What Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Are Available under the Plant Treaty and Where Is This Information?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

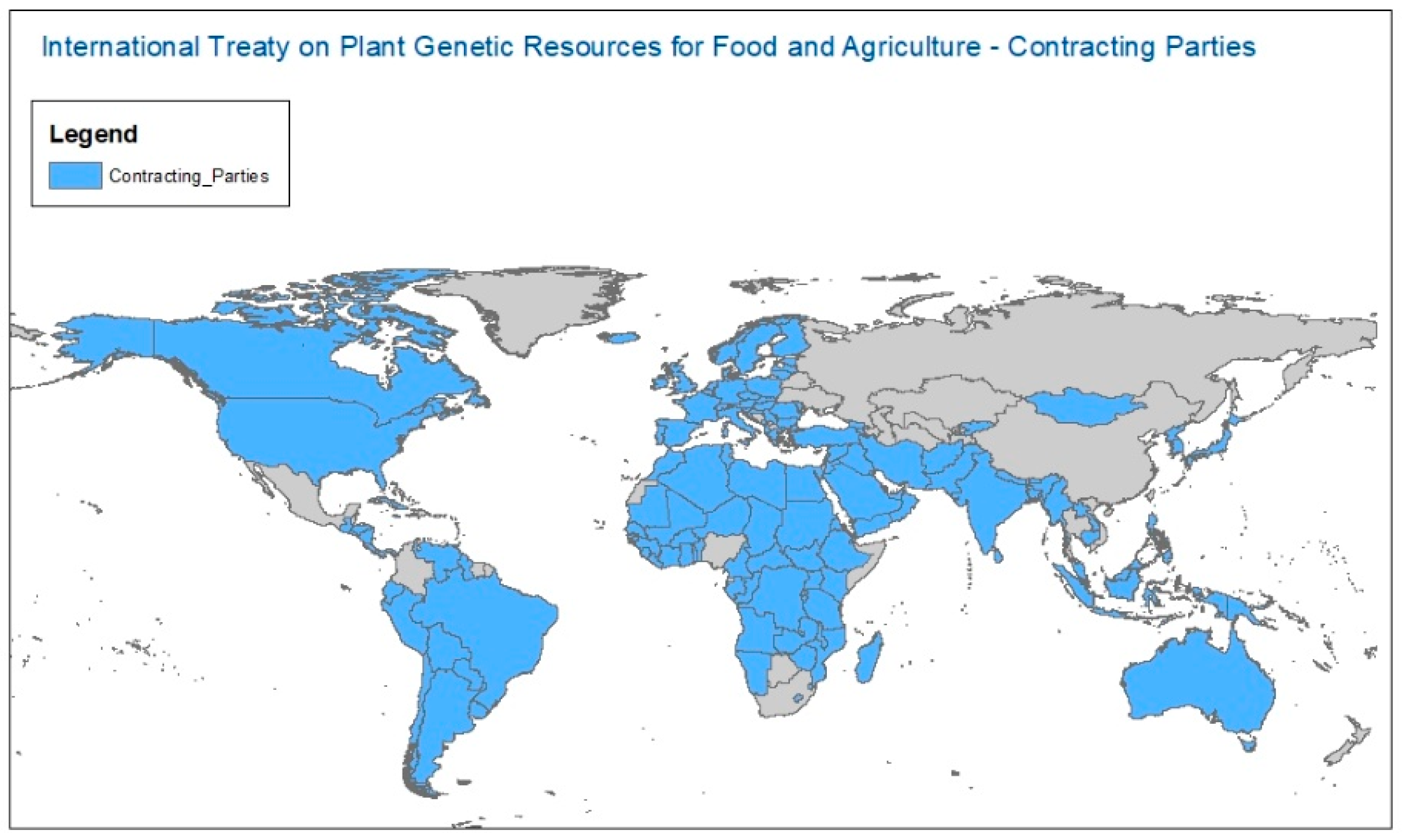

- PGRFA that are “under the management and control” of the Contracting Parties (i.e., national governments) and “in the public domain”. These PGRFA are automatically included in the Multilateral System when a Contracting Party ratifies or accedes to the Plant Treaty.

