Interactive Effects of Root-Promoting Treatments and Media on Clonal Propagation of Two Western Pine Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Description

2.2. Studies

Donor Material

2.3. Design

2.4. Root-Promoting Treatments Description

2.5. Rooting Media Description

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

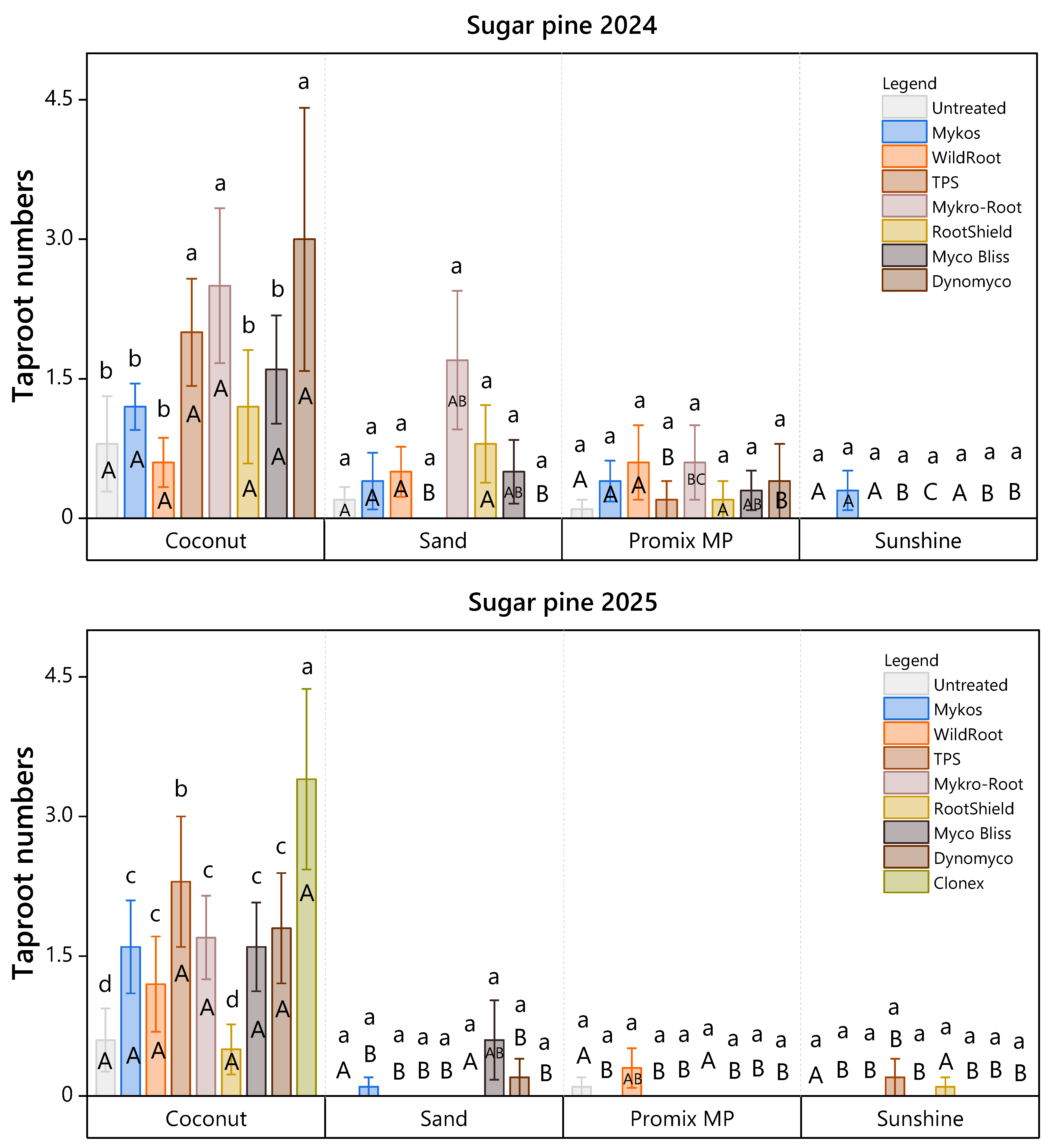

3.1. Studies in March 2024 and 2025

3.2. Study in January 2025

3.3. Effect Sizes for the Studies in March 2024 and 2025

4. Discussion

4.1. Studies in March 2024 and 2025

4.2. Study in January 2025

4.3. Effect Sizes for the Studies in March 2024 and 2025

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kinloch, B.B., Jr.; Scheuner, W.H.; Vogler, D.R. Pinus lambertiana Dougl. In Silvics of North America, Volume 1: Conifers; Burns, R.M., Honkala, B.H., Eds.; USDA Forest Service Agriculture Handbook 654; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 370–379. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, W.W.; Ryker, R.A. Ponderosa pine. In Silvics of North America, Volume 1: Conifers; United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 413–424. Available online: https://research.fs.usda.gov/silvics/ponderosa-pine (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Kinlock, B.B., Jr. Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana Dougl.): An American Wood; FS-257; United States Department of Agriculture, US Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; pp. 1–7. Available online: https://www.fpl.fs.usda.gov/documnts/usda/amwood/257sugpi.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Graham, R.T.; Jain, T.B. Ponderosa pine ecosystems. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Ponderosa Pine: Issues, Trends, and Management, Klamath Falls, OR, USA, 18–21 October 2004; Ritchie, M.W., Maguire, D.A., Youngblood, A., Eds.; Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-198; Coordinators. Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Albany, CA, USA, 2005; Volume 198, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Rumann, C.S.; Morgan, P. Tree regeneration following wildfires in the western US: A review. Fire Ecol. 2019, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargione, J.; Haase, D.L.; Burney, O.T.; Kildisheva, O.A.; Edge, G.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Chapman, T.; Rempel, A.; Hurteau, M.D.; Davis, K.T.; et al. Challenges to the reforestation pipeline in the United States. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 629198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens-Rumann, C.S.; Prichard, S.J.; Whitman, E.; Parisien, M.A.; Meddens, A.J. Considering regeneration failure in the context of changing climate and disturbance regimes in western North America. Can. J. For. Res. 2022, 52, 1281–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.T.; Robles, M.D.; Kemp, K.B.; Higuera, P.E.; Chapman, T.; Metlen, K.L.; Peeler, J.L.; Rodman, K.C.; Woolley, T.; Addington, R.N.; et al. Reduced fire severity offers near-term buffer to climate-driven declines in conifer resilience across the western United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2208120120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cansler, C.A.; Wright, M.C.; Van Mantgem, P.J.; Shearman, T.M.; Varner, J.M.; Hood, S.M. Drought before fire increases tree mortality after fire. Ecosphere 2024, 15, e70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.S.; Pinto, J.R. The scientific basis of the target plant