Optimal Nitrogen Application Strategies for Alfalfa Under Different Precipitation Patterns: Balancing Yield, Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency, and Soil Nitrogen Residue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Verification of the Applicability of the APSIM–Lucerne Model

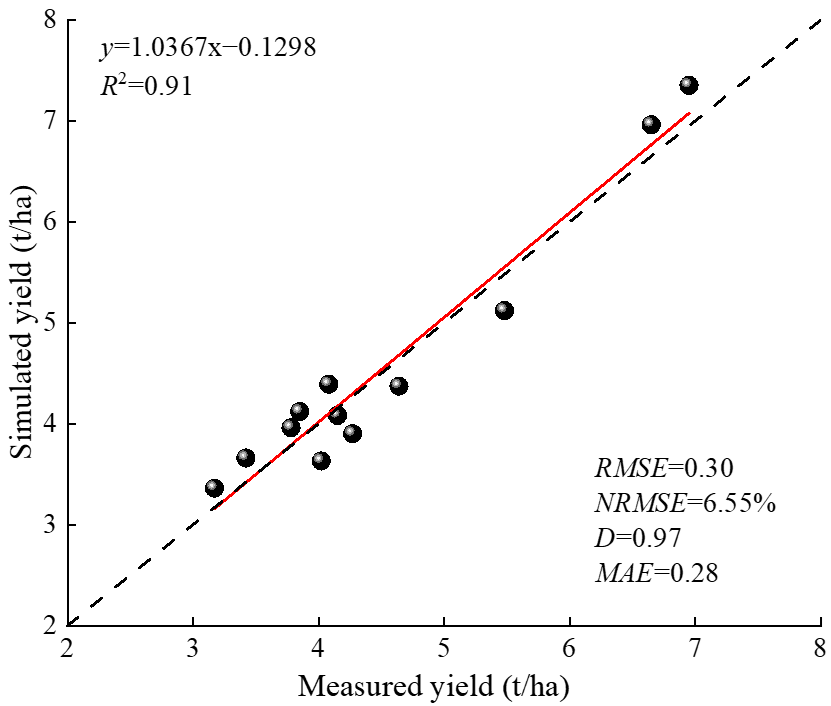

2.1.1. Yield Verification

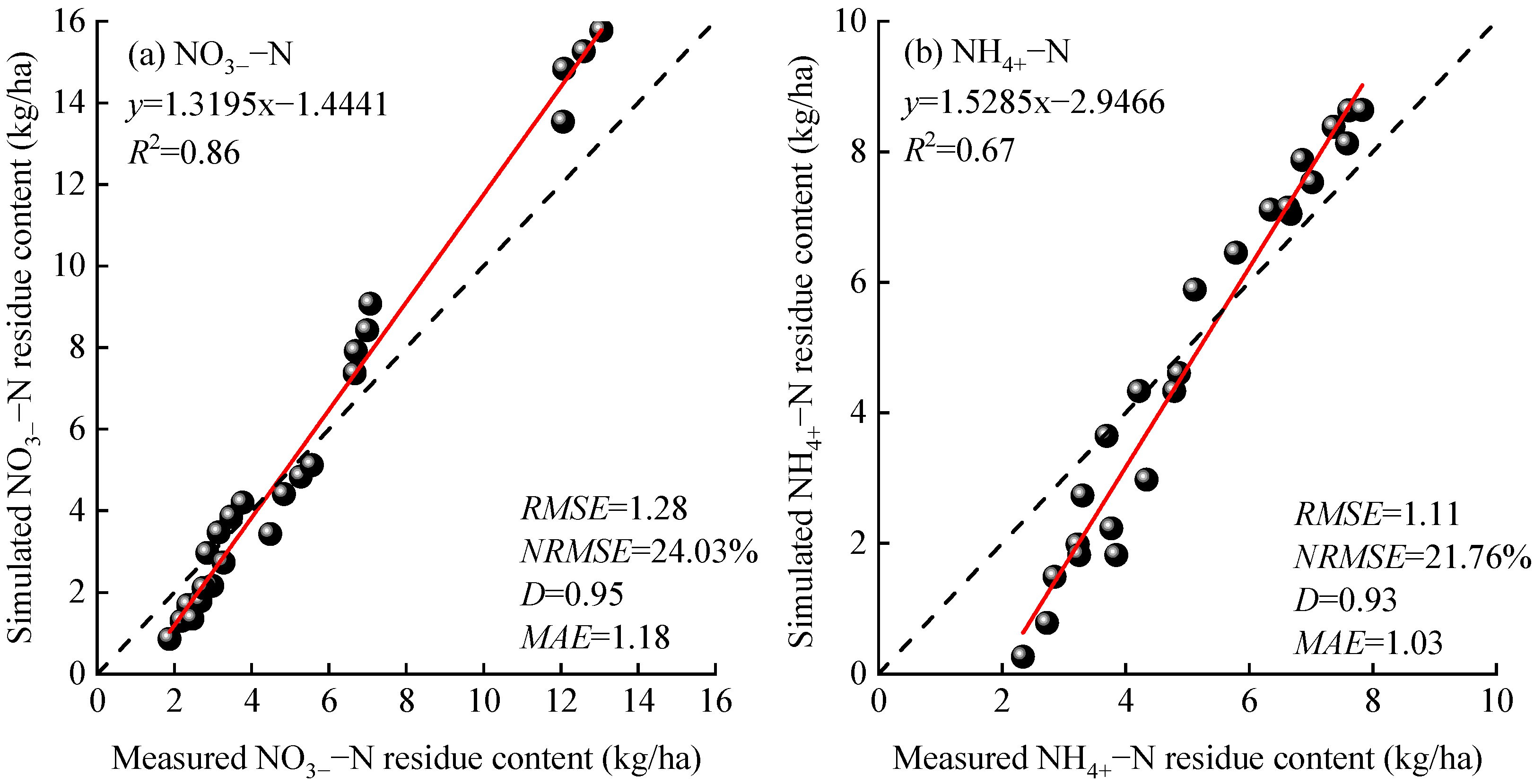

2.1.2. Validation of NO3−–N and NH4+–N Residual Content

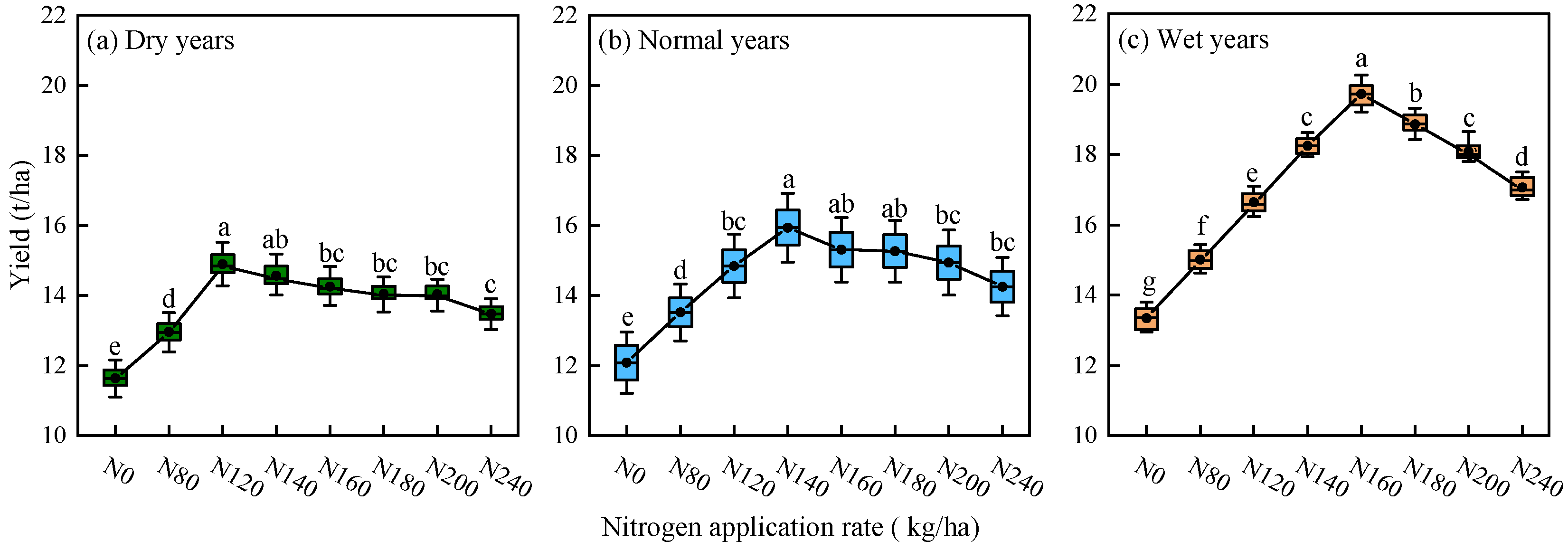

