Challenges in Typification Within Taxonomically Complex Groups: The Case of the Linnaean Name Centaurea phrygia (Asteraceae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

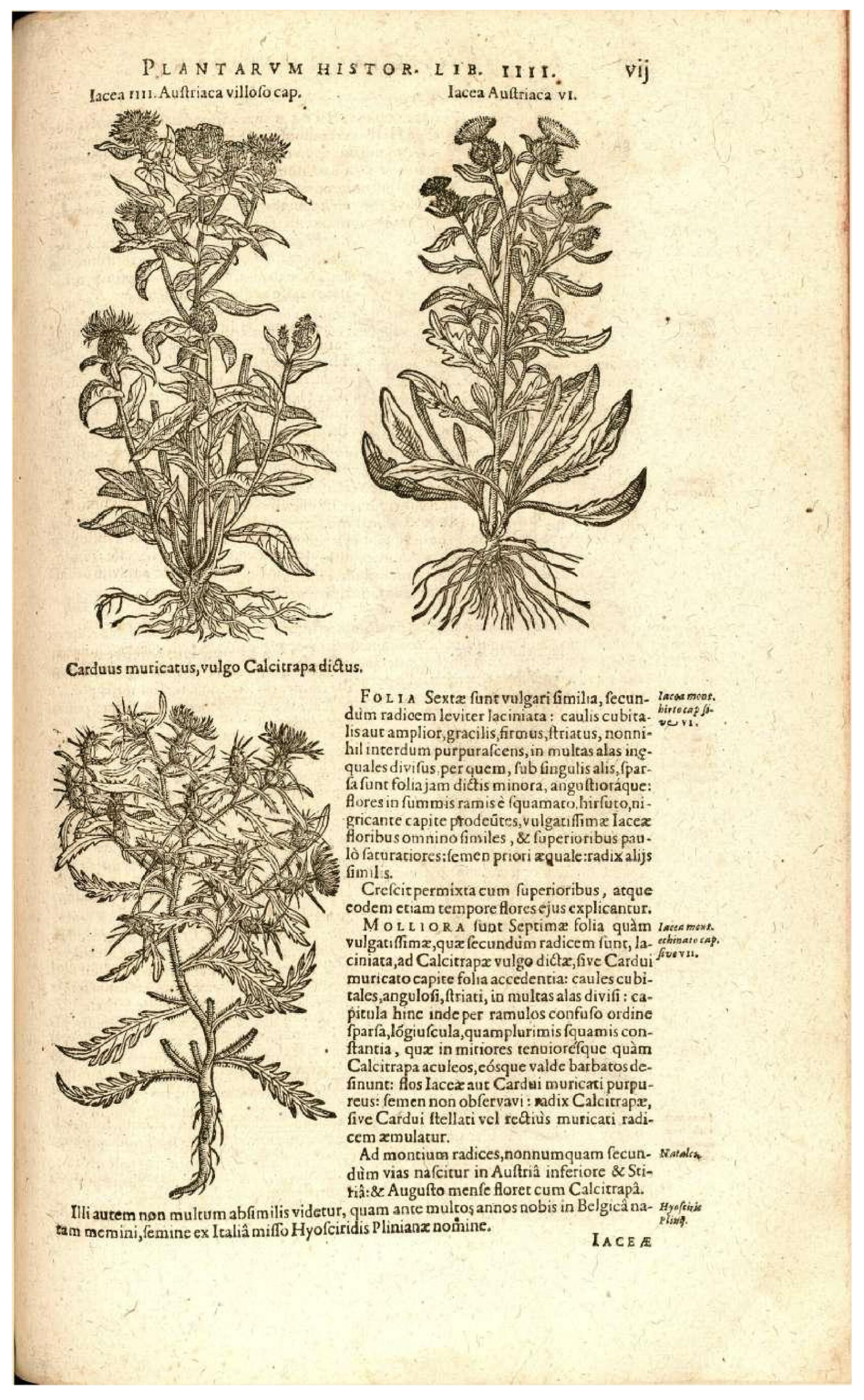

” indicating a perennial plant. Clusius ([38]: 7 vii) provided an illustration that can be considered original material used by Linnaeus to describe C. phrygia (see below).

