QTL/Segment Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis for Oil Content Using a Wild Soybean Chromosome Segment Substitution Line Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotypic Variation of Oil Content in the SojaCSSLP5

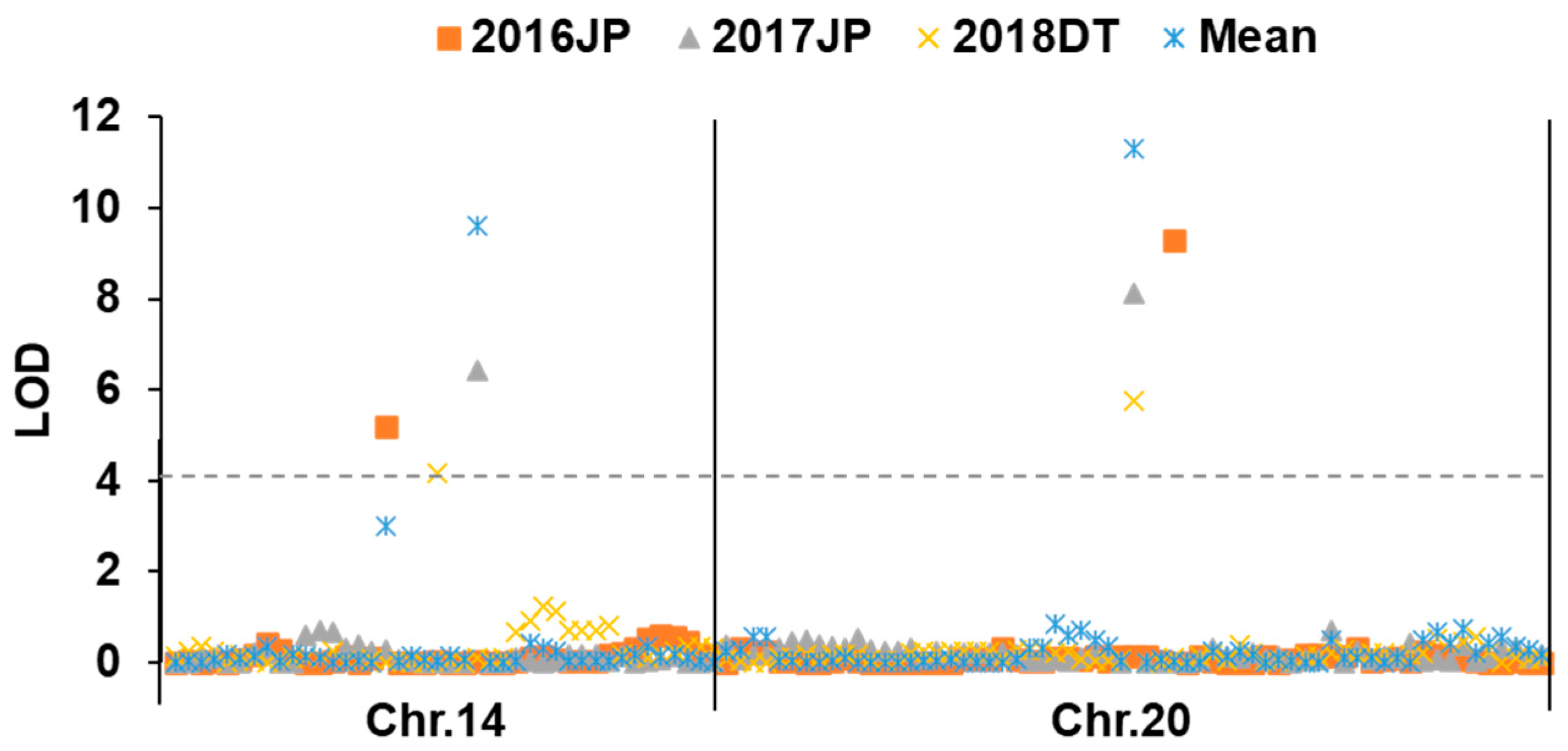

2.2. Identification of Wild Segments Related to Oil Content

2.3. Validation of Candidate Gene Related to Oil Content

3. Discussion

3.1. The Utility of CSSL Populations in Deciphering Domestication Traits

3.2. The Complex Genetic Network Governing Soybean Oil Domestication

3.3. Candidate Gene Prediction and Putative Molecular Mechanisms

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Field Trial Design and Phenotypic Measurement

4.3. Statistical Analysis

4.4. Segment/QTL Mapping

4.5. Candidate Gene Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSSL | Chromosome Segment Substitution Line |

| LOD | Logarithm of odds |

| PVE | Percentage of phenotypic variation explained by individual QTL |

| QTL | Quantitative trait locus |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

