Functional Characterization of a Root-Preferential and Stress-Inducible Promoter of Eca-miR482f in Eucalyptus camaldulensis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Expression Profiling of Eca-miR482f in E. camaldulensis

2.1.1. Organ-Specific Expression of Eca-miR482f

2.1.2. Expression Response of Eca-miR482f to Cold Stress

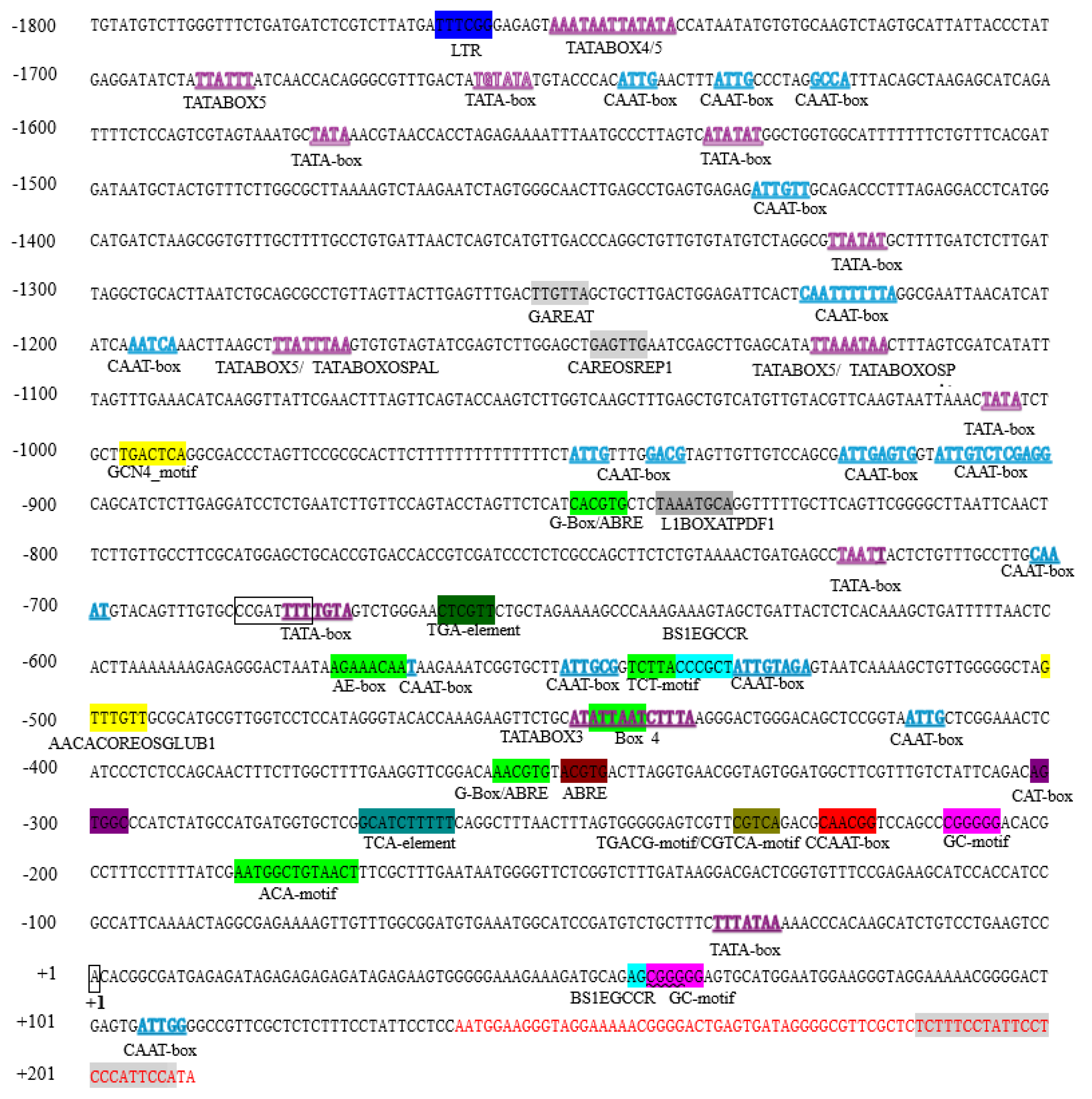

2.2. Cloning and Sequence Characterization of the Eca-miR482f Promoter

2.2.1. Cloning of the Eca-miR482f Promoter

2.2.2. Bioinformatics Prediction of Cis-Acting Elements in the Eca-miR482f Promoter

2.3. Transient Expression Analysis of the Truncated Eca-miR482f Promoters in Tobacco

2.3.1. LUC Fluorescence Activity Assay

2.3.2. GUS Histochemical Staining

2.3.3. GUS Activity Under Abiotic Stress and Exogenous Hormone Treatments

