Dark Septate Endophytic Fungi Improve Dry Matter Production and Fruit Yield in Ever-Bearing Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Under High Temperatures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

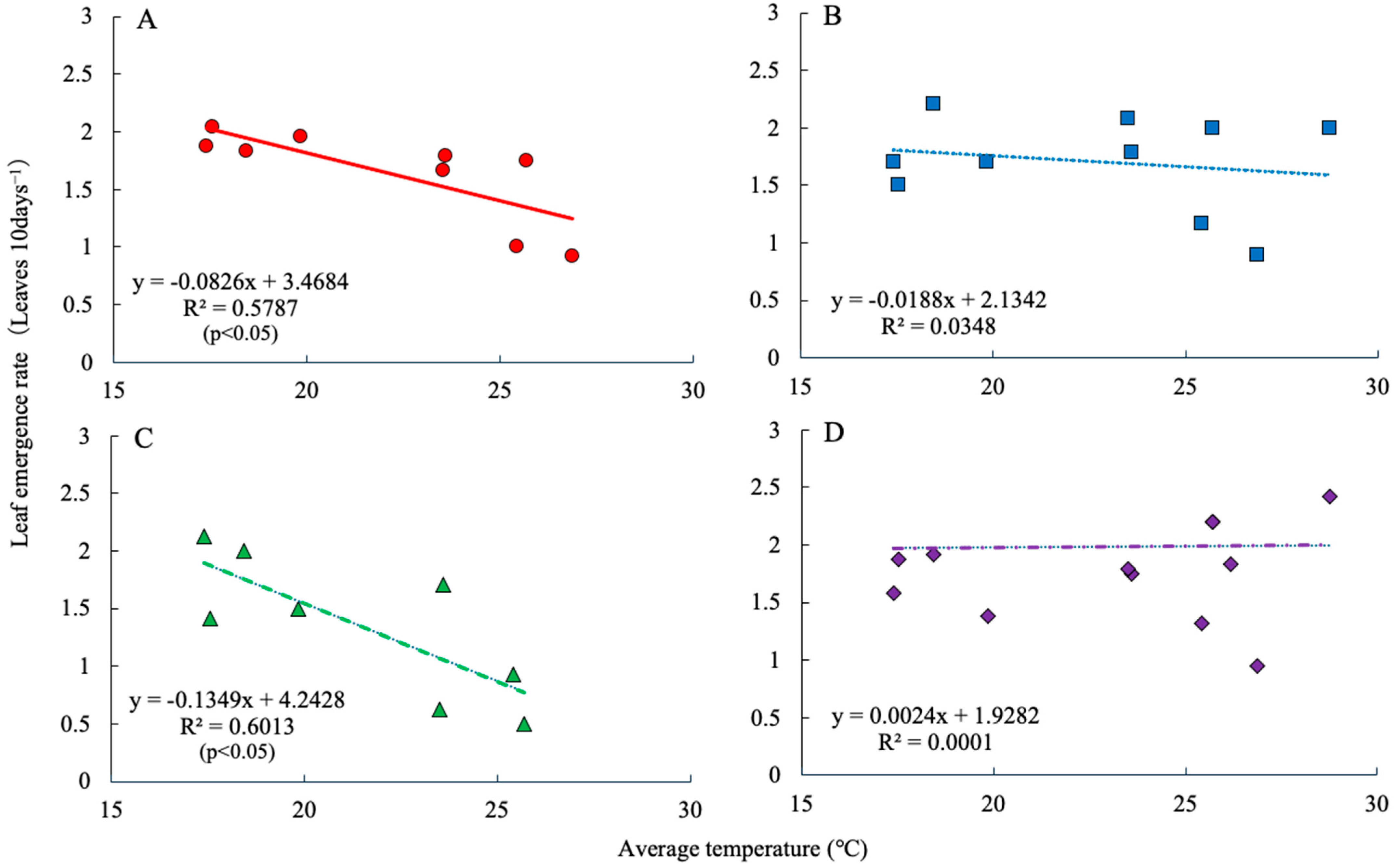

2.1. Dry Matter Production and Leaf Emergence Rate

2.2. Date of Flower Bud Emergence, Flowering, and Fruit Yield

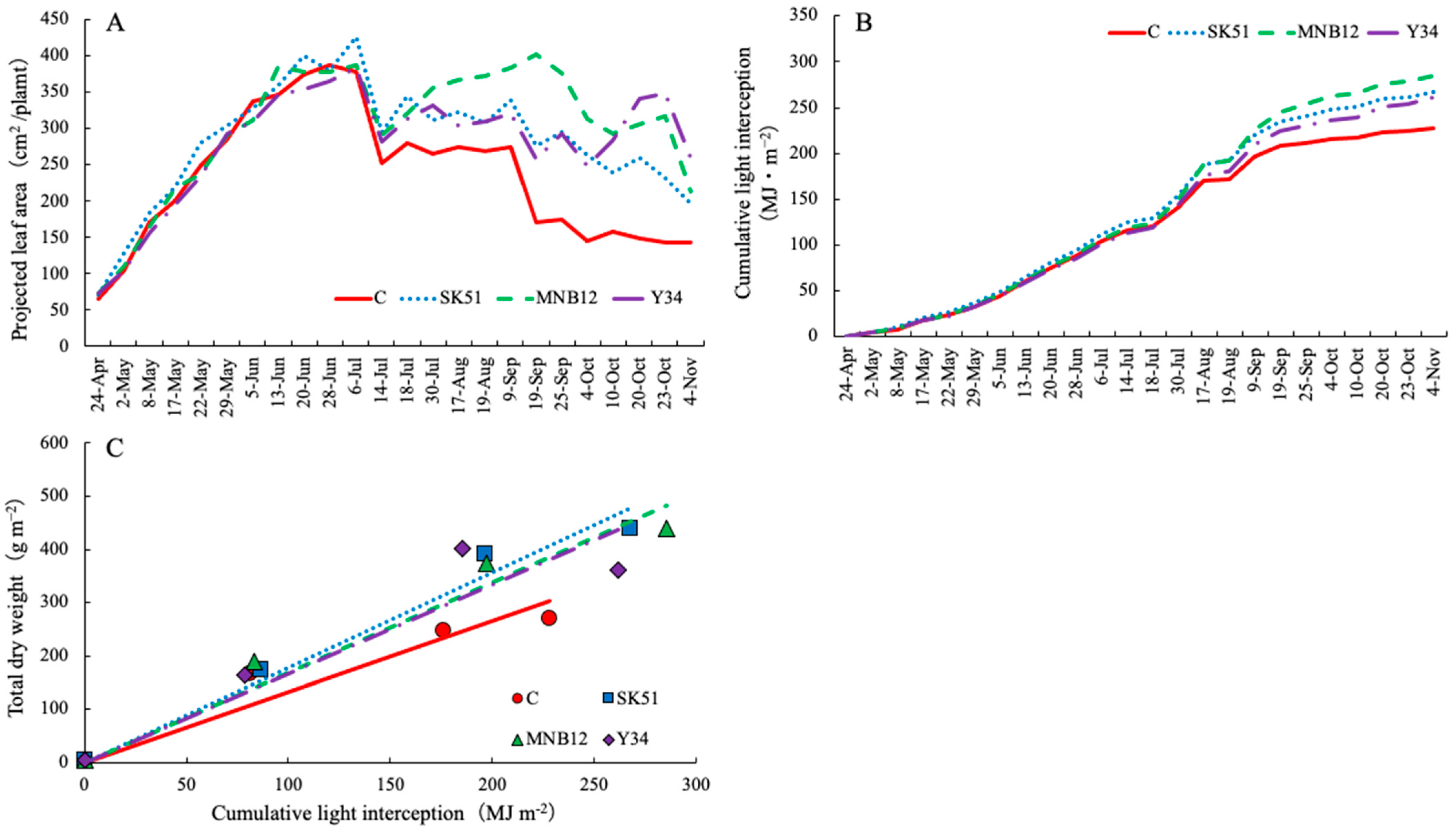

