Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Appearance and Cell Development Characteristics of Blueberry Fruit

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on Blueberry Fruit

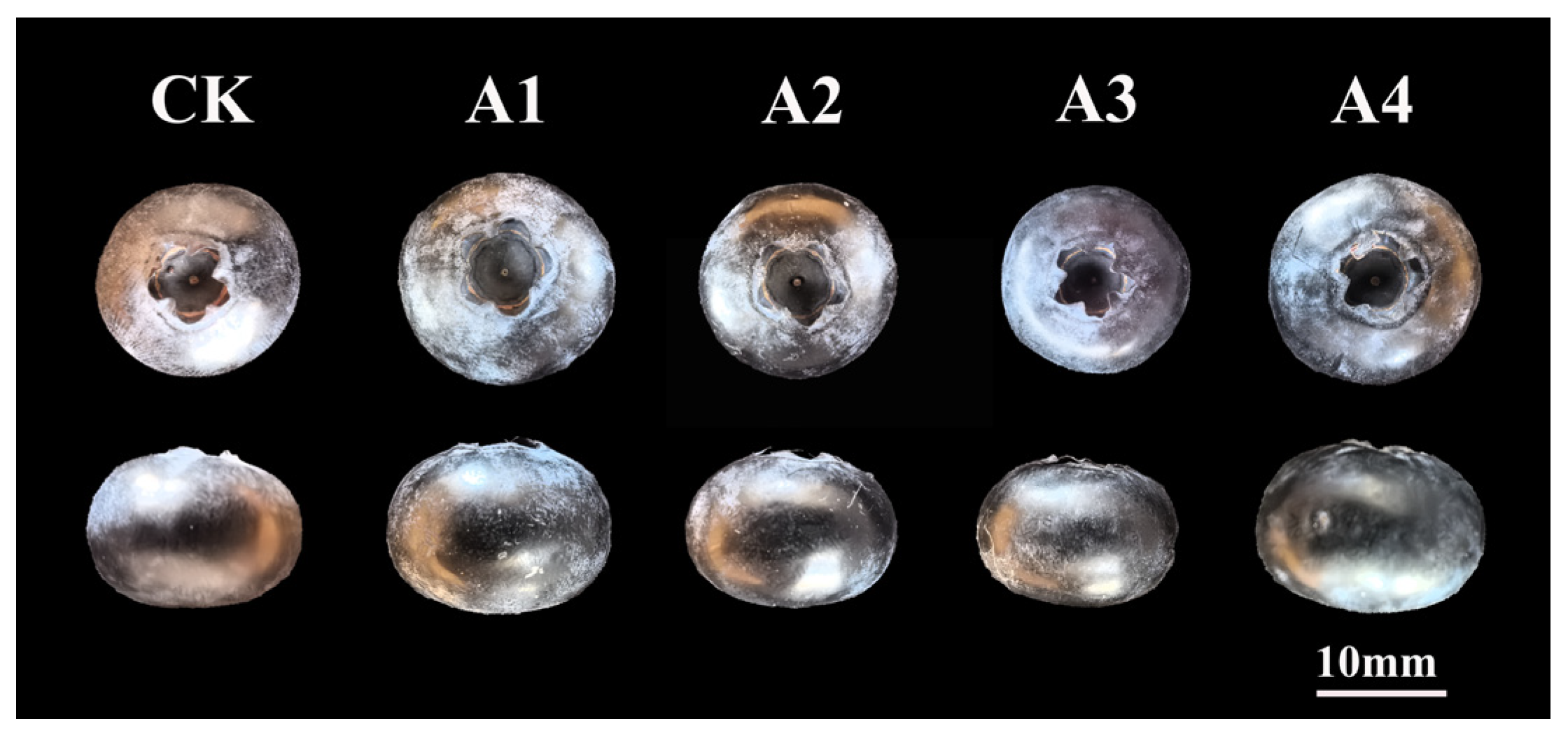

2.1.1. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on Fruit and Seed Development of Blueberry

2.1.2. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Size of Blueberry Fruit