References

- Qi, Z.M.; Guo, C.C.; Li, H.Y.; Qiu, H.M.; Li, H.; Jong, C.; Yu, G.L.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, L.M.; Wu, X.X.; et al. Natural variation in Fatty Acid 9 is a determinant of fatty acid and protein content. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, T.E.; Cahoon, E.B. Soybean oil: Genetic approaches for modification of functionality and total content. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, J.P.; Yu, X.X.; Zhang, D.; Chang, H.; Li, W.; Song, H.F.; Cui, Z.; Wang, P.; Luo, Y.X.; et al. Structural variation of mitochondrial genomes sheds light on evolutionary history of soybeans. Plant J. 2021, 108, 1456–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.M.; Liu, J.Q.; Jiang, A.H.; Li, X.; Tan, P.T.; Liu, C.; Gong, X.; Sun, H.; Du, C.Z.; Zhang, J.J.; et al. QTL mapping and multi-omics identify candidate genes for protein and oil in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2025, 138, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevinger, E.M.; Biyashev, R.; Haak, D.; Song, Q.J.; Pilot, G.; Maroof, M.A.S. Identification of quantitative trait loci controlling soybean seed protein and oil content. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, Q.; Yang, H.; Xiang, S.; Zhao, T.; Gai, J. Development of a chromosome segment substitution line population with wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. et Zucc.) as donor parent. Euphytica 2013, 189, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Yang, H.; Xiang, S.; Tian, D.; Wang, W.; Zhao, T.; Gai, J.; Singh, R. Fine mapping of the genetic locus L1 conferring black pods using a chromosome segment substitution line population of soybean. Plant Breed. 2015, 134, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, W.; He, Q.; Xiang, S.; Tian, D.; Zhao, T.; Gai, J. Chromosome segment detection for seed size and shape traits using an improved population of wild soybean chromosome segment substitution lines. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.H.; Wang, W.B.; He, Q.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Liu, C.; Xing, G.N.; Zhang, T.J.; Gai, J.Y. Identification of QTL/segments related to agronomic traits using CSSL population under multiple environments. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2015, 48, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, X.N.; Wang, W.B.; Hu, X.Y.; Han, W.; He, Q.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Xiang, S.H.; Gai, J.Y. Identifying wild versuscultivated gene-alleles conferring seed coat color and days to flowering in soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Yang, S.N.; Zhang, K.; He, J.B.; Wu, C.H.; Ren, Y.H.; Gai, J.Y.; Li, Y. Natural variation and selection in affect soybean seed oil content. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1651–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.B.A.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.F.; Liang, S.; Fan, L.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Y.Q.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, G.A.; Liu, S.L.; et al. Natural allelic variation of controlling seed size and quality in soybean. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1807–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.K.; Wang, Y.Z.; Shang, P.; Yang, C.; Yang, M.M.; Huang, J.X.; Ren, B.Z.; Zuo, Z.H.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Li, W.B.; et al. Overexpression of soybean GmWRI1a stably increases the seed oil content in soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.M.; Du, C.H.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.Z.; Bao, G.G.; Huang, J.X.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Zhang, S.Z.; Xu, P.F.; Teng, W.L.; et al. The transcription factors GmVOZ1A and GmWRI1a synergistically regulate oil biosynthesis in soybean. Plant Physiol. 2024, 197, kiae485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.D.; Xian, P.Q.; Cheng, Y.B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.K.; He, Z.H.; Xiong, C.W.; Guo, Z.B.; Chen, Z.C.; Jiang, H.Q.; et al. Natural variation of GmFATA1B regulates seed oil content and composition in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 2368–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettel, W.; Zhang, H.Y.; Li, Y.; Qiao, Z.Z.; Jiang, H.; Hou, D.Y.; Song, Q.J.; Pantalone, V.R.; Song, B.H.; Yu, D.Y.; et al. POWR1 is a domestication gene pleiotropically regulating seed quality and yield in soybean. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Ma, R.R.; Huang, W.X.; Hou, J.J.; Fang, C.; Wang, L.S.; Yuan, Z.H.; Sun, Q.; Dong, X.H.; et al. Identification of reveals a selection involving hitchhiking of seed morphology and oil content during soybean domestication. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1110–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.T.; Jiang, Z.F.; Han, Y.P.; Teng, W.L.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.B. Identification of quantitative trait loci underlying seed protein and oil contents of soybean across multi-genetic backgrounds and environments. Plant Breed. 2013, 132, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.S.; Zhang, Z.