Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Forest Diversity and Structure in Green Areas of Santiago de Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

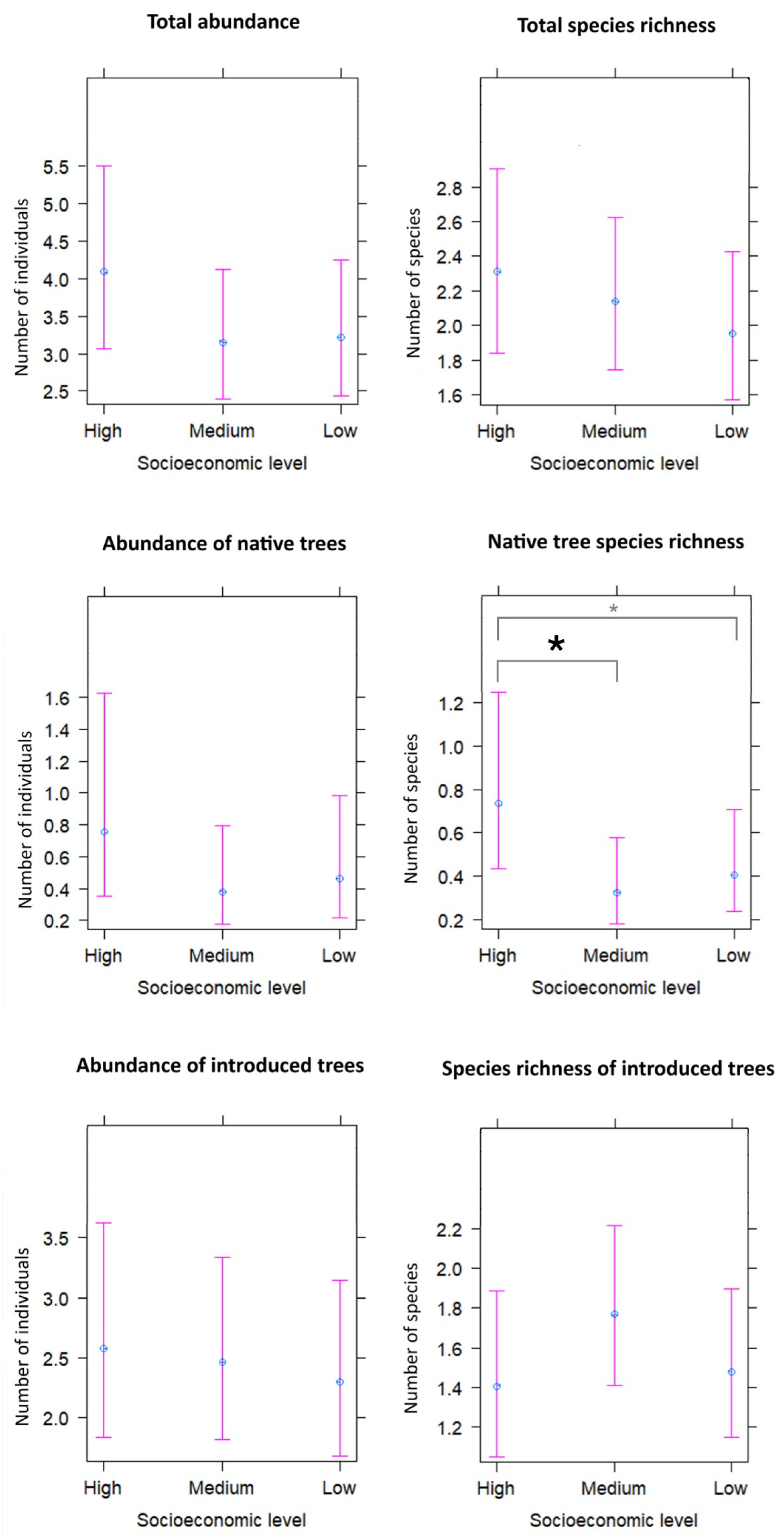

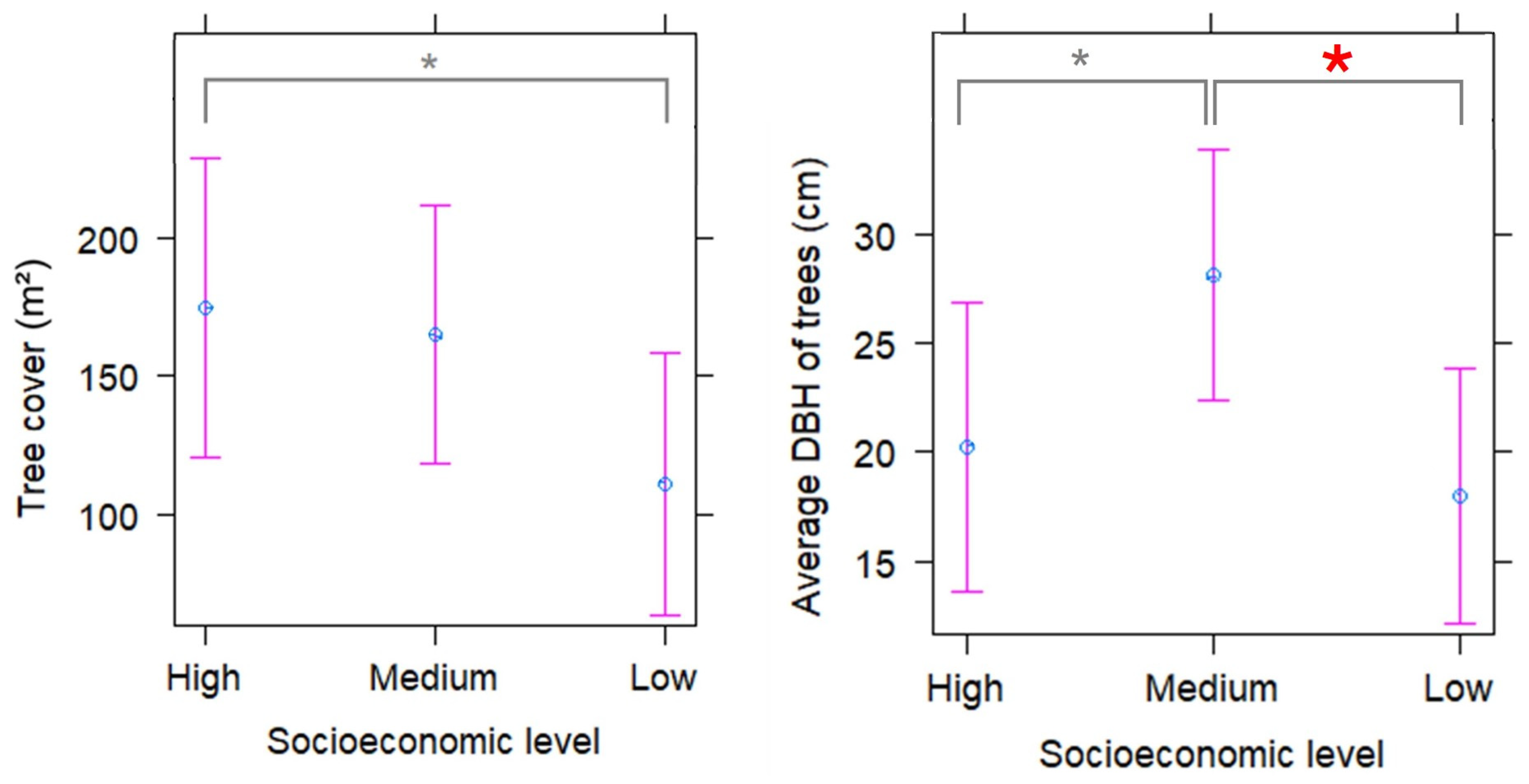

2. Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Luxury Effect: Abundance and Tree Diversity

