Physiological Responses of Paulownia fortunei to Leaf Herbivory by Epicauta ruficeps: Nitrogen Assimilation, Porphyrin Metabolism, and ROS-Driven Antioxidant and Phenylpropanoid Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Sample Selection and Collections

2.2. Determination of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

2.3. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigment Content

2.4. Determination of Porphyrin Metabolism Markers

2.5. Determination of Other Physiological and Biochemical Indicators

2.6. Data Analysis and Statistical Figure Plotting

3. Results

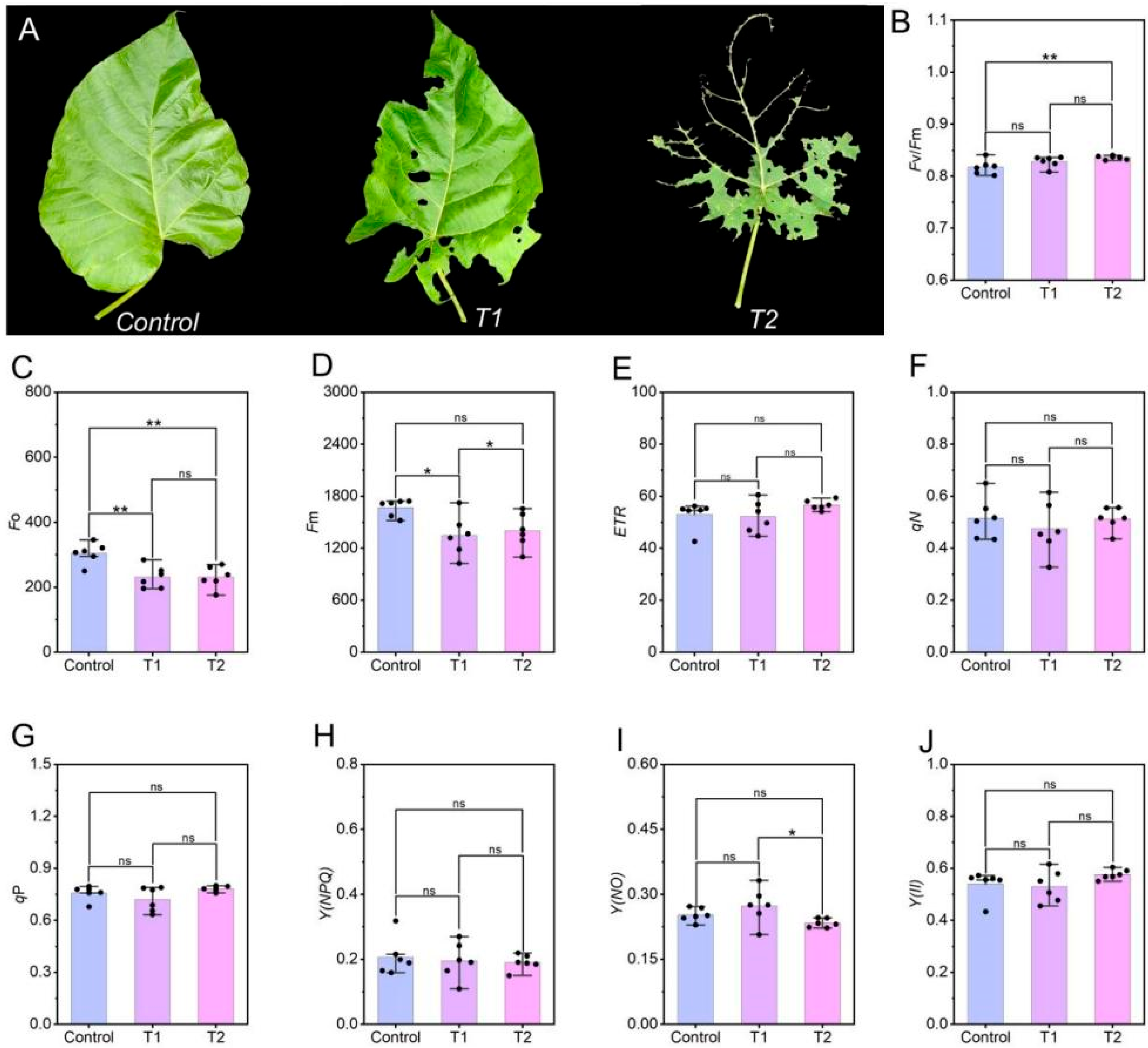

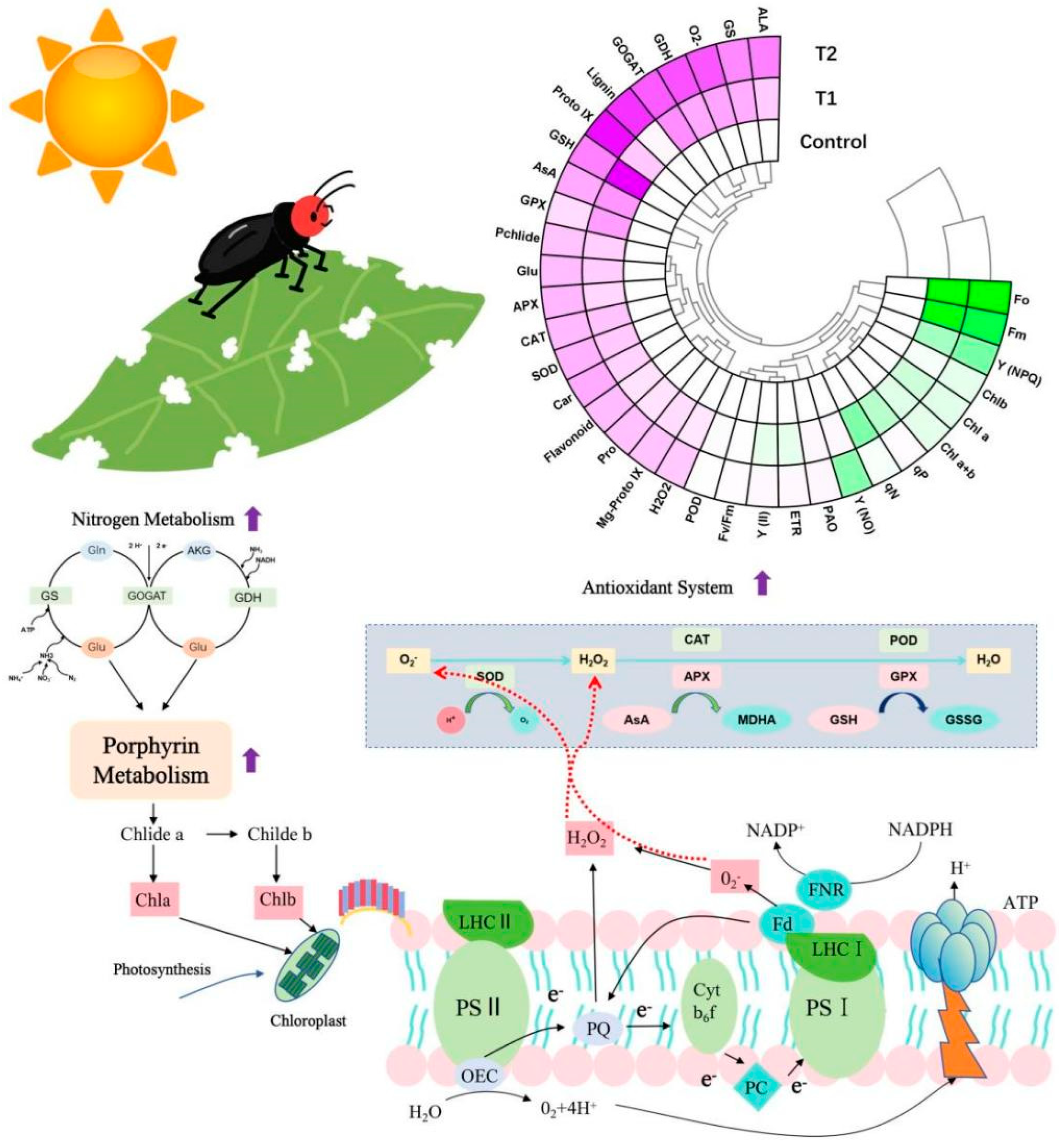

