Abstract

We compiled an updated database of all Agave species found in Mexico and analyzed it with specific criteria according to their biological parameters to evaluate the conservation and knowledge status of each species. Analyzing the present status of all Agave species not only provides crucial information for each species, but also helps determine which ones require special protection, especially those which are heavily used or cultivated for the production of distilled beverages. We conducted an extensive literature review search and compiled the conservation status of each species using mainstream criteria by IUCN. The information gaps in the database indicate a lack of knowledge and research regarding specific Agave species and it validates the need to conduct more studies on this genus. In total, 168 Agave species were included in our study, from which 89 are in the subgenus Agave and 79 in the subgenus Littaea. Agave lurida and A. nizandensis, in the subgenus Agave and Littaea, respectively, are severely endangered, due to their endemism, lack of knowledge about pollinators and floral visitors, and their endangered status according to the IUCN Red List. Some species are at risk due to the loss of genetic diversity resulting from production practices (i.e., Agave tequilana), and others because of excessive and unchecked overharvesting of wild plants, such as A. guadalajarana, A. victoriae-reginae, A. kristenii, and others. Given the huge economic and ecological importance of plants in the genus Agave, our review will be a milestone to ensure their future and continued provision of ecosystem services for humans, as well as encouraging further research in Agave species in an effort to enhance awareness of their conservation needs and sustainable use, and the implementation of eco-friendly practices in the species management.

1. Introduction

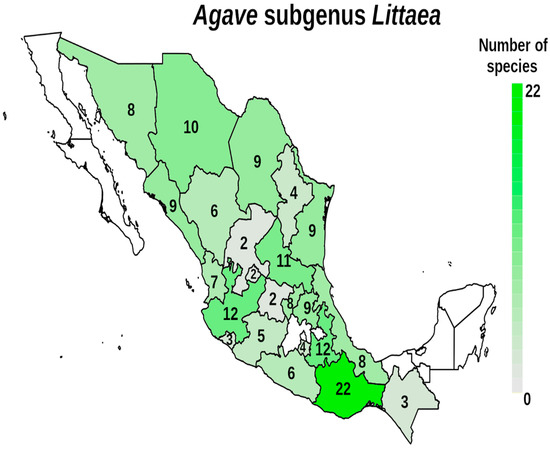

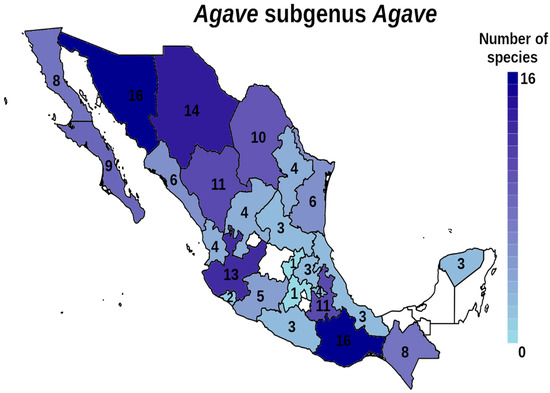

Mexico is well-known for its high levels of biodiversity, and agaves or magueyes belonging to the family Asparagaceae are a very important example of that biodiversity. The genus Agave is endemic to the American continent (although introduced Agave are now found in many places), mainly in arid and semi-arid areas of Mexico. There are approximately 200 species of Agave, of which 166 are distributed in Mexico and 119 are endemic [1,2]. The subgenus Littaea contains about 78 species (Figure 1) while the subgenus Agave includes around 92 species (Figure 2), making it the subgenus with the greatest distribution throughout Mexico [3]. Subgenera are distinguished by their large inflorescence, either a spike for the subgenus Littaea species or branched with panicles for Agave [4]. The succulence and rigidity of its leaves for water storing, the efficient water absorption system throughout its roots and the limited water loss through transpiration, are some of the adaptations agaves possess for life in dry ecosystems. Their CAM-type photosynthetic metabolism (Crassulaceae Acid Metabolism) allows them to grow in poor soil and weather conditions, withstanding severe environmental pressures [2]. These morphological and physiological adaptations have allowed agaves to live in a wide variety of environments, expanding their geographical distribution [3,5].

Figure 1.

Distribution and number of species of the Agave subgenus Littaea by Mexican states. Color intensity is proportional to the number or species.

Figure 2.

Distribution and number of species of the Agave subgenus Agave by Mexican states. Color intensity is proportional to the number or species.

From a historical perspective, agaves have played a crucial role in the daily lives of human beings, providing a wide range of resources, from food and the production of alcoholic beverages to a source of fiber. The procurement of fibers from these plants was perhaps the first use given to agaves, since it was used for clothing, baskets, nets, rope, and more [4]. Several species have been used for food, the flowers boiled and eaten, and earthen ovens to cook agave cores or “piñas”. This method was an ancestral practice that is nowadays utilized for the production of distilled beverages [6]. The use of Agave to produce the distilled liquors known today as tequila, mezcal, and others was apparently not known to past civilizations, since distillation was introduced after the conquest, but the production of pulque and mead or “aguamiel” has been used since pre-Hispanic times, making these beverages the ones that promoters of the agave cultivation in Mexican civilizations. Currently over 70 traditional uses have been known and recorded for the species of the genus Agave [7], classified under 22 categories [8].

Additionally, the residues derived from the elaboration of distilled beverages, including the flowering stalks, bagasse (solid waste) and stillage (liquid waste) have various uses. The leaves, removed from the core of the agave rosette are commonly used in the preparation of Mexican dishes, such as in the “barbacoa” where the leaves are roasted and used to wrap the meat with spices for cooking while bagasse and stillage residues have been proven as a good alternative for compost [9]. These wastes are polysaccharide-rich byproducts that can be used for the production of fructans, which can be used in supplement products to treat diabetes or obesity [2].

Agave fibers have a wide variety of uses: as food for livestock and the production of different handcrafts, or common products such as nets, ropes or textiles. In rural areas, agaves are widely used as living fences to keep livestock away from crops or houses, to indicate roads, and even for construction [10]. Agave sisalana (sisal) and A. fourcroydes (henequen) are the most useful species for obtaining fiber and are widely used for structural construction material. Agave sisalana, for example, is still a major source of fiber in plantations in many countries of Latin America, Asia and Africa [11]. Fiber obtained from agaves is having a greater advantage over synthetic fibers nowadays as they are more affordable, with lower density, ecofriendly, and can be recycled [12].

Agaves are greatly known in the distilled beverages industry. Tequila and mezcal have become symbols of Mexico throughout the world, while pulque, the pre-Hispanic fermented alcoholic beverage, is considered to be one of the first traditional drinks originated from agave. Bacanora and raicilla are some of the least known agave distillates as they have a low level of industrialization compared to the rest of the distilled beverages [6,8].

Pulque is a white fermented beverage that can be obtained from a wide variety of agave species such as A. atrovirens, A. americana, A. salmiana and A. mapisaga. This drink is made through the fermentation of mead or aguamiel, a sugary extract that accumulates inside the core of the ripe agave and that can also be consumed fresh without fermenting [13]. Pulque is consumed both in rural areas, where it may even be considered as an important meal in a daily diet, and in urban areas, where it can be found in pulquerias and Mexican restaurants. Currently, the consumption of pulque is promoted partly so as not to lose a pre-Hispanic tradition [14,15].

Tequila is considered the most representative drink in Mexico, a job and currency generator of foreign exchange for its sales abroad. In 2016, Jalisco obtained $1.6 billion dollars in tequila exports abroad growing to $2.3 billion dollars in 2020 while the industry generated 70,000 jobs [16,17]. Tequila is obtained from Agave tequilana or blue agave, which can only be grown in regions known as Denomination of Origin of Tequila (DOT). This includes the states of Jalisco (126 municipalities) with 90% of production, Michoacán (30 municipalities), Tamaulipas (11 municipalities), Nayarit (eight municipalities) and Guanajuato (seven municipalities) [18]. Since A. tequilana is not common in the wild, tequila is sourced entirely from cultivated plants. In addition, to avoid a perceived waste if the plants are allowed to flower, agave fields are re-planted with young agave plants that are the result of asexual reproduction from a subset of the original plants in the field, thus resulting in a severe loss of genetic diversity generation after generation [19]. In addition, tequila has the most industrialized production processes of all distilled beverages originated from agave. The use of autoclaves (steam-fueled pressure-cookers) to cook the heads of A. tequilana is the most production-efficient method for Agave distillates, having control of the pressure-temperature ratio and its highly reduced cooking time compared to handcrafted methods [2,20,21]. Yet this process has serious costs for the quality and organoleptic characteristics of the final product as using diffusers for the thorough extraction of the sugars causes the addition of other secondary metabolites to the must, the fluid subjected to distillation, lowering the quality of the final product [22].

Mezcal, unlike tequila, is obtained from more than 50 agave species mostly found in the wild in Mexico. In 2007, Colunga-GarcíaMarín stated that at least 56 taxa are used for the production of this beverage. There is a wide diversity in mezcal production, which is due both to the diversity of the agave species used, and the variety of production processes. Thus, while tequila production is standardized and industrialized, the production of mezcal is generally handcrafted varying between regions so its flavor, aroma, alcohol content and quality depends on the region of production, the species of agave used and the mezcal manufacturer in charge of it [23]. Although mezcal production is generally handcrafted, industrial and so-called “ancestral” production processes are also used. Yet generally, traditional mezcal usually uses pit ovens or masonry pools for fermentation, grinding is carried out with tahona or Chilean mill, and distillation is made in copper stills or clay pots.

Bacanora is the local mezcal of the state of Sonora and is obtained from a variety of A. angustifolia, from which mezcal espadín is derived [24]. The variety A. angustifolia var. pacifica differs mainly in the cultivation of the agave as it is a wild agave with no use of fertilizers or pesticides and its distillation replaces the copper stills with metal barrels heated with mesquite wood. Currently, few producers are dedicated to the production and marketing of bacanora [25,26].

Coastal raicilla is obtained from A. rhodacantha and A. angustifolia, while the highland raicilla is acquired from A. maximiliana. This was a popular mezcal among miners of the mountains of the Sierra Madre Occidental of Jalisco and its production is currently only locally handcrafted by around 70 producers in 2014 [2,27].

