Ethnobotanical History: Duckweeds in Different Civilizations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Duckweeds in Ancient Cultures

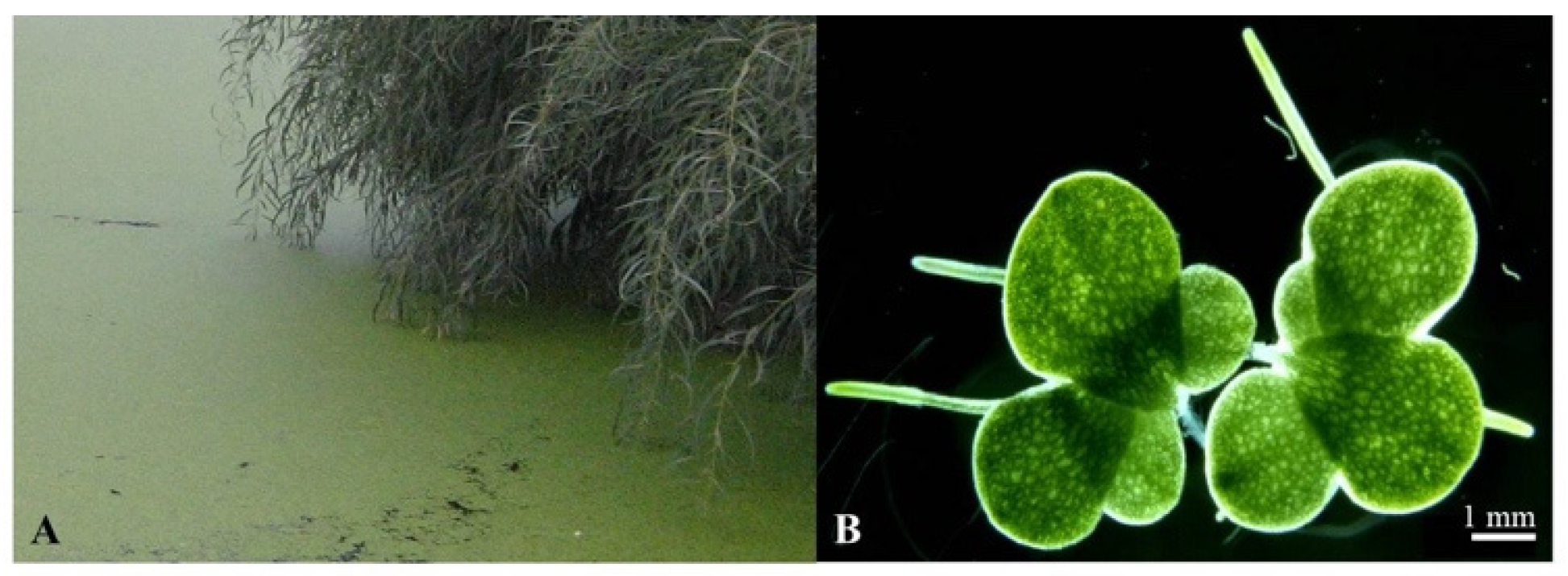

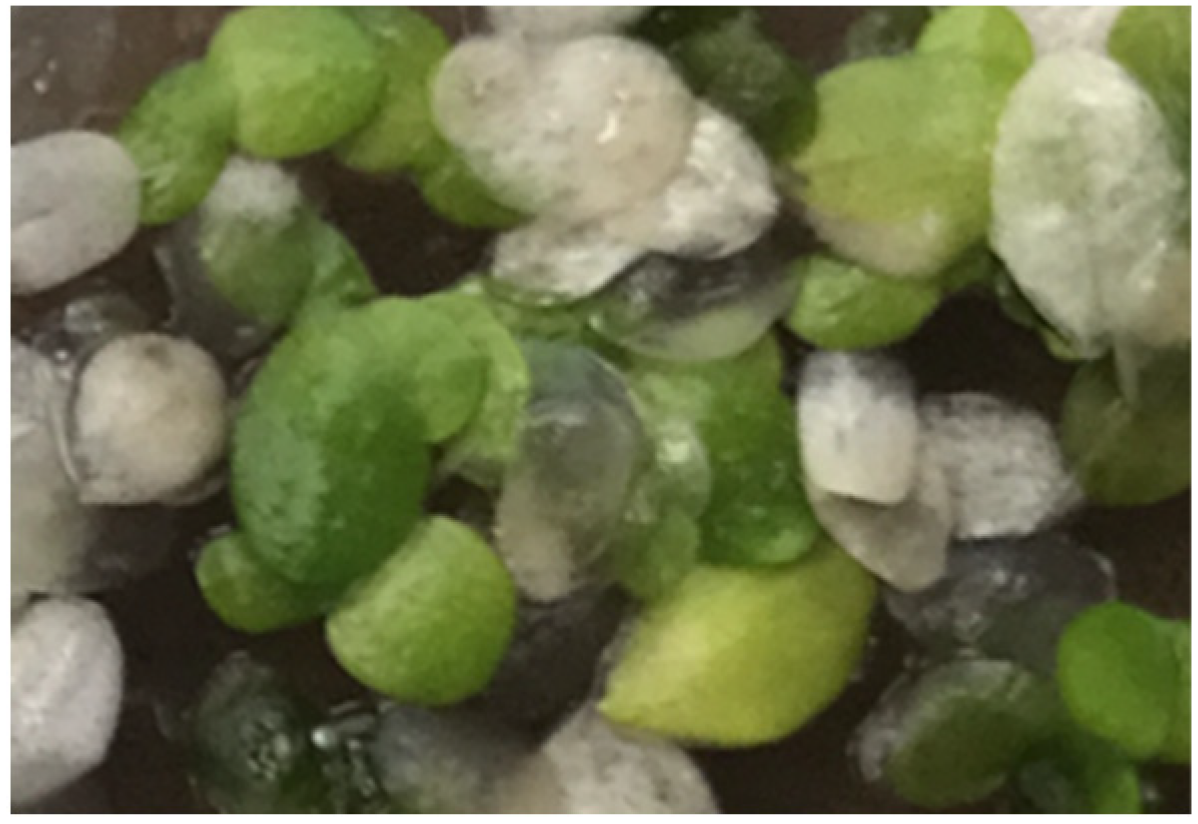

Duckweed’s Habitat

Duckweed in Ancient Greece: Theophrastus’ Enquiry into Plants

“[10.2] Now in the lake near Orchomenos grow the following trees and woody plants: willow(,) goat-willow(,) water-lily reeds [both that used for making pipes and the other kind](,) galingale(,) phleos(,) bulrush; and also ‘moon-flower’(,) duckweed and the plant called marestail: as for the plant called water-chickweed the greater part of it grows under water.”

“[10.3] Now of these most are familiar: the goat-willow(,) water-lily(,) ‘moon-flower’(,) duckweed and marestail probably grow also elsewhere, but are called by different names. Of these we must speak. The goat-willow is of shrubby habit and like the chaste-tree: its leaf resembles that leaf in shape, but it is soft like that of the apple, and downy. The bloom is like that of the abele, but smaller, and it bears no fruit. It grows chiefly on the floating islands; [for here too there are floating islands as in the marshes of Egypt, in Thesprotia, and in other lakes]...”

“[10.5] Of the plants of the lake they say that water-lily(,) sedge(,) and phleos bear fruit, and that of the sedge is black, and in size like that of the water-lily. The fruit of phleos is what is called the ‘plume,’ and it is used as a soap-powder... Duckweed(,) ‘moon-flower’ and marestail require further investigation.”

