Current Trends for Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Crops and Products with Emphasis on Essential Oil Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

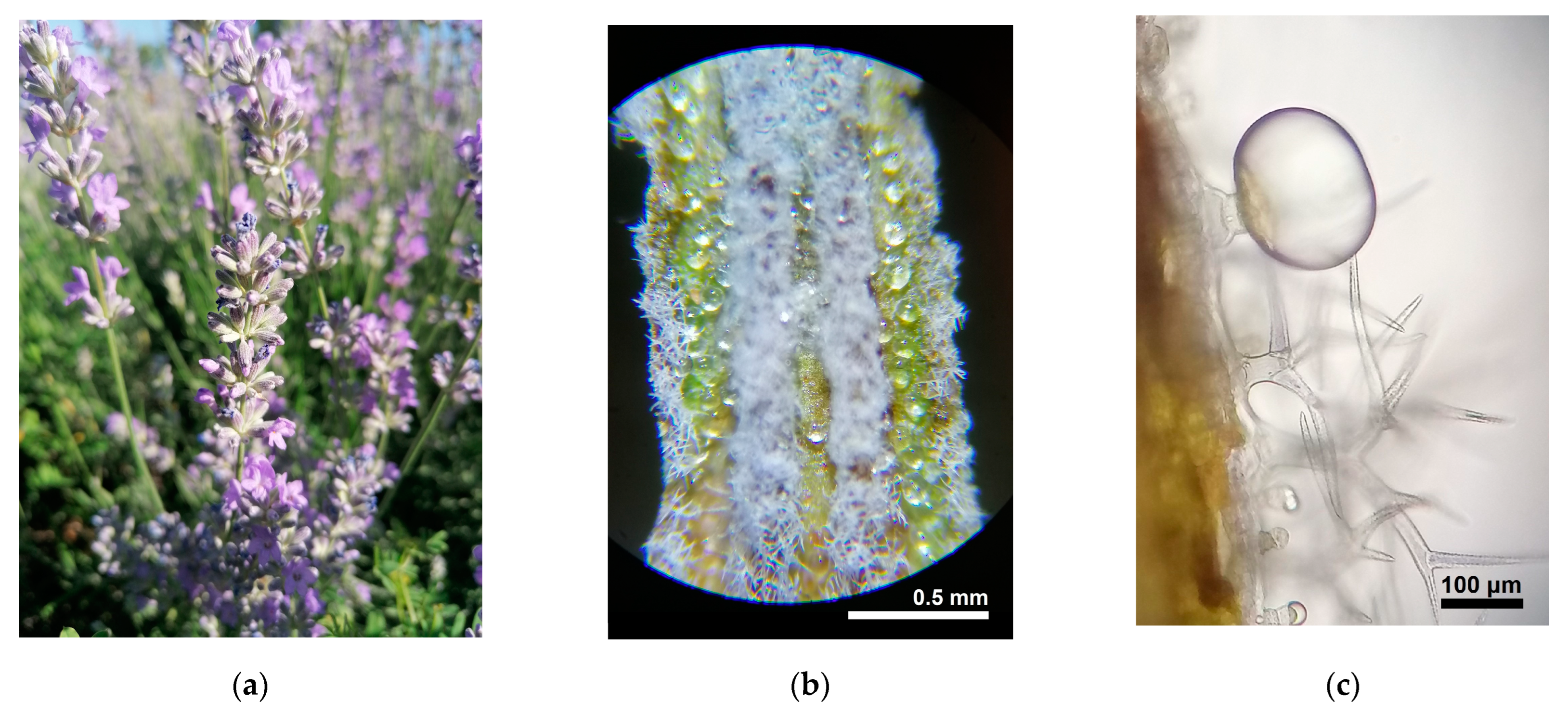

2. Origin, Botany and Phytochemistry of the Genus Lavandula

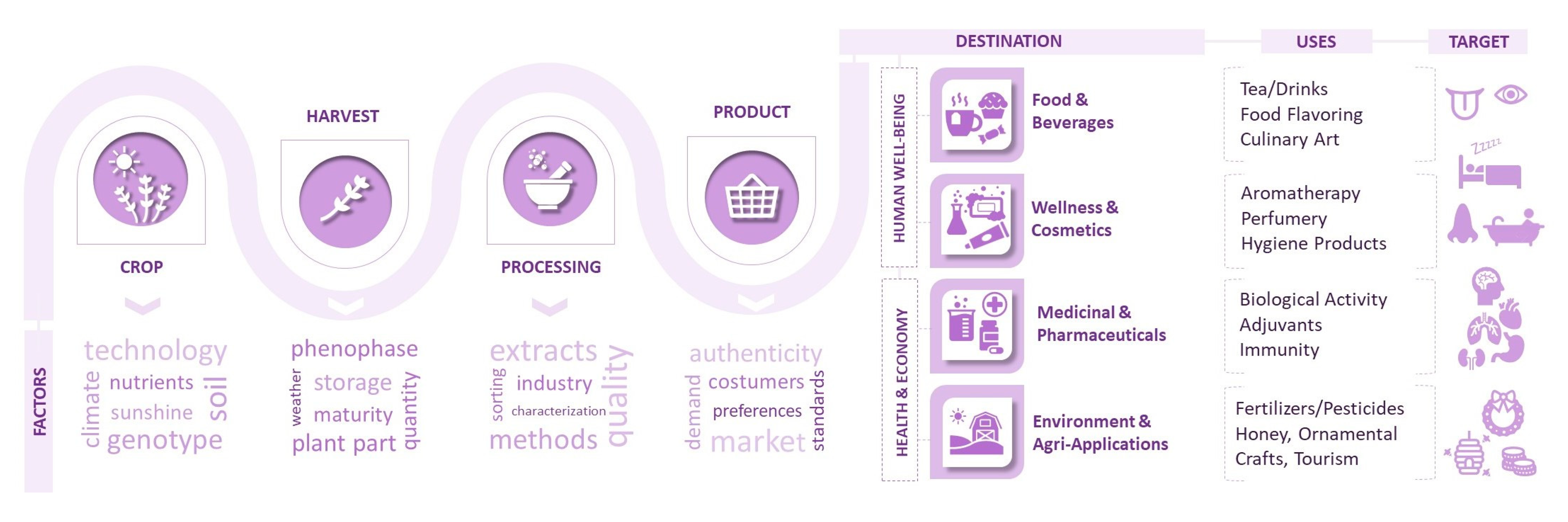

3. Cultivation Challenges and Trends for L. angustifolia Crop

3.1. Cultivated Plant Habit

3.2. Requirements for Environmental Factors

3.3. Crop Establishment and Propagation

3.3.1. Propagation

3.3.2. Field Crops

3.3.3. Potted Plants and Unconventional Crops

3.4. Crop Care

3.4.1. Weed Control a Challenge for Lavender Crops

3.4.2. Pests and Diseases of Lavender Crops

3.4.3. The Key to Pruning Lavender

3.4.4. Fertilization

3.5. Harvest, Drying and Yield

3.6. Extraction

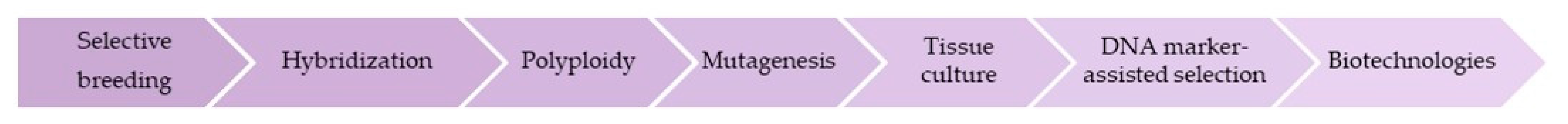

4. Genotypes Cultivated and Breeding Trends

5. Overview on the Importance and Emerging Uses of L. angustifolia

5.1. Food and Beverages

5.2. Wellness and Cosmetics

5.3. Medicinal Uses and Pharmaceutical Potential

5.4. Environment, Agri-Applications and Niche Uses

6. Essential Oil Standards for L. angustifolia

6.1. Sensorial Quality of Essential Oil

6.2. Current Standards and Trending Guidelines for Essential Oil Quality

- good agricultural practices (GAP)

- origin certification schemes that guarantee specific origin/quality/attributes

- organic product schemes

- multi-purpose schemes that can combine GAP and quality management

- traceability and safety schemes

- other schemes: non-GMO, Fairtrade [138].

6.3. Safety and Authenticity Issues

7. Summary of the Factors Influencing Essential Oil of L. angustifolia

7.1. Factors Related to Plant Biology, Cultivation and Harvesting

7.2. Factors Related to Drying, Extraction and Storage

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lubbe, A.; Verpoorte, R. Cultivation of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants for Specialty Industrial Materials. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 34, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Borsotto, P. Essential Oils: Market and Legislation; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78923-780-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gallotte, P.; Fremondière, G.; Gallois, P.; Bernier, J.