Natural and Historical Heritage of the Lisbon Botanical Gardens: An Integrative Approach with Tree Collections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. History of the Botanical Gardens of Lisbon

2.1.1. Botanical Garden of Ajuda (JBA)

2.1.2. Lisbon Botanical Garden (JBL)

2.1.3. Tropical Botanical Garden (JBT)

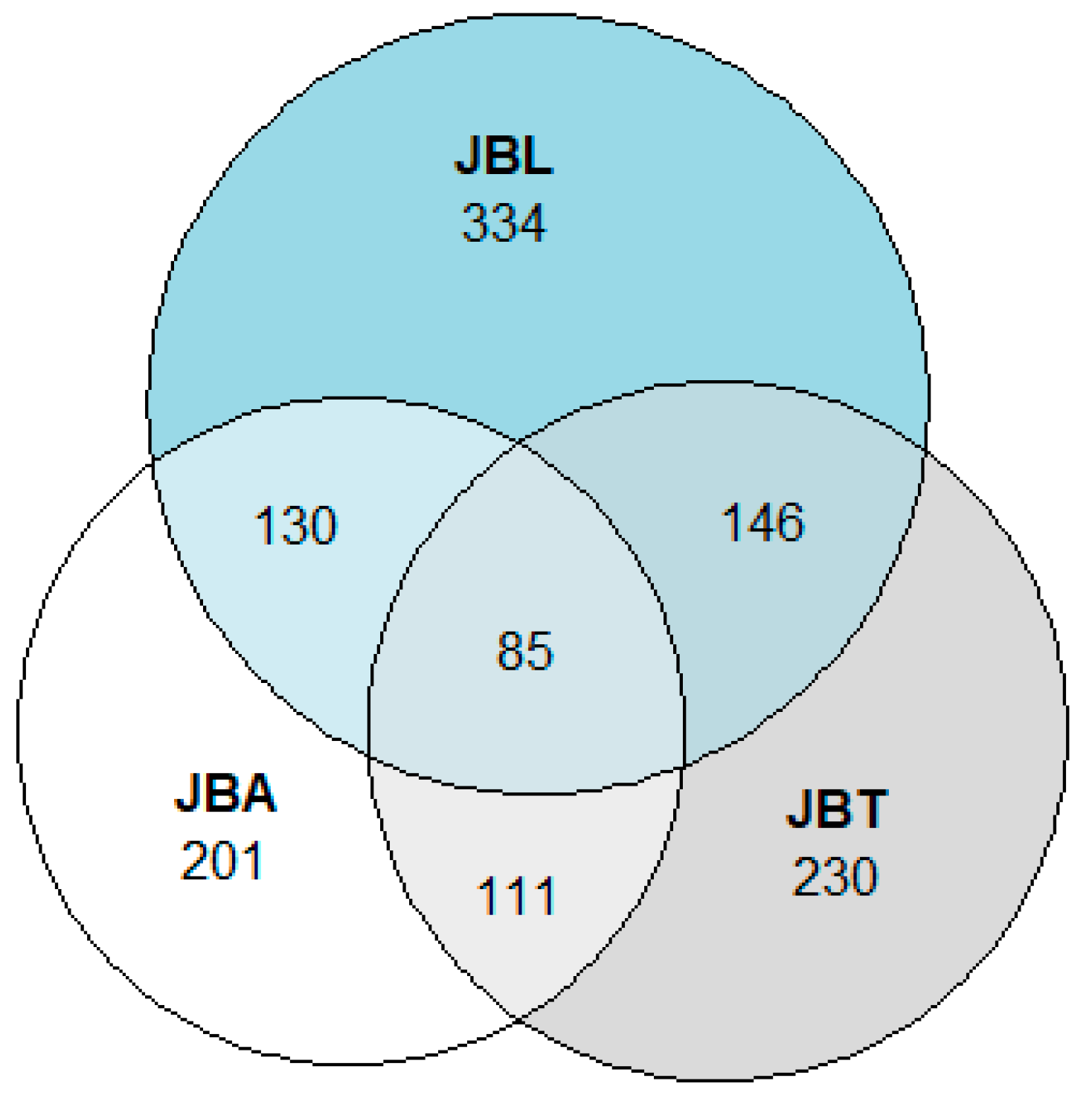

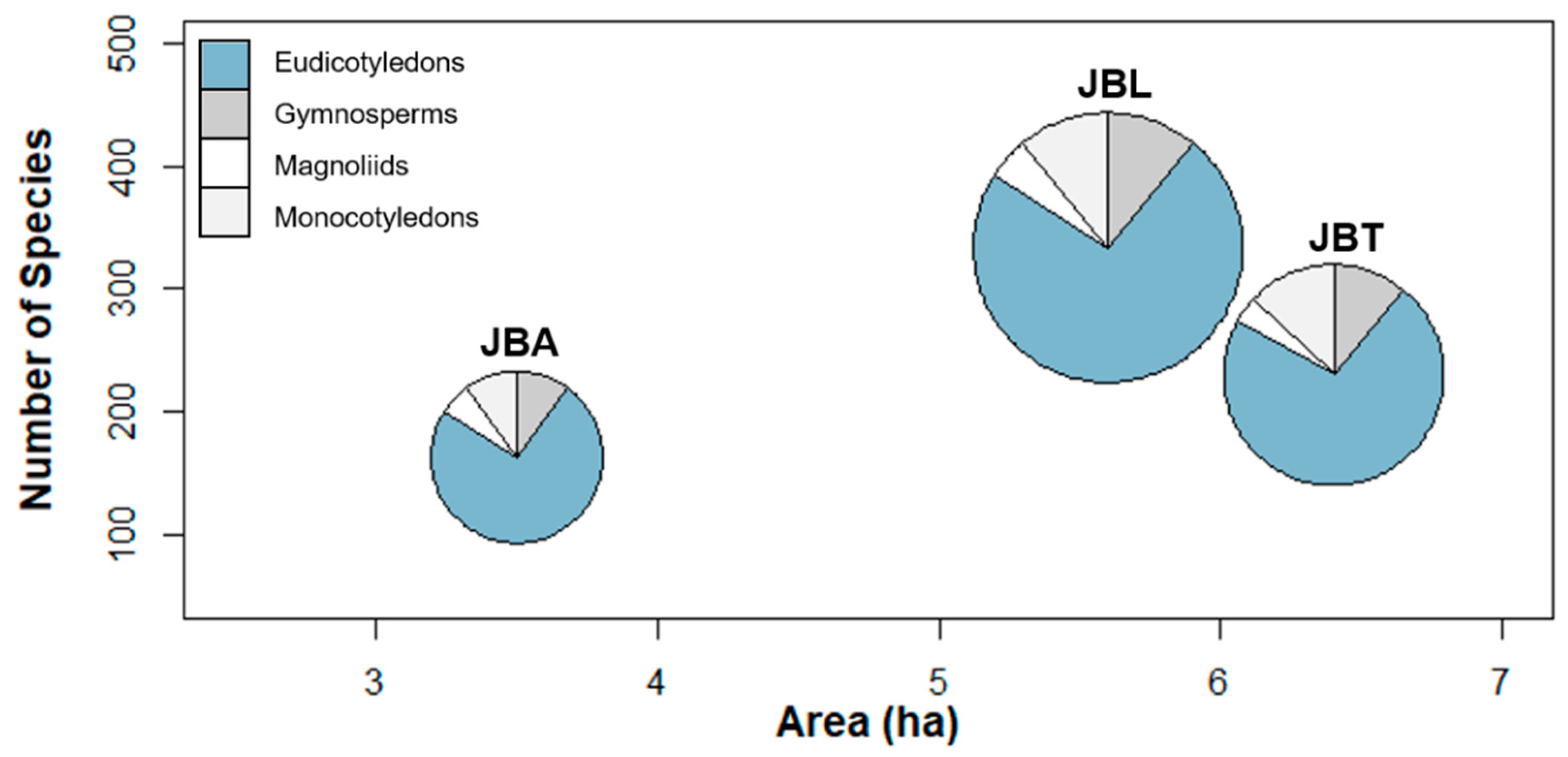

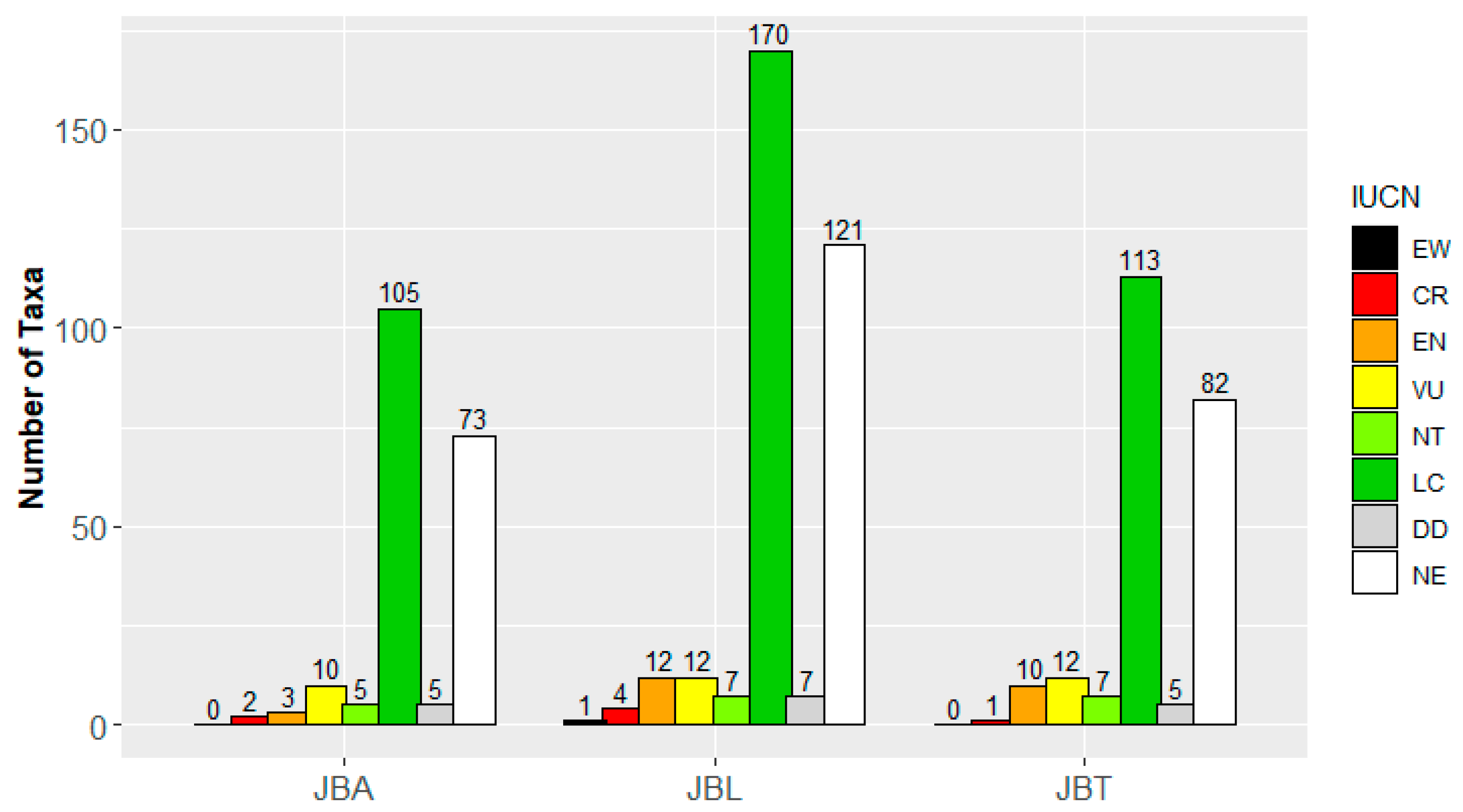

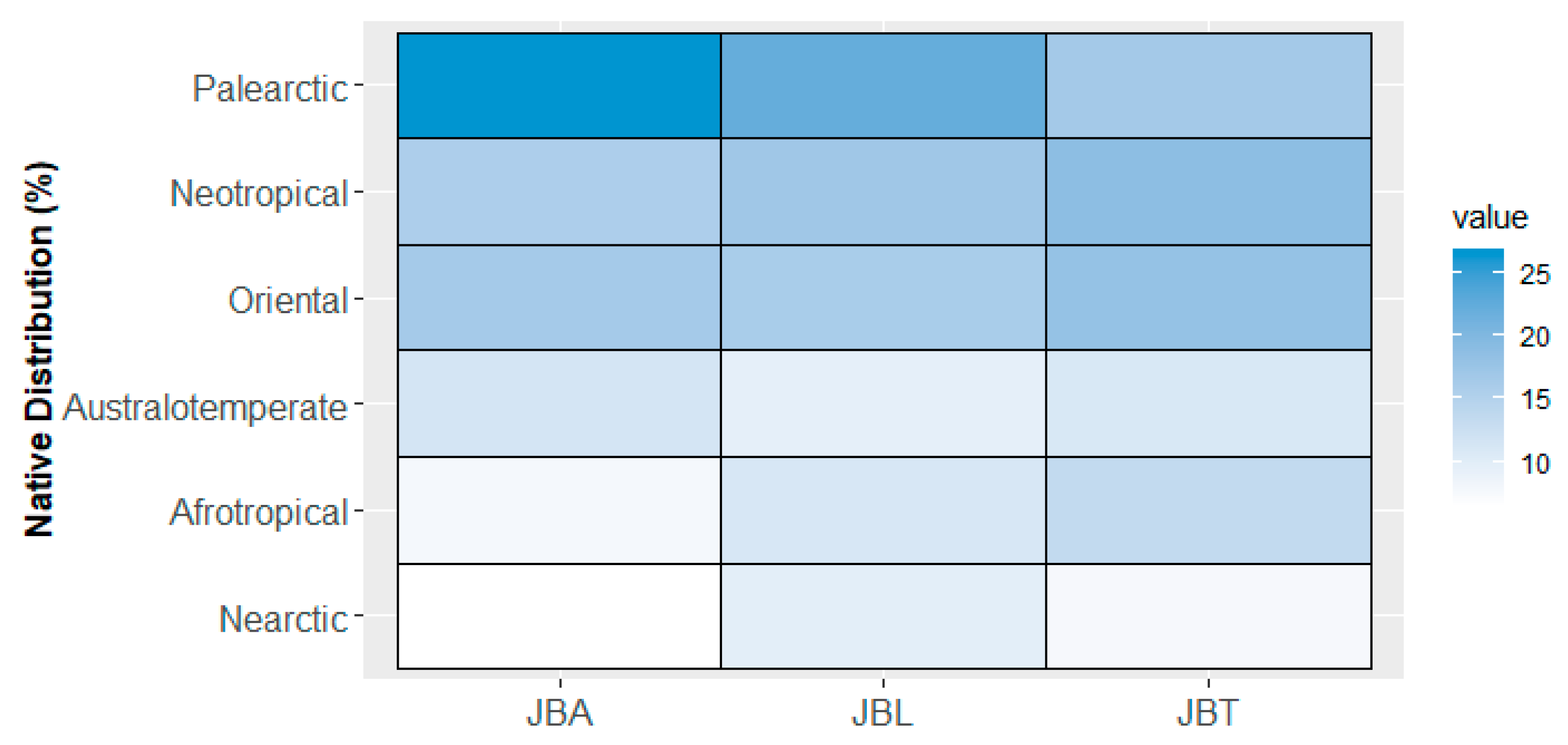

2.2. Tree Collections

2.2.1. Remarkable Species of JBA

2.2.2. Remarkable Species of JBL

2.2.3. Remarkable Species of JBT

3. Discussion

3.1. Natural and Historical Heritage of the Botanical Gardens of Lisbon

3.2. Outreach and Education Programs

3.3. Final Remarks

4. Materials and Methods

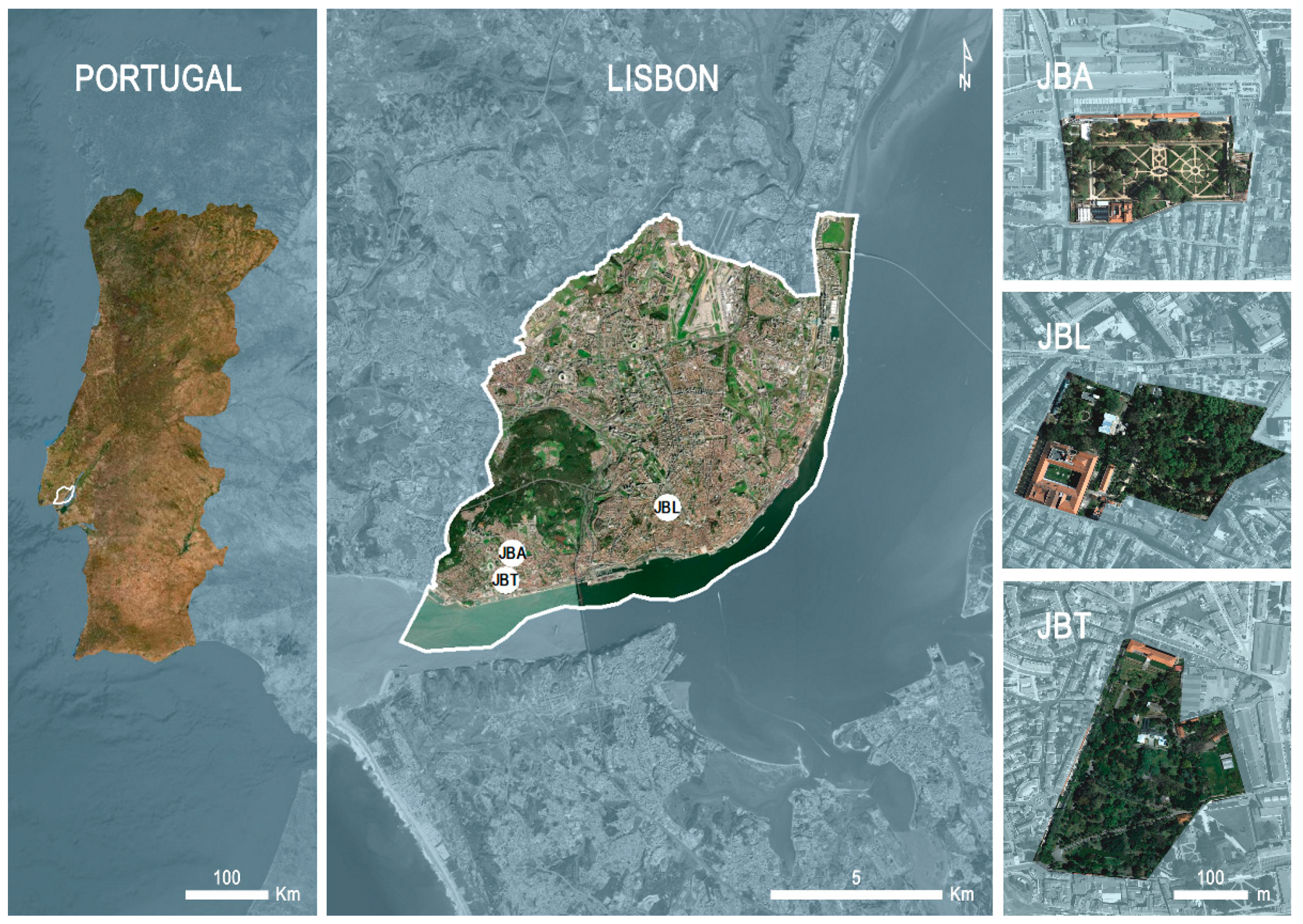

4.1. Studied Areas

4.1.1. Botanical Garden of Ajuda (JBA)

4.1.2. Lisbon Botanical Garden (JBL)

4.1.3. Tropical Botanical Garden (JBT)

4.2. Historical Data

4.3. Tree Layer Inventory

4.4. Database of the Tree Layers

4.5. Data Treatment

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brooks, T.M.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Fonseca, G.A.; Gerlach, J.; Hoffmann, M.; Lamoreux, J.F.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Pilgrim, J.D.; Rodrigues, A.S.L. Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science 2006, 313, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savard, J.P.L.; Clergeau, P.; Mennechez, G. Biodiversity concepts and urban ecosystems. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 48, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvey, A.A. Promoting and preserving biodiversity in the urban forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender, N.; Donnelly, G. Intersecting urban forestry and botanical gardens to address big challenges for healthier trees, people, and cities. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.D.; Parker, C.M.; Shackleton, C.M. The use and appreciation of botanical gardens as urban green spaces in South Africa. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, V.H. The future of plant conservation and the role of botanic gardens. Plant Divers. 2017, 39, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mounce, R.; Smith, P.; Brockington, S. Ex situ conservation of plant diversity in the world’s botanic gardens. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Sharrock, S. The contribution of botanic gardens to ex situ conservation through seed banking. Plant Divers. 2017, 39, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeli, T.; Dalrymple, S.; Godefroid, S.; Mondoni, A.; Müller, J.V.; Rossi, G.; Orsenigo, S. Ex situ collections and their potential for the restoration of extinct plants. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, M.; Shaw, K.; Beech, E.; Jones, M. Conserving the World’s Most Threatened Trees: A Global Survey of Ex Situ Collections; BCGI: Richmond, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-905164-61-5. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield, S.F. Botanic Gardens and the Conservation of Tree Species. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Version 2020-2. 2020. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Nath, C.D.; Aravajy, S.; Razasekaran, D.; Muthusankar, G. Heritage Conservation and Environmental Threats at the 192-Year-Old Botanical Garden in Pondicherry, India. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Cruz, C.S.; Alves, F.L.; Metelo, I.; Bogalho, V.; Pereira, H.M.; Luz Mathias, M.; Cardoso, M.C.; Almeida, J.; Sousa, M.; et al. Biodiversidade na Cidade de Lisboa: Uma Estratégia Para 2020; Câmara Municipal de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- BGCI. Global Tree Search Online Database; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: Richmond, UK, 2021; Available online: www.bgci.org/globaltree_search.php (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Caixinhas, M.L.; Liberato, M.C. African species in some green areas in Lisbon. An. Inst. Super. Agron. 2000, 48, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Martins-Loução, M.A.; Gaio-Oliveira, G. New Challenges to Promote Botany’s Practice Using Botanic Gardens: The Case Study of the Lisbon Botanic Garden. In Plant Biodiversity: Monotoring, Assessment and Conservation; Ansari, A.A., Gill, S.S., Abbas, Z.K., Naeem, M., Eds.; CABI Publishers: Wallingford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-78064-694-7. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, M.C.; Moura, I.; Pinheiro, M.; Nunes, M.C.; Palminha, A. Plantas do Jardim Botânico Tropical; Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Cavender, N.; Smith, P.; Marfleet, K. The Role of Botanic Gardens in Urban Greening and Conserving Urban Biodiversity; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: Richmond, UK, 2019; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier, I.; Pautasso, M. Species-richness of the living collections of the world’s botanical gardens—Patterns within continents. Kew Bull. 2010, 65, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, J.; Güsewell, S.; Kreft, H.; Kuzevanov, V.Y.; Lehvävirta, S.; Parmentier, I.; Pautasso, M. Species-richness patterns of the living collections of the world’s botanic gardens: A matter of socio-economics? Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandelli, D. Florae Lusitanicae et Brasiliensis Specimen; Academico-Regia: Coimbra, Portugal, 1788; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Felismino, D. Saberes, Natureza e Poder: Colecções Científicas da Antiga Casa Real Portuguesa; Museus da Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J. Ensino Agrícola-Colonial no Instituto Superior de Agronomia. O Jardim Colonial de Lisboa. Brotéria 1927, (special issue), 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liberato, M.; Afonso, M. Catálogo de Plantas do Jardim-Museu Agrícola Tropical; Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical e Fundação Berardo: Lisboa, Portugal, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, C.; Romeiras, M.M. Legacy of the scientific collections of the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, University of Lisbon: A critical review and outlook. Conserv. Património 2020, 33, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, D.L.; Hickey, L.J.; Wing, S.L. Ecological conservatism in the ‘living fossil’ Ginkgo. Paleobiology 2003, 29, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, I.; Marrero, Á.; Msanda, F.; Harrouni, C.; Gruenstaeudl, M.; Patiño, J.; Caujapé-Castells, J.; García-Verdugo, C. Iconic, threatened, but largely unknown: Biogeography of the Macaronesian dragon trees (Dracaena spp.) as inferred from plastid DNA markers. Taxon 2020, 69, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockey, R.A. Some comments on the origin and evolution of conifers. Can. J. Bot. 1981, 59, 1932–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Arens, N.C.; Li, C. Range change in Metasequoia: Relationship to palaeoclimate. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2007, 154, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. A Worldwide Survey of Cultivated Metasequoia glyptostroboides Hu & Cheng (Taxodiaceae: Cupressaceae) from 1947 to 2007. Bull. Peabody Mus. Nat. Hist. 2007, 48, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, J.E.M. Na linha dos descobrimentos dos séculos XV e XVI-Intercâmbio de plantas entre a África Ocidental e a América. Rev. de Ciências Agrárias 2019, 36, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azambuja, S.T. Real Quinta das Necessidades: Um Fio Condutor na Arte dos Jardins em Portugal. In Necessidades: Jardins e Cerca.; Castel-Branco, C., Ed.; Livros Horizonte/Jardim Botânico da Ajuda: Lisboa, Portugal, 2001; pp. 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bogoni, J.A.; Muniz-Tagliari, M.; Peroni, N.; Peres, C.A. Testing the Keystone Plant Resource Role of a Flagship Subtropical Tree Species (Araucaria angustifolia) in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.; Ladio, A.; Peroni, N. Landscapes with Araucaria in South America: Evidence for a Cultural Dimension. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, C.L.; Scarano, F.R.; Assad, E.D.; Joly, C.A.; Metzger, J.P.; Strassburg, B.B.N.; Tabarelli, M.; Fonseca, G.A.; Mittermeier, R.A. From Hotspot to Hopespot: An Opportunity for the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibrian, A.; Hird Meyer, A.; Oleas, N.; Ma, H.; Meerow, A.; Francisco-Ortega, J.; Griffith, M. What is the conservation value of a plant in a Botanic Garden? Using indicators to improve management of ex situ collections. Bot. Rev. 2013, 79, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Insect Killing Our Palm Trees. EU Efforts to Stop the Red Palm Weevil; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2011; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi, B.; Clematis, F.; Curir, P.; Monroy, F. Susceptibility and possible resistance mechanisms in the palm species Phoenix dactylifera, Chamaerops humilis and Washingtonia filifera against Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier, 1790) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2016, 106, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, L.; Lehvävirta, S. Botanic Gardens in the Age of Climate Change. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. The Challenge for Botanic Garden Science. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EGCA. European Green Capital Award (European Union). 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/winning-cities/2020-lisbon/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- UNDP. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). 2015. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Hotimah, O.; Wirutomo, P.; Alikodra, H. Conservation of World Heritage Botanical Garden in an Environmentally Friendly City. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.L.; Chambel, T.; Castro Rego, F.; Carvalho, P. Restoration and Recovery of the Garden at the end of the Twentieh Century. In Botanic Gardens of Ajuda; Castel-Branco, C., Ed.; Livros Horizonte e Associação dos Amigos do Jardim Botânico da Ajuda: Lisbon, Portugal, 1999; pp. 174–204. [Google Scholar]

