Induction and Regeneration of Microspore-Derived Embryos for Doubled Haploid Production in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

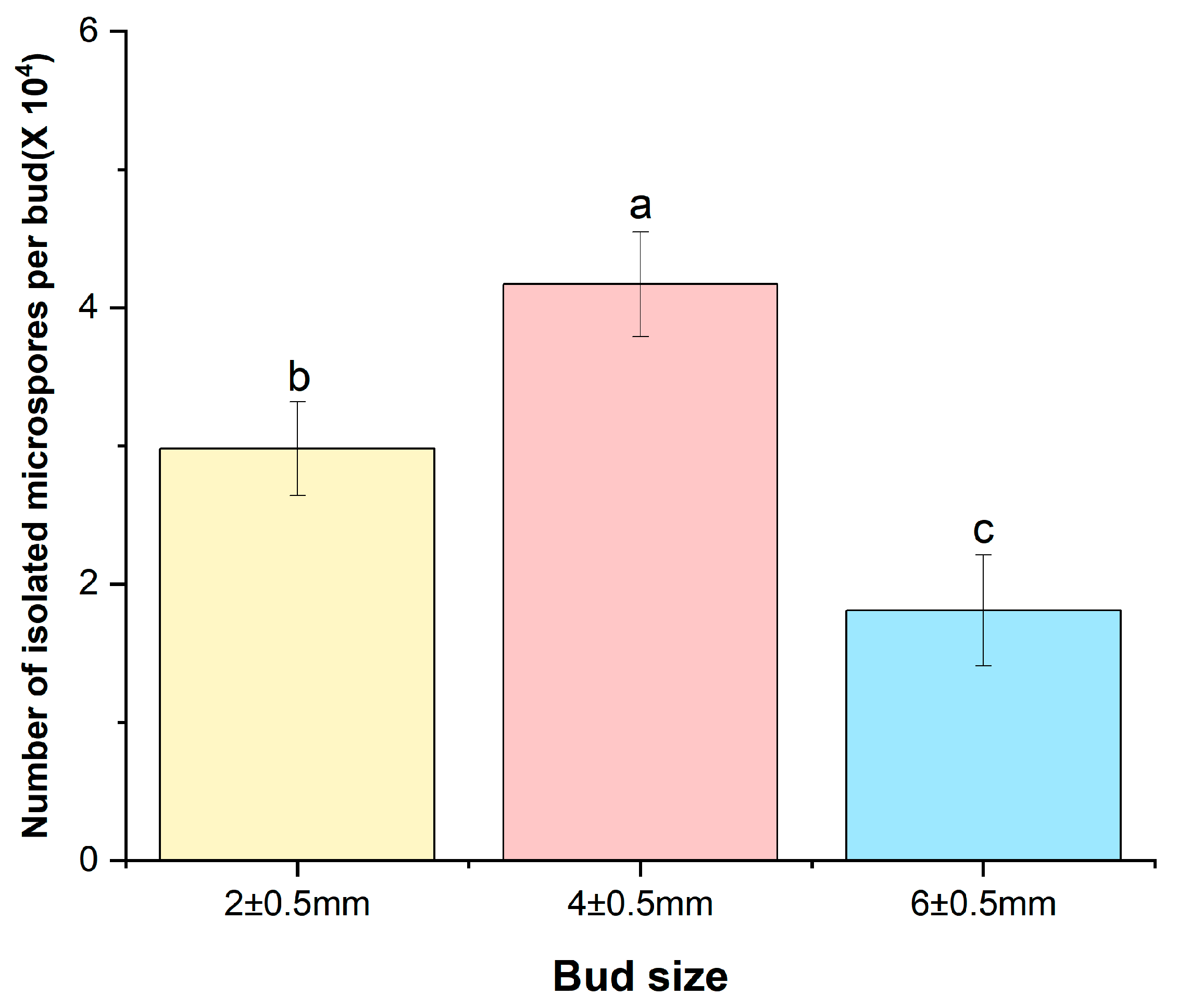

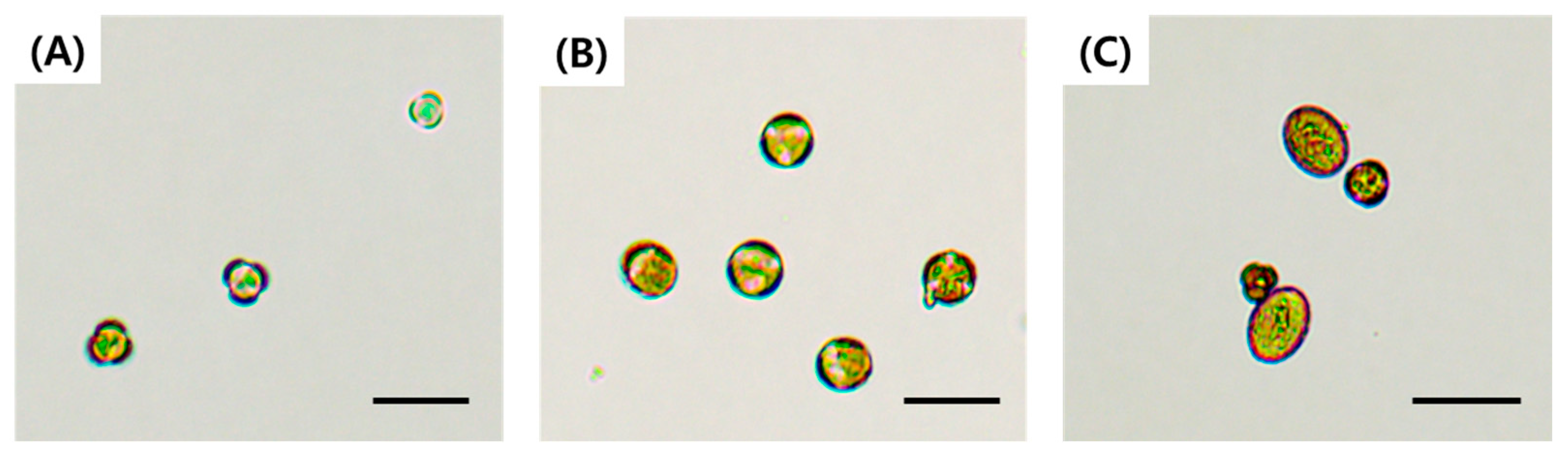

2.1. Microspore Yield, Development Stage, and Embryogenesis in Relation to Bud Size

2.2. Embryogenesis in Relation to Heat Shock Duration

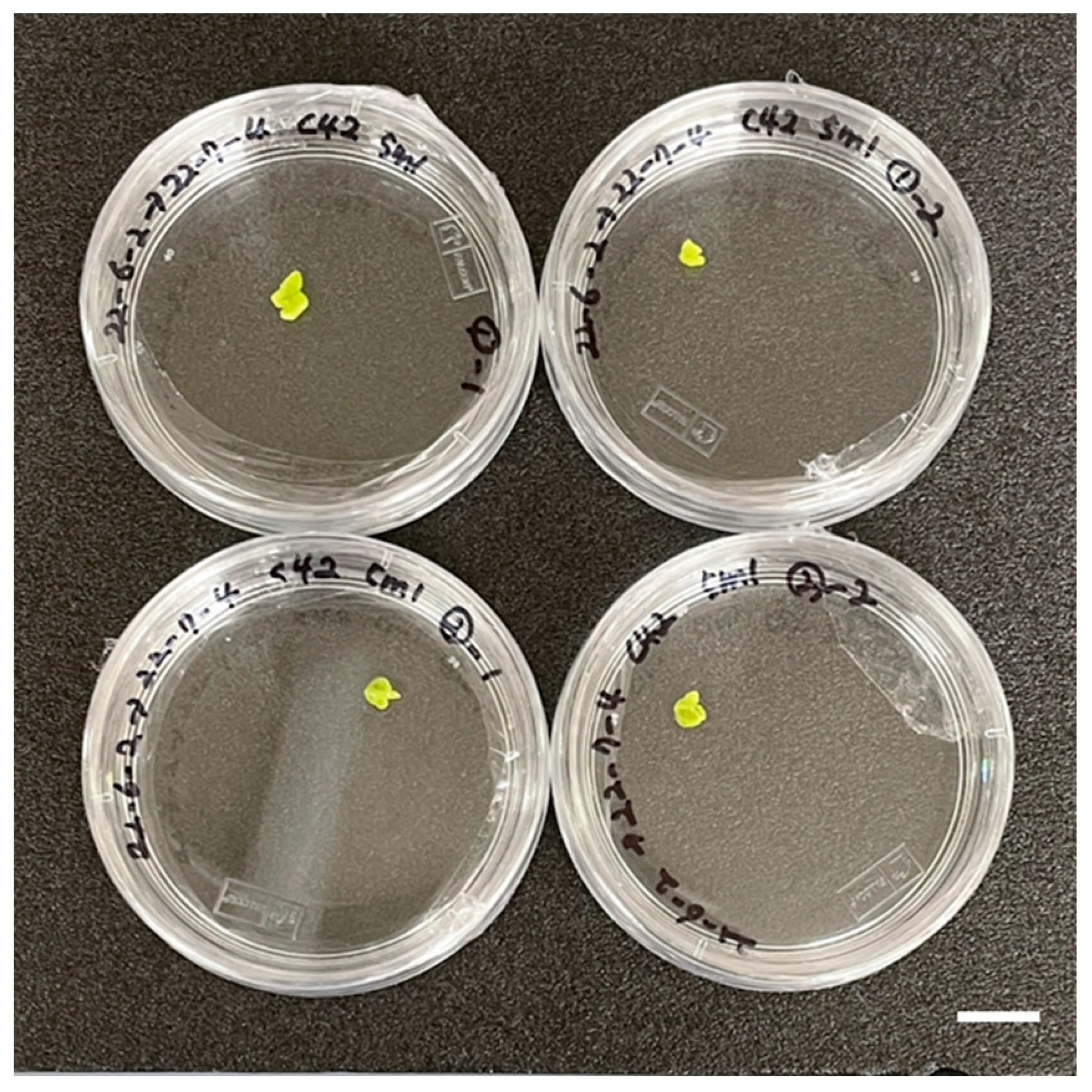

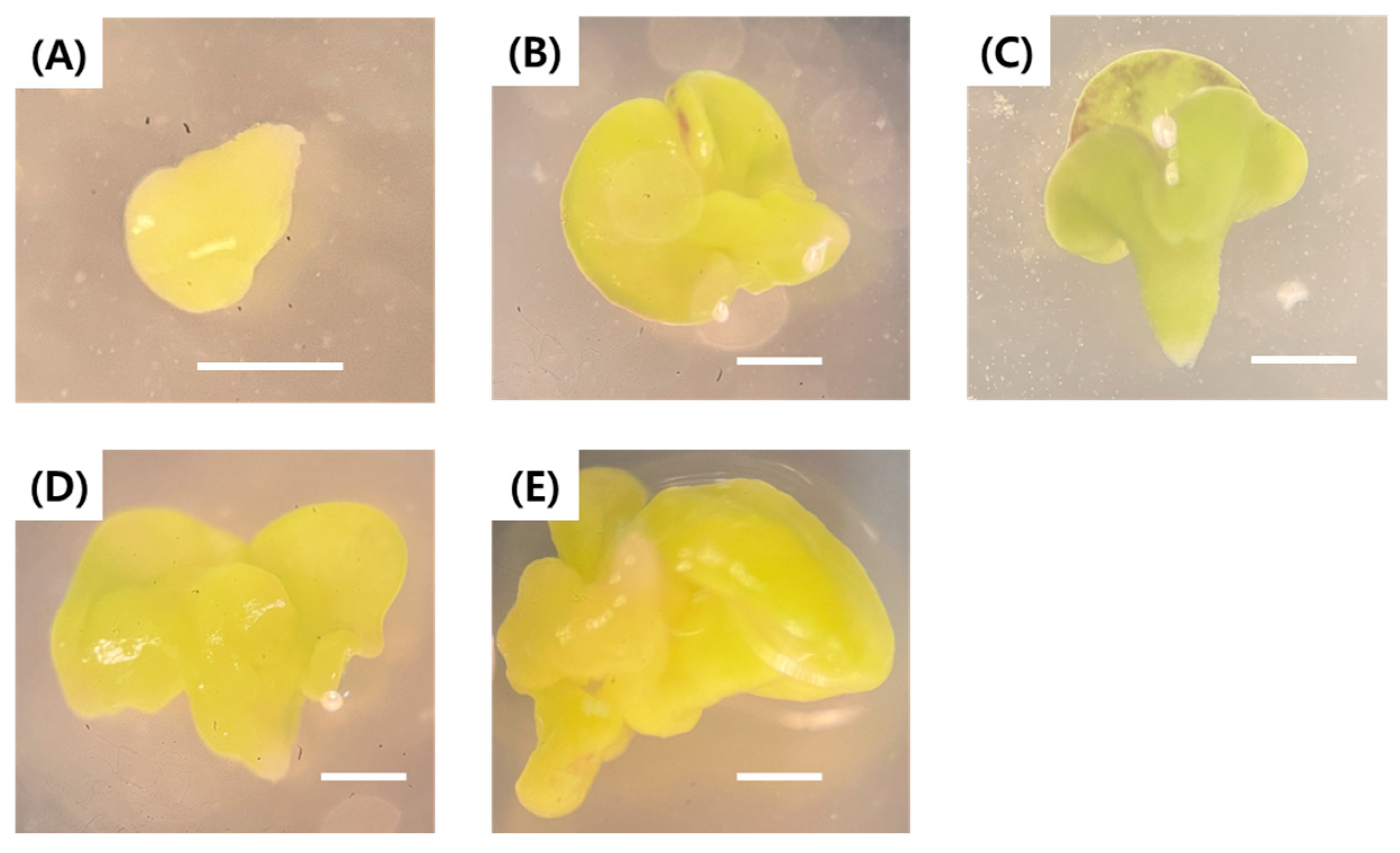

2.3. Regeneration in Relation to MS Salt Strength and Agar Concentration of Medium

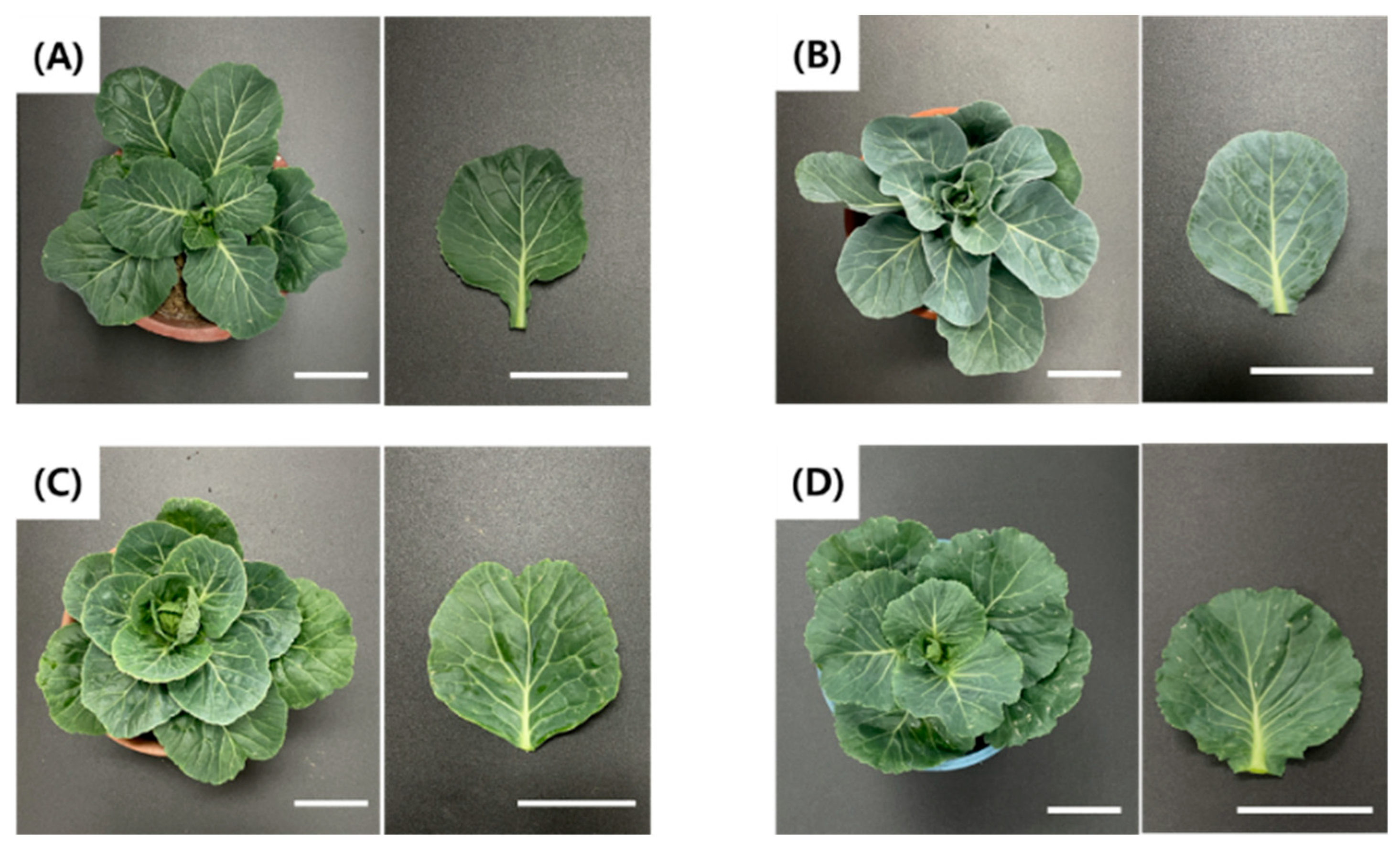

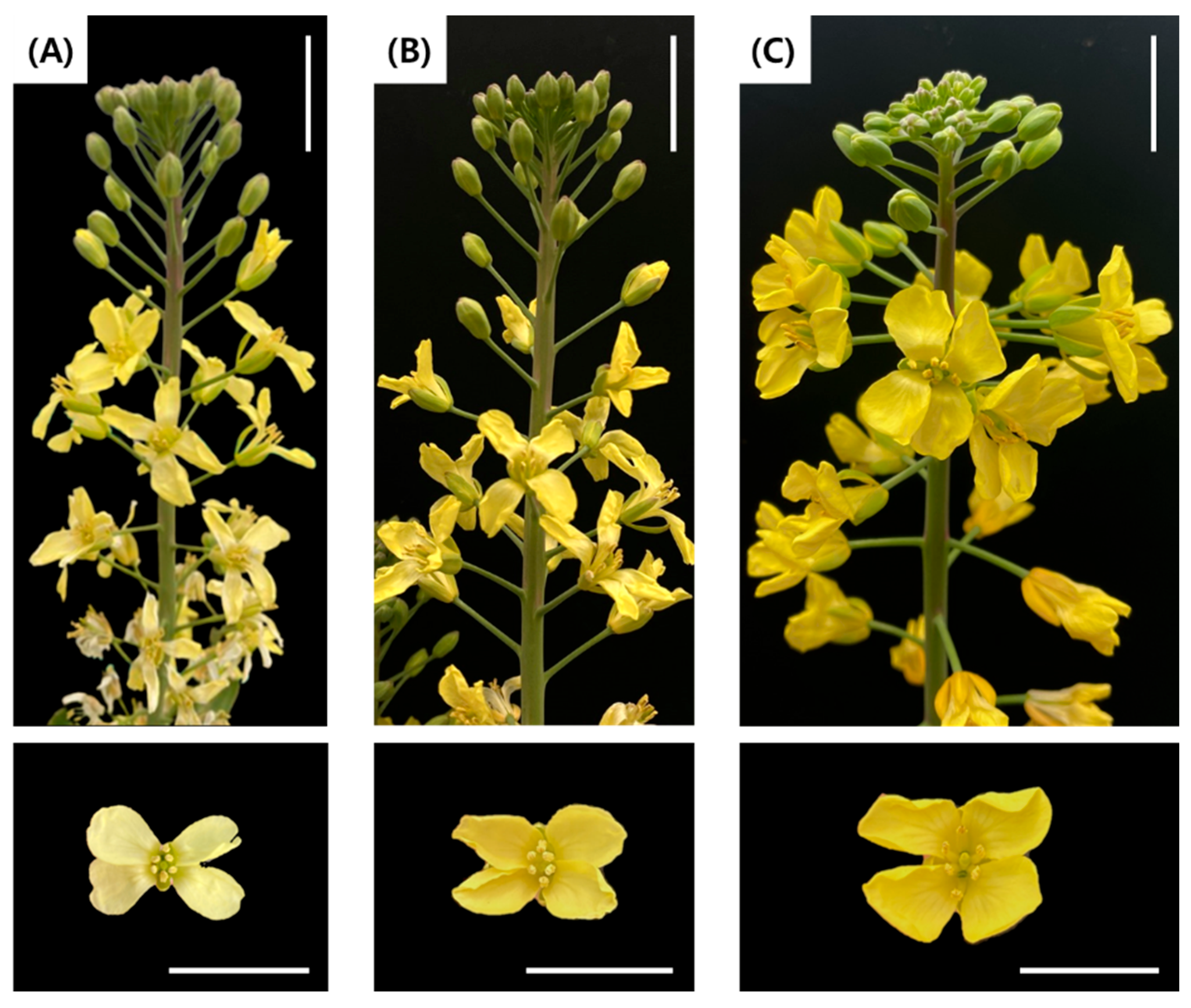

2.4. Acclimatization

2.5. Ploidy Level Determination of Regenerated Plants

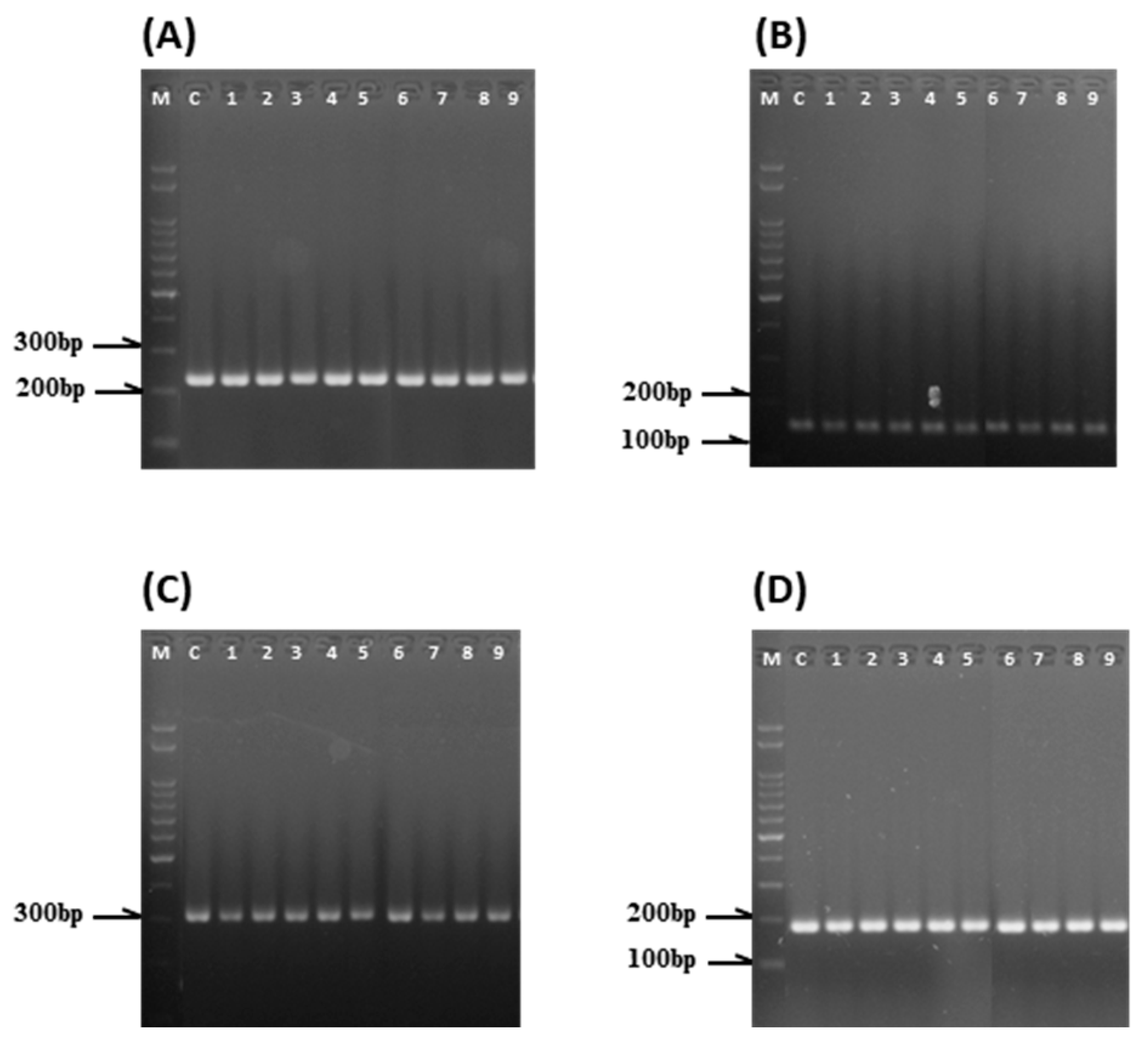

2.6. SSR Marker Analysis of Regenerated Plants