3.2. Differential Effect According to the Origin of the Species

3.3. Tree Cover and DBH Averages

3.4. Urban Tree Composition

3.5. Recommendations for Green Areas

4. Materials and Methods

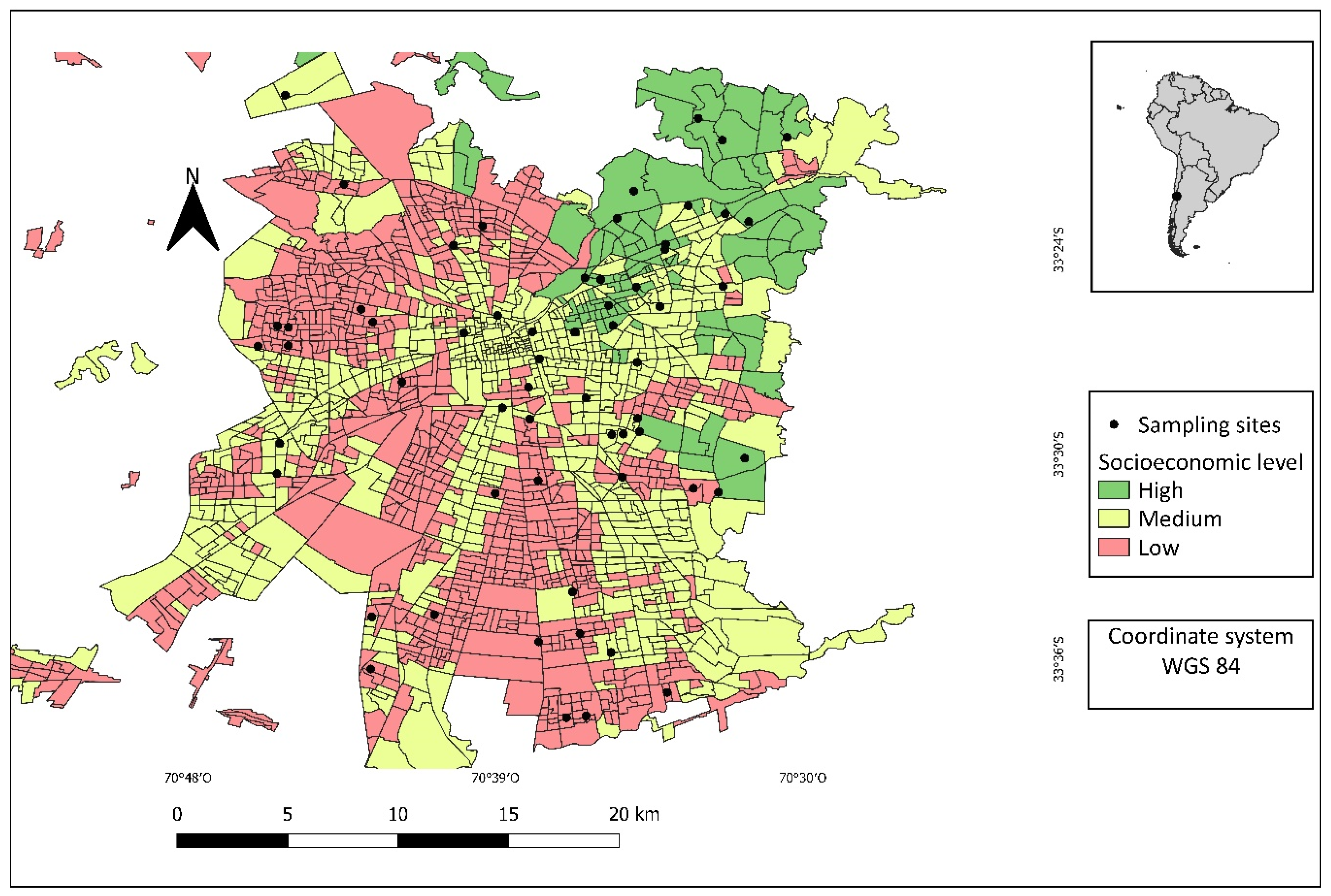

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Selection of Sampling Sites

4.3. Tree Sampling

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Local Common Name (Spanish) | Scientific Name and Author | Abundance | Relative Abundance (%) | Origin | Presence in Green Areas | Presence in Green Areas (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Espino | Vachellia caven (Molina) Seigler & Ebinger | 49 | 10.6% | Native | 5 | 8.3% |