2.1.3. Simulation of Alfalfa Yield Under Different Precipitation Patterns

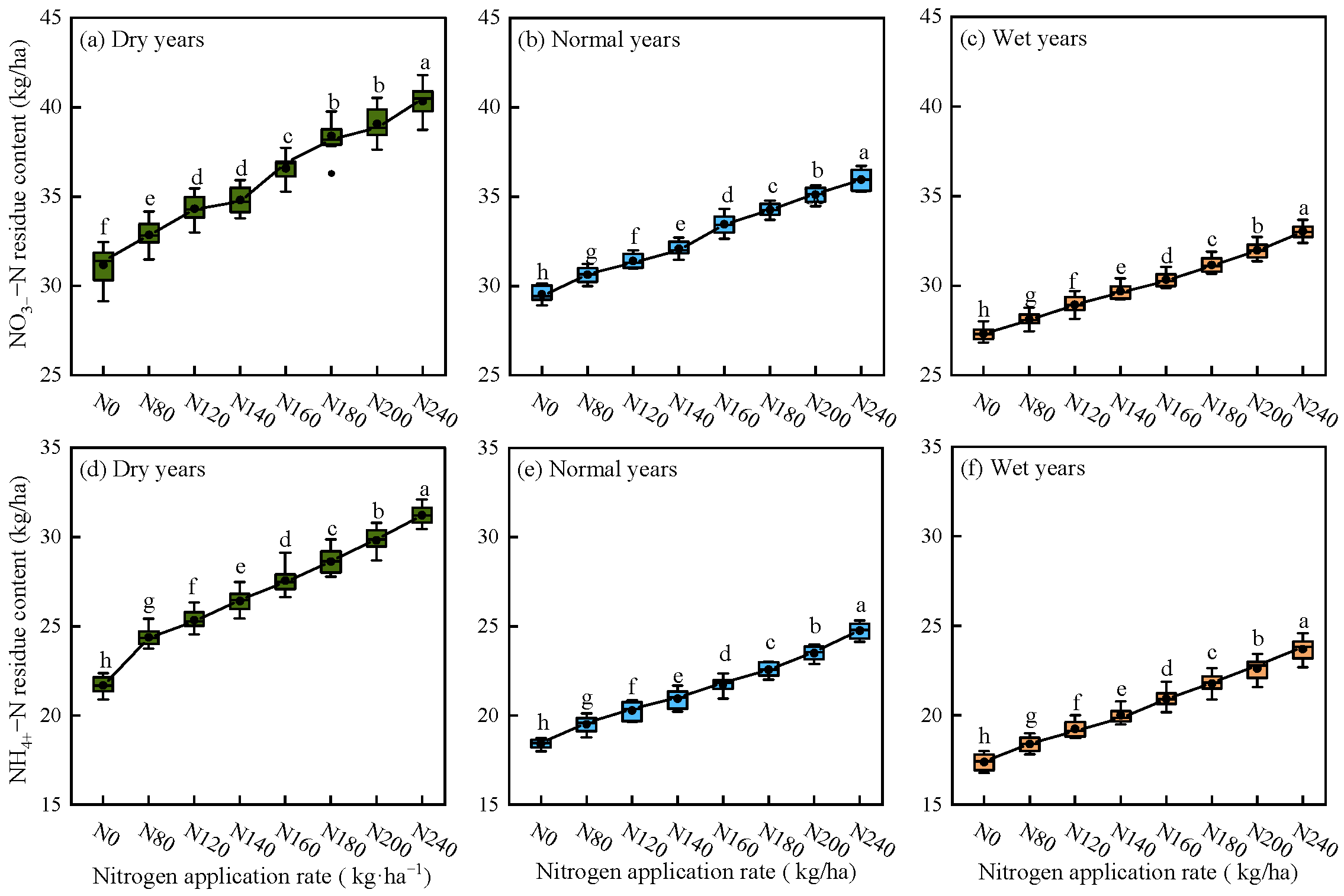

2.1.4. Simulation of Soil NO3−–N and NH4+–N Residuals Under Different Precipitation Patterns

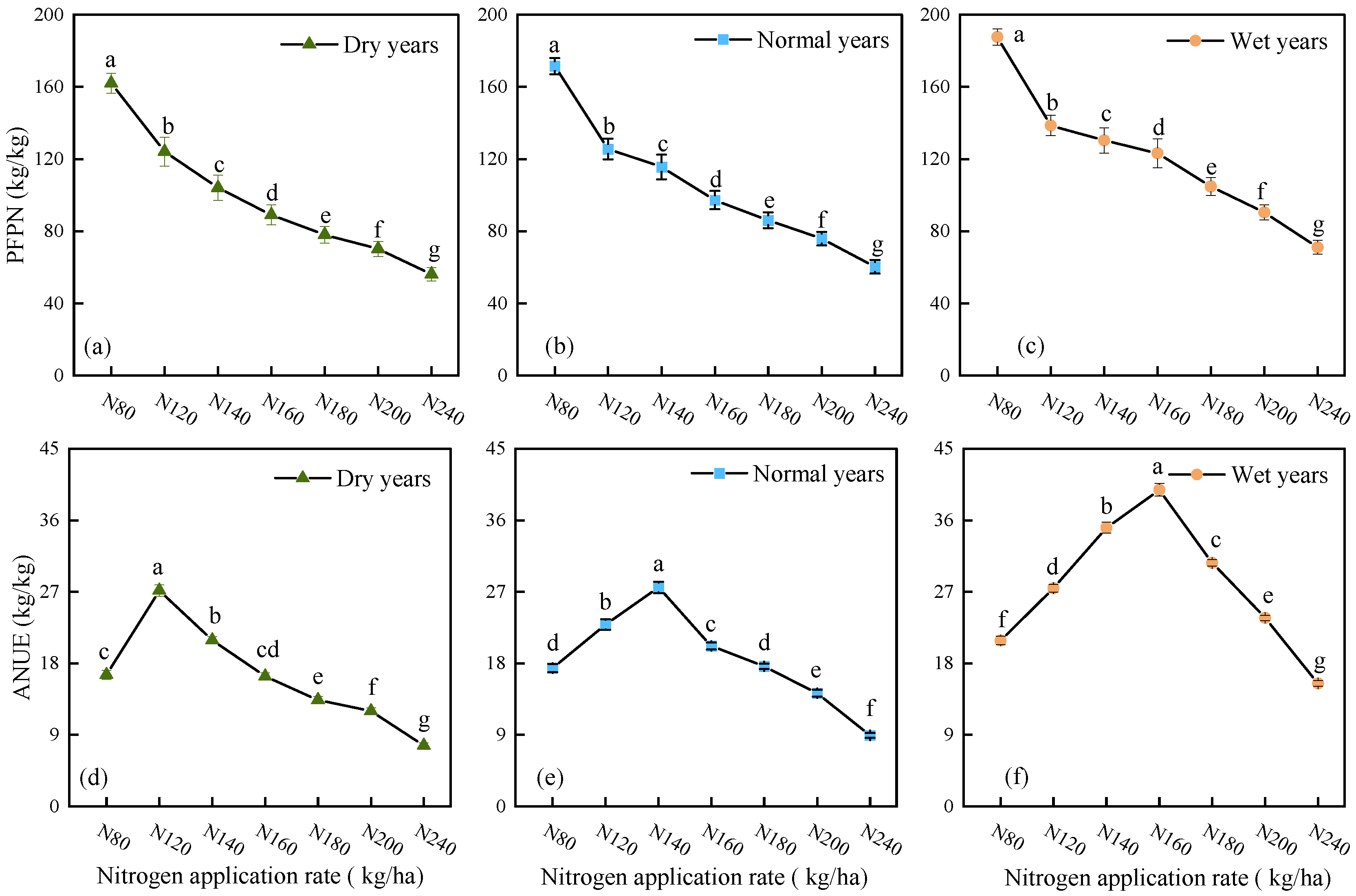

2.2. Alfalfa Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency Under Different Precipitation Patterns

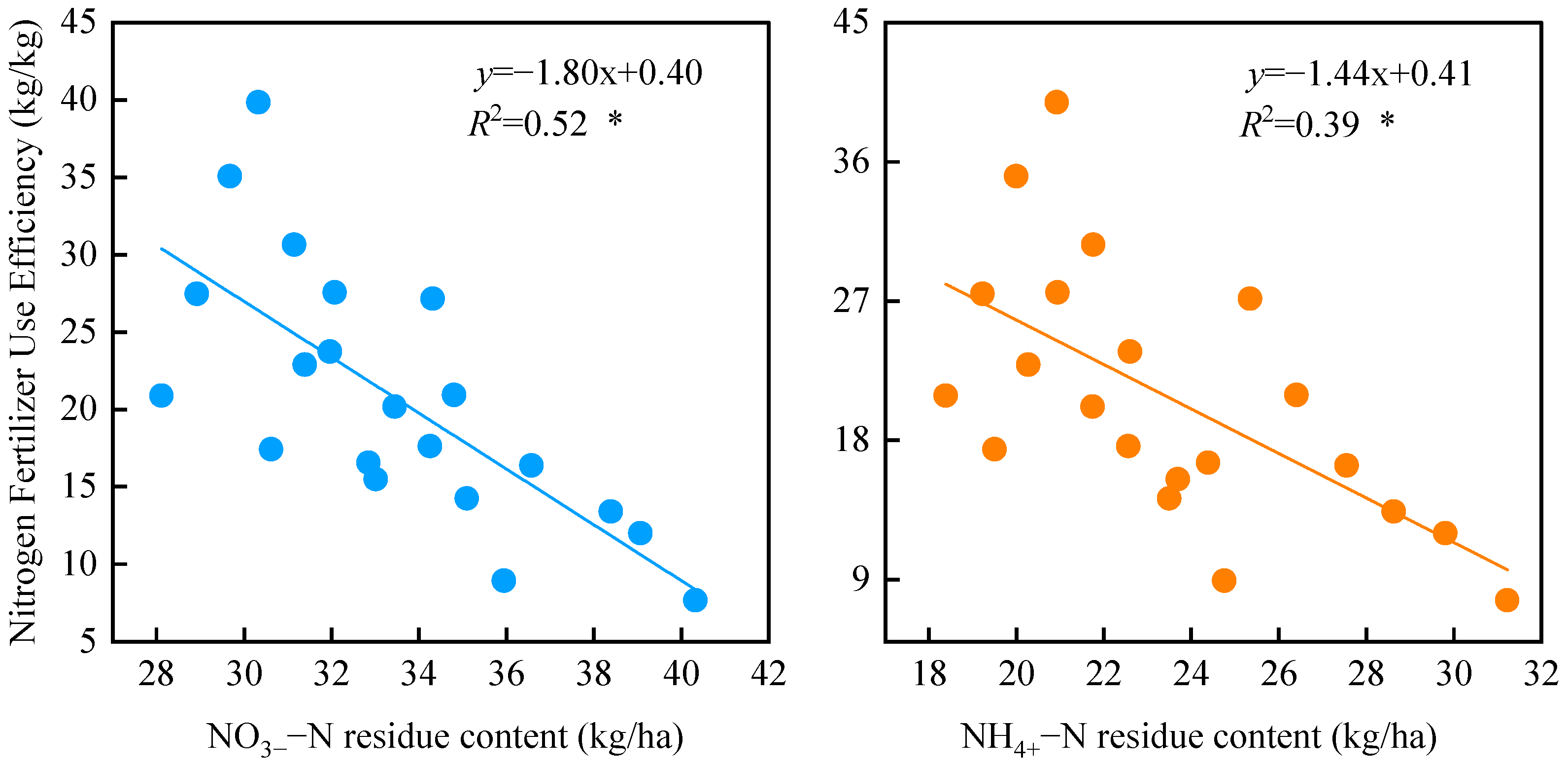

2.3. Correlation Between Soil NO3−–N and NH4+–N Residuals and Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency

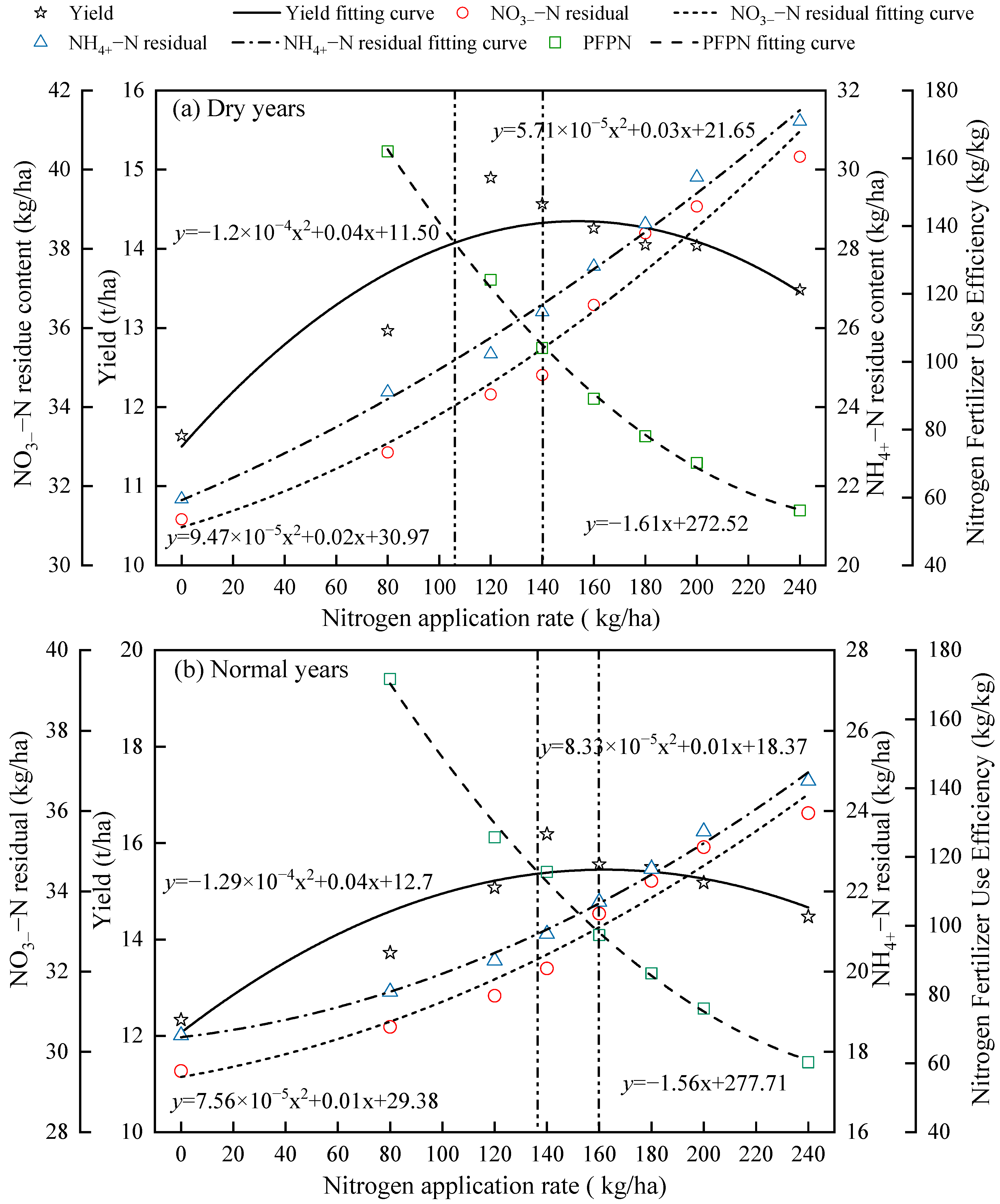

