Systematic Analysis of the Maize CAD Gene Family and Identification of an Elite Drought-Tolerant Haplotype of ZmCAD6

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Stress Treatments

2.2. Identification and Chromosomal Distribution Analysis of ZmCAD Genes

2.3. Genomic Localization and Physicochemical Property Prediction of ZmCAD Genes

2.4. Analysis of Gene Structure, Conserved Domains, and Motifs of ZmCAD Genes

2.5. Prediction of Secondary, Tertiary Structures, and Subcellular Localization of ZmCAD Proteins

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis and Tissue Expression Profiles of ZmCAD Genes

2.7. Promoter Cis-Element Analysis and Transcription Factor Prediction

2.8. Cross-Species Ka/Ks and Collinearity Analysis of the ZmCAD Gene Family

2.9. Analysis of Evolutionary Selection Pressure and Functional Network of ZmCAD Genes

2.10. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.11. Natural Variation and Haplotype Diversity of ZmCAD6

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Properties and Chromosomal Distribution of the ZmCADs

| Protein | AA Count | MW (kDa) | pI | Instab. Index | Aliph. Index | GRAVY | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZmCAD1 | 432 | 47.26 | 8.62 | 37.65 | 81.67 | −0.17 | Mitochondrial |

| ZmCAD2 | 370 | 39.48 | 6.31 | 34.36 | 85.43 | −0.037 | Cytoplasm |

| ZmCAD3 | 361 | 38.71 | 6.82 | 27.51 | 92.33 | 0.048 | Cytoplasm |

| ZmCAD4 | 367 | 38.73 | 5.95 | 22.39 | 96.1 | 0.162 | Cytoplasm |

| ZmCAD5 | 365 | 37.96 | 5.52 | 26.44 | 88.08 | 0.152 | Cytoplasm |

| ZmCAD6 | 358 | 37.28 | 6.11 | 23.07 | 89.47 | 0.115 | Cytoplasm |

| ZmCAD7 | 414 | 43.46 | 7.19 | 32.1 | 86.62 | 0.028 | Cytoplasm |

| ZmCAD8 | 354 | 38.38 | 6.82 | 25.34 | 88.36 | −0.018 | Cytoplasm |

| ZmCAD9 | 359 | 38.00 | 6.45 | 29.57 | 86.38 | 0.061 | Cytoplasm |

3.2. Gene Structure and Protein Architecture of the ZmCADs

3.3. Secondary and Tertiary Structure Prediction of ZmCAD Proteins

3.4. Promoter Analysis of the ZmCAD Gene Family

3.5. Evolutionary Analysis of the ZmCAD Gene Family

3.6. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Analysis of ZmCADs

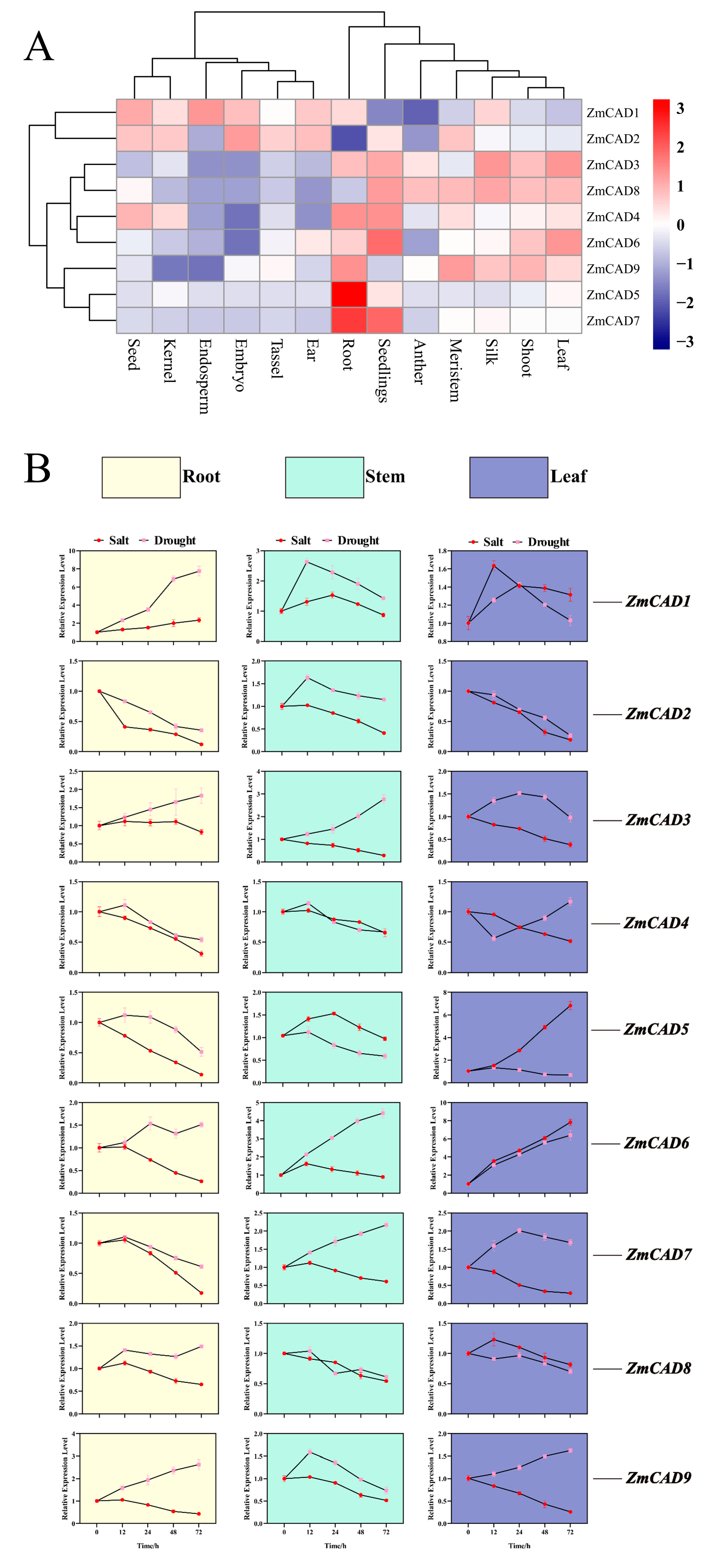

3.7. Tissue-Specific and Stress-Responsive Expression Profiles of ZmCADs

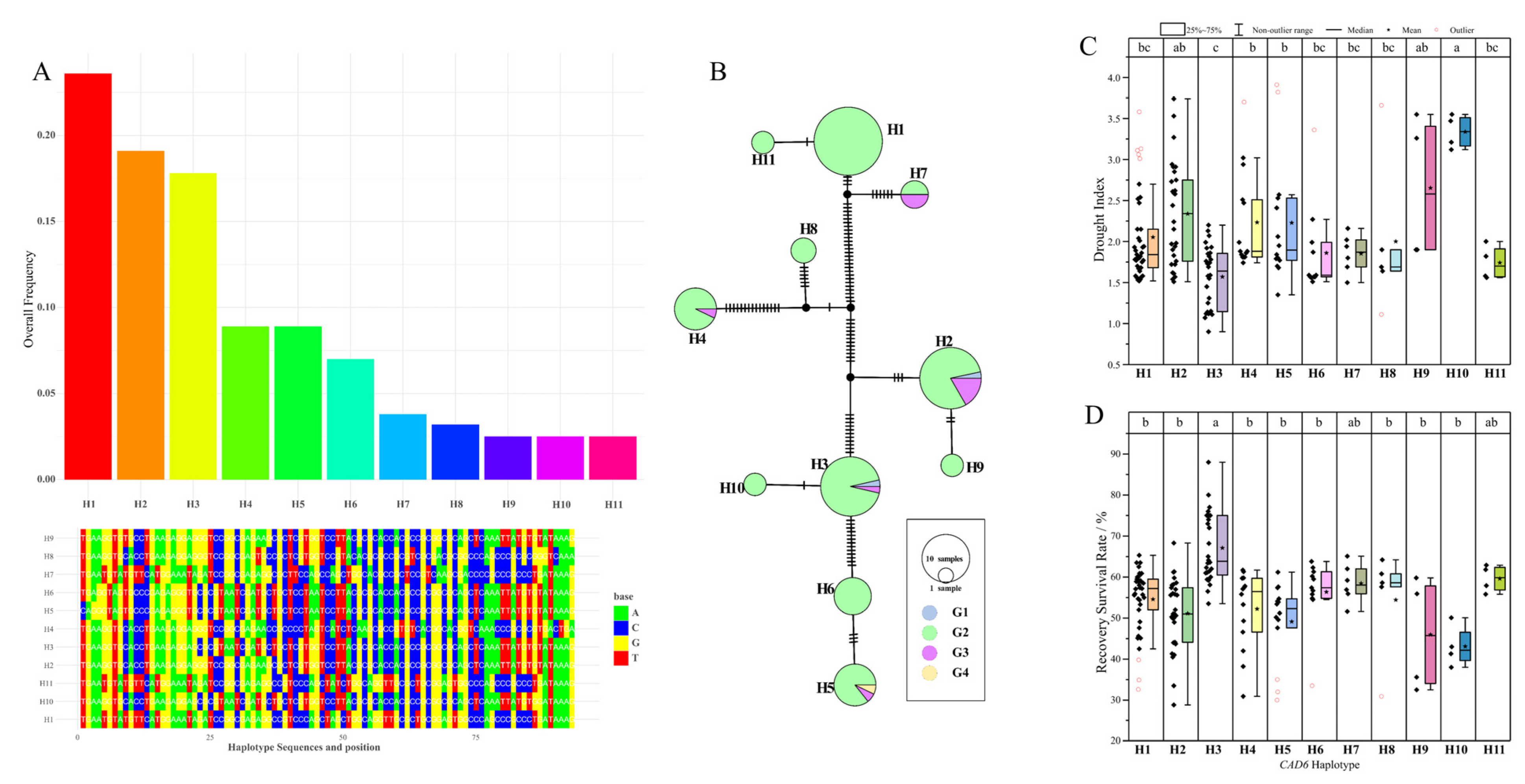

3.8. Identification of an Elite Drought-Tolerant Haplotype of ZmCAD6

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Jin, J.; Wang, S.; Du, B. Effects of irrigation water salinity on maize (Zea may L.) emergence, growth, yield, quality, and soil salt. Water 2019, 11, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Puccioni, S.; Eichmeier, A.; Storchi, P. Prevention of drought damage through zeolite treatments on Vitis vinifera: A promising sustainable solution for soil management. Soil Use Manag. 2024, 40, e13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, L.; Zheng, L.Q. Lignins: Biosynthesis and Biological Functions in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Chattopadhyay, D. Lignin: The Building Block of Defense Responses to Stress in Plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 6652–6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, P.; Jiang, Z.; Miao, M.; Wei, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Guan, S.; Ma, Y. Zmhdz9, an HD-zip transcription factor, promotes drought stress resistance in maize by modulating ABA and lignin accumulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, X.; Qin, F.; Jiang, C. A dirigent family protein confers variation of Casparian strip thickness and salt tolerance in maize. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholme, R.; De Meester, B.; Ralph, J.; Boerjan, W. Lignin biosynthesis and its integration into metabolism. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peracchi, L.M.; Brew-Appiah, R.A.; Garland-Campbell, K.; Roalson, E.H.; Sanguinet, K.A. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of the Cinnamyl Alcohol Dehydrogenase gene family in Triticum aestivum. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.L.; Kim, T.L.; Bhoo, S.H.; Lee, T.H.; Lee, S.W.; Cho, M.H. Biochemical characterization of the rice cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene family. Molecules 2018, 23, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saballos, A.; Ejeta, G.; Sanchez, E.; Kang, C.; Vermerris, W. A genomewide analysis of the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase family in sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) moench] identifies SbCAD2 as the brown midrib6 gene. Genetics 2009, 181, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Weng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tian, M.; Yang, Y.; Pan, N.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, H.; Du, H.; Yin, N.; et al. Identification of the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene family in brassica U-triangle species and its potential roles in response to abiotic stress and regulation of seed coat color in Brassica napus L. Plants 2025, 14, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Li, H.; Qu, M.; An, X.; Yang, J.; Fu, Y. Melatonin enhances salt tolerance by promoting CcCAD10-mediated lignin biosynthesis in pigeon pea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2025, 138, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walbot, V. 10 Reasons to be Tantalized by the B73 Maize Genome. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Qin, T.; Zheng, H.; Guan, Y.; Gu, W.; Wang, H.; Yu, D.; Qu, J.; Wei, J.; Xu, W. Mutation of ZmDIR5 reduces maize tolerance to waterlogging, salinity, and drought. Plants 2025, 14, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, H.; Xie, X.; Sun, B.; Liu, C. A quantitative index for evaluating maize leaf wilting and its sustainable application in drought resistance screening. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, L.; Hu, M.; Tian, H.; Hao, Y.; Ding, S.; Zhang, D. Comprehensive evaluation and screening of drought resistance in maize at germination and seedling stages. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1672228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, J.; Rohde, A.; Christensen, J.H.; Van de Peer, Y.; Boerjan, W. Genome-wide characterization of the lignification toolbox in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the ALDH gene family and functional analysis of PaALDH17 in Prunus avium. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.E.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker, J.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Anderson, J.B.