| Quillay | Quillaja saponaria Molina | 47 | 10.2% | Native | 21 | 35.0% |

| Liquidámbar | Liquidambar styraciflua L. | 35 | 7.6% | Introduced | 13 | 21.7% |

| Ligustro | Ligustrum lucidum W.T.Aiton | 22 | 4.8% | Introduced | 6 | 10.0% |

| Jacarandá | Jacaranda mimosifolia D.Don | 18 | 3.9% | Introduced | 7 | 11.7% |

| Pimiento | Schinus areira L. | 15 | 3.2% | Native | 8 | 13.3% |

| Aromo australiano | Acacia melanoxylon R.Br. | 13 | 2.8% | Introduced | 4 | 6.7% |

| Tulipífero de Virginia | Liriodendron tulipifera L. | 13 | 2.8% | Introduced | 6 | 10.0% |

| Fresno norteño | Fraxinus excelsior L. | 12 | 2.6% | Introduced | 7 | 11.7% |

| Olmo común | Ulmus minor Mill. | 12 | 2.6% | Introduced | 4 | 6.7% |

| Maitén | Maytenus boaria Molina | 11 | 2.4% | Native | 6 | 10.0% |

| Acacia de tres espinas | Gleditsia triacanthos L. | 10 | 2.2% | Introduced | 7 | 11.7% |

| Roble español | Quercus falcata Michx. | 10 | 2.2% | Introduced | 6 | 10.0% |

| Árbol botella | Brachychiton populneus (Schott & Endl.) R.Br. | 9 | 1.9% | Introduced | 5 | 8.3% |

| Falso plátano | Acer pseudoplatanus L. | 8 | 1.7% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Eucalipto rojo | Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | 8 | 1.7% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Nogal del Japón | Ginkgo biloba L. | 8 | 1.7% | Introduced | 5 | 8.3% |

| Árbol del paraíso | Melia azedarach L. | 8 | 1.7% | Introduced | 5 | 8.3% |

| Plátano híbrido | Platanus × hispanica Mill. ex Münchh. | 8 | 1.7% | Introduced | 4 | 6.7% |

| Pino australiano | Casuarina cunninghamiana Miq. | 7 | 1.5% | Introduced | 4 | 6.7% |

| Álamo negro | Populus deltoides W.Bartram ex Marshall | 7 | 1.5% | Introduced | 5 | 8.3% |

| Litre | Lithraea caustica (Molina) Hook. & Arn. | 6 | 1.3% | Native | 1 | 1.7% |

| Magnolia | Magnolia grandiflora L. | 6 | 1.3% | Introduced | 5 | 8.3% |

| Granada | Punica granatum L. | 6 | 1.3% | Introduced | 4 | 6.7% |

| Falsa acacia | Robinia pseudoacacia L. | 6 | 1.3% | Introduced | 3 | 5.0% |

| Pezuña de vaca | Bauhinia forficata Link | 5 | 1.1% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Cedrus sp | Cedrus sp. Mill. | 5 | 1.1% | Introduced | 5 | 8.3% |

| Peumo | Cryptocarya alba (Molina) Looser | 5 | 1.1% | Native | 5 | 8.3% |

| Espinillo | Parkinsonia aculeata L. | 5 | 1.1% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Sauce llorón | Salix babylonica L. | 5 | 1.1% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Ciprés calvo | Taxodium distichum (L.) Rich. | 5 | 1.1% | Introduced | 3 | 5.0% |

| Pino bunya | Araucaria bidwillii Hook. | 4 | 0.9% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Eucalipto blanco | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | 4 | 0.9% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Ciruelo rojo | Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. | 4 | 0.9% | Introduced | 4 | 6.7% |

| Roble albar | Quercus robur L. | 4 | 0.9% | Introduced | 3 | 5.0% |

| Alcornoque mediterráneo | Quercus suber L. | 4 | 0.9% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Árbol de los dioses | Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | 3 | 0.6% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Lodón | Celtis australis L. | 3 | 0.6% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Patagua | Crinodendron patagua Molina | 3 | 0.6% | Native | 1 | 1.7% |