- PGRFA that are voluntarily included by “natural or legal persons”. Since only materials managed and controlled by national governments are automatically included, the Multilateral System depends on additional materials being voluntarily included by national governments (i.e., non-Annex I crops), companies, farmers, private universities, NGOs, provincial governments (in federated states) and others. These entities can voluntarily include materials simply by providing them to someone else using the SMTA (assuming they have the right to do so subject to other potentially applicable national laws) and/or by depositing them in a genebank or other organization that has the mandate to subsequently make these materials available using the SMTA. In some cases, where countries do not have national ABS measures in place (for example, they are not implementing the Nagoya Protocol to the Convention on Biological Diversity) that could also apply to such materials, it may be necessary for the party voluntarily providing the materials to obtain permission from the national competent authority to be able to provide the germplasm.

- PGRFA included in the Multilateral System by international institutions subject to an agreement under Article 15 of the Plant Treaty. To date, 18 international organizations have signed such agreements, including the 11 CGIAR Centers that host international collections and other institutes, such as the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE), International Center for Biosaline Agriculture (ICBA), International Cocoa Genebank and International Coconut Genebank for the South Pacific [6].

2. Materials and Methods

- Notification letters: The Treaty Governing Body Secretariat developed a sample notification letter to be used by Contracting Parties and natural or legal persons (but not international organization that signed Article 15 agreements) to declare available collections they hold under the Plant Treaty framework. This sample notification letter is available in four languages (Arabic, English, French and Spanish) on the Treaty’s website [6] and includes the following fields: name of the Contracting Party/natural or legal person; name of the collection center; location; name of species; and URL address, with additional information about the collection, including, presumably, accession-level information [5]. Eight of the nine Governing Body sessions have adopted resolutions inviting Contracting Parties and natural or legal persons to share such information. The Secretariat posts these notifications on the Plant Treaty webpage entitled “Material available in the Multilateral System” [5], which is updated when it receives new notifications letters. The Secretariat also posts a summary of relevant information, which is drawn from those notification letters, including the name of the country concerned and the total number of accessions under the MLS. This webpage also includes links to the text of Article 15 agreements signed by international organizations. These agreements do not include information about the content of the collections concerned.

- EURISCO: In 2003, the European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources (ECPGR) [9] launched EURISCO to share accession-level information (passport and phenotypic data) about plant genetic resources conserved in ex situ collections maintained in ECPGR member or associate member countries. A total of 2,056,337 accessions (as of 30 November 2021) of crop plants and their wild relatives preserved by 401 institutes in 43 countries are listed in EURISCO [10]. ECPGR member countries, under ECPGR guidance, have recommended the policy to make non-Annex I materials available under the same terms and conditions as Annex I materials. Thus, EURISCO enables the specification for each accession whether it is included in the Multilateral System or is available under the SMTA (if non-Annex I), while the holding institutes retain full ownership and control over their PGRFA collections and associated data [10]. EURISCO is one of the data providers to Genesys and WIEWS [11,12].

- Genesys: In 2008, Bioversity International (now, the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT), on behalf of the System-wide Genetic Resources Programme of the CGIAR, the Global Crop Diversity Trust (GCDT), and the Secretariat of the Plant Treaty, launched Genesys as a collaborative project [11,13] to collate and share PGRFA accession-level information from sources worldwide, including Article 15 collections hosted by international organizations, national collections, and others. Since 2012, Genesys has been managed by the GCDT. Passport, characterization and evaluation data and images of 4,137,788 germplasm accessions are available through Genesys as of 30 November 2021 [11]. Networks, institutions and international, national and regional genebanks can contribute data to Genesys by signing a data provider’s agreement, while retaining full ownership and control over the data of their PGRFA collections. The GCDT is recognized as an essential element of the funding strategy of the Plant Treaty. Genesys includes data from over 500 collections around the world (including all the CGIAR Centers and the data from EURISCO) [11]. It does not include information about PGRFA in in situ or on-farm conditions.

