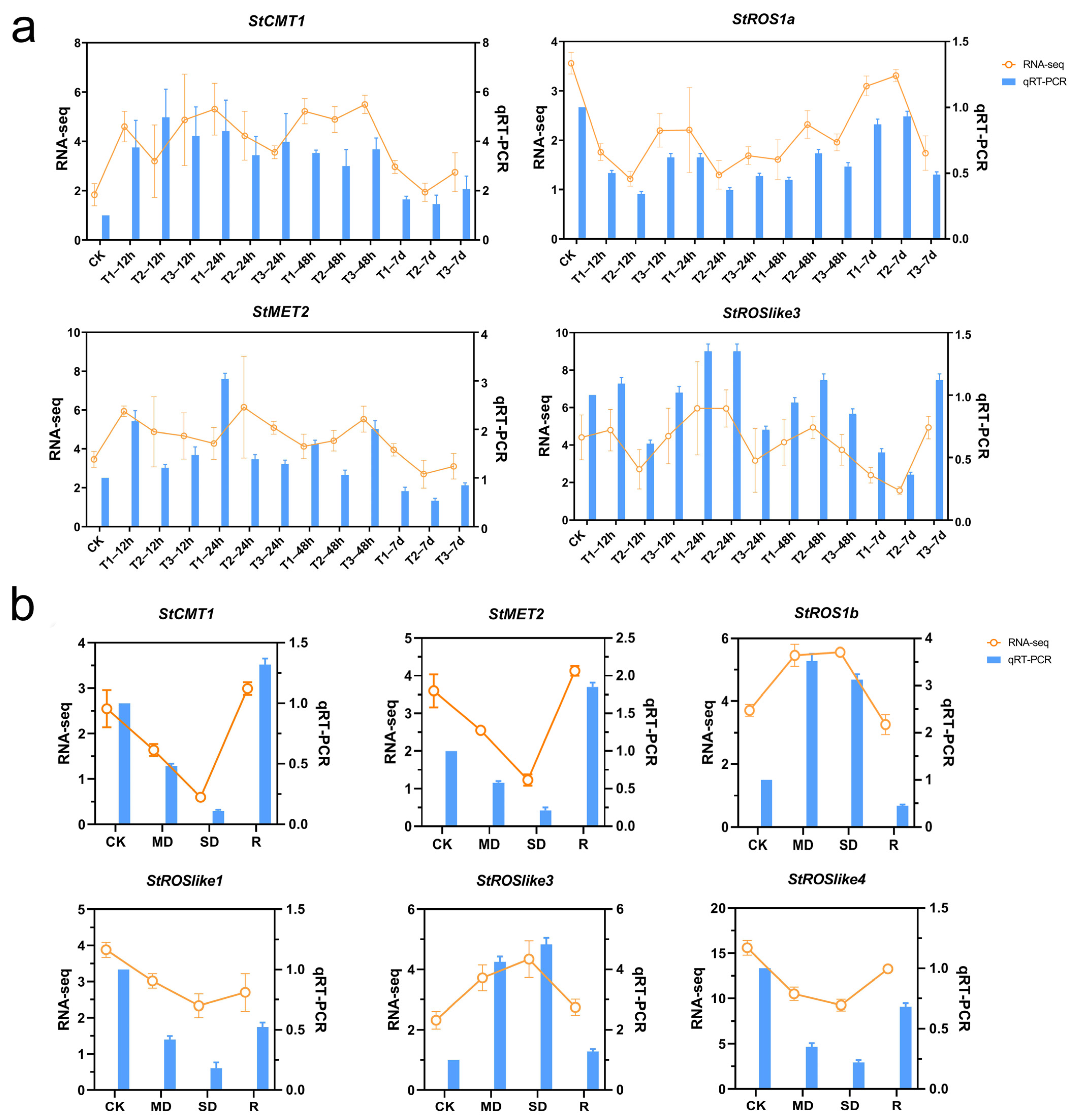

2.3.2. Expression of C5-MTases and dMTases in S. tonkinensis Under Abiotic Stress

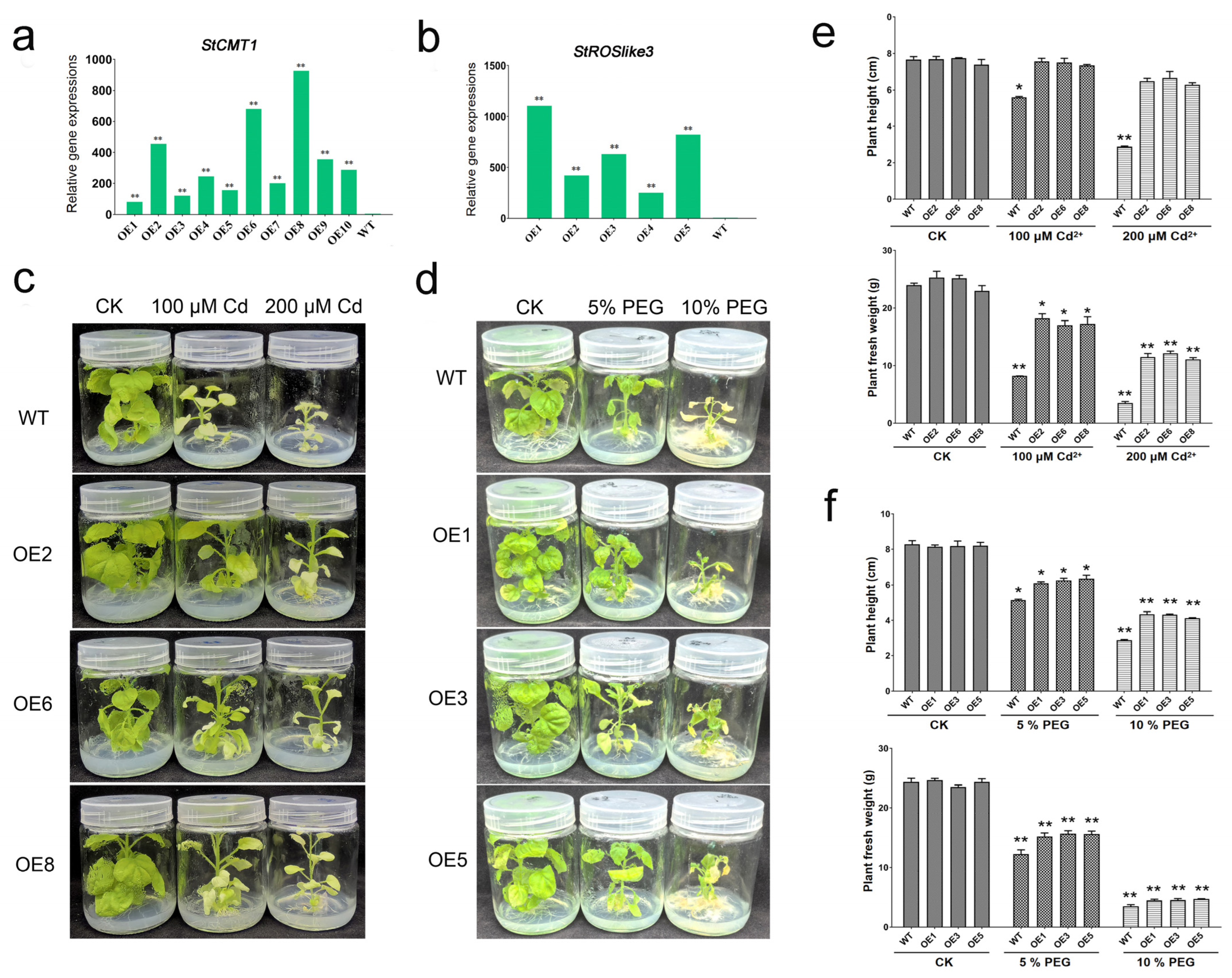

2.4. Overexpression of StCMT1 and StROSlike3 Enhances Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana

3. Discussion

3.1. Genomic and Bioinformatic Features of C5-MTase and dMTase Families in S. tonkinensis

3.2. Transcriptional Responses of StC5-MTases and StdMTases Under Cd Stress

3.3. Transcriptional Responses of StC5-MTases and StdMTases Under Drought and Rehydration

3.4. Shared Versus Stress-Specific Responses and Implications of Functional Validation

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of C5-MTase and dMTase Genes