| Ceibo de monte | Erythrina falcata Benth. | 3 | 0.6% | Introduced | 3 | 5.0% |

| Roble australiano | Grevillea robusta A.Cunn. ex R.Br. | 3 | 0.6% | Introduced | 3 | 5.0% |

| Árbol de Júpiter | Lagerstroemia indica L. | 3 | 0.6% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Morera blanca | Morus alba L. | 3 | 0.6% | Introduced | 3 | 5.0% |

| Mayo | Sophora macrocarpa Sm. | 3 | 0.6% | Native | 1 | 1.7% |

| Acer negundo | Acer negundo L. | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Árbol de fuego | Brachychiton acerifolius (A.Cunn. ex G.Don) F.Muell. | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Olivo de Bohemia | Elaeagnus angustifolia L. | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Eucaliptus sp | Eucalyptus sp. L’Hér. | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Viscote negro | Parasenegalia visco (Lorentz ex Griseb.) Seigler & Ebinger | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Pinus sp | Pinus sp. L. | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Durazno | Prunus persica (L.) Batsch | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Tilo americano | Tilia americana L. | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Ulmus sp | Ulmus sp. L. | 2 | 0.4% | Introduced | 2 | 3.3% |

| Castaño de Indias | Aesculus hippocastanum L. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Pino del Paraná | Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Steud. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Pewén | Araucaria araucana (Molina) K.Koch | 1 | 0.2% | Native | 1 | 1.7% |

| Casuarina sp | Casuarina sp. L. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Árbol Indio | Catalpa bignonioides Walter | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Espino blanco | Crataegus monogyna Jacq. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Ciprés llorón | Cupressus funebris Endl. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Níspero japonés | Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Ceibo | Erythrina crista-galli L. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Laurel | Laurus nobilis L. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Mióporo | Myoporum laetum G.Forst. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Roble bur | Quercus macrocarpa Endl. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Quercus sp | Quercus sp. L. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Molle | Schinus latifolius (Gillies ex Lindl.) Engl. | 1 | 0.2% | Native | 1 | 1.7% |

| Árbol de las pagodas | Styphnolobium japonicum (L.) Schott | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Olmo péndulo | Ulmus glabra Huds. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

| Viburnum dulce | Viburnum odoratissimum Ker Gawl. | 1 | 0.2% | Introduced | 1 | 1.7% |

References

- Convention on Biological Diversity [CDB]. Cities and Biodiversity Outlook: Action and Policy: A Global Assessment of the Links between Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, D.; Dwyer, J.; Childs, G. Los beneficios y costos del enverdecimiento urbano. In Áreas Verdes Urbanas en Latinoamérica y el Caribe; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, M.; Barzetti, V.; Keipi, K.; Williams, J. Manejo de las Áreas verdes Urbanas: Documento de Buenas Prácticas; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, D.; Crane, D.; Stevens, J. Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Byrne, J.; Pickering, C. A systematic quantitative review of urban tree benefits, costs, and assessment methods across cities in different climatic zones. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanusi, R.; Johnstone, D.; May, P.; Livesley, S. Street orientation and side of the street greatly influence the microclimatic benefits street trees can provide in summer. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvey, A. Promoting and preserving biodiversity in the urban forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikin, K.; Le Roux, D.; Rayner, L.; Villaseñor, N.; Eyles, K.; Gibbons, P.; Lindenmayer, D. Key lessons for achieving biodiversity-sensitive cities and towns. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2015, 16, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor, N.; Truffello, R.; Reyes-Paecke, S. Greening at multiple scales promote biodiverse cities: A multi-scale assessment of drivers of Neotropical birds. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 66, 127394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor, N.; Muñoz-Pacheco, C.; Escobar, M.A.H. Opposite Responses of Native and Nonnative Birds to Socioeconomics in a Latin American City. Animals 2024, 14, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, R.; Irvine, K.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.; Gaston, K. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, L.; Zu Ermgassen, S.; Balmford, A.; White, M.; Weinstein, N. Is variety the spice of life? An experimental investigation into the effects of species richness on self-reported mental well-being. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.; Honold, J.; Cvejić, R.; Delshammar, T.; Hilbert, S.; Lafortezza, R.; Nastrand, M.; Nielsen, A.; Pintar, M.; Kowarik, I. Beyond green: Broad support for biodiversity in multicultural European cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 49, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methorst, J.; Bonn, A.; Marselle, M.; Böhning-Gaese, K.; Rehdanz, K. Species richness is positively related to mental health–a study for Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 211, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, D.; Gries, C.; Zhu, W.; Fagan, W.; Redman, C.; Grimm, N.; Nelson, A.; Martin, C.; Kinzig, A. Socioeconomics drive urban plant diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8788–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heynen, N.; Lindsey, G. Correlates of urban forest canopy cover: Implications for local public works. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2003, 8, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flocks, J.; Escobedo, F.; Wade, J.; Varela, S.; Wald, C. Environmental justice implications of urban tree cover in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Environ. Justice 2011, 4, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, M.; Dunn, R.; Trautwein, M. Biodiversity and socioeconomics in the city: A review of the luxury effect. Biol. Lett. 2018, 14, 20180082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbe, C.; Siebert, S.; Cilliers, S. Political legacy of South Africa affects the plant diversity patterns of urban domestic gardens along a socio-economic gradient. Sci. Res. Essays 2010, 5, 2900–2910. [Google Scholar]

