Impact of Bradyrhizobium elkanii and Azospirillum brasilense Co-Inoculation on Nitrogen Metabolism, Nutrient Uptake, and Soil Fertility Indicators in Phaseolus lunatus Genotypes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

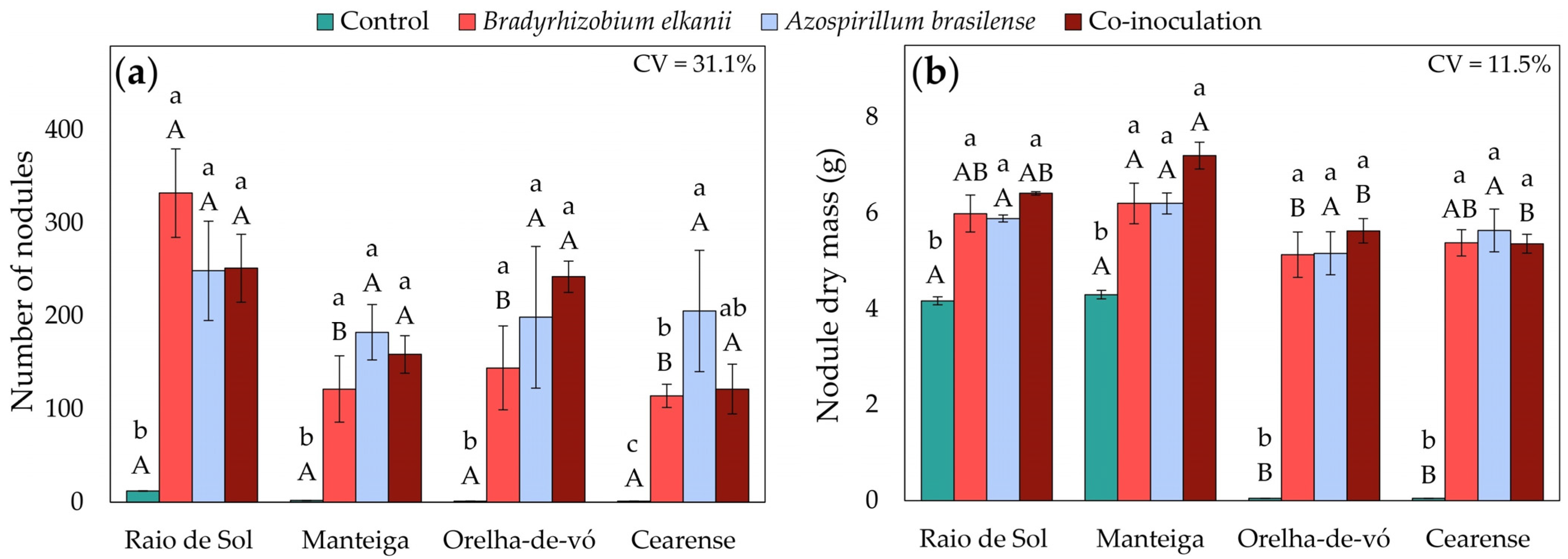

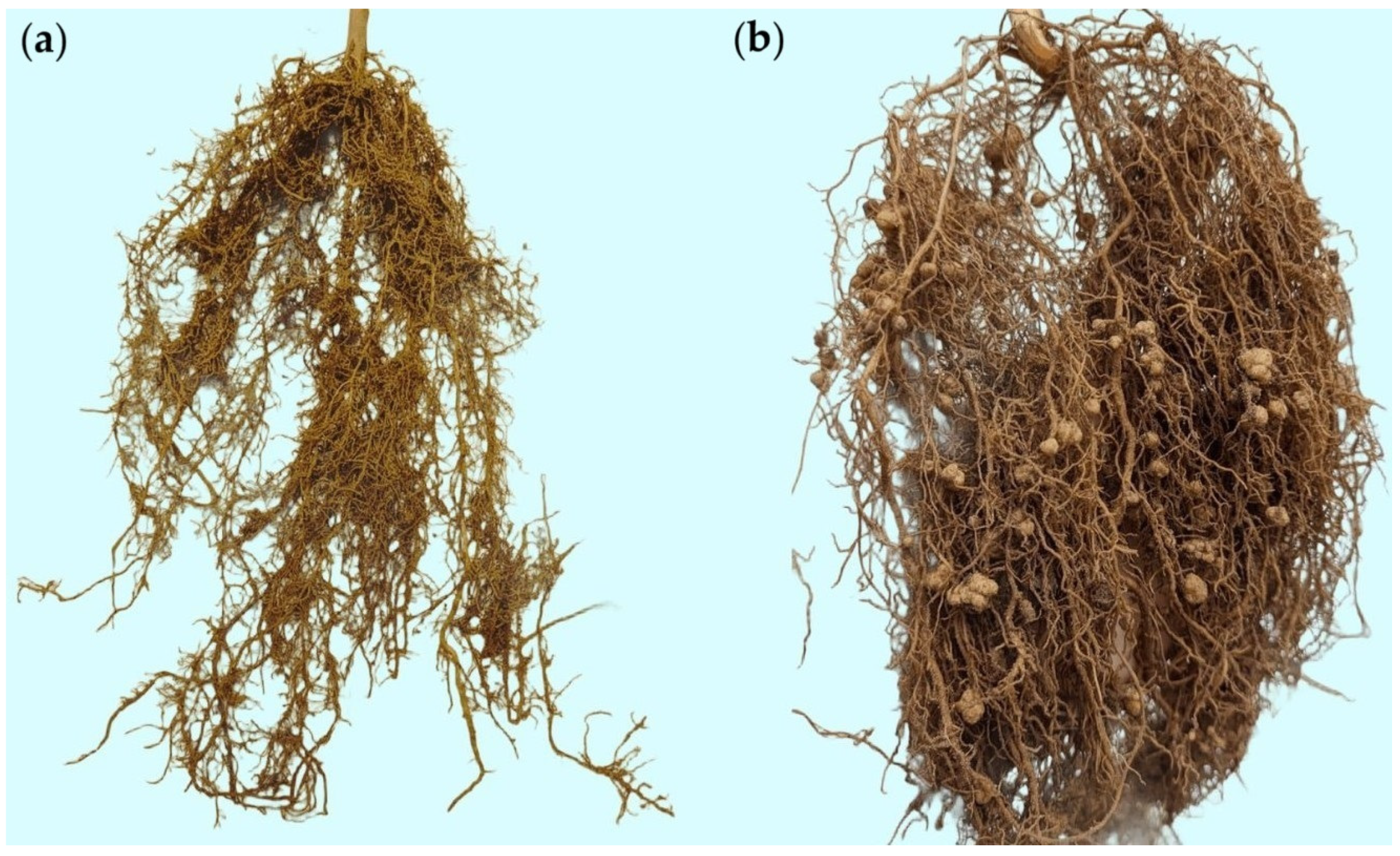

2.1. Root Nodulation

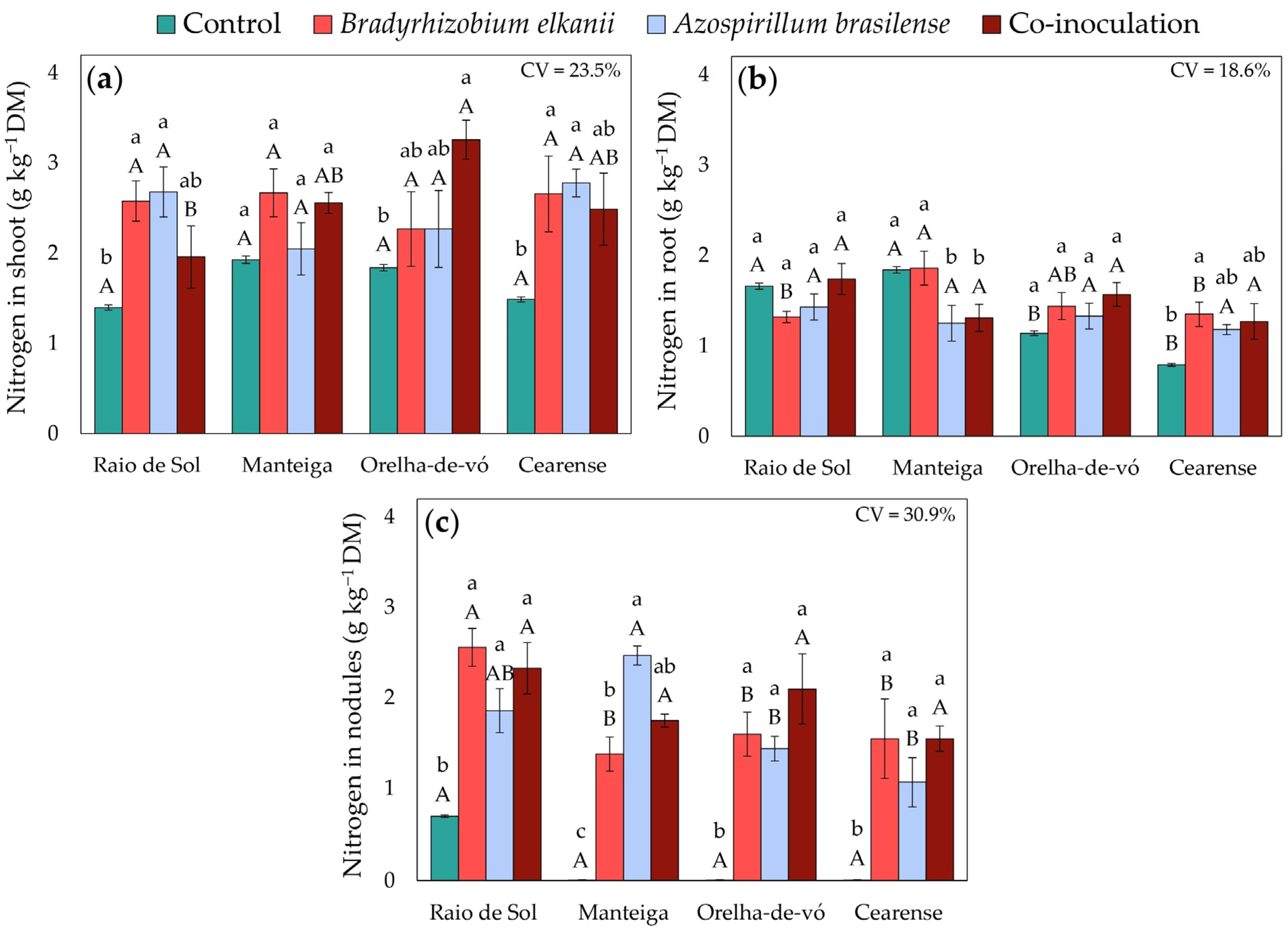

2.2. Nitrogen Accumulation in Different Plant Organs