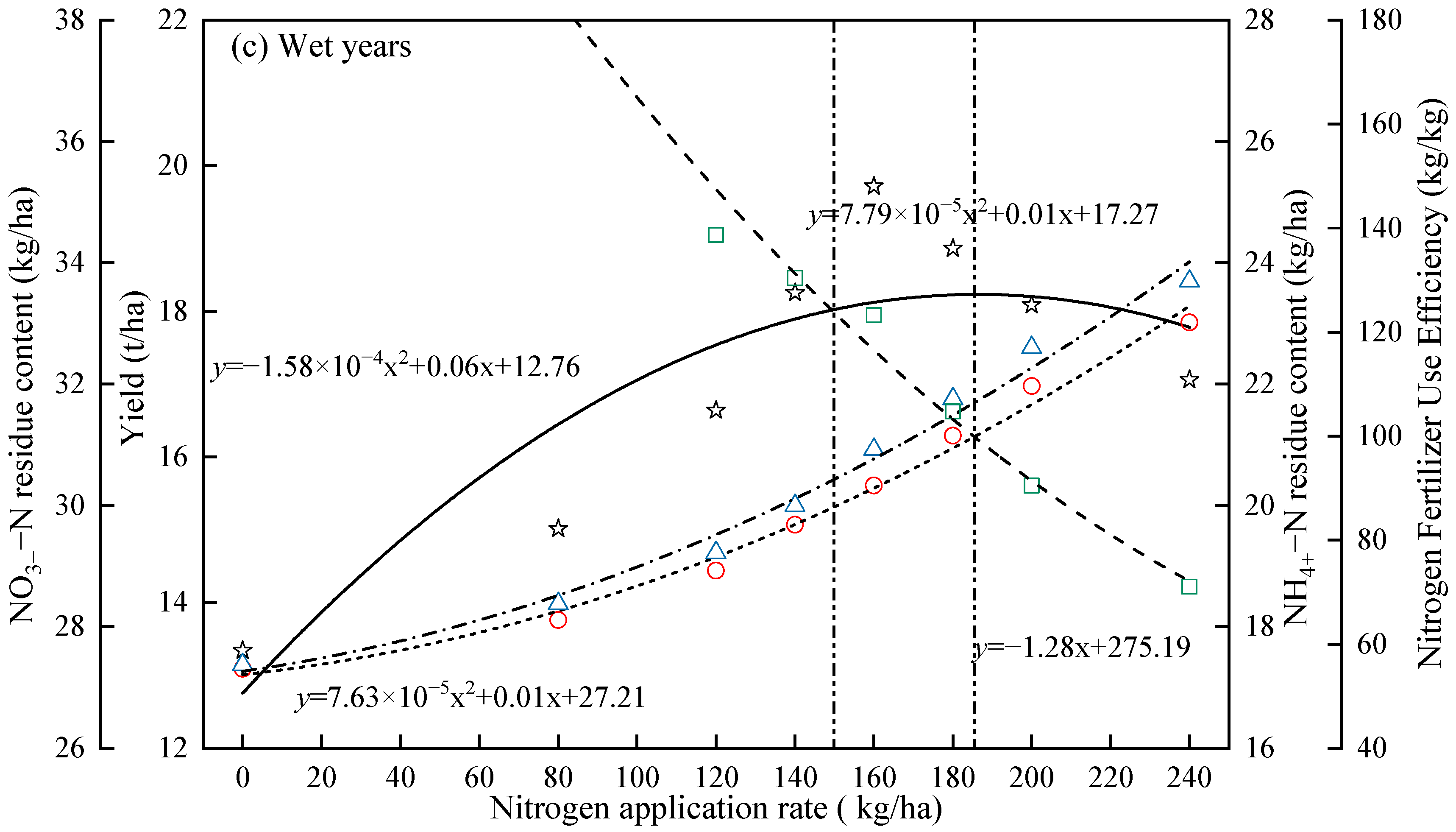

2.4. Interrelationship Among Alfalfa Yield, Soil NO3−–N and NH4+–N Residuals, Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency, and Nitrogen Application Rate

3. Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of Model Adaptability

3.2. Effects of Precipitation Pattern and Nitrogen Application Rate on Soil Nitrogen Residuals

3.3. Effects of Precipitation Pattern and Nitrogen Application Rate on Alfalfa Yield and Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency

4. Materials and Methods

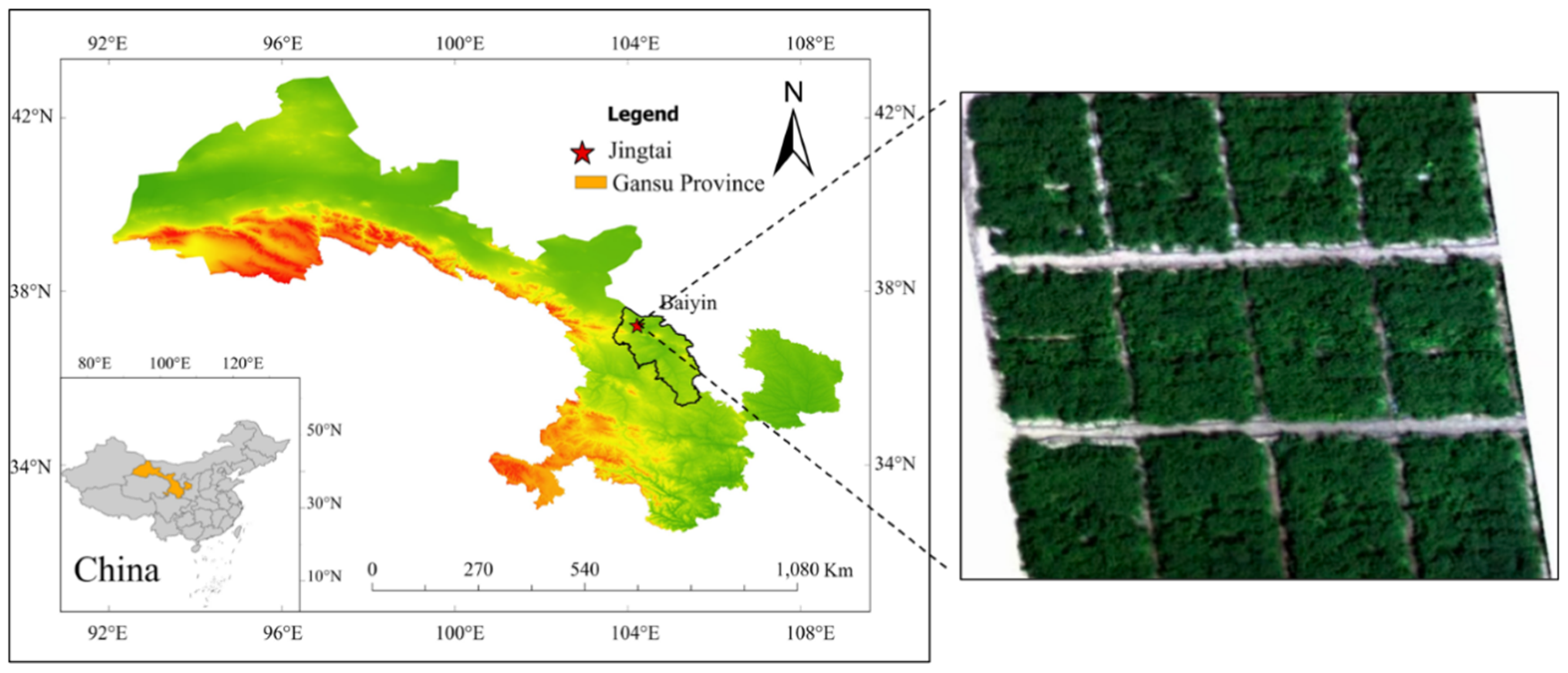

4.1. Description of the Study Area

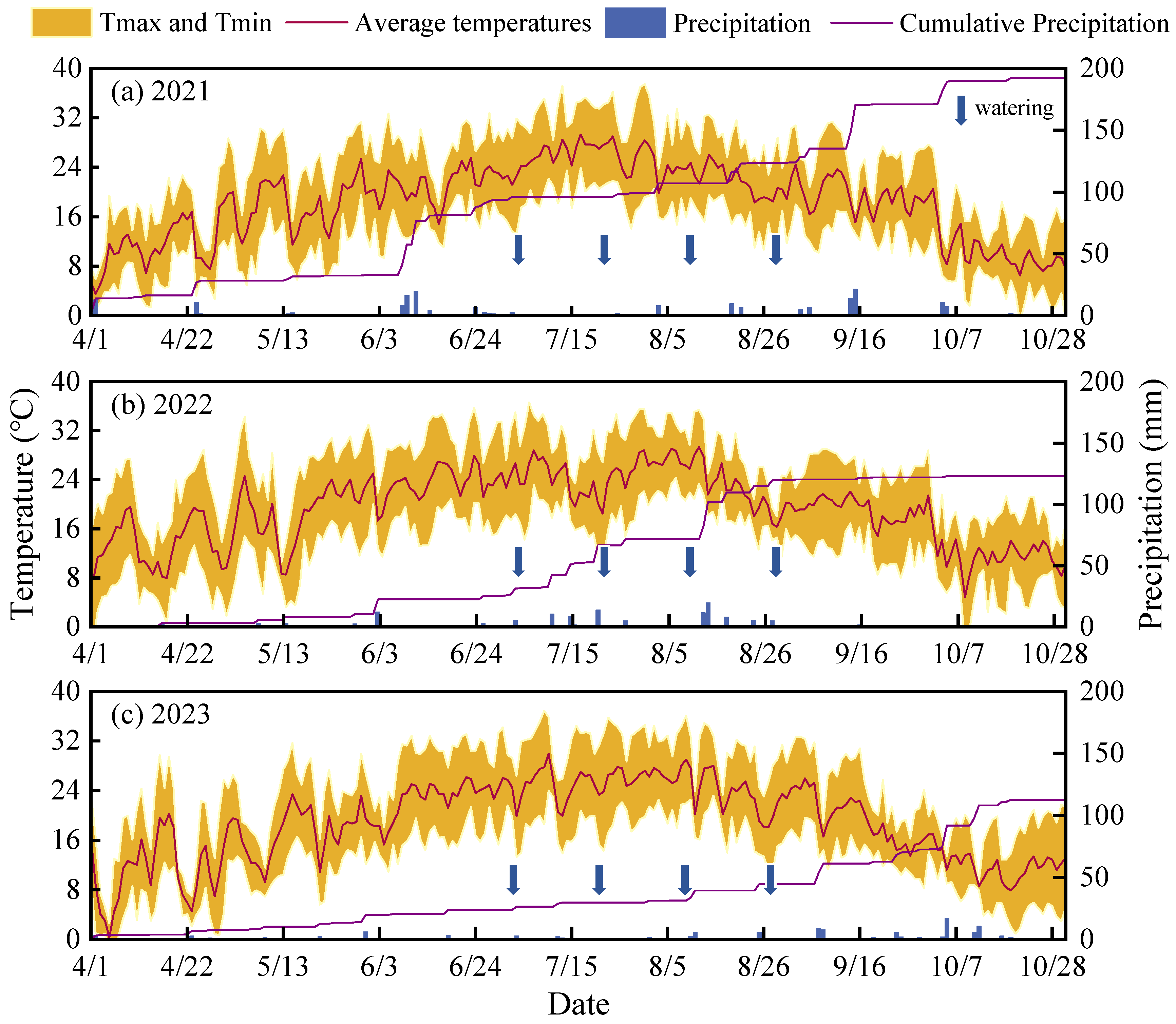

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Measurement Indices and Methods

4.3.1. Soil NO3−–N and NH4+–N Content (mg·kg−1)

4.3.2. Soil NO3−–N and NH4+–N Residual Content (kg/ha)

4.3.3. Yield (Y, t·ha−1)

4.3.4. Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency (NUE)