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Donor Plant Growth

4.2. Microspore Isolation and Culture

4.3. Plant Regeneration

4.4. Acclimatization

4.5. Ploidy Level Determination

4.6. SSR Marker Analysis of Regenerated Plants from Microspore-Derived Embryos

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delgado-Vargas, F.; Jiménez, A.; Paredes-López, O. Natural pigments: Carotenoids, anthocyanins, and betalains—Characteristics, biosynthesis, processing, and stability. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2000, 40, 173–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.-S.; Hong, E.-Y.; Kim, G.-H. Determination of bioactive compounds and anti-cancer effect from extracts of Korean cabbage and cabbage. Korean J. Food Nutr. 2012, 25, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KOSIS. Vegetable Production (Leafy Vegetables). Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1ET0028&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Dong, S.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Y. Low-toxicity herbicide dicamba promotes microspore embryogenesis and plant regeneration for doubled haploid production in purple cauliflower. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 336, 113405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrie, A.; Caswell, K. Isolated microspore culture techniques and recent progress for haploid and doubled haploid plant production. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2011, 104, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, R. Induction of haploid plants from isolated pollen of Brassica napus. Z. Pflanzenphysiol. 1982, 105, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechan, P.; Keller, W. Identification of potentially embryogenic microspores in Brassica napus. Physiol. Plant. 1988, 74, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, W.; Li, J.; Qi, X.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Y. Effects of genotype and sodium p-nitrophenolate on microspore embryogenesis and plant regeneration in broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica). Sci. Hortic. 2022, 293, 110711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zou, X.; Gong, Z.; Song, G.; Ren, J.; Feng, H. Thidiazuron promoted microspore embryogenesis and plant regeneration in curly kale (Brassica oleracea L. convar. acephala var. sabellica). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Z.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Y. Successful application of microspore culture in pakchoi (Brassica campestris L. ssp. chinensis Makino var. communis Tsen et Lee) for hybrid breeding. Protoplasma 2023, 260, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Doré, C. Embryogenesis and plant regeneration of pakchoi (Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis) via in vitro isolated microspore culture. Plant Cell Rep. 1994, 13, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, B.; Yanmaz, R. Effects of colchicine and high temperature treatments on isolated microspore culture in various cabbage (Brassica oleraceae) types. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2011, 13, 819–822. [Google Scholar]