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Xin, D.W.; Qiu, H.M.; Shan, D.P.; Shan, C.Y.; Hu, G.H. QTL analysis of major agronomic traits in soybean. Agric. Sci. Chin. 2007, 6, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajuddin, T.; Watanabe, S.; Yamanaka, N.; Harada, K. Analysis of quantitative trait loci for protein and lipid contents in soybean seeds using recombinant inbred lines. Breed. Sci. 2003, 53, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.M.; Wu, Q.; Han, X.; Sun, Y.N.; Du, X.Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Jiang, H.W.; Hu, G.H.; Chen, Q.S. Soybean oil content QTL mapping and integrating with meta-analysis method for mining genes. Euphytica 2011, 179, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, M.; Cober, E.R.; Rajcan, I. Genetic control of soybean seed oil: I. QTL and genes associated with seed oil concentration in RIL populations derived from crossing moderately high-oil parents. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.Z.; Yu, Y.L.; Wang, S.F.; Lian, Y.; Wang, T.F.; Wei, Y.L.; Gong, P.T.; Liu, X.Y.; Fang, X.J.; Zhang, M.C. QTL mapping of isoflavone, oil and protein contents in soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.). Agric. Sci. Chin. 2010, 9, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diers, B.W.; Keim, P.; Fehr, W.R.; Shoemaker, R.C. Rflp analysis of soybean seed protein and oil content. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1992, 83, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebolt, A.M.; Shoemaker, R.C.; Diers, B.W. Analysis of a quantitative trait locus allele from wild soybean that increases seed protein concentration in soybean. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 1438–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, J.E.; Chase, K.; Macrander, M.; Graef, G.L.; Chung, J.; Markwell, J.P.; Germann, M.; Orf, J.H.; Lark, K.G. Soybean response to water: A QTL analysis of drought tolerance. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Babka, H.L.; Graef, G.L.; Staswick, P.E.; Lee, D.J.; Cregan, P.B.; Shoemaker, R.C.; Specht, J.E. The seed protein, oil, and yield QTL on soybean linkage group I. Crop Sci. 2003, 43, 1053–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Takayama, K.; Ujiie, A.; Yamada, T.; Abe, J.; Kitamura, K. Genetic relationship between lipid content and linolenic acid concentration in soybean seeds. Breed. Sci. 2008, 58, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.P.; Teng, W.L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, L.; Li, D.M.; Li, W.B. Unconditional and conditional QTL underlying the genetic interrelationships between soybean seed isoflavone, and protein or oil contents. Plant Breed. 2015, 134, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.B.; Li, X.Y.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Y.H.; Qin, M.; Zhu, H.T.; Zeng, R.Z.; Fu, X.L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zhang, G.Q. Characterization of epistatic interaction of QTLs LH8 and EH3 controlling heading date in rice. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, H.X.; Xu, G.Y.; Deng, K.L.; Yu, J.J.; Xiang, S.Q.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, Q.L.; Li, R.X.; Li, M.M.; et al. QTL analysis of Z414, a chromosome segment substitution line with short, wide grains, and substitution mapping of in rice. Rice 2022, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, J.M.; Jiang, L.; Liu, L.L.; Wei, X.J.; Xiao, Y.H.; Zhang, L.J.; Zhao, Z.G.; Zhai, H.Q.; Wan, J.M. Construction of a new set of rice chromosome segment substitution lines and identification of grain weight and related traits QTLs. Breed. Sci. 2010, 60, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canady, M.A.; Meglic, V.; Chetelat, R.T. A library of Solanum lycopersicoides introgression lines in cultivated tomato. Genome 2005, 48, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avgousti, D.C.; Cecere, G.; Grishok, A. The Conserved PHD1-PHD2 Domain of ZFP-1/AF10 Is a Discrete Functional Module Essential for Viability in. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.; Choi, D.; Lee, J. Fine mapping of the genic male-sterile ms 1 gene in Capsicum annuum L. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, A.; Liu, R.; Liu, C.C.; Wu, F.; Su, H.; Zhou, S.Z.; Huang, M.; Tian, X.H.; Jia, H.T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Mutation of the gene encoding the PHD-type transcription factor SAB23 confers submergence tolerance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Huang, J.; Hao, Y.J.; Zou, H.F.; Wang, H.W.; Zhao, J.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, W.K.; Ma, B.; Zhang, J.S.; et al. Soybean GmPHD-Type transcription regulators improve stress tolerance in transgenic arabidopsis plants. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Guo, P.; Hao, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, W.; Zhao, L.; Luo, W.; He, J.; et al. Differential SW16.1 allelic effects and genetic backgrounds contributed to increased seed weight after soybean domestication. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1734–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Env. | Parents | SojaCSSLP5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN1138-2 | N24852 | Range (%) | Mean (%) | Skewness | Kurtosis | CV (%) | h2 (%) | |