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; DeWeese-Scott, C.; Fong, J.H.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; et al. CDD: Specific functional annotation with the conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D205–D210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geourjon, C.; Deléage, G. SOPMA: Significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus predic-tion from multiple alignments. Bioinformatics 1995, 11, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; De Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L.; Laiho, A.; Törönen, P.; Salgado, M. DALI shines a light on remote homologs: One hundred discoveries. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.C.; Shen, H.B. Cell-PLoc 2.0: An improved package of web-servers for predicting subcellular localization of proteins in various organisms. Nat. Sci. 2010, 2, 1090–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.-J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Long, Y.; Shu, Y.; Zhai, J. Plant Public RNA-seq Database: A comprehensive online database for expression analysis of ~45,000 plant public RNA-Seq libraries. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengarelli, D.A.; Zanor, M.I. Genome-wide characterization and analysis of the CCT motif family genes in soybean (Glycine max). Planta 2021, 253, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, S.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Luo, J.; Xu, X.; Yuan, J.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Yang, X.; Wu, S.; et al. ZEAMAP, a comprehensive database adapted to the maize multi-omics era. iScience 2020, 23, 101241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Wertheim, J.O.; Weaver, S.; Murrell, B.; Scheffler, K.; Kosakovsky Pond, S. Less Is More: An Adaptive Branch-Site Random Effects Model for Efficient De-tection of Episodic Diversifying Selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein–protein association networks and func-tional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Wei, J.; Wang, H.; Fang, Y.; Yin, S.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C. Natural variation and domestication selection of ZmPGP1 affects plant architecture and yield-related traits in maize. Genes 2019, 10, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tronchet, M.; Balagué, C.; Kroj, T.; Jouanin, L.; Roby, D. Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases-C and D, key enzymes in lignin biosynthesis, play an essential role in disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2010, 11, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, H.; Qian, X.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X.; Pang, J.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Dong, Y.; Liu, B. Overexpression of a cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase-coding gene, GsCAD1, from wild soy-bean enhances resistance to soybean mosaic virus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isah, T. Stress and defense responses in plant secondary metabolites production. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drought Index | Phenotypic Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Normal growth, fully expanded leaves, no wilting symptoms. |