concept: An overview. Forests 2021, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesselmann, A.K.V.; Richardson, S.J.; Bellingham, P.J.; Wright, E.; Jo, I.; Hawcroft, A.; Monks, A. Survival and environmental filtering of angiosperm and conifer seedlings at range-wide scales throughout temperate evergreen rainforests. J. Ecol. 2025, 113, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, S.N.; Yeaman, S.; Holliday, J.A.; Wang, T.; Curtis-McLane, S. Adaptation, migration or extirpation: Climate change outcomes for tree populations. Evol. Appl. 2008, 1, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S. Implementation of conifer somatic embryogenesis in clonal forestry: Technical requirements and deployment considerations. Ann. For. Sci. 2002, 59, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S. Clonal Forestry I: Genetics and biotechnology, Clonal Forestry II: Conservation and application. For. Sci. 1994, 40, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.X. Benefits and risks of using clones in forestry—A review. Scand. J. For. Res. 2019, 34, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.C.; Indu, K.; Bhargavi, C.; Rajendra, M.P.; Babu, B.H. A review on vegetative propagation and applications in forestry. J. Plant Dev. Sci. 2022, 14, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P.K. Somatic embryogenesis in sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana Dougl.). In Somatic Embryogenesis in Woody Plants; Forestry Sciences; Jain, S.M., Gupta, P.K., Newton, R.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; Volumes 44–46, pp. 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Durzan, D. Somatic Polyembryogenesis from callus of mature sugar pine embryos. Nat. Biotechnol. 1986, 4, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Vargas, A.; Castander-Olarieta, A.; do Nascimento, A.M.M.; Vélez, M.L.; Pereira, C.; Martins, J.; Zuzarte, M.; Canhoto, J.; Montalbán, I.A.; Moncaleán, P. Testing explant sources, culture media, and light conditions for the improvement of organogenesis in Pinus ponderosa (P. Lawson and C. Lawson). Plants 2023, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Chen, X.-L.; Hao, Y.-P.; Jiang, C.-W.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, Q.; Chen, S.-J.; Yu, X.-S.; Cheng, F.; et al. Optimization of factors affecting the rooting of pine wilt disease resistant masson pine (Pinus massoniana) stem cuttings. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.G.; Zwolinski, J.; Jones, N.B. A review on the effects of donor maturation on rooting and field performance of conifer cuttings. S. Afr. For. J. 2004, 2004, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragonezi, C.; Klimaszewska, K.; Castro, M.R.; Lima, M.; Oliveira, P.; Zavattieri, M.A. Adventitious rooting of conifers: Influence of physical and chemical factors. Trees 2010, 24, 975–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, D.; Amaranthus, M.P.; Cazares, E. Survival of ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa Dougl. ex LAWS.) seedlings outplanted with Rhizopogon mycorrhizae inoculated with spores at the nursery. J. Arboric. 2003, 29, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, B.N.; Sharma, G.D.; Shukla, A.K. Ectomycorrhizal development and pine seedlings growth in response to different physical factors. Acta Bot. Hung. 2007, 49, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, K.; Vuorinen, T.; Ernstsen, A. Ectomycorrhizal fungi and exogenous auxins influence root and mycorrhiza formation of Scots pine hypocotyl cuttings in vitro. Tree Physiol. 