2.3. Projected Leaf Area (PLA), Cumulative Light Interception, and Light Use Efficiency (LUE)

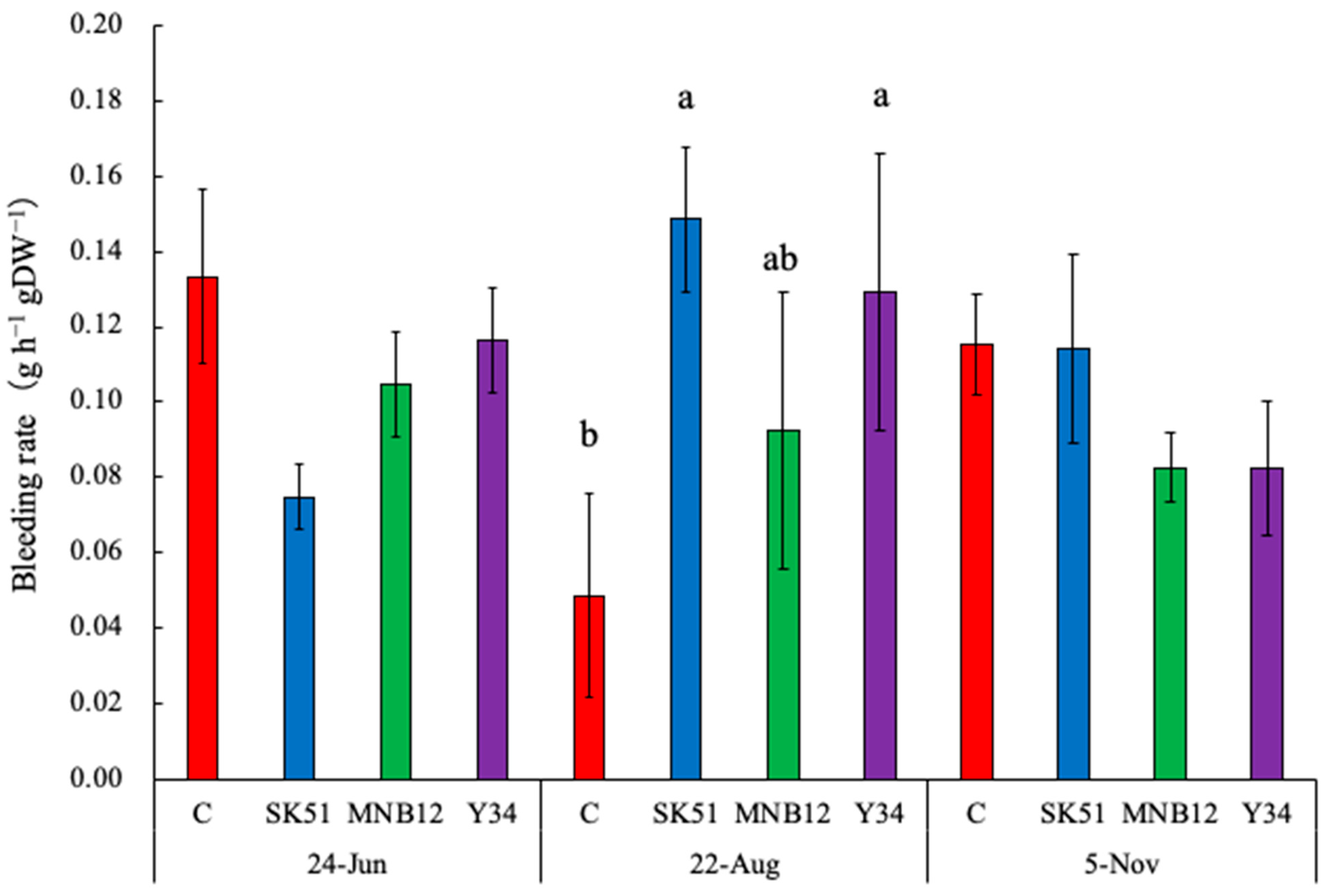

2.4. Root Bleeding Rate and Nitrogen/Carbon Partitioning