| 2016JP | 19.29 | 10.20 | 17.16–20.58 | 19.31 | −0.73 | 0.97 | 3.40 | 61.59 |

| 2017JP | 19.65 | - | 16.72–20.31 | 19.06 | −0.80 | 0.65 | 2.90 | 77.37 |

| 2018DT | 20.27 | - | 17.30–20.90 | 19.68 | −0.80 | 0.89 | 2.94 | 70.54 |

| Mean | 19.79 | 10.20 | 17.37–20.24 | 19.35 | −1.14 | 1.96 | 3.08 | 68.42 |

| Source of Variation | DF | MS | F Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line | 154 | 2.08 | 3.07 | <0.0001 |

| Error (Line) | 311.78 | 0.67 | ||

| Env. | 2 | 43.63 | 6.19 | 0.0307 |

| Error (Env.) | 6.57 | 7.04 | ||

| Rep (Env.) | 6 | 6.76 | 18.94 | <0.0001 |

| Line × Env. | 309 | 0.68 | 1.91 | <0.0001 |

| Error (MS) | 863 | 0.36 |

| QTL | Marker | Genome Region | Size of Region | LOD | PVE (%) | Add | Reported QTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qOC14 | Gm14_26 | 43,138,590–47,789,260 | 4.65 | 9.60 | 17.87 | −0.35 | Seed oil 43-6 [18], Seed oil 28-1 [19], Seed oil 43-5 [18], Seed oil 34-2 [20], Seed oil 24-17 [21], Seed oil 37-4 [22], Seed oil 43-2 [18], Seed oil 30-4 [23], Seed oil 43-3 [18] |

| qOC20 | Gm20_29 | 24,336,033–33,481,640 | 9.15 | 11.30 | 21.59 | −0.42 | Seed oil 2-1 [24], Seed oil 2-2 [24], Seed oil 11-1 [25], Seed oil 12-1 [25], Seed oil 13-4 [26], Seed oil 15-1 [27], Seed oil 24-29 [21], Seed oil 24-30 [21], Seed oil 32-3 [28], Seed oil 42-19 [29], Seed oil 43-17 [18] |

| Line | Oil Content | Gm14_26 | Gm20_29 | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN1138-2 | 19.79 | A | A | |

| L005 | 18.87 | B | A | * |

| L047 | 18.66 | B | A | ** |

| L050 | 18.73 | B | A | * |

| L086 | 18.79 | B | A | * |

| L113 | 19.37 | B | A | ns |

| L144 | 18.30 | B | A | ** |

| L150 | 19.08 | B | A | * |

| L182 | 17.95 | B | A | *** |

| L092 | 18.50 | B | B | ** |

| L093 | 18.26 | B | B | ** |

| L163 | 17.37 | B | B | *** |

| L174 | 17.87 | B | B | *** |

| L049 | 18.45 | A | B | ** |

| L076 | 18.85 | A | B | * |

| L151 | 18.51 | A | B | ** |

| L157 | 18.48 | A | B | ** |

| L173 | 18.64 | A | B | * |

| L176 | 19.10 | A | B | ** |

| Gene | Function | Parents | Expression Difference (FPKM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14seed | 21seed | 28seed | 35seed | Leaf | |||

| Glyma.14G179800 | PHD-type zinc finger plants domain-containing protein | NN1138-2 | 16.35 | 7.63 | 6.09 | 6.84 | 16.35 |

| N24852 | 19.02 | 12.89 | 5.42 | 0.55 | 19.02 | ||

| Glyma.20G085100 | CCT motif-containing protein | NN1138-2 | 0.59 | 1.13 | 0.57 | 1.31 | 0.12 |

| N24852 | 2.23 | 2.26 | 1.45 | 0.19 | 0.64 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, C.; Ren, J.; Wen, H.; Zhen, C.; Han, W.; Chen, X.; He, J.; Liu, F.; Sun, L.; Xing, G.; et al. QTL/Segment Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis for Oil Content Using a Wild Soybean Chromosome Segment Substitution Line Population. Plants 2026, 15, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020177

Liu C, Ren J, Wen H, Zhen C, Han W, Chen X, He J, Liu F, Sun L, Xing G, et al. QTL/Segment Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis for Oil Content Using a Wild Soybean Chromosome Segment Substitution Line Population. Plants. 2026; 15(2):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020177

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Cheng, Jinxing Ren, Huiwen Wen, Changgeng Zhen, Wei Han, Xianlian Chen, Jianbo He, Fangdong Liu, Lei Sun, Guangnan Xing, and et al. 2026. "QTL/Segment Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis for Oil Content Using a Wild Soybean Chromosome Segment Substitution Line Population" Plants 15, no. 2: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020177

APA StyleLiu, C., Ren, J., Wen, H., Zhen, C., Han, W., Chen, X., He, J., Liu, F., Sun, L., Xing, G., Zhao, J., Gai, J., & Wang, W. (2026). QTL/Segment Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis for Oil Content Using a Wild Soybean Chromosome Segment Substitution Line Population. Plants, 15(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020177