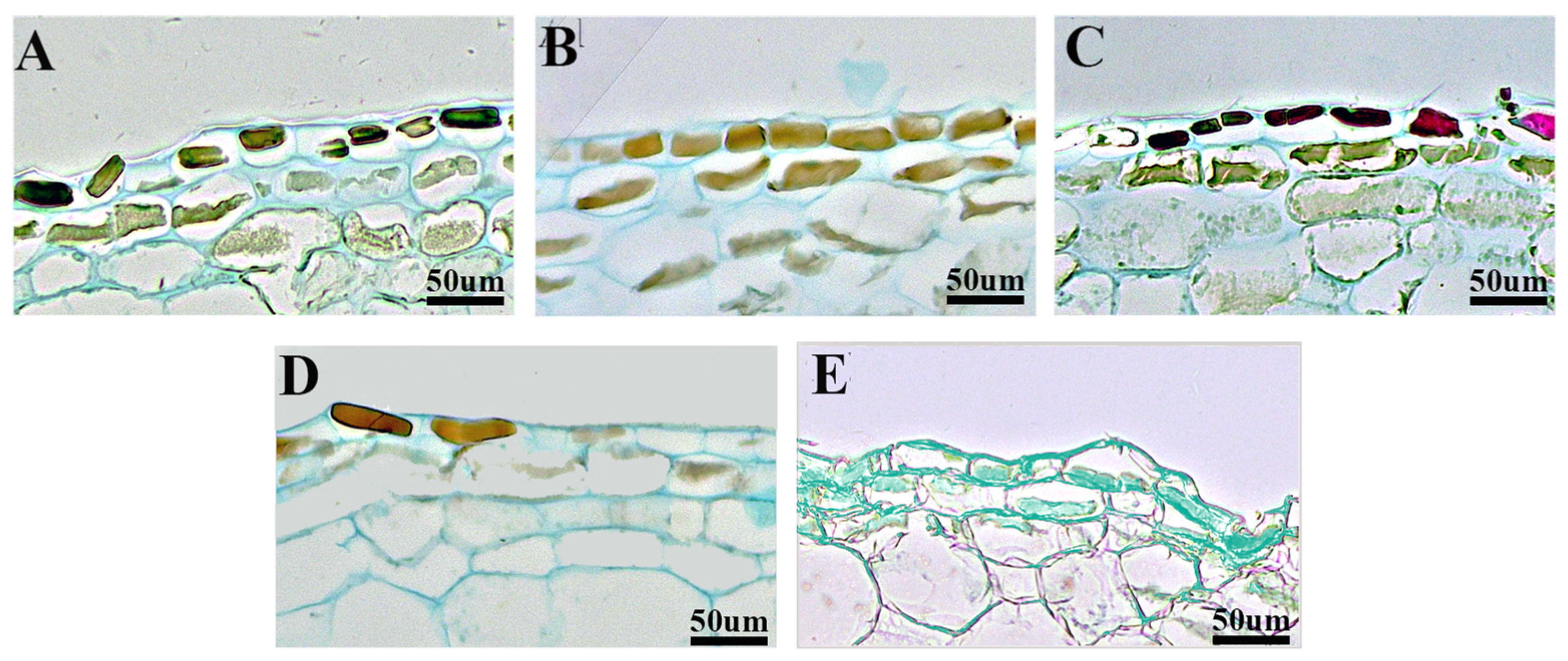

2.2. Observation of Epidermal Cells Under Different Pollination Treatments

2.3. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Size of Mesocarp Cells in Blueberry Fruit

2.3.1. Observation of Mesocarp Cells Under Different Pollination Treatments

2.3.2. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Size of Outer Mesocarp Cells

2.3.3. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on Cell Size in the Middle of Mesocarp

2.3.4. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on Cell Size in Inner Mesocarp