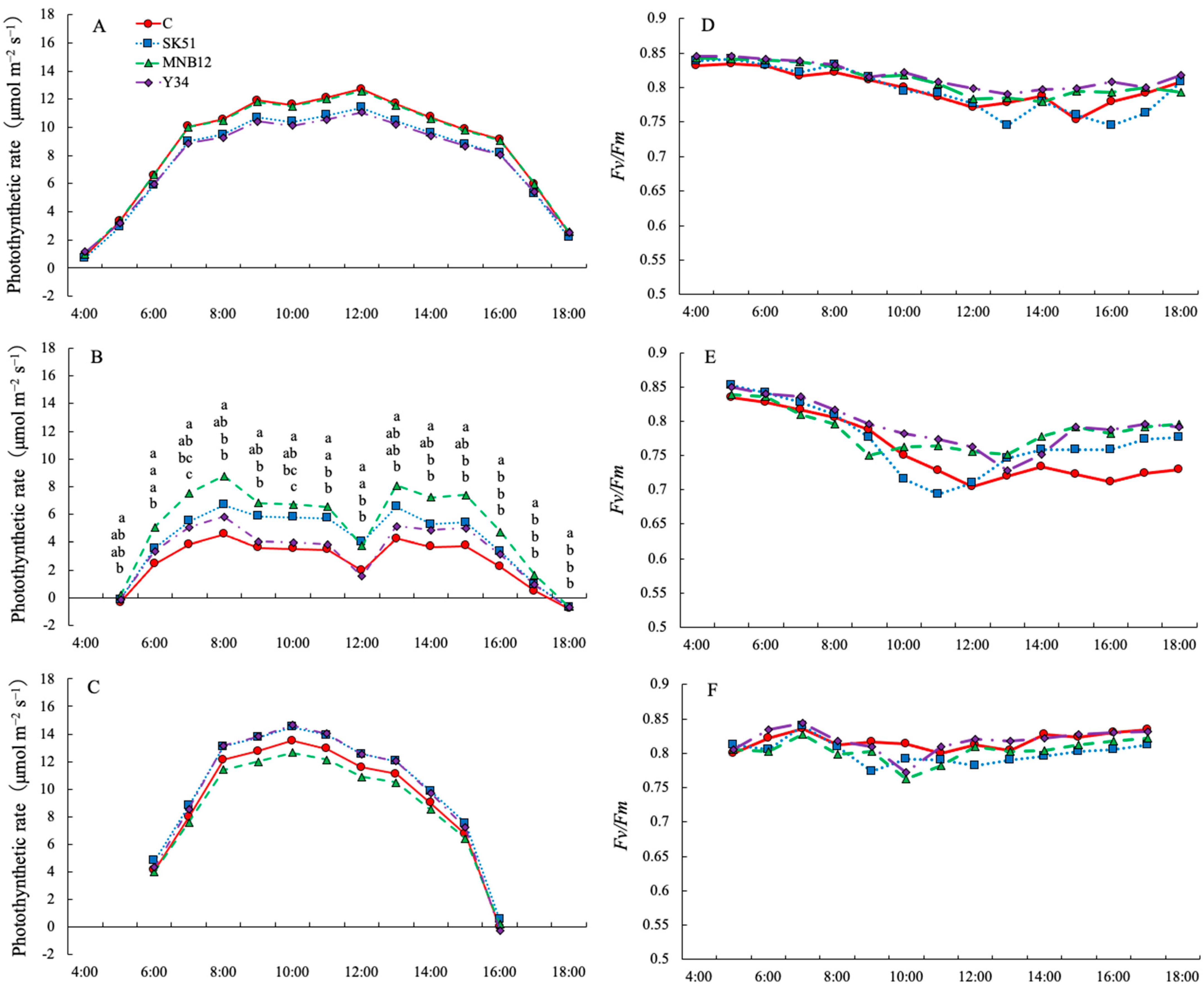

2.5. Diurnal Changes in Photosynthetic Rate and Maximum Quantum Yield of Photosystem II (Fv/Fm)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cultivation and DSE Inoculation