4.4. Classification of Different Precipitation Patterns

4.5. Scenario Design

4.6. Model Construction and Applicability Verification

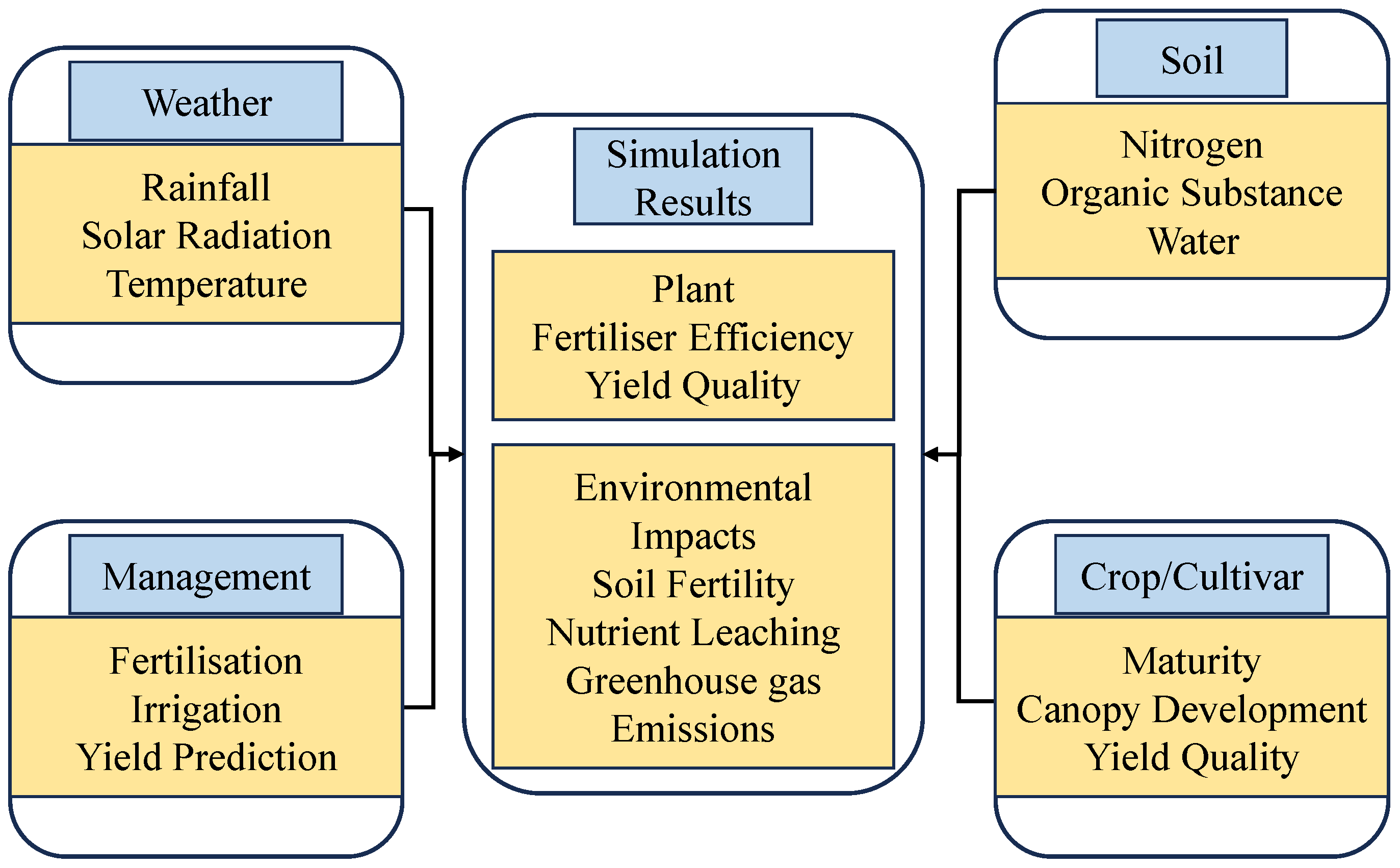

4.6.1. Construction of the APSIM–Lucerne Model

4.6.2. Validation Method

4.7. Data Processing

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The R2 and NRMSE for yield verification of the APSIM–Lucerne model were 0.91 and 6.55%, respectively, while the R2 and NRMSE for NO3−–N and NH4+–N residue verification were 0.67, 0.86, 21.76%, and 24.03%, respectively.

- (2)

- Under different precipitation patterns, alfalfa yield and ANUE exhibited a non-linear response, initially increasing and then decreasing with higher nitrogen application rates. As nitrogen application levels increased, significant accumulation of soil residual NO3−–N and NH4+–N was observed; however, the PFPN consistently declined with increasing nitrogen application rates.

- (3)