- WIEWS: This database was originally launched in 1993, eight years before the Plant Treaty text was adopted [14], to facilitate information exchange and to periodically assess the state of conservation and use of the world’s PGRFA. In 2015, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (CGRFA) decided to integrate an information field into WIEWS [15,16] about whether or not accessions listed in WIEWS are included in the Multilateral System. The accession-level information available in WIEWS is limited to passport data; it does not include any PGRFA characterization and evaluation data and is thus less detailed than the accession-level information in Genesys. It does not include any information about PGRFA in in situ or on-farm conditions. As of August 2021, the WIEWS database contained information on 5,700,826 accessions, provided and updated by 114 member countries and 17 international/regional centers [13]. Through the WIEWS Reporting Tool, countries report to the FAO on the implementation of the Second Global Plan of Action for PGRFA (GPA II) every 3–5 years, and on a yearly basis, on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicator 2.5.1a Number of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture secured in either medium- or long-term conservation facilities. Countries report accession-level information, with optional information about their designation under the MLS [13].

- GLIS: In 2017, as anticipated in Article 17 of the Plant Treaty (titled the “Global Information system on PGRFA”) [1], the Plant Treaty Secretariat launched GLIS [17]. The objective of the GLIS is to “facilitate the exchange of information, based on existing information systems, on scientific, technical and environmental matters related to plant genetic resources for food and agriculture”. Through the minting and use of GLIS digital object identifiers (GLIS-DOIs), it is possible to link accession-level information from multiple online information sources, including but not limited to Genesys, WIEWS and EURISCO [13,17]. To be included in or recognized by the GLIS, collection holders/managers must register each accession with a digital object identifier (DOI) through the DOI module [17]. The GLIS Scientific Advisory Committee and the Governing Body endorsed this option to better identify PGRFA and to improve how material can be referenced in third-party systems and in the scientific literature, with the expectation that setting such an international standard will facilitate data interoperability among different systems [13,17,18]. The DOI assignation is not limited to the genebank holdings, as it extends to any object, whether physical, digital, or abstract [19]. The GLIS portal DOI Registration module was launched in October 2017 [20]. The Governing Body welcomed this progress at its Seventh Session and requested that the Secretariat facilitate the assignment of DOIs on a voluntary basis through Resolution 5/2017 [21]. The use of DOIs remains voluntary. As of 30 November 2021, 1,187,393 DOIs had been recorded. DOIs can also be assigned to accessions that are not included in the MLS. At its Sixth Session, the Treaty Governing Body adopted Resolution 3/2015 containing a Program of Work for GLIS (PoW-GLIS) and its further development [22]. During its Ninth Session, the Governing Body reiterated the usefulness of the voluntary application of DOIs and the link between scientific publications and PGRFA data sets was encouraged. Furthermore, Contracting Parties, other governments and stakeholders have been invited to provide resources for the implementation of the PoW-GLIS, in particular to enhance the GLIS portal, review crop ontologies and support capacity development and technology transfer in developing countries in the next six years (2023–2028) [23]. EURISCO, Genesys and WIEWS include the GLIS-DOIs for accessions when they are included in the data submitted by the organizations hosting the materials [10,11,12].

3. Results of a Comparative Analysis of Five Data Information Sources about the Germplasm Available under the Plant Treaty Framework