and in English,“... ad haec menififlora, icma, & quod ipnum appellant. Qnod enim lemna vocatur, altius mergitur in aqua.”[15]

However, when compared to Hort’s translation“... menififlora, icma, and what they call ipnum. For what is called the lemna is immersed deeper in water.”(translated from the Latin by Susanne Kochs).

it becomes evident that Theophrastus did not coin the term “lemna” specifically for duckweed (which, characteristically, floats on the water’s surface) but rather as a general term for ‘water plants’ (in this case, one that “is immersed”, or “grows”, under water).“... ‘moon-flower’(,) duckweed and the plant called marestail: as for the plant called water-chickweed the greater part of it grows under water.”[10]

3. Medicinal Applications Involving Duckweeds in Ancient and Classical Sources

3.1. Duckweed in the Roman Empire: Dioscorides’ Materia Medica

Phakos epi ton telmaton (Adapted from a translation of the Greek by Susanne Kochs.)

Lens on swamps/stagnant water bodies: it is found on stagnant water; it is a moss with similarity to a lens; with its power it is cooling; against all phlegmon [diffuse inflammation], erisypelas [bacterial inflammation of the skin] and podagral [foot gout] it helps when it is applied alone or together with barley. It also seals hernias in children.

“It is also called wild lens, or epipteron, the Romans call it viperalis, and some, iceosmigdonos.”