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

4.3. Analysis of Conserved Motifs, Subcellular Localization, and Physicochemical Properties

4.4. Analysis of Gene Structure and Chromosomal Location

4.5. Collinearity and Synteny Analysis

4.6. Cis-Acting Element Analysis

4.7. Prediction of Protein Interaction Networks

4.8. Expression Analysis of C5-MTase and dMTase Genes Under Cd and Drought Stress

4.9. qRT-PCR Validation of Gene Expression

4.10. Heterologous Overexpression and Stress Phenotyping in N. benthamiana

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.; Yazaki, J.; Sundaresan, A.; Cokus, S.; Chan, S.W.L.; Chen, H.; Henderson, I.R.; Shinn, P.; Pellegrini, M.; Jacobsen, S.E.; et al. Genome-wide high-resolution mapping and functional analysis of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell 2006, 126, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Cao, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Lu, H.; Tang, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, Y. Methyl-Sensitive Amplification Polymorphism (MSAP) Analysis Provides Insights into the DNA Methylation Underlying Heterosis in Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) Drought Tolerance. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 13665–13680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, J.T.; Yung, R.L.; Richardson, B.C. DNA methylation and the regulation of gene transcription. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Tang, M.; Luo, D.; Wang, C.; Lu, H.; Cao, S.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, Y. Integrated Methylome and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal the Molecular Mechanism by Which DNA Methylation Regulates Kenaf Flowering. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 709030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Lu, H.; Wang, C.; Tang, M.; Li, Z.; Cao, S.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, Y. Physiological and DNA methylation analysis provides epigenetic insights into kenaf cadmium tolerance heterosis. Plant Sci. 2023, 331, 111663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Li, R.; Chen, P.; Luo, D.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Z. Exogenous glutathione can alleviate chromium toxicity in kenaf by activating antioxidant system and regulating DNA methylation. Chemosphere 2023, 337, 139305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, E.; Talarico, E.; Guarasci, F.; Camoli, M.; Palermo, A.M.; Zambelli, A.; Chiappetta, A.; Araniti, F.; Bruno, L. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Plant Adaptation to Cadmium and Heavy Metal Stress. Epigenomes 2025, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, C. Advances in epigenetic studies of plant cadmium stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1489155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Lin, Y. Integrated transcriptome and methylome analyses reveal the molecular regulation of drought stress in wild strawberry (Fragaria nilgerrensis). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Song, Y.; Diao, S.; He, C.; Zhang, J. Transcriptome and DNA methylome provide insights into the molecular regulation of drought stress in sea buckthorn. Genomics 2022, 114, 110345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, E.J.; Kovac, K.A. Plant DNA methyltransferases. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 43, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Jacobsen, S.E. Role of the Arabidopsis DRM methyltransferases in de novo DNA methylation and gene silencing. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Kapoor, A.; Sridhar, V.V.; Agius, F.; Abbasi, F.; Zhu, J.K. The DNA glycosylase/lyase ROS1 functions in pruning DNA methylation patterns in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Galisteo, A.P.; Morales-Ruiz, T.; Ariza, R.R.; Edwards, C.; Roldán-Arjona, T.; Ruiz-Albert, J. Arabidopsis DEMETER-LIKE proteins DML2 and DML3 are required for appropriate distribution of DNA methylation marks. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 67, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogneva, Z.V.; Dubrovina, A.S.; Kiselev, K.V. Age-associated alterations in DNA methylation and expression of methyltransferase and demethylase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biol. Plant. 2016, 60, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gao, C.; Bian, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, C.; Xia, H.; Hou, L.; Li, C.; Wang, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Comparative Analysis of Cytosine-5 DNA Methyltransferase and Demethylase Families in Wild and Cultivated Peanut. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglia, A.; Gianoglio, S.; Acquadro, A.; Valentino, D.; Milani, A.M.; Lanteri, S.; Comino, C. Identification of DNA methyltransferases and demethylases in Solanum melongena L., and their transcription dynamics during fruit development and after salt and drought stresses. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Kumari, R.; Tiwari, S.; Jain, M. Genomic survey, gene expression analysis and structural modeling suggest diverse roles of DNA methyltransferases in legumes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, H.; Lin, J.; Sun, X. Genome-wide investigation and transcriptional analysis of cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferase and DNA demethylase gene families in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) under abiotic stress and withering processing. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Zhao, H.; Luo, S.; Zheng, X.; Nie, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Z. Genome-Wide Identification of DNA Methylases and Demethylases in Kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 514993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Zeng, J.; Hou, B.; Si, J. Genome-wide identification and analysis of DNA methyltransferase and demethylase gene families in Dendrobium officinale reveal their potential functions in polysaccharide accumulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.; Raturi, V.; Gahlaut, V.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, M.; Tyagi, A.; Tiwari, J.K. The interplay of DNA methyltransferases and demethylases with tuberization genes in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes under high temperature. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 933740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yang, H.; Wan, X.; Fan, X.; Shang, X.; Fu, G. Genome-wide identification and comparative analysis of DNA methyltransferase and demethylase gene families in two ploidy Cyclocarya paliurus and their potential function in heterodichogamy. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancikova, V.; Kacirova, J.; Hricova, A. Identification and gene expression analysis of cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferase and demethylase genes in Amaranthus cruentus L. under heavy metal stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1092067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramasuriya, A.M.; Sanahari, W.M.A.; Weeraman, J.W.J.K.; Sudarshana, P.; Premakumara, G.S. DNA-(cytosine-C5) methyltransferases and demethylases in Theobroma cacao: Insights into genomic features, phylogenetic relationships, and protein-protein interactions. Tree Genet. Genomes 2024, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Tang, D.; Wei, K.; Qin, S.; Liang, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, L. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the medicinal plant Sophora tonkinensis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Burca, G.; Yong, J.W.H.; Johansson, E.; Kuktaite, R. New Insights into the Bio-Chemical Changes in Wheat Induced by Cd and Drought: What Can We Learn on Cd Stress Using Neutron Imaging? Plants 2024, 13, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Yang, H.; Pian, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, A.-M. The Uptake, Transfer, and Detoxification of Cadmium in Plants and Its Exogenous Effects. Cells 2024, 13, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Lin, Y.; Hu, S.; Zheng, S. Biochar and organic fertilizer drive the bacterial community to improve the productivity and quality of Sophora tonkinensis in cadmium-contaminated soil. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1334338. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F.; Chen, H.; Wei, G.; Qin, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X. Physiological and metabolic responses of Sophora tonkinensis to cadmium stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 1889–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wei, K.; Wei, F.; Huang, S.; Qin, S. Integrated transcriptome and small RNA sequencing analyses reveal a drought stress response network in Sophora tonkinensis. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wei, F.; Qin, S.; Wei, G.; Zhan, R. Sophora tonkinensis: Response and adaptation of physiological characteristics, functional traits, and secondary metabolites to drought stress. Plant Biol. 2023, 25, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Di, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, P.; Wang, X.; Lu, P. Systematic Analysis of DNA Demethylase Gene Families in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) and Their Expression Variations after Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yang, Z.; Liu, L.; Xie, H. DNA Methylation in Plant Responses and Adaption to Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.J.; Liu, X.S.; Tao, H.; Tan, S.K.; Chu, S.S.; Oono, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chu, Z. Variation of DNA methylation patterns associated with gene expression in rice (Oryza sativa) exposed to cadmium. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 2629–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Gao, J.; Qin, C.; Ge, M.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Shen, Y. The dynamics of DNA methylation in maize roots under Pb stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 23537–23554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Li, J.; Tran, L.S.P.; Qin, F. A transposable element in a NAC gene is associated with drought tolerance in maize seedlings. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, C.; Jiang, L.; Cao, F.; Wang, C.; Cao, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Cui, B.; Zuo, J.; et al. Methylation of a MITE insertion in the MdRFNR1-1 promoter is positively associated with its allelic expression in apple in response to drought stress. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3983–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, D.; Aliki, K.; Venetia, K.; Filippos, A.; Athanasios, T. Spatial and temporal expression of cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferase and DNA demethylase gene families of the Ricinus communis during seed development and drought stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 84, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitelli, V.; Giamborino, A.; Bertolini, A.; Saba, A.; Andreucci, A. Cadmium Stress Signaling Pathways in Plants: Molecular Responses and Mechanisms. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 6052–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, S.; Hasnain, Z.; Aslam, N.; Mumtaz, S.; Jaafar, H.Z.E. Significance of ABA Biosynthesis in Plant Adaptation to Drought Stress. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 67, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Abscisic acid in plants under abiotic stress: Crosstalk with major phytohormones. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, M. DNA Methylation Dynamics in Response to Drought Stress in Crops. Plants 2024, 13, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, M. A review of the advances and perspectives in sequencing technologies for analysing plant epigenetic responses to abiotic stress. Plant Stress 2025, 19, 101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Sun, L.; An, J.; Zhu, J.; Yan, T.; Wang, T.; Shu, X.; Wang, Z. Ectopic Expression of a Poplar Gene PtrMYB119 Confers Enhanced Tolerance to Drought Stress in Transgenic Nicotiana tabacum. Plants 2025, 14, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Huang, C.; Jin, H.; Zhao, C.; Liu, N.; Hu, S.; Xie, J. NtRAV4 Negatively Regulates Drought Tolerance by Activating NtNCED1 in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 747–760. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Ma, T.; Song, K.; Ji, X.; Xiang, L.; Chen, N.; Zu, R.; Xu, W.; Zhu, S.; Liu, W. Overexpression of NtGPX8a Improved Cadmium Accumulation and Tolerance in Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Genes 2024, 15, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, N.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S. Overexpression of NtGCN2 Improves Drought Tolerance in Tobacco by Regulating Proline Accumulation, ROS Scavenging Ability, and Stomatal Closure. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 198, 107665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, T.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Que, Y.; Guo, J.; Xu, L.; Su, Y. Sugarcane ScDREB2B-1 Confers Drought Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana by Regulating the ABA Signal, ROS Level and Stress-Related Gene Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Jeffryes, M.; Bateman, A.; Finn, R.D. The HMMER Web Server for Protein Sequence Similarity Search. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2017, 60, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Mistry, J.; Tate, J.; Coggill, P.; Heger, A.; Pollington, J.E.; Gavin, O.L.; Gunasekaran, P.; Ceric, G.; Forslund, K.; et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, D211–D222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Bateman, A.; Clements, J.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Heger, A.; Hetherington, K.; Holm, L.; Mistry, J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Aluko, O.O.; Wu, X.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G.; Cao, P. MG2C: A user-friendly online tool for drawing genetic maps. Mol. Hortic. 2021, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Paterson, A.H. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.Q.; Wang, J.; Wong, G.K.S.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator: Calculating Ka and Ks Through Model Selection and Model Averaging. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2006, 4, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Qin, S.; Wei, G.; Wei, F.; Zhan, R. Comprehensive analysis of the NAC transcription factor gene family in Sophora tonkinensis Gagnep. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Hao, Q.; Chen, P.; Ding, G.; Feng, S.; Li, J. Cloning of PmMYB6 in Pinus massoniana and an Analysis of Its Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Gene ID | CDS Length (bp) | Protein | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon Number | Intron Number | Number of aa | MW (kDa) | pI | II | AI | GRAVY | |||