- Cristea, T.; Ambarus, S.; Calin, M.; Brezeanu, C.; Brezeanu, P. White cabbage microspore response to low temperature treatment as a trigger for embryogenesis. In Proceedings of the International Horticultural Congress IHC2018: II International Symposium on Micropropagation and In Vitro Techniques 1285, Istanbul, Turkey, 12–16 August 2018; pp. 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.Y.; Jang, H.-Y.; Lim, Y.P.; Lee, J.-S.; Park, S. Influence of culture duration and conditions on embryogenesis of isolated microspore culture in cabbage (Brassica oleraceae L. var. capitata). J. Plant Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, P.; Moieni, A.; Karimzadeh, G.; Abdollahi, M. Effects of gibberellin, abscisic acid and embryo desiccation on normal plantlet regeneration, secondary embryogenesis and callogenesis in microspore culture of Brassica napus L. cv. PF704. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2008, 2, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, P. Plant regeneration from microspore-derived embryos in cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. Capitata) and Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. Italica). Chin. Bull. Bot. 2010, 45, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineykina, A.; Stebnitskaia, K.; Fomicheva, M.; Bondareva, L.; Domblides, A.; Domblides, E. Optimization of technology steps for obtaining white cabbage DH-plants. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2025, 29, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahira, J.; Cousin, A.; Nelson, M.; Cowling, W. Improvement in efficiency of microspore culture to produce doubled haploid canola (Brassica napus L.) by flow cytometry. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2011, 104, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kron, P.; Loureiro, J.; Castro, S.; Čertner, M. Flow cytometric analysis of pollen and spores: An overview of applications and methodology. Cytom. Part A 2021, 99, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, R.; Sharma, K.; Parkash, C.; Pramanik, A.; Singh, D.; Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Dey, S. Microspore derived population developed from an inter-specific hybrid (Brassica oleracea × B. carinata) through a modified protocol provides insight into B genome derived black rot resistance and inter-genomic interaction. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2021, 145, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Su, X.; Zhai, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L. Effects of genotype and culture conditions on microspore embryogenesis in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Mol. Breed. 2022, 42, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, R.; Chaturvedi, R. In vitro production of doubled haploid plants in Camellia spp. and assessment of homozygosity using microsatellite markers. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 361, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, W.-P.; Jia, Y.-Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Lou, Q.-F.; Chen, J.-F. Efficient embryo induction in cucumber ovary culture and homozygous identification of the regenetants using SSR markers. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 119, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.S.; Min, K.; Oh, Y.; Chung, D. Comparisons of developmental stages of microspore by bud size and embryogenesis from its microspore in Brassica species. Korean J. Breed. 1997, 29, 480–485. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, R.; Dey, S.; Parkash, C.; Sharma, K.; Sood, S.; Kumar, R. Modification of important factors for efficient microspore embryogenesis and doubled haploid production in field grown white cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata L.) genotypes in India. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 233, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R.; Dey, S.; Sood, S.; Sharma, K.; Sharma, V.; Parkash, C.; Kumar, R. Optimizing protocol for efficient microspore embryogenesis and doubled haploid development in different maturity groups of cauliflower (B. oleracea var. botrytis L.) in India. Euphytica 2016, 212, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraha, E.; Bechyn, M.; Klima, M.; Vyvadilova, M. Analysis of factors affecting embryogenesis in microspore cultures of Brassica carinata. Agric. Trop. Subtrop. 2008, 41, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Narae, H.; Un, K.S.; Young, P.H.; Haeyoung, N. Microspore-derived embryo formation and morphological changes during the isolated microspore culture of radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2014, 32, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kwak, J.-H.; Do, K.R.; Na, H. Developmental Stage and Density of Microspore by Flower Structure in Broccoli Lines. Korean J. Breed. Sci. 2013, 45, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.L. Pollen embryogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testillano, P.S. Microspore embryogenesis: Targeting the determinant factors of stress-induced cell reprogramming for crop improvement. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 2965–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordewener, J.H.; Hause, G.; Görgen, E.; Busink, R.; Hause, B.; Dons, H.J.; Van Lammeren, A.A.; Van Lookeren Campagne, M.M.; Pechan, P. Changes in synthesis and localization of members of the 70-kDa class of heat-shock proteins accompany the induction of embryogenesis in Brassica napus L. microspores. Planta 1995, 196, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Chen, G.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lv, H. Proteomic variations after short-term heat shock treatment reveal differentially expressed proteins involved in early microspore embryogenesis in cabbage (Brassica oleracea). PeerJ 2020, 8, e8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahata, Y.; Keller, W.A. High frequency embryogenesis and plant regeneration in isolated microspore culture of Brassica oleracea L. Plant Sci. 1991, 74, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Dias, J.C. Effect of incubation temperature regimes and culture medium on broccoli microspore culture embryogenesis. Euphytica 2001, 119, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, E.; Moysset, L.; Trillas, M. Effects of agar concentration and vessel closure on the organogenesis and hyperhydricity of adventitious carnation shoots. Biol. Plant. 2008, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Yokoi, S.; Takahata, Y. Improvement of microspore culture method for multiple samples in Brassica. Breed. Sci. 2011, 61, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S. Effects of the matric potential of culture medium on plant regeneration of embryo derived from microspore of Brassica napus. J. SHITA 1994, 5, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siong, P.K.; Taha, R.M.; Rahiman, F.A. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration from hypocotyl and leaf explants of Brassica oleracea var. botrytis (cauliflower). Acta Biol. Cracoviensia Ser. Bot. 2011, 53, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, M.; Roy, P.; Kabir, M.; Ahmed, G. In vitro regeneration of cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata) through hypocotyl and cotyledon culture. Plant Tissue Cult. Biotechnol. 2007, 17, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.; Kwak, J.-H.; Chun, C. The effects of plant growth regulators, activated charcoal, and AgNO3 on microspore derived embryo formation in broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica). Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2011, 52, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuginuki, Y.; Miyajima, T.; Masuda, H.; Hida, K.-i.; Hirai, M. Highly regenerative cultivars in microspore culture in Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata. Breed. Sci. 1999, 49, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Shi, X.; Fu, Q.; Bao, M. Improvement of isolated microspore culture of ornamental kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala): Effects of sucrose concentration, medium replacement, and cold pre-treatment. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommert, P.; Werr, W. Gene expression patterns in the maize caryopsis: Clues to decisions in embryo and endosperm development. Gene 2001, 271, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabelli, P.A. Seed development: A comparative overview on biology of morphology, physiology, and biochemistry between monocot and dicot plants. In Seed Development: OMICS Technologies Toward Improvement of Seed Quality and Crop Yield; OMICS in Seed Biology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineykina, A.; Bondareva, L.; Soldatenko, A.; Domblides, E. Androgenesis of red cabbage in isolated microspore culture in vitro. Plants 2021, 10, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smykalova, I.; Vetrovcova, M.; Klíma, M.; Machackova, I.; Griga, M. Efficiency of microspore culture for doubled haploid production in the breeding project” czech winter rape”. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2006, 42, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, M.; Li, H.; Boutilier, K. Microspore embryogenesis: Establishment of embryo identity and pattern in culture. Plant Reprod. 2013, 26, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos, C.; Gémes Juhász, A.; Vági, P.; Mihály, R.; Kristóf, Z.; Pauk, J. Androgenesis induction in microspore culture of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2012, 6, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrie, A.; Irmen, K.; Beattie, A.; Rossnagel, B. Isolated microspore culture of oat (Avena sativa L.) for the production of doubled haploids: Effect of pre-culture and post-culture conditions. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2014, 116, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, K.; Bohanec, B.; Hansen, M. Microspore culture of white cabbage, Brassica oleracea var. capitata L.: Genetic improvement of non-responsive cultivars and effect of genome doubling agents. Plant Breed. 1999, 118, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Zhou, W.; Hagberg, P. High frequency spontaneous production of doubled haploid plants in microspore cultures of Brassica rapa ssp. chinensis. Euphytica 2003, 134, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Fang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Sun, P. Chromosome doubling of microspore-derived plants from cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata L.) and broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.-l.; Aoki, S.; Takahata, Y. RAPD markers linked to microspore embryogenic ability in Brassica crops. Euphytica 2003, 131, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Han, F.; Kong, C.; Fang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Lv, H. Rapid introgression of the Fusarium wilt resistance gene into an elite cabbage line through the combined application of a microspore culture, genome background analysis, and disease resistance-specific marker assisted foreground selection. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.S.; Takahira, J.; Atri, C.; Samans, B.; Hayward, A.; Cowling, W.A.; Batley, J.; Nelson, M.N. Microspore culture reveals complex meiotic behaviour in a trigenomic Brassica hybrid. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.S.; Lee, Y.G.; Silva, R.R.; Park, S.; Park, M.Y.; Lim, Y.P.; Choi, S.C.; Kim, C. Potential SNPs related to microspore culture in Raphanus sativus based on a single-marker analysis. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2018, 98, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, E.V.; Kozar, E.G.; Domblides, E.A. Effect of the method of microspore isolation on the efficiency of isolated microspore culture in vitro for Brassicaceae family. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsch, J.; Nitsch, C. Haploid plants from pollen grains. Science 1969, 163, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, W.S.; Huh, Y.C.; Kim, C.A.; Park, W.T.; Kim, J.H.; Jeong, J.-T.; Hur, M.; Lee, J.; Moon, Y.-H.; Ahn, S.-J. Development of Haploid Plants by Shed-Microspore Culture in Platycodon grandiflorum (Jacq.) A. DC. Plants 2024, 13, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tel-Zur, N.; Abbo, S.; Myslabodski, D.; Mizrahi, Y. Modified CTAB procedure for DNA isolation from epiphytic cacti of the genera Hylocereus and Selenicereus (Cactaceae). Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 1999, 17, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Mo, S.-Y.; Park, H.-Y. Development of S Haplotype-Specific Markers to Identify Genotypes of Self-Incompatibility in Radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Plants 2024, 13, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walley, P.G.; Carder, J.; Skipper, E.; Mathas, E.; Lynn, J.; Pink, D.; Buchanan-Wollaston, V. A new broccoli× broccoli immortal mapping population and framework genetic map: Tools for breeders and complex trait analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Xing, M.; Song, L.; Yan, J.; Lu, W.; Zeng, A. Genome-wide analysis of simple sequence repeats in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 726084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzah, N.K. Linkage Map Construction and Genetic Diversity Analysis Based on Transcriptome-Derived Markers in Brassica oleracea L. Doctoral Dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2014. Available online: https://s-space.snu.ac.kr/handle/10371/121038 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