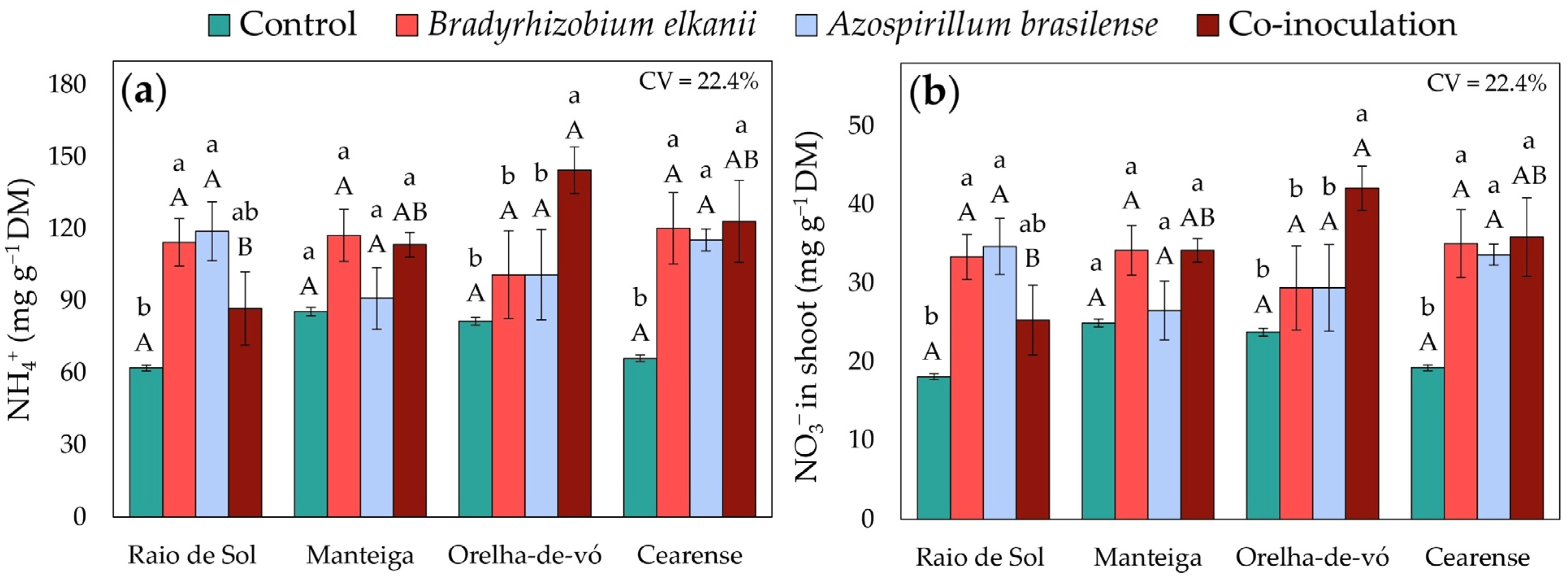

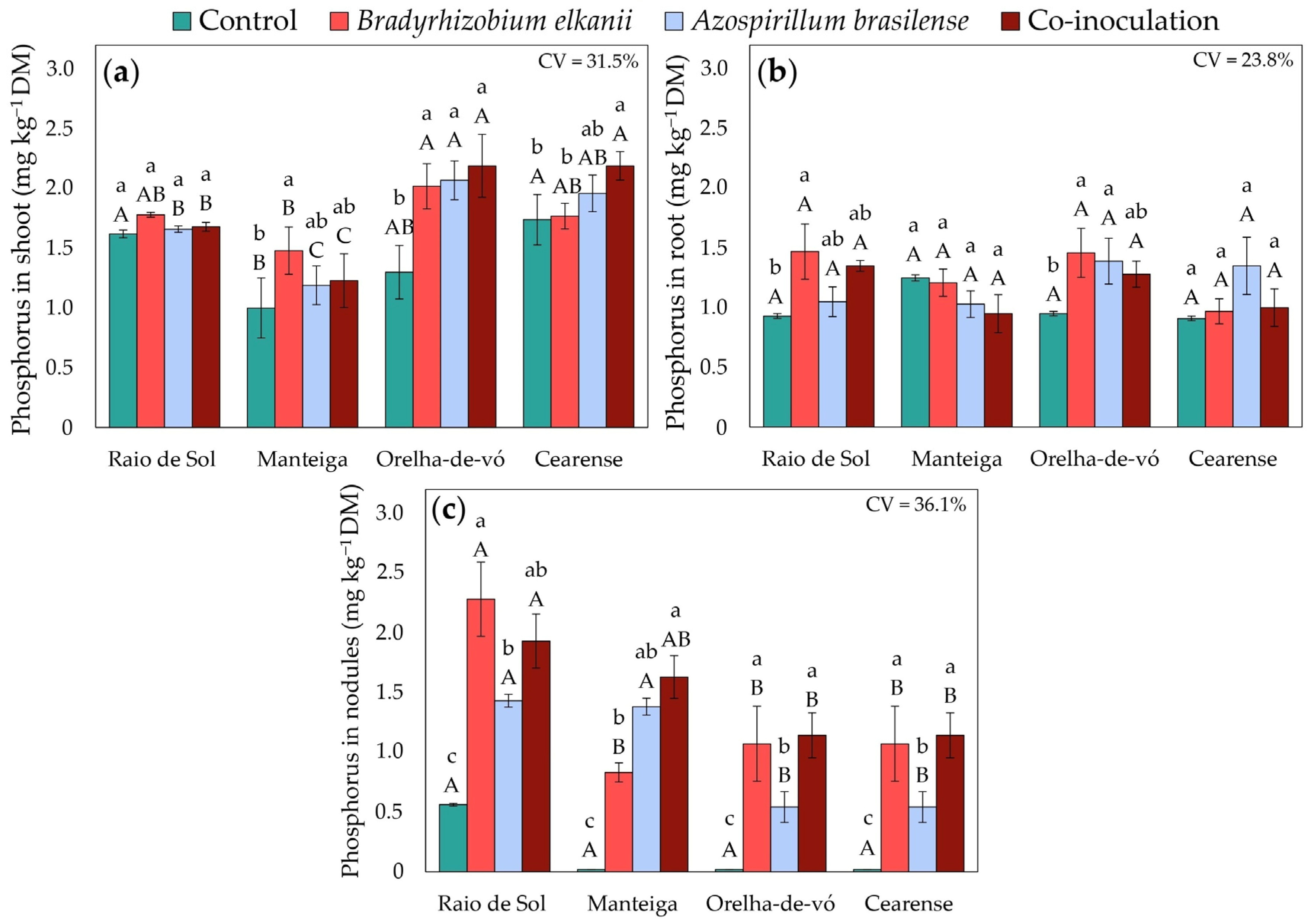

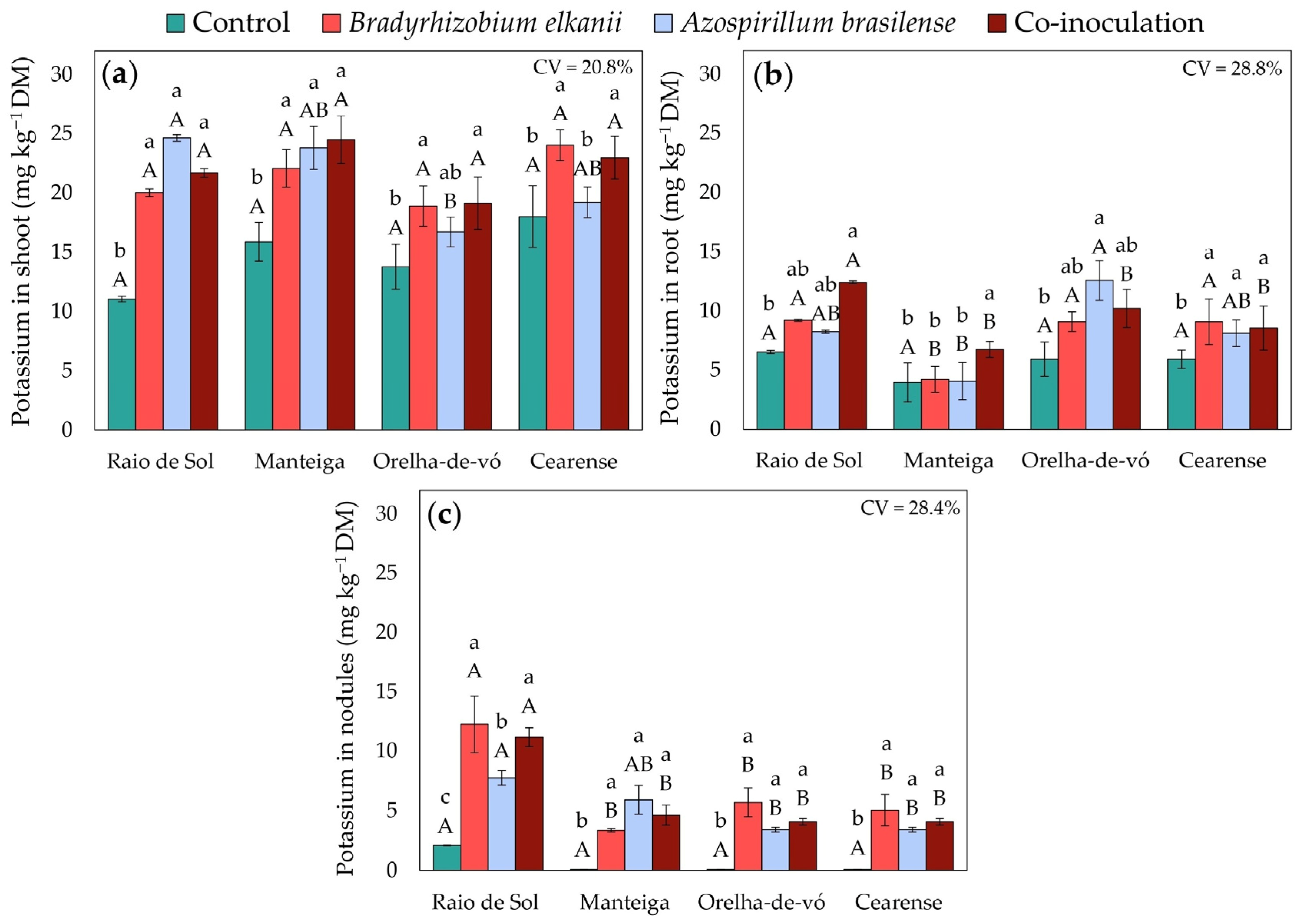

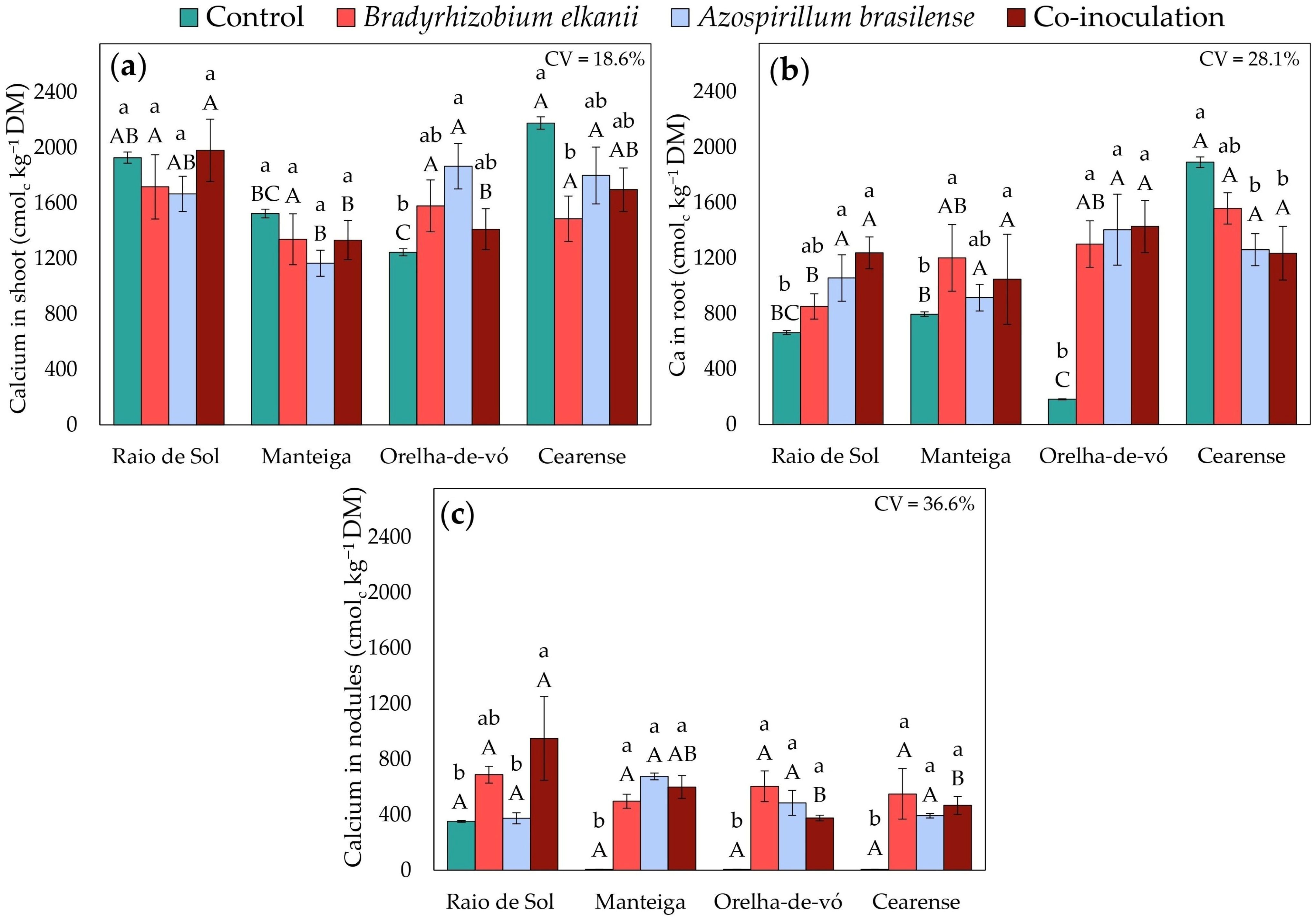

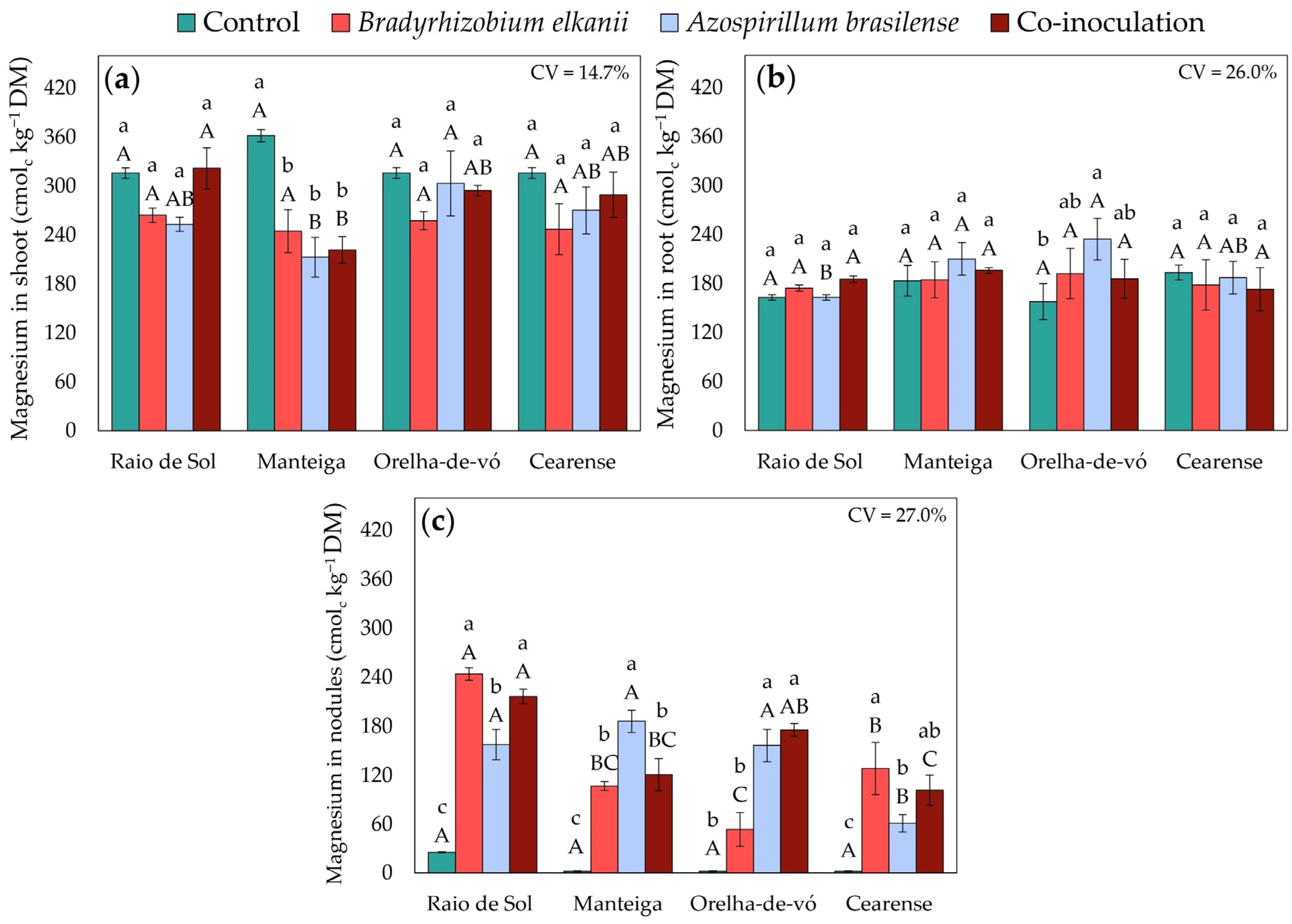

2.3. Nutrient Contents in Different Plant Organs