- Based on simulations using the calibrated APSIM–Lucerne model, the optimal nitrogen application thresholds for alfalfa under dry, normal, and wet years are in the ranges of 107–140, 135–160, and 150–183 kg/ha, respectively.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, Z.Q.; Sun, D.B.; Wang, Q.S. Study on fertilization types and nitrogen application rates of spring maize in dryland based on APSIM model. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2024, 42, 214–224. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nasrullah, M.; Liang, L.Z.; Rizwanullah, M.; Yu, X.Y.; Majrashi, A.; Alharby, H.F.; Alharbi, B.M.; Fahad, S. Estimating nitrogen use efficiency, profitability, and greenhouse gas emission using different methods of fertilization. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 869873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penuelas, J.; Gargallo-Garriga, A.; Janssens, I.A.; Ciais, P.; Obersteiner, M.; Klem, K.; Urban, O.; Zhu, Y.G.; Sardans, J. Could global intensification of nitrogen fertilisation increase immunogenic proteins and favour the spread of coeliac pathology? Foods 2020, 9, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, Z.; Huang, B.; Lu, C.Y.; Shi, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.Y.; Fang, Y.T. The fate of fertilizer nitrogen in a high nitrate accumulated agricultural soil. Sci. Rep. 2016, 5, 21539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.C.; Guo, T.W.; Liu, G.Y. Effects of different patterns of planting and fertilization on the residual of spring maize soil nitrate nitrogen in dry-land. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2018, 36, 110–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Bai, Z.H.; Velthof, G.L.; Wu, Z.G.; Chadwick, D.; Ma, L. Accumulation and leaching of nitrate in soils in wheat-maize production in China. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 212, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.B.; Xu, X.T.; Zhang, J.Q.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, B.X.; Wang, C.Y.; Xiong, Z.Q. Contributions of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria to nitrous oxide production in intensive greenhouse vegetable fields. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.J.; Li, H.Y.; Duan, Y.Y.; Ling, Y.; Lu, J.D.; Yin, M.H.; Ma, Y.L.; Kang, Y.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Qi, G.P.; et al. Yield increase and emission reduction effects of alfalfa in the Yellow River irrigation district of Gansu Province: The coupling mechanism of biodegradable mulch and controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer. Plants 2025, 14, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.F.; Shen, Y.X.; Li, Z.H.; Qu, H.; Feng, J.X.; Kong, L.N.; Teri, G.; Luan, H.M.; Cao, Z.L. Shade delayed flowering phenology and decreased reproductive growth of Medicago sativa L. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 835380. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.Y.; Jiang, Y.B.; Ling, Y.; Chang, W.J.; Yin, M.H.; Kang, Y.X.; Ma, Y.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Qi, G.P.; Liu, B. Exploring the potential of nitrogen fertilizer mixed application to improve crop yield and nitrogen partial productivity: A meta-analysis. Plants 2025, 14, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zeng, J.; Li, H.; Liu, S.L.; Lei, L.Q.; Liu, S.R. Research advances in the soil nitrogen cycle under global precipitation pattern change. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 7543–7551. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Fu, X.L.; Li, X.Z.; Jia, X.X.; Shao, M.A.; Wei, X.R. Responses of soil nitrogen mineralization during growing season to vegetation and slope position on the northern Loess Plateau of China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2018, 26, 231–241. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.Q.; Zhao, S.Y.; Lin, G.G.; Sun, X.K.; Hu, Y.L. Effects of precipitation change on soil nitrogen mineralization and leaching under Mongolian pine plantation in the Horqin Sandy Lands. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 6564–6572. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cregger, M.A.; McDowell, N.G.; Pangle, R.E.; Pockman, W.T.; Classen, A.T. The impact of precipitation change on nitrogen cycling in a semi-arid ecosystem. Funct. Ecol. 2014, 28, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.L.; Yu, Y.D. Optimizing the irrigation schedule for winter wheat-summer maize using APEX model. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 118–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.X.; Su, J.Y.; Liu, C.J.; Chen, W.H. State and parameter estimation of the AquaCrop model for winter wheat using sensitivity informed particle filter. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180, 105909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, K.; Dutta, S.; Das, S.; Sadhukhan, R. Crop simulation models as decision tools to enhance agricultural system productivity and sustainability–a critical review. Technol. Agron. 2025, 5, e002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.P. Discussion on problems in the development and application of crop growth model. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 36, 1579–1589. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, S.J.; Cheng, H.Q.; Liu, P.; Yang, X. Effects of compound drought and hot events on the forage oats production of Northern Shanxi. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2025; in press. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, E.A.R.; Nunes, M.R. Long-term agro-hydrological simulations of soil water dynamic and maize yield in a tillage chronosequence under subtropical climate conditions. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 229, 105654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Gao, J.H. Optimization of the nitrogen fertilizer schedule of maize under drip irrigation in Jilin, China, based on DSSAT and GA. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 244, 106555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Fraga, H.; van Ieperen, W.; Trindade, H.; Santos, J.A. Effects of climate change and adaptation options on winter wheat yield under rainfed Mediterranean conditions in southern Portugal. Clim. Change 2019, 154, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzworth, D.P.; Huth, N.I.; Devoil, P.G.; Zurcher, E.J.; Herrmann, N.I.; McLean, G.; Chenu, K.; van Oosterom, E.J.; Snow, V.; Murphy, C.; et al. APSIM–Evolution towards a new generation of agricultural systems simulation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 62, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.D.; Liang, J.Y.; Hou, H.Z.; Ma, M.S.; Fang, Y.J.; Liu, Y.L.; Wang, H.L.; Lei, K.N. Modeling optimal nitrogen application rate and placement for maximizing wheat yield in a semi-arid environment using APSIM. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 321, 109896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, P.J.; Biggs, J.S.; Palmer, J.; Meier, E.A.; Verburg, K.; Skocaj, D.M. Prioritizing crop management to increase nitrogen use efficiency in Australian sugarcane crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Cheng, C.; Yang, F.Y.; Fan, D.L.; Luo, J.M.; Han, J.R.; Wang, T.S.; Guo, E.J. Optimization of water and nitrogen management mode for spring wheat under different precipitation year types based on APSIM model. J. Triticeae Crops 2025, 45, 103–111. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.J.; Liu, Q. Simulation of spring wheat yield response to precipitation change, nitrogen application and straw mulching under different precipitation years. Crops, 2025; in press. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.B.; Feng, W.Z.; Qu, M.Y.; Feng, H.; Yu, Q.; He, J.Q. Influences of climate change on productivity of winter wheat and summer maize rotation system in Huang–Huai–Hai Plain. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 429–445. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, M.H.; Jiang, Y.B.; Ling, Y.; Ma, Y.L.; Qi, G.P.; Kang, Y.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Lu, Q.; Shang, Y.J.; Fan, X.R.; et al. Optimizing lucerne productivity and resource efficiency in China’s Yellow River irrigated region: Synergistic effects of ridge–film mulching and controlled--release nitrogen fertilization. Agriculture 2025, 15, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Luo, D.; Chai, X.T.; Wu, Y.G.; Wang, Y.R.; Nan, Z.B.; Yang, Q.C.; Liu, W.X.; Liu, Z.P. Multiple regulatory networks are activated during cold stress in Medicago sativa L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.N.; Luo, Z.Z.; Cai, L.Q.; Coulter, J.A.