Effects of Calcium and Magnesium Fertilization on the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Assembly and Specific Biomarkers in Rainfed Maize

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.1.1. Study Site

2.1.2. Experimental Design Scheme

2.1.3. Field Management

2.1.4. Pest, Disease, and Weed Management

2.2. Specific Measurements and Methods

2.2.1. Sample Pretreatment

2.2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

2.2.3. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.2.4. Soil Physicochemical Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

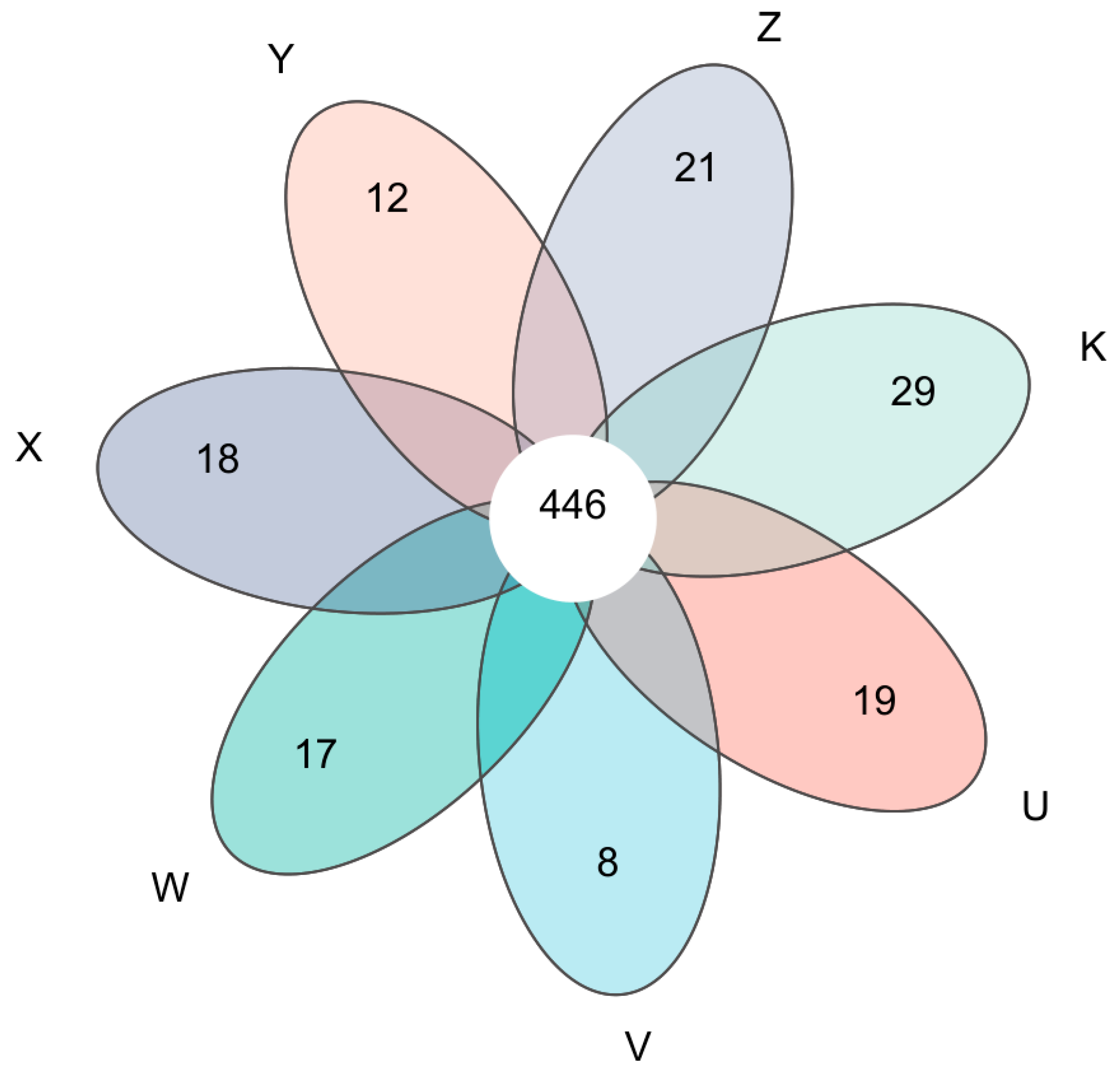

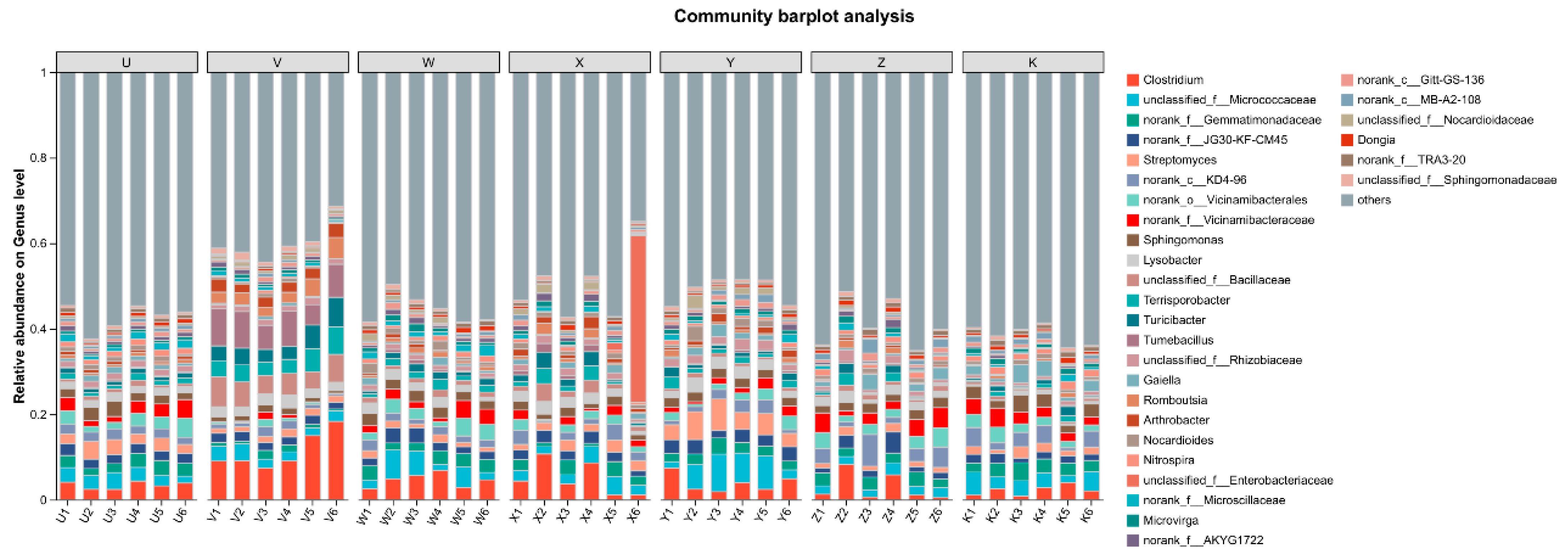