The consumption of agave-derived products has increased in recent years and therefore its demand is rapidly growing nationally and internationally, mainly that of the distilled beverages. This demand implies a greater quantity of supply and modern technology in production processes, thus decreasing traditional methods and craftsmanship. That being said, it is important to emphasize that depending upon the Agave species and the local conditions of soil, humidity and nutrients, it may take between seven, ten, or 36 years or more (i.e., A. tequilana, A. potatorum, A. seemanniana, respectively) [4,28,29,30] for them to reach harvest maturity, so if sustainable practices and adequate environments are not secured for wild individuals, the future of their populations could be in jeopardy.

In the case of mezcal, this evolving tradition and increased demand has forced some producers to incorporate new technologies and infrastructures to be capable of adapting to a rapidly growing and demanding market, yet if proper management practices of agave populations are lost, it could result in a reduction of population size and genetic variability. Species such as A. tequilana for making tequila or A. fourcroydes to manufacture henequen, use clonal propagation, where suckers of the same genotype are grown and thus their genetic diversity is eroded generation after generation. The loss of genetic diversity carries a reduction of its adaptability to environmental and climate changes, pathogens and pests [2,23,30,31,32,33].

As with any species, genetic diversity of Agave species is crucial to secure its evolutionary processes and adapt to a changing environment. Most species of Agave exhibit sexual reproduction and are usually cross-pollinated, contributing to greater genetic diversity in the wild. However, many species also exhibit asexual reproduction, which can also be useful if there are few pollinators available, but it could be detrimental to genetic diversity in agave crops [23,30,31].

The objective of this study is to describe an updated compilation of the species of both subgenera of the genus Agave (Agave and Littaea) found in Mexico, analyzing available data for each species on its uses, biology and extinction risk, and suggesting alternative strategies to avoid extinction or detrimental uses of particular species.

2. Methodology and Analysis

A review using different digital searches, with emphasis in databases, dissertations and literature in Spanish, several English digital researches, Howard Scott Gentry’s physical Agaves of Continental North America book and previous reviews published on the Agave species found in Mexico divided by the two subgenera, Agave and Littaea, was carried out using the following criteria: distribution in Mexico, common names, pollinators and floral visitors, common uses, type(s) of reproduction, endemism, extinction risk according to the IUCN Red List [34], subspecies, and a calculation was made, based on the total importance of each species supported by the parameters mentioned above. The five criteria regarding the importance score of each species have similar weight and are explained below. It is important to emphasize that although the species from the subgenus Littaea are of less economic importance than the subgenus Agave, it is relevant to include them in the analysis because of their biological importance.

2.1. Risk Level Based on the IUCN Red List

- CR: Critically Endangered;

- EN: Endangered;

- VU: Vulnerable;

- EW: Extinct in the Wild;

2.2. Endemism in Mexico

- E: Endemic;

- NE: Not endemic;

2.3. General Uses

- The species has anthropogenic use;

- The species has no uses;

2.4. Knowledge of Pollinator, Floral Visitor and/or Reproduction

- Assuming that less knowledge puts the species at greater risk than more known species

Index: IUCN Red List Abbreviations for Table 1 and Table 2.

| IUCN Red List |

| NT: Near Threatened VU: Vulnerable EN: Endangered CR: Critically Endangered EW: Extinct in the Wild |

Statistical analyzes and figures were made with R y4.2.1 [35]. Graphics were made with the package ggplot 2 [36]. A summary of the analysis of both subgenera is listed below with Table 1 showing the subgenus Agave and Table 2 the subgenus Littaea. The last column titled Importance Score is based on five criteria obtained from the analysis, which are considered to be very relevant regarding the conservation status and biological environment of each species; the higher the number, the greater the extinction risk a species faces.

Table 1.

Species of the subgenus Agave with a summary of specific data according to their conservation status and biological environment.

Table 1.

Species of the subgenus Agave with a summary of specific data according to their conservation status and biological environment.

| Species | Common Names | Uses | Pollinator | Floral Visitor | Reproduction | Distribution | IUCN Red List Category | Importance Score | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agave abisaii * A. Vázquez and Nieves | Medical use (anti-inflammatory) | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae Choeronycteris mexicana | Sexual: Pollination | Jalisco | EN | 7 | [34,37,38] | ||

| Agave aktites Gentry | Food | Sinaloa, Sonora | VU | 4 | [4,34,38] | ||||

| Agave americana L. | Americano, Arroqueño (Oaxaca), Blanco, Castilla (Oaxaca), Cenizo (Tamaulipas), De Pulque (Oaxaca), Ruqueño (Oaxaca), Serrano, Sierra Negra (Oaxaca), T’ax’uada (otomi), Teometl (náhuatl), Yavi-Cuan (mixteco), Agave amarillo, Maguey serrano, Maguey cebra, Maguey cenizo, Maguey chichimeco, Maguey chino, Maguey pinto | Pulque production, distilled beverage production, ornament, textile source, food | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Leptonycteris nivalis Choeronycteris mexicana | Asexual: clonal sexual: pollination | Chihuahua, Oaxaca, Coahuila, Jalisco, South EU (Texas) | 3 | [4,6,13,38,39] | ||

| Agave andreae Sahagún and A. Vázquez | Maguey de Piedra | Ornament | Michoacán | VU | 7 | [34,37,38,39] | |||

| Agave angustifolia Haw. | Espadilla (Puebla), Espadín (Oaxaca), Ixtero verde, Amole, Bacanora, Chacaleño (Durango), Chelem (maya), Cincoañero (Oaxaca), Delgado (Guerrero, Oaxaca), Doba-yej (zapoteco), Gubuk (Chihuahua y Durango), Gusime (Chihuahua), Guvúkai (Chihuahua y Durango), Hamoc (seri), Juya-cuul, Ki’mai (Chihuahua y Durango), Kuúri (Chihuahua), Lineño (Jalisco), Maguey de Campo, Pelón Verde (Oaxaca), Tepemete (Durango), Yavi-incoyo, Zapupe, Henequén, Maguey de flor, Maguey de ixtle | Distilled beverage production, fiber source | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae Choeronycteris mexicana | Mimus saturninus, woodpeckers, hummingbirds, night moths | Sexual: pollination asexual: clonal bulbils | Sonora, Sinaloa, Nayarit, Jalisco, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Costa Rica | 4 | [4,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | |

| Agave antillarum Descourt. | Maguey Antillano | Dominican Republic | 2 | [38,45] | |||||

| Agave applanata Lem. ex Jacobi | Ki’may, Maguey blanco, Maguey de Castilla, Maguey de ixtle | Pulque production, medicinal use, fiber source, food | Sexual: seeds | Chihuahua, Durango, Oaxaca, Puebla, Tlaxcala, Veracruz | 3 | [4,13,38,40] | |||

| Agave asperrima Jacobi | Maguey Bruto | Food, mead production, distilled beverage production, fiber source | Asexual: clonal sexual: seeds | Coahuila, Durango, Nuevo León, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas | 3 | [38,40,41,42,45] | |||

| Agave atrovirens Karw. | Agave pulquero, Flor de jiote, Flor de maguey, Flor de mezcal, Flor de pitol, Flor de quiote, Flor de sotol, Maguey de montaña, Maguey de pulque, Maguey manso, Maguey de cumbre, Tepeme | Mezcal production, fiber source, living fence | Asexual: clonal sexual: seeds | Puebla, Oaxaca | 3 | [4,13,38] | |||

| Agave aurea Brandegee | Lechuguilla, Lechuguilla mezcal, Maguey | Ornament, fiber source | Asexual: clonal | Baja California Sur | 5 | [38,44,46,47] | |||

| Agave avellanidens Trel. | Ornament | Asexual: clonal | Baja California | NT | 5 | [34,38,46,47] | |||

| Agave azurea R. H. Webb and G. D. Starr | Sexual: seeds | Baja California Sur | VU | 4 | [34,38,47] | ||||

| Agave bovicornuta Gentry | Lechuguilla de la Sierra (Sonora), Masparillo (Durango) Cerial | Ornament, food, mezcal production (not so common), fiber source | Sexual: pollination, seeds | Sonora, Sinaloa, Chihuahua | VU | 4 | [4,34,38,39,40] | ||

| Agave cantala(Haw.) Roxb. ex Salm-Dyck | Cincoañero (Oaxaca), Maguey del Cinco (Oaxaca) Henequén | Fiber source, fistilled beverage production | Asexual: clonal | Oaxaca, Jalisco | 3 | [4,34,38,39,40] | |||

| Agave capensis Gentry | Mescalito | Food | Baja California | EN | 8 | [4,34,38,39,40] | |||

| Agave chrysantha Peebles | Food, fiber source | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Apis mellifera | Bats, birds, insects | Sexual: pollination seeds asexual: clonal | Sonora, Southwest EU (Arizona) | 2 | [30,38,40,42,44] | ||

| Agave colorata Gentry | Ceniza (Sonora), Haamjö, Caacöl | Food, mead production, mezcal production, ornament | Leptonycteris, hummingbirds | Hummingbirds | Sexual: pollination, seeds asexual: clonal | Sinaloa, Sonora | 2 | [4,38,39,40,44] | |

| Agave congesta Gentry | Maguey Tzotzil | Ornament | Sexual: Seeds | Chiapas | 6 | [4,38,40,48,49,50] | |||

| Agave cupreata Trel. and A. Berger | Papalometl, Papalote (Guerrero), Ancho, Chino (Michoacán), Cimarrón, Tuchi, Yaabendisi (mixteco), Maguey bravo, Tobalá | Mezcal production, food, mead production | Sexual: seeds | Guerrero, Michoacán | EN | 5 | [34,38,39,40,41] | ||

| Agave datylio F. A. C. Weber | Ornament | Asexual: clonal | Baja California Sur | 5 | [4,38,44,47] | ||||

| Agave decipiens Baker | Asexual: clonal | Southeast EU (Florida), Yucatán | VU | 2 | [4,34,38,45] | ||||

| Agave delamateri W. C. Hodgs and Slauson | Food, fiber source | Birds, insects | Asexual: clonal | Southwest EU (Arizona) | 5 | [38,51] | |||

| Agave deserti (complex) Engelm. | Maguey del desierto | Ornament, food, fiber source, mead source | Hummingbirds, insects | Sexual: seeds asexual: clonal | Baja California Sonora Southwest EU | 3 | [4,38,40,44,47,52] | ||

