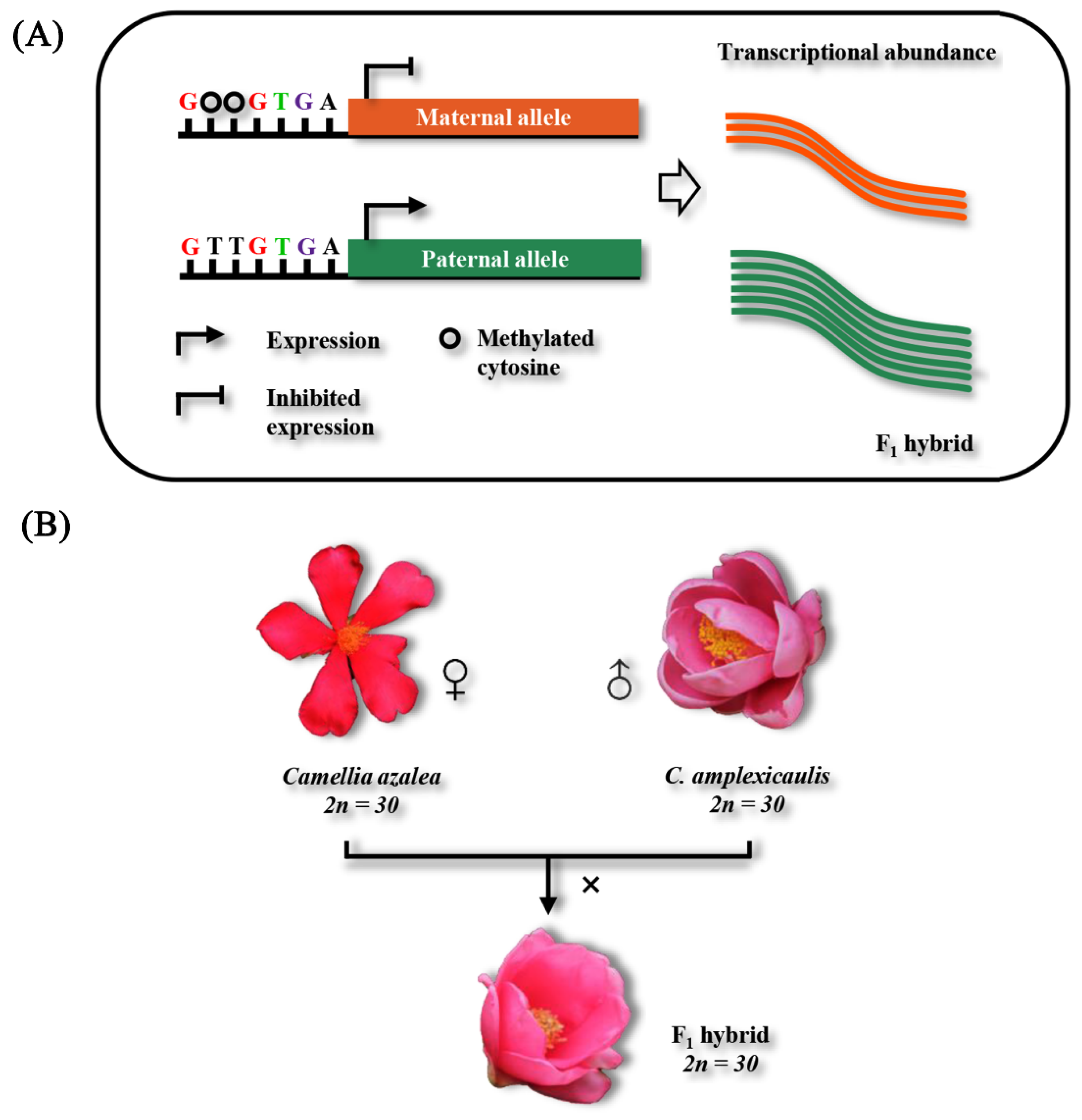

Inheritance of DNA Methylation Patterns and Its Role in Modulating Allelic Expression in Camellia F1 Hybrids

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Morphological Divergence Between the F1 Hybrids and Their Parents