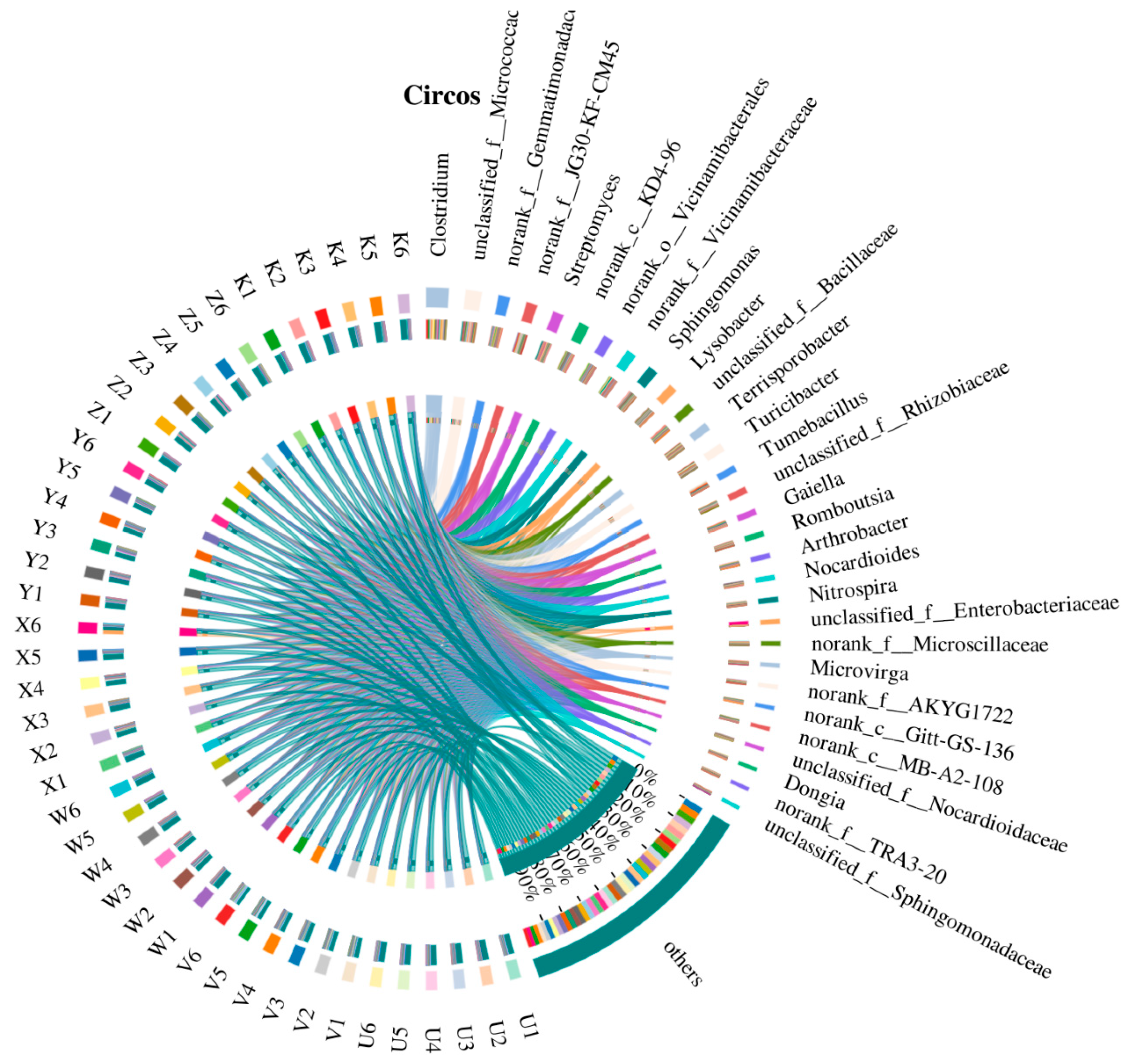

3.1. Characteristics of Soil Bacterial Community Composition

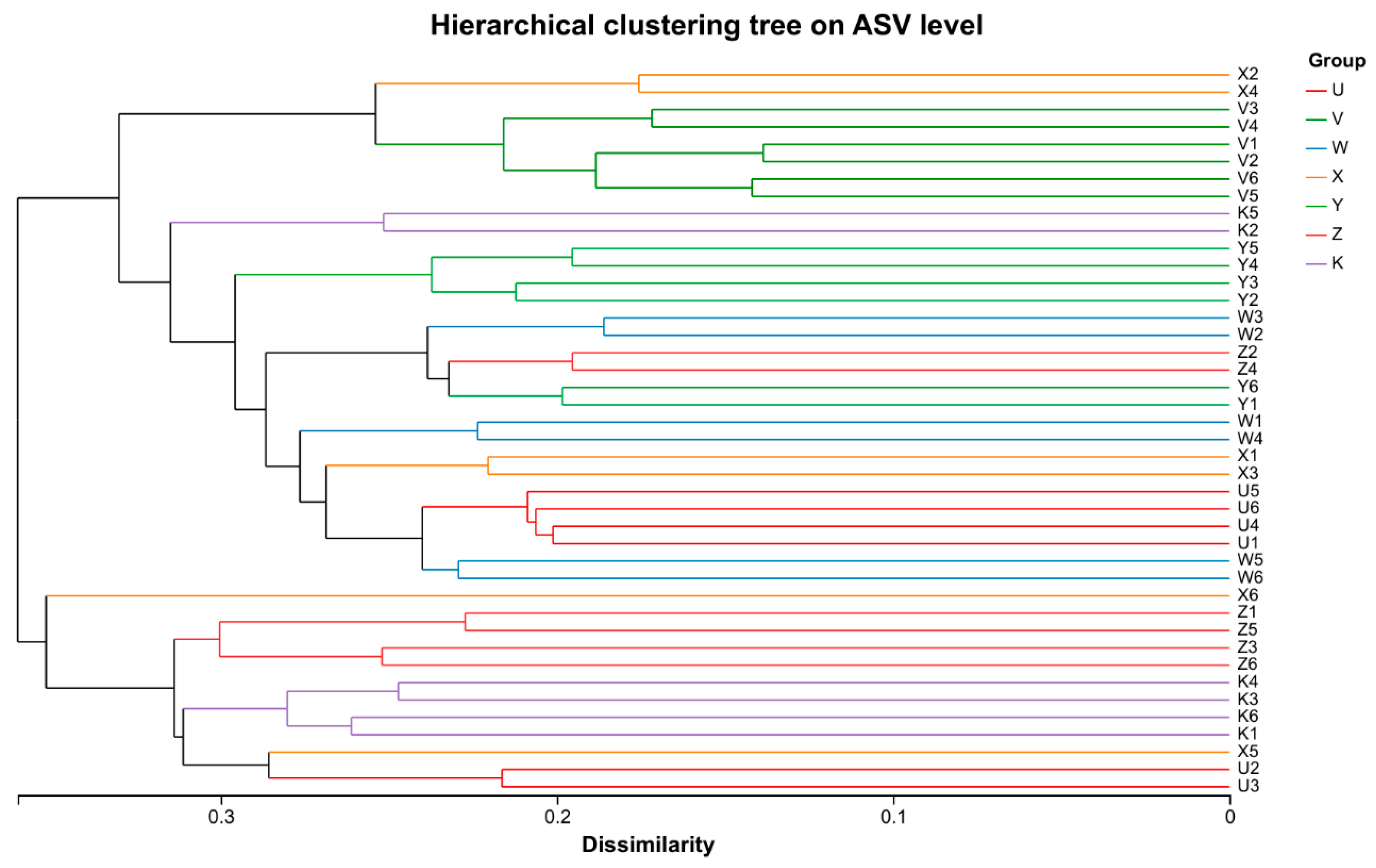

3.2. Characteristics of Soil Bacterial Community Diversity

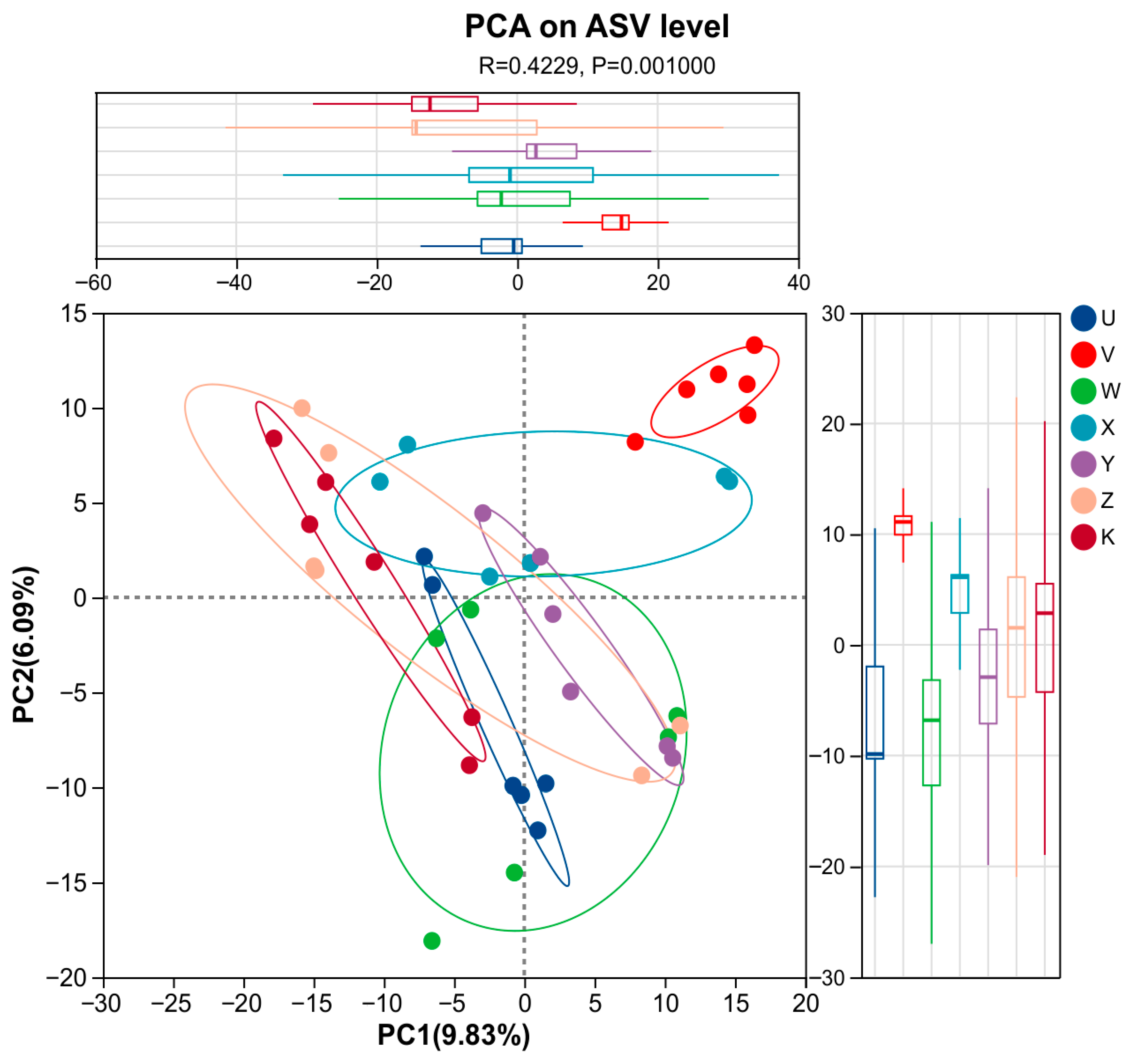

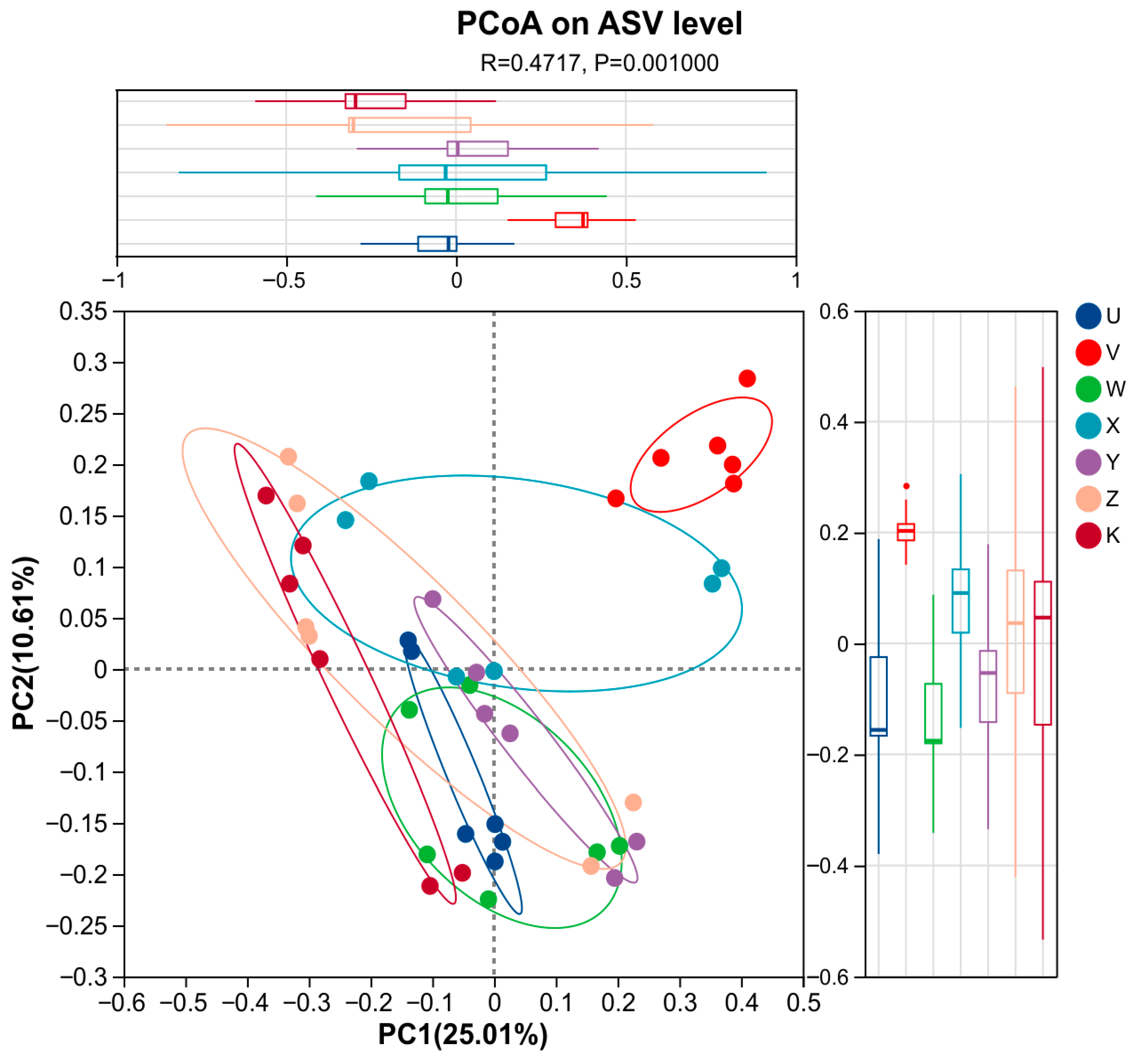

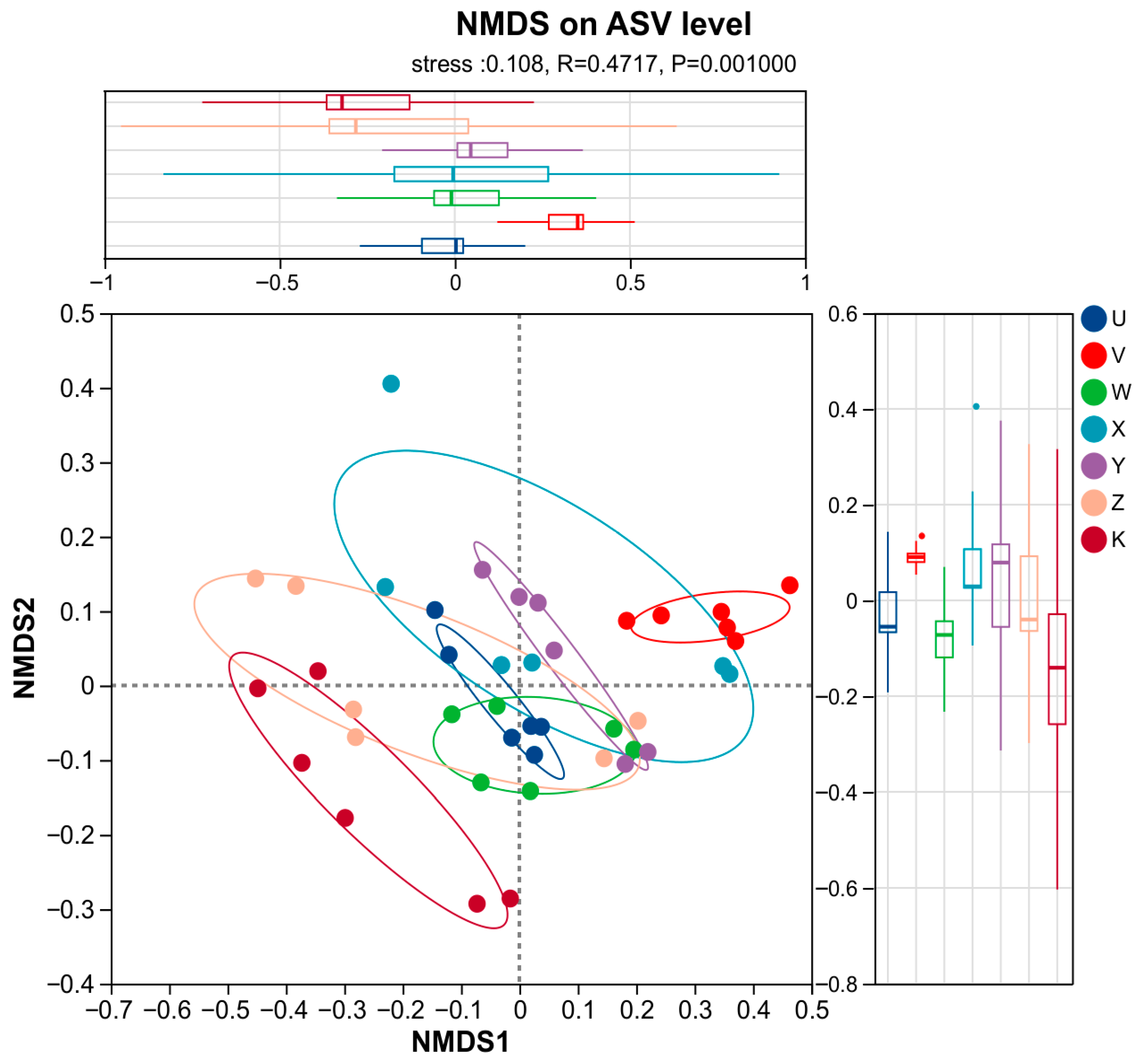

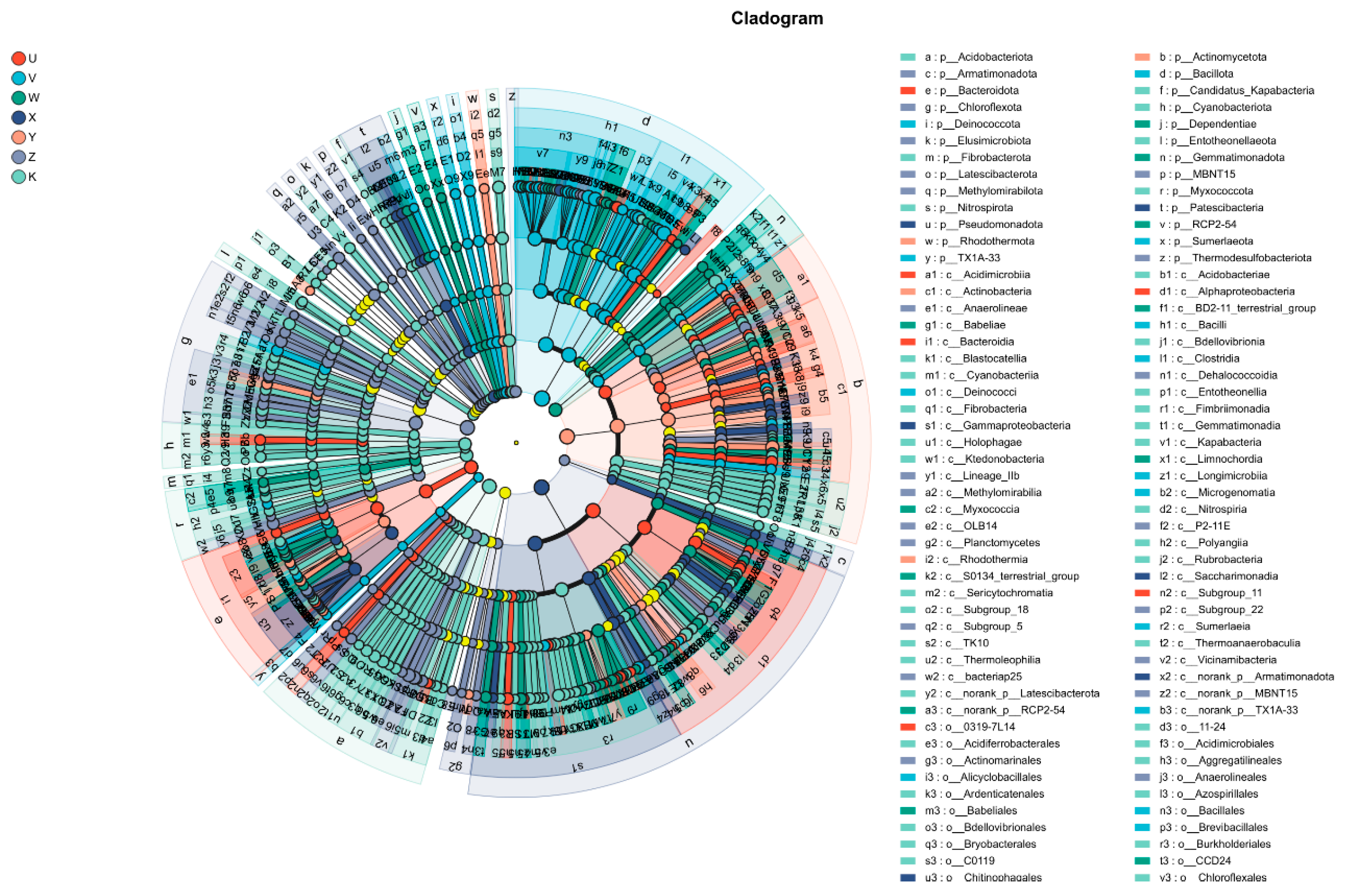