3.2. The Divine Farmer’s Chinese Materia Medica Classic

“Shui Ping (water weed) is acrid and cold. It mainly treats fulminant heat and generalized itching, precipitates water qi, [helps] get over wine, promotes the growth of the beard and [head] hair, and quenches wasting thirst. Protracted taking may make the body light. Its other name is Shui Hua [water flower]. It grows in pools and swamps.”(adapted from [12]; found just before comment 187)

3.3. Duckweeds in Medieval Christian Europe

4. Duckweeds in Ancient Religious Rituals

4.1. Duckweed in the Maya Civilization: Ritual of the Bacabs

4.2. Duckweed in the Babylonian Talmud

“With what may we light [the Sabbath lamp], and with what may we not light it? We may not light it with a wick made of cedar-bast (lechesh), uncombed flax (chosen), floss-silk (chalach), or with a wick of willow-fiber (iddan), desert weed (petilat ha-midbar), or duckweed (yaroka on the face of the water) [since such wicks burn unevenly]. It may not be lighted with pitch (zefet), liquid wax (shaava), castor oil (shemen kik), nor with oil that must be burned and destroyed (shemen s’raifa), or with tail fat (alyah), nor with tallow (chailev). Nahum of Media says: We may use melted tallow (chailev mevushal). The sages, however, say: It is immaterial whether or not it is melted, it must not be used for the Sabbath lamp.”(Mishna, Treatise Shabbat, Ch. 2; adapted from [38]).

“This yaroka, what is its nature? If you say that it is the yaroka on top of the narrow channels [where water gathers and there is greenery on top], it crumbles [and a wick cannot be made from it]. However, Rav Pappa said that it is referring to the yaroka that accumulates on a ship [as greenery (at the water line) when a ship is stationary].” (Gemara, Tractate Shabbat, p. 20b; Translated by M.E., also the following passages. In brackets, comments by Rashi (1040–1105 CE), a leading interpreter of the Gemara).

thus implying a stagnant, freshwater site.“... Yaroka on the surface of the water that remains on the ground without moving and is not flowing...”,[40]

“...and the Sanhedrin was exiled... to Yavne, and from Yavne to Usha…and from Usha to Shefaram, and from Shefaram to Bet She’arim, and from Bet She’arim to Tzippori, and from Tzippori to Tiberias”.(Gemara, tractate Rosh Hashana, 31a)