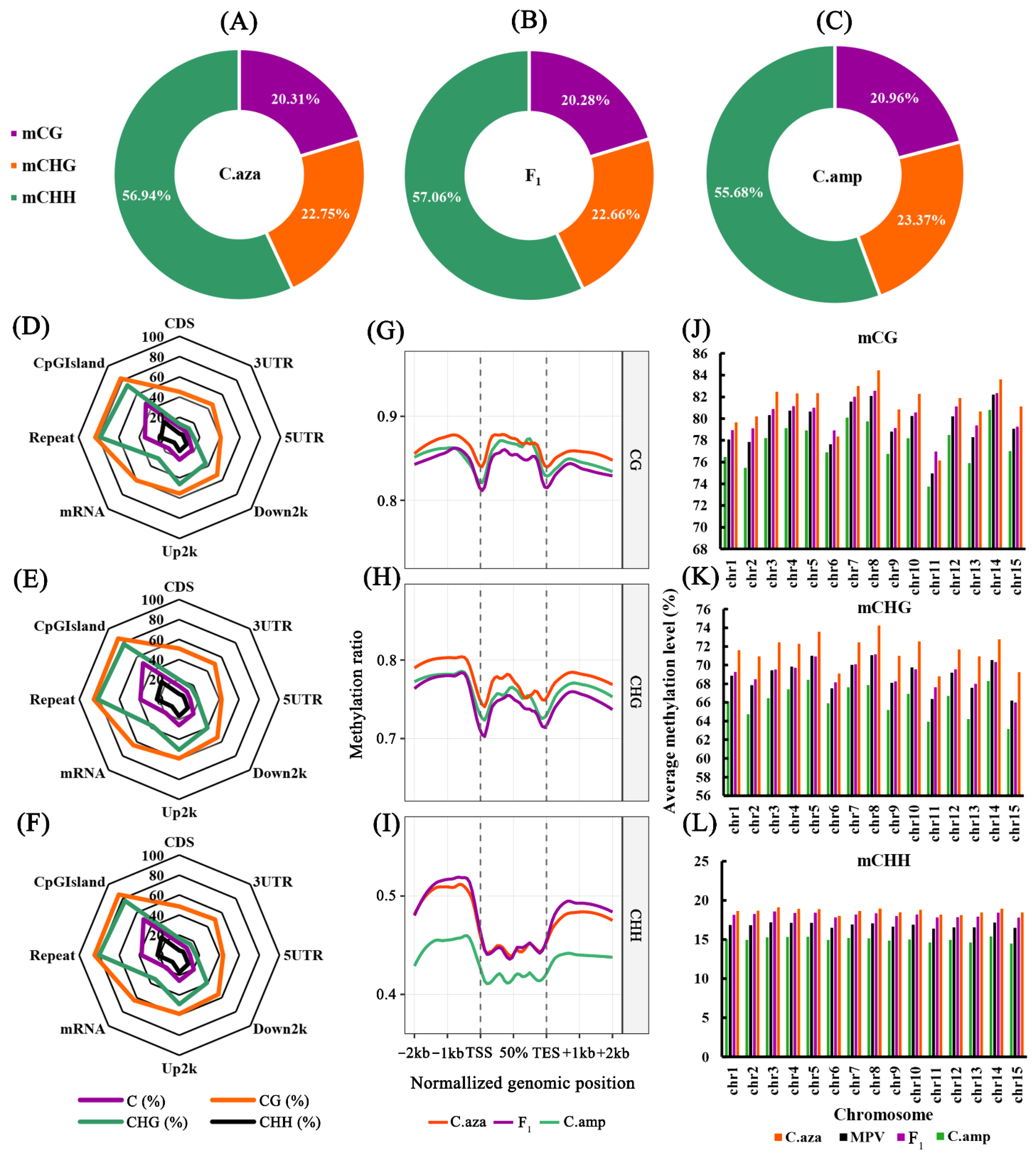

2.2. Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing and Data Alignment

2.3. The Global Methylation Profiles of the Parental Lines and F1 Hybrids

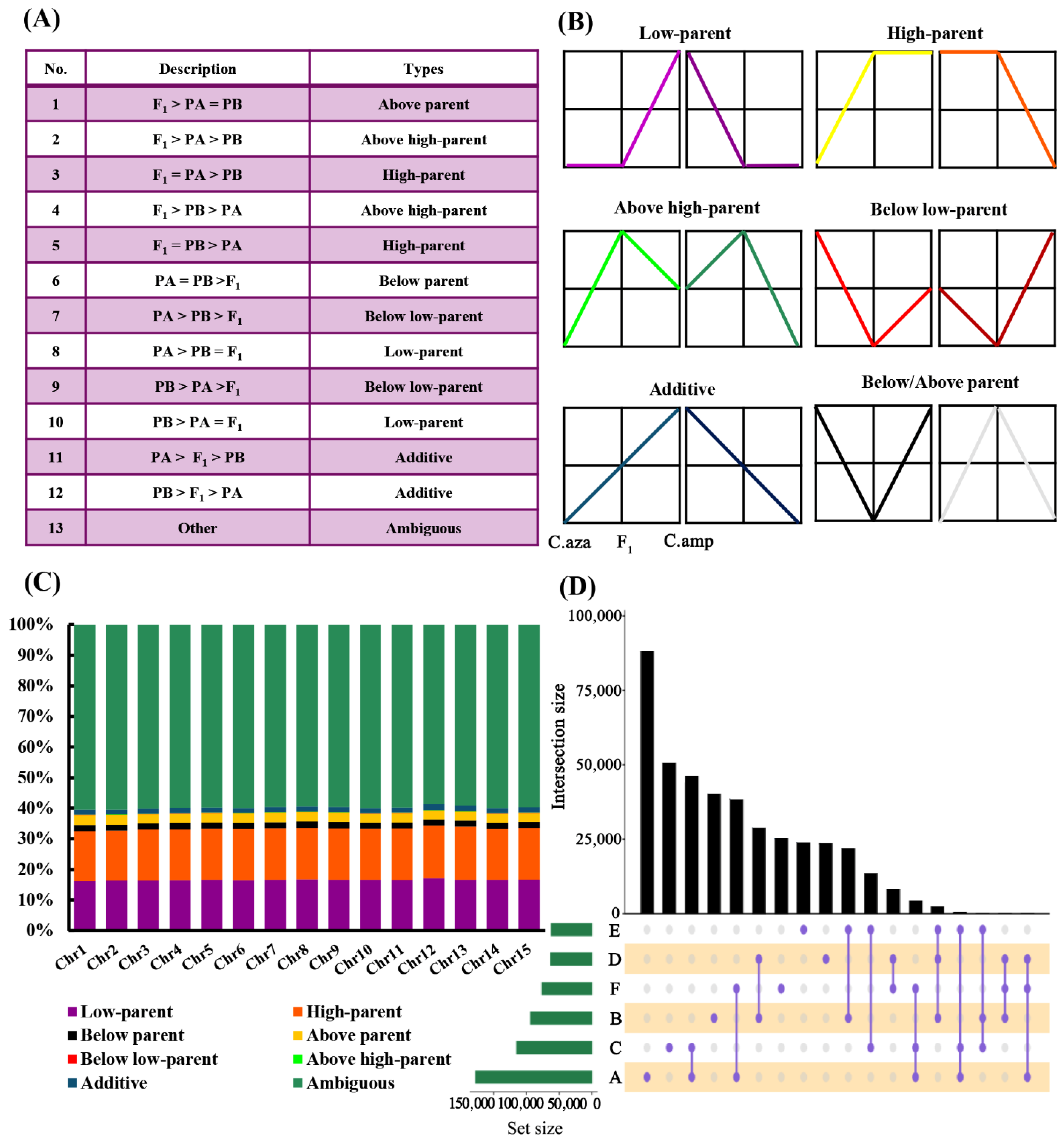

2.4. Differentially Methylated Regions Between the Parental Lines and F1 Hybrids

2.5. Differentially Methylated Sites Between the Parental Lines and F1 Hybrids

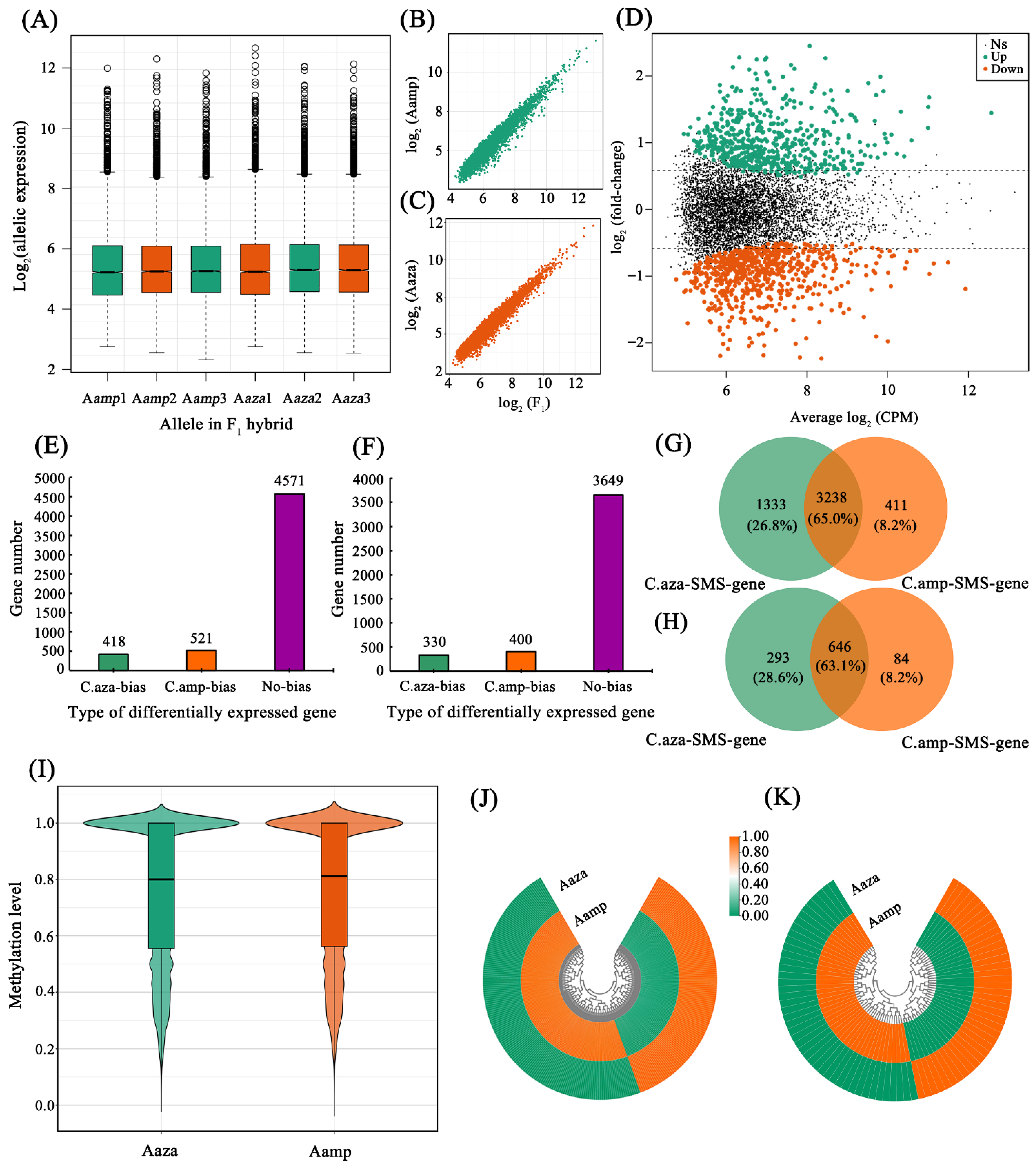

2.6. Parent-Specific Site Identification and Allelic Expression Analysis

2.7. Allele-Specific Methylation Patterns in the F1 Hybrids

3. Discussion

3.1. Cytosine Methylation Remodeling in Interspecific F1 Hybrids

3.2. Inheritance Patterns of Cytosine Methylation in Interspecific F1 Hybrids

3.3. Cytosine Methylation Balances Parental Allele Expression in Interspecific F1 Hybrids

3.4. Multiple Allele-Specific Sites May Critically Shape Phenotypes of Interspecific F1 Hybrids

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing

4.3. Data Filtering and Sequence Alignment

4.4. Differentially Methylated Regions Detection

4.5. Differentially Methylated Site Detection and Inheritance Pattern Classification

4.6. Transcriptome Data Analysis

4.7. Whole-Genome Resequencing and Parent-Specific Methylation Sites Identification

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitney, K.D.; Ahern, J.R.; Campbell, L.G.; Albert, L.P.; King, M.S. Patterns of Hybridization in Plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010, 12, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.; Albach, D.; Ansell, S.; Arntzen, J.W.; Baird, S.J.E.; Bierne, N.; Boughman, J.; Brelsford, A.; Buerkle, C.A.; Buggs, R.; et al. Hybridization and Speciation. J. Evol. Biol. 2013, 26, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, H.; He, G.; Deng, X.W. From Hybrid Genomes to Heterotic Trait Output: Challenges and Opportunities. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 66, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalba, J.V.; Runemark, A.; Meier, J.I.; Singh, P.; Wogan, G.O.U.; Sánchez-Guillén, R.; Mallet, J.; Rometsch, S.J.; Menon, M.; Seehausen, O.; et al. The Role of Hybridization in Species Formation and Persistence. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2024, 16, a041445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, X.; Huang, X. Exploring the Molecular Basis of Heterosis for Plant Breeding. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019, 62, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Hirsch, C.N.; Briggs, S.P.; Springer, N.M. Dynamic Patterns of Gene Expression Additivity and Regulatory Variation throughout Maize Development. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, S.; Seoighe, C. Perspectives on Allele-Specific Expression. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2021, 4, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Xing, F.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Che, J.; Wang, X.; Song, J.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Chen, L.-L.; et al. Patterns of Genome-Wide Allele-Specific Expression in Hybrid Rice and the Implications on the Genetic Basis of Heterosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5653–5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Valenzuela, E.; Sawers, R.H.; Cibrián-Jaramillo, A. Cis- and Trans-Regulatory Variations in the Domestication of the Chili Pepper Fruit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Mudunkothge, J.S.; Galli, M.; Char, S.N.; Davenport, R.; Zhou, X.; Gustin, J.L.; Spielbauer, G.; Zhang, J.; Barbazuk, W.B.; et al. Paternal Imprinting of Dosage-Effect Defective1 Contributes to Seed Weight Xenia in Maize. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Pierre, C.L.; Macias-Velasco, J.F.; Wayhart, J.P.; Yin, L.; Semenkovich, C.F.; Lawson, H.A. Genetic, Epigenetic, and Environmental Mechanisms Govern Allele-Specific Gene Expression. Genome Res. 2022, 32, 1042–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuchic, V.; Lurie, E.; Carrero, I.; Pawliczek, P.; Patel, R.Y.; Rozowsky, J.; Galeev, T.; Huang, Z.; Altshuler, R.C.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Allele-Specific Epigenome Maps Reveal Sequence-Dependent Stochastic Switching at Regulatory Loci. Science 2018, 361, eaar3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, E.; El Chartouni, C.; Rehli, M. Allele-specific DNA Methylation in Mouse Strains is Mainly Determined by cis-acting Sequences. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 2028–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Xing, F.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, T.; Wu, B.; Shao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, D.-X. Parental Variation in CHG Methylation is Associated with Allelic-Specific Expression in Elite Hybrid Rice. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 1025–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Luo, H.; Yao, J.; Guo, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Meng, D. Characterization of Genes That Exhibit Genotype-Dependent Allele-Specific Expression and Its Implications for the Development of Maize Kernel. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Luo, H.; Yao, J.; Guo, Q.; Yu, S.; Ruan, Y.; Li, F.; Jin, W.; Meng, D.; Tricker, P. The Conservation of Allelic DNA Methylation and Its Relationship with Imprinting in Maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 1376–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, X.-K.; Fan, W.; Yan, D.-F.; Zhong, N.-S.; Gao, J.-Y.; Zhang, W.-J. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Hybridization-Induced Genome Shock in an Interspecific F1 Hybrid from Camellia. Genome 2018, 61, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, H.; Guo, Y.; Wan, H.; Zhang, X.; Scossa, F.; Alseekh, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, P.; et al. Genome Assembly of Wild Tea Tree Dasz Reveals Pedigree and Selection History of Tea Varieties. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.J.; Sun, L.F.; Shan, X.H.; Wu, Y.; Su, S.Z.; Li, S.P.; Liu, H.K.; Han, J.Y.; Yuan, Y.P. Analysis of DNA Methylation Patterns and Levels in Maize Hybrids and Their Parents. Genet. Mol. Res. 2014, 13, 8458–8468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Chen, S.; Qi, X.; Fang, W.; Guan, Z.; Teng, N.; Liao, Y.; Chen, F. Rapid Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations under Intergeneric Genomic Shock in Newly Synthesized Chrysanthemum morifolium × Leucanthemum paludosum Hybrids (Asteraceae). Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigal, M.; Becker, C.; Pélissier, T.; Pogorelcnik, R.; Devos, J.; Ikeda, Y.; Weigel, D.; Mathieu, O. Epigenome Confrontation Triggers Immediate Reprogramming of DNA Methylation and Transposon Silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana F1 Epihybrids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2083–E2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisod, C.; Salmon, A.; Zerjal, T.; Tenaillon, M.; Grandbastien, M.A.; Ainouche, M. Rapid Structural and Epigenetic Reorganization Near Transposable Elements in Hybrid and Allopolyploid Genomes in Spartina. New Phytol. 2009, 184, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; He, H.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Guo, L.; Peng, Z.; He, G.; Zhong, S.; Qi, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of DNA Methylation and Gene Expression Changes in Two Arabidopsis Ecotypes and Their Reciprocal Hybrids. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 875–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikaard, C.S.; Mittelsten Scheid, O. Epigenetic Regulation in Plants. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a019315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Aldridge, B.; Vickers, M.; Higgins, J.D.; Feng, X. Sexual-lineage-specific DNA methylation regulates meiosis in Arabidopsis. Nat. Genet. 