3.1. The Notification Letters on the Plant Treaty Website

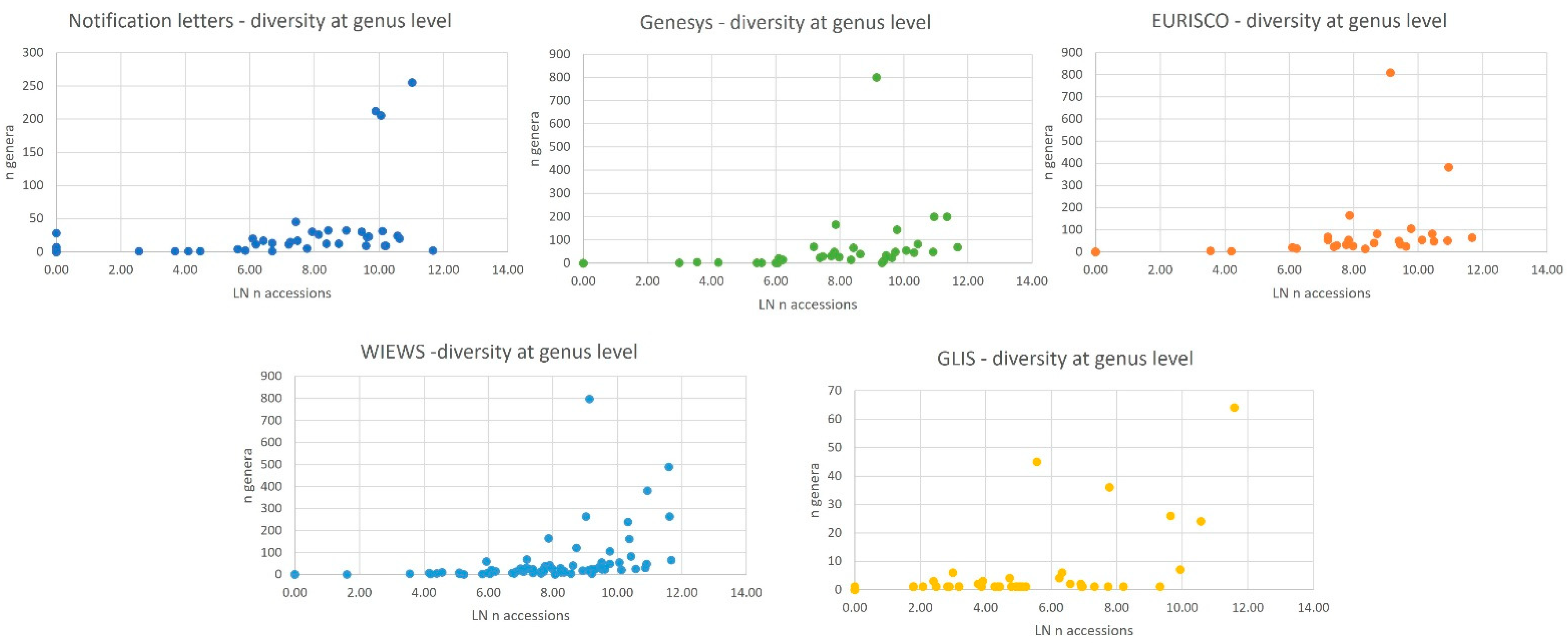

3.2. Comparison across the Five Data Sources regarding PGRFA from Plant Treaty Contracting Parties

3.3. Comparison across Five Data Sources regarding PGRFA from Natural or Legal Persons

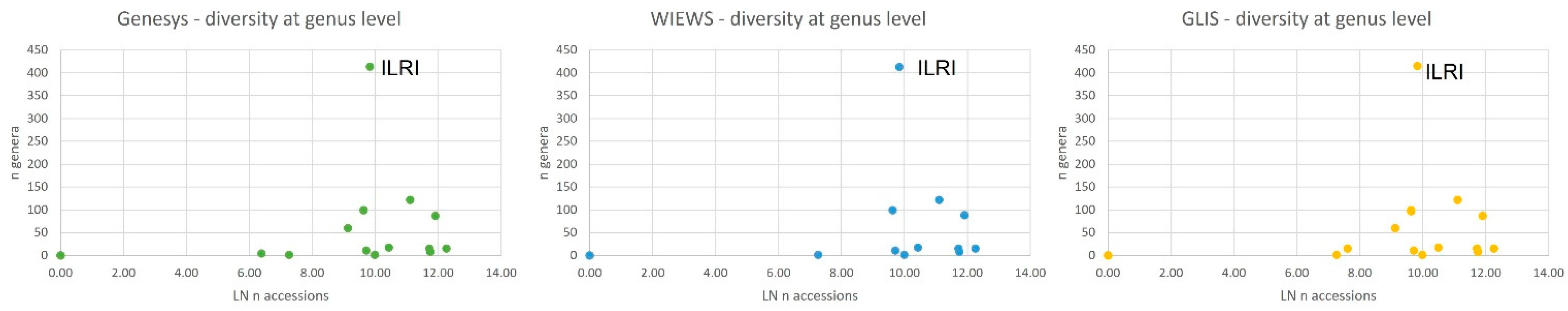

3.4. Comparison across Genesys, WIEWS and GLIS regarding PGRFA from Article 15 Organizations

4. Discussion

4.1. PGRFA Available under the Plant Treaty Framework

4.2. Technical Constraints Encountered When Analyzing Notification Letters and Online Databases

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. 2009. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i0510e.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- FAO. Annex I List of Crops Covered under the Multilateral System. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/bc084e/bc084e.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The Benefit-Sharing Fund. Available online: https://www.fao.org/plant-treaty/areas-of-work/benefit-sharing-fund/bsf-makingprocess/en/ (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Standard Material Transfer Agreement. 2006. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/bc083e/bc083e.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. MLS Data Store. Available online: https://mls.planttreaty.org/itt/index.php?r=stats/pubStats (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture—Material Available in the Multilateral System. Available online: http://www.fao.org/plant-treaty/areas-of-work/the-multilateral-system/collections/en/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. IT/GB-2/07/Report—Second Session of the Governing Body of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. 2007. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/be160e/be160e.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. RESOLUTION 2/2022—Implementation and Operations of the Multilateral System of Access and Benefit-Sharing. p. 4. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/nk237en/nk237en.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- The European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources (ECPGR). Available online: https://www.ecpgr.cgiar.org/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- EURISCO. Available online: http://eurisco.ecpgr.org (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Genesys PGR. Available online: https://www.genesys-pgr.org/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- WIEWS—World Information and Early Warning System on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Available online: https://www.fao.org/wiews/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- CGRFA. Strengthening Cooperation among Global Information Systems on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb6692en/cb6692en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- CGRFA. Report of the Commission on Plant Genetic Resources—Fifth Session, Rome, 19–23 April 1993 (CPGR/93/REP). 1993. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/aj632e/aj632e.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- CGRFA. CGRFA-15/15/Report—Fifteenth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture—Rome, 19–23 January 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/mm660e/mm660e.