4.2. Dry Matter Production and Leaf Emergence Rate

4.3. Date of Flower Bud Emergence, Flowering, and Fruit Yield

4.4. Projected Leaf Area (PLA), Cumulative Light Interception, and Light Use Efficiency (LUE)

4.5. Root Bleeding Rate and Nitrogen/Carbon Partitioning

4.6. Diurnal Changes in Photosynthetic Rate and Maximum Quantum Yield of Photosystem II (Fv/Fm)

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoshida, Y. Strawberry production in Japan: History and progress in production technology and cultivar development. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2013, 13, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2024. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/shokusan/export/e_info/zisseki.html (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Takano, Y.; Hojo, D.; Sato, K.; Inubushi, N.; Miyashita, C.; Inoue, E.; Mochizuki, Y. Long-term blueberry storage by ozonation or UV irradiation using excimer lamp. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Ishida, S.; Sakaguchi, H.; Inoue, E.; Kawagoe, Y.; Umeda, H. Hyperspectral imaging for estimating substances related to enzymatic browning of strawberry fruits. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food 2025, 18, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumakura, H.; Shishido, Y. Effect of temperature ad photoperiod on flower bud initiation in everbearing type strawberry cultivars. Hort. Res. 1995, 64, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Okimura, M.; Okamoto, K.; Honjo, M.; Yui, S.; Matsunaga, H.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, I.; Fujino, M.; Kataoka, S.; Kawazu, Y. Breeding of new everbearing strawberry cultivar ‘Natsuakari’ and ‘Dekoruju’. Hort. Res. 2011, 10, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T. Effect of temperature during flower bud formation on achene number and fresh weight of strawberries. Hort. Res. 1998, 67, 396–399. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, Y. Abnormal development of flower bud and fruit in strawberry—Factors affecting deformed or malfunctioning floral organs and fruit. Hort. Res. 2024, 23, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, H.; Shishido, Y.; Uchiumi, T.; Kumakura, H. Effects of low light intensity on growth, photosynthesis and distribution of photoassimilates in tomato plants. Environ. Control Biol. 2000, 38, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oowashi, T.; Shibata, M.; Takahashi, N.; Takano, I. Everbearing strawberry production treated with crown cooling during summer to autumn season in the plain of Miyagi prefecture. Bull. Miyagi Prefect. Agric. Horti. Res. Cent. 2014, 82, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, M. Nod factors of root nodule bacteria. JSCRP 1997, 32, 172–185. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S.; Sharma, M.P.; Jajoo, A. Improved photosynthetic efficacy of maize (Zea mays) plants with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) under high temperature stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 180, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jummpponen, A.; Trappe, J.M. Dark septate endophytes: A review of facultative biotrophic root-colonizing fungi. New Phytol. 1998, 140, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuki, F.; Narisawa, K. A mutualistic symbiosis between a dark septate endophytic fungus, Heteroconium chaetospira, and a nonmycorrhizal plant, Chinese cabbage. Mycologia 2007, 99, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Xue, Z. Dark septate endophyte inoculation enhances antioxidant activity in Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus under heat stress. Physiol. Plant 2023, 175, e14054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsonowati, W.; Masrukhin; Narisawa, K. Prospecting the unpredicted potential traits of Cladophialophora chaetospira SK51 to alter photoperiodic flowering in strawberry, a perennial SD plant. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 295, 110835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoletti, F.N.; Tobar, N.E.; Pardo, A.F.D.; Chiocchio, V.M.; Lavado, R.S. Dark septate endophytes present different potential to solubilize calcium, iron and aluminum phosphates. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 111, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likar, M.; Regvar, M. Isolates of dark septate endophytes reduce metal uptake and improve physiology of Salix caprea L. Plant Soil 2013, 370, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khastini, R.O.; Ohta, H.; Narisawa, K. The role of a dark septate endophytic fungus, Veronaeopsis simplex Y34, in fusarium disease suppression in chinese cabbage. J. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsonowati, W.; Marian, M.; Surono; Narisawa, K. The effectiveness of a dark septate endophytic fungus, Cladophialophora chaetospira SK51, to mitigate strawberry fusarium wilt disease and with growth promotion activities. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashide, T.; Heuvelink, E. Physiological and morphological changes over the past 50 years in yield components in tomato. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2009, 134, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Iwasaki, Y.; Funayama, M.; Ninomiya, S.; Fuke, M.; Nwe, Y.Y.; Yamada, M.; Ogiwara, I. Analysis of a high-yielding strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) cultivar ‘Benihoppe’ with focus on dry matter production and leaf photosynthetic rate. J. Jpn. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2013, 82, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Iwasaki, Y.; Fuke, M.; Ogiwara, I. Analysis of a high-yielding strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) cultivar ‘Benihoppe’ with focus on root dry matter and activity. J. Jpn. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2014, 83, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninohei, R.; Yoshino, K.; Noguchi, M.; Sakagami, N.; Narisawa, K.; Mochizuki, Y. Inoculation of dark septate endophyte accelerates flowering and increases yield in strawberry plants. Hort. Res. 2024, 23, 416. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, S.G.D.; Silva, P.R.A.D.; Garcia, A.C.; Zilli, J.E.; Berbara, R.L.L. Dark septate endophyte decreases stress on rice plants. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Eng, X.; Ke, Z. Response of photosynthetic characteristics of Astragalus to high temperature stress and influencing factor analysis under DSE inoculation. Mycosystema 2023, 42, 2294–2308. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, T.; Mochizuki, Y.; Kawasaki, Y.; Ohyama, A.; Higashide, T. Estimation of leaf area and light-use efficiency by non-destructive measurements for growth modeling and recommended leaf area index in greenhouse tomatoes. Hort. J. 2022, 89, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, Y.; Hirano, I.; Sassa, D.; Koshikawa, K. Alleviation of high temperature stress in strawberry plants infected with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Environ. Control Biol. 2004, 42, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Higashide, T.; Yasuba, K.; Ohmori, H.; Nakano, A. Effects of planting stage and density of tomato seedlings on growth and yield component in low-truss cultivation. Hort. Res. 2015, 14, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Umeda, H.; Saito, T.; Higashide, T.; Iwasaki, Y. Effect of low temperature and solar radiation on dry-matter production, fruit yield and emergence of malformed fruit in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.). Acta Hortic. 2018, 1227, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashide, T. Review of dry matter production and growth modelling to improve the yield of greenhouse tomatoes. Hort. J. 2022, 91, 246–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, C. Sensitivity and response of chloroplasts to heat stress in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiba, T.; Morita, S.; Narisawa, K.; Usuki, F. Mechanisms of symbiosis and disease suppression of root endophytic fungus. Nippon Nōgeikagaku Kaishi 2003, 77, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasato, H.; Oowada, T.; Kato, A. Studies on the occurrence of malformed strawberry fruits. 1. The effect of high temperature. Bull. Tochigi Agr. Exp. Stn. 1969, 13, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, L.; Yuli, L.; Chao, H.; Xia, L.; Wanyi, Z.; Xueli, H. Dark septate endophyte enhances Ammopiptanthus mongolicus growth during drought stress through the modulation of leaf morphology and physiology characteristics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120544. [Google Scholar]