2017, 50, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, A.; Rando, O.J. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, K.J.F.; Jansen, J.J.; van Dijk, P.J.; Biere, A. Stress-Induced DNA Methylation Changes and Their Heritability in Asexual Dandelions. New Phytol. 2009, 185, 1108–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillo, D.; Mukherjee, S.; Vinson, C. Inheritance of Cytosine Methylation. J. Cell Physiol. 2016, 231, 2346–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calarco, J.P.; Borges, F.; Donoghue, M.T.A.; Van Ex, F.; Jullien, P.E.; Lopes, T.; Gardner, R.; Berger, F.; Feijó, J.A.; Becker, J.D.; et al. Reprogramming of DNA Methylation in Pollen Guides Epigenetic Inheritance via Small RNA. Cell 2012, 151, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.A.; Jacobsen, S.E. Establishing, Maintaining and Modifying DNA Methylation Patterns in Plants and Animals. Nat. Rev Genet. 2010, 11, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Dynamics and Function of DNA Methylation in Plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villicaña, S.; Bell, J.T. Genetic Impacts on DNA Methylation: Research Findings and Future Perspectives. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taudt, A.; Colomé-Tatché, M.; Johannes, F. Genetic Sources of Population Epigenomic Variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.-L.; Jia, K.-H.; Bao, Y.-T.; Nie, S.; Tian, X.-C.; Yan, X.-M.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Li, Z.-C.; Zhao, S.-W.; Ma, H.-Y.; et al. High-Quality Genome Assembly Enables Prediction of Allele-Specific Gene Expression in Hybrid Poplar. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Fan, R.; Meng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Laroche, A.; Liu, D.; Zhao, W.; Yu, X. Molecular Identification and Acquisition of Interacting Partners of A Novel Wheat F-box/Kelch Gene TaFBK. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 112, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H. The Unfolding Drama of Flower Development: Recent Results from Genetic and Molecular Analyses. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qiao, Y.; Li, C.; Hou, B. The NAC Transcription Factors Play Core Roles in Flowering and Ripening Fundamental to Fruit Yield and Quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1095967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausin, I.; Mockler, T.C.; Chory, J.; Jacobsen, S.E. IDN1 and IDN2 are Required for De Novo DNA Methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 1325–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basso, A.; Barcaccia, G.; Galla, G. Annotation and Expression of IDN2-like and FDM-like Genes in Sexual and Aposporous Hypericum perforatum L. accessions. Plants 2019, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Wu, K.; Sharma, S.; Xing, F.; Wu, S.