2.4. Stable Expression Analysis of the Eca-miR482f Promoter in Arabidopsis

2.4.1. Tissue-Specific and Developmental Expression of the Eca-miR482f Promoter

2.4.2. Stress Responsiveness of the Eca-miR482f Promoter

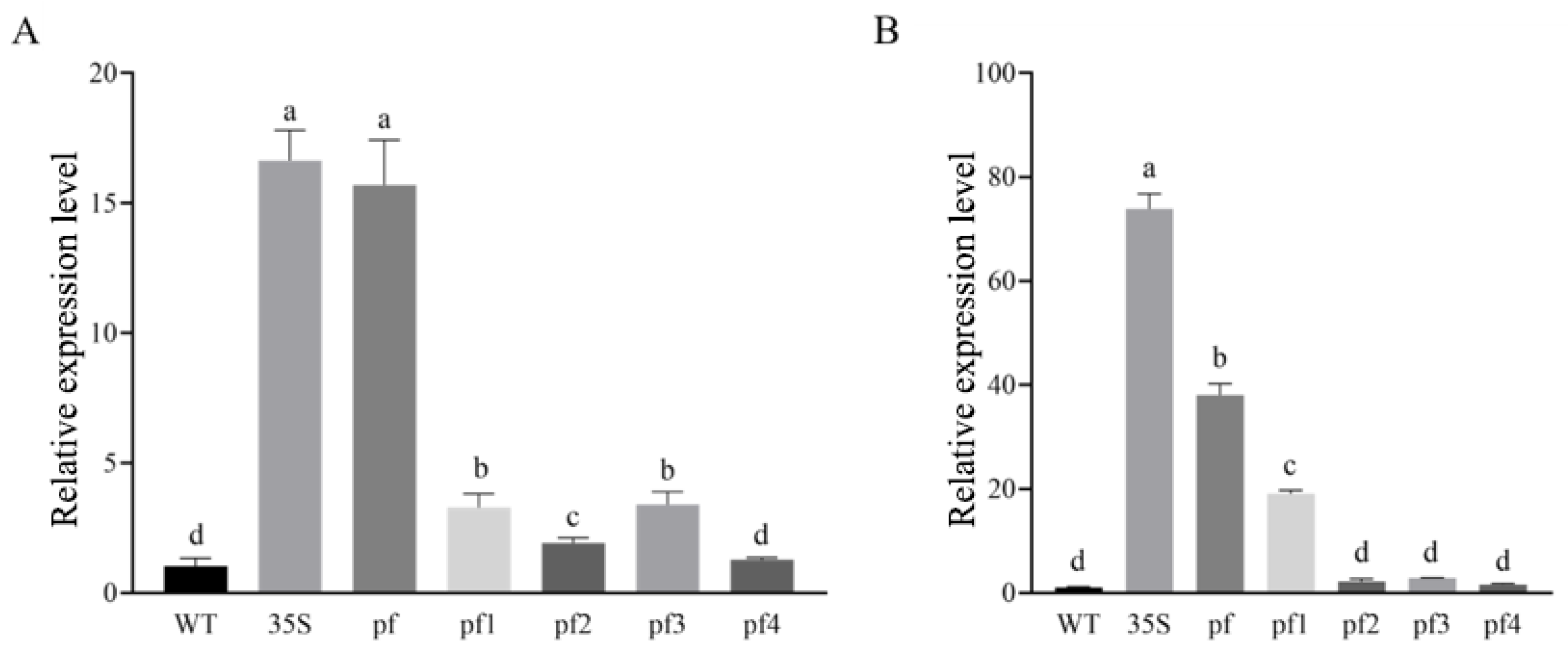

2.4.3. Driving Activity of Truncated Eca-miR482f Promoter in Transgenic Arabidopsis

- (1)

- GUS Histochemical Staining

- (2)

- qRT-PCR Analysis of GUS Expression

3. Discussion

3.1. Functional Implications of Eca-miR482f Expression Patterns

3.2. Cis-Acting Elements of the Eca-miR482f Promoter

3.3. Functional Validation of the Eca-miR482f Promoter

3.4. Modular Functional Regions of the Eca-miR482f Promoter Governing Organ Specificity

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

4.3. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of the Eca-miR482f Promoter