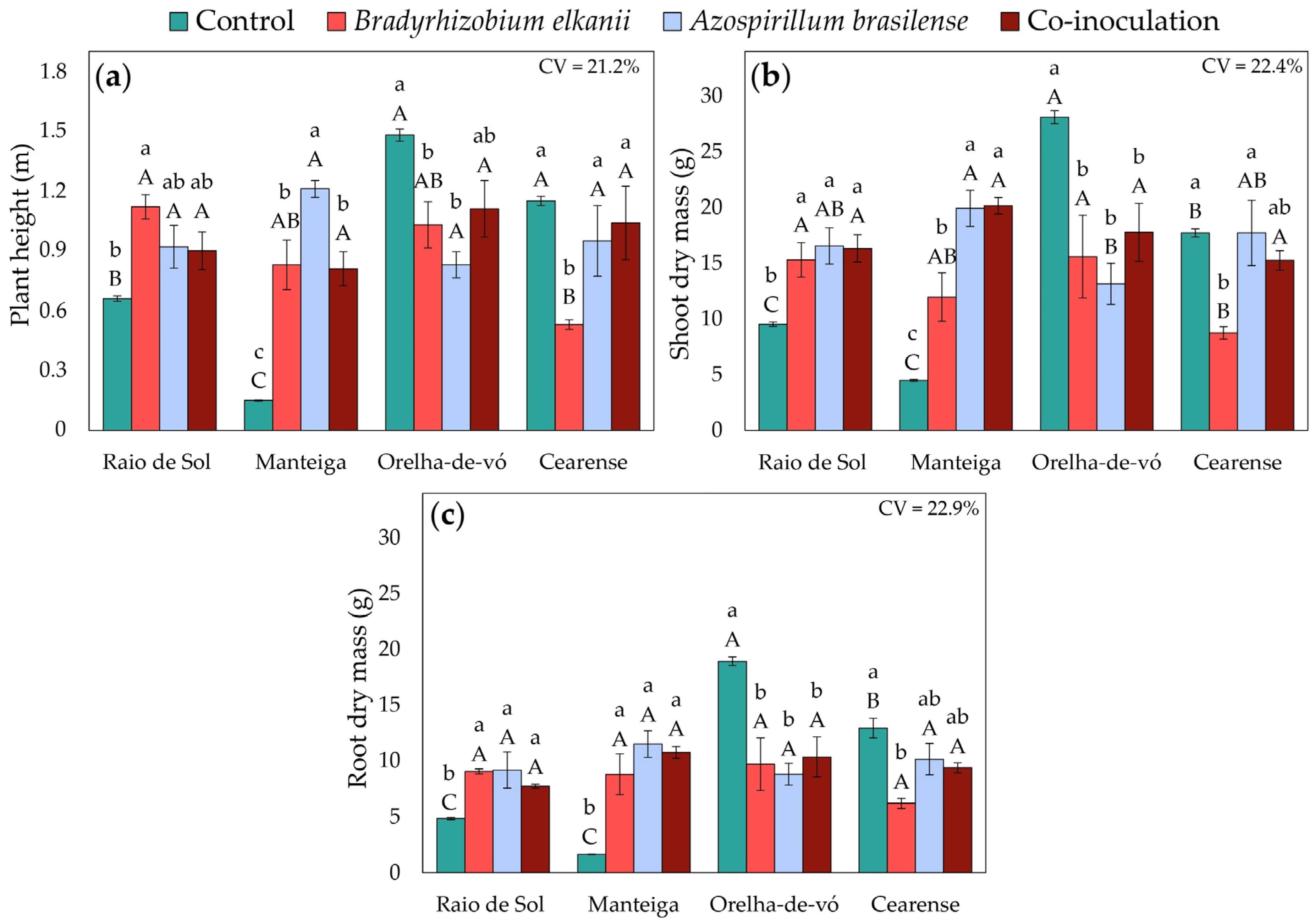

2.4. Plant Growth and Biomass Accumulation

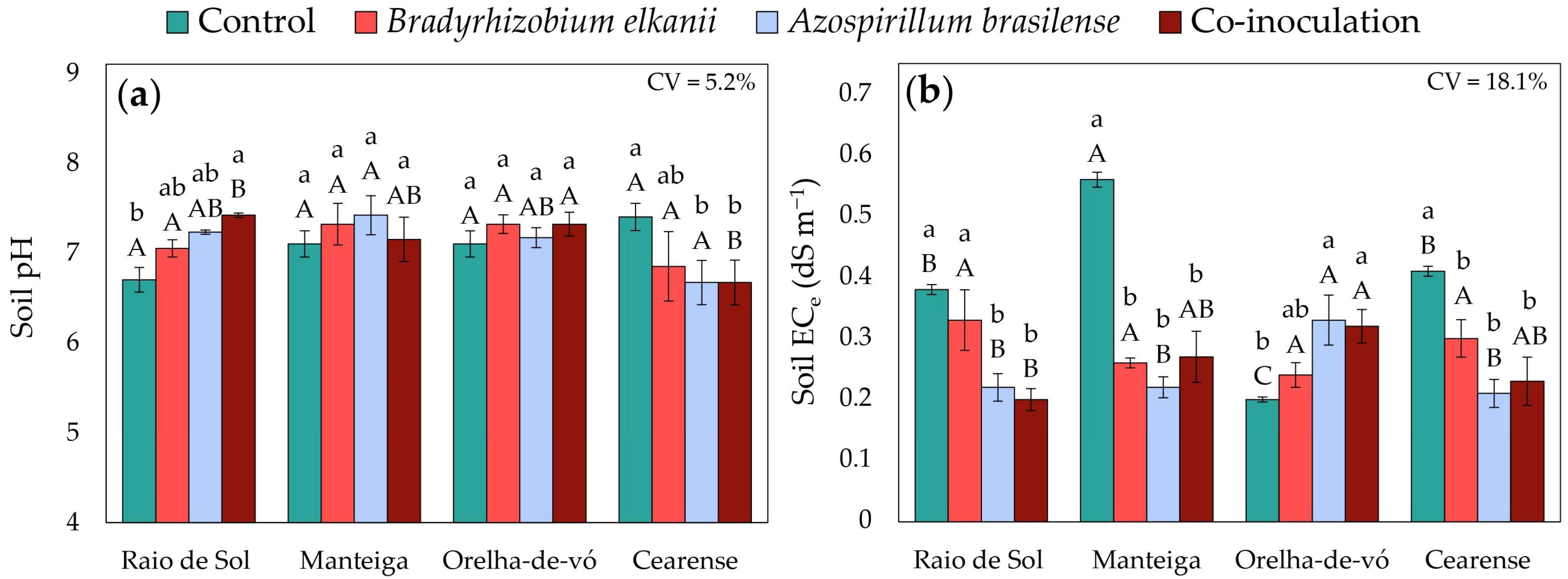

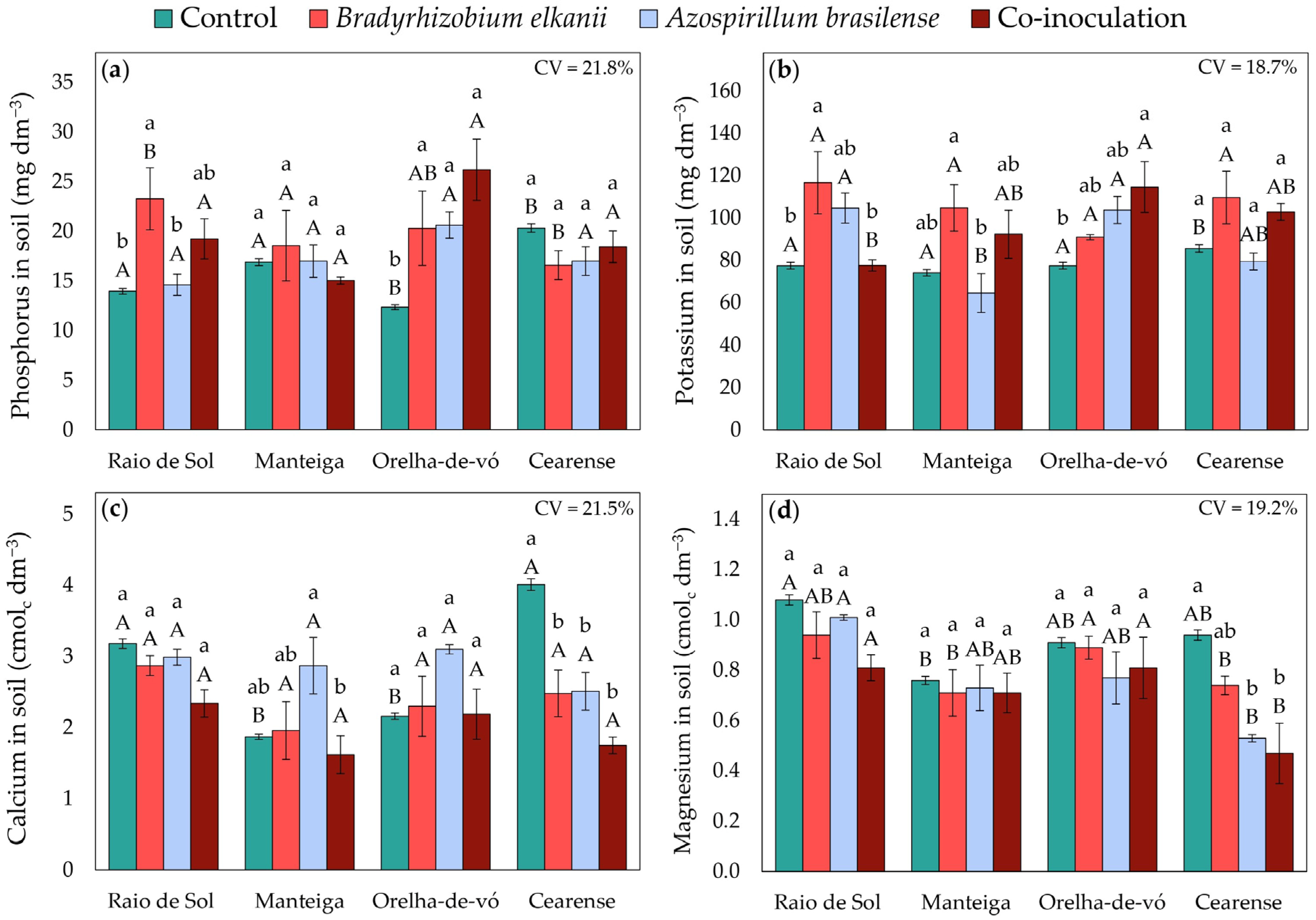

2.5. Soil Fertility Indicators

3. Discussion

3.1. Nodulation and Nitrogen Metabolism

3.2. Plant Nutrition and Growth

3.3. Changes in Soil Fertility Indicators

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Location and Experimental Conditions