-Y.; Tyagi, A.; Deshpande, R.; Singh, R.; Wabitsch, M.; Mo, Y.-Y.; et al. Exosomal MiR-1304-3p Promotes Breast Cancer Progression in African Americans by Activating Cancer-associated Adipocytes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, R.C.; Lu, J.; Zhang, C.; Mosher, R.A.; Baulcombe, D.C.; Chen, Z.J. Maternal Small RNAs Mediate Spatial-Temporal Regulation of Gene Expression, Imprinting, and Seed Development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2761–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Thrimawithana, A.; Ding, T.; Guo, J.; Gleave, A.; Chagné, D.; Ampomah-Dwamena, C.; Ireland, H.S.; Schaffer, R.J.; Luo, Z.; et al. Transposon Insertions Regulate Genome-Wide Allele-Specific Expression and Underpin Flower Colour Variations in Apple (Malus spp.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.-Y.; Liu, X.K.; Zhao, Q.M. Illustrations of the New Camellia hybrids that Bloom Year-Round; Zhejiang Science and Technology Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y.; Li, W. BSMAP: Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequence MAPping Program. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, X.; Yao, D.; Song, Y.; Fan, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Heterosis and Differential DNA Methylation in Soybean Hybrids and Their Parental Lines. Plants 2022, 11, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tang, Y.-W.; Qi, J.; Liu, X.-K.; Yan, D.-F.; Zhong, N.-S.; Tao, N.-Q.; Gao, J.-Y.; Wang, Y.-G.; Song, Z.-P.; et al. Effects of Parental Genetic Divergence on Gene Expression Patterns in Interspecific Hybrids of Camellia. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows–Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koboldt, D.C.; Chen, K.; Wylie, T.; Larson, D.E.; McLellan, M.D.; Mardis, E.R.; Weinstock, G.M.; Wilson, R.K.; Ding, L. VarScan: Variant Detection in Massively Parallel Sequencing of Individual and Pooled Samples. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2283–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Clean Data Size (bp) | Mapped Reads | Mapping Rate (%) | Uniquely Mapped Reads | Uniquely Mapping Rate (%) | Bisulfite Conversion Rate (%) * | Average Depth (X) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C.amp | 103,604,864,200 | 771,474,941 | 74.46 | 566,814,667 | 54.71 | 99.39 | 16.57 |