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- CGRFA. Reporting Format for Monitoring the Implementation of the Second Global Plan of Action for Plant and Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (Item 2.2 of the Fifteenth Regular Session—Rome, 19–23 January 2015) Provisional Agenda of 2015. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/mm294e/mm294e.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Global Information System (GLIS). Available online: https://glis.fao.org/glis/ (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- CGIAR Genebank Platform. CGIAR Centers’ Use of Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs): A Submission to the Advisory Committee on the Global Information System. 2019. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/102457/CGIAR%20report%20regarding%20use%20of%20DOIs.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- DOI Foundation. Available online: https://www.doi.org (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Alercia, A.; López, F.M.; Hamilton, N.R.S.; Marsella, M. Digital Object Identifiers for Food Crops—Descriptors and Guidelines of the Global Information System; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. RESOLUTION 5/2017—Implementation of the Global Information System. 2017. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/mv103e/mv103e.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. RESOLUTION 3/2015—The Vision and the Programme of Work on the Global Information System. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/bl140e/bl140e.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. RESOLUTION 5/2022—Implementation of the Global Information System. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/nk240en/nk240en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Alercia, A.; Diulgheroff, S.; Mackay, M. FAO/Bioversity Multi-Crop Passport Descriptors V.2.1 [MCPD V.2.1]; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2015; p. 12. Available online: https://www.bioversityinternational.org/e-library/publications/detail/descripteurs-de-passeport-multi-cultures-faobioversity-v21/ (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- WIEWS Glossary. Available online: http://www.fao.org/wiews/glossary/en/ (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Taxonomic Information on Cultivated Plants in GRIN-Global. Available online: https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxon/abouttaxonomy (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Mansfeld’s World Database of Agriculture and Horticultural Crops. Available online: https://mansfeld.ipk-gatersleben.de/ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- KEW. Plants of the World Online. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Taxonomic Standardization of Plant Species Names (Taxonstand). Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=Taxonstand (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- The Plant List. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture—List of Contracting Parties. Available online: http://www.fao.org/plant-treaty/countries/membership/en/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- CGRFA. Eighteenth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture—27 September–1 October 2021 (CGRFA-18/21/Report). 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/nh331en/nh331en.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