4.2. Treatments and Plant Material

4.3. Preparation of Inoculants

4.4. Seed Disinfection, Inoculation, and Sowing

4.5. Experimental Analyses

4.5.1. Root Nodule Formation

4.5.2. Nitrogen Accumulation Analysis

4.5.3. Accumulation of Other Nutrients in Different Plant Organs

4.5.4. Plant Growth and Biomass Analysis

4.5.5. Soil Chemical Properties After Plant Cultivation

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BNF | Biological nitrogen fixation |

| PGPR | Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| DAS | Days after sowing |

| ECe | Electrical conductivity of the soil saturated paste extract |

| ECw | Electrical conductivity of water |

| CEC | Cation exchange capacity |

| UEPB | Paraíba State University |

| YEM | Yeast extract malt |

References

- Semba, R.D.; Ramsing, R.; Rahman, N.; Kraemer, K.; Bloem, M.W. Legumes as a sustainable source of protein in the human diet. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Celebrating the Power of Pulses. FAO News. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/news-archive/detail/the-power-of-pulses (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034. 2025. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/07/oecd-fao-agricultural-outlook-2025-2034_3eb15914/full-report/other-products_8025a1f2.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Yanni, A.E.; Iakovidi, S.; Vasilikopoulou, E.; Karathanos, V.T. Legumes: A vehicle for the transition to sustainability. Nutrients 2024, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunas, B.; Richards, L.; Sergaki, C.; Burgess, J.; Pardal, A.J.; Hussain, R.M.F.; Richmond, B.L.; Baxter, L.; Roy, P.; Pakidi, A.; et al. The nitrogen-fixation efficiency of rhizobians shapes endospheric bacterial communities and the growth of Medicago’s truncated hosts. Microbiome 2023, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jithesh, T.; James, E.K.; Iannetta, P.P.M.; Howard, B.; Dickin, E.; Monaghan, J.M. Recent progress and possible future directions to improve biological nitrogen fixation in the faba (Vicia faba L.). Plant Environ. Interact. 2024, 5, e10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Han, T.; Liu, C.; Sun, P.; Liao, D.; Li, X. Deciphering the effects of genotype and climatic factors on performance, active ingredients and soil properties of the rhizosphere of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, J.A. A review on the potential food application of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.), an underutilized crop. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, S.J.J. Diversidade Geno-Fenotípica de Sementes de Phaseolus lunatus; Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP): São Paulo, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.O.; Araújo, A.S.F.; Gomes, R.L.F.; Lopes, Â.C.A.; Figueiredo, M.V.B. Ontogenia da nodulação em feijão-fava (Phaseolus lunatus L.). Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Agrár. 2009, 4, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, K.R.M. Origin, distribution, taxonomy, botanical description, genetics and cytogenetics, genetic diversity and breeding of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.). Int. J. Recent Adv. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 11, 9956–9972. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, B.B.; Machado, M.J.; Figueira, A. Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Agriculture: Integrating Biotechnology, Microbiology, and Novel Delivery Systems for Sustainable Agriculture. Plants 2025, 14, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcázar-Valle, M.; Lugo-Cervantes, E.; Mojica, L.; Morales-Hernández, N.; Reyes-Ramírez, H.; Enríquez-Vara, J.N.; García-Morales, S. Bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and antinutritional content of legumes: A comparison between four species of Phaseolus. Molecules 2020, 25, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. 2024 Municipal Survey of Agricultural Production. 2025. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/pam/tabelas (accessed on 23 October 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Costa, C.N.; Antunes, J.E.L.; de Almeida Lopes, A.C.; de Freitas, A.D.S.; Araújo, A.S.F. Inoculation of rhizobia increases the yield of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) in soils of the states of Piauí and Ceará, Brazil. Rev. Ceres 2020, 67, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, J.G.C.; Sa, E.L.S.D.; Silva, F.A.D. Efficiency of rhizobia selection in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, using biological nitrogen fixation in Phaseolus lunatus. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 17, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulraheem, M.I.; Moshood, A.Y.; Li, L.; Taiwo, L.B.; Oyedele, A.O.; Ezaka, E.; Chen, H.; Farooque, A.A.; Raghavan, V.; Hu, J. Reactivating the potential of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) to improve soil quality and sustainable stability of soil ecosystems. Agriculture 2024, 14, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.R.; Fernandes Júnior, P.I.; Gomes, D.F.; Rocha, M.M.; Araújo, A.S.F. Current knowledge and future perspectives of the symbiosis of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) and rhizobia. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Agrar. UNCuyo 2019, 51, 280–288. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Neto, V.P.d.; Mendes, J.B.S.; Araújo, A.S.F.; Alcântara Neto, F.; Bonifacio, A.; Rodrigues, A.C. Symbiotic performance, nitrogen flux and growth of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) varieties inoculated with different indigenous rhizobia strains. Symbiosis 2017, 73, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.A.; Zilli, J.E.; Soares, B.L.; Barros, A.L.; Campo, R.J.; Hungary, M. Agroeconomic response of inoculated common bean as affected by nitrogen application throughout the growth cycle. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2022, 43, 2531–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção Neto, W.V.; Medeiros, A.M.; Carvalho, L.C.B.; Ferreira, C.S.; Lopes, A.C.A.; Gomes, R.L.F. Selection of Landraces of Lima Bean for Family Agriculture. Ver. Caatinga 2022, 35, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Junior, F.J.C.; Assunção, M.C.; Silva, T.S. Avanços da Pesquisa e Inovação em Sistemas Agrícolas: Conjunturas da Ciências Agrárias; Editora Científica Digital: São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, M.V.B.; Burity, E.H.A.; Martins, L.M.V.; Stamford, N.P. Eficiência simbiótica de isolados de rizóbio noduladores de feijão-fava (Phaseolus lunatus). Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2011, 35, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Á.L.O.; Setúbal, I.S.; Costa Neto, V.P.d.; Zilli, J.E.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Bonifacio, A. Synergism of Bradyrhizobium and Azospirillum baldaniorum improves growth and symbiotic performance in lima bean under salinity through positive modulations in leaf nitrogen compounds. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 180, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.D.; Souza, A.J.; Nunes, A.L.P.; Rivadavea, W.R.; Zaro, G.C.; Silva, G.J. Expanding agricultural potential through biological nitrogen fixation: Recent advances and diversity of diazotrophic bacteria. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2024, 18, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, Y.; de-Bashan, L.E. How the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum promotes plant growth—A critical assessment. Lawyer Agron. 2010, 108, 77–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassán, F.; Coniglio, A.; López, G.; Molina, R.; Nievas, S.; Carlan, C.L.N.; Donadio, F.; Torres, D.; Rosas, S.; Pedrosa, F.O.; et al. Everything You Need to Know About Azospirillum and Its Impact on Agriculture and Beyond. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, P.; Jin, F.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Shan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Cao, D.; Hao, Q.; et al. Bradyrhizobium elkanii high spectrum efficient and broad Y63-1. Sci. Oilseed Crops 2023, 8, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.P.; Ratu, S.T.N.; Yasuda, M.; Teaumroong, N.; Okazaki, S. Identification of effectors of Bradyrhizobium elkanii USDA61 Type III determining symbiosis with Vigna mungo. Genes 2020, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.B.; Pieri, C.d.; Costa, L.J.S.; Luz, M.N.; Ganga, A.; Capra, G.F.; Passos, J.R.S.; Silva, M.R.; Guerrini, I.A. Inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii reduces nitrogen fertilization requirements for Pseudalbizzia niopoides, a multipurpose neotropical legume tree. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.R.; Chattaraj, S.; Rath, S.; Pattnaik, M.M.; Mitra, D.; Thatoi, H. Revealing the molecular mechanism of Azospirillum in promoting plant growth. Bacteria 2025, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.A.F.; Hungary, M.; Nogueira, M.A. Co-inoculation of Rhizobium tropici and Azospirillum brasilense in common beans grown under two irrigation depths. Rev. Ceres 2016, 63, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, J.; Cerezini, P.; Hungary, M. Co-inoculation of maize with Azospirillum brasilense and Rhizobium tropici as a strategy to mitigate salt stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2017, 45, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hungary, M.; Nogueira, M.A.; Araújo, R.S. Co-inoculation of soybean and common bean with rhizobia and azospirile: Strategies to improve sustainability. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2013, 49, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, É.R.; Marinho, R.C.N.; Silva, J.S.; Teixeira, M.C.C.; Sousa, L.B.; Silva, A.F. Combined inoculation of rhizobia in cowpea development in Cerrado soil. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2017, 48, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, G.C.; Silva, A.S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Moreira, F.M.S. Effects of co-inoculation associated with Bradyrhizobium japonicum with Azospirillum brasilense on soybean yield and growth. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeffa, D.M.; Perini, L.J.; Silva, M.B.; de Sousa, N.V.; Scapim, C.A.; Oliveira, A.L.M.; Amaral Júnior, A.T.D.; Gonçalves, L.S.A. Azospirillum brasilense promotes increases in the growth and nitrogen use efficiency of maize genotypes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pii, Y.; Aldrighetti, A.; Valentinuzzi, F.; Mimmo, T.; Cesco, S. Inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense neutralizes the induction of nitrate uptake in maize plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ali, D.F.I.; Xiong, Y.C.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M.; Hamoud, Y.A.; Ulhassan, Z.; Shagaleh, H.; AbdElgawad, H.; Farooq, M.; et al. Physiological and biochemical responses of soybean plants inoculated with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Bradyrhizobium under drought stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindo, F.S.; Pagliari, P.H.; Silva, E.C.; Fernandes, G.C.; Rodrigues, W.L.; Céu, E.G.O.; Lima, B.H.; Jalal, A.; Muraoka, T.; Buzetti, S.; et al. Co-inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense and Bradyrhizobium sp. improves nitrogen uptake and yield in cowpea grown in the field, without altering the recovery of N fertilizer. Plants 2022, 11, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, P.; Starck, T.; Voisin, A.-S.; Nesme, T. Biological nitrogen fixation of legume crops under organic farming as driven by cropping management: A review. Agric. Syst. 2023, 205, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.F.; Al Achkar, N.; Treccarichi, S.; Malgioglio, G.; Infurna, M.G.; Nigro, S.; Tribulato, A.; Branca, F. Use of bioinoculants affects variation in snap bean yield grown under deficit irrigation. Agriculture 2023, 13, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, C.H.Q.; Cardoso, F.B.; Cândido, A.C.S.; Teodoro, P.E.; Alves, C.Z. Co-inoculation with Bradyrhizobium and Azospirillum increases soybean seed yield and quality. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Suárez, M.; Andersen, S.U.; Poole, P.S.; Sánchez-Cañizares, C. Competition, nodule occupancy, and persistence of inoculant strains: Key factors in the rhizobium–legume symbioses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 19, 690567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastwell, A.H.; Ferguson, B.J. Rhizobia and legume nodulation genes. In Reference Module in Life Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.W.M.; Pérez Marin, A.M.; Leite, J.; Martins, L.M.V.; Ribeiro, P.R.A.; Fernandes Júnior, P.I. Does the Bradyrhizobium pachyrhizi BR 3262 elite strain overcome the native established soil rhizobial population on cowpea nodules occupation? Pesq. Agropecu. Trop. 2024, 54, e79675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xiao, C.; Liu, J.; Ren, G. Nutrient-dependent regulation of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in legumes. Hortic. Res. 2024, 12, uhae321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habinshuti, S.J.; Maseko, S.T.; Dakora, F.D. Inhibition of N2 fixation by N fertilization of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants grown in farmers’ fields in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, measured using natural abundance 15N and tissue ureide analysis. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 692933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Sun, R.; Wang, Z.; Dumack, K.; Xie, X.; Dai, C.; Wang, E.; Zhou, J.; Sun, B.; Peng, X.; et al. The rhizodeposition of legumes promotes nitrogen fixation by the soil microbiota under crop diversification. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, C.B.; Costa Netto, J.R.; Arifuzzaman, M.; Fitschi, F.B. Characterization of genetic diversity and identification of genetic loci associated with carbon allocation in N2-fixing soybean. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, Z.; Sohail, M.N.; Perrine-Walker, F.; Kaiser, B.N. Balancing nitrate acquisition strategies in symbiotic legumes. Planta 2023, 258, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Liu, W.; Nandety, R.S.; Crook, A.; Mysore, K.S.; Pislariu, C.I.; Frugoli, J.; Dickstein, R.; Udvardi, M.K. Celebrating 20 years of genetic discoveries in legume nodulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhu, M.-Y.; Ledermann, R. Division of labor at the nodule: GluTRs from plants feed hemo biosynthesis to symbiosis. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.G.; Chen, Q.S. Molecular mechanisms of nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in Fabaceae. Legume Genom. Genet. 2024, 15, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervent, M.; Lambert, I.; Tauzin, M.; Karouani, A.; Nigg, M.; Jardinaud, M.-F.; Severac, D.; Colella, S.; Martin-Magniette, M.-L.; Lepetit, M. Systemic control of nodule formation by plant nitrogen demand requires mechanisms dependent on and independent of self-regulation. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 7942–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wu, C.; Liu, H.; Lyu, X.; Xiao, F.; Zhao, S.; Ma, C.; Yan, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Systemic regulation of nodule structure and assimilated carbon distribution by nitrate in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1101074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Lu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Fu, M.; Mysore, K.S.; Wen, J.; Gong, J.; Murray, J.D.; et al. The small peptide CEP1 and the NIN-like protein, NLP1, regulate NRT2.1 to mediate root nodule formation through nitrate concentrations. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 776–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuiry, R.; Roy Choudhury, S. Nitrate restricts the expression of non-symbiotic leghemoglobin through inhibition of nodule inception protein in nodules of peanut (Arachis hypogaea). bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancarini, A.; Le Signor, C.; Terrat, S.; Aubert, J.; Salon, C.; Munier-Jolain, N.; Mougel, C. The Medicago truncatula genotype guides the nutritional strategy of the plant and its associated bacterial communities in the rhizosphere. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.; Gerin, F.; Mini, A.; Richard, R.; Le Gouis, J.; Prigent-Combaret, C.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Symbiotic variations among wheat genotypes and loci detection of quantitative traits for molecular interaction with Azospirillum PGPR, auxin producer. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Perez-Limón, S.; Ramírez-Flores, M.R.; Barrales-Gamez, B.; Meraz-Mercado, M.A.; Ziegler, G.; Baxter, I.; Olalde-Portugal, V.; Sawers, R.J.H. Mycorrhizal status and host genotype interact to shape plant nutrition in field-grown maize (Zea mays ssp. Mays). Mycorrhiza 2023, 33, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.I.; Pereira, M.C.; Carvalho, A.M.X.; Buttrós, V.H.; Pasqual, M.; Dória, J. Phosphorus micro-solubris: A key to sustainable agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Cai, B. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: Advances in their physiology, molecular mechanisms, and effects on microbial communities. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, J.; Ying, Y.; Shi, W. The role of phosphate-solubilizing microbial interactions in phosphorus activation and utilization in plant-soil systems: A review. Plants 2024, 13, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Siddique, A.B.; Shabala, S.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, C. Phosphorus plays key roles in regulating plant physiological responses to abiotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, P.M.; Herdean, A.; Adolfsson, L.; Beebo, A.; Nziengui, H.; Irigoyen, S.; Ünnep, R.; Zsiros, O.; Nagy, G.; Garab, G.; et al. The thylakoid transporter Arabidopsis PHT4;1 influences phosphate availability for ATP synthesis and plant growth. Plant J. 2015, 84, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Ye, X.; Song, Y.; Ren, T.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Lu, Z.; Lu, J. Sufficient potassium improves inorganic phosphate-limited photosynthesis in Brassica napus by increasing phosphorus metabolic fractions and Rubisco activity. Plant J. 2023, 113, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, M.; Tang, R.-J.; Tang, Y.; Tian, W.; Hou, C.; Zhao, F.; Lan, W.; Luan, S. Potassium and phosphate transport and homeostasis: Limiting factors for sustainable crop production. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 3091–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Vishwakarma, K.; Hossen, M.S.; Kumar, V.; Shackira, A.M.; Puthur, J.T.; Abdi, G.; Sarraf, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Potassium in plants: Growth regulation, signaling, and tolerance to environmental stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 172, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.A.; Kaniganti, S.; Kumari, P.H.; Reddy, P.S.; Suravajhala, P.; Suprasanna, P.; Kishor, P.B.K. Functional and biotechnological cues of potassium homeostasis for stress tolerance and plant development. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2024, 40, 3527–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Rajput, V.D.; Chauhan, P.K.; Bhojiya, A.A.; Jain, D.; Chaubey, G.; Dwivedi, P.; Sharma, B.; Minkina, T. Root exudates: Mechanistic perception of rhizobacteria that promote plant growth for sustainable crop production. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 916488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Dhital, Y.P.; Zhao, T.; Wang, Z. Isolation and characterization of potassium-solubilizing rhizobacteria (KSR) that promote cotton growth in saline-sodium regions. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, A.; Qamar, Z.U.; Marghoob, M.U.; Imtiaz, M.; Imran, A.; Mubeen, F. Contribution of potassium-solubilizing bacteria in improving potassium assimilation and cytosolic K⁺/Na⁺ ratio in rice (Oryza sativa L.) under saline-sodium conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1196024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, A.G.; Enayatizamir, N.; Masir, M.N. Impact of rhizobacteria promoting plant growth in different forms of potassium in soil under wheat cultivation. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.T.; Qi, W.L.; Nie, M.M.; Xiao, Y.B.; Liao, H.; Chen, Z.C. Magnesium supports nitrogen uptake through the regulation of NRT2.1/2.2 in soybeans. Veg. Soil 2020, 457, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tränkner, M.; Tavakol, E.; Jákli, B. Functioning of potassium and magnesium in photosynthesis, photoprotein translocation and photoprotection. Physiol. Plant 2018. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N.; Zhang, B.; Bozdar, B.; Chachar, S.; Rai, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Hayat, F.; Chachar, Z.; Tu, P. The power of magnesium: Unlocking the potential for increased yield, quality, and stress tolerance of horticultural crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1285512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prell, J.; Poole, P. Metabolic alterations of rhizobia in legume nodules. Microbiol Trends 2006, 14, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, K.; Mousavi, S.A. Efficacy of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 1314–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulieman, S.; Tran, L.S. Phosphorus homeostasis in legume nodules as an adaptive strategy for phosphorus deficiency. Plant Sci. 2015, 239, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zartdinova, R.; Nikitin, A. Calcium in the life cycle of legume root nodules. J. Indian Microbiol. 2023, 63, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, E.H.; Falster, D.S. Quantifying and understanding reproductive allocation schedules in plants. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 5521–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.E.; Ewers, B.E.; Weinig, C. Genotypic variation in biomass allocation in response to field drought has a greater effect on yield than gas exchange or phenology. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Zhao, W.; Xing, M.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, Z.; You, J.; Ni, B.; Ni, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; et al. Resource allocation strategies between vegetative growth, sexual reproduction, asexual reproduction and defense during the growing season of Aconitum kusnezoffii Reichb. Plant J. 2021, 105, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benmrid, B.; Ghoulam, C.; Zeroual, Y.; Kouisni, L.; Bargaz, A. Bioinoculants as a means of increasing crop tolerance to drought and phosphorus deficiency in legume-cereal intercropping systems. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.J.; Mathesius, U. Phytohormone regulation of legume-rhizobia interactions. J. Chem. Ecol. 2014, 40, 770–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepbandit, W.; Athinuwat, D. Rhizosphere microorganisms provide nutrient availability in the soil and induce plant defense. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, C. The role of rhizosphere pH in regulating the rhizosphere priming effect and the implications for soil-derived nitrogen availability to plants. Ann. Bot. 2018, 121, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhade, A.; Wilkinson, E.; Britt, D.W.; Kaundal, A. A review of plant-microorganism interactions in the rhizosphere and the role of root exudates in microbiome engineering. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, S.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Chenari Bouket, A.; Silini, A.; Eshelli, M.; Luptakova, L.; Alenezi, F.N.; Belbahri, L. Improvement of Medicago sativa crop yields by co-inoculation of Sinorhizobium meliloti—Actinobacteria under salt stress. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 1344–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, S.; Daur, I.; Yasir, M.; Waqas, M.; Hirt, H. Synergistic practice of rhizobacteria and silicon improves salt tolerance: Implications of increased oxidative metabolism, nutrient absorption, growth, and grain yield in mung bean. Plants 2022, 11, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Gao, T.; Wang, X.; Chen, R.; Gao, H.; Liu, H. Co-inoculation of Bacillus subtilis and Bradyrhizobium liaoningense increased soybean yield and improved soil bacterial community composition in saline-alkaline coastal lands. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1677763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, N.; Singh, S.; Saxena, G.; Pradhan, N.; Koul, M.; Kharkwal, A.C.; Sayyed, R. A review on transformations of microorganisms and minerals and their impact on plant growth. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1549022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, F.T.; Alori, E.T.; Adekiya, A.O.; Ayorinde, B.B.; Daramola, F.Y.; Osemwegie, O.O.; Babalola, O.O. The use of microbial potassium solubilizers in soil on potassium nutrient availability in soil and its dynamics. Ann. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, M.J.; Gianello, C.; Bissani, C.A.; Bohnem, H.; Volkweiss, S. Analysis of Soil, Plants and Other Materials; Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1995. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.L.; Sheard, R.W.; Moyer, J.R. Comparison of conventional and automated procedures for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium analysis of plant material using a single digestion. Agron. J. 1967, 59, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M.; Keeney, D.R. Determination and analysis of isotopic ratio of different forms of nitrogen in soils: 3. Ammonium, nitrate and nitrite interchangeable by extraction-distillation methods. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1966, 30, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single-solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.C. Manual of Chemical Analysis of Soils, Plants and Fertilizers, 2nd ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2009. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, G.A.; Bastos, J.B.; Lopes, E.C. Methods of Physical, Chemical and Instrumental Analysis of Soils; IPEAN: Belém, Brazil, 1970. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Donagema, G.K.; Campos, D.V.B.; Calderano, S.B.; Teixeira, W.G.; Viana, J.H.M. Manual of Soil Analysis Methods, 2nd ed.; Embrapa: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cruz, G.K.G.d.; Souza, J.A.d.S.d.; de Brito Neto, J.F.; Sousa, C.d.S.; Brito, S.L.; Souza, M.G.M.; Mesquita, E.F.d.; Macedo, R.S.; Cruz, R.L.d.O.; Andrade, V.V.L.d.; et al. Impact of Bradyrhizobium elkanii and Azospirillum brasilense Co-Inoculation on Nitrogen Metabolism, Nutrient Uptake, and Soil Fertility Indicators in Phaseolus lunatus Genotypes. Plants 2026, 15, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010135