| F1 | 108,717,190,200 | 761,566,451 | 75.44 | 548,873,456 | 54.37 | 99.38 | 17.12 |

| C.aza | 109,177,865,800 | 809,930,929 | 74.18 | 578,004,884 | 52.94 | 99.34 | 16.94 |

| Sample ID | mC Number | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mCG | mCHG | mCHH | Total | |

| C.amp | 35,035,237 | 39,065,979 | 93,074,792 | 167,176,008 |

| F1 hybrid | 43,862,913 | 49,018,324 | 123,429,484 | 216,310,721 |

| C.aza | 42,652,315 | 47,769,161 | 119,565,996 | 209,987,472 |

| Sample ID | Clean Reads | Clean Base | Read Length | Q20 (%) | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C.amp | 120,130,447 | 36,039,134,100 | PE150 | 98.53 | 37.77 |

| F1 | 107,593,530 | 32,278,059,000 | PE150 | 98.29 | 39.02 |

| C.aza | 117,701,194 | 35,310,358,200 | PE150 | 98.37 | 39.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Xie, L.-J.; Yan, S.-R.; Huang, Q.-L.; Xu, C.-L.; Li, Z.-F.; Tang, Y.-W.; Liu, X.-K.; Zhong, N.-S.; Zhang, W.-J. Inheritance of DNA Methylation Patterns and Its Role in Modulating Allelic Expression in Camellia F1 Hybrids. Plants 2026, 15, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010094

Zhang M, Xie L-J, Yan S-R, Huang Q-L, Xu C-L, Li Z-F, Tang Y-W, Liu X-K, Zhong N-S, Zhang W-J. Inheritance of DNA Methylation Patterns and Its Role in Modulating Allelic Expression in Camellia F1 Hybrids. Plants. 2026; 15(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Min, Lin-Jian Xie, Shu-Rong Yan, Qi-Ling Huang, Cai-Lin Xu, Zi-Fei Li, Yi-Wei Tang, Xin-Kai Liu, Nai-Sheng Zhong, and Wen-Ju Zhang. 2026. "Inheritance of DNA Methylation Patterns and Its Role in Modulating Allelic Expression in Camellia F1 Hybrids" Plants 15, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010094

APA StyleZhang, M., Xie, L.-J., Yan, S.-R., Huang, Q.-L., Xu, C.-L., Li, Z.-F., Tang, Y.-W., Liu, X.-K., Zhong, N.-S., & Zhang, W.-J. (2026). Inheritance of DNA Methylation Patterns and Its Role in Modulating Allelic Expression in Camellia F1 Hybrids. Plants, 15(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010094