| Contracting Party | Number of Notifications | Contracting Party | Number of Notifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | 1 | Madagascar | 1 |

| Australia | 1 | Malawi | 1 |

| Austria | 1 | Morocco | 1 |

| Belgium | 5 | Namibia | 1 |

| Bhutan | 1 | Nepal | 1 |

| Brazil | 1 | Netherlands | 1 |

| Burkina Faso | 1 | Philippine | 1 |

| Canada | 1 | Poland | 2 |

| Costa Rica | 1 | Portugal | 1 |

| Croatia | 1 | Romania | 1 |

| Cyprus | 1 | Rwanda | 1 |

| Czech Republic | 1 | Senegal | 1 |

| Egypt | 1 | Spain | 2 |

| Estonia | 1 | Sudan | 1 |

| France | 2 | Sweden | 1 |

| Germany | 1 | Switzerland | 1 |

| India | 1 | Tanzania | 1 |

| Italy | 2 | Uganda | 1 |

| Japan | 3 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| Jordan | 1 | Uruguay | 1 |

| Kenya | 1 | United States of America | 1 |

| Lebanon | 2 | Zambia | 1 |

| Natural or Legal Person | Number of Notifications | Natural or Legal Person | Number of Notifications |

| Association of Communities in the Potato Park | 1 | Costa Rica—Universidad de Costa Rica | 1 |

| India—Peermade Development Society | 1 | France—Association Française des Semences de céréales à paille et autres espèces Autogames (AFSA); the National Institute for Agricultural Research of France (INRA) | 1 |

| Kenya—Maseno University | 1 | France—Association pour l’Etude et l’Amélioration du Maïs (Pro-Maïs); the National Institute for Agricultural Research of France (INRA) | 1 |

| Notification Letters | Genesys | EURISCO | WIEWS | GLIS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secretariat’s Summary | Text of the Letter or URL | ||||||||||

| Country | No. Accessions | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera |

| Afghanistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 953 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Albania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2286 | 31 | 2343 | 32 | 2299 | 31 | 0 | 0 |

| Armenia | 1640 | NA | NA | 2504 | 48 | 2545 | 53 | 1088 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Australia | NA | >20,000 | 212 | 84,476 | >200 | 0 | 0 | 109,526 | ≈489 | 0 | 0 |

| Austria | 5487 | NA | NA | 5607 | 40 | 5607 | 40 | 5607 | 40 | 18 | 1 |

| Azerbaijan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8386 | 263 | 0 | 0 |

| Bangladesh | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9917 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| Belarus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Belgium | >149 | 1773 | >17 | 9318 | >800 | 9318 | >809 | 9309 | ≈797 | 138 | 1 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Bhutan | 60 | 60 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brazil | 2377 | 2377 | 5 | 11,121 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3184 | 1 | 11,216 | 1 |

| Bulgaria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 2 | 67 | 2 | 67 | 2 | 43 | 2 |

| Burkina Faso | 16,479 | >16,179 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Burundi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 188 | 1 |

| Canada | 100,500 | 23,473 | >205 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 111,156 | 264 | 0 | 0 |

| Chile | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Costa Rica | NA | Not found | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 164 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Croatia | 387 | 442 | 20 | 442 | 20 | 442 | 20 | 442 | 20 | 12 | 1 |

| Cyprus | 485 | 485 | 11 | 504 | 15 | 504 | 15 | 504 | 15 | 6 | 1 |

| Czech Republic | 32,616 | 14,863 | 9 | 56,178 | >200 | 56,716 | 381 | 56,314 | 381 | 12 | 1 |

| Denmark | 0 | 0 | 0 | 431 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 423 | 4 | 24 | 1 |

| Ecuador | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13,546 | 55 | 50 | 3 |

| Egypt | 40 | 40 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10,998 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Eritrea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1205 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Estonia | 2496 | 3407 | 26 | 2897 | 26 | 2897 | 26 | 2897 | 26 | 24 | 1 |

| Ethiopia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 52,657 | 29 | 0 | 0 |

