Influence of β-Cyclodextrin on the Overall Antioxidant Activity and DPPH· Reaction Kinetics of Fresh Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) and Dehydrated Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Extracts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

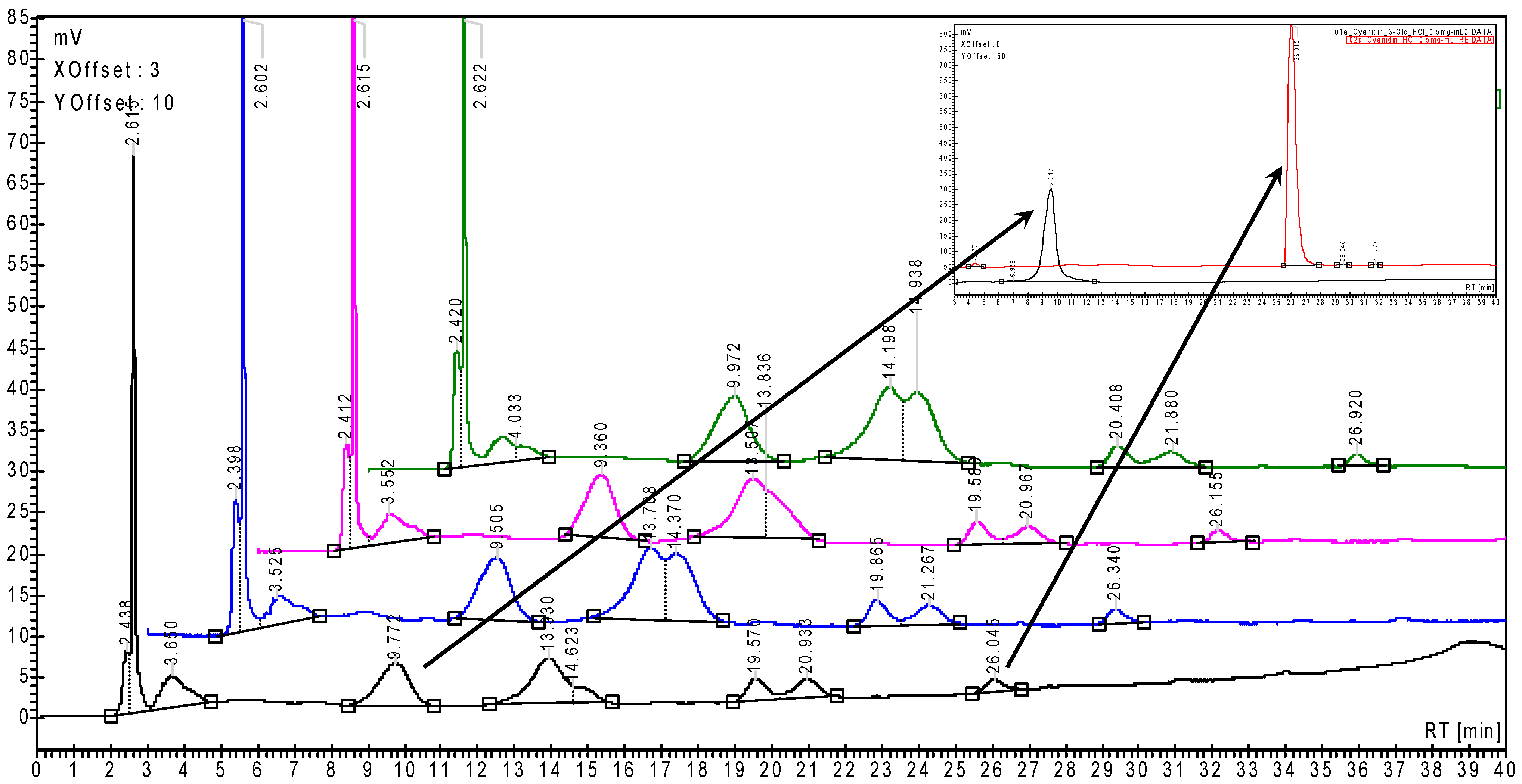

2.1. Obtaining the Berry Extracts and Quantification of Anthocyanins

n = 6, r = 0.9990, r2 = 0.9981, F = 2589, p < 10−5, s = 0.015

n = 7, r = 0.9997, r2 = 0.9994, F = 9246, p < 10−5, s = 0.008

2.2. Dehydration of Strawberry Slices with or Without β-Cyclodextrin as an Additive

2.3. Antioxidant Activity of the Berry Extracts from the Raw and Dehydrated Fruits

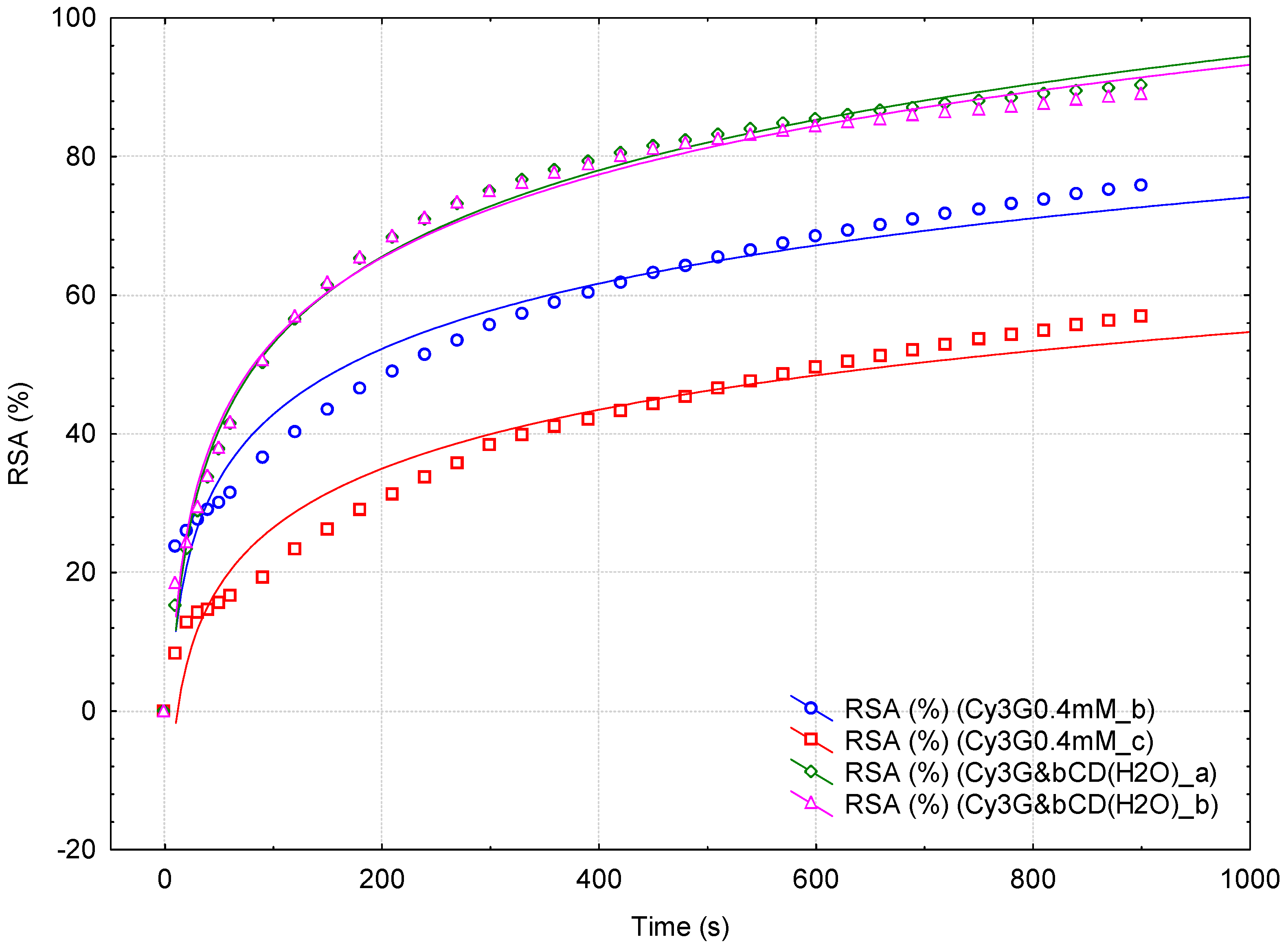

2.4. Kinetics of the DPPH· Reaction with Antioxidant Compounds in Berry Extracts with or Without β-Cyclodextrin as an Additive

3. Discussion

3.1. Identification and Quantification of Anthocyanins

3.2. Dehydration of Strawberry Fruits

3.3. Antioxidant Activity of Berry Extracts

3.4. Kinetic Studies

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Chemicals

4.2. Dehydration of Fruits in the Presence or Absence of β-Cyclodextrin

4.3. Extraction of Antioxidants from Fresh and Dehydrated Fruits

4.4. HPLC Analysis of the Main Anthocyanins from Fruits

4.5. Radical Scavenging Activity of Fruit Extracts

4.6. DPPH· Reaction Kinetics in the Presence of Fruit Extracts and Standard Anthocyanins

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α-CD | α-Cyclodextrin |

| Abs | Absorbance (in UV-Vis spectrophotometry) |

| ABTS+· | 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation |

| AP | Antioxidant power |

| ASA | Acetylsalicylic acid |

| β-CD | β-Cyclodextrin |

| CD | Cyclodextrin |

| Cy3G | Cyanidin 3-O-glucopyranoside |

| DPPH· | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical |

| dw | dry weight |

| EC50 | Half maximal effective concentration |

| F | Fisher-value (Fisher-test) |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| γ-CD | γ-Cyclodextrin |

