CDE6 Regulates Chloroplast Ultrastructure and Affects the Sensitivity of Rice to High Temperature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

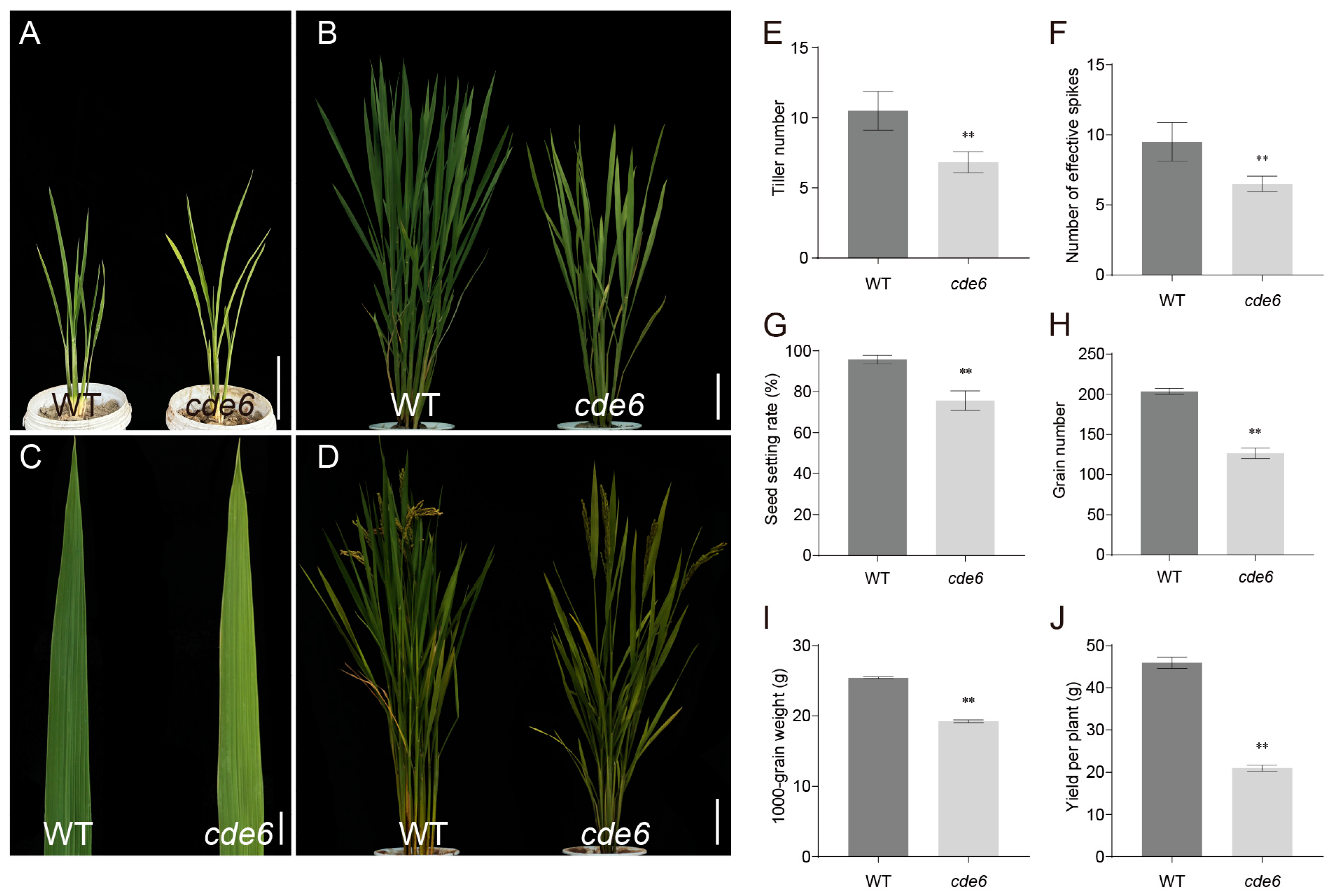

2.1. Phenotypic Analysis of cde6 Mutant Rice

2.2. Defects in Chloroplast Structure and Photosynthesis of cde6 Mutant

2.3. Expression of Chloroplast Development Genes in WT and cde6 Mutant Plants

2.4. Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species in cde6

2.5. MutMap-Based Gene Mapping of CDE6

2.6. Expression Pattern Analysis and Subcellular Localization of CDE6

2.7. The cde6 Mutant Is Sensitive to High Temperatures

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growing Conditions

4.2. Agronomic Trait Evaluation

4.3. Measurement of Chlorophyll Content

4.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Observation

4.5. Determination of Physiological Indices

4.6. Gene Mapping

4.7. Subcellular Localization

4.8. CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout of cde6

4.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.10. Seedling-Stage High-Temperature Treatment