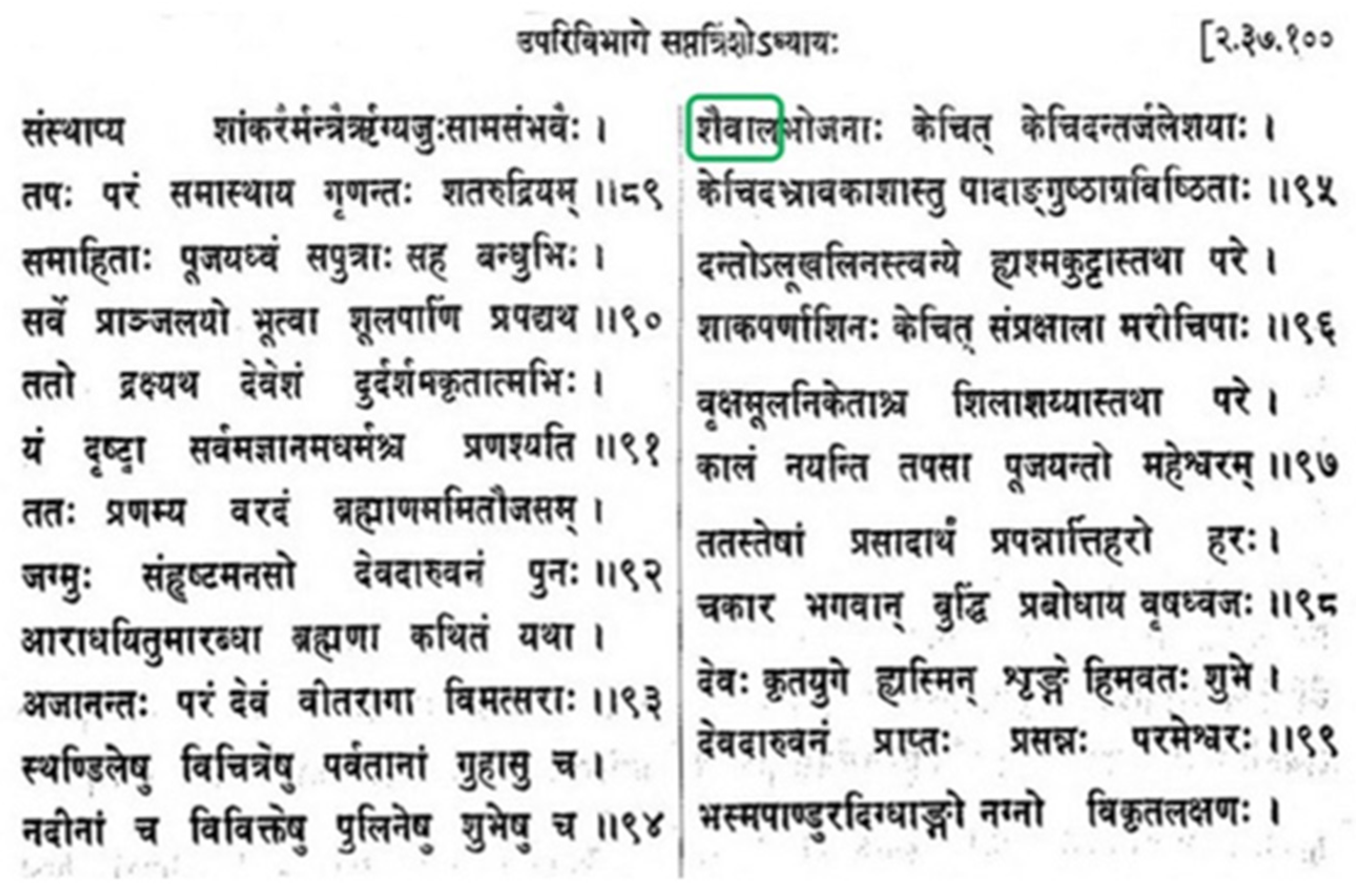

4.3. Duckweed in Medieval Hindu Literature

“They bowed to the beneficent Brahma, unlimited in his power, and returned to the Pine (Himalayan cedar) Forest, their hearts rejoicing. They began to worship just as Brahma had advised them. Still not knowing the highest god, but without desire and without jealousy, some worshiped him on multicolored ritual platforms, some in mountain caves, and some on empty, auspicious riverbanks. Some ate duck-weed for food, some lay in water, and some stood on the tips of their toes, abiding amid the clouds. Others ate unground grain, or ground it with a stone. Some ate vegetable leaves, and some purified themselves by subsisting on moonbeams (rays of light [14]). Some dwelled at the foot of trees, and others made their beds upon rocks. In these ways they passed their time performing austerities and worshiping Siva.”

4.4. Duckweed and Ritual Purification by Yemeni Muslims

… For their use and that of travelers, a large cemented cistern had been dug which received the rainwater, and in which they (the residents of the huts) not only drew their drink, but also bathed and performed their ritual purifications. … It is permitted, according to them (the residents of the huts), to wash and bathe in water which is not flowing and therefore does not renew itself, provided that it is abundant enough; while a Sunni after immersion in this way would consider himself impure, religiously speaking, as before. … the Yemenites claim, and perhaps believe, that the duckweed which covers the surface of stagnant waters, including their cisterns, is able to purify them (the waters), and they (the Yeminites) would not want to use standing water for purification where they would not see some (duckweed) floating. I must point out that this sect to which the inhabitants of Yemen belong is Zaydism. (translated by KSS).

5. Duckweed in Ancient Secular and Religious Poetry

5.1. Poetic Duckweed in Japanese Culture

5.2. Duckweed in Classical Chinese Poetry of the Ming Dynasty

“The east wind comes, and in a moment the end of spring is here;

Day after day, on the clear river, I sorrow for white duckweed.

Toward the north, the cloudy sky is lacking any road;

From the west, over heaven and earth, haze and dust are seen.

Having known high station and low, I see how they are related,

When things come up, in safely or peril, remember the men of old…”

“Reeds grow at the mouth of a wintry pond;

Daily mated to the floating duckweed.

Breeze and ripples rock their stems;

They eddy and drift like a traveler’s roaming.”

5.3. Duckweed in the Hebrew Scriptures, Book of Psalms

For the choir master; a Psalm, by David.

I fervently hoped for the Lord,

and He turned to me and heard my cry.

And He lifted me, from a turbulent watery dungeon,

from the mud of the yawvein.

And He set my feet upon a rock,

directing my steps…

For the conductor; upon shoshanim (a musical instrument), [a Psalm] of David.

Save me O God,

for the waters have reached my neck.

I have sunk,

in the depths of yawvein there is no foothold.

I have entered deep waters,

the current is sweeping me…

6. Local Names for Duckweed in Antiquity and in the Middle Ages

7. Discussion

A Case of Ethnobotanical Convergence?

