Cloning and Functional Verification of Salt Tolerance Gene HbNHX2 in Hordeum brevisubulatum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of HbNHX Family Members

2.2. Cloning and Characteristics of HbNHX2

2.3. Expression Pattern Analysis of HbNHX2

2.4. Genetic Transformation, Expression, and Phenotypic Analysis of Transgenic Tobacco

2.5. Physiological Response of Transgenic Tobacco Under Salt Stress

2.6. Expression of Stress-Responsive Genes in Transgenic Tobacco

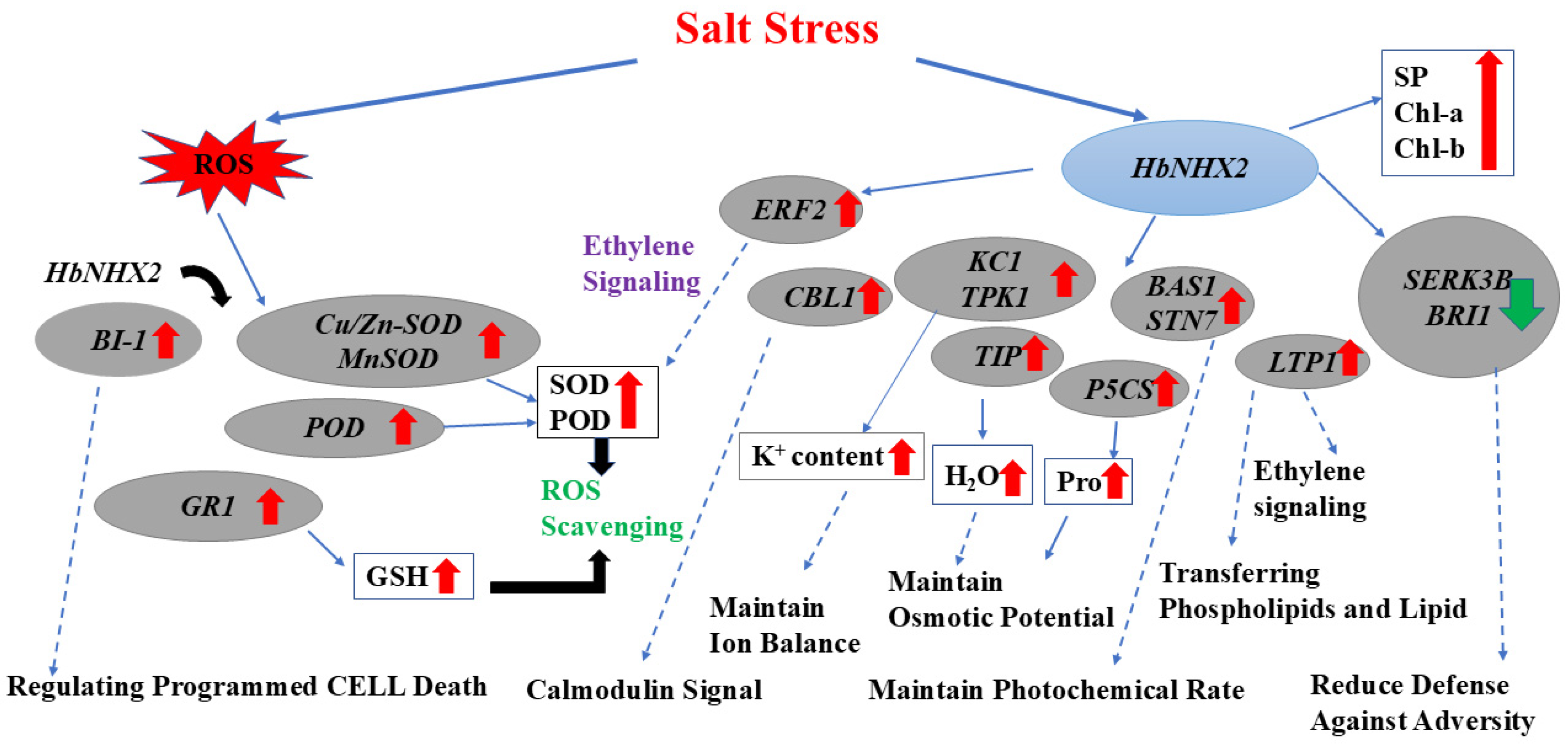

3. Discussion

3.1. HbNHX2 and the NHX Gene Family in Plant Salt Tolerance

3.2. Functional and Physiological Characterization of HbNHX2 Was Studied Using Genetic Transformation

3.3. Transcriptional Regulation of Stress-Responsive Genes in HbNHX2-Overexpressing Plants

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Growth and Treatment

4.2. Identification of HbNHX Gene Family Members

4.3. Isolation and Cloning of HbNHX2

4.4. Expression Pattern Analysis of Tissue Specificity and Stress Response of HbNHX2 Gene

4.5. Plant Transformation and Generation of Transgenic Tobacco

4.6. Subcellular Localization of HbNHX2 Protein

4.7. Physiological Index of Homozygous Lines Subjected to Salt Stress

4.8. Expression Analysis of Stress-Responsive Gene Subjected to Salt Stress

4.9. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| O2− | Superoxide anion |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| K326 | Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. K326 |