| Agave deserti Agave cerulata (complex) Trel. | Mescal | Fiber source, food, Mead production, distilled beverage production | Baja California, Sonora | 4 | [38,40,44,47] | ||||

| Agave deserti Agave subsimplex (complex) Trel. | A’amxw | Food | Bombus, Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Lepidoptera | Bats | Sexual: pollination | Sonora | VU | 5 | [34,38,40,44,53] |

| Agave desmettiana Jacobi | Maguey de pita | Ornament, mead production, distilled beverage production | Glossophaga soricina | Sexual: pollination asexual: clonal | Sinaloa, Southwest EU (California) | 3 | [4,38,40,54] | ||

| Agave durangensis Gentry | Cenizo (Durango), Bayuza | Ornament, mezcal production, food | Sexual: seeds asexual: clonal | Durango, Zacatecas | 3 | [4,38,39,40,55] | |||

| Agave flexispina Trel. | Ornament | Chihuahua, Durango, Zacatecas | VU | 5 | [4,34,38] | ||||

| Agave fortiflora Gentry | Haamjö, Caacöl | Food, mead production | Asexual: clonal | Sonora | 5 | [4,38,40] | |||

| Agave fourcroydes Lem. | Henequén, Jenequén, Maguey sisal | Fiber source, ornament, food | Asexual: clonal nulbils | Yucatán, Cuba | 3 | [4,38,40,55] | |||

| Agave gentryi B. Ullrich | Maguey del Bosque | Food, mead production, fiber source | Chiroptera | Sexual: pollination | Nuevo León, Coahuila, Tamaulipas, Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Hidalgo, Mexico, Puebla | 3 | [38,40,56,57] | ||

| Agave gigantensis Gentry | Ornament, mezcal production | Sexual: seeds | Baja California Sur | 5 | [4,38,40,46] | ||||

| Agave gracilipes Trel. | Maguey de Pastizal | Chihuahua, South EU (Texas), Nuevo Mexico | 2 | [4,38] | |||||

| Agave grijalvensis B. Ullrich | Maguey del Grijalva | Ornament, food | Sexual: seeds | Chiapas | EN | 7 | [34,38,58] | ||

| Agave guadalajarana Trel. | Mascarreño | Distilled beverage production, ornament, medical use | Sexual: seeds | Jalisco | EN | 7 | [4,34,38,40,42] | ||

| Agave gypsophila Gentry | Maguey de Ixtli, quiote | Used for rural house construction | Asexual: clonal | Guerrero | CR | 9 | [34,37,38,49,50] | ||

| Agave havardiana Trel. | Maguey norteño | Mezcal production | Leptonycteris nivalis, Choeronycteris mexicana | Zenaida asiatica, Icterus parisorum | Sexual: pollination | Chihuahua, Coahuila, South EU (Texas) | VU | 3 | [34,38,59,60] |

| Agave hiemiflora Gentry | Wild | Sexual: seeds | Chiapas, Guatemala | 1 | [4,38,48] | ||||

| Agave hookeri Jacobi | Maguey Ixquitécatl | Pulque production, food, fiber source, living fence | Sexual: seeds asexual: clonal | Michoacán | 5 | [4,13,38,40] | |||

| Agave inaequidens K. Koch | Hocimetl (náhuatl), Largo (Michoacán), Lechuguilla | Pulque production, mezcal production, food, fiber source | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae Icterus bullockii | Apis mellifera, Vespidae, Bombus, night moth, hummingbirds, hooded warbler | Asexual: clonal sexual: pollination seeds | Jalisco, Michoacán, Colima | 2 | [13,38,39,40,42] | |

| Agave isthmensis A. García-Mend. and F. Palma | Maguey Istmeño | Ornament | Chiapas, Oaxaca | VU | 5 | [34,38] | |||

| Agave jaiboli Gentry | Food, mezcal production, fiber source | Sexual: seeds | Sonora, Chihuahua | VU | 4 | [4,34,38,40] | |||

| Agave karwinskii Zucc. | Al-mal-bi-cuish (chontal), Barril: Verde/Amarillo/Blanco, Bicuixe (Oaxaca), Cachutum (popolca), Cirial (Oaxaca), Cuishi (Oaxaca), Dob-cirial, Madrecuixe (Oaxaca), Manso, San Martinero (Oaxaca), Tobasiche (zapoteco/Oaxaca), Tripón (Oaxaca), Verde (Oaxaca), Candelilla, Candelillo, Canelillo corazón, Espadilla, Cuishe, Greñudo, Cuish, Madre cuish | Mezcal production, ornament, living fence, fiber source, food | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae | Sexual: pollination asexual: clonal | Oaxaca, Puebla, Veracruz | VU | 4 | [4,34,38,39,40,61] | |

| Agave kewensis Jacobi | Maguey del Grijalva | Food | Asexual: clonal | Chiapas | 6 | [38,40,48,49,50] | |||

| Agave kristenii A. Vázquez and Cházaro | Maguey de Piedra | Medical use, ornament | Asexual: clonal | Michoacán | CR | 8 | [34,37,38] | ||

| Agave lexii * García-Mor., García-Jim. and Iamonico | Wild | Tamaulipas | 4 | [38,62] | |||||

| Agave lurida Aiton | Maguey de la Luna | Ornament, food | Oaxaca | EW | 13 | [4,34,38,49,50] | |||

| Agave lyobaa García-Mend. and S. Franco | Maguey Coyote | Mezcal production | Oaxaca, Puebla | EN | 6 | [63] | |||

| Agave macroacantha Zucc. | Barril Verde (Oaxaca), Cincoañero (Oaxaca), Cachrolochje’, Espadilla, Estafalalate | Ornament, mead production, distilled beverage production, fiber source | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae Choeronycteris mexicana Lepidoptera (Noctuidae, Sphingidae, Microlepidoptera | Bats, Colaptes auratus, hummingbirds | Sexual: pollination asexual: clonal bulbils | Oaxaca, Puebla | EN | 4 | [34,38,39,40,42,61,64,65] |

| Agave macroculmis Tod. | Maguey verde | Food, mead production | Asexual: clonal | Chihuahua, Coahuila | 3 | [4,38,66] | |||

| Agave mapisaga Trel. | Aguamiel, Maguey manso, Maguey pulquero | Pulque production, distilled beverage production, food, fiber source, ornament, mead production | Asexual: clonal sexual: pollination | Chihuahua, Tlaxcala, Puebla, Hidalgo | 3 | [13,38,40,41,66] | |||

| Agave margaritae Brandegee | Distilled beverage production | Asexual: clonal | Baja California Sur | 5 | [38,40,47] | ||||

| Agave marmorata Roezi | Tepeztate o Tepextate (Oaxaca), Curandero, Lechuguilla, Maguey de Caballo, Pitzometl (náhuatl/Puebla), Tdu-cual ó Du-cual (zapoteco), Tecolote, Pichomel, Pitzomel, Pichometl | Mezcal production, food, mead production, fiber source | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae Choeronycteris mexicana | Bats, Colaptes auratus, hummingbirds | Sexual: pollination, seeds | Oaxaca, Puebla, Tlaxcala | 2 | [4,38,39,40,53,61] | |

| Agave maximiliana Baker | Lechuguilla (Jalisco), Manso, Masparillo (Durango), Tecolote, Raicilla | Mezcal production, mead production, food, medical use | Jalisco, Nayarit, Durango, Southwest EU (California, Arizona) | 4 | [4,38,39,40,67] | ||||

| Agave mckelveyana Gentry | Hummingbirds, Xylocopa, wasps | Sexual: pollination asexual: clonal | Southwest EU (Arizona) | 3 | [4,38,44] | ||||

| Agave montana Villareal | Ornament, mead production, fiber source | Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, Coahuila | 4 | [38,40] | |||||

| Agave moranii Gentry | Food, fiber source | Baja California | 6 | [4,38,46] | |||||

| Agave murpheyi Gibson | Agave hohokam | Food, distilled beverage production, fiber source | Sexual: seeds asexual: clonal bulbils | Sonora, Southwest EU (Arizona) | 3 | [4,38,40,51] | |||

| Agave nayaritensis Gentry | Sinaloa, Durango, Nayarit | VU | 3 | [4,34,38,48] | |||||

| Agave oroensis Gentry | Zacatecas | 2 | [4,38,40,48] | ||||||

| Agave ovatifolia G. D. Starr and Villareal | Ornament, fiber source | Nuevo León | 4 | [38,40,48] | |||||

| Agave pablocarrilloi A. Vázquez, Muñiz-Castro and Padilla-Lepe | Colima | 4 | [37,38] | ||||||

| Agave pachycentra Trel. | Oaxaca, Chiapas, Guatemala | 2 | [4,38,48] | ||||||

| Agave palmeri Engelm. | Lechuguilla (Sonora) | Food, fiber source, distilled beverage production | Bombus, Leptonycteris nivalis, Choeronycteris mexicana | Hummingbirds, insects | Sexual: pollination | Southwest EU (Arizona), Sonora | 2 | [4,30,38,39,40] | |

| Agave parrasana A. Berger | Noa | Ornament, fiber source | Coahuila | VU | 8 | [4,34,38,40,49,50] | |||

| Agave parryi Engelm. | Maguey mezcal | Mezcal production, food, fiber source, ornament | Asexual: clonal | Chihuahua, Durango, Southwest EU (Nuevo Mexico and Arizona) | 3 | [4,38,40] | |||

| Agave phillipsiana W. C. Hodgs. | Food | Asexual: clonal | Southwest EU (Arizona) | 3 | [38,68] | ||||

| Agave potatorum Zucc. | Tobalá o Dob-ala (Zapoteco/Oaxaca), Biliá (Oaxaca), Dob-be, Maguey de Monte, Papalometl (Puebla/Oaxaca), Yauiticuxi (mixteco), Arruqueño, Magueycillo | Mezcal production, food, ornament | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Leptonycteris nivalis, Apis mellifera, Bombus sp., Tabanus sp. | Bats, birds | Asexual: clonal (occasional) Sexual: pollination, seeds | Oaxaca, Puebla | VU | 3 | [4,34,38,39,40,42,69] |

| Agave pringlei Engelm. ex Baker | Asexual: clonal | Baja California | 3 | [38,47] | |||||

| Agave promontorii Trel. | Ornament | Sexual: seeds | Baja California Sur | CR | 8 | [4,34,38,47] | |||