| Finland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 400 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 120 | 1 |

| France | 1341 | 1349 | 11 | 4235 | 14 | 4235 | 14 | 4235 | 14 | 1020 | 1 |

| Germany | 108,675 | 117,110 | >2 | 117,404 | 68 | 117,257 | 64 | 117,256 | 66 | 108,203 | 64 |

| Ghana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 163 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

| Greece | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 24 | 1 |

| Guinea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 96 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Guyana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 81 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Honduras | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Hungary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2617 | 165 | 2617 | 164 | 2617 | 165 | 168 | 1 |

| India | 26,523 | 26,523 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1513 | 1 |

| Indonesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 332 | 2 | 1058 | 1 |

| Italy | 46,788 | 46,788 | Not found | 16,821 | 48 | 12,075 | 49 | 17,482 | 48 | 20,720 | 7 |

| Japan | 40,000 | 38,960 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38,959 | 25 | 38,959 | 24 |

| Jordan | 1885 | >1885 | Not found | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2335 | 37 | 2389 | 36 |

| Kenya | 12,873 | 12,873 | 30 | 225 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 25,054 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1382 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Latvia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1751 | 29 | 1751 | 29 | 1308 | 29 | 0 | 0 |

| Lebanon | 274 | 1676 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 380 | ≈59 | 261 | 45 |

| Madagascar | 7999 | >7999 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7563 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Malawi | 1419 | 1419 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2702 | ≈42 | 20 | 6 |

| Malaysia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9998 | 4 | 721 | 2 |

| Mali | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2078 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Mongolia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1197 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Montenegro | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 4 | 35 | 4 | 35 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Morocco | NA | >352 | >2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Namibia | 1441 | Not found | Not found | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nepal | 614 | 614 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The Netherlands | 15,218 | >15,226 | >22 | 15,029 | 23 | 15,179 | 25 | 15,042 | 23 | 15,440 | 26 |

| Niger | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3876 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Norway | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2059 | 13 | 24 | 1 |

| Pakistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30,643 | ≈239 | 0 | 0 |

| Panama | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 391 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Papua New Guinea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1615 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Peru | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5258 | 4 | 17 | 1 |

| The Philippines | 811 | 811 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4271 | 9 | 3675 | 1 |

| Poland | 61,627 | 61,627 | 255 | 54,649 | 48 | 55,089 | 50 | 54,619 | 48 | 519 | 4 |

| Portugal | 813 | 813 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31,884 | 161 | 2292 | 1 |

| Qatar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Republic of Ireland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1601 | 23 | 1601 | 23 | 1601 | 23 | 24 | 1 |

| Republic of Lithuania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1326 | 70 | 1326 | 68 | 1326 | 68 | 0 | 0 |

| Romania | 6363 | 2790 | 30 | 4531 | 66 | 6180 | 82 | 6251 | 121 | 150 | 1 |

| Russian Federation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Rwanda | NA | Not found | >28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Senegal | 49 | Not found | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 898 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Serbia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 114 | 4 |

| Slovakia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12,629 | 34 | 12,629 | 34 | 12,629 | 34 | 0 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1332 | 54 | 1332 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 1 |

| Spain | 41,521 | 41,521 | >20 | 23,503 | 54 | 24,877 | 54 | 23,517 | 54 | 1000 | 2 |

| Sudan | 6351 | 6351 | 12 | 11,816 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 9002 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Sweden | 24,713 | 24,713 | 31 | 30,292 | 45 | 35,934 | 48 | 30,523 | NA | 84 | 1 |

| Switzerland | 25,507 | 25,507 | Not found | 33,965 | 82 | 33,965 | 82 | 33,868 | 82 | 72 | 1 |

| Tajikistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3782 | 28 | 0 | 0 |

| The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Togo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 845 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Tunisia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13,780 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Turkey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 156 | 1 |

| Uganda | 760 | 87 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2236 | 12 | 566 | 6 |

| United Kingdom | 42,722 | >27,390 | 9 | 17,746 | 144 | 17,655 | 105 | 17,485 | 105 | 138 | 1 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | NA | 277 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| United States of America | NA | 4600 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Uruguay | 13 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Uzbekistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 189 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Zambia | 4340 | >4340 | >12 | 261 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4246 | 15 | 11 | 3 |