| CBL1 | Calcineurin B-like 1 |

| ERF2 | Ethylene-Responsive Factor |

| BI-1 | Bax inhibitor-1 |

| MnSOD | Superoxide dismutase [Mn] |

| Cu/Zn-SOD | Superoxide dismutase [41Cu-Zn] |

| POD | Nicotiana tabacum Peroxidase |

| GR1 | Protein gamma response 1. |

| KC1 | Potassium channel KAT3-like 1. |

| TPK1: | Two-pore potassium channel 1-like 1 |

| TIP | Aquaporin TIP-type |

| P5CS | Delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase |

| BAS1 | 2-Cys peroxiredoxin |

| STN7 | Serine/Threonine kinase domain protein |

| LTP1 | Lipid-transfer protein 1. |

| SERK3B | Somatic Embryogenesis Receptor-like Kinase 3B |

| BRI1 | Brassinosteroid LRR receptor kinase |

References

- Li, J.; Pu, L.; Han, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, R.; Xiang, Y. Soil salinization research in China: Advances and prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Mu, C. Effects of saline and alkaline stresses in varying temperature regimes on seed germination of Leymus chinensis from the Songnen Grassland of China. Grass Forage Sci. 2011, 66, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, K.; Zhang, T.; Tang, D.; Li, R.; Jia, S. Physiological responses of Goji berry (Lycium barbarum L.) to saline-alkaline soil from Qinghai region, China. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Wang, D. Effects of various salt-alkaline mixed stresses on Aneurolepidium chinense (Trin.) Kitag. Plant Soil 2005, 271, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zelm, E.; Zhang, Y.; Testerink, C. Salt tolerance mechanisms of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahanger, M.A.; Agarwal, R. Salinity stress induced alterations in antioxidant metabolism and nitrogen assimilation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) as influenced by potassium supplementation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkelish, A.A.; Soliman, M.H.; Alhaithloul, H.A.; El-Esawi, M.A. Selenium protects wheat seedlings against salt stress-mediated oxidative damage by up-regulating antioxidants and osmolytes metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 137, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahanger, M.A.; Qin, C.; Maodong, Q.; Dong, X.X.; Ahmad, P.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Zhang, L. Spermine application alleviates salinity induced growth and photosynthetic inhibition in Solanum lycopersicum by modulating osmolyte and secondary metabolite accumulation and differentially regulating antioxidant metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 144, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29–W37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, Q.-S. AtNHX5 and AtNHX6 control cellular K+ and pH homeostasis in Arabidopsis: Three conserved acidic residues are essential for K+ transport. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Fukada-Tanaka, S.; Inagaki, Y.; Saito, N.; Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Kusumi, T.; Iida, S. Genes encoding the vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger and flower coloration. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 42, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaxiola, R.A.; Rao, R.; Sherman, A.; Grisafi, P.; Alper, S.L.; Fink, G.R. The Arabidopsis thaliana proton transporters, AtNhx1 and Avp1, can function in cation detoxification in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, A.; Nakamura, A.; Tagiri, A.; Tanaka, H.; Miyao, A.; Hirochika, H.; Tanaka, Y. Function, intracellular localization and the importance in salt tolerance of a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter from rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorb, C.; Noll, A.; Karl, S.; Leib, K.; Yan, F.; Schubert, S. Molecular characterization of Na+/H+ antiporters (ZmNHX) of maize (Zea mays L.) and their expression under salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 162, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zuo, K.; Wu, W.; Song, J.; Sun, X.; Lin, J.; Li, X.; Tang, K. Molecular cloning and characterization of a new Na+/H+ antiporter gene from Brassica napus. DNA Seq. 2003, 14, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Mishra, S.; Pandey, B.; Singh, G. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the NHX gene family under salt stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, E.; Sari, U.; Tiryaki, I. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of Na+/H+ antiporter (NHX) genes in tomato under salt stress. Plant Direct 2023, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khare, T.; Joshi, S.; Kaur, K.; Srivastav, A.; Kumar, V. Genome-wide in silico identification and characterization of sodium-proton (Na+/H+) antiporters in Indica rice. Plant Gene 2021, 26, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-M.; Gu, C.-S.; Chen, F.-D.; Xu, Y.-C.; Liu, Z.-L. Salt Tolerance Verification of Lotus NnNHX1 in Transformed Tobacco. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2012, 39, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Apse, M.P.; Aharon, G.S.; Snedden, W.A.; Blumwald, E. Salt Tolerance Conferred by Overexpression of a Vacuolar Na+/H+ Antiport in Arabidopsis. Science 1999, 285, 1256–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.A.; Yang, G.D.; Meng, Q.W.; Zheng, C.C. The Cotton GhNHX1 Gene Encoding a Novel Putative Tonoplast Na+/H+ Antiporter Plays an Important Role in Salt Stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhai, H.; He, S.