3.1. Effects of E. ruficeps Feeding on P. fortunei Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

3.2. Effects of E. ruficeps Feeding on P. fortunei Nitrogen Metabolism

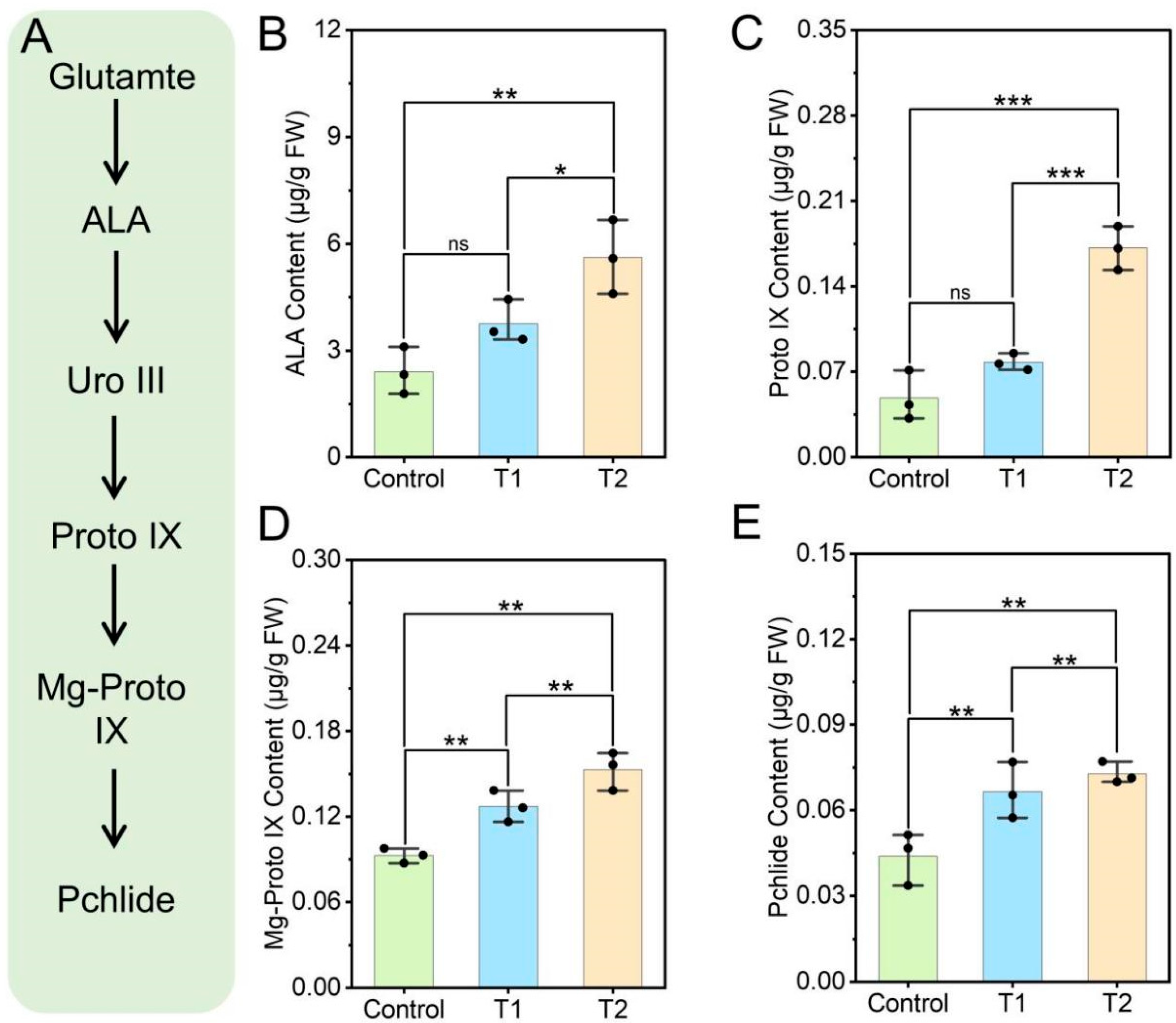

3.3. Effects of E. ruficeps Feeding on P. fortunei Porphyrin Metabolism

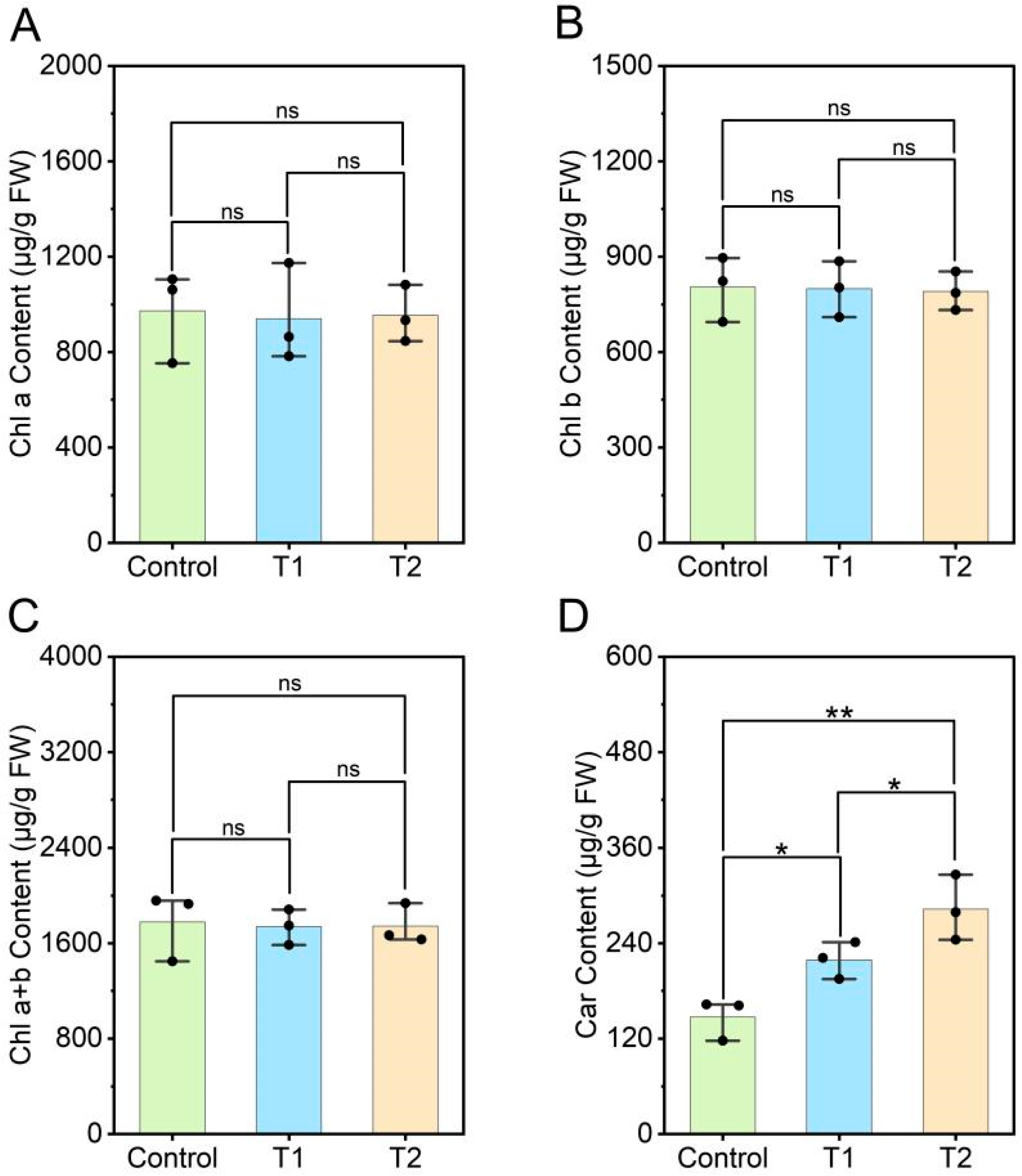