-P.B.; Buchwalder, A.; Walton, A.; Piasentin, J.; Fopa-Fomeju, B. Lavandula angustifolia Mill. and Lavandula x Intermedia Emeric Ex Loisel: Lavender and Lavandin. In Medicinal, Aromatic and Stimulant Plants; Novak, J., Blüthner, W.-D., Eds.; Handbook of Plant Breeding; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 303–311. ISBN 978-3-030-38792-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, R.; Truong, F.; Adal, A.M.; Sarker, L.S.; Mahmoud, S.S. Lavandula Essential Oils: A Current Review of Applications in Medicinal, Food, and Cosmetic Industries of Lavender. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1934578X1801301038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, L.S.; Tămaș, M.; Muntean, S.; Muntean, L.; Duda, M.M.; Vârban, D.I.; Florian, S. Treatise of Cultivated and Spontaneous Medicinal Plants; Risoprint: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2016; ISBN 978-973-53-1873-4. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, K.V. Handbook of Herbs and Spices: Volume 2; Woodhead Publishing: Abington Cambridge, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1-85573-721-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lis-Balchin, M. Lavender: The Genus Lavandula; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 0-203-21652-0. [Google Scholar]

- Giray, F.H. An Analysis of World Lavender Oil Markets and Lessons for Turkey. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 1612–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijulie, I.; Lequeux-Dincă, A.-I.; Preda, M.; Mareci, A.; Matei, E. Could Lavender Farming Go from a Niche Crop to a Suitable Solution for Romanian Small Farms? Land 2022, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, C.; Stintzing, F.C. Stability of Essential Oils: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadar, R.-L.; Amuza, A.; Dumitras, D.E.; Mihai, M.; Pocol, C.B. Analysing Clusters of Consumers Who Use Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Leon, A.; Moreno-Pérez, G.F.; Martínez-Gordillo, M.; Aguirre-Hernández, E.; Valle-Dorado, M.G.; Díaz-Reval, M.I.; González-Trujano, M.E.; Pellicer, F. Lamiaceae in Mexican Species, a Great but Scarcely Explored Source of Secondary Metabolites with Potential Pharmacological Effects in Pain Relief. Molecules 2021, 26, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.G. Plant Systematics; Elsevier Academic Press: Burlington, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 0-12-644460-9. [Google Scholar]