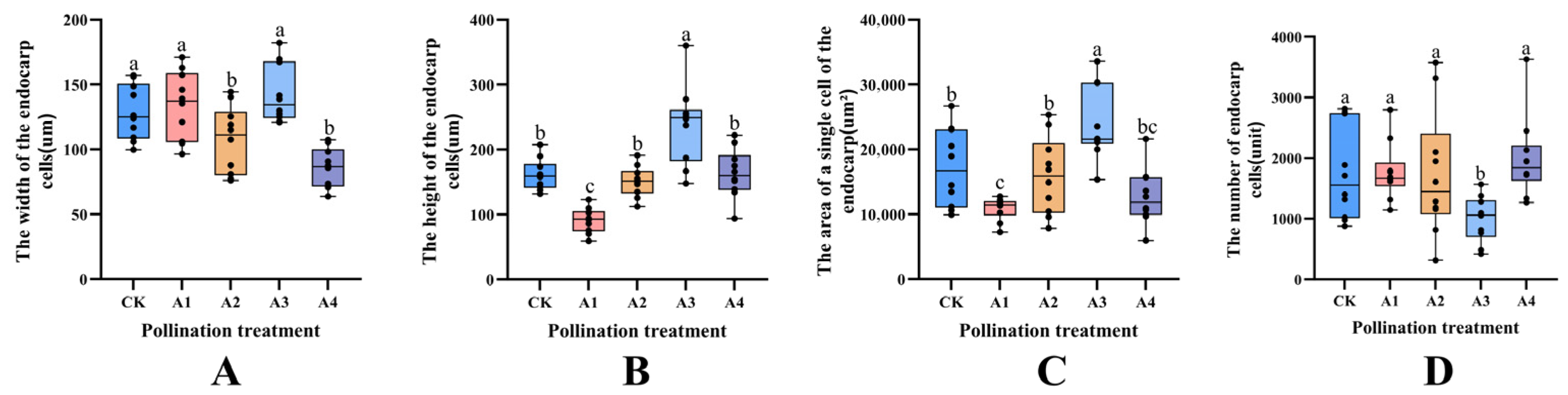

2.4. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on Cell Size of Blueberry Endocarp

2.5. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Correlation Between Blueberry Fruit Cells and Fruit Morphological Indexes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Test Sites and Plant Materials

4.2. Pollen Collection and Pollination

4.3. Study on the Blueberry Fruit Development Under Different Pollination Treatments

4.4. Study on the Cell Characterization of Lingonberry Fruit Under Different Pollination Treatments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saad, N.; Olmstead, J.W.; Jones, J.B.; Varsani, A.; Harmon, P.F. Known and New Emerging Viruses Infecting Blueberry. Plants 2021, 10, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbor, D.T.; Atemlefac, D.; Eboh, K.S.; Morara, C.N.; Dohnji, J.D. Impact of Natural and Hand-Assisted Pollination on Cucumber Fruit and Seed Yield. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2022, 9, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Tarafdar, A.; Chaurasia, D.; Singh, A.; Bhargava, P.C.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Ni, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Blueberry Fruit Valorization and Valuable Constituents: A Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 381, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrol, D.P. Pollination Biology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. A Novel Mechanism for Xenia? HortScience 2008, 43, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.d.A.; Williamson, J.G.; Olmsteade, J.W.; Lyrene, P.M. Reproductive Growth and Development of Blueberry. EDIS 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupton, C.L. Evidence of Xenia in Blueberry. Acta Hortic. 1997, 446, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlenfeldt, M.K. Self- and Cross-Fertility in Recently Released Highbush Blueberry Cultivars. HortScience 2001, 36, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupton, C.L. Effect of Pollen Source on Fruit Characteristics of Low-Chilling Highbush Type Blueberries. HortScience 1984, 19, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, D.J.; Lyrene, P.M. Effects of Self-Pollination and Cross-Pollination of Vaccinium Darrowii (Ericaceae) and Other Low-Chill Blueberries. HortScience 2009, 44, 1538–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupton, C.L.; Spiers, J.M. Interspecific and Intraspecific Pollination Effects in Rabbiteye and Southern Highbush Blueberry. HortScience 1994, 29, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, S.K.; Olmstead, J.W. Impact of Cross- and Self-Pollination on Fruit Set, Fruit Size, Seed Number, and Harvest Timing Among 13 Southern Highbush Blueberry Cultivars. HortTechnology 2016, 26, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cong, P.; He, J.; Bu, H.; Qin, S.; Lyu, D. Differential Pulp Cell Wall Structures Lead to Diverse Fruit Textures in Apple (Malus Domestica). Protoplasma 2022, 259, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.; Alspach, P.; Scalzo, J.; Meekings, J. Pollination of ‘Hortblue Petite’ Blueberry: Evidence of Metaxenia in a New Ornamental Home-Garden Cultivar. HortScience 2011, 46, 1468–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; He, L.; Guo, L.; Li, C.; Li, X.-X.; et al. Light Signal Regulates Endoreduplication and Tomato Fruit Expansion through the SlPIF1a-SlTLFP8-SlCDKB2 Module. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2404445122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W.; Fan, G.; Zhang, S. Relationship between Fruit Growth and Development and Microstructural Changes in Six European Plum Varieties. J. Fruit Sci. 2025, 42, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaudin, J.-P.; Deluche, C.; Cheniclet, C.; Chevalier, C.; Frangne, N. Cell Layer-Specific Patterns of Cell Division and Cell Expansion during Fruit Set and Fruit Growth in Tomato Pericarp. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1613–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wu, Z.; Sun, D.; Long, L.; Song, Q.; Gao, C. Cytological Characteristics of Blueberry Fruit Development. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Khurana, A.D.; Sharma, A.K. Role of Plant Hormones and Their Interplay in Development and Ripening of Fleshy Fruits. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 65, 4561–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, K.; Yamane, H.; Nishiyama, S.; Ebihara, S.; Matsuzaki, R.; Shoji, M.; Tao, R. Insights into the Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Highbush Blueberry Fruit Growth Affected by the Pollen Source. Hort. J. 2022, 91, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Effects of Exogenous Polyamines and Their Inhibitors on the Growth and Development of Blueberry Fruit. GuiZhou University 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Kurahashi, W.; Yanai, M.; Wakasa, Y.; Satoh, T. Involvement of Cell Proliferation and Cell Enlargement in Increasing the Fruit Size of Malus Species. Sci. Hortic. 2005, 105, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, J.; Dang, M.; Yang, H.; Fan, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Comparative the Anatomy of the Fruit between a New Apple Cultivar ‘Ruiyang’ and Its Parents. J. Fruit Sci. 2018, 35, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, S.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Fan, B.; Wang, P.; Gao, Y.; Ye, Z.; et al. Exploring the Influence of a Single-Nucleotide Mutation in EIN4 on Tomato Fruit Firmness Diversity through Fruit Pericarp Microstructure. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2379–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, J.W.; Hewett, E.W.; Hertog, M.L.A.T.M.; Harker, F.R. Harvest Date and Fruit Size Affect Postharvest Softening of Apple Fruit. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2002, 77, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Li, Z.; Wegner, G.; Zude-Sasse, M. Effect of Cell Size Distribution on Mechanical Properties of Strawberry Fruit Tissue. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaker, K.M.; Olmstead, J.W. Stone Cell Frequency and Cell Area Variation of Crisp and Standard Texture Southern Highbush Blueberry Fruit. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2014, 139, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leposavić, A.; Đorđević, M.; Cerović, R.; Radičević, S.; Đurović, D. Fertilization Biology of ‘Reka’ Highbush Blueberry. Acta Hortic. 2021, 1308, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; He, S.; Yu, H. Blue Berries and Cranberries. China Agric. Publ. House 2001, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Luby, J.J.; Ballington, J.R.; Draper, A.D.; Pliszka, K.; Austin, M.E. Blueberries and Cranberries (Vaccinium). Acta Hortic. 1991, 290, 393–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, I.V.; Aalders, L.E. Blomidon Lowbush Blueberry. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1982, 62, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Draper, A.; Vorsa, N.; Galleta, G.; Jelenkovic, G.; Ehlenfeldt, M. “Toro” Highbush Blueberry. Fruit Var. J. 1995, 49, 99–100. [Google Scholar]