3.4. Effects of E. ruficeps Feeding on the Photosynthetic Pigment Content of P. fortunei

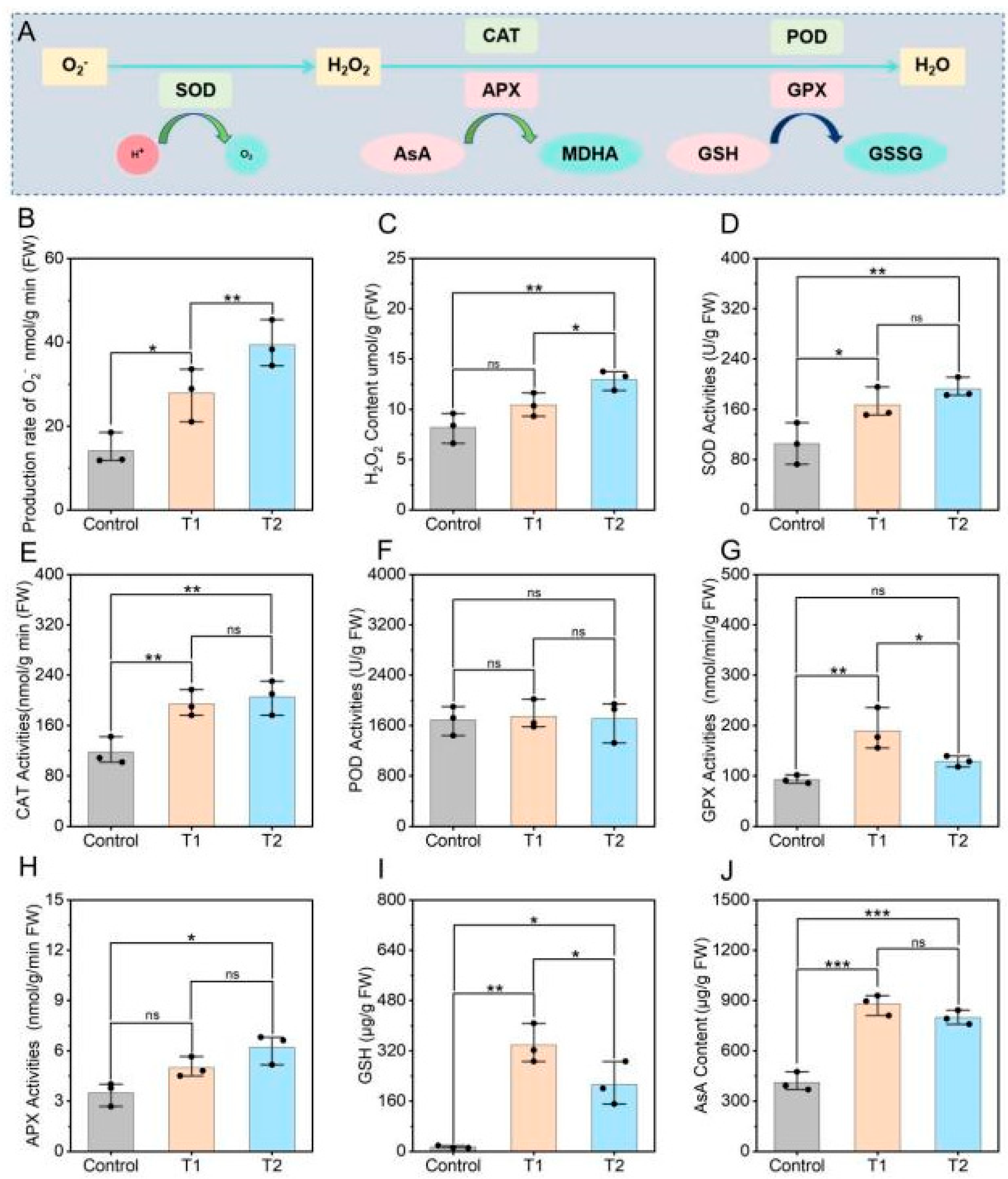

3.5. Effects of E. ruficeps Feeding on the Antioxidant System of P. fortunei

3.6. Effects of E. ruficeps Feeding on Proline Content, Polyamine Oxidase Activity, and Phenylpropanoid Metabolites of P. fortunei