4.4. Construction of Promoter Reporter Vectors

4.5. Transient Expression Assays in Tobacco

4.6. Stable Transformation Assays in Arabidopsis

4.7. Data Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Waseem, M.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhai, J.; Xia, R. MicroRNA482/2118, a miRNA superfamily essential for both disease resistance and plant development. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 2047–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.H.; Jin, S.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wilson, I. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated saturated mutagenesis of the cotton MIR482 family for dissecting the functionality of individual members in disease response. Plant Direct 2022, 6, e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Park, G.; Atamian, H.S.; Han, C.S.; Stajich, J.E.; Kaloshian, I.; Borkovich, K.A. MicroRNAs suppress NB domain genes in tomato that confer resistance to Fusarium oxysporum. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Ren, C.; Xue, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, N.; Sheng, C.; Jiang, H.; Bai, D. Small RNA and degradome deep sequencing reveals the roles of microRNAs in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cold response. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 920195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhao, M.; Chen, C.; Ma, X.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hao, Y.; et al. MicroRNA482/2118 is lineage-specifically involved in gibberellin signaling via the regulation of GID1 expression by targeting noncoding PHAS genes and subsequently instigated phasiRNAs. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenza, C.; Aleman, L.; Sengupta-Gopalan, C. Targeting transgene expression in research, agricultural, and environmental applications: Promoters used in plant transformation. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2004, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.J.; Madhav, M.S.; Kumar, G.R.; Goel, A.K.; Umakanth, B.; Jahnavi, B.; Viraktamath, B.C. Identification of abiotic stress miRNA transcription factor binding motifs (TFBMs) in rice. Gene 2013, 531, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Li, L. Comparative analysis of microRNA promoters in Arabidopsis and rice. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2013, 11, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjanawattanawong, S.; Tangphatsornruang, S.; Triwitayakorn, K.; Ruang-areerate, P.; Sangsrakru, D.; Poopear, S.; Somyong, S.; Narangajavana, J. Characterization of rubber tree microRNA in phytohormone response using large genomic DNA libraries, promoter sequence and gene expression analysis. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, Z.Y.; Zhou, Q.; Lin, Y.Z. High-throughput miRNA sequencing and identification of a novel ICE1-targeting miRNA in response to low temperature stress in Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Plant Biol. 2023, 25, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.L.; Zeng, Q.Q.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, Z.B. Identification and expression analysis of miR482a in Pinus densata. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2021, 60, 135–138, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.R.; Dong, Q.; Wang, Y.Q.; Guo, F.Y.; Dong, X.N.; Li, Y.; Gai, Y.P.; Ji, X.L. Expression characteristics and biological function of miR482 in Mulberry. Sci. Sericologica Sin. 2021, 47, 101–110, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.Y. Study on eca-miRn33-Mediated Cold Stress Response in Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Ph.D. Thesis, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China, 2021. (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R. MicroRNA-mediated gene regulation in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Xu, J.; Gao, T.; Huang, D.; Jin, W. Molecular mechanism of modulating miR482b level in tomato with Botrytis cinerea infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Feyissa, B.A.; Amyot, L.; Aung, B.; Hannoufa, A. MicroRNA156 improves drought stress tolerance in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) by silencing SPL13. Plant Sci. 2017, 258, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, N.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Yao, N.; Cui, X.; et al. Tissue-specific regulation of Gma-miR396 family on coordinating development and low water availability responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, C.; Grotewold, E. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis core promoters. BMC Genom. 2005, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.; Barrela, R.M.; Berges, H.; Marques, C.; Loureiro, J.; Morais-Cecílio, L.; Paiva, J.A. Advancing Eucalyptus genomics: Cytogenomics reveals conservation of Eucalyptus genomes. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Ji, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Yang, G.; Yan, K.; Zhang, S.; et al. Regulation of drought tolerance in Arabidopsis involves the PLATZ4-mediated transcriptional repression of plasma membrane aquaporin PIP2;8. Plant J. 2023, 115, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.D.; Li, K.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Yin, Y.H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, W.D. Cloning and functional analysis of ethylene response factor gene PpcERF5 from Chinese cherry. Plant Physiol. J. 2021, 57, 59–68, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xu, J.R. Gene expression of VaERF095 and functional analysis of its promoter from Vitis amurensis. J. South. Agric. 