| TOT Accessions | >643,356 | >556,713 | 528,019 | 424,176 | 947,800 | 211,282 | |||||

| Notification Letters | Genesys | WIEWS | GLIS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secretariat’s Summary | Text of the Letter or URL | |||||||||

| # | Country | No. Accessions | Country | No. Accessions | Country | No. Accessions | Country | No. Accessions | Country | No. Accessions |

| 1. | Germany | 108,675 | Germany | 117,110 | Germany | 117,404 | Germany | 117,256 | Germany | 108,203 |

| 2. | Canada | 100,500 | Poland | 61,627 | Australia | 84,476 | Canada | 111,156 | Japan | 38,959 |

| 3. | Poland | 61,627 | Italy | 46,788 | Czech Republic | 56,178 | Australia | 109,526 | Italy | 20,720 |

| Natural or Legal Person | Notification Letters | Genesys | EURISCO | WIEWS | GLIS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secretariat’s Summary | Text of the Letter or URL | ||||||||||

| No. Accessions | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | |

| Assoc. of Comm. Potato Park | NA | Not found | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| India—Peermade Development Society | 7 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kenya—Maseno University | 12 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Costa Rica—Universidad de Costa Rica | NA | 128 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| France—AFSA and INRA | 1784 | 1784 | 1 | 2983 | 4 | 2983 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| France—Pro-Maïs INRA | 533 | 533 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TOT Accessions | >2336 | >2464 | 2983 | 2983 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| International Institute | Genesys | WIEWS | GLIS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | No. Accessions | No. Genera | |

| Africa Rice | 21,812 | 1 | 21,812 | 1 | 21,812 | 1 |

| Bioversity International | 1424 | 1 | 1424 | 1 | 1424 | 1 |

| CIAT | 66,599 | 122 | 66,599 | 122 | 66,749 | 122 |

| CIMMYT | 210,851 | 15 | 210,851 | 15 | 211,315 | 15 |

| CIP | 16,477 | 11 | 16,477 | 11 | 16,578 | 11 |

| ICARDA | 148,419 | ≈87 | 148,419 | 88 | 147,135 | 87 |

| ICRAF | 15,157 | 99 | 15,157 | 99 | 15,156 | 99 |

| ICRISAT | 123,425 | 15 | 123,051 | 15 | 122,870 | 15 |

| IITA | 33,758 | 17 | 33,758 | 17 | 36,156 | 17 |

| ILRI | 18,638 | ≈414 | 18,638 | 413 | 18,636 | 415 |

| IRRI | 127,240 | 8 | 127,241 | 8 | 127,240 | 8 |

| Centre for Pacific Crops and Trees (CePaCT)—Pacific Community—(SPC) | 592 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2025 | 15 |

| International Center for Biosaline Agriculture (ICBA) | 15,141 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 15,141 | 97 |

| International Cocoa Genebank | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International Coconut Genebank for African and the Indian Ocean | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International Coconut Genebank for the South Pacific | Not found | Not found | Not found | Not found | Not found | Not found |

| Mutant Germplasm Repository of the FAO/IAEA Joint Division | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE) | 9275 | 60 | 9297 | 61 | 9190 | 60 |

| TOT Accessions | 808,808 | 792,724 | 811,427 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gullotta, G.; Engels, J.M.M.; Halewood, M. What Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Are Available under the Plant Treaty and Where Is This Information? Plants 2023, 12, 3944. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12233944

Gullotta G, Engels JMM, Halewood M. What Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Are Available under the Plant Treaty and Where Is This Information? Plants. 2023; 12(23):3944. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12233944

Chicago/Turabian StyleGullotta, Gaia, Johannes M. M. Engels, and Michael Halewood. 2023. "What Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Are Available under the Plant Treaty and Where Is This Information?" Plants 12, no. 23: 3944. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12233944

APA StyleGullotta, G., Engels, J. M. M., & Halewood, M. (2023). What Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Are Available under the Plant Treaty and Where Is This Information? Plants, 12(23), 3944. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12233944