4. Discussion

4.1. The Compensatory Response of P. fortunei to Feeding Pressure from E. ruficeps

4.2. The Defensive Response of P. fortunei to Feeding Pressure from E. ruficeps

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Basu, C.; Joshee, N.; Gezalian, T.; Vaidya, B.N.; Satidkit, A.; Hemmati, H.; Perry, Z.D. Cross-Species PCR and Field Studies on Paulownia Elongata: A Potential Bioenergy Crop. Bioethanol 2016, 2, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Fan, G.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Deng, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W. Proteome Profiling of Paulownia Seedlings Infected with Phytoplasma. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbu, M.C.; Radauer, H.; Petutschnigg, A.; Tudor, E.M.; Kathriner, M. Lightweight Solid Wood Panels Made of Paulownia Plantation Wood. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, B.; Fan, G.; Zhai, X.; Song, W.; Tang, X. A Comprehensive Study on the Bioactive Flavonoids in Paulownia Flowers: Uncovering Metabolic Pathways, Effective Components, and Regulatory Genes for Industrial Applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, M.A.; Turco, F.; Pinto, J.D. The Meloidae (Coleoptera) of Australasia: A Generic Review, Descriptions of New Taxa, and a Challenge to the Current Definition of Subfamilies Posed by Exceptional Variation in Male Genitalia. Invertebr. Syst. 2013, 27, 391–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Lu, C.; Liang, G.; Zhang, F. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Epicauta Ruficeps (Coleoptera: Meloidae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2020, 5, 2049–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blister Beetles (Coleoptera: Meloidae). In Encyclopedia of Entomology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 533–536. ISBN 978-1-4020-6359-6. Available online: https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_384 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- López-Estrada, E.K.; Sanmartín, I.; Uribe, J.E.; Abalde, S.; Jiménez-Ruiz, Y.; García-París, M. Mitogenomics and Hidden-Trait Models Reveal the Role of Phoresy and Host Shifts in the Diversification of Parasitoid Blister Beetles (Coleoptera: Meloidae). Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 2453–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.L.; Selander, R.B. The Biology of Blister Beetles of the Vittata Group of the Genus Epicauta (Coleoptera, Meloidae). In Bulletin of the AMNH; American Museum of Natural History: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume 162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Pan, Z.; Ren, G. Feeding Preference and Mating Behaviors of Epicauta Sibirica(Coleoptera: Meloidae). J. Hebei Univ. 2019, 39, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Baldwin, I.T. New Insights into Plant Responses to the Attack from Insect Herbivores. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2010, 44, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, G.A.; Jander, G. Plant Immunity to Insect Herbivores. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettenhausen, C.; Schuman, M.C.; Wu, J. MAPK Signaling: A Key Element in Plant Defense Response to Insects. Insect Sci. 2015, 22, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fürstenberg-Hägg, J.; Zagrobelny, M.; Bak, S. Plant Defense against Insect Herbivores. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 10242–10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolanchi, P.; Marimuthu, M.; Venkatasamy, B.; Krish, K.K.; Sankarasubramanian, H.; Mannu, J. Phytohormonal Signaling Network and Immune Priming Pertinence in Plants to Defend against Insect Herbivory. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasantha-Srinivasan, P.; Noh, M.Y.; Park, K.B.; Kim, T.Y.; Jung, W.-J.; Senthil-Nathan, S.; Han, Y.S. Plant Immunity to Insect Herbivores: Mechanisms, Interactions, and Innovations for Sustainable Pest Management. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1599450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, A.; Obrępalska-Stęplowska, A. Plant Defense Responses in Monocotyledonous and Dicotyledonous Host Plants during Root-Knot Nematode Infection. Plant Soil 2020, 451, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calf, O.W.; Lortzing, T.; Weinhold, A.; Poeschl, Y.; Peters, J.L.; Huber, H.; Steppuhn, A.; van Dam, N.M. Slug Feeding Triggers Dynamic Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Responses Leading to Induced Resistance in Solanum Dulcamara. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hönig, M.; Roeber, V.M.; Schmülling, T.; Cortleven, A. Chemical Priming of Plant Defense Responses to Pathogen Attacks. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1146577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatehouse, J.A. Plant Resistance towards Insect Herbivores: A Dynamic Interaction. New Phytol. 