- Uritu, C.M.; Mihai, C.T.; Stanciu, G.-D.; Dodi, G.; Alexa-Stratulat, T.; Luca, A.; Leon-Constantin, M.-M.; Stefanescu, R.; Bild, V.; Melnic, S.; et al. Medicinal Plants of the Family Lamiaceae in Pain Therapy: A Review. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2018, 7801543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vârban, R.; Vidican, R.; Ona, A.D.; Vârban, D.; Stoie, A.; Gâdea, Ș.; Vâtcă, S.; Stoian, V.; Crișan, I.; Stoian, V. Modelling Plant Morphometric Parameters as Predictors for Successful Cultivation of Some Medicinal Agastache Species. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2022, 50, 12638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrato-Valenti, G.; Bisio, A.; Cornara, L.; Ciarallo, G. Structural and Histochemical Investigation of the Glandular Trichomes of Salvia Aurea L. Leaves, and Chemical Analysis of the Essential Oil. Ann. Bot. 1997, 79, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Ding, P. Production of Essential Oil in Plants: Ontogeny, Secretory Structures and Seasonal Variations. Pertanika J. Sch. Res. Rev. 2016, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Maurya, S.; Chandra, M.; Yadav, R.K.; Narnoliya, L.K.; Sangwan, R.S.; Bansal, S.; Sandhu, P.; Singh, U.; Kumar, D.; Sangwan, N.S. Interspecies Comparative Features of Trichomes in Ocimum Reveal Insights for Biosynthesis of Specialized Essential Oil Metabolites. Protoplasma 2019, 256, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, N.G.; Tundis, R.; Upson, T.M. A New Species of Lavandula Sect. Lavandula (Lamiaceae) and Review of Species Boundaries in Lavandula angustifolia. Phytotaxa 2017, 292, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Mnayer, D.; Özçelik, B.; Altin, G.; Kasapoğlu, K.N.; Daskaya-Dikmen, C.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Selamoglu, Z.; Acharya, K.; Sen, S.; et al. Plants of the Genus Lavandula: From Farm to Pharmacy. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1385–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, H.M.A.; Wilkinson, J.M. Biological Activities of Lavender Essential Oil. Phytother. Res. 2002, 16, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demasi, S.; Caser, M.; Lonati, M.; Cioni, P.L.; Pistelli, L.; Najar, B.; Scariot, V. Latitude and Altitude Influence Secondary Metabolite Production in Peripheral Alpine Populations of the Mediterranean Species Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanev, S.; Zagorcheva, T.; Atanassov, I. Lavender Cultivation in Bulgaria—21st Century Developments, Breeding Challenges and Opportunities. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 22, 584–590. [Google Scholar]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Gille, E.; Trifan, A.; Luca, V.S.; Miron, A. Essential Oils of Lavandula Genus: A Systematic Review of Their Chemistry. Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 761–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despinasse, Y.; Moja, S.; Soler, C.; Jullien, F.; Pasquier, B.; Bessière, J.-M.; Baudino, S.; Nicolè, F. Structure of the Chemical and Genetic Diversity of the True Lavender over Its Natural Range. Plants 2020, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassiotis, C.N.; Ntana, F.; Lazari, D.M.; Poulios, S.; Vlachonasios, K.E. Environmental and Developmental Factors Affect Essential Oil Production and Quality of Lavandula angustifolia during Flowering Period. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitton, Y.; Nicolè, F.; Moja, S.; Valot, N.; Legrand, S.; Jullien, F.; Legendre, L. Differential Accumulation of Volatile Terpene and Terpene Synthase MRNAs during Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia and L. x Intermedia) Inflorescence Development. Physiol. Plant 2010, 138, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriti, M.; Colnaghi, G.; Chemat, F.; Smadja, J.; Faoro, F.; Visinoni, F.A. Histo-Cytochemistry and Scanning Electron Microscopy of Lavender Glandular Trichomes Following Conventional and Microwave-Assisted Hydrodistillation of Essential Oils: A Comparative Study. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, A.; Zamfirache, M.M.; Ivănescu, L.C. Histo-Anatomical and Micromorphological Modifications of the Stem and Leaves in Four Cultivars of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Supplemented with Hoagland Nutrient Solution. Tudia Univ. “Vasile Goldiş” Ser. Ştiinţ. Vieţi 2021, 31, 150–163. [Google Scholar]