| 1 | Several leaves partially rolled and yellowed; plant erect but leaves flaccid. |

| 2 | Majority of leaves rolled into a tubular shape but still turgid; plant begins to lean. |

| 3 | All leaves severely rolled into a needle-like shape; stems softened; plant is prostrate/lodged. |

| 4 | Plant near death; leaves and stems are desiccated and bleached, but with signs of life. |

| 5 | Plant completely dead and fully desiccated. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Xu, W.; Qin, T.; Qu, J.; Guan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Xue, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zheng, H. Systematic Analysis of the Maize CAD Gene Family and Identification of an Elite Drought-Tolerant Haplotype of ZmCAD6. Plants 2026, 15, 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020241

Zhao Z, Xu W, Qin T, Qu J, Guan Y, Hu Y, Xue W, Lu Y, Wang H, Zheng H. Systematic Analysis of the Maize CAD Gene Family and Identification of an Elite Drought-Tolerant Haplotype of ZmCAD6. Plants. 2026; 15(2):241. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020241

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhixiong, Wen Xu, Tao Qin, Jingtao Qu, Yuan Guan, Yingxiong Hu, Wenyu Xue, Yuan Lu, Hui Wang, and Hongjian Zheng. 2026. "Systematic Analysis of the Maize CAD Gene Family and Identification of an Elite Drought-Tolerant Haplotype of ZmCAD6" Plants 15, no. 2: 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020241

APA StyleZhao, Z., Xu, W., Qin, T., Qu, J., Guan, Y., Hu, Y., Xue, W., Lu, Y., Wang, H., & Zheng, H. (2026). Systematic Analysis of the Maize CAD Gene Family and Identification of an Elite Drought-Tolerant Haplotype of ZmCAD6. Plants, 15(2), 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020241