2002, 22, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, K.; Scagel, C.F.; Häggman, H. Application of ectomycorrhizal fungi in vegetative propagation of conifers. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2004, 78, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, L.; Bartschi, H.; Debaud, J. Rooting and acclimatization of micropropagated cuttings of Pinus pinaster and Pinus sylvestris are enhanced by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Hebeloma cylindrosporum. Physiol. Plant. 1996, 98, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 273–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro Júnior, J.I.; Melo, A.L.P. Guia Prático para Utilização do SAEG; Folha Artes Gráficas Ltda: Viçosa, Brasil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- OriginPro, Version 2025; OriginLab Corporation: Northampton, MA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.originlab.com/origin (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Browne, R.D.; Davidson, C.G.; Steeves, T.A.; Dunstan, D.I. Rooting of proliferated dwarf shoot cuttings of jack pine (Pinus banksiana). Can. J. For. Res. 1997, 27, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosier, C.L.; Frampton, J.; Goldfarb, B.; Blazich, F.A.; Wise, F.C. Growth stage, auxin type, and concentration influence rooting of stem cuttings of Fraser fir. HortScience 2004, 39, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witcher, A.L.; Blythe, E.K.; Fain, G.B.; Curry, K.J. Stem cutting propagation in whole pine tree substrates. HortTechnology 2014, 24, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.; Stelzer, H.; McRae, J. Loblolly pine cutting morphological traits: Effects on rooting and field performance. New For. 2000, 19, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struve, D.K.; McKeand, S.E. Growth and development of eastern white pine rooted cuttings compared with seedlings through 8 years of age. Can. J. For. Res. 1990, 20, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, W.J.; Brown, A.G.; Fielding, J.M. Effects of hedging radiata pine on production, rooting, and early growth of cuttings. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 1972, 2, 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, M.S.; Cui, X.; Xu, F. Response to auxin changes during maturation-related loss of adventitious rooting competence in loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) stem cuttings. Physiol. Plant. 2001, 111, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, L.J.; Hodges, J.F. Nursery rooting of cuttings from seedlings of Slash and Loblolly Pine. South. J. Appl. For. 1989, 13, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebude, A.V.; Goldfarb, B.; Blazich, F.A.; Wise, F.C.; Frampton, J. Mist, substrate water potential and cutting water potential influence rooting of stem cuttings of loblolly pine. Tree Physiol. 2004, 24, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scagel, C.; Reddy, K.; Armstrong, J. Mycorrhizal Fungi in Rooting Substrate Influences the Quantity and Quality of Roots on Stem Cuttings of Hick’s Yew. HortTechnology 2003, 13, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scagel, C. Enhanced rooting of kinnikinnick cuttings using mycorrhizal fungi in rooting substrate. HortTechnology 2004, 14, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Filho, J.B. (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Riverside, CA, USA). Personal communication, 2024.