- Raunkiaer, C. Plant Life Forms. Available online: https://www.gali-izard.arch.ethz.ch/home/plant-life-forms-c-raunkiaer-1937 (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Colțun, M. Step-by-Step Creation of a Lavender Plantation. J. Bot. 2016, 8, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hailey, L. Is Lavender Considered a Flower, Herb, or Shrub? Available online: https://www.allaboutgardening.com/lavender-flower-herb-shrub/ (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Simonet-Avril, A. Lavender: Lavender in Nature and Garden, Home and Kitchen; KubiK/RvR: Kehl, Germany, 2005; ISBN 978-3-938265-14-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J. Growing and Knowing Lavender; ACS Distance Education: Nerang, QLD, Australia, 2014; ISBN 978-0-9925878-0-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sałata, A.; Buczkowska, H.; Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R. Yield, Essential Oil Content, and Quality Performance of Lavandula angustifolia Leaves, as Affected by Supplementary Irrigation and Drying Methods. Agriculture 2020, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgini Shabankareh, H.; Khorasaninejad, S.; Soltanloo, H.; Shariati, V. Investigation of the Effects of Drought Stress and Abscisic Acid Foliar Application on Yield, Physiological and Biochemical Properties of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Cv. Organic Munstead). J. Crop Prod. 2021, 14, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, E.S. Lavender: How to Grow and Use the Fragrant Herb; Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, PA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-8117-4327-3. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 3515:2002; Oil of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Bader, S.B. The Lavender Lover’s Handbook: The 100 Most Beautiful and Fragrant Varieties for Growing, Crafting, and Cooking; Timber Press: Portland, ON, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-60469-399-7. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaş, İ.; Bahri, İ. Effects of Three Different Rooting Media on Some Rooting Parameters of Cuttings Belonging to Lavandula angustifolia and Lavandula intermedia Species. Acta Nat. Sci. 2021, 2, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirimer, N.; Mokhtarzadeh, S.; Demirci, B.; Goger, F.; Khawar, K.M.; Demirci, F. Phytochemical Profiling of Volatile Components of Lavandula angustifolia Miller Propagated under in vitro Conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 96, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabin, R.; Saraswoti, K.; Sabari, R. In-Vitro Propagation of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). J. Pl. Res. 2018, 16, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Najar, B.; Demasi, S.; Caser, M.; Gaino, W.; Cioni, P.L.; Pistelli, L.; Scariot, V. Cultivation Substrate Composition Influences Morphology, Volatilome and Essential Oil of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Agronomy 2019, 9, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fascella, G.; Mammano, M.M.; D’Angiolillo, F.; Pannico, A.; Rouphael, Y. Coniferous Wood Biochar as Substrate Component of Two Containerized Lavender Species: Effects on Morpho-Physiological Traits and Nutrients Partitioning. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 267, 109356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgiu, R.M.; Morar, G.; Dumitraș, A.; Vlăsceanu, G.; Dune, A.; Schroeder, F.-G. A Study of the Cultivation of Medicinal Plants in Hydroponic and Aeroponic Technologies in a Protected Environment. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1170, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Panayiotou, C.; Tzortzakis, N. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Levels Affected Plant Growth, Essential Oil Composition and Antioxidant Status of Lavender Plant (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 83, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Drouza, C.; Tzortzakis, N. Optimization of Potassium Fertilization/Nutrition for Growth, Physiological Development, Essential Oil Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2017, 17, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vârban, R.; Vârban, D.I.; Stoie, A.; Bogdan, I.; Odagiu, A.; Ghețe, A. Identification of Weed Species Present in Lavender Crops (Lavandula angustifolia L.) and (Mentha Piperita L.) from the UASVM Cluj-Napoca Campus. Hop. Med. Plants 2018, 26, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Vouzounis, N.A.; Dararas, V.E.; Georghiou, G. Chemical Control of Weeds in the Aromatic Crops Lavender, Oregano and Sage. Tech. Bull. 2003, 218, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, R.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Abd Allah, E.F. Bioherbicides: Current Knowledge on Weed Control Mechanism. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 158, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Ahmad-Hamdani, M.S.; Rosli, A.M.; Hamdan, H. Bioherbicides: An Eco-Friendly Tool for Sustainable Weed Management. Plants 2021, 10, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, K. Monitoring of Fungal Diseases of Lavender. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Radev, Z. Study of the representatives of pests in Lavender (Lavandula). New Knowl. J. Sci. 2020, 9, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.J.; Parkinson, N.M. A Bacterial Leaf Spot and Shoot Blight of Lavender Caused by Xanthomonas Hortorum in the UK. New Dis. Rep. 2014, 30, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuche, J.; Danet, J.-L.; Rivoal, J.-B.; Arricau-Bouvery, N.; Thiéry, D. Minor Cultures as Hosts for Vectors of Extensive Crop Diseases: Does Salvia Sclarea Act as a Pathogen and Vector Reservoir for Lavender Decline? J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, Z. Study of Sudden Decline of Lavender in Bulgaria Caused by ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma Solani’. Bulg. J. Crop Sci. 2022, 59, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Özalp, T.; Könül, G.; Ayyıldız, Ö.; Tülek, A.; Devran, Z. First report of root-knot nematode Meloidogyne arenaria on lavender in Turkey. J. Nematol. 2020, 52, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sémétey, O.; Gaudin, J.; Danet, J.-L.; Salar, P.; Theil, S.; Fontaine, M.; Krausz, M.; Chaisse, E.; Eveillard, S.; Verdin, E.; et al. Lavender Decline in France Is Associated with Chronic Infection by Lavender-Specific Strains of “Candidatus Phytoplasma Solani”. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01507-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.-Y.; Pan, R.; Abid, M.; Zang, H.-Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, Y. First Report of Blackleg Disease Caused by Epicoccum Sorghinum on Lavender (Lavandula Stoechas) in China. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radev, Z. Study on the use of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) for biological control against pests in lavender (Lavandula officinalis L.). New Knowl. J. Sci. 2020, 9, 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E.A.; Dainese, M.; Clough, Y.; Báldi, A.; Bommarco, R.; Gagic, V.; Garratt, M.P.D.; Holzschuh, A.; Kleijn, D.; Kovács-Hostyánszki, A.; et al. The Interplay of Landscape Composition and Configuration: New Pathways to Manage Functional Biodiversity and Agroecosystem Services across Europe. Ecol. Lett. 2019, 22, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use. In Guideline on Good Agricultural and Collection Practice (GACP) for Starting Materials of Herbal Origin; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajan, S.; Sukumaran, S. Chapter 12—Chemistry and Toxicology behind Chemical Fertilizers. In Controlled Release Fertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture; Lewu, F.B., Volova, T., Thomas, S., Rakhimol, K.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 195–229. ISBN 978-0-12-819555-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalașcu, C.; Tudor, V.; Bolohan, C.; Mihalache, M.; Ionuţ, R. The Effect of Different Fertilization upon the Growth and Yield of Some Lavandula angustifolia (Mill.) Varieties Grown in South East Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. B Hortic. 2020, 64, 685–692. [Google Scholar]