| GRAS | Generally recognized as safe |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HSD | Honestly significant difference (Tukey’s HSD test) |

| kn | Reaction rate constant for the nth order kinetic model |

| HPLC | High pressure liquid chromatography |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LogP | Logarithm of the 1-octanol/water partition coefficient |

| LOQ | Limit of quantitation |

| M | Molar concentration, mol/L |

| mM | milimolar concentration, mmol/L |

| NaDES | Natural deep eutectic solvent |

| ORAC | Oxygen radical absorbance capacity |

| p-value | probability (null-hypothesis significance test) |

| PEF | Pulsed electric field |

| Plg3G | Pelargonidin 3-O-glucopyranoside |

| QSAR | Quantitative structure-activity relationship |

| r/r2 | Correlation/determination coefficient |

| RB | Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) |

| RP-HPLC | Reversed phase—high pressure liquid chromatography |

| RSA | Radical scavenging activity |

| RT | Retention time |

| s | standard error of estimate |

| SB | Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| t1/2(n) | Half-time for the nth order kinetic model |

| TAC | Total anthocyanin content |

| TE | Trolox equivalent |

| TEAC | Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry |

References

- Neha, K.; Haider, M.R.; Pathak, A.; Yar, M.S. Medicinal prospects of antioxidants: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 178, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, D.M.; Maan, S.A.; Baker, D.H.A.; Abozed, S.S. In vitro assessments of antioxidant, antimicrobial, cytotoxicity and anti-inflammatory characteristics of flavonoid fractions from flavedo and albedo orange peel as novel food additives. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Batool, A.; Yaqub, S.; Iqbal, A.; Kauser, S.; Arif, M.R.; Ali, S.; Gorsi, F.I.; Nisar, R.; Hussain, A.; et al. Effects of spray drying and ultrasonic assisted extraction on the phytochemicals, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of strawberry fruit. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.K.d.S.; Costa-Orlandi, C.B.; Fernandes, M.A.; Brasil, G.S.A.P.; Mussagy, C.U.; Scontri, M.; Sasaki, J.C.d.S.; Abreu, A.P.d.S.; Guerra, N.B.; Floriano, J.F.; et al. Biocompatible anti-aging face mask prepared with curcumin and natural rubber with antioxidant properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyenihi, A.B.; Smith, C. Are polyphenol antioxidants at the root of medicinal plant anti-cancer success? J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 229, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Meckling, K.A.; Marcone, M.F.; Kakuda, Y.; Tsao, R. Can phytochemical antioxidant rich foods act as anti-cancer agents? Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2545–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.-Y.; Jin, M.-Z.; Chen, J.-F.; Zhou, H.-H.; Jin, W.-L. Live or let die: Neuroprotective and anti-cancer effects of nutraceutical antioxidants. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 183, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, H. Role of antioxidants in the skin: Anti-aging effects. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2010, 58, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A. Mechanisms of antidiabetic effects of flavonoid rutin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmie, M.; Bester, M.J.; Serem, J.C.; Nell, M.; Apostolides, Z. The potential antidiabetic properties of green and purple tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O Kuntze], purple tea ellagitannins, and urolithins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 309, 116377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Cottrell, J.J.; Dunshea, F.R. Identification and characterization of anthocyanins and non-anthocyanin phenolics from Australian native fruits and their antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-Alzheimer potential. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 111951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Bao, J.; Liang, P.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Hu, F. Extraction of flavonoids and phenolic acids from poplar-type propolis: Optimization of maceration process, evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 233, 118481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Pan, Y.; Yang, W.; Yang, B.; Ou, S.; Liu, P.; Zheng, J. Hepatoprotective effect of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside–lauric acid ester against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in LO2 cells. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 107, 105642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwambale, W.; Oka, V.O.; Etukudo, E.M.; Owu, D.U.; Nkanu, E.E.; Okon, I.A.; Emmanuel, S.D.; Shehu, U.U.; Wilber, N.; Kambere, A.; et al. Nephroprotective activity of naringenin in gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in male Wistar rats: In-vivo and in-silico evaluation. Pharmacol. Res.—Nat. Prod. 2025, 9, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Busi, M.; Arredondo, F.; González, D.; Echeverry, C.; Vega-Teijido, M.A.; Carvalho, D.; Rodríguez-Haralambides, A.; Rivera, F.; Dajas, F.; Abin-Carriquiry, J.A. Purification, structural elucidation, antioxidant capacity and neuroprotective potential of the main polyphenolic compounds contained in Achyrocline satureioides (Lam) D.C. (Compositae). Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 2579–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, M.J.; Davies, N.; Myburgh, K.H.; Lecour, S. Proanthocyanidins, anthocyanins and cardiovascular diseases. Food Res. Int. 2014, 59, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladěnka, P.; Zatloukalová, L.; Filipský, T.; Hrdina, R. Cardiovascular effects of flavonoids are not caused only by direct antioxidant activity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, G.A.B.; Oliveira, D.R.; da-Conceição, L.S.M.; Farah, J.P.S.; Tavares, M.F.M. Development and validation of a liquid chromatography method for anthocyanins in strawberry (Fragaria spp.) and complementary studies on stability, kinetics and antioxidant power. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, V.C.; Calvete, E.; Reginatto, F.H. Quality properties and antioxidant activity of seven strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa duch) cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhanfezova, T.; Barba-Espín, G.; Müller, R.; Joernsgaard, B.; Hegelund, J.N.; Madsen, B.; Larsen, D.H.; Vega, M.M.; Toldam-Andersen, T.B. Anthocyanin profile, antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of a strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch) genetic resource collection. Food Biosci. 2020, 36, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, A.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Fecka, I. Comparison of polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity of strawberry fruit from 90 cultivars of Fragaria × ananassa Duch. Food Chem. 2019, 270, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, D.I.; Hădărugă, N.G. Flavonols. Chemistry, Functionality, and Applications. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients: Properties and Applications; Jafari, S.M., Rashidinejad, A., Simal-Gandara, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 159–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, N.G.; Hădărugă, D.I. Hydroxycinnamic acids. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients: Properties and Applications; Jafari, S.M., Rashidinejad, A., Simal-Gandara, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobinaitė, R.; Viškelis, P.; Venskutonis, P.R. Nutritional Composition of Fruit Cultivars. In Nutritional Composition of Fruit Cultivars; Simmonds, M.S.J., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de-Souza, V.R.; Pereira, P.A.P.; da-Silva, T.L.T.; Lima, L.C.d.O.; Pio, R.; Queiroz, F. Determination of the bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and chemical composition of Brazilian blackberry, red raspberry, strawberry, blueberry and sweet cherry fruits. Food Chem. 2014, 156, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobek, M.; Cybulska, J.; Zdunek, A.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Frąc, M. Effect of microbial biostimulants on the antioxidant profile, antioxidant capacity and activity of enzymes influencing the quality level of raspberries (Rubus idaeus L.). Food Chem. 2024, 454, 139746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, N.K. Strawberries and Raspberries. In Handbook of Fruits and Fruit Processing; Sinha, N.K., Sidhu, J.S., Barta, J., Wu, J.S.B., Cano, M.P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2012; pp. 419–431. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Wang, L.; Yin, W.; Liang, J. Antioxidant activity and subcritical water extraction of anthocyanin from raspberry process optimization by response surface methodology. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de-Souza, V.B.; Fujita, A.; Thomazini, M.; da-Silva, E.R.; Francisco Lucon, J., Jr.; Genovese, M.I.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S. Functional properties and stability of spray-dried pigments from Bordo grape (Vitis labrusca) winemaking pomace. Food Chem. 2014, 164, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krgović, N.; Jovanović, M.S.; Nedeljković, S.K.; Šavikin, K.; Lješković, N.J.; Ilić, M.; Živković, J.; Menković, N. Natural deep eutectic solvents extraction of anthocyanins—Effective method for valorisation of black raspberry (Rubus occidentalis L.) pomace. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 223, 120237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos-Llano, K.R.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R. Effect of pulsed light treatments on quality and antioxidant properties of fresh-cut strawberries. Food Chem. 2018, 264, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucan-(Banciu), C.A.; Cugerean, M.I.; Gălan, I.M.; Ciobanu-(Şibu), A.; Pop-(Mateuţ), A.; Oprinescu, C.I.; Drăghici, L.R.; Hădărugă, D.I.; Hădărugă, N.G. State-of-the-art on the Dehydration and Drying of Cucurbita Species. Bull. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 81, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asioli, D.; Rocha, C.; Wongprawmas, R.; Popa, M.; Gogus, F.; Almli, V.L. Microwave-dried or air-dried? Consumers’ stated preferences and attitudes for organic dried strawberries. A multi-country investigation in Europe. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amami, E.; Khezami, W.; Mezrigui, S.; Badwaik, L.S.; Bejar, A.K.; Perez, C.T.; Kechaou, N. Effect of ultrasound-assisted osmotic dehydration pretreatment on the convective drying of strawberry. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2017, 36, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de-Bruijn, J.; Bórquez, R. Quality retention in strawberries dried by emerging dehydration methods. Food Res. Int. 2014, 63, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, C.; Martín-Esparza, M.E.; Chiralt, A.; Martínez-Navarrete, N. Influence of microwave application on convective drying: Effects on drying kinetics, and optical and mechanical properties of apple and strawberry. J. Food Eng. 2008, 88, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Simpson, R.; Pizarro, N.; Parada, K.; Pinilla, N.; Reyes, J.E.; Almonacid, S. Effect of ohmic heating and vacuum impregnation on the quality and microbial stability of osmotically dehydrated strawberries (cv. Camarosa). J. Food Eng. 2012, 110, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, N.; Heybeli, N.; Ertekin, C. Infrared drying of strawberry. Food Chem. 2017, 219, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, A.S.; Çetinbaş, A.; Karakaya, H. Analysis of strawberry drying behavior under a solar chimney collector using a full factorial method. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 73, 106614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doymaz, İ. Convective drying kinetics of strawberry. Chem. Eng. Process. 2008, 47, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagy, A.; Gamea, G.R.; Essa, A.H.A. Solar drying characteristics of strawberry. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.-L.; Wang, Q.-H.; Huang, C.; Sutar, P.P.; Lin, Y.-W.; Okaiyeto, S.A.; Lin, Z.-F.; Wu, Y.-T.; Ma, W.-M.; Xiao, H.-W. Effect of various different pretreatment methods on infrared combined hot air impingement drying behavior and physicochemical properties of strawberry slices. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambon, A.; Zulli, R.; Boldrin, F.; Spilimbergo, S. Microbial inactivation and drying of strawberry slices by supercritical CO2. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2022, 180, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, S.J.; Pawłowski, A.; Szadzińska, J.; Łechtańska, J.; Stasiak, M. High power airborne ultrasound assist in combined drying of raspberries. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 34, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Tian, B. Chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol film loading β-acids/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex: A shelf-life extension strategy for strawberry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 312, 144223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Li, S.; Gao, Q. Development of an antibacterial hydrogel by κ-carrageenan with carvacrol/hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin composite and its application for strawberry preservation. Food Control 2025, 171, 111100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, I.; Rosa, E.; Heredia, A.; Escriche, I.; Andrés, A. Influence of storage on the volatile profile, mechanical, optical properties and antioxidant activity of strawberry spreads made with isomaltulose. Food Biosci. 2016, 14, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, S.; Deng, L.; Zhao, L.; Gao, S.; Fu, Y.; Ye, F. Nerolidol/hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin inclusion complex nanofibers: Active food packaging for effective strawberry preservation. Food Chem. X 2025, 28, 102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, B. Effect of alginate coating combined with yeast antagonist on strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) preservation quality. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 53, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-L.; Zhang, M.; Yan, W.-Q.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Sun, D.-F. Effect of coating on post-drying of freeze-dried strawberry pieces. J. Food Eng. 2009, 92, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yuan, D.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Kou, X.; Ke, Q. Pickering nanoemulsion loaded with eugenol contributed to the improvement of konjac glucomannan film performance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, A.B.; Cuevas, E.; Winterhalter, P.; Garcia-Parrilla, M.C.; Troncoso, A.M. Isolation, identification, and antioxidant activity of anthocyanin compounds in Camarosa strawberry. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Laverde, L.M.; Schebor, C.; Buera, M.d.P. Water content effect on the chromatic attributes of dehydrated strawberries during storage, as evaluated by image analysis. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 52, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bórquez, R.M.; Canales, E.R.; Redon, J.P. Osmotic dehydration of raspberries with vacuum pretreatment followed by microwave-vacuum drying. J. Food Eng. 2010, 99, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, L.; Morozova, K.; Scampicchio, M. A kinetic-based stopped-flow DPPH• method. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedare, S.B.; Singh, R.P. Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osugi, J.; Sasaki, M. Kinetic studies on free radical reactions. II. The photochemical reaction between DPPH and methylmethacrylate. Rev. Phys. Chem. Jpn. 1964, 34, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sendra, J.M.; Sentandreu, E.; Navarro, J.L. Reduction kinetics of the free stable radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH•) for determination of the antiradical activity of citrus juices. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 223, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goupy, P.; Dufour, C.; Loonis, M.; Dangles, O. Quantitative Kinetic Analysis of Hydrogen Transfer Reactions from Dietary Polyphenols to the DPPH Radical. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, M.C.; Daquino, C.; DiLabio, G.A.; Ingold, K.U. Kinetics of the Oxidation of Quercetin by 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (dpph•). Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4826–4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shojaee, M.S.; Moeenfard, M.; Farhoosh, R. Kinetics and stoichiometry of gallic acid and methyl gallate in scavenging DPPH radical as affected by the reaction solvent. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothwell, J.A.; Day, A.J.; Morgan, M.R.A. Experimental Determination of Octanol-Water Partition Coefficients of Quercetin and Related Flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4355–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, A.; Murao, H.; Ohnishi-Kameyama, M.; Yamakawa, Y.; Shoji, A.; Tagashira, M.; Kanda, T.; Shindo, H.; Shibusawa, Y. Retention behavior of oligomeric proanthocyanidins in hydrophilic interaction chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1143, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshari-Nasirkandi, A.; Alirezalu, A.; Hachesu, M.A. Effect of lemon verbena bio-extract on phytochemical and antioxidant capacity of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch. cv. Sabrina) fruit during cold storage. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 25, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.M.; Angeloni, S.; Abouelenein, D.; Acquaticci, L.; Xiao, J.; Sagratini, G.; Maggi, F.; Vittori, S.; Caprioli, G. A new HPLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of 36 polyphenols in blueberry, strawberry and their commercial products and determination of antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, M.; Lindauer, R.; Butz, P.; Tauscher, B. Effect of heat/pressure on cyanidin-3-glucoside ethanol model solutions. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2008, 121, 142003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Hu, X.; Liao, X. Spectral Alteration and Degradation of Cyanidin-3-glucoside Exposed to Pulsed Electric Field. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3524–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiyanagi, T.; Oikawa, K.; Tateyama, C.; Konishi, T. Acid Mediated Hydrolysis of Blueberry Anthocyanins. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadilova, E.; Carle, R.; Stintzing, F.C. Thermal degradation of anthocyanins and its impact on color and in vitro antioxidant capacity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, D.I.; Hădărugă, N.G. Flavanones in Plants and Humans. Chemistry, Functionality, and Applications. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients: Properties and Applications; Jafari, S.M., Rashidinejad, A., Simal-Gandara, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 223–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, N.G.; Hădărugă, D.I. Stilbenes and Its Derivatives and Glycosides. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients: Properties and Applications; Jafari, S.M., Rashidinejad, A., Simal-Gandara, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 487–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, D.I.; Hădărugă, N.G.; Bandur, G.N.; Isengard, H.-D. Water content of flavonoid/cyclodextrin nanoparticles: Relationship with the structural descriptors of biologically active compounds. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, N.G.; Bandur, G.N.; David, I.; Hădărugă, D.I. A review on thermal analyses of cyclodextrins and cyclodextrin complexes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandave, P.C.; Pawar, P.K.; Ranjekar, P.K.; Mantri, N.; Kuvalekar, A.A. Comprehensive evaluation of in vitro antioxidant activity, total phenols and chemical profiles of two commercially important strawberry varieties. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 172, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Hasan, M.N.; Khan, M.Z.H. Study on different nano fertilizers influencing the growth, proximate composition and antioxidant properties of strawberry fruits. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 6, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Ye, J.; Vanga, S.K.; Raghavan, V. Influence of high-intensity ultrasound on bioactive compounds of strawberry juice: Profiles of ascorbic acid, phenolics, antioxidant activity and microstructure. Food Control 2019, 96, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Wu, W.; Lyu, L.; Li, W. Changes in antioxidant substances and antioxidant enzyme activities in raspberry fruits at different developmental stages. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 321, 112314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Hogan, S.; Chung, H.; Welbaum, G.E.; Zhou, K. Inhibitory effect of raspberries on starch digestive enzyme and their antioxidant properties and phenolic composition. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falah, M.A.F.; Machfoedz, M.M.; Rahmatika, A.M.; Putri, R.M. Quality characterization of freeze-dried tropical strawberries pretreated through osmotic dehydration. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.C.; Almeida, R.L.J.; Monteiro, S.S.; Silva, E.T.d.V.; Silva, V.M.d.A.; André, A.M.M.C.N.; Ribeiro, V.H.d.A.; de-Brito, A.C.O. Influence of ethanol and ultrasound on drying, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant activity of strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa). J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chat, O.A.; Najar, M.H.; Dar, A.A. Evaluation of reduction kinetics of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazylradical by flavonoid glycoside Rutin in mixed solvent based micellar media. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2013, 436, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, M.C.; Slavova-Kazakov, A.; Rocco, C.; Kancheva, V.D. Kinetics of curcumin oxidation by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH˙): An interesting case of separated coupled proton–electron transfer. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 8331–8337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iordănescu, O.A.; Băla, M.; Gligor-(Pane), D.; Zippenfening, S.E.; Cugerean, M.I.; Petroman, M.I.; Hădărugă, D.I.; Hădărugă, N.G.; Riviş, M. A DPPH· Kinetic Approach on the Antioxidant Activity of Various Parts and Ripening Levels of Papaya (Carica papaya L.) Ethanolic Extracts. Plants 2021, 10, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordănescu, O.A.; Băla, M.; Iuga, A.C.; Gligor-(Pane), D.; Dascălu, I.; Bujancă, G.S.; David, I.; Hădărugă, N.G.; Hădărugă, D.I. Antioxidant activity and discrimination of organic apples (Malus domestica Borkh.) cultivated in the western region of Romania: A DPPH· kinetics–PCA approach. Plants 2021, 10, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, M.; Jabbari, A. Antioxidant potential and DPPH radical scavenging kinetics of water-insoluble flavonoid naringenin in aqueous solution of micelles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 489, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannala, A.S.; Chan, T.S.; O’Brien, P.J.; Rice-Evans, C.A. Flavonoid B-Ring Chemistry and Antioxidant Activity: Fast Reaction Kinetics. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 282, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.M.; Lissi, E.A. Kinetics of the Reaction between 2,2′-Azinobis(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid) (ABTS) Derived Radical Cations and Phenols. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1997, 29, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez, C.; Aliaga, C.; Lissi, E. Kinetics profiles in the reaction of ABTS derived radicals with simple phenols and polyphenols. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2004, 49, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Saura-Calixto, F. Anti-oxidant capacity of dietary polyphenols determined by ABTS assay: A kinetic expression of the results. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, N.