- Garcia, M.O.; Smith, J.E.; Luoma, D.L.; Jones, M.D. Ectomycorrhizal communities of ponderosa pine and lodgepole pine in the south-central Oregon pumice zone. Mycorrhiza 2016, 26, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.; Nam, S.Y. Optimized concentrations of auxinic rooting promoters improve stem cutting propagation efficiency and morphophysiological characteristics in Hedera algeriensis cv. Gloire de Marengo. Hortic. Sci. Technol 2025, 43, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiang, Y.T.; Rogers, O.M.; Pike, R.B. Vegetative propagation of Eastern white pine by cuttings. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 1974, 4, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Parladé, J.; Pera, J.; Álvarez, I.F.; Bouchard, D.; Généré, B.; Le Tacon, F. Effect of inoculation and substrate disinfection method on rooting and ectomycorrhiza formation of Douglas fir cuttings. Ann. For. Sci. 1999, 56, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavattieri, M.A.; Ragonezi, C.; Klimaszewska, K. Adventitious rooting of conifers: Influence of biological factors. Trees 2016, 30, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Tailor, A.; Gogna, M.; Bhushan, B.; Aggarwal, S.K.; Mehta, S. Wound response and primary metabolism during adventitious root formation in cuttings. In Environmental, Physiological, and Chemical Controls of Adventitious Rooting in Cuttings; Husen, A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 65–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.R.; Aumond, M.; Costa, C.T.; Schwambach, J.; Ruedell, C.M.; Correa, L.R.; Fett-Neto, A.G. Environmental control of adventitious rooting in eucalyptus and populus cuttings. Trees 2017, 31, 1377–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Xie, J.; Wang, X.; Gu, H.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Yang, X. Research status and prospects on the construction methods of temperature and humidity environmental models in arbor tree cuttage. Agronomy 2024, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar-Hill, Y.; Pfeffer, P.E.; Douds, D.D.; Osman, S.F.; Doner, L.W.; Ratcliffe, R.G. Partitioning of carbon in arbuscular mycorrhizas: A 13C NMR study. Plant Physiol. 1995, 108, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehls, U.; Grunze, N.; Willmann, M.; Reich, M.; Küster, H. Sugar for my honey: Carbohydrate partitioning in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Shen, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, T.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, W.; Cheng, R. Photosynthetic product allocations of Pinus massoniana seedlings inoculated with ectomycorrhizal fungi along a nitrogen addition gradient. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 965582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Yu, B.; Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; Deng, B. Mycorrhizal fungi synergistically promote the growth and secondary metabolism of Cyclocarya paliurus. Forests 2022, 13, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.R.; Konduru, S.; Stamps, R.H. Source variation in physical and chemical properties of coconut coir dust. HortScience 1996, 31, 965–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckeldoe, R.B.; Maluleke, M.K.; Adriaanse, P. The effect of coconut coir substrate on the yield and nutritional quality of sweet peppers (Capsicum annuum) varieties. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 29914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Niu, T.; Lian, W.; Ye, T.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J. Involvement of endogenous IAA and ABA in the regulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on rooting of tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.) cuttings. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shan, W.; Niu, T.; Ye, T.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J. Insight into regulation of adventitious root formation by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and exogenous auxin in tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.) cuttings. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1258410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampp, R.; Schaeffer, C. Mycorrhiza—Carbohydrate and energy metabolism. In Mycorrhiza; Varma, A., Hock, B., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, E. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on rooting ability of auxin treated stem cuttings of Dalbergia melanoxylon (Guill and Perr.). Res. J. Bot. 2015, 10, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, F.C.; Caldwell, T.D. Macropropagation of conifers by stem cuttings. In Proceedings of the Southern Regional Information Exchange Group Biennial Symposium on Forest Genetics: Applications of Vegetative Propagation in Forestry; Foster, G.S., Diner, A.M., Eds.; Southern Forest Experiment Station: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1994; pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, H.; Wu, H.; Shen, W.; Lin, J.; Zhao, Y. Seasonal changes in cambium activity from active to dormant stage affect the formation of secondary xylem in Pinus tabulaeformis. Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijidani, Y.; Tsuyama, T.; Takata, K. Seasonal variations of auxin and gibberellin A4 levels in cambial-region tissues of three conifers. J. Wood Sci. 2021, 67, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.L.; Holeski, L.M.; Lindroth, R.L. Independent and interactive effects of plant genotype and environment on plant traits and insect herbivore performance: A meta-analysis with Salicaceae. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.T.; Kester, D.E.; Davies, F.T., Jr.; Geneve, R.L. Hartmann and Kester’s Plant Propagation: Principles and Practices, 8th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2011; 928p. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S.M.; Anderson, S.L.; Brym, Z.T.; Pearson, B.J. Evaluation of substrate composition and exogenous hormone application on vegetative propagule rooting success of essential oil hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, G.A. The commercial use of conifer rooted cuttings in forestry: A world overview. New For. 1991, 5, 247–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Müller, J.; Vertocnik, A.; Town, C.D. Analysis of indole-3-butyric acid-induced adventitious root formation on Arabidopsis stem segments. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 2095–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Main Species/Strains | Concentration/Propagules | Additional Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mykos 1 | Rhizophagus intraradices | 300 propagules g−1 | – |