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stern, D.B.; Goldschmidt-Clermont, M.; Hanson, M.R. Chloroplast RNA Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 125–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, K.-C.; Kang, Y.; Song, J.-H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, C.; Tai, T.H.; Park, I.; Ahn, S.-N. A Frameshift Mutation in the Mg-Chelatase I Subunit Gene OsCHLI Is Associated with a Lethal Chlorophyll-Deficient, Yellow Seedling Phenotype in Rice. Plants 2023, 12, 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.J.; Zhang, H.Q.; Wang, Y.; He, F.; Liu, J.L.; Xiao, X.; Shu, Z.F.; Li, W.; Wang, G.H.; Wang, G.L. Mapped Clone and Functional Analysis of Leaf-Color Gene Ygl7 in a Rice Hybrid. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Tabassum, J.; Sheng, Z.; Lv, Y.; Chen, W.; Zeb, A.; Dong, N.; Ali, U.; Shao, G.; Wei, X.; et al. Loss-of-Function of PGL10 Impairs Photosynthesis and Tolerance to High-Temperature Stress in Rice. Physiol. Plant 2024, 176, e14369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.-F.; Kan, Y.; Shan, J.-X.; Ye, W.-W.; Dong, N.-Q.; Guo, T.; Xiang, Y.-H.; Yang, Y.-B.; Li, Y.-C.; et al. A Genetic Module at One Locus in Rice Protects Chloroplasts to Enhance Thermotolerance. Science 2022, 376, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, S.; Siegel, A.; Shan, S.-o.; Grimm, B.; Wang, P. Chloroplast SRP43 Autonomously Protects Chlorophyll Biosynthesis Proteins Against Heat Shock. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 1420–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Feng, L.; Alyafei, M.A.M.; Jaleel, A.; Ren, M. Function of Chloroplasts in Plant Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Mesihovic, A.; Chaturvedi, P.; Ghatak, A.; Weckwerth, W.; Böhmer, M.; Schleiff, E. Structural and Functional Heat Stress Responses of Chloroplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes 2020, 11, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Gelani, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Heat Tolerance in Plants: An Overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Kreslavski, V.D.; Klimov, V.V.; Los, D.A.; Carpentier, R.; Mohanty, P. Heat stress: An Overview of Molecular Responses in Photosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 2008, 98, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zeng, J.; Xu, Z.; Yuan, M.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Diao, X.; Gong, S.; Yang, F.; et al. OsPPR8, a Pentatricopeptide Repeat Protein, Regulates Splicing of Mitochondrial Nad2 Intron 3 to Affect Grain Quality and High-Temperature Tolerance in Rice. Plant J 2025, 122, e70246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, J.; Lu, H.P.; Liu, J.X. The Hot Science in Rice Research: How Rice Plants Cope with Heat Stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1087–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-X.; Cao, Y.-J.; Yang, Y.-B.; Shan, J.-X.; Ye, W.-W.; Dong, N.-Q.; Kan, Y.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Lu, Z.-Q.; Guo, S.-Q.; et al. A TT1–SCE1 Module Integrates Ubiquitination and SUMOylation to Regulate Heat Tolerance in Rice. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 1899–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Y.; Mu, X.-R.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Shan, J.-X.; Ye, W.-W.; Lin, H.-X. TT2 Controls Rice Thermotolerance Through SCT1-Dependent Alteration of Wax Biosynthesis. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, K.; Hu, C.; Abbas, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, P.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, J.; Yin, W.; Shalmani, A.; et al. A Natural Gene on-Off System Confers Field Thermotolerance for Grain Quality and Yield in Rice. Cell 2025, 188, 3661–3678.e3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Cha, J.; Choi, C.; Choi, N.; Ji, H.S.; Park, S.R.; Lee, S.; Hwang, D.J. Rice WRKY11 Plays a Role in Pathogen Defense and Drought Tolerance. Rice 2018, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhong, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Ye, H.; Fang, Y.; et al. WLP3 Encodes the Ribosomal Protein L18 and Regulates Chloroplast Development in Rice. Rice 2023, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, J.; Zu, X.; Gong, J.; Deng, H.; Hang, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Deng, X.; Luo, L.; et al. Pseudouridylation of Chloroplast Ribosomal RNA Contributes to Low Temperature Acclimation in Rice. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Lin, Q.; Zhou, C.; Liu, X.; Miao, R.; Ma, T.; Chen, Y.; Mou, C.; Jing, R.; Feng, M.; et al. Young Leaf White Stripe Encodes a P-Type PPR Protein Required for Chloroplast Development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1687–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, L.; Fang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Gong, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, C.