| Agave rhodacantha Trel. | Cimarrón amarillo, Maguey de campo, Ixtéro amarillo | Mezcal production, fiber source, ornament, living fence | Sexual: seeds | Sonora, Nayarit, Jalisco, Oaxaca | 3 | [38,40,70] | |||

| Agave salmiana Otto ex Salm-Dyck | Amarillo (Puebla), Bronco Mbänuada (otomí), Cimarrón, Del Valle (Oaxaca), Doba gashon ó Doba lash (Oaxaca), Llano (Oaxaca), Maguey de Pulque, Manso, Potosino, Verde (San Luis Potosí), Xagarcia (Oaxaca) Maguey pamilla, Maguey pinto | Pulque production, mead production, mezcal production, food (“Pan de Pulque”) fiber source, ornament | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Leptonycteris nivalis, Choeronycteris mexicana, Bees, Hummingbirds | Bats, birds | Asexual: clonal sexual: pollination seeds | Puebla, Hidalgo, Chihuahua, Jalisco, Tlaxcala, Southwest EU (California and Arizona) | 2 | [4,13,15,38,39,41,42,56] | |

| Agave scabra Ortega | Lamparillo | Ornament | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Leptonycteris nivalis | Sexual: pollination asexual: clonal | Chihuahua, Coahuila | 3 | [4,38,56,59] | ||

| Agave scaposa Gentry | Maguey de Macho | Used for construction, food, living fence | Leptonycteris sp. | Bombus, hummingbirds | Sexual: pollination asexual: clonal | Puebla, Oaxaca | 2 | [4,38] | |

| Agave sebastiana Greene | ornament | Asexual: clonal | Baja California Sur | 5 | [4,38,47] | ||||

| Agave seemanniana Jacobi | Biliaa, Maguey chato | Mezcal production, food | Sexual: seeds | Oaxaca, Chiapas, Nicaragua | 5 | [4,38,40] | |||

| Agave shawii Engelm. | Amal | Ornament, food, distilled beverage production | Hummingbirds Leptonycteris, Bombus | Sexual: seeds asexual: clonal | Baja California, Southwest EU | 3 | [38,40,44,47] | ||

| Agave shrevei Gentry | Lechuguilla (Sonora), Ceniza, Lechuguilla ceniza, Mezcal blanco | Mezcal production, mead production, food | Sonora | 6 | [4,38,39,40,71] | ||||

| Agave sisalana Perrine | Henequén, Henequén verde, Maguey tuxtleco, Sisal | Fiber source, ornament | Asexual: clonal bulbils | Yucatán, Chiapas | 3 | [4,38,40,55] | |||

| Agave sobria Brandegee | Lechuguilla, Mezcal pardo | Mezcal production, food, ornament | Sexual: seeds asexual: clonal | Baja California Sur | 5 | [38,40,44,46,47] | |||

| Agave stringens Trel. | Jalisco | 4 | [4,38,45] | ||||||

| Agave tequilana F. A. C. Weber | Azul (San Luis Potosí, Jalisco), Chato (Michoacán), Tequila, Agave tequilero, Bermejo, Mano larga, Pata de mula, Chino azul, Chino bermejo | Tequila production, Food, fiber source, ornament, soap production | Asexual: clonal Sexual: pollination (minimum) | Jalisco | 3 | [4,38,39,40,41,55] | |||

| Agave turneri R. H. Webb and Salazar-Ceseña | Asexual: clonal | Baja California | EN | 5 | [34,38,47] | ||||

| Agave valencianaCházaro and A. Vázquez | Relisero (Jalisco) | Mezcal production, raicilla production, ornament | Sexual: seeds | Jalisco | CR | 8 | [34,39,40,72] | ||

| Agave vivipara L. | Lechuguilla | Food, mead production, fiber source, distilled beverage production | VU | 5 | [34,38,40] | ||||

| Agave vizcainoensis Gentry | Maguey de El Vizcaíno | ornament | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae | Asexual: clonal Sexual: pollination | Baja California Sur | 6 | [38,47,49,50] | ||

| Agave weberi J. F. Cels ex J. Poiss. | Maguey mezcalero, Maguey verde | Mezcal production, pulque production, ornament, fiber source | Asexual: clonal Sexual: pollination, seeds | Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas | 3 | [4,13,38,40] | |||

| Agave wocomahi Gentry | Maguey verde, Ojcome | Mezcal production, food, fiber source, mead production | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae | Sexual: pollination, seeds | Sonora, Durango, Chihuahua, Jalisco | 3 | [4,38,40] | ||

| Agave x glomeruliflora (Engelm.) A. Berger | Durango, Coahuila | 2 | [38,73] | ||||||

| Agave zebra Gentry | Áamxw, Káokt’ | Ornament, mezcal production, food | Sexual: seeds Asexual: bulbils | Sonora | VU | 6 | [34,38,40,44,74] |

* Distribution both in Italics and Bold means the species is endemic from that state.

Table 2.

Species of the subgenus Littaea with a summary of specific data according to their conservation status and biological environment.

Table 2.

Species of the subgenus Littaea with a summary of specific data according to their conservation status and biological environment.

| Species | Common Names | Uses | Pollinator | Floral Visitor | Reproduction | Distribution | IUCN Red List Category | Importance Score | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agave albomarginata Gentry | Maguey de márgenes claros | Ornament | Asexual: clonal | Coahuila, Chihuahua, Nuevo León, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas | EN | 5 | [4,34,38,40,48] | ||

| Agave albopilosa I. Cabral, Villareal and A. E. Estrada | Maguey viejito | Fiber source, ornament | Sierra Madre Oriental (exact location not given for protection) | CR | 9 | [34,38,40,75] | |||

| Agave angustiarum Trel. | Lechuguilla suave, Maguey de ixtle, Cacaya | Fiber source, food | Guerrero, Michoacán, Morelos, Oaxaca, Puebla | 4 | [38,48,76] | ||||

| Agave arizonica Gentry and J. H. Weber | Ornament | Asexual: clonal | Southwest EU (Arizona) | 5 | [4,38] | ||||

| Agave arcedianoensisCházaro, O. M. Valencia and A. Vázquez | Maguey de Arcediano | Ornament | Jalisco | VU | 7 | [34,38,48,61] | |||

| Agave attenuata Salm-Dyck | Maguey del Dragón | Ornament | Asexual: clonal | Guerrero, Jalisco, Colima, Michoacán, Nayarit, Sinaloa, Durango | 3 | [4,38,77] | |||

| Agave bakeri H. Ross | Ornament | Asexual: clonal Sexual: seeds | 3 | [4,38] | |||||

| Agave bracteosa S. Watson ex Engelm. | Maguey araña | Ornament, fiber source | Asexual: clonal | Coahuila | 7 | [4,38,40,49,50] | |||

| Agave calciphila G. D. Starr | Oaxaca | 4 | [38,78] | ||||||

| Agave celsii Hook. | Maguey comezonudo, Maguey de Peña | Medical use | Bombus, Leptonycteris, hummingbirds Sphingidae | Hidalgo, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas | 3 | [38,79] | |||

| Agave chazaroiA. Vázquez and O. M. Valencia | Ornament | Jalisco | VU | 7 | [34,38,76,77] | ||||

| Agave chiapensis Jacobi | Maguey Chamula | Ornament, food | Chiapas, Oaxaca | VU | 8 | [4,34,38,40,49,50] | |||

| Agave chrysoglossa I. M. Johnst. | Hasot, Amole | Ornament, local use for clothes washing, food | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, hummingbirds | Insects, hummingbirds | Sexual: pollination, seeds Asexual: clonal | Sonora | 4 | [4,38,40,44] | |

| Agave colimana Gentry | Maguey de Colima | Ornament | Colima, Jalisco, Nayarit | 4 | [4,38,48] | ||||

| Agave convallis Trel. | Jabalí (Oaxaca), Maguey Escobeta | Distilled beverage production | Oaxaca | VU | 7 | [34,38,39,48,67,80] | |||

| Agave dasyliriodes Jacobi and C. D. Bouche | Maguey intrépido | Ornament | Sexual: Seeds | Morelos | EN | 9 | [4,34,38,48,49,50] | ||

| Agave difformis A. Berger | Lechuguilla | Ornament, fiber source, soap | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Leptonycteris nivalis, Choeronycteris mexicana | Apis mellifera, Lasioglossum lasioglassum, Bombus, Centris, Polistinae, Agrius cingulatus, Pachylia ficus, Sphinx lugens, Erinnyis ello | Sexual: pollination Asexual: clonal | San Luis Potosi, Hidalgo | 2 | [4,38,81] | |

| Agave doctorensis L. Hern. and Magallán | Querétaro | CR | 7 | [34,38,82] | |||||

| Agave ellemeetiana Jacobi | Asexual: clonal Sexual: seeds | Veracruz, Oaxaca | 1 | [4,38,83] | |||||

| Agave felgeri Gentry | Food | Asexual: clonal | Sonora | VU | 8 | [4,38,40,44] | |||

| Agave filifera Salm-Dyck | Amole, Maguey de maceta | Pulque production, fiber source | Asexual: clonal Sexual: pollination | Hidalgo, Morelos | 3 | [4,13,38,40] | |||

| Agave garcia-mendozae Galván and Hern. | Ornament, fiber source | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Leptonycteris nivalis, Choeronycteris mexicana | Apis mellifera, Agrius cingulatus, Pachylia ficus, Sphinx lugens, Erinnyis ello | Sexual: pollination | Hidalgo | VU | 5 | [34,38,81] | |

| Agave garciaruizii A. Vázquez, Hern.-Vera and Padilla-Lepe | Asexual: clonal | Jalisco, Michoacán | 1 | [38,76] | |||||

| Agave geminiflora (Tagl.) Ker Gawl. | Palmilla | Ornament, fiber source | Hummingbirds | Sexual: pollination | Jalisco, Nayarit | VU | 4 | [4,34,38,40] | |

| Agave ghiesbreghtii Lem. ex Jacobi | Living fence | Asexual: clonal | Oaxaca, Puebla | 3 | [4,38] | ||||

| Agave glomeruliflora (Engelm.) A. Berger | Ornament | Sexual: seeds | Coahuila | 3 | [4,38] | ||||

| Agave gracielae Galvan and Zamudio | Food, ornament | Querétaro, San Luis Potosí | 4 | [38,84] | |||||