- Maco, S.; McPherson, E. Assessing canopy cover over streets and sidewalks in street tree populations. J. Arboric. 2002, 28, 270–276. [Google Scholar]

- Breuste, J. Investigations of the urban street tree forest of Mendoza, Argentina. Urban Ecosyst. 2013, 16, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Nizamani, M.; Jim, C.; Qureshi, S.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, S.; Balfour, K.; Wang, H. Response of urban tree DBH to fast urbanization: Case of coastal Zhanjiang in south China. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenerette, G.; Miller, G.; Buyantuev, A.; Pataki, D.; Gillespie, T.; Pincetl, S. Urban vegetation and income segregation in drylands: A synthesis of seven metropolitan regions in the southwestern United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 044001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, K.; Fragkias, M.; Boone, C.; Zhou, W.; McHale, M.; Grove, J.; Cadenasso, M.L. Trees grow on money: Urban tree canopy cover and environmental justice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meineke, E.; Dunn, R.; Sexton, J.; Frank, S. Urban warming drives insect pest abundance on street trees. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reager, J.; Gardner, A.; Famiglietti, J.; Wiese, D.; Eicker, A.; Lo, M. A decade of sea level rise slowed by climate-driven hydrology. Science 2016, 351, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Parker, K.; Kalcounis-Rueppell, M. The luxury effect beyond cities: Bats respond to socioeconomic variation across landscapes. BMC Ecol. 2019, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzig, A.; Warren, P.; Martin, C.; Hope, D.; Katti, M. The effects of human socioeconomic status and cultural characteristics on urban patterns of biodiversity. Ecol. Soc. 2005, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.; Nowak, D.; Wagner, J.; De la Maza, C.; Rodríguez, M.; Crane, D.; Hernández, J. The socio-economics and management of Santiago de Chile’s public urban forests. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, J. The role of local government greening policies in the transition towards nature-based cities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 35, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, H.; Vásquez, A.; Fuentes, C.; Salgado, M.; Schmidt, A.; Banzhaf, E. Assessing urban environmental segregation (UES). The case of Santiago de Chile. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 23, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Barrera, F.; Reyes-Paecke, S.; Banzhaf, E. Indicators for green spaces in contrasting urban settings. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 62, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Maza, C.; Hernández, J.; Bown, H.; Rodríguez, M.; Escobedo, F. Vegetation diversity in the Santiago de Chile urban ecosystem. Arboric. J. 2002, 26, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, H.; Villaseñor, N. Twelve-year change in tree diversity and spatial segregation in the Mediterranean city of Santiago, Chile. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.; Finlayson, B.; McMahon, T. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, S.; Villaseñor, N. Inequities in urban tree care based on socioeconomic status. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 96, 128363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexia, T.; Vieira, J.; Príncipe, A.; Anjos, A.; Silva, P.; Lopes, N.; Pinho, P. Ecosystem services: Urban parks under a magnifying glass. Environ. Res. 2018, 160, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egas, C.; Naulin, P.; Préndez, M. Contaminación urbana por material particulado y su efecto sobre las características morfo-anatómicas de cuatro especies arbóreas de Santiago de Chile. Inf. Tecnológica 2018, 29, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borsdorf, A. Cómo modelar el desarrollo y la dinámica de la ciudad latinoamericana. EURE 2003, 29, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, F. Arquitectura del Paisaje en Chile; Ocho Libros Editores: Santiago, Chile, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, J.; Castro, S.; Reyes, M.; Tellier, S. Urban park area and age determine the richness of native and exotic plants in parks of a Latin American city: Santiago as a case study. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, P.; De la Barrera, F. Análisis de la estructura y de la composición del arbolado en parques del área metropolitana de Santiago. Chloris Chil. 2014, 17, 1. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, J. The World’s Urban Forests; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce-Donoso, M.; Vallejos-Barra, O.; Escobedo, F. Appraisal of urban trees using twelve valuation formulas and two appraiser groups. Arboric. Urban For. 2017, 43, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAF. Programa De Arborización + Árboles Para Chile; CONAF: Santiago, Chile, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, P. 84 Árboles para las Ciudades de Chile; Escuela de Ingeniería Forestal, Ediciones Universidad Mayor: Santiago, Chile, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- CONAF. Listado Viveros Forestales; CONAF: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- GBC Chile. Manual de Paisajismo Sustentable. Available online: https://www.chilegbc.cl/assets/images/documentos/Manual_Paisajismo_ChileGBC_final_2021%20(Interactivo%20Web).pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Ministerio de Obras Públicas. Manual de Manejo de Áreas Verdes Sostenible para Proyectos y Obras Concesionadas; Ministerio de Obras Públicas: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, M.; Vargas, M.; Allamand, N. Arbolado urbano desafíos y propuestas para la región metropolitana. Enel Distrib. 2022, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Sistema de Indicadores y Estándares de Desarrollo Urbano (SIEDU); Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Informe Anual. Medio Ambiente; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Garreaud, R.; Boisier, J.; Rondanelli, R.; Montecinos, A.; Sepúlveda, H.; Veloso-Aguila, D. The central Chile mega drought (2010–2018): A climate dynamics perspective. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Indicadores de Calidad de Plazas y Parques Urbanos en Chile; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, P.; Valenzuela, J.; Truffello, R.; Ulloa, J.; Matas, M.; Quintana, D. Un Modelo de Identificación de Requerimientos de Nueva Infraestructura Pública en Educación Básica; Ministerio de Educación: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Villaseñor, N.; Escobar, M. Linking Socioeconomics to Biodiversity in the City: The Case of a Migrant Keystone Bird Species. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 850065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GfK Chile. Estilo de Vida de los Nuevos Grupos Socioeconómicos de Chile. Available online: https://www.gfk.com/fileadmin/user_upload/country_one_pager/CL/GfK_GSE_190502_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bolker, B.; Brooks, M.; Clark, C.; Geange, S.; Poulsen, J.; Stevens, M.; White, J. Generalized linear mixed models: A practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A.; Baldini, A.; Guajardo, F. Árboles urbanos de Chile; CONAF: Santiago, Chile, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IPNI. International Plant Names Index. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries and Australian National Herbarium. Available online: http://www.ipni.org (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Municipalidad de Lo Barnechea. Manual de Especies Recomendadas y Arbolado Urbano; Municipalidad de Lo Barnechea: Santiago, Chile, 2022; Available online: https://lobarnechea.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Manual-de-especies-recomendadas-y-arbolado-urbano-21032022-.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2024. Available online: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Rodríguez, R.; Marticorena, C.; Alarcón, D.; Baeza, C.; Cavieres, L.; Finot, V.; Fuentes, N.; Kiessling, A.; Mihoc, M.; Pauchard, A.; et al. Catálogo de las plantas vasculares de Chile. Gayana Bot. 2018, 75, 1–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biblioteca Digital INFOR. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.infor.cl (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Darwinion. Available online: http://www.darwin.edu.ar (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Fundación Philippi. Available online: https://fundacionphilippi.cl (accessed on 21 November 2022).