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Q. A vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene, IbNHX2, enhances salt and drought tolerance in transgenic sweetpotato. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 201, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apse, M.P.; Blumwald, E. Na+ transport in plants. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 2247–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumwald, E. Sodium transport and salt tolerance in plants. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000, 12, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeeson, V.; Kumari, K.; Pulipati, S.; Parida, A.; Venkataraman, G. Expression of wild rice Porteresia coarctata PcNHX1 antiporter gene (PcNHX1) in tobacco controlled by PcNHX1 promoter (PcNHX1p) confers Na+-specific hypocotyl elongation and stem-specific Na+ accumulation in transgenic tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 139, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, C.A.; Yong, M.-T.; Zhou, M.; Venkataraman, G.; Shabala, L.; Holford, P.; Shabala, S.; Chen, Z.-H. Evolutionary significance of NHX family and NHX1 in salinity stress adaptation in the genus oryza. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanroj, S.; Wang, G.; Venema, K.; Zhang, M.W.; Delwiche, C.F.; Sze, H. Conserved and diversified gene families of monovalent cation/H+ antiporters from algae to flowering plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassil, E.; Coku, A.; Blumwald, E. Cellular ion homeostasis: Emerging roles of intracellular NHX Na+/H+ antiporters in plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 5727–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujii, M.; Tanudjaja, E.; Uozumi, N. Diverse physiological functions of cation proton antiporters across bacteria and plant cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linde-Laursen, I.; von Bothmer, R. Giemsa C-banded karyotypes of two subspecies of Hordeum brevisubulatum from China. Plant Syst. Evol. 1984, 145, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Lester, D. Screening wild Hordeum species for resistance to Russian wheat aphid. Cereal Res. Commun. 1990, 18, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, X.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Du, Q.; Li, R. The specific HbHAK2 promoter from halophytic Hordeum brevisubulatum regulates root development under salt stress. Agric. Commun. 2024, 2, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassil, E.; Tajima, H.; Liang, Y.C.; Ohto, M.A.; Ushijima, K.; Nakano, R.; Esumi, T.; Coku, A.; Belmonte, M.; Blumwald, E. The Arabidopsis Na+/H+ antiporters NHX1 and NHX2 control vacuolar pH and K+ homeostasis to regulate growth, flower development, and reproduction. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3482–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J.M.; Cubero, B.; Quintero, L.F.J. Alkali cation exchangers: Roles in cellular homeostasis and stress tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 1181–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, A.; Nakamura, A.; Hara, N.; Toki, S.; Tanaka, Y. Molecular and functional analyses of rice NHX-type Na+/H+ antiporter genes. Planta 2011, 233, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Song, X.; Jiang, Y. Growth, ionic response, and gene expression of shoots and roots of perennial ryegrass under salinity stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidi, E.O.; Barragán, V.; Rubio, L.; El-Hamdaoui, A.; Pardo, J.M. The AtNHX1 exchanger mediates potassium compartmentation in vacuoles of transgenic tomato. Plant J. 2010, 61, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Kunz, H.H.; Schroeder, J.I.; Kemp, G.; Young, H.S.; Neuhaus, H.E. Decreased capacity for sodium export out of Arabidopsis chloroplasts impairs salt tolerance, photosynthesis and plant performance. Plant J. 2014, 78, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, M.D.L.; Masuda, S. Chloroplast pH homeostasis for the regulation of photosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 919896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Guo, Y.; Song, M.; Liu, L.; Xue, H.; Dai, H.; Zhang, Z. Dual role of MdSND1 in the biosynthesis of lignin and in signal transduction in response to salt and osmotic stress in apple. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Ali, A.; Yun, D.-J. Arabidopsis NHX transporters: Sodium and potassium antiport mythology and sequestration during ionic stress. J. Plant Biol. 2018, 61, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, F.; Horie, T. A conserved primary salt tolerance mechanism mediated by HKT transporters: A mechanism for sodium exclusion and maintenance of high K+/Na+ ratio in leaves during salinity stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-X.; Blumwald, E. Transgenic salt-tolerant tomato plants accumulate salt in foliage but not in fruit. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Guo, C.; Li, X.; Duan, W.; Ma, C.; Zhao, M.; Gu, J.; Du, X.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, K. Overexpression of TaNHX3, a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene in wheat, enhances salt stress tolerance in tobacco by improving related physiological processes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 76, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.K.; Joshi, M.; Mishra, A.; Jha, B. Ectopic expression of SbNHX1 gene in transgenic castor (Ricinus communis L.) enhances salt stress by modulating physiological process. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2015, 122, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.M.; Oliveira, M.M.; Saibo, N.J. Regulation of Na+ and K+ homeostasis in plants: Towards improved salt stress tolerance in crop plants. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2017, 40, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S. The CBL-CIPK network in plant calcium signaling. Trends Plant Sci 2009, 14, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y.H.; Kim, K.-N.; Pandey, G.K.; Gupta, R.; Grant, J.J.; Luan, S. CBL1, a calcium sensor that differentially regulates salt, drought, and cold responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1833–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Mo, Z.; Yuan, G.; Xiang, H.; Visser, R.G.; Bai, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Q.; van der Linden, C.G. The CBL-CIPK network is involved in the physiological crosstalk between plant growth and stress adaptation. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 3012–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, Q.; Fang, Y.; Huang, P.; Ju, C.; Wang, C. The CBL1/9-CIPK1 calcium sensor negatively regulates drought stress by phosphorylating the PYLs ABA receptor. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobylińska, A.; Posmyk, M.M. Melatonin restricts Pb-induced PCD by enhancing BI-1 expression in tobacco suspension cells. Biometals 2016, 29, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamoto, S.; Yabe, I.; Uozumi, N. Electrophysiological properties of NtTPK1 expressed in yeast tonoplast. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008, 72, 2785–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ni, R.; Yang, S.; Pu, Y.; Qian, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y. Functional characterization of the Stipa purpurea P5CS gene under drought stress conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soostani, S.B.; Ranjbar, M.; Memarian, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Yaghini, Z. Investigating the effect of chitosan on the expression of P5CS, PIP, and PAL genes in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) under salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.T.; Santos, S.P.; Rosa, M.G.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Abreu, I.A.; Frazao, C.; Romão, C.V. Expression, purification and crystallization of MnSOD from Arabidopsis thaliana. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2014, 70, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Si, H. Potato Stu-miR398b-3p negatively regulates Cu/Zn-SOD response to drought tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayengwa, R.; Westenskow, S.R.; Peng, H.; Hulbert, A.K.; Neff, M.M. Genetic Interactions Between BEN1-and Cytochrome P450-Mediated Brassinosteroid Inactivation. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancín, M.; Fernández-San Millán, A.; Larraya, L.; Morales, F.; Veramendi, J.; Aranjuelo, I.; Farran, I. Overexpression of thioredoxin m in tobacco chloroplasts inhibits the protein kinase STN7 and alters photosynthetic performance. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhot, N.; Gomes, E.; Milat, M.-L.; Ponchet, M.; Marion, D.; Lequeu, J.; Delrot, S.; Coutos-Thévenot, P.; Blein, J.-P. Modulation of the biological activity of a tobacco LTP1 by lipid complexation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 5047–5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nietzschmann, L.; Gorzolka, K.; Smolka, U.; Matern, A.; Eschen-Lippold, L.; Scheel, D.; Rosahl, S. Early Pep-13-induced immune responses are SERK3A/B-dependent in potato. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Oh, E.-S.; Min, H.; Chae, W.B.; Mandadi, K.K.; Oh, M.-H. Role of tyrosine autophosphorylation and methionine residues in BRI1 function in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Genom. 2022, 44, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.S.; Chen, Y.C.; Lu, C.H.; Hwang, J.K. Prediction of protein subcellular localization. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2006, 64, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Gattiker, A.; Hoogland, C.; Ivanyi, I.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Zong, W.; Li, X.; Ning, J.; Hu, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Xiong, L. The SNAC1-targeted gene OsSRO1c modulates stomatal closure and oxidative stress tolerance by regulating hydrogen peroxide in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leon, J.A.D.; Borges, C.R. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress in Biological Samples Using the Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances Assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 10.3791/61122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, Y. Reprint of: Generation of superoxide radical during autoxidation of hydroxylamine and an assay for superoxide dismutase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 726, 109247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozovskaya, E.; Vartanyan, L. Superoxide dismutase: Determination of activity by inhibition of photosensitized chemiluminescence of glycyltryptophan. Biochem. Biokhimiia 2000, 65, 599–603. [Google Scholar]