- Mavandi, P.; Abbaszadeh, B.; Emami Bistgani, Z.; Barker, A.V.; Hashemi, M. Biomass, Nutrient Concentration and the Essential Oil Composition of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Grown with Organic Fertilizers. J. Plant Nutr. 2021, 44, 3061–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan, I.; Vidican, R.; Stoian, V. Induced Modifications on Secondary Metabolism of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants—An Endomycorrhizal Approach. Hop. Med. Plants 2018, 26, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, G.C.; Popescu, M. Role of Combined Inoculation with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi, as a Sustainable Tool, for Stimulating the Growth, Physiological Processes, and Flowering Performance of Lavender. Sustainability 2022, 14, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkina, N.; Logvinenko, L.; Novitsky, M.; Zamana, S.; Sokolov, S.; Molchanova, A.; Shevchuk, O.; Sekara, A.; Tallarita, A.; Caruso, G. Yield, Essential Oil and Quality Performances of Artemisia Dracunculus, Hyssopus Officinalis and Lavandula angustifolia as Affected by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi under Organic Management. Plants 2020, 9, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binet, M.-N.; Marchal, C.; Lipuma, J.; Geremia, R.A.; Bagarri, O.; Candaele, B.; Fraty, D.; David, B.; Perigon, S.; Barbreau, V.; et al. Plant Health Status Effects on Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Associated with Lavandula angustifolia and Lavandula Intermedia Infected by Phytoplasma in France. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, K.D.; Evangelopoulos, V.; Gougoulias, N.; Wogiatzi, E. Lavender Organic Cultivation Yield and Essential Oil Can Be Improved by Using Bio-Stimulants. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B-Soil Plant Sci. 2020, 70, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vârban, D.; Zăhan, M.; Pop, C.R.; Socaci, S.; Ștefan, R.; Crișan, I.; Bota, L.E.; Miclea, I.; Muscă, A.S.; Deac, A.M.; et al. Physicochemical Characterization and Prospecting Biological Activity of Some Authentic Transylvanian Essential Oils: Lavender, Sage and Basil. Metabolites 2022, 12, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Détár, E.; Zámbori-Németh, É.; Gosztola, B.; Harmath, A.; Ladányi, M.; Pluhár, Z. Ontogenesis and Harvest Time Are Crucial for High Quality Lavender—Role of the Flower Development in Essential Oil Properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 163, 113334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassiotis, C.N.; Lazari, D.; Vlachonasios, K. The Effects of Habitat Type and Diurnal Harvest on Essential Oil Yield and Composition of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2010, 19, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Capetti, F.; Marengo, A.; Cagliero, C.; Liberto, E.; Bicchi, C.; Rubiolo, P.; Sgorbini, B. Adulteration of Essential Oils: A Multitask Issue for Quality Control. Three Case Studies: Lavandula angustifolia Mill., Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck and Melaleuca Alternifolia (Maiden & Betche) Cheel. Molecules 2021, 26, 5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare. European Pharmacopoeia, 10th ed.; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare of the Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2009; Volume 1, ISBN 978-92-871-8912-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.M.; Poulson, A.; Packer, C.; Carlson, R.E.; Buch, R.M. Essential Oil Profile and Yield of Corolla, Calyx, Leaf, and Whole Flowering Top of Cultivated Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (Lamiaceae) from Utah. Molecules 2021, 26, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binello, A.; Orio, L.; Pignata, G.; Nicola, S.; Chemat, F.; Cravotto, G. Effect of Microwaves on the in Situ Hydrodistillation of Four Different Lamiaceae. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2014, 17, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Sultan, P.; Qazi, P.; Rasool, S. Approaches for the Genetic Improvement of Lavender: A Short Review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 736–740. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Li, J.; Huang, L.; Wang, D.; Huang, P.; Nie, J. The Application of Biotechnology in Medicinal Plants Breeding Research in China. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 21, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokajewicz, K.; Białoń, M.; Svydenko, L.; Fedin, R.; Hudz, N. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil of the New Cultivars of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Bred in Ukraine. Molecules 2021, 26, 5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkikh, I.; Baleev, D.; Morozov, A.; Mizina, P.; Sidelnikov, N. Breeding of Medicinal and Essential Oil Crops in VILAR: Achievements and Prospects. Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genet. Sel. 2021, 25, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassiotis, C.N.; Tarantilis, P.A.; Daferera, D.; Polissiou, M.G. Etherio, a New Variety of Lavandula angustifolia with Improved Essential Oil Production and Composition from Natural Selected Genotypes Growing in Greece. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 32, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu, I. Studiul proprietăților funcționale lavandei (lavandula) cultivate în Republica Moldova. In Technical-Scientific Conference of Undergraduate, Master and Phd Students; Tehnica-UTM: Chișinău, Moldova, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 463–466. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oost, E.; Leus, L.; De Rybel, B.; Van Laere, K. Determination of Genetic Distance, Genome Size and Chromosome Numbers to Support Breeding in Ornamental Lavandula Species. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upson, T.; Andrews, S. The Genus Lavandula; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Kew, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1-84246-010-8. [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva, R.; Kirchev, H.; Delibaltova, V.; Chavdarov, P.; Uhr, Z. Investigation of Some Agricultural Performances of Lavender Varieties. Üzüncü Il Üniversitesi J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 31, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dušková, E.; Dušek, K.; Indrák, P.; Smékalová, K. Postharvest Changes in Essential Oil Content and Quality of Lavender Flowers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 79, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonceariuc, M.; Balmuș, Z.; Cotelea, L.; Mașcovițeva, S.; Butnaraș, V. Botnarenco Pantelimon The Drought Resistance of Salvia Sclarea L. and Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Varieties. Hop. Med. Plants 2018, 22, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Walasek-Janusz, M.; Grzegorczyk, A.; Zalewski, D.; Malm, A.; Gajcy, S.; Gruszecki, R. Variation in the Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils from Cultivars of Lavandula angustifolia and L. × Intermedia. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, M.; Vlas, N.; Szekely-Varga, Z.; Jucan, D.; Zaharia, A. The Influence of Distillation Time and the Flowering Phenophase on Quantity and Quality of the Essential Oil of Lavandula angustifolia Cv. ‘Codreanca’. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018, 23, 14146–14152. [Google Scholar]

- Oroian, C.; Odagiu, A.; Racz, C.P.; Oroian, I.; Mureșan, I.C.; Duda, M.; Ilea, M.; Brașovean, I.; Iederan, C.; Marchiș, Z. Composition of Lavandula angustifolia L. Cultivated in Transylvania, Romania. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2019, 47, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, M.; Bungau, S.; Tit, D.M.; Copolovici, L.; Behl, T.; Otrisal, P.; Aleya, L.; Cioca, G.; Berescu, D.; Uivarosan, D.; et al. Variations in the Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil of Lavandula angustifolia Mill., Moldoveanca 4 Romanian Variety. Rev. Chim. 2020, 71, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, M.A.; Bungau, S.; Tit, D.M.; Zaha, D.C.; Nechifor, A.C.; Behl, T.; Chambre, D.; Lupitu, A.I.; Copolovici, L.; Copolovici, D.M. Chemical Profile, Antioxidant Capacity, and Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils Extracted from Three Different Varieties (Moldoveanca 4, Vis Magic 10, and Alba 7) of Lavandula angustifolia. Molecules 2021, 26, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulavin, I.; Brailko, V.; Zhdanova, I. In vitro Rhizogenesis of the Lavandula angustifolia Cultivars. BIO Web Conf. 2020, 24, 00017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelentsov, S.V.; Moshnenko, E.V.; Shuvaeva, T.P.; Gajtotina, I.V.; Kurov, A.A. The number of glandular trichomes on the peduncles of true lavender inflorescences as an additional breeding trait for essential oil. Oil Crops 2021, 4, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokajewicz, K.; Białoń, M.; Svydenko, L.; Hudz, N.; Balwierz, R.; Marciniak, D.; Wieczorek, P.P. Comparative Evaluation of the Essential Oil of the New Ukrainian Lavandula angustifolia and Lavandula x Intermedia Cultivars Grown on the Same Plots. Molecules 2022, 27, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistelli, L.; Najar, B.; Giovanelli, S.; Lorenzini, L.; Tavarini, S.; Angelini, L.G. Agronomic and Phytochemical Evaluation of Lavandin and Lavender Cultivars Cultivated in the Tyrrhenian Area of Tuscany (Italy). Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, F.; Beruto, M.; Mela, L.; Curir, P.; Triglia, G.; Boggia, R.; Zunin, P.; Monroy, F. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Miller, Cultivar Rosa) Solid By-Products Remaining after the Distillation of the Essential Oil. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.-T.; Shi, L.; Liu, J.-Q.; Han, H. A New Lavender Cultivar ‘Jingxun 2’. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2015, 42, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, N.; Baydar, H. Determination of Lavender and Lavandin Cultivars (Lavandula sp.) Containing High Quality Essential Oil in Isparta, Turkey. Turk. J. Field Crops 2013, 18, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Urwin, N. Improvement of Lavender Varieties by Manipulation of Chromosome Number; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2009; ISBN 1440-6845.