| Pollinating Treatments | Berry Bloom | Scar at the Base of Berry Size | Berry Status of Calyx | Berry Depth of Eye Basin | Berry Width of Eye Basin | Number of Seed | Seed Size | Percentage of Fertile Fruit (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | ** | - | ** | * | ** | * | ** | 76.09 d |

| A1 | ** | * | ** | * | * | - | ** | 82.44 c |

| A2 | ** | - | ** | * | * | - | ** | 82.95 c |

| A3 | ** | - | ** | * | ** | * | ** | 90.67 a |

| A4 | ** | - | ** | * | ** | - | ** | 84.4 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, C.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Li, K.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Appearance and Cell Development Characteristics of Blueberry Fruit. Plants 2025, 14, 3341. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213341

Lu C, Liu D, Liu J, Li K, Wang X, Li J, Wu L, Wang Y, Li Y. Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Appearance and Cell Development Characteristics of Blueberry Fruit. Plants. 2025; 14(21):3341. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213341

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Chunze, Dian Liu, Jiayi Liu, Ke Li, Xinchun Wang, Jinying Li, Lin Wu, Ying Wang, and Yanan Li. 2025. "Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Appearance and Cell Development Characteristics of Blueberry Fruit" Plants 14, no. 21: 3341. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213341

APA StyleLu, C., Liu, D., Liu, J., Li, K., Wang, X., Li, J., Wu, L., Wang, Y., & Li, Y. (2025). Effects of Different Pollination Treatments on the Appearance and Cell Development Characteristics of Blueberry Fruit. Plants, 14(21), 3341. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213341