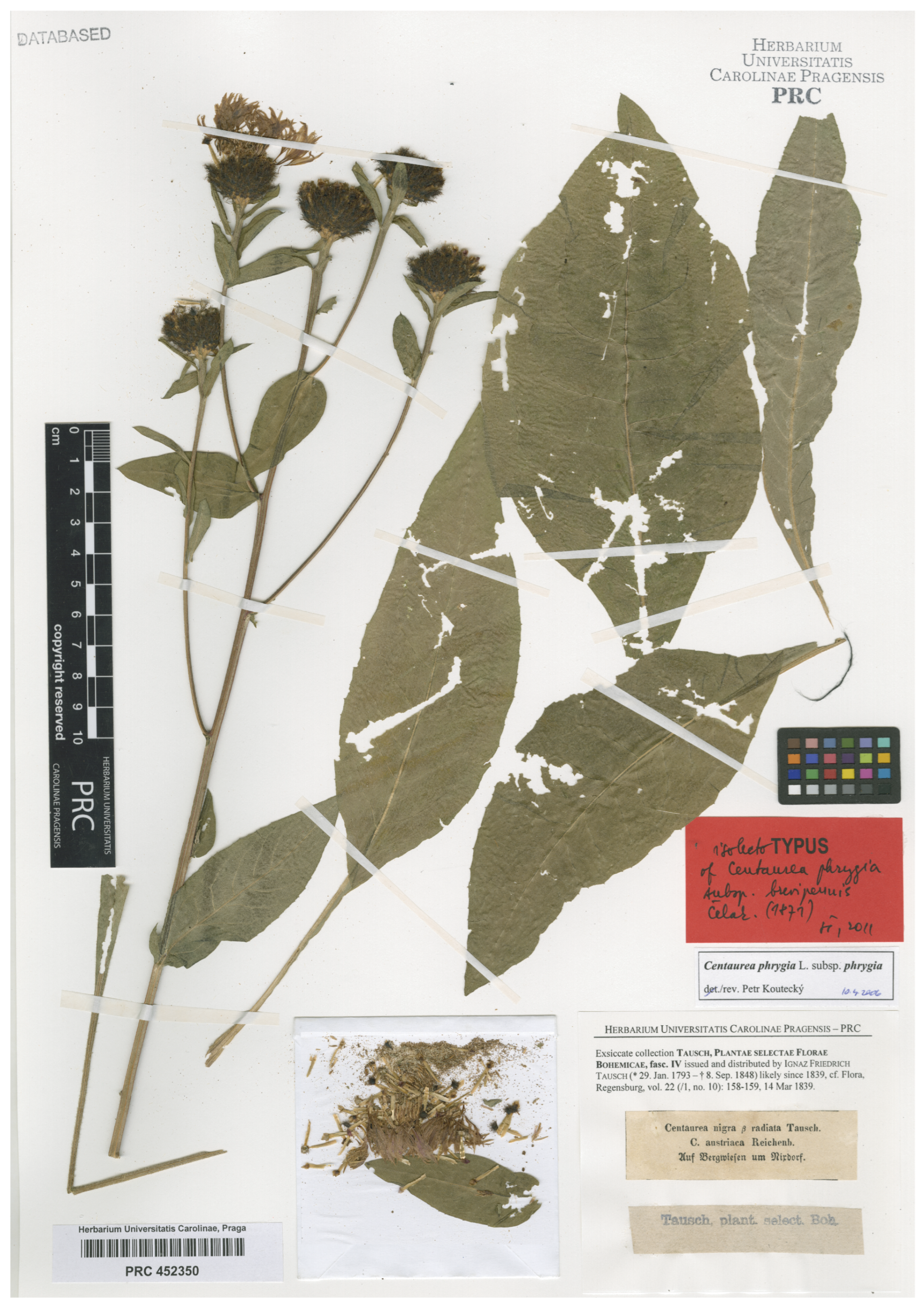

” indicating a perennial plant. Clusius ([38]: 7 vii) provided an illustration that can be considered original material used by Linnaeus to describe C. phrygia (see below). ), and the note “Specimen ex horto Upsal. communicavit Hortulanus Nietzel” [Dietrich Nietzel], indicating that the specimen was provided from the Uppsala garden.