- Malli, R.P.N.; Adal, A.M.; Sarker, L.S.; Liang, P.; Mahmoud, S.S. De Novo Sequencing of the Lavandula angustifolia Genome Reveals Highly Duplicated and Optimized Features for Essential Oil Production. Planta 2019, 249, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Fang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, M. Advances and Challenges in Medicinal Plant Breeding. Plant Sci. 2020, 298, 110573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagorcheva, T.; Stanev, S.; Rusanov, K.; Atanassov, I. SRAP Markers for Genetic Diversity Assessment of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Varieties and Breeding Lines. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2020, 34, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D.; Bai, H.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Shi, L. The Chromosome-Based Lavender Genome Provides New Insights into Lamiaceae Evolution and Terpenoid Biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banikamali, M.; Soltanloo, H.; Ramezanpour, S.S.; Yamchi, A.; Sorahinobar, M. Identification of Salinity Responsive Genes in Lavender through CDNA-AFLP. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 28, e00520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USLGA. The United States Lavender Growers Association—Lavender Varieties. Available online: https://www.uslavender.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=73:lavender-varieties&catid=24:lavender-101&Itemid=138 (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Cavanagh, H.M.A.; Wilkinson, J.M. Lavender Essential Oil: A Review. Aust. Infect. Control 2005, 10, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu (Lupoae), D.; Alexe, P.; Stănciuc, N. Overview on the Potential Role of Phytochemicals from Lavender as Functional Ingredients. Ann. Univ. Dunarea Jos Galati Fascicle VI-Food Technol. 2020, 44, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendi, A.; Irakli, M.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Bouloumpasi, E.; Biliaderis, C.G. Phenolic Extracts from Solid Wastes of the Aromatic Plant Essential Oil Industry: Potential Uses in Food Applications. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, I.; Denkova, R.; Chochkov, R.; Teneva, D.; Denkova, Z.; Dessev, T.; Denev, P.; Slavov, A. Effect of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) and Melissa (Melissa Officinalis) Waste on Quality and Shelf Life of Bread. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamróz, E.; Juszczak, L.; Kucharek, M. Investigation of the Physical Properties, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Ternary Potato Starch-Furcellaran-Gelatin Films Incorporated with Lavender Essential Oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Foppa, I.; Liebowitz, R.; Nelson, J.; Smith, M.; Sollars, D.; Ulbricht, C. Monograph from Natural Standard: Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Miller). J. Herb. Pharmacother. 2009, 4, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marovska, G.; Vasileva, I.; Petkova, N.; Ognyanov, M.; Gandova, V.; Stoyanova, A.; Merdzhanov, P.; Simitchiev, A.; Slavov, A. Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Industrial by-Products as a Source of Polysaccharides. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusinowska, R.; Śmigielski, K.; Stobiecka, A.; Kunicka-Styczyńska, A. Hydrolates from Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia)—Their Chemical Composition as Well as Aromatic, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śmigielski, K.B.; Prusinowska, R.; Krosowiak, K.; Sikora, M. Comparison of Qualitative and Quantitative Chemical Composition of Hydrolate and Essential Oils of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2013, 25, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woronuk, G.; Demissie, Z.; Rheault, M.; Mahmoud, S. Biosynthesis and Therapeutic Properties of Lavandula Essential Oil Constituents. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusinowska, R.; Smigielski, K.B. Composition, Biological Properties and Therapeutic Effects of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia L.). A Review. Herba Pol. 2014, 60, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage-Meessen, L.; Bou, M.; Sigoillot, J.-C.; Faulds, C.B.; Lomascolo, A. Essential Oils and Distilled Straws of Lavender and Lavandin: A Review of Current Use and Potential Application in White Biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 3375–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantinescu, E.; Nițu (Năstase), S.; Boruz, V.; Ștefan, I.O. Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Medicinal Alternative Species in the Structure of Crops in Agricultural Farms, in the Context of Climate Change. Ann. Univ. Craiova-Agric. Mont. Cadastre Ser. 2022, 52, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Guyot-Declerck, C.; Renson, S.; Bouseta, A.; Collin, S. Floral Quality and Discrimination of Lavandula Stoechas, Lavandula angustifolia, and Lavandula angustifolia × latifolia Honeys. Food Chem. 2002, 79, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giray, F.H.; Kadakoğlu, B.; Çetin, F.; Bamoi, A.G.A. Rural Tourism Marketing: Lavender Tourism in Turkey. Ciênc. Rural 2019, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, V.R.; Grekov, D.F.; Kisyov, V.K.; Ivanov, K.I. Potential of Lavender (Lavandula Vera L.) for Phytoremediation of Soils Contaminated with Heavy Metals. Int. J. Agric. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 9, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlihor, R.M.; Roșca, M.; Hagiu-Zaleschi, L.; Simion, I.M.; Daraban, G.M.; Stoleru, V. Medicinal Plant Growth in Heavy Metals Contaminated Soils: Responses to Metal Stress and Induced Risks to Human Health. Toxics 2022, 10, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Verma, R.K. Essential Oil Bearing Aromatic Plants: Their Potential for Sequestering Carbon in Marginal Soils of India. Soil Use Manag. 2020, 36, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Tomar, J.M.S.; Kaushal, R.; Kadam, D.M.; Rathore, A.C.; Mehta, H.; Ojasvi, P.R. Aromatic Plants Based Environmental Sustainability with Special Reference to Degraded Land Management. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2021, 22, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najar, B.; Pistelli, L.; Fratini, F. Exploitation of Marginal Hilly Land in Tuscany through the Cultivation of Lavandula angustifolia Mill.: Characterization of Its Essential Oil and Antibacterial Activity. Molecules 2022, 27, 3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, S.A.; Kasraie, P.; Oveysi, M.; Tohidi Moghadam, H.R.; Ghooshchi, F. Mitigating the Adverse Effects of Salinity Stress on Lavender Using Biodynamic Preparations and Bio-Fertilizers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 183, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar, M.; Grbić, M.L.; Džamić, A.; Unković, N.; Ristić, M.; Jelikić, A.; Vukojević, J. Antifungal Activity of Selected Essential Oils and Biocide Benzalkonium Chloride against the Fungi Isolated from Cultural Heritage Objects. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2014, 93, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukošiūtė, S.; Šernaitė, L.; Morkeliūnė, A.; Rasiukevičiūtė, N.; Valiuškaitė, A. The Effect of Lamiaceae Plants Essential Oils on Fungal Plant Pathogens in vitro. Agron. Res. 2020, 8, 2761–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagáň, Ľ.; Apacsová Fusková, M.; Hlávková, D.; Skoková Habuštová, O. Essential Oils: Useful Tools in Storage-Pest Management. Plants 2022, 11, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adaszyńska-Skwirzyńska, M.; Szczerbińska, D. The Effect of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) Essential Oil as a Drinking Water Supplement on the Production Performance, Blood Biochemical Parameters, and Ileal Microflora in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, M.; Shabunin, S.V.; Vatnikov, Y.A.; Kulikov, E.V.; Adineh, H.; Khademi Hamidi, M.; Hoseini, S.M. Effects of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) Extract Inclusion in Diet on Growth Performance, Innate Immunity, Immune-Related Gene Expression, and Stress Response of Common Carp, Cyprinus Carpio. Aquaculture 2020, 515, 734588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenubi, O.T.; Ahmed, A.S.; Fasina, F.O.; McGaw, L.J.; Eloff, J.N.; Naidoo, V. Pesticidal Plants as a Possible Alternative to Synthetic Acaricides in Tick Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 779–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, A.; Caporali, F. Effects of Essential Oils of Cinnamon, Lavender and Peppermint on Germination of Mediterranean Weeds. Allelopathy J. 2010, 25, 441–452. [Google Scholar]