-G.; Popescu, G.; Gligor-(Pane), D.; Mitroi, C.L.; Stanciu, S.M.; Hădărugă, D.I. Discrimination of β-cyclodextrin/hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) oil/flavonoid glycoside and flavonolignan ternary complexes by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy coupled with principal component analysis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2023, 19, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horablaga, A.; Şibu-(Ciobanu), A.; Megyesi, C.I.; Gligor-(Pane), D.; Bujancă, G.S.; Velciov, A.B.; Morariu, F.E.; Hădărugă, D.I.; Mişcă, C.D.; Hădărugă, N.G. Estimation of the Controlled Release of Antioxidants from β-Cyclodextrin/Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) or Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum L.), Asteraceae, Hydrophilic Extract Complexes through the Fast and Cheap Spectrophotometric Technique. Plants 2023, 12, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Yuan, Y.; Cui, L.; Wang, Z.; Yue, T. Cyclodextrin-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds: Current research and future prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 79, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, G.-J.; Sun, L.-L.; Cao, X.-X.; Li, H.-H.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.-N.; Ren, X.-L. Comprehensive evaluation of solubilization of flavonoids by various cyclodextrins using high performance liquid chromatography and chemometry. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 94, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Abellán, C.; Pérez-Abril, M.; Castillo, J.; Serrano, A.; Mercader, M.T.; Fortea, M.I.; Gabaldón, J.A.; Núñez-Delicado, E. Effect of temperature, pH, β- and HP-β-cds on the solubility and stability of flavanones: Naringenin and hesperetin. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 108, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasooriya, C.C.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Extraction of phenolic compounds from grapes and their pomace using β-cyclodextrin. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krstić, L.; Jarho, P.; Ruponen, M.; Urtti, A.; González-García, M.J.; Diebold, Y. Improved ocular delivery of quercetin and resveratrol: A comparative study between binary and ternary cyclodextrin complexes. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 624, 122028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Liu, B.; Zhao, J.; Thomas, D.S.; Hook, J.M. An investigation into the supramolecular structure, solubility, stability and antioxidant activity of rutin/cyclodextrin inclusion complex. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhoa, E.; Grootveld, M.; Soares, G.; Henriques, M. Cyclodextrins as encapsulation agents for plant bioactive compounds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Chang, M.; Shi, Z.-W.; Li, Y.-Y.; An, S.-Y.; Ren, D.-F. Encapsulation of rose anthocyanins with β-cyclodextrin for enhanced stability: Preparation, characterization, and its application in rose juice. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzinos, I.; Makris, D.P.; Yannakopoulou, K.; Kalogeropoulos, N.; Michali, I.; Karathanos, V.T. Thermal Stability of Anthocyanin Extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. in the Presence of β-Cyclodextrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 10303–10310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xu, Y.; Shishir, M.R.I.; Zheng, X.; Chen, W. Green extraction of mulberry anthocyanin with improved stability using β-cyclodextrin. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2494–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, D.V.; Fraga, S.; Antelo, F. Thermal degradation kinetics of anthocyanins extracted from juçara (Euterpe edulis Martius) and ‘‘Italia” grapes (Vitis vinifera L.), and the effect of heating on the antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.-N.; Kim, H.-J.; Chun, J.; Heo, H.J.; Kerr, W.L.; Choi, S.-G. Degradation kinetics of phenolic content and antioxidant activity of hardy kiwifruit (Actinidia arguta) puree at different storage temperatures. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 89, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ramírez, J.; Méndez-Lagunas, L.L.; López-Ortiz, A.; Muñiz-Becerá, S.; Nair, K. Solar drying of strawberry using polycarbonate with UV protection and polyethylene covers: Influence on anthocyanin and total phenolic content. Sol. Energy 2021, 221, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Lagunas, L.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, J.; Cruz-Gracida, M.; Sandoval-Torres, S.; Barriada-Bernal, G. Convective drying kinetics of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa): Effects on antioxidant activity, anthocyanins and total phenolic content. Food Chem. 2017, 230, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Lagunas, L.L.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, J.; Sandoval-Torres, S.; Barragán-Iglesias, J.; López-Ortíz, A. Strawberry fluidized bed drying. Antiadhesion pretreatments and their effect on bioactive compounds. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojiljković, D.; Arsić, I.; Tadić, V. Extracts of wild apple fruit (Malus sylvestris (L.) Mill., Rosaceae) as asource of antioxidant substances for use in production ofnutraceuticals and cosmeceuticals. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 80, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veggi, P.C.; Santos, D.T.; Meireles, M.A.A. Anthocyanin extraction from Jabuticaba (Myrciaria cauliflora) skins by different techniques: Economic evaluation. Procedia Food Sci. 2011, 1, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Kou, X.; Fugal, K.; McLaughlin, J. Comparison of HPLC Methods for Determination of Anthocyanins and Anthocyanidins in Bilberry Extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghose, A.K.; Pritchett, A.; Crippen, G.M. Atomic Physicochemical Parameters for Three Dimensional Structure Directed Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationships III: Modeling Hydrophobic Interactions. J. Comput. Chem. 1988, 9, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanadhan, V.N.; Ghose, A.K.; Reyankar, G.R.; Robins, R.K. Atomic Physicochemical Parameters for Three Dimensional Structure Directed Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationships. 4. Additional Parameters for Hydrophobic and Dispersive Interactions and Their Application for an Automated Superposition of Certain Naturally Occurring Nucleoside Antibiotics. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1989, 29, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anthocyanins and Anthocyanidins | Content (mg/100 g fw) |