), and the note “Specimen ex horto Upsal. communicavit Hortulanus Nietzel” [Dietrich Nietzel], indicating that the specimen was provided from the Uppsala garden.3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wagenitz, G. Centaurea L. In Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands, vol. 5; Davis, P.H., Ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1975; pp. 465–585. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenitz, G. Centaurea in South-West Asia: Patterns of distribution and diversity. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. 1986, 89B, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostál, J. Centaurea L. In Flora Europaea 4; Tutin, T., Heywood, V., Burges, N., Valentine, D., Walters, S., Webb, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1976; pp. 254–301. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, F. Centaureinae (Asteraceae) in the Mediterranean–history of ecogeographical radiation. Plant Syst. Evol. 2004, 246, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, W. Compositae (Pro Parte Majore). Available online: https://europlusmed.org/cdm_dataportal/taxon/599e0bdb-a2e8-49b9-9907-5398259c4f00 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Susanna, A.; Garcia-Jacas, N. Tribe Cardueae. In The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants, Flowering Plants. Eudicots. Asterales, vol. VIII; Kadereit, J., Jeffrey, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Susanna, A.; Garcia-Jacas, N. Tribe Cardueae. In Systematics, Evolution, and Biogeography of Compositae; Funk, V., Susanna, A., Stuessy, T., Bayer, R., Eds.; IAPT: Vienna, Austria, 2009; pp. 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- POWO. Centaurea L. in Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:330045-2 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Hilpold, A.; Garcia-Jacas, N.; Vilatersana, R.; Susanna, A. Taxonomical and nomenclatural notes on Centaurea: A proposal of classification, a description of new sections and subsections, and a species list of the redefined section Centaurea. Collect. Bot. 2014, 33, e001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutecký, P. Morphological and ploidy level variation of Centaurea phrygia agg. (Asteraceae) in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Ukraine. Folia Geobot. 2007, 42, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonica, G.; Cantor, M. The polymorphism and hybridization of the Centaurea species. Bull. UASVM Hortic. 2011, 68, 444–450. [Google Scholar]

- Vonica, G.; Frink, J.; Cantor, M. Taxonomic revision of some taxa of Jacea-Lepteranthus group (Centaurea genus) based on morphometric analysis. Brukenthal Acta Mus. 2013, 7, 567–584. [Google Scholar]

- Koutecký, P.; Štěpánek, J.; Baďurová, T. Differentiation between diploid and tetraploid Centaurea phrygia: Mating barriers, morphology, and geographic distribution. Preslia 2012, 84, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hultén, E.; Fries, M. Atlas of North European Vascular Plants North of the Tropic of Cancer; Koeltz: Königstein, Germany, 1986; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Meusel, H.; Jäger, E. Arealtypen der süd-mitteleuropäischen Flora. Vgl. Chorologie ZentraleuropäIschen Flora 1992, 3, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, T.; Piirainen, M.; Often, A. Centaurea phrygia subsp. phrygia as a German polemochore in Sør-Varanger, NE Norway, with notes on other taxa of similar origin. Bot. Jahrb. Syst. Pflanzengesch. Pflanzengeogr. 2009, 127, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majovsky, J.; Murin, A. Karyotaxonomicky prehľad Flory Slovenska [Karyotaxonomic Survey of the Flora of Slovakia]; Veda: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dostál, J. Nova Květena Československe Socialisticke Republiky [New Flora of the Czechoslovak Socialistic Republic]; Academia: Prague, Czech Republic, 1989; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Štěpanek, J.; Koutecký, P. Centaurea L. In Květena Česke Republiky [Flora of the Czech Republic]; Slavík, B., Štěpánková, J., Eds.; Academia: Prague, Czech Republic, 2004; Volume 7, pp. 426–449. [Google Scholar]

- Arnelas, I.; Devesa, J. Revisión taxonómica de Centaurea sect. Jacea (Mill.) Pers. (Asteraceae) en la Península Ibérica. Acta Bot. Malacit. 2011, 36, 33–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, C. Order out of Chaos. Linnaean Plant Names and Their Types; The Linnean Society of London with the Natural History Museum: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Klokov, M.; Sosnowsky, D.; Tzvelev, N.; Czerepanov, S. Centaurea; V.L. Komarov Institute, Academy of Sciences of the USSR: Moscow/Leningrad, Russia, 1963; pp. 370–579, [English translation: Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, DC, USA, 2001, pp. 368–577]. [Google Scholar]