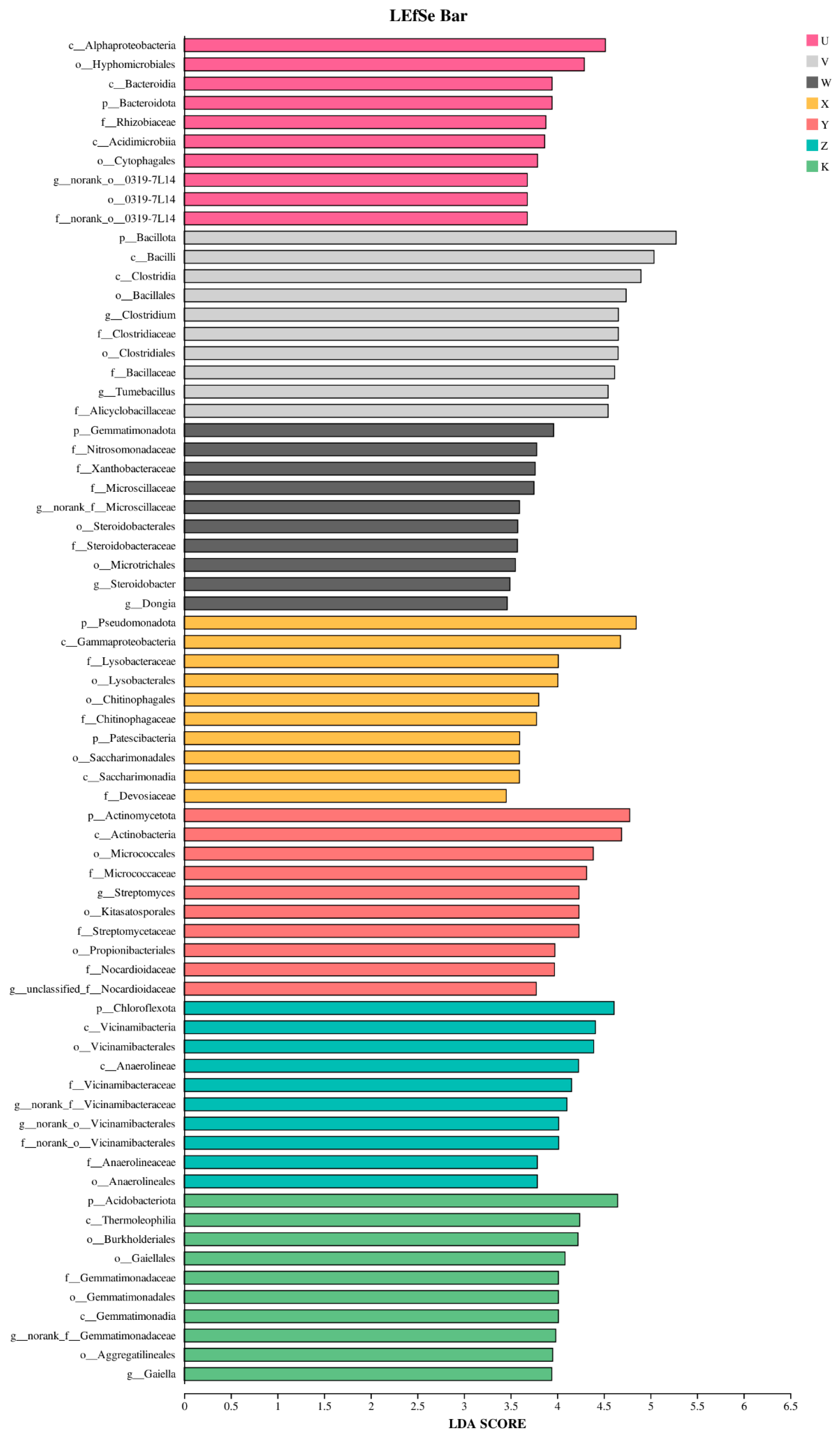

3.3. Characteristics of Soil Bacterial Community Species Differentiation

3.4. Soil Physicochemical Properties in Response to Ca and Mg Addition

4. Discussion

4.1. Ca and Mg Supplementation as Key Regulators Reshape Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Structure

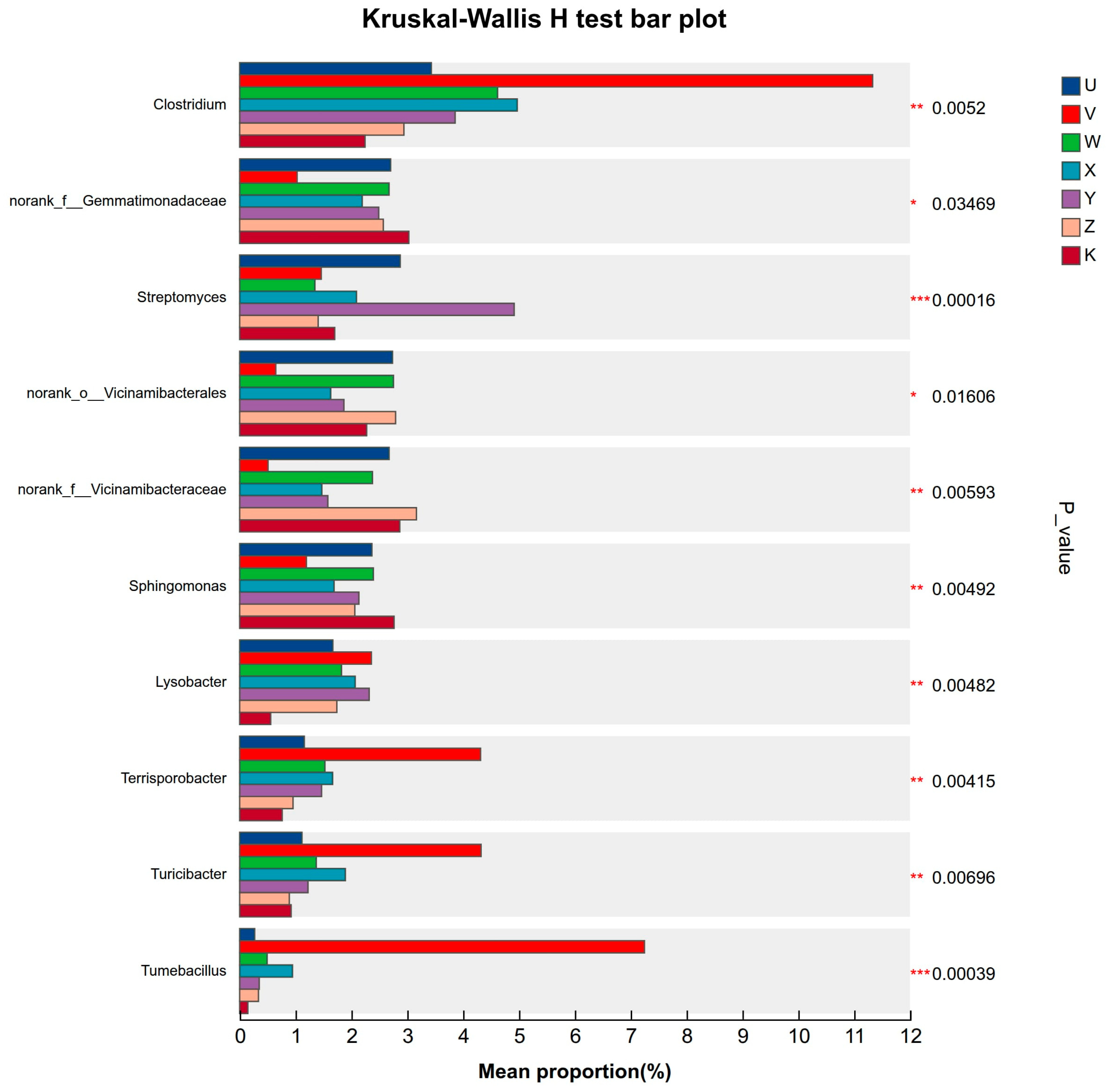

4.2. Specific Responses of Key Taxa Reveal Potential Microbial Ecological Functions

4.3. Complexity of Ca-Mg Interactions Highlights Limitations of Single-Nutrient Studies

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Calcium and magnesium supplementation served as key environmental drivers of rhizosphere bacterial community differentiation. This study confirmed that inputs of Ca and Mg at different levels and combinations created potent environmental filtering pressures by altering the rhizosphere microenvironment, leading to significant and specific restructuring of the bacterial community structure. The community response was primarily reflected in beta-diversity.