| Agave guiengola Gentry | Maguey plateado | Ornament | Asexual: clonal Sexual: seeds | Oaxaca | EN | 9 | [4,34,38,48,49,50] | ||

| Agave gypsicola García-Mend. and D. Sandoval | Maguey blanco (xavi kuiji) | Food, living fence | Oaxaca | 6 | [45,63] | ||||

| Agave horridaLem. ex Jacobi | Maguey bueno | Ornament, food, fiber source, distilled beverage production | Leptonycteris nivalis Choeronycteris mexicana | Tegeticula, Apis mellifera | Sexual: pollination Seeds | Morelos | 4 | [4,38,40,59,85] | |

| Agave impressa Gentry | Maguey Masparrillo | Medical use | Asexual: clonal | Sinaloa, Nayarit | EN | 9 | [4,34,38,49,50,61] | ||

| Agave jimenoi Cházaro and A. Vázquez | Veracruz | 4 | [38,86] | ||||||

| Agave kavandivi García-Mend. and C. Chávez | Food | Oaxaca | CR | 9 | [34,38,87] | ||||

| Agave kerchovei Lem. | Cacalla, Rabo de León | Food, fiber source, mead production, distilled beverage production | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae | Sexual: pollination | Puebla, Oaxaca | VU | 4 | [4,34,38,40,61] | |

| Agave lechuguilla Torr. | Amole, Lechuguilla, Istle, Ixtle | Fiber source | Hyles lineata, Xylocopa californica, Bombus pennsylvanicus, Eugenes fulgens, Calothorax lucifer, Archilochus alexandri, Selasphorus sp. | Apis mellifera, Selasphorus sp., vespidae, small bees | Asexual: clonal Sexual: pollination | Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Texas, Nuevo Mexico | 2 | [4,30,38,40,88] | |

| Agave lophantha Schiede | Maguey Estoquillo | Ornament | South EU (Texas), Chihuahua, Veracruz | 4 | [4,38] | ||||

| Agave manantlanicola Cuevas and Santana-Michel | Asexual: clonal | Jalisco | EN | 5 | [34,38,77] | ||||

| Agave maria-patriciae * Cházaro and Arzaba | Veracruz | 4 | [38,89] | ||||||

| Agave megalodonta * García-Mend. and D. Sandoval | Maguey espumoso | Occasional mezcal production | Oaxaca, Puebla, Guerrero | NT | 4 | [63] | |||

| Agave mitis Mart. | Maguey de Peña | Food, fiber source | Chiroptera, Bombus, Sphingidae, hummingbirds | Guanajuato, Coahuila, Puebla | 3 | [38,40,90] | |||

| Agave montium-sancticaroli García-Mend. | Jarcia | Mezcal production, food | Asexual: clonal | Tamaulipas | CR | 8 | [34,38,40,73] | ||

| Agave multifilifera Gentry | Chahuí | Ornament, fiber source, food, mead production, distilled beverage production | Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Nayarit, Sinaloa | 4 | [4,38,40] | ||||

| Agave muxii * Zamudio and G. Aguilar-Gutiérrez | Asexual: clonal | Querétaro, San Luis Potosí | 1 | [91] | |||||

| Agave nizandensis Cutak | Maguey de Nizanda | Ornament | Oaxaca | CR | 12 | [4,34,38,49,50] | |||

| Agave nussaviorum García-Mend. | Maguey Papalometl | Food, medical use, construction material, forage, distilled beverage production | Oaxaca | 6 | [38,40,69] | ||||

| Agave obscura Schiede ex Schltdl. | Lechuguilla Bronca | Ornament | Asexual: clonal | Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, Veracruz | 3 | [4,55] | |||

| Agave ocahui Gentry | Amolillo | Ornament, fiber source | Sexual: pollination seeds | Sonora | NT | 5 | [4,34,38,40] | ||

| Agave oteroi * G. D. Starr and T. J. Davis | Oaxaca, Puebla | 2 | [38,92] | ||||||

| Agave ornithobroma Gentry | Maguey Pajarito | Fiber source | Psitaciformes | Asexual: clonal | Sinaloa, Nayarit | VU | 5 | [4,34,38,49,50] | |

| Agave parviflora Torr. | Tauta (Sonora) | Ornament, food | Bombus sonorus, Xylocopa | Sexual: pollination Asexual: clonal | Chihuahua, Sonora, Southwest EU, Argentina | 5 | [4,30,38,39,40,49,50,81,93] | ||

| Agave peacockii Croucher | Amol, Lechuguilla, Maguey de Ixtle, Maguey fibroso | Fiber source, food, mead production, distilled beverage production | Asexual: clonal | Hidalgo, Puebla, Oaxaca | VU | 5 | [4,34,38,40,49,50] | ||

| Agave pedunculifera Trel. ex Standll. | Lechuguilla | Ornament | Asexual: clonal | Sinaloa, Jalisco, Nayarit, Colima, Michoacán, Guerrero | 3 | [4,38] | |||

| Agave pelona Gentry | Bacanora, Mezcal pelón | Food, distilled beverage production, ornament, fiber source | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae | Sexual: pollination | Sonora | CR | 8 | [4,34,38,40,44,78] | |

| Agave pendula Schnittsp. | Ornament | Asexual: clonal | Veracruz, Chiapas, Oaxaca | 3 | [4,38,48] | ||||

| Agave petrophila A. García-Mend. and E. Martínez | Ornament | Oaxaca, Guerrero | EN | 6 | [34,38,84] | ||||

| Agave polianthiflora Gentry | Chahuí | Ornament, food, mead production | Asexual: clonal | Sonora, Chihuahua | 5 | [4,38,40,49,50] | |||

| Agave polyacantha Haw. | Tamaulipas, Veracruz | 2 | [4,38] | ||||||

| Agave potrerana Trel. | Ornament | Coahuila, Chihuahua | 4 | [4,38] | |||||

| Agave quiotepecensis García-Mend. and S. Franco | Agave Rabo de León | Fiber source, food, forage | Oaxaca | NT | 6 | [63,78] | |||

| Agave rzedowskiana P. Carrillo, Vega and R. Delgad. | Sinaloa, Jalisco | 2 | [38,94] | ||||||

| Agave schidigera Lem. | O’r, Lechuguilla Mansa | Fiber source | Chihuahua, Jalisco, Zacatecas, Sinaloa, Durango, Aguascalientes, Guerrero, San Luis Potosí, Michoacán | 4 | [4,38,40] | ||||

| Agave schottii Engelm. | Icapánim, Amole | Leaves used as clothing soap, food, mead production | Bombus, Xylocopa, Leptonycteris | Hummingbirds, Xylocopa, Apis | Sexual: pollination Asexual: clonal | Northwest Chihuahua, Sonora, Southwest and South EU (Arizona and Nuevo Mexico) | 2 | [4,38,40,44,81,93] | |

| Agave striata Zucc. | Junquillo, Estoquillo, Maguey espadín, Palmita, Peinecillo | Ornament, fiber source, mead production | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, Leptonycteris nivalis, Choeronycteris mexicana | Apis mellifera, Lasioglossum lasioglassum, Bombus, Centris, Polistinae, Eugenes fulgens, Cynantus latirostris, Agrius cingulatus, Pachylia ficus, Sphinx lugens, Erinnyis ello | Sexual: pollination Asexual: clonal | Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Queretaro, Puebla | 2 | [4,30,38,40,81] | |

| Agave stricta Salm-Dyck | Pelo de ángel | Ornament, fiber source, food | Puebla, Oaxaca | 4 | [4,38,40] | ||||

| Agave tenuifolia Zamudio and E. Sánchez | Maguey de la Sierra Madre Oriental | Querétaro, Tamaulipas, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí | 2 | [38,95] | |||||

| Agave titanota Gentry | Cachitún | Ornament, distilled beverage production | Sexual: seeds | Oaxaca | EN | 8 | [4,34,38,40,49,50] | ||

| Agave triangularis Jacobi | Cacalla, Maguey tunecho | Ornament, food, fiber source | Asexual: clonal | Puebla, Oaxaca | VU | 4 | [4,34,38,40] | ||

| Agave univittata Haw. | Estoquillo, Lechuguilla (Sonora), Mezortillo | Distilled beverage production, fiber source | 4 | [4,38,39,40] | |||||

| Agave vazquezgarciae Cházaro and J. A. Lomelí | Food | Jalisco | 6 | [38,77,96] | |||||

| Agave victoriae-reginae (complex) T. Moore | Noa | Food, Fiber source, distilled beverage production | Asexual: clonal | Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, Durango | 6 | [4,38,40,49,50,55,97] | |||

| Agave victoriae-reginae (complex) | Maguey del Rey Fernando | Asexual: clonal | Coahuila | CR | 6 | [34,38,97] | |||

| Agave nickelsiae Rol.-Gross | |||||||||

| Agave victoriae-reginae (complex) | Ornament | Sexual: seeds Asexual: rhizomes | Durango | CR | 8 | [34,38,97] | |||

| Agave pintillaS. González, M. González and L. Reséndiz | |||||||||

| Agave vilmoriniana A. Berger | Ahué, Amole | Ornament, mead production, food, fiber source | Apis, Leptonycteris, Hummingbirds | Asexual: clonal bulbils Sexual: seeds | Sonora, Sinaloa, Durango, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, Southwest EU | 3 | [4,38,40,44] | ||

| Agave warelliana De Smet ex T. Moore and Mast. | Guatemala, Chiapas | EN | 4 | [4,34,38,45] | |||||

| Agave wendtii Cházaro | Veracruz | EN | 6 | [34,38,48] | |||||

| Agave xylonacantha Salm-Dyck | Kuat’ ma’ ye | Food, fiber source | Bombus, Leptonycteris, hummingbirds, Sphingidae, Choeronycteris mexicana | Sexual: pollination, seeds | Hidalgo, Guanajuato, Querétaro, Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí, Nuevo León | 3 | [4,38,40,59] | ||

| Agave yuccifolia DC | Ornament | Hidalgo | 4 | [4,38] |

* Distribution both in Italics and Bold means the species is endemic from that state.

Table 3 is the criteria and corresponding weight, or score, of each species used to create Table 4 where the species with the highest total importance scores were placed under three possible categories mentioned below. The higher the score of the parameters in Table 3, the higher the risk of extinction for the species, therefore those species require more attention, although precautionary measures should also be taken with the rest of the species.