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landolt, E. The Family of Lemnaceae—A Monographic Study; Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes der ETH, Stiftung Ruebel: Zurich, Switzerland, 1986; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bog, M.; Appenroth, K.J.; Sree, K.S. Duckweed (Lemnaceae): Its Molecular Taxonomy. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleiden, M.J. Prodromus Monographiae Lemnacearum oder Conspectus generum atque specierum. Linnaea 1839, 13, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, W.S. Nonphotosynthetic light requirement in Lemna minor and its partial satisfaction by kinetin. Science 1957, 126, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, K.; Appenroth, K.J.; Borisjuk, L.; Edelman, M.; Heinig, U.; Jansen, M.A.K.; Oyama, T.; Pasaribu, B.; Schubert, I.; Sorrels, S.; et al. Return of the Lemnaceae: Duckweed as a model plant system in the genomics and postgenomics era. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 3207–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvaček, Z. Limnobiophyllum krassilov—A fossil link between Araceae and Lemnaceae. Aquat. Bot. 1995, 50, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, J.; Gandolfo, M.A.; Cúneo, N.R.; Zamaloa, M.C. Fossil Araceae from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina, with implications on the origin of free-floating aquatic aroids. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2014, 211, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emson, D. Ecology and Palaeoecology of Diatom—Duckweed Relationships. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Geography University College London and Department of Botany Natural History Museum, University College London, London, UK, 2015. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1462713/1/Dave_Emson_PhD.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Petrova-Tacheva, V.; Alekova, S.; Ivanov, V. Lemna minor L. and folk medicine. Rheumatism 2019, 9, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Theophrastus. Enquiry into Plants, Books 1–5; Hort, A., Translator; Loeb Classical Library; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dioscorides. De Materia Medica—The Herbal by Dioscorides the Greek. A New Indexed Version in Modern English; Osbaldeston, T.A., Ed.; Osbaldeston, T.A., Translator; IBIDIS Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2000; Available online: http://www.cancerlynx.com/dioscorides.html (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- The Divine Farmer’s Materia Medica (Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing); Shou-Zhong, Y., Translator; Blue Poppy Press, Inc.: Boulder, CO, USA, 1998; Available online: https://archive.org/stream/ShenNongBenCaoLingTheDivineFarmersMateriaMedica/ShenNong%20Ben%20Cao%20ling%28The%20Divine%20Farmers%20Materia%20Medica%29_djvu.txt (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Bryant, D. The Great Recreation: Ho Ching-Ming (1483–1521) and His World; Brill. Leiden: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.S. The Kurma Purana; All-India Kashiraj Trust: Varanasi, India, 1972; p. 507. Available online: https://archive.org/details/kurmapuranaTRkashirajtrust1972/page/n559/mode/2up (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Theophrastus. De Historia Plantarum; Gaza, T., Translator; Apud Gulielmum Gazeium; Free eBook from the Internet Archive; Nicolaus Bacquenoius: Lyon, France, 1552; Available online: https://archive.org/details/mobot31753000811833 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Chisholm, H. (Ed.) Gaza, Theodorus. In Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1911; Volume 11, pp. 543–544. [Google Scholar]