- (2)

- Different treatments enriched specific key bacterial taxa, which can serve as potential biomarkers. Through multi-treatment comparisons and LEfSe analysis, we identified treatment-specific “microbial fingerprints,” such as the enrichment of Clostridium under high Ca treatment and Lysobacter under high Mg treatment. The enrichment of these key taxa indicates potential shifts in specific ecological functions guided by Ca and Mg supplementation, such as enhanced potential for anaerobic organic matter decomposition or disease suppression. This provides concrete targets for fostering beneficial rhizosphere microbiota through targeted nutrient management.

- (3)

- Complex interactions existed between calcium and magnesium, and their combined effects were not simply additive. The combined Ca-Mg treatments resulted in unique community compositions that were not merely the sum of their individual effects. This finding underscores the necessity to shift from an isolated perspective to an integrated one in future soil nutrient management and microbial ecology research, fully accounting for nutrient synergism and antagonism.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| U | Low Ca |

| V | High Ca |

| W | Low Mg |

| X | High Mg |

| Y | Low Ca & Low Mg |

| Z | High Ca & High Mg |

| K | No Ca and No Mg |

References

- Bargaz, A.; Lyamlouli, K.; Chtouki, M.; Zeroual, Y.; Dhiba, D. Soil microbial resources for improving fertilizers efficiency in an integrated plant nutrient management system. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Singh, K.; Nagpure, G.; Mansoori, A.; Singh, R.; Ghazi, I.; Kumar, A.; Singh, J. Plant-soil-microbes: A tripartite interaction for nutrient acquisition and better plant growth for sustainable agricultural practices. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, F.; Li, Q.; Solanki, M.; Wang, Z.; Xing, Y.; Dong, D. Soil phosphorus transformation and plant uptake driven by phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1383813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Yuan, M.; Tang, L.; Shen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Li, S. Integrated microbiology and metabolomics analysis reveal responses of soil microorganisms and metabolic functions to phosphorus fertilizer on semiarid farm. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thepbandit, W.; Athinuwat, D. Rhizosphere Microorganisms supply availability of soil nutrients and induce plant defense. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Yin, J.; Huang, S. Bacterial community structure after long-term organic and inorganic fertilization reveals important associations between soil nutrients and specific taxa involved in nutrient transformations. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etesami, H.; Jeong, B.; Glick, B. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, phosphate–solubilizing bacteria, and silicon to P uptake by plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, M.; Roiloa, S.; Yu, F. Potential roles of soil microorganisms in regulating the effect of soil nutrient heterogeneity on plant performance. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Zhao, C.; Wang, E.; Raza, A.; Yin, C. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens as an excellent agent for biofertilizer and biocontrol in agriculture: An overview for its mechanisms. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 259, 127016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gao, Y.; Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. Community metagenomics reveals the processes of nutrient cycling regulated by microbial functions in soils with P fertilizer input. Plant Soil 2023, 499, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Sindhu, S.; Dhanker, R.; Kumari, A. Microbes-mediated sulphur cycling in soil: Impact on soil fertility, crop production and environmental sustainability. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 271, 127340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, X.; An, X.; Li, L.; Lin, C.; Li, H.; Li, H. Enhancement of beneficial microbiomes in plant–soil continuums through organic fertilization: Insights into the composition and multifunctionality. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2024, 6, 230223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C.; Oz, M.; Demirer, G. Engineering plant-microbe communication for plant nutrient use efficiency. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 88, 103150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Liu, W.; Huang, H.; Ye, Q.; Zhu, S.; Peng, Z.; Li, Y.; Deng, L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, H.; et al. Meta-Analysis of organic fertilization effects on soil bacterial diversity and community composition in agroecosystems. Plants 2023, 12, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, H.; He, X.; Thomas, B.; Lupwayi, N.; Hao, X.; Thomas, M.; Shi, X. Fertilization shapes bacterial community structure by alteration of soil pH. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soman, C.; Li, D.; Wander, M.; Kent, A. Long-term fertilizer and crop-rotation treatments differentially affect soil bacterial community structure. Plant Soil 2017, 413, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, T. Characteristics of the soil microbial community structure under long-term chemical fertilizer application in yellow soil paddy fields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhu, R.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Ai, C.; He, P.; Liang, G.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, P. Effect of high soil C/N ratio and nitrogen limitation caused by the long-term combined organic-inorganic fertilization on the soil microbial community structure and its dominated SOC decomposition. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 303, 114155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Yadav, P.; Sharma, S.; Maurya, P. Comparison of microbial diversity and community structure in soils managed with organic and chemical fertilization strategies using amplicon sequencing of 16S and ITS regions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1444903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, C. Effect of planting salt-tolerant legumes on coastal saline soil nutrient availability and microbial communities. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Guan, D.; Jiang, X.; Fan, F.; Meng, F.; Li, L.; Zhao, B.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, F.; Chen, H.; et al. Long-term fertilization coupled with rhizobium inoculation promotes soybean yield and alters soil bacterial community composition. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1161983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Q.; Du, B.; Chen, W.; Wei, D.; Huang, Q. Contrasting responses of bacterial and fungal communities to aggregate-size fractions and long-term fertilizations in soils of northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Khan, A.; Li, K.; Xu, X.; Adnan, M.; Fahad, S.; Ahmad, R.; Khan, M.; Nawaz, T.; Zaman, F. Influences of long-term crop cultivation and fertilizer management on soil aggregates stability and fertility in the Loess Plateau, northern China. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nut. 2022, 22, 1446–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Naseer, M.; Che, Y.; Dai, Y.; Luo, X.; Liu, D.; Song, L.; et al. Magnesium Fertilization Affected Rice Yields in Magnesium Sufficient Soil in Heilongjiang Province, Northeast China. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 645806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Xia, Q.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Yang, Z. Rhizosphere soil properties, microbial community, and enzyme activities: Short-term responses to partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic manure. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, M.; Wang, Y.; Yan, M.; Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; Li, C.; Li, X. Physiological Essence of Magnesium in Plants and Its Widespread Deficiency in the Farming System of China. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 802274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Su, C.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y. Evaluating the soil quality of newly created farmland in the hilly and gully region on the Loess Plateau, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kour, D.; Kaur, T.; Devi, R.; Yadav, A.; Dikilitas, M.; Abdel-Azeem, A.; Ahluwalia, A.; Saxena, A. Biodiversity, and biotechnological contribution of beneficial soil microbiomes for nutrient cycling, plant growth improvement and nutrient uptake. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 33, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Qin, H.; Wang, J.; Yao, D.; Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Zhu, B. Immediate response of paddy soil microbial community and structure to moisture changes and nitrogen fertilizer application. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1130298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eo, J.; Park, K. Long-term effects of imbalanced fertilization on the composition and diversity of soil bacterial community. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 231, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Si, H.; He, J.; Fan, L.; Li, L. The shifts of maize soil microbial community and networks are related to soil properties under different organic fertilizers. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megyes, M.; Borsodi, A.; Árendás, T.; Márialigeti, K. Variations in the diversity of soil bacterial and archaeal communities in response to different long-term fertilization regimes in maize fields. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Deng, S.; Raun, W.; Wang, Y.; Teng, Y. Bacterial community in soils following century-long application of organic or inorganic fertilizers under continuous winter wheat cultivation. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Niu, X.; Chen, B.; Pu, S.; Li, P.; Feng, G. Chemical fertilizer reduction combined with organic fertilizer affects the soil microbial community and diversity and yield of cotton. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1295722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francioli, C.; Gong, X.; Dang, K.; Li, J.; Yang, P.; Gao, X.; Deng, X.; Feng, B. Linkages between nutrient ratio and the microbial community in rhizosphere soil following fertilizer management. Environ. Res. 2020, 184, 109261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, W.; Zhu, C.; Luo, G.; Kong, Y.; Ling, N.; Wang, M.; Dai, J.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. Bacterial rather than fungal community composition is associated with microbial activities and nutrient-use efficiencies in a paddy soil with short-term organic amendments. Plant Soil 2018, 424, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, M.; Qin, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, Q.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z.; Shen, Q. Microbial communities of an arable soil treated for 8 years with organic and inorganic fertilizers. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2016, 52, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Sheaffer, C.; Wyse, D.; Staley, C.; Gould, T.; Sadowsky, M. Structure of bacterial communities in soil following cover crop and organic fertilizer incorporation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9331–9341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; Yang, X. Understanding the responses of soil bacterial communities to long-term fertilization regimes using DNA and RNA sequencing. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, W.; Li, J.; Yu, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Tan, W.; Mi, W. Short-term effect of manure and straw application on bacterial and fungal community compositions and abundances in an acidic paddy soil. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 3057–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Di, H.; He, X.; Sun, Y.; Xiang, S.; Huang, Z. The mechanism of microbial community succession and microbial co-occurrence network in soil with compost application. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 167409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, G.; Mazarji, M.; Delaplace, P.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J. Heavy metals drive microbial community assembly process in farmland with long-term biosolids application. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Lv, J.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, S. Linking soil nutrients, microbial community composition, and enzyme activities to saponin content of Paris polyphylla after addition of biochar and organic fertiliser. Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francioli, D.; Schulz, E.; Buscot, F.; Reitz, T. Dynamics of soil bacterial communities over a vegetation season relate to both soil nutrient status and plant growth phenology. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 75, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Chen, K.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, P.; Yang, J.; Han, X. Long-term fertilization altered microbial community structure in an aeolian sandy soil in northeast China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 979759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, K.; Zheng, W.; Maddela, N.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Tawfik, A.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z. Metagenomics and network analysis decipher profiles and co-occurrence patterns of bacterial taxa in soils amended with biogas slurry. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 162911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Henriksen, T.; Svensson, K.; Korsaeth, A. Long-term effects of agricultural production systems on structure and function of the soil microbial community. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, L.; Xiang, D.; Na, X.; Qiao, Z. Effect of different fertilizers on the bacterial community diversity in rhizospheric soil of broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum L.). Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2020, 68, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlatter, D.; Bakker, M.; Bradeen, J.; Kinkel, L. Plant community richness and microbial interactions structure bacterial communities in soil. Ecology 2015, 96, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, A.; Chen, S.; He, X.; Jin, L.; Yu, X.; Yang, S.; Li, B.; Fan, L.; Ji, L.; et al. Heavy metals, antibiotics and nutrients affect the bacterial community and resistance genes in chicken manure composting and fertilized soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 257, 109980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Kong, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, T.; Chen, M.; Zhu, L.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, C.; et al. Rhizosphere microbial community enrichment processes in healthy and diseased plants: Implications of soil properties on biomarkers. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1333076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | pH (H2O) | Exchangeable Ca2+ (cmol(+)∙kg−1) | Exchangeable Mg2+ (cmol(+)∙kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| K (Control) | 8.52 ± 0.04 ab | 4.85 ± 0.21 c | 1.25 ± 0.08 c |