- Eyupoglu, S.; Merdan, N. Physicochemical Properties of New Plant Based Fiber from Lavender Stem. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 9248–9258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirvaityte, J.; Siugzdaite, J.; Valeika, V. Application of Commercial Essential Oils of Eucalyptus and Lavender as Natural Preservative for Leather Tanning Industry. Rev. Chim. 2011, 62, 884–893. [Google Scholar]

- Cherver, T.; Gonçalves, A.; Lepeule, C. Farm Certification Schemes for Sustainable Agriculture—State of Play and Overview in the EU and in Key Global Producing Countries, Concepts and Methods; European Parliment—AGRI Committe: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Agriculture and Rural Development Organic Production and Products—European Union Regulations. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/farming/organic-farming/organic-production-and-products_en (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2014.

- Essential Oils—ECHA. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/support/substance-identification/sector-specific-support-for-substance-identification/essential-oils (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I. An Overview of the Biological Effects of Some Mediterranean Essential Oils on Human Health. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, e9268468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.K.T.; Hadji-Minaglou, F.; Antoniotti, S.; Fernandez, X. Authenticity of Essential Oils. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 66, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounaas, K.; Bouzidi, N.; Daghbouche, Y.; Garrigues, S.; de la Guardia, M.; El Hattab, M. Essential Oil Counterfeit Identification through Middle Infrared Spectroscopy. Microchem. J. 2018, 139, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Ali, Z.; Avonto, C.; Khan, I.A. A Novel Approach for Lavender Essential Oil Authentication and Quality Assessment. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 199, 114050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisserand, R.; Young, R. Essential Oil Safety: A Guide for Health Care Professionals; Elsevier Health Sciences: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-7020-5434-1. [Google Scholar]

- Prashar, A.; Locke, I.C.; Evans, C.S. Cytotoxicity of Lavender Oil and Its Major Components to Human Skin Cells. Cell Prolif. 2004, 37, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, J.; Hires, C.; Dunne, E.; Baker, C. The Relationship between Lavender and Tea Tree Essential Oils and Pediatric Endocrine Disorders: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 49, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Détár, E.; Németh, É.Z.; Gosztola, B.; Demján, I.; Pluhár, Z. Effects of Variety and Growth Year on the Essential Oil Properties of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) and Lavandin (Lavandula x Intermedia Emeric Ex Loisel.). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 90, 104020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valchev, H.; Kolev, Z.; Stoykova, B.; Kozuharova, E. Pollinators of Lavandula angustifolia Mill., an Important Factor for Optimal Production of Lavender Essential Oil. BioRisk 2022, 17, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, M.M.A.; Zhang, C.; Ghaleb, A.D.S.; Li, J.; Nagi, A.; Majeed, H.; Bakry, A.M.; Haider, J.; Xu, Z.; Tong, Q. Techno-Functional Properties and Sustainable Application of Nanoparticles-Based Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil Fabricated Using Unsaturated Lipid-Carrier and Biodegradable Wall Material. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 136, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alteriis, E.; Maione, A.; Falanga, A.; Bellavita, R.; Galdiero, S.; Albarano, L.; Salvatore, M.M.; Galdiero, E.; Guida, M. Activity of Free and Liposome-Encapsulated Essential Oil from Lavandula angustifolia against Persister-Derived Biofilm of Candida Auris. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.-H.; Lai, K.-S.; Lim, S.-H.E. Combination Therapy Involving Lavandula angustifolia and Its Derivatives in Exhibiting Antimicrobial Properties and Combatting Antimicrobial Resistance: Current Challenges and Future Prospects. Processes 2021, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Country | Cultivars and Source |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Europe | Bulgaria | ‘Hemus’, ‘Yubileyna’, ‘Druzhba’, ‘Sevtopolis’ [86] |