| Wildroot 2 | Nine endomycorrhizal species: | – | |

| Glomus intraradices | 69 propagules g−1 | ||

| Glomus mosseae | 69 propagules g−1 | ||

| Glomus aggregatum | 69 propagules g−1 | ||

| Glomus etunicatum | 69 propagules g−1 | ||

| Glomus monosporum | 34 propagules g−1 | ||

| Glomus deserticula | 34 propagules g−1 | ||

| Glomus clarum | 34 propagules g−1 | ||

| Paraglomus brasilianum | 34 propagules g−1 | ||

| Gigaspora margarita | 34 propagules g−1 | ||

| Seven ectomycorrhizal species: | |||

| Rhizopogon villosulus | 16,500 propagules g−1 | ||

| Rhizopogon luteolus | 16,500 propagules g−1 | ||

| Rhizopogon amylopogon | 16,500 propagules g−1 | ||

| Rhizopogon fulvigleba | 16,500 propagules g−1 | ||

| Pisolithus tinctorius | 220,000 propagules g−1 | ||

| Scleroderma cepa | 11,000 propagules g−1 | ||

| Scleroderma citrinum | 11,000 propagules g−1 | ||

| TPS 3 | Four endomycorrhiza species: | 4–6 colony-forming units g−1 each | Bacillus spp. (5 species) and Trichoderma harzianum |

| Glomus intraradices | |||

| Glomus mosseae | |||

| Glomus aggregatum | |||

| Glomus etunicatum | |||

| Mykro-root 4 | Trichoderma harzianum, Trichoderma viride | 2 × 107 colony-forming units g−1 | Micronutrients (Zn, Cu, Mn, Mg, and Fe) |

| Rootshield Plus WP 5 | Trichoderma harzianum | 1.15% | – |

| Trichoderma virens strain G-41 | 0.61% | ||

| Myco Bliss 6 | Four ectomycorrhiza species: | 35 propagules g−1 each | – |

| Rhizophagus irregularis | |||

| Rhizophagus aggregatus | |||

| Rhizophagus proliferum | |||

| Rhizophagus clarus | |||

| and Claroideoglomus | |||

| etunicatum | |||

| Dynomyco 7 | Glomus intraradices | 700 propagules g−1 | – |

| Glomus mosseae | 200 propagules g−1 | ||

| Clonex (2025 only) 8 | IBA (Indole-3-butyric acid) | 0.31% | Rooting gel formulation |

| Rooting Media | Composition | Mycorrhizal Inoculation | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut coir 1 | Processed coir fiber | None | High water-holding capacity, good aeration |

| All-purpose Sand 2 | Coarse processed sand (washed) | None | High drainage, low nutrient retention |

| Pro Mix MP 3 | sphagnum peat moss (60–70% by volume), coir, perlite, limestone, and wetting agent | Glomus intraradices (1 viable spore g−1) | Enhanced nutrient uptake, organic formulation |

| Sunshine Mix #4 4 | Canadian sphagnum peat moss, coarse perlite, coir pith (coir), gypsum, dolomitic limestone, wood biochar, and wetting agent | Endomycorrhiza strains included | Balanced moisture retention and aeration |

| Factors | 2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|

| Sugar pine | ||

| Root-promoting treatment | 0.058 | 0.063 |

| Media | 0.427 | 0.528 |

| Interaction | 0.174 | 0.158 |

| Ponderosa pine | ||

| Root-promoting treatment | 0.103 | 0.141 |

| Media | 0.252 | 0.455 |

| Interaction | 0.133 | 0.202 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silva Filho, J.B.; Ferreira, A.R.; McGiffen, M.E., Jr. Interactive Effects of Root-Promoting Treatments and Media on Clonal Propagation of Two Western Pine Species. Plants 2026, 15, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020237

Silva Filho JB, Ferreira AR, McGiffen ME Jr. Interactive Effects of Root-Promoting Treatments and Media on Clonal Propagation of Two Western Pine Species. Plants. 2026; 15(2):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020237

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva Filho, Jaime Barros, Arnaldo R. Ferreira, and Milton E. McGiffen, Jr. 2026. "Interactive Effects of Root-Promoting Treatments and Media on Clonal Propagation of Two Western Pine Species" Plants 15, no. 2: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020237

APA StyleSilva Filho, J. B., Ferreira, A. R., & McGiffen, M. E., Jr. (2026). Interactive Effects of Root-Promoting Treatments and Media on Clonal Propagation of Two Western Pine Species. Plants, 15(2), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020237