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Accumulation of the RNA Polymerase Subunit RpoB Depends on RNA Editing by OsPPR16 and Affects Chloroplast Development During Early Leaf Development in Rice. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, T.; Huang, Y.; Chen, G.; Xu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. The Pentatricopeptide Repeat Protein AL5 Modulates Early Chloroplast Development in Rice. Crop J 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z. Chlorosis Seedling Lethality 1 Encoding a MAP3K Protein Is Essential for Chloroplast Development in Rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Ouyang, M.; Li, Q.; Zou, M.; Guo, J.; Ma, J.; Lu, C.; Zhang, L. The Arabidopsis Chloroplast Ribosome Recycling Factor Is Essential for Embryogenesis and Chloroplast Biogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 74, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, N.; Janosi, L.; Block, M.A.; Shuda, M.; Teyssier, E.; Miege, C.; Cheniclet, C.; Carde, J.P.; Kaji, A.; Joyard, J. Plant Ribosome Recycling Factor Homologue Is a Chloroplastic Protein and Is Bactericidal in Escherichia Coli Carrying Temperature-Sensitive Ribosome Recycling Factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5464–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-R.; An, G. Rice Chloroplast-Localized Heat Shock Protein 70, OsHsp70CP1, Is Essential for Chloroplast Development under High-Temperature Conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 854–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, A.; Ruan, B.; Hu, H.; Guo, R.; Chen, J.; Qian, Q.; Gao, Z. Identification of Green-Revertible Yellow 3 (GRY3), Encoding a 4-Hydroxy-3-Methylbut-2-Enyl Diphosphate Reductase Involved in Chlorophyll Synthesis Under High Temperature and High Light in Rice. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yi, Q.; Liu, J.; Dong, G.; Guo, L.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Hu, J.; Ren, D.; Zhang, Q.; et al. PGL13, a Novel Allele of OsCRTISO, Containing a Polyamine Oxidase Domain, Affects Chloroplast Development and Heat Stress Response in Rice. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 104, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Chen, D.; He, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ren, D.; Qian, Q.; Guo, L.; et al. The Rice White Green Leaf 2 Gene Causes Defects in Chloroplast Development and Affects the Plastid Ribosomal Protein S9. Rice 2018, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ai, P. A Chloroplast-Localized Pentatricopeptide Repeat Protein Involved in RNA Editing and Splicing and Its Effects on Chloroplast Development in Rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, G.; Liu, N.a.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Zhao, D. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Yellow Leaf Mutant Yl1 in Rice. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 91, 2419–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, D.; Pan, X.; Dong, Y. The Rice YL4 Gene Encoding a Ribosome Maturation Domain Protein Is Essential for Chloroplast Development. Biology 2024, 13, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-W.; Zhang, T.-Q.; Xing, Y.-D.; Zeng, X.-Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.-X.; Shi, J.-Q.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.-F.; et al. YGL9, Encoding the Putative Chloroplast Signal Recognition Particle 43 kDa Protein in Rice, Is Involved in Chloroplast Development. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Yang, C.-M.; Shih, T.-H.; Lin, S.-H.; Pham, G.; Nguyen, H.C. Chlorophyll Biosynthesis and Transcriptome Profiles of Chlorophyll B-Deficient Type 2b Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2021, 49, 12380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, K. Production and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Chloroplasts and Their Functions. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphylidès, C.; Krischke, M.; Hoeberichts, F.A.; Ksas, B.; Gresser, G.; Havaux, M.; Van Breusegem, F.; Mueller, M.J. Singlet Oxygen is the Major Reactive Oxygen Species Involved in Photooxidative Damage to Plants. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Xiao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Qin, C.