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Berti, M. Continuous monoculture of alfalfa and annual crops influence soil organic matter and microbial communities in the rainfed Loess Plateau of China. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.J.; Han, C.L.; Kong, M.; Shi, X.Y.; Zdruli, P.; Li, F.M. Plastic film mulch promotes high alfalfa production with phosphorus saving and low risk of soil nitrogen loss. Field Crops Res. 2018, 229, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulnazaer, A.; Tao, H.N.; Wang, Z.K.; Shen, Y.Y. Evaluating the deep-horizon soil water content and water use efficiency in the alfalfa-wheat rotation system on the dryland of Loess Plateau using APSIM. Acta Pratac. Sin. 2021, 30, 22–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.K.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, X.M.; Shen, Y.Y. Effects of precipitation and air temperature changes on yield of several crops in Eastern Gansu of China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 106–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Niu, S.S.; Hou, Q.Q.; Yang, X.; Xu, H.Y. The response of alfalfa production in Jinzhong Basin, Shanxi Province to water and air temperature. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2024, 32, 207–218. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T. Simulating yield and water use of a sorghum-cowpea intercrop using APSIM. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 177, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukr, H.H.; Pembleton, K.; Zull, A.; Cockfield, G. Impacts of Effects of Deficit Irrigation Strategy on Water Use Efficiency and Yield in Cotton under Different Irrigation Systems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, N.; Li, J.M.; Ma, Y.B.; Ullah, A.; Zhu, P.; Peng, C.; Hussain, B.; Danish, S. 20 Years nitrogen dynamics study by using APSIM nitrogen model simulation for sustainable management in Jilin China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, S.G.; Motsa, N.M.; Magwaza, L.S.; Ncama, K.; Sithole, N.J. Effects of different tillage practices and nitrogen fertiliser application rates on soil-available nitrogen. Agronomy 2023, 13, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Sun, S.N.; Liu, W.T.; Zhu, L.; Yan, X.B. Different forms and proportions of exogenous nitrogen promote the growth of alfalfa by increasing soil enzyme activity. Plants 2022, 11, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasielski, J.; Earl, H.; Deen, B. Luxury vegetative nitrogen uptake in maize buffers grain yield under post-silking water and nitrogen stress: A mechanistic understanding. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.F.; Ye, C.H.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.H.; Li, H.H.; Yang, D.H.; Ahmed, W.; Zhao, Z.X. Elucidating the impact of biochar with different carbon/nitrogen ratios on soil biochemical properties and rhizosphere bacterial communities of flue-cured tobacco plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1250669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Z.; Dijkstra, F.A.; Liu, X.R.; Wang, Y.D.; Huang, J.; Lu, N. Effects of biochar on soil microbial biomass after four years of consecutive application in the North China Plain. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.Q.; Ma, K.; Jia, B.; Wei, X.; Yun, B.Y.; Ma, J.Z.; Zhang, H.; Ji, L.; Li, J.R. Soil nitrate-N distribution, leaching loss and nitrogen uptake and utilization of maize under drip irrigation in different precipitation years. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2023, 31, 765–775. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.Y. Effects of Reduced Nitrogen Application on Soil Water and Fertilizer Utilization, Yield and Nitrogen Balance of Winter Wheat in Dryland. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hao, K.; Fei, L.J.; Liu, L.H.; Jie, F.L.; Peng, Y.L.; Liu, X.G.; Khan, S.A.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.K. Comprehensive evaluation on the yield, quality, and water-nitrogen use efficiency of mountain apple under surge-root irrigation in the Loess Plateau based on the improved TOPSIS method. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 853546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.Y.; Sun, H.M.; Yang, Y.R.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; Qiao, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhang, K.; Bai, Z.Y.; Li, A.C.; et al. Long-term nitrogen fertilizer management for enhancing use efficiency and sustainable cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1271846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.R.; Zhang, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, Y.M.; Deng, W.H.; Liu, S.P.; Sun, L.Z. Effect of the level of nitrogen supply on the growth resilience of Medicago sativa after rewatering. Pratac. Sci. 2024, 41, 620–627. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.L.; Huang, S.B.; Tian, B.; Ren, J.H.; Meng, Q.F.; Wang, P. Manipulating planting density and nitrogen fertilizer application to improve yield and reduce environmental impact in Chinese maize production. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, D.; Thakur, M.; Joshi, R.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R. Agro-climatic suitability evaluation for saffron production in areas of Western Himalaya. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 657819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.W.; Ding, X.Y.; Xu, J.S.; Ye, P.; He, J.K.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, B.B.; Zhang, X.K. Effects of nitrogen application on nitrogen use efficiency and economic benefits of rapeseed under different precipitation years. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2024, 46, 92–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ru, X.Y.; Li, G.; Chen, G.P.; Zhang, T.S.; Yan, L.J. Regulation effects of water and nitrogen on wheat yield and biomass in different precipitation years. Acta Agron. Sin. 2019, 45, 1725–1734. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Olmedo, M.; Ortiz, M.; Selles, G. Effects of transient soil waterlogging and its importance for rootstock selection. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 75, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamljen, T.; Lojen, S.; Zupanc, V.; Slatnar, A. Determination of the yield, enzymatic and metabolic response of two Capsicum spp. cultivars to deficit irrigation and fertilization using the stable isotope 15N. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Qi, G.P.; Yin, M.H.; Kang, Y.X.; Ma, Y.L.; Jia, Q.; Wang, J.H.; Jiang, Y.B.; Wang, C.; Gao, Y.L.; et al. Alfalfa cultivation patterns in the Yellow River irrigation area on soil water and nitrogen use efficiency. Agronomy 2024, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambouris, A.N.; Zebarth, B.J.; Nolin, M.C.; Laverdière, M.R. Apparent fertilizer nitrogen recovery and residual soil ni-trate under continuous potato cropping: Effect of N fertilization rate and timing. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2008, 88, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.R.; Wang, J.H.; Yin, M.H.; Ma, Y.L.; Jia, Q.; Kang, Y.X.; Qi, G.P.; Gao, Y.L.; Jiang, Y.B.; Li, H.Y.; et al. Investigation of the regulatory effects of water and nitrogen supply on nitrogen transport and distribution in wolfberry fields. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1385980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q. Simulation of response of spring wheat yield and its components to sowing date and average daily temperature in dryland under different precipitation years. J. Triticeae Crops 2024, 44, 1474–1481. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H.Y.; Liu, Q. Impact of irrigation regimes on yield and water use efficiency of spring wheat under different precipitation years based on the APSIM model. Softw. Eng. 2025, 28, 67–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lagerquist, E.; Vogeler, I.; Kumar, U.; Bergkvist, G.; Lana, M.; Watson, C.A.; Parsons, D. Assessing the effect of intercropped leguminous service crops on main crops and soil processes using APSIM NG. Agric. Syst. 2024, 216, 103884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Huang, G.B.; Bellotti, W.; Chen, W. Adaptation research of APSIM model under different tillage systems in the Loess hill-gullied region. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009, 29, 2655–2663. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)?–arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, M.V.; Brebels, A.; Shcherbakova, N.L.; Tyukov, A.P.; Janovsky, T.A.; Kamaev, V.A. A survey of forecast error measures. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 24, 171–176. [Google Scholar]