- Turland, N.; Wiersema, J.; Barrie, F.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.; Herendeen, P.; Knapp, S.; Kusber, W.H.; Li, D.Z.; Marhold, K.; et al. International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017; Regnum Vegetabile 159; Koeltz Botanical Books: Glashütten, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Gallego, P.; Altınordu, F. Typification of four Linnaean names in Centaurea (Asteraceae). Ann. Bot. Fenn. 2016, 53, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınordu, F. Typification of the Linnaean name Centaurea sibirica (Asteraceae). Phytotaxa 2016, 253, 235–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınordu, F.; Ferrer-Gallego, P. Typifications of Linnaean names in the genus Centaurea and Serratula (Asteraceae). Nord. J. Bot. 2016, 35, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınordu, F.; Ferrer-Gallego, P. Typifications of the Linnaean names Centaurea eriophora and C. orientalis (Asteraceae). Phytotaxa 2016, 277, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınordu, F.; Ferrer-Gallego, P. Typification of the Linnaean name Centaurea crocodylium (Asteraceae). Phytotaxa 2015, 236, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavilla, G.; Lanfranco, S. Neotypification of the name Centaurea crassifolia Bertol. (Asteraceae). Adansonia 2024, 46, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Gallego, P.; Roselló, R.; Laguna, E.; Gómez, J.; Peris, J. Typification of two Linnaean names: Centaurea aspera and Centaurea isnardii (Asteraceae). Phytotaxa 2014, 183, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Gallego, P.; Roselló, R.; Laguna, E.; Guill, A.; Gómez, J.; Peris, J. Typification of the Linnaean name Centaurea seridis (Asteraceae). Phytotaxa 2014, 186, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Gallego, P.; Susanna, A.; Laguna, E.; Guara, M. Lectotypification of Centaurea alpina L. (Compositae) and the identity of Centaurea linaresii Lázaro Ibiza. Taxon 2014, 63, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Hortus Cliffortianus; Salomon Schouten: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1738. [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus, C. Hortus Upsaliensis; Laurentii Salvii: Stockholm, Sweden, 1748. [Google Scholar]

- van Royen, A. Florae Leydensis Prodromus, Exhibens Plantas Quae in Horto acadéMico Lugduno-Batavo Aluntur; Samuel Luchtmans: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalibard, M. Florae Parisiensis Prodromus; Durand et Pissot: Paris, France, 1749. [Google Scholar]

- Bauhin, C. Pinax Theatri Botanici; Sumptibus et typis Ludovici Regis: Basel, Switzerland, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clusius, C. Rariorum Plantarum Historia; Officina Plantiniana: Antverpiae, Belgium, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Species Plantarum; Impensis Laurentii Salvii: Stockholm, Sweden, 1753; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutecký, P. Taxonomic and nomenclatural revision of Centaurea subjacea (Asteraceae-Cardueae) and similar taxa. Phyton Ann. Rei Bot. 2009, 49, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- López-Alvarado, J.; Sáez, L.; Filigheddu, R.; Garcia-Jacas, N.; Susanna, A. The limitations of molecular markers in phylogenetic reconstruction: The case of Centaurea sect. Phrygia (Compositae). Taxon 2014, 63, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, W. Synopsis florae Germanicae et Helveticae, 2nd ed.; Sumptibus Gebhardt et Reisland: Leipzig, Germany, 1844; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C. Ein paar Worte über Centaurea phrygia Linn. Bull. Acad. Imp. Sci. St.-Pétersb. 1848, 6, 132–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sennikov, A.N. The concept of epitypes in theory and practice. Nord. J. Bot. 2022, 2022, e03535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HUH. Botanist Search-HUH-Databases-Harvard University. Available online: https://kiki.huh.harvard.edu/databases/botanist_search.php?mode=details&id=92 (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Thiers, B.M. Index Herbariorum: A Global Directory of Public Herbaria and Associated Staff. Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/ (accessed on 27 March 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tavilla, G.; Crespo, M.B.; Ferrer-Gallego, P.P. Challenges in Typification Within Taxonomically Complex Groups: The Case of the Linnaean Name Centaurea phrygia (Asteraceae). Plants 2025, 14, 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14091336

Tavilla G, Crespo MB, Ferrer-Gallego PP. Challenges in Typification Within Taxonomically Complex Groups: The Case of the Linnaean Name Centaurea phrygia (Asteraceae). Plants. 2025; 14(9):1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14091336

Chicago/Turabian StyleTavilla, Gianmarco, Manuel B. Crespo, and Pedro Pablo Ferrer-Gallego. 2025. "Challenges in Typification Within Taxonomically Complex Groups: The Case of the Linnaean Name Centaurea phrygia (Asteraceae)" Plants 14, no. 9: 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14091336

APA StyleTavilla, G., Crespo, M. B., & Ferrer-Gallego, P. P. (2025). Challenges in Typification Within Taxonomically Complex Groups: The Case of the Linnaean Name Centaurea phrygia (Asteraceae). Plants, 14(9), 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14091336