Table 3.

Weighted score criteria regarding the data collected from the Agave species.

Table 4.

Species of subgenus Agave and Littaea under the established categories subjected to their conservation status and biological environment.

The species with the greatest importance score were arranged by subgenera and separated into three categories as follows: 1. Severely endangered: those species facing the possibility of extinction and that should be subjected to an urgent rescue and recovery program, considering the possibility of stopping harvest from the wild altogether. 2. High risk of extinction: these species need a recovery program and their harvest should be subjected to a strong conservation program. 3. Threatened species: management and recovery plans must be prepared and implemented for their harvest.

In order to evaluate the influence of score criteria in the Agave species, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed for each subgenus with the package FactoMineR [98], with the variables and categories used for the Importance score reported in Table 3.

3. Results and Discussion

The species distribution for the subgenera Littaea and Agave by state of Mexico are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. It is noteworthy that there are no records in Baja California or Yucatán for Littaea, and for Agave there are only three reported species in Yucatán, while for both subgenera, there are no published records for Quintana Roo, Campeche and Tabasco, which can be due to a lack of sampling in these areas. In Littaea the highest richness occurs in the southern state of Oaxaca, while for Agave also Oaxaca is the richest state, along with Sonora and Chihuahua in the northwestern part of the country. Both subgenera have lower numbers of species in the center of the country.

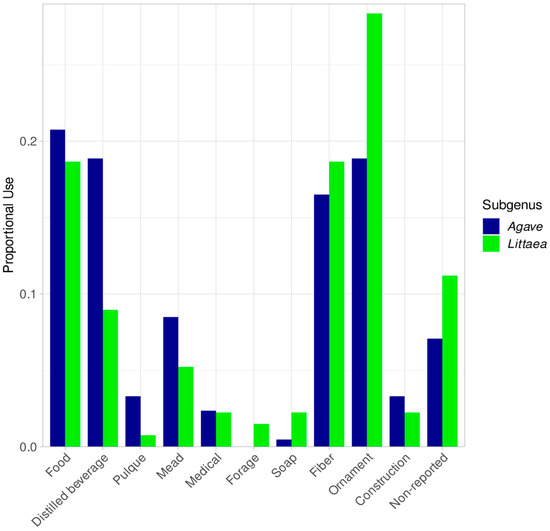

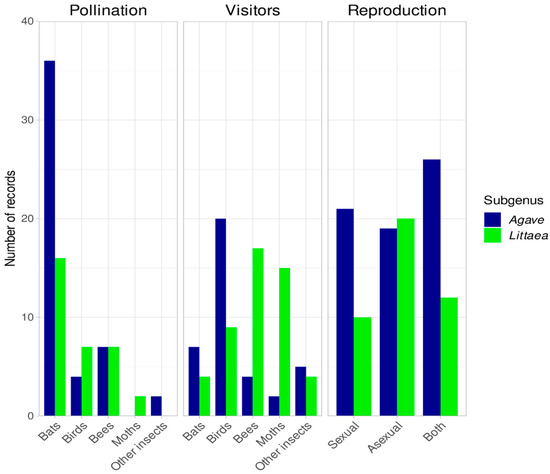

In both subgenera, the proportion of plants used for food is similar (Littaea 18.6% and Agave 20.7%, Figure 3), while Agave species are much more used for making distilled beverages (mainly mezcal and tequila) (Littaea 8.9% and Agave 18.8 %). The better-known species used for the production of distilled beverages were not considered at high risk, due to the proportionally greater knowledge available, although many of them might be endangered because of the lack of proper production management. For instance, these popular Agaves are now cultivated in massive monocultures, while preventing any sexual reproduction, and thus their genetic diversity is rapidly declining, such is the case of A. tequilana [6,18].

Figure 3.

Proportional uses for Littaea and Agave subgenus.

The use for fibers is proportionally similar for Littaea and Agave (18.6% vs. 16.5%, respectively, Figure 3), compared to the use of ornamentals, where Littaea has a higher use (28.3% vs. 18.8%, respectively, Figure 3). Species used for fiber, such as A. parrasana, A. albopilosa, A. pelona and A. pintilla were categorized at a high risk of extinction, while A. lurida and A. nizandensis are considered severely endangered and used as ornamentals. It is outstanding that in both subgenera the vast majority of the reported species have some kind of use (Litteae 88.9% and Agave 93.03%, Figure 3).

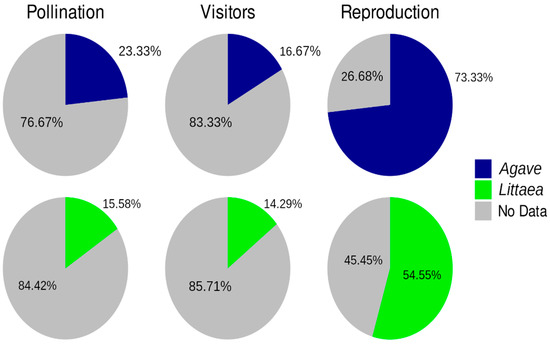

It is important to note that most of the species included in Table 4, which are in need of specific conservation efforts, are used for fiber, ornamentals or have no known uses. There is very little information regarding pollinators and visitors in both subgenera for most species (more than 75%, Figure 4). Obviously, this is important information necessary to develop adequate conservation and management strategies. Bat pollination records are much greater in Agave than in Littaea (Figure 5). For visitors, available information shows an important difference between subgenera (Figure 5), but more studies are needed to disentangle if these visitors are acting as true pollinators. There is ample information for the general type of reproduction in both subgenera (Figure 5), which may be due to the fact that as mentioned above, species from both subgenera are widely used, so there is an interest in having this information.

Figure 4.

Proportion of the information available concerning pollination, visitors and reproduction for Littaea and Agave subgenus. Grey areas represent the absence of information.

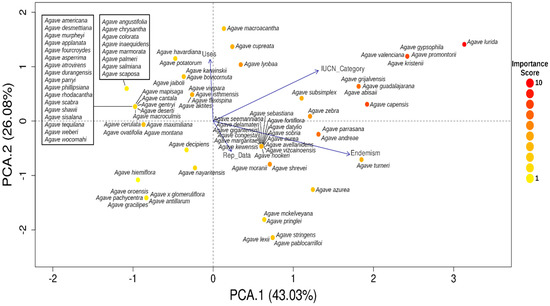

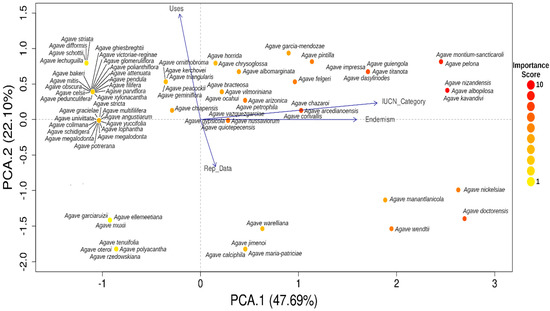

The PCA analyses of the different variables reported in Table 3 for both subgenera (Figure 6 and Figure 7) were divided into four quadrants:

Figure 6.

Principal Component Analysis of the Agave subgenus Agave using the IUCN category, uses, endemism, and reproductive data as variables (see Table 1 for details). Dot color represents the Importance Score obtained.

Figure 7.

Principal Component Analysis of the Agave subgenus Littaea using the IUCN category, uses, endemism, and reproductive data as variables (see Table 2 for details). Dot color represents the Importance Score obtained.

I. Species with higher importance scores are in Quadrant I. Many of these species are endemic and have many uses, so they can be considered species of main concern for conservation and management.

II. This quadrant contains endemic species with little use and with little or no reproductive information, which is mainly associated with a lack of interest, in contrast to species in quadrants I and III.

III. Species with many uses, so much more reproductive information is available, but a lower importance score than species in Quadrant I.

IV. Species that apparently have no use and are not endemic, but reproductive information is lacking for them.

Having an understanding of the status of each species of the genus Agave in Mexico is fundamental to species conservation and sustainable use, and to create awareness of the practices used nowadays on the utilization of the different species of the genus, averting the possible tragic outcome of extinction. Artisanal and industrial producers are invited to maintain or opt for biodiversity-friendly alternatives for the conservation of agaves, practicing sustainable methods in their practices with agaves. Suggested approaches include the use of species considered at low risk of extinction for the production of distilled beverages (for instance A. americana, A. duranguensis, A. karwinskii or A. macroacantha) or ecofriendly production methods for agaves and their pollinators, such as the Bat Friendly Tequila and Mezcal project [99] created by UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico) and the Tequila Interchange Project [19,100]. This project seeks to preserve genetic diversity, seed production and pollinator populations, including bats, by allowing 5% of the agaves in agave fields destined for production of distillates to flower and produce seeds.

Restricting the use of agave species that are at risk may not be an adequate method for the conservation of some species, except in the most critically endangered cases, given that many Mexicans depend on their production to survive [2] and such restrictions might trigger a wave of poaching plants from wild populations. The great potential of sustainable management practices to ensure the future of particular agave species such as the maguey papalote (A. cupreata) and its derivatives and products has already been demonstrated. By providing greater visibility to sustainable practices by the local farmers, knowledge exchange between producers and science and preserving ancestral traditional production practices, agaves clearly have a profitable, sustainable, environment-friendly, socially responsible, and economically viable future [101,102].

It is also important to mention that the taxonomy of the genus Agave has been a complicated task for scientists, given that the genus is one of the most species-rich in the plant kingdom, and therefore recent discoveries that indicate synonymies and cryptic species are constant events, resulting in ongoing changes and descriptions of new species (see [31]). We must emphasize that there is still a great amount of data to collect on recently described species along with their distributions, natural history, current uses and pollinators to fully understand their biology, potential as providers of services and products, and conservation needs [31]. This study is just the beginning of an effort to update the knowledge about the uses, information available, and conservation needs of Agave species, and we hope to continue to facilitate updates in the future.

Agaves are among the most ecologically and economically important plants of Mexico. From an economic perspective, the role of Agave in production of distilled beverages and fibers, their ornamental relevance, and rural uses as living fences and building materials are very important for the country. In particular, exports of tequila and mezcal are undergoing a huge upward trend. Tequila exports went from 209 million liters in 2018 [103] to 249.4 million liters in 2021 with a net value of $2.3 billion dollars [17]. Mezcal exports went from 2.7 million liters to 7.1 million liters only from 2016 to 2018, with a value of $53 million dollars [103,104,105]. People directly or indirectly involved in the production of mezcal and tequila depend on the income generated by these distilled beverages. Additionally, Mexicans throughout the country depend on agaves for different products such as handcrafts, baskets or ropes made from their fibers, their use in Mexican cuisine for many typical dishes, and the preparation of the pre-Hispanic fermented drink, pulque.