- Qumsiyeh, M.; Handal, E.; Chang, J.; Abualia, K.; Najajrah, M.; Abusarhan, M. Role of Museums and Botanical Gardens in Ecosystem Services in Developing Countries: Case Study and Outlook. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 74, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, C. de Jardim Botânico da Ajuda. In Guia de Portugal Artístico: Jardins Parques e Tapadas; Ramalho, M.C., Ed.; Of. Gráficas da Casa Portuguesa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1935; Volume II, pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Palhinha, R.T. Jardim Botânico da Faculdade de Ciências. In Guia de Portugal Artístico: Jardins Parques e Tapadas; Ramalho, M.C., Ed.; Of. Gráficas da Casa Portuguesa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1935; Volume II, pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, C.N. Jardim Botânico da Faculdade de Ciências de Lisboa: Guia; Imprensa Portuguesa: Porto, Portugal, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Vandelli, D. Memória Sobre a Necessidade de Uma Viagem Filosófica Feita Pelo Reino e Depois Nos Seus Domínios; Memórias Económicas Inéditas, Academia das Ciências de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Brigola, J.C. Colecções, Gabinetes e Museus em Portugal No Século XVIII; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian/Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia: Lisboa, Portugal, 2003; p. 614. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara, P.P. Descripção Geral de Lisboa em 1839 ou Ensaio Histórico de Tudo Quanto Esta Capital Contém de Mais Notável, e Sua História Política e Literária Até o Tempo Presente; Tip. da Academia das Bellas Artes: Lisboa, Portugal, 1839. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, C.C. O Jardim Botânico Tropical-IICT e Seus Espaços Construídos: Uma Proposta de Reprogramação Funcional e Museológica Integrada; Dissertação para Obtenção do grau de Mestre em Museologia e Museografia; Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Belas Artes: Lisboa, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Castel-Branco, C. Botanic Gardens of Ajuda; Livros Horizonte e Associação dos Amigos do Jardim Botânico da Ajuda: Lisbon, Portugal, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Castel-Branco, C. Félix de Avelar Brotero; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, M.A. O Jardim Botânico da Ajuda [Botanic Garden of Ajuda]; Final Report of the Landscape Architecture Degree; Instituto Superior de Agronomia: Lisboa, Portugal, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Fragateiro, B. de O. Jardim Colonial (Belém). In Guia de Portugal Artístico: Jardins Parques e Tapadas; Ramalho, M.C., Ed.; Of. Gráficas da Casa Portuguesa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1935; Volume II, pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gardère, M.L.; Duarte, M.C.; Moraes, P.L.R.; Muller, S.; Romeiras, M.M. L’expédition scientifique de João da Silva Feijó aux îles du Cap Vert (1783–1796) et les tribulations de son herbier. Adansonia 2019, 41, 101–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morembert, T.M. Henri Navel (1878–1963); Mémoires de l’Académie Nationale de Metz: Metz, France, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, A.D. A Linguagem do Império nas Esculturas do Jardim Botânico Tropical em Lisboa. Rev. Bras. de História da Mídia 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Silva, I.C. Belém: Monografia Histórica; Junta de Freguesia de Santa Maria de Belém: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, L.H. Manual of Cultivated Plants; The MacMillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, L.H.; Bailey, E.Z. Hortus-Third. A Concise Dictionary of Plants Cultivated in the United States and Canada; The MacMillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J.; Knees, S.G.; Cubey, H.S.; Shaw, J.M.H. The European Garden Flora. Flowering Plants: A Manual for the Identification of Plants Cultivated in Europe, Both Out-of-Doors and under Glass; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eggli, U. Illustrated Handbook of Succulent Plants: Monocotyledons; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.A. Lycopodiaceae-Umbelliferae. Nova Flora de Portugal Continente e Açores 1971, 1, 647. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.A. Clethraceae-Compositae. Nova Flora de Portugal Continente e Açores 1984, 2, 659. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.A.; Afonso, M.L.R. Alismataceae-Iridaceae. Nova Flora de Portugal Continente e Açores 1994, 3, fasc. 1. 181. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.A.; Afonso, M.L.R. Gramineae. Nova Flora de Portugal Continente e Açores 1998, 3, fasc. 3. 286. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.A.; Afonso, M.L.R. Juncaceae-Orchidaceae. Nova Flora de Portugal Continente e Açores 2003, 3, fasc. 2. 187. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, A.; Griffiths, M.; Levy, M. The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening; The Macmillan Press Limited: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, S.M.; Cullen, J. The European Garden Flora: A Manual for the Identification of Plants Cultivated in Europe, Both Out-of-Doors and under Glass; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. 2020. Available online: http://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- WFO. World Flora Online. 2021. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Morrone, J.J. Biogeographical Regions under Track and Cladistic Scrutiny. J. Biogeogr. 2002, 29, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF. Global Biodiversity Information Facility. 2020. Available online: https://www.gbif.org (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, Use R! 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24275-0. [Google Scholar]

| Family/Taxa | JBA | JBL | JBT | Habit | IUCN a | Native Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacardiaceae | ||||||

| Harpephyllum caffrum Bernh. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Pistacia lentiscus L. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Pistacia vera L. | X | Tree | NT | Palearctic | ||

| Pleiogynium timoriense (A.DC.) Leenh. | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate—Oriental | ||

| Schinus latifolia (Gillies ex Lindl.) Engl. | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Schinus molle L. | X | Tree | NE | Andean—Neotropical | ||

| Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical |

| Spondias mombin L. | X | Tree | LC | Andean—Neotropical | ||

| Annonaceae | ||||||

| Annona cherimola Mill. | X | X | Tree | LC | Andean | |

| Apiaceae | ||||||

| Heteromorpha arborescens var. abyssinica (Hochst. ex A. Rich.) H. Wolff | X | Tree | NE | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Apocynaceae | ||||||

| Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth. and Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Acokanthera oppositifolia (Lam.) Codd. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Carissa bispinosa (L.) Desf. ex Brenan | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Carissa macrocarpa (Eckl.) A.DC. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | |

| Cascabela thevetia (L.) Lippold | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Nearctic—Neotropical |

| Nerium oleander L. | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical—Oriental—Palearctic |

| Plumeria alba L. | X | X | Shrub | NE | Neotropical | |

| Aquifoliaceae | ||||||

| Ilex aquifolium L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Ilex perado Aiton subsp. azorica Tutin | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic | ||

| Araliaceae | ||||||

| Oreopanax nymphaeifolius (Hibberd) Decne. and Planch. ex G.Nicholson | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical | |

| Plerandra elegantissima (H.J.Veitch ex Mast.) Lowry, G.M.Plunkett and Frodin | X | X | Tree | EN | Neoguinean | |

| Pseudopanax lessonii (DC.) K.Koch | X | Tree | NE | Neozelandic | ||

| Schefflera actinophylla (Endl.) Harms | X | Tree | LC | Australotropical—Oriental | ||

| Schefflera venulosa (Wight and Arn.) Harms | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Tetrapanax papyrifer (Hook.) K.Koch | X | Shrub | LC | Oriental | ||

| Araucariaceae | ||||||

| Agathis robusta (C.Moore ex F.Muell.) F.M.Bailey | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate—Neoguinean |

| Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze | X | Tree | CR | Neotropical | ||

| Araucaria bidwillii Hook. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate |

| Araucaria columnaris (G.Forst.) Hook. | X | X | Tree | LC | Neoguinean | |

| Araucaria cunninghamii Mudie | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate—Neoguinean |

| Araucaria heterophylla (Salisb.) Franco | X | X | X | Tree | VU | Neozelandic |

| Arecaceae | ||||||

| Archontophoenix cunninghamiana (H.Wendl.) H.Wendl. and Drude | X | Rosette tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Arenga pinnata (Wurmb) Merr. | X | Rosette tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Bismarckia nobilis Hildebrandt and H.Wendl. | X | Rosette tree | LC | Afrotropical | ||

| Brahea armata S.Watson | X | X | Rosette tree | LC | Neotropical | |

| Brahea edulis H.Wendl. ex S.Watson | X | X | Rosette tree | EN | Neotropical | |

| Butia capitata (Mart.) Becc. | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Neotropical | |

| Butia eriospatha (Mart. ex Drude) Becc. | X | Rosette tree | VU | Neotropical | ||

| Chamaedorea pochutlensis Liebm. | X | Rosette tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Chamaedorea tepejilote Liebm. | X | Rosette tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Chamaerops humilis L. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Howea forsteriana (F.Muell.) Becc. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | VU | Australotemperate |

| Livistona australis (R.Br.) Mart. | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Australotemperate | |

| Livistona chinensis (Jacq.) R.Br. ex Mart. | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Phoenix canariensis H.Wildpret | X | X | X | Rosette tree | LC | Afrotropical |

| Phoenix dactylifera L. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Afrotropical—Palearctic |

| Phoenix loureiroi Kunth | X | X | Rosette tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Phoenix reclinata Jacq. | X | X | Rosette tree | LC | Afrotropical | |

| Phoenix rupicola T.Anderson | X | Rosette tree | NT | Oriental | ||

| Rhapis excelsa (Thunb.) Henry | X | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Oriental |

| Rhopalostylis baueri (Hook.f.) H.Wendl. and Drude | X | Rosette tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Rhopalostylis sapida (Sol. ex G.Forst.) H.Wendl. and Drude | X | Rosette tree | NE | Neozelandic | ||

| Sabal bermudana L.H. Bailey | X | X | Rosette tree | EN | Neotropical | |

| Sabal minor (Jacq.) Pers. | X | X | Rosette tree | LC | Nearctic—Neotropical | |

| Sabal palmetto (Walter) Lodd. ex Schult and Schult.f. | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Nearctic—Neotropical | |

| Serenoa repens (W.Bartram) Small | X | Rosette tree | NE | Nearctic | ||

| Syagrus romanzoffiana (Cham.) Glassman | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Neotropical | |

| Trachycarpus fortunei (Hook.) H.Wendl. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Oriental |

| Trachycarpus martianus (Wall. ex Mart.) H.Wendl. | X | Rosette tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Trithrinax brasiliensis Mart. | X | Rosette tree | DD | Neotropical | ||

| Washingtonia filifera (Rafarin) H.Wendl. ex de Bary | X | X | X | Rosette tree | NT | Nearctic—Neotropical |

| Washingtonia robusta H.Wendl. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Neotropical |

| Asparagaceae | ||||||

| Beaucarnea recurvata (K.Koch and Fintelm.) Lem. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | CR | Neotropical |

| Beaucarnea stricta (K.Koch and Fintelm.) Lem. | X | Rosette tree | VU | Neotropical | ||

| Cordyline australis (G.Forst.) Endl. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Neozelandic |

| Cordyline indivisa (G. Forst.) Endl. | X | Rosette tree | LC | Neozelandic | ||

| Dasylirion wheeleri S.Watson ex Rothr. | X | Rosette tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Dracaena draco (L.) L. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | VU | Afrotropical |

| Nolina parviflora (Kunth) Hemsl. | X | Rosette tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Yucca aloifolia L. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Nearctic—Neotropical |

| Yucca carnerosana (Trel.) McKelvey | X | Rosette tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Yucca gigantea Lem. | X | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Neotropical |

| Yucca gloriosa L. | X | X | Rosette tree | LC | Nearctic | |

| Yucca treculeana Carrière | X | Rosette tree | NE | Nearctic—Neotropical | ||

| Asphodelaceae | ||||||

| Aloidendron barberae (Dyer) Klopper and Gideon F.Sm. | X | X | Rosette tree | NE | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | |

| Asteraceae | ||||||

| Montanoa bipinnatifida (Kunth) K.Koch | X | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical |

| Podachaenium eminens (Lag.) Sch.Bip. ex Sch.Bip. | X | Shrub | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Berberidaceae | ||||||

| Berberis bealei Fortune | X | X | Shrub | NE | Oriental | |

| Berberis japonica (Thunb.) Spreng. | X | Shrub | NE | Palearctic | ||

| Betulaceae | ||||||

| Alnus cordata (Loisel.) Duby | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Betula pubescens Ehrh. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Corylus avellana L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Ostrya carpinifolia Scop. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Bignoniaceae | ||||||

| Catalpa bignonioides Walter | X | X | X | Tree | DD | Nearctic |

| Jacaranda mimosifolia D.Don | X | X | X | Tree | VU | Neotropical |

| Markhamia lutea (Benth.) K. Schum. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical | ||

| Radermachera sinica (Hance) Hemsl. | X | Tree | LC | Oriental—Palearctic | ||

| Spathodea campanulata P.Beauv. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical | ||

| Boraginaceae | ||||||

| Ehretia acuminata R.Br. | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate—Oriental—Neoguinean | ||

| Ehretia anacua (Terán and Berland.) I.M.Johnst. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Cactaceae | ||||||

| Cereus hildmannianus K.Schum. | X | Stem-succulent shrub | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Cereus hildmannianus subsp. uruguayanus (F.Ritter ex R.Kiesling) N.P.Taylor | X | X | Stem-succulent shrub | NE | Neotropical | |

| Opuntia leucotricha DC. | X | X | Stem-succulent shrub | LC | Neotropical | |

| Opuntia monacantha Haw. | X | Stem-succulent shrub | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Rhodocactus grandifolius (Haw.) F.M.Knuth | X | Stem-succulent shrub | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Calycanthaceae | ||||||

| Chimonanthus praecox (L.) Link | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Cannabaceae | ||||||

| Celtis australis L. subsp. australis | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Celtis caucasica Willd. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Celtis occidentalis L. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Celtis reticulata Torr. | X | Tree | NE | Nearctic | ||

| Celtis sinensis Pers. | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Casuarinaceae | ||||||

| Casuarina cunninghamiana Miq. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate—Australotropical |

| Elaeodendron papillosum Hochst. | X | Tree | NE | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Euonymus europaeus L. | X | X | Shrub | NE | Palearctic | |