- Sailaja, K.; Shivaranjani, V.L.; Poornima, H.; Rahamathulla, S.; Devi, K.L. Protective effect of Tribulus terrestris L. fruit aqueous extracton lipid profile and oxidative stress in isoproterenol induced myocardial necrosis in male albino Wistar rats. EXCLI J. 2013, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Yang, M.; Zhao, W.; Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Tuluhong, M.; Wang, B.; Zheng, S.; Cui, G. Cloning and Functional Verification of Salt Tolerance Gene HbNHX2 in Hordeum brevisubulatum. Plants 2025, 14, 3658. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233658

Zhang M, Yang M, Zhao W, Yin H, Zhang X, Li B, Tuluhong M, Wang B, Zheng S, Cui G. Cloning and Functional Verification of Salt Tolerance Gene HbNHX2 in Hordeum brevisubulatum. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3658. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233658

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Mingzhi, Mei Yang, Wenjie Zhao, Hang Yin, Xinyi Zhang, Bing Li, Muzhapaer Tuluhong, Baiji Wang, Shanshui Zheng, and Guowen Cui. 2025. "Cloning and Functional Verification of Salt Tolerance Gene HbNHX2 in Hordeum brevisubulatum" Plants 14, no. 23: 3658. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233658

APA StyleZhang, M., Yang, M., Zhao, W., Yin, H., Zhang, X., Li, B., Tuluhong, M., Wang, B., Zheng, S., & Cui, G. (2025). Cloning and Functional Verification of Salt Tolerance Gene HbNHX2 in Hordeum brevisubulatum. Plants, 14(23), 3658. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233658