- Herbermann, C. (Ed.) Theodore of Gaza. In Catholic Encyclopedia; Robert Appleton Company: New York, NY, USA, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Theophrastus. Gaza, Theodorus: De Historia Plantarum, in: Noscemus Wiki. 1913. Available online: http://wiki.uibk.ac.at/noscemus/De_historia_plantarum (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Papadopoulos, J.K. Greek protohistories. World Archaeol. 2018, 50, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theophrastus. Enquiry into plants, and minor works on odours and weather signs. Nature 1917, 99, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, J. A Review of Paul Millett’s, Theophrastus and His World; Proc. Camb. Philol Soc, (Suppl.) 2007, 33; Bryn Mawr Classical Review: Bryn Mawr, PA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2009/2009.10.55/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Raanan, M. Velo Beyeroka Shehalpnei Hamayim (Hebrew). Available online: https://daf-yomi.com/DYItemDetails.aspx?itemId=55044 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Wetland Management for Waterfowl Handbook. Common Moist-Soil Plants Identification Guide 70–127; Nelms, K.D., Ballinger, B., Boyles, A., Eds.; Natural Resources Conservation Service: Mississippi, USA, 2007. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_016986.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Bolles, D. A Translation of the Edited Text of Ritual of the Bacabs. 2003. Available online: http://davidsbooks.org/www/Bacabs.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- De Materia Medica: Libri Veiusdem de Venenis Libri Duo. Translated by Janus Antonius Saracenus. 1598. Available online: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb10994207?page=488 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Russell, M. Arthur and the Kings of Britain: The Historical Truth behind the Myths; Amberley Publishing: Stroud, UK, 2017; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein-Prasser, K.; Kanbay, F.; Koethe, R. Die Bewährte Heilkunde der Hildegard von Bingen (The Approved Physic of Hildegard of Bingen); FR text edition; Reader’s Digest: Hamburg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bingen, H. Ursachen und Behandlung der Krankheiten (Causa et Curae). (Reasons and Treatment of Diseases); Schulz, H., Translator; Verlag der Aeztlichen Rundschau Otto Gmelin: Muenchen, Germany, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bingen, H. Ursachen und Behandlung der Krankheiten (Causa et Curae). (Reasons and Treatment of Diseases); Schulz, H.; Karl, F., Translators; Haug Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzka, G.; Strehlow, W. Große Hildegard-Apotheke. (Great Hildegard Apothecary); Christiana-Verlag: Kisslegg-Immenried, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bingen, H. Heilwissen (Knowledge of Healing); Kaiser, P., Translator; FV Editions; Shambhala Pubs: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. El Mirador, the Lost City of the Maya. 2011. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/el-mirador-the-lost-city-of-the-maya-1741461/ (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Freidel, D.A.; Schele, L. Kingship in the late preclassic Maya lowlands: The instruments of power and places of ritual power. Am. Anthropol. 1988, 90, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doemel, K. Mayan Medicine: Rituals and Plant Use by Mayan Ah-Men. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin, La Crosse, WI, USA, 2013. Available online: https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/66629/Doemel_Thesis.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Knowlton, T.W. Flame, icons and healing: A colonial Maya ontology. Colon. Latin Am. Rev. 2018, 27, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.L. The Classic Maya Calendar and Day Numbering System. 1995. Available online: https://www.eecis.udel.edu/~mills/maya.html (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Ferrier, J.; Pesek, T.; Zinck, N.; Curtis, S.; Wanyerka, P.; Cal, V.; Balick, M.; Arnason, J.T. A classic Maya mystery of a medicinal plant and Maya hieroglyphs. Heritage 2020, 3, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily Prayer book, Ha-Sidur Ha-Shalem; Birnbaum, P., Ed.; Hebrew Publ. Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1949; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- The Complete Artscroll Siddur; Scherman, N., Ed.; Mesorah Publications, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1984; p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- Bodleian Library MS. Huntington 621. Rabbi Tanhum Hayerushalmi’s Murfshid Al-Kafi: Dictionary of Terms in Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah (in Judaeo-Arabic, Hebrew). Folio 100r. Available online: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/06abea16-07ae-4bd6-80cc-be7773bb33ae/surfaces/cefe511e-365f-41d7-ba2e-3535273a5946/ (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Kraemer, J.L. Maimonides: The Life and World of One of Civilization’s Greatest Minds; Doubleday Religion: Cordoba, Spain, 2010; p. 640. [Google Scholar]

- Medical Works of Maimonides (in Hebrew); Montner, S., Ed.; Mosad Harav Kook: Jerusalem, Israel, 1959; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R.H. The origin of Linga worship. In Religions of India in Practice; Lopez, D.S., Jr., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 637–648. [Google Scholar]

- Rocher, R. Alexander Hamilton (1762–1824). A Chapter in the Early History of Sanskrit Philology; American Oriental Society: New Haven, CO, USA, 1968; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Rocher, L. The Puranas. In A History of Indian Literature; Gonda, J., Ed.; Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1986; Volume II, p. Fasc. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, M.; Colt, M. Nutrient value of leaf vs. seed. Front. Chem. 2016, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appenroth, K.J.; Sree, K.S.; Böhm, V.; Hammann, S.; Vetter, W.; Leiterer, M.; Jahreis, G. Nutritional value of duckweeds (Lemnaceae) as human food. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appenroth, K.J.; Sree, K.S.; Bog, M.; Ecker, J.; Seeliger, C.; Böhm, V.; Lorkowski, S.; Sommer, K.; Vetter, W.; Tolzin-Banasch, K.; et al. Nutritional value of the duckweed species of the genus Wolffia (Lemnaceae) as human food. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sree, K.S.; Dahse, H.M.; Chandran, J.N.; Schneider, B.; Jahreis, G.; Appenroth, K.J. Duckweed for human nutrition: No cytotoxic and no anti-proliferative effects on human cell lines. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2019, 74, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mes, J.J.; Esser, D.; Somhorst, D.; Oosterink, E.; van der Haar, S.; Ummels, M.; Siebelink, E.; van der Meer, I.M. Daily intake of Lemna minor or spinach as vegetable does not show significant difference on health parameters and taste preference. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolt, E.; Kandeler, R. The Family of Lemnaceae—A Mono-Graphic Study; Veroeffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Instutes der ETH; Stiftung Ruebel: Zurich, Switzerland, 1987; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tawil, H.; Miodoenik, S.; Goloubinoff, P. Operation Esther: Opening the Door for the Last Jews of Yemen; Belkis Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Botta, P.E. Relations d’un Voyage Dans l’Yémen, Entrepris en 1837 Pour le Museum D’Histoire Naturelle de Paris; B. Duprat: Paris, France, 1841; p. 148. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k58013253/f21.item.texteImage.zoom (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Ozengin, N.; Elmaci, A. Performance of Duckweed (Lemna minor L.) on different types of wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Biol. 2007, 28, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, P.; Sree, K.S.; Appenroth, K.J. Duckweeds for water remediation and toxicity testing. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2016, 98, 1127–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovden, E. Rainwater Harvesting Cisterns and Local Water Management. Master’s Thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2006. Available online: https://bora.uib.no/bora-xmlui/bitstream/handle/1956/2001/Masteroppgave_Hovden.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- DeBusk, T.A.; Ryther, J.H.; Williams, L.D. Evapotranspiration of Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms and Lemna minor L. in central Florida: Relation to canopy structure and season. Aquat. Bot. 1983, 16, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirane, H. Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600, Abridged; Columbia University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y.-I. History and culture fostered by rice. Highlighting Jpn. 2020, 150, 6–7. Available online: https://www.gov-online.go.jp/pdf/hlj/20201101/06-07.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Li, H.; Liang, X.Q.; Lian, Y.F.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.X. Reduction of ammonia volatilization from urea by a floating duckweed in flooded rice fields. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2009, 73, 1890–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T. Background. Duckweed 2015 Kyoto. Available online: http://www.duckweed2015.cosmos.bot.kyoto-u.ac.jp/background.html (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Borisjuk, N.; Chu, P.; Gutierrez, R.; Zhang, H.; Acosta, K.; Friesen, N.; Sree, K.S.; Garcia, C.; Appenroth, K.J.; Lam, E. Assessment, validation and deployment strategy of a two barcode protocols for facile genotyping of duckweed species. Plant Biol. 2015, 17, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hucker, C.O. The Ming Dynasty, Its Origins and Evolving Institutions; E-book; University of Michigan Center for Chinese Studies: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, W. A History of China. 1950. (The Project Gutenberg EBook). Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/11367/pg11367.html (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Book of Psalms, Sefer Tehillim Daat Mikrah (in Hebrew); Israel’s Leading Publishers: Jerusalem, Israel, 1990; Volume 1.