2002, 156, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G. Plant Compensatory Growth: Its Mechanisms and Implications to Agricultural Sustainability under Global Environmental Changes. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2024, 31, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, P.D.; Bryant, J.P.; Chapin, F.S. Resource Availability and Plant Antiherbivore Defense. Science 1985, 230, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maschinski, J.; Whitham, T.G. The Continuum of Plant Responses to Herbivory: The Influence of Plant Association, Nutrient Availability, and Timing. Am. Nat. 1989, 134, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Yang, G.; Huang, L.-J.; Peng, X.; Cui, C.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Li, N. Integrative Molecular and Physiological Insights into the Phytotoxic Impact of Liquid Crystal Monomer Exposure and the Protective Strategy in Plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, P.; Huzhaotun, H.; Zhongfenge, Z.; Hua, L.S. Effects of Calcium on Physiology and Photosynthesis of Paris Polyphylla Sm. under High Temperature and Strong Light Stress. PAK. J. BOT. 2022, 54, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Jin, X.; Liao, W.; Hu, L.; Dawuda, M.M.; Zhao, X.; Tang, Z.; Gong, T.; Yu, J. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (ALA) Alleviated Salinity Stress in Cucumber Seedlings by Enhancing Chlorophyll Synthesis Pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W. Characterization and Fine Mapping of Thermo-Sensitive Chlorophyll Deficit Mutant1 in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Breed. Sci. 2015, 65, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Jiang, D.; Huang, L.-J.; Cui, C.; Yang, R.; Pi, X.; Peng, X.; Peng, X.; Pi, J.; Li, N. Distinct Toxic Effects, Gene Expression Profiles, and Phytohormone Responses of Polygonatum Cyrtonema Exposed to Two Different Antibiotics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wei, C.; Ma, Q.; Dong, H.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Foyer, C.H.; Yu, J. Ethylene Response Factors 15 and 16 Trigger Jasmonate Biosynthesis in Tomato during Herbivore Resistance. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 1182–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Song, B.; Yu, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bi, R.; Li, X.; Ren, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, D.; et al. Identifying Soybean Pod Borer (Leguminivora glycinivorella) Resistance QTLs and the Mechanism of Induced Defense Using Linkage Mapping and RNA-Seq Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, D.; Cañas, R.A.; Betti, M. Is Plastidic Glutamine Synthetase Essential for C3 Plants? A Tale of Photorespiratory Mutants, Ammonium Tolerance and Conifers. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Martín, M.A.; López-Lozano, A.; Melero-Rubio, Y.; Gómez-Baena, G.; Jiménez-Estrada, J.A.; Kukil, K.; Diez, J.; García-Fernández, J.M. Marine Synechococcus Sp. Strain WH7803 Shows Specific Adaptative Responses to Assimilate Nanomolar Concentrations of Nitrate. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00187-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.-H.; Yu, J.; Go, M.-R.; Kim, H.-J.; Hwang, Y.-G.; Choi, S.-J. Oral Toxicity and Intestinal Transport Mechanism of Colloidal Gold Nanoparticle-Treated Red Ginseng. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Gao, J.; Yi, J.; Zhen, X.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, C.; Zhao, C. An Integrated Analysis of the Rice Transcriptome and Metabolome Reveals Differential Regulation of Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism in Response to Nitrogen Availability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Yuan, Z.; Fu, L.; Zhu, M.; Luo, X.; Xu, W.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, R.; Hu, Z.; Wu, X. Integrative Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis Reveals an Alternative Molecular Network of Glutamine Synthetase 2 Corresponding to Nitrogen Deficiency in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabity, P.D.; Heng-Moss, T.M.; Higley, L.G. Effects of Insect Herbivory on Physiological and Biochemical (Oxidative Enzyme) Responses of the Halophyte Atriplex Subspicata (Chenopodiaceae). Environ. Entomol. 2006, 35, 1677–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhan, M.; Chen, J.; Xu, C. Differential Responses of Leaf Photosynthesis to Insect and Pathogen Outbreaks: A Global Synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 832, 155052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Rascher, U.; Bronstein, J.L.; Davidowitz, G.; Chaszar, B.; Huxman, T.E. Herbivory of Wild Manduca Sexta Causes Fast Down-Regulation of Photosynthetic Efficiency in Datura Wrightii: An Early Signaling Cascade Visualized by Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Photosynth. Res. 2012, 113, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorić, A.S.; Morina, F.; Toševski, I.; Tosti, T.; Jović, J.; Krstić, O.; Veljović-Jovanović, S. Resource Allocation in Response to Herbivory and Gall Formation in Linaria Vulgaris. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperdouli, I.; Andreadis, S.S.; Adamakis, I.-D.S.; Moustaka, J.; Koutsogeorgiou, E.I.; Moustakas, M. Reactive Oxygen Species Initiate Defence Responses of Potato Photosystem II to Sap-Sucking Insect Feeding. Insects 2022, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visakorpi, K.; Gripenberg, S.; Malhi, Y.; Bolas, C.; Oliveras, I.; Harris, N.; Rifai, S.; Riutta, T. Small-Scale Indirect Plant Responses to Insect Herbivory Could Have Major Impacts on Canopy Photosynthesis and Isoprene Emission. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.; Yin, Q.; Zhao, H.; Wang, M.; Sun, X.; Cao, H.; Wang, D.; Li, Q. Disruption of Chlorophyll Metabolism and Photosynthetic Efficiency in Winter Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba) Induced by Apolygus Lucorum Infestation. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1536534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golan, K.; Rubinowska, K.; Kmieć, K.; Kot, I.; Górska-Drabik, E.; Łagowska, B.; Michałek, W. Impact of Scale Insect Infestation on the Content of Photosynthetic Pigments and Chlorophyll Fluorescence in Two Host Plant Species. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2015, 9, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, H. Relationship Between Kilifia Acuminata (Signoret) and Chlorophyll Percentage Loss on Mango Leaves. J. Entomol. 2013, 10, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Y.A.; Ahmed, Q.; Arif, M.A. Does Grape Leafhopper Arbordia Hussaini (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) Effect on Chlorophyll Content of Grape Leaves? IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1060, 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, P.-J.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.-B.; Huang, F.; Li, M.-J. Chlorophyll Content and Chlorophyll Fluorescence in Tomato Leaves Infested with an Invasive Mealybug, Phenacoccus Solenopsis (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). Environ. Entomol. 2013, 42, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, F.U.; Virk, A.L.; Rehmani, M.I.A.; Skalicky, M.; Ata-ul-Karim, S.T.; Ahmad, N.; Soufan, W.; Brestic, M.; Sabagh, A.E.L.; Liqun, C. Integrated Application of Thiourea and Biochar Improves Maize Growth, Antioxidant Activity and Reduces Cadmium Bioavailability in Cadmium-Contaminated Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 809322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Apel, K. 1O2-Mediated and EXECUTER-Dependent Retrograde Plastid-to-Nucleus Signaling in Norflurazon-Treated Seedlings of Arabidopsis Thaliana. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanhui, C.; Tongtong, Y.; Hongrui, W.; Xiaoqian, L.; Zhe, Z.; Zihan, W.; Hongbo, Z.; Ye, Y.; Guoqiang, H.; Guangyu, S.; et al. Abscisic Acid Plays a Key Role in the Mechanism of Photosynthetic and Physiological Response Effect of Tetrabromobisphenol A on Tobacco. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 447, 130792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Cai, M.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Gu, X.; Peng, C. Adaptation of the Invasive Plant (Sphagneticola trilobata L. Pruski) to a High Cadmium Environment by Hybridizing with Native Relatives. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 905577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, B.; Deng, Z.; Li, H. Synergistic Protection of Quercetin and Lycopene against Oxidative Stress via SIRT1-Nox4-ROS Axis in HUVEC Cells. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, R.; Kang, Z.; Gao, K.; Mendgen, K. Mechanisms in Growth-Promoting of Cucumber by the Endophytic Fungus Chaetomium Globosum Strain ND35. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschou, P.N.; Delis, I.D.; Paschalidis, K.A.; Roubelakis-Angelakis, K.A. Transgenic Tobacco Plants Overexpressing Polyamine Oxidase Are Not Able to Cope with Oxidative Burst Generated by Abiotic Factors. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Ma, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, F.; Sang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Ma, L. De Novo Transcriptome Sequencing and Gene Expression Profiling of Magnolia Wufengensis in Response to Cold Stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wan, C. Biological Valorization Strategies for Converting Lignin into Fuels and Chemicals. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Lv, Z.; Xiao, L.; Chen, B.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, G.; Yan, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, G. Physiological Responses of Paulownia fortunei to Leaf Herbivory by Epicauta ruficeps: Nitrogen Assimilation, Porphyrin Metabolism, and ROS-Driven Antioxidant and Phenylpropanoid Responses. Plants 2025, 14, 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233659