| Total | Socioeconomic Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | ||

| Number of green areas sampled | 60 | 17 | 22 | 21 |

| Number of plots sampled | 117 | 32 | 43 | 42 |

| Number of plots with trees | 109 | 30 | 41 | 38 |

| Number of trees | 463 | 147 | 156 | 160 |

| Number of native trees | 141 | 60 | 34 | 47 |

| Number of introduced trees | 322 | 87 | 122 | 113 |

| Number of trees/plot (mean ± SE) | 3.96 ± 3.04 | 4.59 ± 3.40 | 3.63 ± 2.76 | 3.81 ± 2.95 |

| Number of native trees/plot (mean ± SE) | 1.21 ± 2.05 | 1.88 ± 2.63 | 0.79 ± 1.32 | 1.12 ± 2.04 |

| Number of introduced trees/plot (mean ± SE) | 2.75 ± 2.48 | 2.72 ± 2.67 | 2.84 ± 2.29 | 2.69 ± 2.51 |

| Socioeconomic Level | Number of Plots | Sampled Area (ha) | Total Tree Density (ind/ha) | Native Tree Density (ind/ha) | Introduced Tree Density (ind/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 32 | 1.22 | 120.85 | 49.32 | 71.52 |

| Medium | 43 | 1.63 | 95.44 | 20.8 | 74.64 |

| Low | 42 | 1.6 | 100.22 | 29.44 | 70.78 |

| Response Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total abundance | Intercept (Socioeconomic: High) | 1.41 | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic: Medium | −0.27 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| Socioeconomic: Low | −0.24 | 0.20 | 0.23 | |

| Total species richness | Intercept (Socioeconomic: High) | 0.84 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic: Medium | −0.08 | 0.16 | 0.62 | |

| Socioeconomic: Low | −0.17 | 0.16 | 0.29 | |

| Abundance of native trees | Intercept (Socioeconomic: High) | −0.28 | 0.39 | 0.47 |

| Socioeconomic: Medium | −0.70 | 0.51 | 0.17 | |

| Socioeconomic: Low | −0.50 | 0.51 | 0.33 | |

| Native tree species richness | Intercept (Socioeconomic: High) | −0.31 | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| Socioeconomic: Medium | −0.83 | 0.37 | 0.03 | |

| Socioeconomic: Low | −0.59 | 0.35 | 0.09 | |

| Abundance of introduced trees | Intercept (Socioeconomic: High) | 0.85 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic: Medium | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.97 | |

| Socioeconomic: Low | −0.06 | 0.23 | 0.79 | |

| Species richness of introduced trees | Intercept (Socioeconomic: High) | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| Socioeconomic: Medium | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.22 | |

| Socioeconomic: Low | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.80 |

| Response Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree cover (m2) | Intercept (Socioeconomic: High) | 174.63 | 27.19 | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic: Medium | −9.36 | 35.96 | 0.8 | |

| Socioeconomic: Low | −63.72 | 36.17 | 0.08 | |

| Average tree DBH | Intercept (Socioeconomic: High) | 20.23 | 3.35 | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic: Medium | 7.85 | 4.44 | 0.08 | |

| Socioeconomic: Low | −2.21 | 4.47 | 0.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guevara, B.R.; Uribe, S.V.; de la Maza, C.L.; Villaseñor, N.R. Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Forest Diversity and Structure in Green Areas of Santiago de Chile. Plants 2024, 13, 1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13131841

Guevara BR, Uribe SV, de la Maza CL, Villaseñor NR. Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Forest Diversity and Structure in Green Areas of Santiago de Chile. Plants. 2024; 13(13):1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13131841

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuevara, Brian R., Sandra V. Uribe, Carmen L. de la Maza, and Nélida R. Villaseñor. 2024. "Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Forest Diversity and Structure in Green Areas of Santiago de Chile" Plants 13, no. 13: 1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13131841

APA StyleGuevara, B. R., Uribe, S. V., de la Maza, C. L., & Villaseñor, N. R. (2024). Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Forest Diversity and Structure in Green Areas of Santiago de Chile. Plants, 13(13), 1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13131841