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Sang, X.; Ling, Y.; et al. ABERRANT CARBOHYDRATE PARTITIONING 1 Modulates Sucrose Allocation by Regulating Cell Wall Formation in Rice. Plant J. 2025, 123, e70430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Liu, J.; Yun, H.; Du, D.; Zhong, X.; Yang, Z.; Sang, X.; Zhang, C. Characterization and Candidate Gene Analysis of the Yellow-Green Leaf Mutant ygl16 in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 90, 1103–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tang, L.; Li, Q.; Cai, Y.; Ahmad, S.; Wang, Y.; Tang, S.; Guo, N.; Wei, X.; Tang, S.; et al. YGL3 Encoding an IPP and DMAPP Synthase Interacts with OsPIL11 to Regulate Chloroplast Development in Rice. Rice 2024, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Cao, R.; Jiao, G.; Hu, S.; Shao, G.; Sheng, Z.; Xie, L.; Tang, S.; Wei, X.; et al. CDE4 Encodes a Pentatricopeptide Repeat Protein Involved in Chloroplast RNA Splicing and Affects Chloroplast Development Under Low-Temperature Conditions in Rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 1724–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Shao, G.; Qiu, J.; Jiao, G.; Sheng, Z.; Xie, L.; Wu, Y.; Tang, S.; Wei, X.; Hu, P. White Leaf and Panicle 2, Encoding a PEP-Associated Protein, Is Required for Chloroplast Biogenesis Under Heat Stress in Rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5147–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Nie, W.; Lin, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, D.; Qian, Q.; Zhu, L. FRUCTOKINASE-LIKE PROTEIN 1 Interacts with TRXz to Regulate Chloroplast Development in Rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Kang, S.; He, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, S.; Hu, J.; Zeng, D.; Zhang, G.; Dong, G.; Gao, Z.; et al. The Newly Identified Heat-Stress Sensitive Albino 1 Gene Affects Chloroplast Development in Rice. Plant Sci. 2018, 267, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushi, Y.; Yokochi, Y.; Hisabori, T.; Yoshida, K. Plastidial Thioredoxin-Like Proteins Are Essential for Normal Embryogenesis and Seed Development in Arabidopsis Thaliana. J. Plant Res. 2025, 138, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrási, N.; Pettkó-Szandtner, A.; Szabados, L. Diversity of Plant Heat Shock Factors: Regulation, Interactions, and Functions. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 1558–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Xiong, L.; Shi, H.; Yang, S.; Herrera-Estrella, L.R.; Xu, G.; Chao, D.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.Y.; Qin, F.; et al. Plant Abiotic Stress Response and Nutrient Use Efficiency. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohama, N.; Sato, H.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Transcriptional Regulatory Network of Plant Heat Stress Response. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, K.D.; Berberich, T.; Ebersberger, I.; Nover, L. The Plant Heat Stress Transcription Factor (Hsf) Family: Structure, Function and Evolution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1819, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuchun, R.A.O.; Ran, J.; Sheng, W.; Xianmei, W.U.; Hanfei, Y.E.; Chenyang, P.A.N.; Sanfeng, L.I.; Dedong, X.; Weiyong, Z.; Gaoxing, D.A.I.; et al. SPL36 Encodes a Receptor-like Protein Kinase that Regulates Programmed Cell Death and Defense Responses in Rice. Rice 2021, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.; Kosugi, S.; Yoshida, K.; Natsume, S.; Takagi, H.; Kanzaki, H.; Matsumura, H.; Yoshida, K.; Mitsuoka, C.; Tamiru, M.; et al. Genome Sequencing Reveals Agronomically Important Loci in Rice Using MutMap. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, J.; Duan, S.; Ao, Y.; Dai, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Feng, D.; et al. A highly Efficient Rice Green Tissue Protoplast System for Transient Gene Expression and Studying Light/Chloroplast-Related Processes. Plant Methods 2011, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Li, B.; Qi, P.; Yin, W.; Xu, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Gu, X.; Hu, Y. CDE6 Regulates Chloroplast Ultrastructure and Affects the Sensitivity of Rice to High Temperature. Plants 2026, 15, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020284

Yang S, Li B, Qi P, Yin W, Xu L, Liu S, Wang C, Yang X, Gu X, Hu Y. CDE6 Regulates Chloroplast Ultrastructure and Affects the Sensitivity of Rice to High Temperature. Plants. 2026; 15(2):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020284

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shihong, Biluo Li, Pan Qi, Wuzhong Yin, Liang Xu, Siqi Liu, Chiyu Wang, Xiaoqing Yang, Xin Gu, and Yungao Hu. 2026. "CDE6 Regulates Chloroplast Ultrastructure and Affects the Sensitivity of Rice to High Temperature" Plants 15, no. 2: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020284

APA StyleYang, S., Li, B., Qi, P., Yin, W., Xu, L., Liu, S., Wang, C., Yang, X., Gu, X., & Hu, Y. (2026). CDE6 Regulates Chloroplast Ultrastructure and Affects the Sensitivity of Rice to High Temperature. Plants, 15(2), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020284