- Kanno, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Eguchi, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Higashide, T. Leaf photosynthesis characteristics of seven Japanese strawberry cultivars grown in a greenhouse. Hort. J. 2022, 91, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Sekiguchi, S.; Horiuchi, N.; Aung, T.; Ogiwara, I. Photosynthetic characteristics of individual strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) leaves under short-distance lightning with blue, green and red LED lights. HortScience 2019, 54, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numakura, C.; Noguchi, M.; Asagi, N.; Sakagami, N.; Narisawa, K. Growth of sugar beet e and improvement of heat tolerance by inoculation with symbiotic fungi in Ibaraki Prefectur. Soil Microorg. 2022, 76, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, M. Plant-fungus-bacteria triangular symbiosis as seen through fungal endophytes. Soil Microorg. 2025, 79, 116–138. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, M.; Sakagami, N.; Wibawa, I.; Oikawa, K.; Asagi, N.; Narisawa, K. Effects of inoculation of root endophytes Veronaeopsis simplex and Cladophialophora chaetospira on sugar beet growth and root sugar content. Soil Microorg. 2023, 77, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Murakami, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Worarad, K.; Yonezu, Y.; Umeda, H.; Okayama, T.; Inoue, E. Local CO2 application within strawberry plant canopy increased dry matter production and fruit yield in summer and autumn culture. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2022, 22, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Ninohei, R.; Ohishi, M.; Yonezu, Y.; Okayama, T.; Inoue, E. Effects of air and CO2 application within a strawberry plant canopy on fruit yield and dry matter production during summer and autumn culture. Hort. J. 2024, 93, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsi, M.; Saeki, T. On the factor light in plant communities and its importance for matter production. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Date | DSE | Leaf (gDW m−2) | Crown (gDW m−2) | Root (gDW m−2) | Peduncle (gDW m−2) | Fruit (gDW m−2) | Total (gDW m−2) | Inflorescence (No./Plant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 Apr. | C | 2.28 | 0.12 | 1.01 | ND | ND | 3.41 | ND |

| SK51 | 2.78 | 0.13 | 1.20 | ND | ND | 4.11 | ND | |

| MNB12 | 2.78 | 0.18 | 1.62 | ND | ND | 4.59 | ND | |

| Y34 | 2.97 | 0.14 | 1.41 | ND | ND | 4.52 | ND | |

| 24 Jun. | C | 112.0 | 7.01 | 41.8 | 5.69 | ND | 166.4 | 1.00 |

| SK51 | 115.2 | 6.92 | 47.0 | 4.58 | ND | 173.7 | 1.00 | |

| MNB12 | 128.9 | 8.02 | 47.3 | 4.60 | ND | 188.8 | 0.83 | |

| Y34 | 102.6 | 6.94 | 48.8 | 4.78 | 0.5 | 163.6 | 1.25 | |

| 22 Aug. | C | 141.1 | 9.92 | 30.7 | 17.9 | 48.2 | 247.9 b | 5.00 |

| SK51 | 233.9 | 15.8 | 39.6 | 33.7 | 69.4 | 392.5 ab | 5.00 | |

| MNB12 | 223.6 | 14.6 | 48.9 | 14.9 | 71.5 | 373.6 ab | 4.33 | |

| Y34 | 214.6 | 16.8 | 37.9 | 51.8 | 81.5 | 402.5 a | 7.33 | |

| 5 Nov. | C | 179.2 c | 14.1 b | 18.2 b | 11.8 b | 110.5 b | 333.8 b | 3.30 |

| SK51 | 291.3 a | 26.8 a | 30.5 ab | 24.1 a | 157.0 ab | 529.7 a | 3.80 | |

| MNB12 | 278.7 ab | 26.3 a | 39.0 a | 21.9 ab | 169.3 a | 535.2 a | 4.27 | |

| Y34 | 229.6 abc | 23.2 ab | 29.9 ab | 15.5 ab | 146.5 ab | 444.7 ab | 3.50 |

| DSE | Emergence Date | Flowering Date | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | First | Second | |