| Euonymus japonicus Thunb. | X | X | Shrub | VU | Palearctic | |

| Maurocenia frangula Mill | X | Tree | NE | Afrotemperate | ||

| Cercidiphyllaceae | ||||||

| Cercidiphyllum magnificum (Nakai) Nakai | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic | ||

| Combretaceae | ||||||

| Terminalia australis Cambess. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Cornaceae | ||||||

| Cornus capitata Wall. | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Cornus walteri Wangerin | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Corynocarpaceae | ||||||

| Corynocarpus laevigatus J.R.Forst. and G.Forst. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Neozelandic |

| Cupressaceae | ||||||

| Chamaecyparis lawsoniana (A.Murray bis) Parl. | X | X | X | Tree | NT | Nearctic |

| Cupressus sempervirens L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Hesperocyparis glabra (Sudw.) Bartel | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Hesperocyparis lusitanica (Mill.) Bartel | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical |

| Hesperocyparis macnabiana (A.Murray bis) Bartel | X | Tree | VU | Nearctic | ||

| Hesperocyparis macrocarpa (Hartw.) Bartel | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic |

| Juniperus cedrus Webb and Berthel. | X | Tree | EN | Afrotropical | ||

| Juniperus chinensis L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental—Palearctic | |

| Juniperus phoenicea L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Juniperus sabina L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Juniperus virginiana L. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Metasequoia glyptostroboides Hu and W.C.Cheng | X | Tree | EN | Oriental | ||

| Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco | X | X | X | Tree | NT | Palearctic |

| Sequoia sempervirens (D.Don) Endl. | X | X | Tree | EN | Nearctic | |

| Taxodium distichum (L.) Rich. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Taxodium distichum var. mexicanum (Carrière) Gordon and Glend. | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Thuja occidentalis L. | X | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Nearctic |

| Thuja plicata Donn ex D.Don | X | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | |

| Curtisiaceae | ||||||

| Curtisia dentata (Burm.f.) C.A.Sm | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Didiereaceae | ||||||

| Portulacaria afra Jacq. | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate |

| Ebenaceae | ||||||

| Diospyros kaki L.f. | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental—Palearctic | |

| Diospyros lotus L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Diospyros virginiana L. | X | Tree | NE | Nearctic | ||

| Elaeagnaceae | ||||||

| Elaeagnus angustifolia L. | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Elaeagnus pungens Thunb. | X | Shrub | LC | Oriental | ||

| Ericaceae | ||||||

| Arbutus unedo L. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Eucommiaceae | ||||||

| Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. | X | Tree | VU | Oriental | ||

| Euphorbiaceae | ||||||

| Alchornea cordifolia (Schumach. and Thonn.) Müll.Arg. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Afrotropical | ||

| Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd. | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Baloghia inophylla (G.Forst.) P.S.Green | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Euphorbia ingens E.Mey. ex Boiss. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical | |

| Euphorbia pulcherrima Willd. ex Klotzsch. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Neotropical | |

| Euphorbia tirucalli L. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate—Oriental | |

| Euphorbia triangularis Desf. ex A. Berger | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | |

| Mallotus japonicus (L.f.) Müll.Arg. | X | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic | |

| Ricinus communis L. | X | X | Shrub | NE | Afrotropical | |

| Fabaceae | ||||||

| Albizia julibrissin Durazz. | X | Tree | NE | Oriental—Palearctic | ||

| Bauhinia acuminata L. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Australotropical—Oriental | |

| Bauhinia forficata Link | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Neotropical | |

| Bauhinia purpurea L. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Bauhinia variegata L. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Calliandra tweediei Benth. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Castanospermum australe A.Cunn. ex Mudie | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Ceratonia siliqua L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Cercis siliquastrum L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Dermatophyllum secundiflorum (Ortega) Gandhi and Reveal | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Erythrina americana Mill. | X | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | |

| Erythrina caffra Thunb. | X | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | |

| Erythrina crista-galli L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | |

| Erythrina lysistemon Hutch. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Erythrina speciosa Andrews | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Gleditsia triacanthos L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic |

| Inga edulis Mart. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical—Andean | ||

| Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit | X | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | |

| Libidibia paraguariensis (D.Parodi) G.P.Lewis | X | Tree | VU | Neotropical | ||

| Mimosa aculeaticarpa Ortega | X | Shrub | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Parkinsonia aculeata L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Andean—Nearctic—Neotropical | |

| Peltophorum dubium (Spreng.) Taub. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Prosopis chilensis (Molina) Stuntz | X | Tree | LC | Andean—Neotropical | ||

| Prosopis glandulosa Torr. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic—Neotropical | ||

| Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC. | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Prosopis laevigata (Humb. and Bonpl. ex Willd.) M.C.Johnst. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Robinia neomexicana A.Gray var. neomexicana | X | Tree | NE | Nearctic—Neotropical | ||

| Robinia pseudoacacia L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic |

| Schotia afra (L.) Thunb. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Schotia brachypetala Sond. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Schotia latifolia Jacq. | X | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | |

| Senna didymobotrya (Fresen.) H.S. Irwin and Barneby | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Afrotropical | |

| Sophora davidi (Franch.) Skeels | X | Shrub | NE | Oriental | ||

| Sophora microphylla Aiton | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neozelandic | ||

| Styphnolobium japonicum (L.) Schott | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental |

| Tara spinosa (Molina) Britton and Rose | X | X | Tree | NE | Andean—Neotropical | |

| Tipuana tipu (Benth.) Kuntze | X | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | |

| Vachellia farnesiana (L.) Wight and Arn. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Vachellia karroo (Hayne) Banfi and Galasso | X | X | Tree | NE | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | |

| Fagaceae | ||||||

| Fagus sylvatica L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Quercus alnifolia Poech | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Quercus coccifera L. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic | |

| Quercus faginea Lam. subsp. broteroi (Cout.) A.Camus | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic | ||

| Quercus faginea Lam. subsp. faginea | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Quercus ilex L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Quercus libani G.Olivier | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Quercus rotundifolia Lam. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Quercus suber L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Ginkoaceae | ||||||

| Ginkgo biloba L. | X | X | X | Tree | EN | Oriental |

| Hamamelidaceae | ||||||

| Parrotia persica C.A.Mey. | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic | ||

| Hydrophyllaceae | ||||||

| Wigandia urens (Ruiz and Pav.) Kunth | X | Shrub | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Juglandaceae | ||||||

| Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) K.Koch | X | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | |

| Juglans nigra L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | |

| Juglans regia L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Pterocarya fraxinifolia (Poir.) Spach | X | Tree | VU | Palearctic | ||

| Lamiaceae | ||||||

| Vitex agnus-castus L. | X | X | X | Tree | DD | Palearctic |

| Lauraceae | ||||||

| Cinnamomum burmanni (Nees and T.Nees) Blume | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J.Presl | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic |

| Cinnamomum tamala (Buch.-Ham.) T.Nees and Eberm. | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Cinnamomum verum J.Presl | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Laurus azorica (Seub.) Franco | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Laurus nobilis L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Ocotea foetens (Aiton) Baill. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical |

| Persea americana Mill. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical |

| Persea barbujana (Cav.) Mabb. and Nieto Fel. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical |

| Persea indica (L.) Spreng. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical |

| Lythraceae | ||||||

| Lagerstroemia indica L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental |

| Punica granatum L. | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic |

| Magnoliaceae | ||||||

| Liriodendron tulipifera L. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Magnolia champaca (L.) Baill. ex Pierre | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Magnolia compressa Maxim. | X | Tree | DD | Oriental | ||

| Magnolia grandiflora L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | |

| Magnolia tripetala (L.) L. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Magnolia× soulangeana Soul.-Bod. | X | Tree | NE | Hybrid | ||

| Malvaceae | ||||||

| Brachychiton acerifolius (A.Cunn. ex G.Don) F.Muell. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate |

| Brachychiton bidwillii Hook. | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Brachychiton discolor F. Muell. | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | |

| Brachychiton populneus (Schott and Endl.) R.Br. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate |

| Brachychiton rupestris (T.Mitch. ex Lindl.) K.Schum. | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Ceiba crispiflora (Kunth) Ravenna | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Ceiba insignis (Kunth) P.E.Gibbs and Semir | X | X | Tree | NE | Andean | |

| Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertn. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Ceiba speciosa (A.St.-Hil., A.Juss. and Cambess.) Ravenna | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical |

| Dombeya burgessiae Gerrard ex Harv. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical | |

| Dombeya rotundifolia (Hochst.) Planch. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Dombeya tiliacea (Endl.) Planch. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Dombeya × cayeuxii André | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Hybrid |

| Firmiana simplex (L.) W.Wight | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Grewia occidentalis L. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Hibiscus mutabilis L. | X | X | X | Shrub | NE | Oriental |

| Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. | X | X | X | Shrub | NE | Oriental |

| Hibiscus syriacus L. | X | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Oriental |

| Lagunaria patersonia (Andrews) G.Don | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | |

| Malvaviscus arboreus Dill. ex Cav. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Neotropical | |

| Pachira aquatica Aubl. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Phymosia umbellata (Cav.) Kearney | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Neotropical | |

| Tilia × moltkei Späth ex C.K.Schneid. | X | Tree | NE | Hybrid | ||

| Tilia dasystyla Steven | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Tilia platyphyllos Scop. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Tilia tomentosa Moench | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Meliaceae | ||||||

| Cedrela odorata L. | X | X | Tree | VU | Neotropical | |

| Melia azedarach L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate—Australotropical—Neioguinean—Oriental |

| Trichilia emetica Vahl | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical | ||

| Trichilia havanensis Jacq. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Menispermaceae | ||||||

| Cocculus laurifolius DC. | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Monimaceae | ||||||

| Peumus boldus Molina | X | Tree | LC | Andean | ||

| Moraceae | ||||||

| Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L’Hér. ex Vent. | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental—Palearctic | |

| Ficus altissima Blume | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Ficus aurea Nutt. | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Ficus benjamina L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate—Oriental |

| Ficus carica L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Ficus coronata Spin | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Ficus elastica Roxb. ex Hornem. | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Ficus eximia Schott | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Ficus habrophylla G.Benn. ex Seem. | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Ficus luschnathiana (Miq.) Miq. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Ficus lyrata Warb. | X | Tree | NE | Afrotropical | ||

| Ficus macrophylla Desf. ex Pers. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate |

| Ficus microcarpa L.f. | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate—Neoguinean—Oriental | |

| Ficus religiosa L. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental |

| Ficus rubiginosa Desf. ex Vent. | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Ficus rumphii Blume | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Ficus superba (Miq.) Miq. | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Ficus sur Forssk. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical | ||

| Ficus sycomorus L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical | |

| Ficus virens Aiton | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate—Australotropical—Oriental | ||

| Maclura pomifera (Raf.) C.K.Schneid. | X | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | |

| Morus alba L. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental |

| Morus nigra L. | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic | ||

| Myricaceae | ||||||

| Myrica faya Dryand. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Myrtaceae | ||||||

| Agonis flexuosa (Willd.) Sweet | X | Tree | NE | Australotropical | ||

| Corymbia maculata (Hook.) K.D.Hill and L.A.S.Johnson | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | X | X | X | Tree | NT | Australotropical—Australotemperate |

| Eucalyptus cladocalyx F.Muell. | X | Tree | VU | Australotemperate | ||

| Eucalyptus cornuta Labill. | X | Tree | NT | Australotemperate | ||

| Eucalyptus diversicolor F.Muell. | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate | ||

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate | ||

| Eucalyptus gomphocephala A.Cunn ex DC. | X | X | Tree | VU | Australotemperate | |

| Eucalyptus ovata Labill. | X | Tree | VU | Australotemperate | ||

| Eucalyptus robusta Sm. | X | Tree | NT | Australotemperate | ||

| Eucalyptus tereticornis Sm. | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate | |

| Eucalyptus × kirtoniana F.Muell. | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Eugenia involucrata DC. | X | Shrub | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Eugenia myrcianthes Nied. | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Eugenia uniflora L. | X | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | |

| Feijoa sellowiana (O.Berg) O.Berg | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Neotropical | |

| Leptospermum laevigatum (Gaertn.) F.Muell. | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Lophostemon confertus (R.Br.) Peter G.Wilson and J.T. Waterh. | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | |

| Melaleuca armillaris (Sol. ex Gaertn.) Sm. | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | |

| Melaleuca citrina (Curtis) Dum.Cours. | X | Shrub | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Melaleuca lanceolata Otto | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate | ||

| Melaleuca leucadendra (L.) L. | X | Tree | NE | Australotropical—Neoguinean | ||

| Melaleuca linearis Schrad. and J.C.Wendl. var. linearis | X | X | Shrub | NE | Australotemperate | |

| Melaleuca preissiana Schauer | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate | ||

| Melaleuca rugulosa (Link) Craven | X | Shrub | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Melaleuca styphelioides Sm. | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Melaleuca viminalis (Sol. ex Gaertn.) Byrnes | X | Shrub | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Melaleuca virens Craven | X | Shrub | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Metrosideros excelsa Sol. ex Gaertn. | X | X | Tree | NE | Neozelandic | |

| Myrtus communis L. | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical—Palearctic |

| Psidium cattleyanum Sabine | X | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical |

| Psidium guajava L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Andean—Neotropical | |

| Psidium guineense Sw. | X | Tree | LC | Andean—Neotropical | ||

| Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels | X | Tree | LC | Oriental—Australotropical | ||

| Syzygium jambos (L.) Alston | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Syzygium paniculatum Gaertn. | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | |

| Ochnaceae | ||||||

| Ochna serrulata (Hochst.) Walp. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | |

| Oleaceae | ||||||

| Fraxinus angustifolia Vahl subsp. angustifolia | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Fraxinus anomala Torr. ex S. Watson | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Fraxinus floribunda Wall. | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Fraxinus ornus L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marshall | X | X | Tree | CR | Nearctic | |

| Ligustrum japonicum Thunb. | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Ligustrum lucidum W.T. Aiton | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental |

| Ligustrum sinense Lour. | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Olea capensis L. | X | Tree | NE | Afrotropical | ||

| Olea europaea L. subsp. europaea | X | X | X | Tree | DD | Palearctic |

| Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata (Wall. and G.Don) Cif. | X | Tree | NE | Afrotropical—Palearctic | ||

| Osmanthus fragrans Lour. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Phillyrea latifolia L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Picconia azorica (Tutin) Knobl. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Picconia excelsa (Aiton) DC. | X | Tree | VU | Afrotropical | ||

| Syringa vulgaris L. | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic |

| Paulowniaceae | ||||||

| Paulownia tomentosa (Thunb.) Steud. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic |

| Phyllanthaceae | ||||||

| Phyllanthus juglandifolius Willd. | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Andean—Neotropical | ||

| Phytolaccaceae | ||||||

| Phytolacca dioica L. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Andean—Neotropical |

| Pinaceae | ||||||

| Abies concolor (Gordon and Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Abies pinsapo Boiss. | X | Tree | EN | Palearctic | ||

| Cedrus atlantica (Endl.) Manetti ex Carrière | X | X | Tree | EN | Palearctic | |

| Cedrus deodara (Roxb. ex D.Don) G.Don | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Picea laxa (Münchh.) Sarg. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Picea pungens Engelm. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Pinus bungeana Zucc. ex Endl. | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Pinus canariensis C.Sm. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical | ||

| Pinus halepensis Mill. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Pinus nigra J.F.Arnold | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Pinus pinea L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Pinus sylvestris L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Pinus teocote Schiede ex Schltdl. and Cham. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Pinus torreyana Parry ex Carrière | X | Tree | CR | Nearctic | ||

| Piperaceae | ||||||

| Piper jacquemontianum Kunth | X | Shrub | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Pittosporaceae | ||||||

| Pittosporum crassifolium Banks and Sol. ex A.Cunn. | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neozelandic | ||

| Pittosporum tobira (Thunb.) W.T.Aiton | X | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Oriental—Palearctic |

| Pittosporum undulatum Vent. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate |

| Pittosporum viridiflorum Sims | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Afrotropical | ||

| Platanaceae | ||||||

| Platanus × hispanica Mill. ex Münchh. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Hybrid |

| Podocarpaceae | ||||||

| Afrocarpus mannii (Hook.f.) C.N.Page | X | X | X | Tree | VU | Afrotropical |

| Podocarpus macrophyllus (Thunb.) Sweet | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Podocarpus neriifolius D.Don | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Podocarpus totara G.Benn. ex D.Don | X | Tree | LC | Neozelandic | ||

| Primulaceae | ||||||

| Myrsine africana L. | X | Shrub | NE | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate—Oriental | ||