2024, 55, 37–46, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Liu, W.; Ye, R.; Mazarei, M.; Huang, D.; Zhang, X.; Stewart, C.N. A profilin gene promoter from switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) directs strong and specific transgene expression to vascular bundles in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.Q.; Su, J.X.; Cao, X.M.; Zhu, W.; Cheng, W.H.; Zhang, W. Cloning and activity analysis of U6 promoter in Rosa chinensis old blush and Rosa multiflora. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 2651–2661, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.R.; Liu, X.H.; Xiu, Y.; Lin, S.Z. Cloning of the promoter of MATE40 gene from Prunus sibirica seeds and analysis of gene expression driven by promoter. Biotechnol. Bull. 2024, 40, 192–201, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sunkara, S.; Bhatnagar-Mathur, P.; Sharma, K.K. Isolation and functional characterization of a novel seed-specific promoter region from peanut. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 172, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washida, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Suzuki, A.; Yamanouchi, U.; Akihama, T.; Harada, K.; Takaiwa, F. Identification of cis-regulatory elements required for endosperm expression of the rice storage protein glutelin gene GluB-1. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.X.; Zhou, L.W.; Hu, L.Q.; Jiang, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.J.; Feng, S.L.; Jiao, Y.; Xu, L.; Lin, W.H. Asynchrony of ovule primordia initiation in Arabidopsis. Development 2020, 147, dev196618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lai, W.; Long, L.; Gao, W.; Xu, F.; Li, P.; Zhou, S.; Ding, Y.; Hu, H.Y. Comparative proteomic analysis identified proteins and the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway involved in the response to ABA treatment in cotton fiber development. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, D.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Y.H.; Wu, C.A.; Yang, G.D.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, C.C. Cotton GhDREB1 increases plant tolerance to low temperature and is negatively regulated by gibberellic acid. New Phytol. 2007, 176, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.W.; Fan, F.H.; Xu, G. Cloning and preliminary function analysis of Jatropha curcas JcGASA6 gene promoter. Plant Physiol. J. 2023, 59, 1321–1328, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Mei, K. Expression, purification, characterization and crystallization of Panax quinquefolius ginsenoside glycosyltransferase Pq3-O-UGT2. Protein Expr. Purif. 2024, 216, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, C.L.; Shen, F.F.; Xia, G.Q. Cloning and functional analysis of chitinase gene GbCHI from sea-island cotton (Gossypium barbadense). Hereditas 2012, 34, 240–247, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Garcia, C.M.; Finer, J.J. Identification and validation of promoters and cis-acting regulatory elements. Plant Sci. 2014, 217, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahmuradov, I.A.; Umarov, R.K.; Solovyev, V.V. TSSPlant: A new tool for prediction of plant Pol II promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Guo, T.; Xu, L.X. Promoter cloning of Dof32 gene and deletion analysis of its function region in Alfafa (Medicago truncatula). Mol. Plant Breed. 2020, 18, 6678–6684, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T. Functional Analysis of NcSUT1 Promoter and Preliminary Study on NcSUT3 Transgenesis. Ph.D. Thesis, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China, 2023. (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.W.; Yu, N.; Li, C.H.; Luo, B.; Gou, J.Y.; Wang, L.J.; Chen, X.Y. Control of plant trichome development by a cotton fiber MYB gene. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2323–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, Y.; Oka, A.; Rodrigues-Pousada, R.; Possenti, M.; Ruberti, I.; Morelli, G.; Aoyama, T. Modulation of phospholipid signaling by GLABRA2 in root-hair pattern formation. Science 2003, 300, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkonyi-Gasic, E.; Wu, R.; Wood, M.; Walton, E.F.; Hellens, R.P. Protocol: A highly sensitive RT-PCR method for detection and quantification of microRNAs. Plant Methods 2007, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, B.; Shankaranarayan, G.; Sharma, N. Selection of reference gene in Eucalyptus camaldulensis for real-time qRT-PCR. BMC Proc. 2011, 5, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgenm, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beziat, C.; Kleine-Vehn, J.; Feraru, E. Histochemical staining of beta-glucuronidase and its spatial quantification. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1497, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Henriques, R.; Lin, S.S.; Niu, Q.W.; Chua, N.H. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, X.; Huang, S.; Lin, Y. Functional Characterization of a Root-Preferential and Stress-Inducible Promoter of Eca-miR482f in Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Plants 2026, 15, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010067

Zhang W, Zhou Q, Wu X, Huang S, Lin Y. Functional Characterization of a Root-Preferential and Stress-Inducible Promoter of Eca-miR482f in Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Plants. 2026; 15(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Weihua, Qian Zhou, Xiaotong Wu, Shuyi Huang, and Yuanzhen Lin. 2026. "Functional Characterization of a Root-Preferential and Stress-Inducible Promoter of Eca-miR482f in Eucalyptus camaldulensis" Plants 15, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010067

APA StyleZhang, W., Zhou, Q., Wu, X., Huang, S., & Lin, Y. (2026). Functional Characterization of a Root-Preferential and Stress-Inducible Promoter of Eca-miR482f in Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Plants, 15(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010067