| C | 18 Jun. | 6 Jul. | 24 Jun. | 11 Jul. |

| SK51 | 16 Jun. | 8 Jul. | 22 Jun. | 11 Jul. |

| MNB12 | 15 Jun. | 10 Jul. | 21 Jun. | 15 Jul. |

| Y34 | 18 Jun. | 13 Jul. | 24 Jun. | 15 Jul. |

| DSE | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (g m−2) | C | 333.3 | 13.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 346.4 b |

| SK51 | 424.4 | 32.2 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 461.9 a | |

| MNB12 | 434.3 | 23.9 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 459.8 a | |

| Y34 | 403.3 | 34.8 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 441.4 ab | |

| No. fruit (fruit m−2) | C | 67.1 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 73.8 |

| SK51 | 77.0 | 8.8 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 87.9 | |

| MNB12 | 76.9 | 9.7 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 86.9 | |

| Y34 | 66.1 | 14.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 81.5 |

| Leaf | Crown | Root | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | DSE | Nitrogen | Carbon | Nitrogen | Carbon | Nitrogen | Carbon |

| 24 Jun. | C | 1.84 | 46.36 ab | 1.13 | 49.81 | 1.50 ab | 48.39 |

| SK51 | 1.93 | 46.82 ab | 1.11 | 50.80 | 1.36 ab | 47.53 | |

| MNB12 | 1.95 | 45.26 b | 1.45 | 49.22 | 1.80 a | 46.53 | |

| Y34 | 2.07 | 47.96 a | 1.30 | 49.36 | 1.25 b | 46.64 | |

| 22 Aug. | C | 1.61 | 48.33 | 1.75 | 48.57 | 1.34 | 49.25 |

| SK51 | 2.05 | 46.39 | 1.73 | 48.65 | 1.85 | 46.99 | |

| MNB12 | 1.83 | 47.10 | 1.35 | 48.54 | 1.62 | 48.45 | |

| Y34 | 1.93 | 47.05 | 1.60 | 47.91 | 1.53 | 47.84 | |

| 5 Nov. | C | 1.89 | 48.70 | 1.31 | 50.23 | 1.22 | 53.06 |

| SK51 | 2.21 | 50.01 | 1.48 | 50.48 | 1.32 | 53.08 | |

| MNB12 | 2.07 | 49.59 | 1.32 | 49.18 | 1.50 | 51.24 | |

| Y34 | 1.91 | 49.22 | 1.29 | 50.65 | 1.12 | 52.46 | |

| Apr. | May | June | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | 32.5 | 30.1 | 32.2 | 39.0 | 39.5 | 33.9 | 27.6 |

| Min | 14.7 | 15.2 | 18.8 | 24.8 | 27.3 | 23.5 | 15.0 |

| Ave | 21.4 | 21.9 | 24.6 | 30.6 | 32.0 | 27.5 | 20.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aomura, N.; Ninohei, R.; Noguchi, M.; Sakoda, M.; Inoue, E.; Narisawa, K.; Mochizuki, Y. Dark Septate Endophytic Fungi Improve Dry Matter Production and Fruit Yield in Ever-Bearing Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Under High Temperatures. Plants 2026, 15, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010129

Aomura N, Ninohei R, Noguchi M, Sakoda M, Inoue E, Narisawa K, Mochizuki Y. Dark Septate Endophytic Fungi Improve Dry Matter Production and Fruit Yield in Ever-Bearing Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Under High Temperatures. Plants. 2026; 15(1):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010129

Chicago/Turabian StyleAomura, Nanako, Ryuta Ninohei, Mana Noguchi, Midori Sakoda, Eiichi Inoue, Kazuhiko Narisawa, and Yuya Mochizuki. 2026. "Dark Septate Endophytic Fungi Improve Dry Matter Production and Fruit Yield in Ever-Bearing Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Under High Temperatures" Plants 15, no. 1: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010129

APA StyleAomura, N., Ninohei, R., Noguchi, M., Sakoda, M., Inoue, E., Narisawa, K., & Mochizuki, Y. (2026). Dark Septate Endophytic Fungi Improve Dry Matter Production and Fruit Yield in Ever-Bearing Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Under High Temperatures. Plants, 15(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010129