|---|---|

| Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | 14.62 ± 2.64 |

| Cyanidin | 0.64 ± 0.07 |

| Total anthocyanins and anthocyanidins 1 | 73.18 ± 12.39 |

| Anthocyanins and Anthocyanidins | Content in Fresh Fruits (mg/100 g fw) | Content in β-CD-Assisted Dehydrated Fruits (mg/100 g) 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | 0.32 ± 0.08 | 0.15 |

| Pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside 2 | 2.46 ± 0.38 | 1.64 |

| Cyanidin | 0.017 ± 0.003 | 0.033 |

| Total anthocyanins and anthocyanidins 3 | 4.28 ± 0.56 | 4.30 |

| Sample Code | RSA (%) (@ ½ min) | RSA (%) (@ 3 min) | RSA (%) (@ 15 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SB | 44.84 ± 9.59 A | 67.80 ± 8.10 A | 81.17 ± 2.20 A |

| SB_d1:10 | 4.37 ± 1.31 a | 8.60 ± 1.68 a | 13.40 ± 1.54 a |

| SBD * | 81.47 A | 82.46 A | 82.53 A |

| SBD_d1:10 * | 13.04 b | 22.96 b | 35.14 b |

| SBD_bCD * | 83.98 A | 84.32 A | 84.45 A |

| SBD_bCD_d1:10 * | 19.19 c | 31.97 c | 47.32 c |

| Sample Code | RSA (%) (@ ½ min) | RSA (%) (@ 3 min) | RSA (%) (@ 15 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RB | 18.22 ± 3.67 a | 46.96 ± 2.83 a | 72.93 ± 0.99 c |

| RB_bCD | 26.15 ± 0.52 b | 55.67 ± 1.31 b | 77.41 ± 0.58 d |

| Sample Code | RSA (%) (@ ½ min) | RSA (%) (@ 3 min) | RSA (%) (@ 15 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cy3G0.4mM | 20.92 ± 9.42 a | 37.76 ± 12.41 a | 66.37 ± 13.37 c |

| Cy3G&bCD | 29.13 ± 0.49 a | 65.35 ± 0.21 b | 89.63 ± 0.90 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fiţoiu, M.; Pop, A.; Vladu, E.; Poja, R.; Toporîşte, L.-A.; Molnar, C.E.; Drugă, M.; Bujancă, G.S.; David, I.; Horablaga, A.; et al. Influence of β-Cyclodextrin on the Overall Antioxidant Activity and DPPH· Reaction Kinetics of Fresh Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) and Dehydrated Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Extracts. Plants 2026, 15, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010152

Fiţoiu M, Pop A, Vladu E, Poja R, Toporîşte L-A, Molnar CE, Drugă M, Bujancă GS, David I, Horablaga A, et al. Influence of β-Cyclodextrin on the Overall Antioxidant Activity and DPPH· Reaction Kinetics of Fresh Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) and Dehydrated Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Extracts. Plants. 2026; 15(1):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010152

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiţoiu (Voin), Marinela, Anamaria Pop (Mateuţ), Elena Vladu, Roxana Poja, Lavinia-Alexandra Toporîşte, Carina Elena Molnar, Mărioara Drugă, Gabriel Stelian Bujancă, Ioan David, Adina Horablaga, and et al. 2026. "Influence of β-Cyclodextrin on the Overall Antioxidant Activity and DPPH· Reaction Kinetics of Fresh Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) and Dehydrated Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Extracts" Plants 15, no. 1: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010152

APA StyleFiţoiu, M., Pop, A., Vladu, E., Poja, R., Toporîşte, L.-A., Molnar, C. E., Drugă, M., Bujancă, G. S., David, I., Horablaga, A., Hădărugă, N.-G., & Hădărugă, D.-I. (2026). Influence of β-Cyclodextrin on the Overall Antioxidant Activity and DPPH· Reaction Kinetics of Fresh Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) and Dehydrated Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Extracts. Plants, 15(1), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010152