| Czechia | ‘Krajová’, ‘Beta’ [87] | |

| Hungary | ‘Budakalászi’, ‘Hidcote’, ‘Maillette’, ‘Munstead’ [72] | |

| Moldova | ‘Aroma Unica’ [88]; ‘Moldoveanca 4’, ‘Vis Magic 10’, ‘Alba 7’ [83] | |

| Poland | ‘Hidcote Blue Strain’, ‘Hidcote Blue’ [89] | |

| Romania | ‘De Moara Domnească’ [5]; ‘Codreanca’ [90]; ‘Maillette’, ‘Vera’ [91]; ‘Moldoveanca 4’ [92]; ‘Alba 7’ and ‘Vis Magic 10’ [93]; ’Buena Vista’, ‘Hidcote’ [64]; ‘Provence Blue’ [29]; ‘Sevtopolis’ [71]; | |

| Russia | ‘Prima’, ‘Record’, ‘Sineva’ [94]; ‘Voznesenskaya 34’, ‘Rannyaya’, ‘Yuzhanka’, ‘Voznesenskaya Aroma’ [95] | |

| Ukraine | ‘Record’, ‘Sineva Nadii’, ‘Zmijuchka’, ‘Pink Flamingo’, ‘No. 463-20’, ‘No. 1-469’, ‘1-2-20’ [96] | |

| Southern Europe | Greece | ‘Etherio’ [82] |

| Italy | ‘Maillette’ [97]; ‘Rosa’ [98] | |

| Western Europe | France | ‘Matheronne’, ‘Maillette’, ‘Diva’, ‘Rapido’ [25] |

| Northern Europe | United Kingdom | ‘Ashdown Forest’, ‘Blue Cushion’, ‘Miss Donnington’, ‘Fring’, ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Heacham Blue’, ‘Hidcote’, ‘Imperial Gem’, ‘Loddon Pink’, ‘Loddon Blue’, ‘Munstead’, ‘Nana Alba’, ‘No. 6’, ‘No. 9’, ‘Princess Blue’, ‘Rosea’, ‘Royal Blue’ [7] |

| Worldwide | Australia | ‘Tuulong’, ‘Lavender Lady’ [7] |

| China | ‘Jingxun 2’ [99] | |

| Japan | ‘Hayasaki’, ‘Youtei’, ‘Hanamoiwa’, ‘Okamurasaki’ [7] | |

| New Zealand | ‘Blue Mountain’, ‘Avice Hill’ [7] | |

| Turkey | ‘Raya’, ‘Munstead’, ‘Vera’, ‘Silver’ [100] | |

| United States | ‘Betty’s Blue’, ‘Buena Vista’, ‘Lisa Marie’, ‘Royal Velvet’, ‘Gray Lady’, ‘Irene Doyle’, ‘Lady’ [7] |

| Recommended Uses | Cultivars | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Essential oil | ‘Maillette’ | standard in France and ISO |

| Fresh cut flowers | ‘Buena Vista’ | rebloomer, long flowering |

| Crafts | ‘Folgate’ | retains color when it dries, good for wreaths |

| Culinary buds | ‘Royal Velvet’, ‘Melissa’, ‘Betty’s Blue’ | mild/gentle flavor, good for deserts, food and tea |

| Dried buds | ‘Buena Vista’ | mild scent; for pot-pourri and sachets |

| Landscape | ‘Munstead’ | small compact bush, strong scent, suitable for pots |

| Compound | European Pharmacopoeia [75] | ISO 3515:2002 [38] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Genotype | Clonally Propagated Lavender | |||||

| France (from Seed) | France ‘Maillette’ | Bulgaria | Russia | Other Origins | ||

| lavandulyl acetate | >0.2 | >2 | <1.3 | 2–5 | 1–3.5 | <8 |

| lavandulol | >0.1 | >0.3 | <0.5 | >0.3 | >0.1 | <3 |

| 3-octanone | 0.1–5 | traces; <2 | 1–2.5 | 0.2–1.6 | <0.6 | <3 |

| terpinen-4-ol | 0.1–8 | 2–6 | 0.5–1.5 | 2–5 | 1.2–5 | <8 |

| linalol | 20–45 | 25–38 | 30–45 | 22–34 | 20–35 | 20–43 |

| linalyl acetate | 25–47 | 25–45 | 33–46 | 30–42 | 29–44 | 25–47 |

| limonene | <1 | <0.5 | <0.3 | <0.6 | <1 | <1 |

| camphor | <1.2 | traces; <0.5 | <1.2 | <0.6 | <0.6 | <1.5 |

| α-terpineol | <2 | <1 | 0.5–1.5 | 0.8–2 | 0.5–2 | <2 |

| 1,8-cineole | <2.5 | <1 | <0.5 | <2 | <2.5 | <3 |

| β-phellandrene | n/a | traces; <0.5 | <0.2 | <0.6 | <1 | <1 |

| cis-β-ocimene | n/a | 4–10 | <2.5 | 3–9 | 3–8 | 1–10 |

| trans-β-ocimene | n/a | 1.5–6 | <2 | 2–5 | 2–5 | 0.5–6 |

| (S)-linalyl acetate | <1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| (S)-linalol | <12 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crișan, I.; Ona, A.; Vârban, D.; Muntean, L.; Vârban, R.; Stoie, A.; Mihăiescu, T.; Morea, A. Current Trends for Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Crops and Products with Emphasis on Essential Oil Quality. Plants 2023, 12, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020357

Crișan I, Ona A, Vârban D, Muntean L, Vârban R, Stoie A, Mihăiescu T, Morea A. Current Trends for Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Crops and Products with Emphasis on Essential Oil Quality. Plants. 2023; 12(2):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020357

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrișan, Ioana, Andreea Ona, Dan Vârban, Leon Muntean, Rodica Vârban, Andrei Stoie, Tania Mihăiescu, and Adriana Morea. 2023. "Current Trends for Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Crops and Products with Emphasis on Essential Oil Quality" Plants 12, no. 2: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020357

APA StyleCrișan, I., Ona, A., Vârban, D., Muntean, L., Vârban, R., Stoie, A., Mihăiescu, T., & Morea, A. (2023). Current Trends for Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Crops and Products with Emphasis on Essential Oil Quality. Plants, 12(2), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020357