| Donor Plant | Bud Size (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 ± 0.5 | 4 ± 0.5 | 6 ± 0.5 | |

| SJ-Ca 13 | 0.0 ± 0.00 b | 2.33 ± 0.57 a | 0.0 ± 0.00 b |

| Donor Plant | Duration of Heat Shock (h) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 24 | 48 | 72 | |

| SJ-Ca 13 | 0.0 ± 0.00 b | 2.33 ± 0.52 a | 2.00 ± 0.82 a | 0.0 ± 0.00 b |

| MS Strength | Agar Concentration | Shoot Regeneration (%) | Number of Shoots per Embryo |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/3× | 0.9% | 16.00 ± 8.94 ab | 2.00 ± 1.41 ab |

| 1/3× | 1.0% | 28.00 ± 17.88 a | 2.40 ± 1.51 a |

| 1/2× | 0.9% | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 b |

| 1/2× | 1.0% | 8.00 ± 4.47 bc | 2.00 ± 0.75 ab |

| 1× | 0.9% | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 b |

| 1× | 1.0% | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 b |

| No. of Evaluated Regenerated Plants | Number of Regenerated Plants by Ploidy Level (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Haploid | Spontaneous Doubled Haploid | Tetraploid | |

| 12 | 3 (25) | 6 (50) | 3 (25) |

| Ploidy | Plant Width (cm) | Leaf Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Control (2n) | 31.33 ± 1.15 a | 17.33 ± 1.52 b |

| Haploid | 26.33 ± 5.50 a | 12.66 ± 2.08 b |

| Spontaneous doubled haploid | 29.00 ± 3.60 a | 14.00 ± 1.00 b |

| Tetraploid | 30.33 ± 3.47 a | 16.67 ± 3.05 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choi, S.B.; Mo, S.Y.; Park, H.Y. Induction and Regeneration of Microspore-Derived Embryos for Doubled Haploid Production in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). Plants 2026, 15, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020221

Choi SB, Mo SY, Park HY. Induction and Regeneration of Microspore-Derived Embryos for Doubled Haploid Production in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). Plants. 2026; 15(2):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020221

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Su Bin, Suk Yeon Mo, and Han Yong Park. 2026. "Induction and Regeneration of Microspore-Derived Embryos for Doubled Haploid Production in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata)" Plants 15, no. 2: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020221

APA StyleChoi, S. B., Mo, S. Y., & Park, H. Y. (2026). Induction and Regeneration of Microspore-Derived Embryos for Doubled Haploid Production in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). Plants, 15(2), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020221