Agaves are emblematic plants for Mexico and have been represented in codex, archeological vestiges and cultural traditions since pre-Hispanic times, being nowadays an extensive source of income and everyday life uses. We must prevent the extinction of agave species due to greedy, industrialized production and cultivation practices. Respect for traditional procedures, clear recognition and incorporation of traditional indigenous knowledge and preserving, creating, and implementing the best sustainable production practices is absolutely crucial for the future of agaves and their pollinators. Local communities demand this with reason, Mexico deserves this, and the world should expect nothing less. The future of Agave and its pollinators should be one of appreciation, respect, and responsible consumption of agave products, solidly anchored in environmental sustainability, social justice, and economic viability.

4. Conclusions

Our analysis highlights the great diversity of species of the genus Agave in Mexico, the intense level of use that some species are undergoing, the species-specific extinction risk level, and the lack of knowledge about most species. In the process of constructing this diagnostic analysis, it was clear that most of the available information for most species is scarce given their usefulness and distribution.

For the agaves used in mezcal production, we believe that the most convenient solution is to opt for strict sustainable management practices and favorable reproduction methods, while avoiding monoculture procedures that could affect genetic variability, and reduce or avoid the use of pesticides that affects pollinators thus affecting gene flow and connectivity between species. It is important to favor the natural sexual reproduction of the species, promoting natural pollination and protecting their pollinators. Traditional practices should be encouraged for the management of agaves, recognizing monocultures and high industrialization processes as inadequate and only happening under highly controlled conditions, ensuring the future of biodiversity and emphasizing the knowledge of local, traditional producers.