| Model Year | Average Precipitation in Growth Period (mm) | Years | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry year | 135.10 | 13 | 2000, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2020, 2022, 2023 |

| Normal year | 212.25 | 2 | 2001, 2021 |

| Wet year | 271.31 | 10 | 2002, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2024 |

| Parameters | Soil Layer (cm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–20 | 20–40 | 40–60 | 60–80 | 80–100 | 100–120 | |

| BD (g/cm3) | 1.270 | 1.350 | 1.280 | 1.140 | 1.240 | 1.300 |

| SAT (mm/mm) | 0.460 | 0.431 | 0.467 | 0.520 | 0.482 | 0.459 |

| DUL (mm/mm) | 0.197 | 0.213 | 0.241 | 0.278 | 0.233 | 0.253 |

| LL15 (mm/mm) | 0.061 | 0.069 | 0.075 | 0.086 | 0.072 | 0.078 |

| Air dry (mm/mm) | 0.010 | 0.030 | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.070 |

| Soil pH | 8.095 | 8.120 | 8.410 | 8.540 | 8.700 | 8.700 |

| Swcon (0–1) | 0.600 | 0.600 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 |

| LucerneLL (mm/mm) | 0.290 | 0.290 | 0.300 | 0.310 | 0.320 | 0.330 |

| LucerneKL (d−1) | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090 |

| LucerneXF (0–1) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Parameters | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| tt_emerg_to_endjuv | 550 | °C·d |

| tt_endjuv_to_init | 610 | °C·d |

| tt_endjuv_to_init | 260 | °C·d |

| Photoperiod required for floral initiation | >10 | h |

| Radiation use efficiency | 1.8 | g/MJ |

| Stem weight | 0~5 | g/plant |

| Plant height | 0~5000 | mm |

| Summer_U | 6 | mm |

| Summer Cona | 3.5 | mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Chen, J.; Yin, M.; Kang, Y.; Qi, G.; Ma, Y.; Xie, B.; et al. Optimal Nitrogen Application Strategies for Alfalfa Under Different Precipitation Patterns: Balancing Yield, Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency, and Soil Nitrogen Residue. Plants 2026, 15, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020333

Wang Y, Jiang Y, Li H, Li B, Chen J, Yin M, Kang Y, Qi G, Ma Y, Xie B, et al. Optimal Nitrogen Application Strategies for Alfalfa Under Different Precipitation Patterns: Balancing Yield, Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency, and Soil Nitrogen Residue. Plants. 2026; 15(2):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020333

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yanbiao, Yuanbo Jiang, Haiyan Li, Boda Li, Jinxi Chen, Minhua Yin, Yanxia Kang, Guangping Qi, Yanlin Ma, Bojie Xie, and et al. 2026. "Optimal Nitrogen Application Strategies for Alfalfa Under Different Precipitation Patterns: Balancing Yield, Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency, and Soil Nitrogen Residue" Plants 15, no. 2: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020333

APA StyleWang, Y., Jiang, Y., Li, H., Li, B., Chen, J., Yin, M., Kang, Y., Qi, G., Ma, Y., Xie, B., Jin, H., Wu, T., & Li, S. (2026). Optimal Nitrogen Application Strategies for Alfalfa Under Different Precipitation Patterns: Balancing Yield, Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency, and Soil Nitrogen Residue. Plants, 15(2), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020333