| U (Low Ca) | 8.55 ± 0.03 ab | 5.92 ± 0.18 b | 1.28 ± 0.09 c |

| V (High Ca) | 8.59 ± 0.05 a | 7.41 ± 0.32 a | 1.31 ± 0.11 c |

| W (Low Mg) | 8.50 ± 0.04 b | 4.91 ± 0.25 c | 1.87 ± 0.14 b |

| X (High Mg) | 8.51 ± 0.03 ab | 4.99 ± 0.19 c | 2.65 ± 0.19 a |

| Y (Low Ca & Low Mg) | 8.53 ± 0.04 ab | 5.88 ± 0.22 b | 1.90 ± 0.12 b |

| Z (High Ca & High Mg) | 8.57 ± 0.04 a | 7.35 ± 0.28 a | 2.58 ± 0.17 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, Z.; Shang, X.; Jin, X. Effects of Calcium and Magnesium Fertilization on the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Assembly and Specific Biomarkers in Rainfed Maize. Plants 2026, 15, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010060

He Z, Shang X, Jin X. Effects of Calcium and Magnesium Fertilization on the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Assembly and Specific Biomarkers in Rainfed Maize. Plants. 2026; 15(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhaoquan, Xue Shang, and Xiaoze Jin. 2026. "Effects of Calcium and Magnesium Fertilization on the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Assembly and Specific Biomarkers in Rainfed Maize" Plants 15, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010060

APA StyleHe, Z., Shang, X., & Jin, X. (2026). Effects of Calcium and Magnesium Fertilization on the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Assembly and Specific Biomarkers in Rainfed Maize. Plants, 15(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010060