Author Contributions

C.A.-M. wrote the first draft of the paper and research. J.G.-P., L.E.E. and E.A.-P. analyzed data, made the figures, interpreted the patterns and wrote the related sections. O.J.-B., J.G.-P., K.Y.R.M., E.A.-P., L.E.E. and R.A.M. commented and complemented subsequent versions. R.A.M. conceptualized and directed the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by GIZ Mexico, the Whitley Fund for Nature, Arizona Game and Fish Department, the Tequila Interchange Project, and the Bat Friendly Tequila and Mezcal Program. OJ, JGP, KM, EAP, RM and LEE reserarch on Agave is funded by grant PAPIIT IG200122, UNAM to Luis E. Eguiarte and Rafael Lira, and project “Auge mezcalero y deudas de extinción: investigación interdisciplinaria hacia la sustentabilidad” granted to Alfonso Valiente Banuet by CONACyT-PRONACES, 319061-Sistemas socioecológicos. The page charges were paid with support of the operative budget of the Instituto de Ecología, UNAM assigned to LEE and RM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in the published literature as discussed in the article.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge and thank GIZ MX for providing financial support and encouragement for conducting this analysis and research paper. We also thank Claudia Moreno from Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico and Regina Sanchez from GIZ MX for providing technical and content support on the analysis and Pedro Jimenez for contributing specific agave information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- CONABIO (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad). Mezcales y Diversidad, 2nd ed.; CONABIO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mendoza, A.; Nieto-Sotelo, J.; Sánchez-Teyer, L.; Tapia, E.; Gómez-Leyva, J.; Tamayo-Ordoñez, M.C. Panorama del Aprovechamiento de los Agaves en Mexico. In AGARED—Red Temática Mexicana Aprovechamiento Integral Sustentable y Biotechnología de los Agaves; CONACYT, CIATEJ, AGARED: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2017; ISBN 978-607-97548-5-3. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mendoza, A.J. Los Agaves de Mexico. Rev. Cienc. 2007, 87, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, H.S. Agaves of Continental North America, 3rd ed.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, S.M.; Martin, J.A.; Simpson, J.; Abraham-Juarez, M.J.; Wang, Z.; Visel, A. De novo transcriptome assembly of drought tolerant CAM plants, Agave deserti and Agave tequilana. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colunga-GarcíaMarín, P.; Zizumbo-Villarreal, D.; Martínez-Torres, J. Tradiciones en el aprovechamiento de los agaves mexicanos: Una aportación a su protección legal y conservación biológica y cultural. In En lo Ancestral Hay Futuro: Del Tequila, los Mezcales y Otros Agaves; Colunga-García Marín, P., Eguiarte, L., Largu, A., Zizumbo-Villarreal, S.y.D., Eds.; CICY-CONACYT-CONABIO-INE: Mérida, Mexico, 2007; pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castetter, E.F.; Harvey, W.; Russell, A. The Early Utilization and Distribution of Agave in the American Southwest. University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository. 1938. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/es/occurrence/search?q=agave kewensis (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Álvarez-Ríos, G.; Pacheco-Torres, F.; Figueredo-Urbina, C.; Casas, A. Management, Morphological and Genetic Diversity of Domesticated Agaves in Michoacán, Mexico. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, R.; Jiménez, J.F.; Del Real, J.I.; Salcedo, E.; Zamora, J.F.; Íñiguez, G. Utilización de Subproductos de la Industria Tequilera. Parte 11. Compostaje de Bagazo de Agave Crudo y Biosólidos Provenientes de una Planta de Tratamiento de Vinazas Tequileras. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambie 2013, 29, 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Quiñones, P.; Rodríguez, A.; Negrete, L. Extracción de fibras de agave para elaborar papel y artesanías. Acta Univ. 2010, 20, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklu, T. Characterization of Physico-chemical, Thermal, and Mechanical Properties of Ethiopian Sisal Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 3825–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Cristóbal, N.; Martínez, J.L.; Medina-Morales, M.A.; Nava-Cruz, N.Y. Agave biotechnology: An overview. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Duarte, M.C.; García-Moya, E.; Suárez-Espinosa, J.; Luna-Cavazos, M.; Rodríguez-Acosta, M. Conocimiento tradicional, cultivo y aprovechamiento del maguey pulquero en los municipios de Puebla y Tlaxcala. Polibotánica 2018, 45, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlín, J.D.G. Pulque, la Bebida de los Dioses al Alcance de Todos. 2017. Available online: https://www.redinnovagro.in/casosexito/2017/Maguey_Corporativo_San_Isidro.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Chavez-Angeles, M.; Pérez, M.; Vázquez, L.; Sánchez, M.; Pérez-García, O.; Hernandez, O. David vs. Goliat: La conservación de los agaves pulqueros (Agave atrovirens, salmiana o americana), el combate a la pobreza y la competencia con la industria global de la cerveza en la Reserva de la Biósfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. In Proceedings of the Segundo Congreso Nacional Agave-Mezcal, Oaxaca, Mexico, September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro del Toro, G.J. El tequila para consumo nacional como una ventana de oportunidades para el pequeño productor agavero. Rev. Iberoam. Contad. Econ. Adm. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara Nacional de la Industria Tequilera (CNIT). Información Básica de la Industria Tequilera. 2021. Available online: https://www.tequileros.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/estadisticas.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Ceja-Ramírez, R.; González-Eguiarte, D.R.; Ruiz-Corral, J.A.; Rendón-Salcido, L.A.; Flores-Garnica, J.G. Detección de restricciones en la producción de agave azul (Agave tequilana Weber var. azul) mediante percepción remota. Terra Latinoam. 2017, 35, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Trejo-Salazar, R.E.; Eguiarte-Fruns, L.E.; Suro-Piñera, D.; Medellin, R.A. Save our bats, save our tequila: Industry and science join forces to help bats and agaves. Nat. Areas J. 2016, 36, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Justo, M.; García-Oropeza, L.; Barboza-Corona, J.E.; Parra-Negrete, L.A. El Agave tequilana Weber y la Produccion de Tequila. Acta Univ. 2001, 11, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Meza, P.; Mandujano-Bueno, A.; Paredes-Melesio, R.; Pons-Hernández, J.L. Diversidad genética del maguey (Agave spp.) en las sierras y llanuras del norte de Guanajuato. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2018, 9, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Solís-García, A.; Rivas-García, P.; Escamilla-Alvarado, C.; Rico-Martínez, R.; Bravo-Sánchez, M.; Botello-Álvarez, J. Methanol Production Kinetics during Agave Cooking for Mezcal Industry. Revista Mexicana De Ingeniería Química 2017, 16, 827–834. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=62053304012 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Eguiarte, L.E.; González-González, A. De genes y magueyes estudio y conservación de los recursos genéticos del tequila y el mezcal. Rev. Cienc. 2007, 87. Available online: http://rmiq.org/ojs311/index.php/rmiq/article/view/944 (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Klimova, A.; Ruiz Mondragón, K.Y.; Molina Freaner, F.; Aguirre-Planter, E.; Eguiarte, L.E. Genomic analyses of wild and cultivated bacanora agave (Agave angustifolia var. pacifica) reveal inbreeding, few signs of cul-tivation history and shallow population structure. Plants 2022, 11, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Coronado, M.L.; Acedo-Féliz, E.; Valenzuela-Quintanar, A.I. Industria del Bacanora y su Proceso de Elaboración. Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2007, 5, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Lugo, M.; García-Mendoza, A.; Simpson, J.; Solano, E.; Gil-Vega, K. Taxonomic implications of the morphological and genetic variation of cultivated and domesticated populations of the Agave angustifolia complex (Agavoideae, Asparagaceae) in Oaxaca, Mexico. Plant Syst. Evol. 2018, 304, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Toledo, D.; Vargas-Ponce, O.; Ascencio-Ramírez, S.; Valadez-Sandoval, L.M.; Pérez-Alquicira, J.; Morales-Saavedra, J.; Huerta-Galván, O.F. Morphological and Genetic Variation in Monocultures, Forestry Systems and Wild Populations of Agave maximiliana of Western Mexico: Implications for Its Conservation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguiarte, L.E.; Souza, V.; Silva-Montellano, A. Evolución de la familia Agavaceae: Filogenia, biología reproductiva y genética de poblaciones. Boletín Sociedad Botánica Mexico 2000, 66, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Valdez, L.I.; Vargas-Ponce, O.; Cabrera-Toledo, D.; Casas, A.; Cibrian-Jaramillo, A.; Cruz-Larios, L. Effects of traditional management for mescal production on the diversity and genetic structure of Agave potatorum (Asparagaceae) in central Mexico. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015, 63, 1255–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguiarte, L.E.; Jiménez-Barrón, O.A.; Aguirre-Planter, E.; Scheinvar, E.; Gámez, N.; Gasca-Pineda, J.; Castellanos-Morales, G.; Moreno-Letelier, A.; Souza, V. Evolutionary ecology of Agave: Distribution patterns, phylogeny, and coevolution (an homage to Howard S. Gentry). Am. J. Bot. 2021, 108, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguiarte, L.E.; Aguirre-Planter, E.; Aguirre, X.; Colín, R.; González, A.; Rocha, M.; Scheinvar, E.; Trejo, L.; Souza, V. From isozymes to genomics: Population genetics and conservation of Agave in Mexico. Bot. Rev. 2013, 79, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Vega, K.; Chavira, M.G.; de la Vega, O.M.; Simpson, J.; Vandemark, G. Analysis of genetic diversity in Agave tequilana var. azul using RAPD markers. Euphytics 2001, 119, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Comercio y Fomento Industrial. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-070-SCFI-1994. Bebidas Alcohólicas-Mezcal-Especificaciones; Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2020-2. 2020. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-García, J.; Muñiz-Castro, M.; Sahagún-Godínez, E.; Cházaro-Basáñez, M.; De Castro-Arce, E.; Nieves-Hernández, G.; Padilla-Lepe, J. Four New Species of Agave (Agavaceae) of the Marmoratae Group. Syst. Bot. 2013, 38, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colunga-GarcíaMarín, P. CONABIO. Base de Datos de Nombres Técnicos o de Uso Común en el Aprovechamiento de los Agaves en Mexico. Version 1.9. 2021. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/dataset/d9bceb64-0334-43e8-868e-72d4cd506ca1 (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- TodoMezcal 2012. Listado de Agaves por su Nombre Popular. Available online: http://www.todomezcal.com/AgavesTec/AgavesListadoPopular.html (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Colunga-GarcíaMarín, P.; Torres-García, I.; Casas, A.; Figueredo, C.; Rangel-Landa, S.; Lemus, A.; Vargas-Ponce, O.; Toledo, D.; Zizumbo-Villarreal, D.; Aguirre-Dugua, X.; et al. Los agaves y las prácticas mesoamericanas de aprovechamiento, manejo y domesticación. Domesticación Continente Americano 2017, 11, 273–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, H.; Peña, C.; Aguirre, J.; Reyes, J.; Sánchez, A.; Valle, S. Seed germination temperatures of eight Mexican Agave species with economic importance. Plant Species Biol. 2012, 27, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-García, I.; García-Mendoza, A.; Sandoval, D. Agave guadalajarana, Masparillo THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™. 2019. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/115629200/116353893 (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Lachenmeier, D.; Sohnius, E.; Attig, R.; López, M. Quantification of Selected Volatile Constituents and Anions in Mexican Agave Spirits (Tequila, Mezcal, Sotol, Bacanora). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3911–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Bowers, J.; Burgess, T. Sonoran Desert Plants: An Ecological Atlas; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- NaturaLista. Available online: https://www.naturalista.mx/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Webb, R.; Starr, G. The Real Agave gigantensis in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Cactus Succul. J. 2014, 86, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R. Gentry Revisited: The Agaves of Baja California, Mexico. Halsetonia 2015, 20, 64–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enciclovida. CONABIO. Available online: https://enciclovida.mx/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. Modificación del Anexo Normativo III, Lista de Especies en Riesgo de la Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección Ambiental-Especies Nativas de Mexico de Flora y Fauna Silvestres-Categorías de Riesgo y Especificaciones para su Inclusión, Exclusión o Cambio-Lista de Especies en Riesgo, Publicada el 30 de Diciembre de 2010. Diario Oficial de la Federación 14 Noviembre. 2019. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/profepa/documentos/norma-oficial-mexicana-nom-059-semarnat-2010 (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- SEMARNAT. Modificación del Anexo Normativo III, Lista de Especies en Riesgo de la Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección Ambiental-Especies Nativas de Mexico de Flora y Fauna Silvestres-Categorías de Riesgo y Especificaciones para su Inclusión, Exclusión o Cambio-Lista de Especies en Riesgo, Publicada el 30 de Diciembre de 2010. Diario Oficial de la Federación 14 Noviembre. 2019. Available online: http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5578808&fecha=14/11/2019 (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Parker, K.; Hamrick, J.; Hodgson, W.; Trapnell, D.; Parker, A.; Kuzoff, R. Genetic consequences of pre-Columbian cultivation for Agave murpheyi and A. delamateri (Agavaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2007, 94, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Quezada, A.; González-Chauvet, R.; Molina-Freaner, F.; Eguiarte, L. Genetic differentiation in the Agave deserti (Agavaceae) complex of the Sonoran desert. Heredity 2003, 90, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-García, I.; León, A. Aspectos de la Fenología, Visitantes Florales y Polinización de Agave inaequidens Koch ssp. Inaequidens (Agavaceae) en el Estado de Michoacán; Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo: Morelia, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, T.O. Foraging Ecology of the Long-Nosed Bat, Glossophaga Soricina, with Respect to Resource Availability. Ecol. Ecol. Soc. Am. 1984, 65, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monja-Mio, K.; Herrera-Alamillo, M.; Sánchez-Teyer, L.; Robert, M. Breeding Strategies to Improve Production of Agave (Agave spp.). In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Industrial and Food Crops; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Valdez, A.; Honeycutt, R.; Grant, W. Colony Dynamics of Leptonycteris nivalis (Mexican Long-Nosed Bat) Related to Flowering Agave in Northern Mexico. J. Mammal. 2004, 85, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, A.; Octavio-Aguilar, P.; Barrientos-Lozano, L.; Meerow, A.W. Effect of Elevation Strata on Morphological Variation of Two Agave Species with Different Niche Amplitude. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2019, 180, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Urbina, A.; Ventura-Canseco, L.M.C.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Abud-Archilla, M.; Peez-Farrera, M.A.; Dendooven, L.; Gutierrez-Miceli, F.A. Seed Germination and in vitro Propagation of Agave grijalvensis an Endemic Endangered Mexican Species. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2008, 7, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Burke, R.; Frey, J.; Ganguli, A.; Stoner, K. Species distribution modeling supports “nectar corridor” hypothesis for migratory nectarivorous bats and conservation of tropical dry forests. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 1399–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, A. Pollination Ecology of Agave palmeri in New Mexico, and Landscape Use of Leptonycteris nivalis in Relation to Agaves. 2012. Available online: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/31 (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Hernández-Ramírez, G.; Herrera, G. Allocation of endogenous nutrients for reproduction in the lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae ) in central Mexico. J. Mammal. 2016, 97, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- García-Morales, L.; García-Jiménez, J.; Iamonico, D. Agave lexii (Asparagaceae: Agavoideae), a New Species from Mexico. Novon 2019, 27, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mendoza, A.; Franco-Martínez, S.; Sandonval-Gutiérrez, D. Cuatro especies nuevas de Agave (Asparagaceae, Agavoideae) del sur de Mexico. Acta Bot. Mex. 2019, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, F.; Wilson, D. Leptonycteris yerbabuenae. Mamm. Species 2006, 797, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizaga, S.; Ezcurra, E.; Peters, E.; Arellano, F.; Vega, E. Pollination Ecology of Agave macroacantha (Agavaceae) in a Mexican Tropical Desert. I. Floral Biology and Pollination Mechanisms. Am. J. Bot. 2000, 87, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora-López, L.; Reyes-Agüero, A.; Flores-Flores, J.; Peña-Valdivia, C.; Aguirre-Rivera, R. Variación morfológica y humanización de la sección Salmianae del género Agave. Agrociencia 2011, 45, 1405–3195. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mendoza, A.; Sandoval, D.; Torres-García, I.; Casas, A.; González-Elizondo, M. Agave maximiliana, Lechuguilla 2019. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™. Available online: www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Hodgson, W.; Salywon, A.; Doelle, W. Hohokam Lost Crop Found: A New Agave (Agavaceae) Species Only Known from Large-scale pre-Columbian Agricultural Fields in Southern Arizona. Syst. Bot. 2018, 43, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mendoza, A. Revisión Taxonómica del complejo Agave potatorum Zucc. (Agavaceae): Nuevos Taxa y Neotipificación. Acta Bot. Mex. 2010, 91, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizumbo-Villarreal, D.; Colunga-García, P.; Vargas-Ponce, O.; Rosales-Adame, J.; Nieto-Olivares, R. Tecnología agrícola tradicional en la producción de vino mezcal (mezcal y tequila) en el sur de Jalisco, Mexico. Rev. Geogr. Agric. 2009, 42, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, B.; Valente, A.; Paz, J. A new steroidal saponin from Agave shrevei. Nat. Prod. Res. 2006, 20, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cházaro-Basáñez, M.; Vázquez-García, J.; Vargas-Rodriguez, Y. Agave valenciana (Agavaceae), A Gigantic New Species from Jalisco, Mexico. Novon 2005, 15, 525–530. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mendoza, A.; Jacques-Hernandez, C.; Salazar-Bravo, A. A new species of Agave, subgenus Littaea (Agavaceae) of Tamaulipas, Mexico. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas 2007, 1, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, G.; Kemble, B.; Nixon, R. Agave pelona and Agave zebra in the Sierra El Viejo. Cactus Succul. J. 2008, 80, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, I.; Villarreal-Quintanilla, J.A.; Estrada, E. Agave albopilosa (Agavaceae, subgénero Littaea, grupo Striatae), una especie nueva de la Sierra Madre Oriental en el noeste de Mexico. Acta Bot. Mex. 2007, 80, 51–57. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/574/57408005.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vera, G.; Vázquez-García, J.; Padilla-Lepe, J.; Nieves-Hernández, G. Agave garciaruizii (Asparagaceae) a new species from the Chorros del Varal State Reserve in western Mexico. Phytotaxa 2019, 422, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas Guzmán, R.; Santana-Michel, F.; Balcazar-Medina, O. Agave manantlanicola (Agavaceae), a new species from western Mexico. Brittonia 2012, 64, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]