- Tehilim, a New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources; Feuer, A.C., Translator; Mesorah Publ. Ltd.: Rahway, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Book of Psalms. Tehillim, with Commentary by Rabbi Saaadia Gaon (in Judaeo-Arabic, Translated into Hebrew by Y. Chacham. 1966). Available online: https://tablet.otzar.org/book/book.php?book=8066&pagenum=1 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Amar, Z. Plants of the Bible (in Hebrew); Rubin Maas Inc.: Jerusalem, Israel, 2009; p. 247. Available online: https://kotar.cet.ac.il/KotarApp/Viewer.aspx?nBookID=102357889#3.118.6.default (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Miller, N.A. Tribal Poetics in Early Arabic Culture: The Case of Ashʿār al-Hudhaliyyīn. Ph.D. Thesis, The Faculty of the Division of the Humanities, Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Chicago University Press, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkhoj Dictionary. Available online: https://dict.hinkhoj.com/shaivaal-meaning-in-english.words (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Salmoni, B.A.; Loidolt, B.; Wells, M. Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen. The Huthi Phenomenon. Appendix B. Zaydism: Overview and Comparison to Other Versions of Shi‘ism; RAND Corp., National Defence Research Institute: California, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, J.A.; Teixidor-Toneu, I. Defining ‘Ethnobotanical Convergence’. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 639–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredient | Term Used by Hildegard | Plant Species | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin Nomenclature | Plant Family | ||

| Feverfew | Mutterkraut | Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch.Bip. | Asteraceae |

| Sage | Salbei | Salvia officinalis L. | Lamiaceae |

| Zedoary | Zitwer | Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe | Zingiberaceae |

| Fennel | Fenchel | Foeniculm vulgare (L.) Mill. | Apiaceae |

| Duckweed | Wasserlinsen | Lemna minor L. | Lemnaceae |

| Erected cinquefoil | Tormentillwurzel | Potentilla erecta L. (Raeusch.) | Rosaceae |

| Charlock mustard | Senf | Sinapis arvensis L. | Brassicaceae |

| Burdock | Klette | Arctium lappa L. | Asteraceae |

| Ingredient (Quantity) | Term Used by Hildegard | Plant Species | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin Nomenclature | Plant Family | |||

| Component I: powder | ||||

| Ginger root powder (2.5 g) | Ingwerwurzel | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Zingiberaceae | Both powders were mixed |

| Cinnamon (10 g) | Zimtrindenpulver | Cinnamomum verum J.Presl | Lauraceae | |

| Component II: juice | ||||

| Sage juice from leaves (2 g) | Salbei | Salvia officinalis L. | Lamiaceae | All plants were homogenized, pressed out and filtered. |

| Fennel juice (3 g) | Fenchelkrautsaft | Foeniculum vulgare (L.) Mill: | Apiaceae | |