Wang F, Lv Z, Xiao L, Chen B, Liu W, Huang J, Liu G, Yan Y, Huang J, Yang G. Physiological Responses of Paulownia fortunei to Leaf Herbivory by Epicauta ruficeps: Nitrogen Assimilation, Porphyrin Metabolism, and ROS-Driven Antioxidant and Phenylpropanoid Responses. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233659

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fan, Zhongke Lv, Lizhi Xiao, Bo Chen, Wenhuan Liu, Jiaqing Huang, Gaoqiang Liu, Yuchen Yan, Jianhua Huang, and Guoqun Yang. 2025. "Physiological Responses of Paulownia fortunei to Leaf Herbivory by Epicauta ruficeps: Nitrogen Assimilation, Porphyrin Metabolism, and ROS-Driven Antioxidant and Phenylpropanoid Responses" Plants 14, no. 23: 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233659

APA StyleWang, F., Lv, Z., Xiao, L., Chen, B., Liu, W., Huang, J., Liu, G., Yan, Y., Huang, J., & Yang, G. (2025). Physiological Responses of Paulownia fortunei to Leaf Herbivory by Epicauta ruficeps: Nitrogen Assimilation, Porphyrin Metabolism, and ROS-Driven Antioxidant and Phenylpropanoid Responses. Plants, 14(23), 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233659