Cruz GKGd, Souza JAdSd, de Brito Neto JF, Sousa CdS, Brito SL, Souza MGM, Mesquita EFd, Macedo RS, Cruz RLdO, Andrade VVLd, et al. Impact of Bradyrhizobium elkanii and Azospirillum brasilense Co-Inoculation on Nitrogen Metabolism, Nutrient Uptake, and Soil Fertility Indicators in Phaseolus lunatus Genotypes. Plants. 2026; 15(1):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010135

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruz, Gislayne Kayne Gomes da, José Aliff da Silva de Souza, José Félix de Brito Neto, Cristiano dos Santos Sousa, Samara Lima Brito, Maria Geovana Martins Souza, Evandro Franklin de Mesquita, Rodrigo Santana Macedo, Raíres Liliane de Oliveira Cruz, Vicente Victor Lima de Andrade, and et al. 2026. "Impact of Bradyrhizobium elkanii and Azospirillum brasilense Co-Inoculation on Nitrogen Metabolism, Nutrient Uptake, and Soil Fertility Indicators in Phaseolus lunatus Genotypes" Plants 15, no. 1: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010135

APA StyleCruz, G. K. G. d., Souza, J. A. d. S. d., de Brito Neto, J. F., Sousa, C. d. S., Brito, S. L., Souza, M. G. M., Mesquita, E. F. d., Macedo, R. S., Cruz, R. L. d. O., Andrade, V. V. L. d., Pereira, W. E., & Pereira, R. F. (2026). Impact of Bradyrhizobium elkanii and Azospirillum brasilense Co-Inoculation on Nitrogen Metabolism, Nutrient Uptake, and Soil Fertility Indicators in Phaseolus lunatus Genotypes. Plants, 15(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010135