| Common tansy juice (2 g), without flowers, collected in spring | Rainfarnkrautsaft | Tanacetum vulgaris L. | Asteraceae | |

| Component III: Honey wine | ||||

| 90 g Honey boiled in 1 L wine | All three components were mixed | |||

| White pepper (1.2 g) | Weisser Pfeffer | Piper nigrum L. | Piperaceae | |

| Other components | ||||

| Duckweed (20 g) | Wasserlinsen | Lemna minor L. | Lemnaceae | These other components were added to the three component mixture, mixed and filtered |

| Erected cinquefoil (40 g) | Blutwurz | Potentilla erecta L. (Raeusch.) | Rosaceae | |

| Charlock mustard (40 g) | Ackersenf | Sinapis arvensis L. | Brassicaceae | |

| Cleavers (15 g) | Labkraut | Galium aparine L. or Galium verum L. | Rubiaceae | |

| This is for cooling a high fever and for cooling a pox b. |

| With the protecting shade of my foot, the protecting shade of my hand |

| I cooled the pox. |

| Five c are my red d hailstones e, my white hailstones, my black hailstones, my yellow hailstones. |

| With them I cooled the pox. |

| Thirteen c are the layers of my red d liturgical vestment f, my white liturgical vestment, |

| my black liturgical vestment, my yellow liturgical vestment. |

| I seized the strength g of the pox. |

| A black fan is my symbol when I seized the strength of the pox. |

| With me descends certainly my white h duckweed i. |

| I seized the strength of the pox. |

| With me descends my white h water lily. |

| Then it happens that I seized the strength of the pox. |

| Soon I will do good with the protecting shade of my foot, the protecting shade of my hand. |

| Amen. j |

| When Fun’ya no Yasuhide became the third-ranked official of Mikawa Province and invited me to come sightseeing in the provinces, this was my reply: a | |

| wabinureba mi o ukikusa no ne o taete c sasou mizu araba inamu to zo omou | Lonely and forlorn as a duckweed {uki b kusa}: should flowing waters d beckon I think I’d follow. |

| Culture | Period of History | Local Name | Literal Meaning | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Han Dynasty, c.200 CE | Shui Ping | water weed | [12] |

| Shui Hua | water flower | [12] | ||

| Ming Dynasty, c.1500 CE | Fu Ping | floating duckweed | [13] | |

| Christian | Hildegard von Bingen c.1150 CE | Lemna | Duckweed | [28] |

| Greek | Theophrastus c.330 BCE | Lemnaa | water plant | [10] |

| Hebrew | Book of Psalms c.1000 BCE | Yawvein | duckweed | [65,66] |

| Tachlavb | duckweed | [42,67] | ||

| Talmud (Mishna) c.200 CE | Yaroka | greenery on water | [38] | |

| Hindu | Kurma purana c.700 CE | Shaivaal | weed on water c | [69,70] |

| Japanese | Ono no Komachi c.850 CR | Ukikusa Ne-nashi-k(g)usa | floating weeds weeds without a root | [58] [58] |

| Maya | Ritual of the Bicabs c.250 CE | Ixim ha | maize-water plant | [35] |

| Roman | Dioscorides c.70 CE | Lens | lentil-shaped | [11] |

| Yemini | Zaydism c.1000 CE d | Simsime | Sesame-seed e |

| Divine Farmer’s Materia Medica [12] | Ritual of the Bacabs [24,34,35] |

|---|---|

| Later Han Dynasty, eastern China (c. 200 CE) | Maya Classical Period, the Americas (250–900 CE) |

| Lemnaceae: Lemna, Spirodela | Lemnaceae: L. minor, W. brasiliensis |

| “treats fulminant heat” | “cooling a high fever” |

| Daoist influence | shaman incantation |

| “precipitates water qi” | “seized the kinam (strength) of the pox” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Edelman, M.; Appenroth, K.-J.; Sree, K.S.; Oyama, T. Ethnobotanical History: Duckweeds in Different Civilizations. Plants 2022, 11, 2124. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11162124

Edelman M, Appenroth K-J, Sree KS, Oyama T. Ethnobotanical History: Duckweeds in Different Civilizations. Plants. 2022; 11(16):2124. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11162124

Chicago/Turabian StyleEdelman, Marvin, Klaus-Juergen Appenroth, K. Sowjanya Sree, and Tokitaka Oyama. 2022. "Ethnobotanical History: Duckweeds in Different Civilizations" Plants 11, no. 16: 2124. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11162124

APA StyleEdelman, M., Appenroth, K.-J., Sree, K. S., & Oyama, T. (2022). Ethnobotanical History: Duckweeds in Different Civilizations. Plants, 11(16), 2124. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11162124