| C5-MTases | ||||||||||

| CMT1 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_4.2836 | 2448 | 20 | 19 | 815 | 92.04 | 5.47 | 39.4 | 76.98 | 0.052 |

| MET1 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_1.250 | 4530 | 28 | 27 | 1509 | 170.90 | 5.78 | 46.22 | 76.13 | 0.503 |

| MET2 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_2.4148 | 4560 | 11 | 10 | 1519 | 170.94 | 5.74 | 41.85 | 75.37 | 0.502 |

| DNMT2 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_1.2492 | 1155 | 10 | 9 | 384 | 43.73 | 6.23 | 50.11 | 78.75 | 0.366 |

| dMTases | ||||||||||

| DML2 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_5.2915 | 987 | 8 | 7 | 328 | 37.02 | 4.70 | 51.16 | 71.04 | 0.577 |

| ROS1a | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_2.4917 | 1017 | 9 | 8 | 338 | 38.59 | 5.23 | 49.26 | 73.58 | 0.667 |

| ROS1b | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_6.1625 | 2931 | 15 | 14 | 976 | 109.33 | 5.63 | 48.98 | 70.45 | 0.735 |

| ROS1c | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_8.2263 | 2865 | 15 | 14 | 954 | 107.45 | 5.48 | 49.47 | 76.29 | 0.584 |

| ROSlike1 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_3.2420 | 1188 | 3 | 2 | 395 | 43.37 | 9.66 | 45.84 | 86.96 | 0.258 |

| ROSlike2 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_3.5115 | 843 | 4 | 3 | 280 | 31.67 | 9.15 | 37.78 | 83.57 | 0.620 |

| ROSlike3 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_3.5174 | 876 | 4 | 3 | 291 | 33.62 | 9.24 | 39.39 | 83.57 | 0.595 |

| ROSlike4 | evm.TU.HiC_scaffold_5.3220 | 990 | 9 | 8 | 329 | 36.61 | 9.32 | 44.8 | 88.6 | 0.301 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, F.; Qin, S.; Li, L.; Qiao, Z.; Tang, D.; Wei, G.; Lin, Y.; Liang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Analysis of DNA Methylation-Related Genes in Sophora Tonkinensis Under Cadmium and Drought Stress. Plants 2026, 15, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030396

Wei F, Qin S, Li L, Qiao Z, Tang D, Wei G, Lin Y, Liang Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Analysis of DNA Methylation-Related Genes in Sophora Tonkinensis Under Cadmium and Drought Stress. Plants. 2026; 15(3):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030396

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Fan, Shuangshuang Qin, Linxuan Li, Zhu Qiao, Danfeng Tang, Guili Wei, Yang Lin, and Ying Liang. 2026. "Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Analysis of DNA Methylation-Related Genes in Sophora Tonkinensis Under Cadmium and Drought Stress" Plants 15, no. 3: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030396

APA StyleWei, F., Qin, S., Li, L., Qiao, Z., Tang, D., Wei, G., Lin, Y., & Liang, Y. (2026). Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Analysis of DNA Methylation-Related Genes in Sophora Tonkinensis Under Cadmium and Drought Stress. Plants, 15(3), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030396