| Proteaceae | ||||||

| Banksia integrifolia L.f. | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate | |

| Grevillea olivacea A.S.George | X | Shrub | LC | Australotropical | ||

| Grevillea robusta A.Cunn. ex R.Br. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Australotemperate |

| Grevillea thelemanniana Hügel ex Lindl. | X | Shrub | NE | Australotropical | ||

| Hakea laurina R.Br. | X | Shrub or Tree | VU | Australotemperate | ||

| Macadamia integrifolia Maiden and Betche | X | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | |

| Macadamia ternifolia F. Muell. | X | Tree | EN | Australotemperate | ||

| Quillajaceae | ||||||

| Quillaja lancifolia D.Don | X | Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Rhamnaceae | ||||||

| Colletia paradoxa (Spreng.) Escal. | X | Shrub | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Colletia spinosissima J.F.Gmel. | X | Shrub | LC | Andean—Neotropical | ||

| Fontanesia fortunei Carrière | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Frangula azorica Grubov | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Hovenia dulcis Thunb. | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Noltea africana (L.) Rchb. f. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Afrotemperate | ||

| Paliurus spina-christi Mill. | X | Shrub | NE | Palearctic | ||

| Pomaderris apetala Labill. | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neozelandic | ||

| Rhamnus alaternus L. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic | |

| Rhamnus cathartica L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Ziziphus jujuba Mill. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Rosaceae | ||||||

| Cotoneaster coriaceus Franch. | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic |

| Crataegus azarolus L. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Crataegus monogyna Jacq. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Palearctic | |

| Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl. | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh. | X | Shrub or Tree | EN | Palearctic | ||

| Phoenix sylvestris (L.) Roxb. | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Photinia serratifolia (Desf.) Kalkman | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Prunus avium (L.) L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Prunus azorica (hort. ex Mouill) Rivas Mart., Lousã, Fern. Prieto, J.C. Costa and C. Aguiar | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic | ||

| Prunus caroliniana (Mill.) Aiton | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. subsp. cerasifera | X | X | X | Tree | DD | Palearctic |

| Prunus laurocerasus L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Prunus lusitanica L. | X | X | Tree | EN | Palearctic | |

| Prunus persica (L.) Batsch | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Palearctic | |

| Prunus × blireana André | X | X | Tree | NE | Hybrid | |

| Pyracantha angustifolia (Franch.) C.K.Schneid. | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Pyracantha crenulata (D.Don) M.Roem. | X | Shrub | NE | Oriental | ||

| Pyrus pyrifolia (Burm. f.) Nakai | X | Tree | NE | Oriental | ||

| Rhaphiolepis indica (L.) Lindl. | X | X | X | Shrub | NE | Oriental |

| Spiraea cantoniensis Lour. | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Oriental |

| Stranvaesia nussia (Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don) | X | Tree | NE | Oriental—Palearctic | ||

| Rubiaceae | ||||||

| Coffea arabica L. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | EN | Afrotropical | |

| Coffea racemosa Lour. | X | Shrub or Tree | NT | Afrotropical | ||

| Coprosma repens A.Rich. | X | X | Shrub | NE | Neozelandic | |

| Gardenia thunbergia Thunb. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | |

| Rogiera amoena Planch. | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Rogiera backhousii (Hook.f.) Borhidi | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Rutaceae | ||||||

| Calodendrum capense (L.f.) Thunb. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Casimiroa edulis La Llave | X | Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Citrus × aurantium L. | X | X | Tree | NE | Hybrid | |

| Citrus glauca (Lindl.) Burkill | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Citrus trifoliata L. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Citrus × limon (L.) Osbeck | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Hybrid | |

| Pilocarpus pennatifolius Lem. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical | |

| Zanthoxylum armatum DC. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Oriental | |

| Salicaceae | ||||||

| Dovyalis caffra (Hook.f. and Harv.) Warb. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate |

| Populus alba L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Populus nigra L. | X | X | Tree | DD | Palearctic | |

| Salix × pendulina f. salamonii (Carrière) I.V.Belyaeva | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Hybrid | ||

| Salix atrocinerea Brot. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Sapindaceae | ||||||

| Acer campestre L. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Acer granatense Boiss. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Acer monspessulanum L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Acer negundo L. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Acer palmatum Thunb. | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Acer pseudoplatanus L. | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Aesculus glabra Willd. | X | Tree | LC | Nearctic | ||

| Aesculus hippocastanum L. | X | X | Tree | VU | Palearctic | |

| Aesculus × carnea Zeyh. | X | X | X | Tree | NE | Hybrid |

| Dodonaea viscosa Jacq. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Australotemperate—Australotropical—Neoguinean—Neotropical—Neozelandic—Oriental | |

| Harpullia pendula Planch. ex F.Muell. | X | Tree | NE | Australotemperate | ||

| Hippobromus pauciflorus (L.f.) Radlk. | X | Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Koelreuteria bipinnata Franch. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Oriental | |

| Koelreuteria paniculata Laxm. | X | X | Tree | LC | Oriental—Palearctic | |

| Sapindus drummondii Hook. and Arn. | X | X | Tree | NE | Nearctic | |

| Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn. | X | X | Tree | NE | Oriental—Palearctic | |

| Sapindus saponaria L. | X | Tree | LC | Oriental | ||

| Sapotaceae | ||||||

| Chrysophyllum imperiale (Linden ex K.Koch and Fintelm.) Benth. and Hook.f. | X | X | Tree | EN | Neotropical | |

| Sideroxylon inerme L. | X | Tree | NE | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Sideroxylon mirmulano R.Br. | X | Tree | EN | Afrotropical | ||

| Scrophulariaceae | ||||||

| Myoporum laetum G.Forst. | X | X | Tree | NE | Neozelandic | |

| Simaroubaceae | ||||||

| Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | X | X | Tree | NE | Palearctic | |

| Solanaceae | ||||||

| Brugmansia aurea Lagerh. | X | Shrub | EW | Neotropical | ||

| Cestrum × cultum Francey | X | Shrub | NE | Hybrid | ||

| Nicotiana glauca Graham | X | Shrub | NE | Andean—Neotropical | ||

| Solanum crinitum Lam. | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Stilbaceae | ||||||

| Halleria lucida L. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Afrotropical—Afrotemperate | ||

| Tamaricaceae | ||||||

| Tamarix africana Poir. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Tamarix gallica L. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Tamarix parviflora DC. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | ||

| Taxaceae | ||||||

| Cephalotaxus harringtonia (Knight ex J.Forbes) K.Koch | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Oriental | |

| Taxus baccata L. | X | X | X | Tree | LC | Palearctic |

| Torreya californica Torr. | X | Tree | VU | Nearctic | ||

| Theaceae | ||||||

| Camellia japonica L. | X | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic | |

| Ulmaceae | ||||||

| Ulmus minor Mill. | X | Tree | DD | Palearctic | ||

| Zelkova serrata (Thunb.) Makino | X | X | Tree | NT | Oriental—Palearctic | |

| Urticaceae | ||||||

| Myriocarpa longipes Liebm. | X | Shrub or Tree | NE | Neotropical | ||

| Verbenaceae | ||||||

| Citharexylum spinosum L. | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Neotropical | ||

| Duranta erecta L. | X | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Nearctic—Neotropical |

| Viburnaceae | ||||||

| Sambucus nigra L. | X | X | Shrub or Tree | LC | Palearctic | |

| Viburnum odoratissimum Ker Gawl. | X | Shrub | LC | Oriental | ||

| Viburnum rhytidophyllum Hemsl. | X | Shrub | NE | Oriental | ||

| Viburnum tinus L. | X | X | X | Shrub | LC | Palearctic |

| Xanthorrhoeaceae | ||||||

| Kumara plicatilis (L.) G.D.Rowley | X | Rosette tree | NE | Afrotemperate |

| Characteristics | JBA | JBL | JBT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of creation | 1764 | 1837 | 1906 |

| Year of inauguration | 1768 | 1878 | 1914 * |

| Location | western Lisbon/Ajuda | Central Lisbon | western Lisbon/Belém |

| Coordinates (latitude/longitude) | 38.706205/−9.199421 | 38.717429/−9.150306 | 38.698140/−9.203913 |

| Elevation | 70–80 m | 37–77 m | 10–35 m |

| Area (green spaces) | 3.8 ha | 5.6 ha | 6.4 ha |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunha, A.R.; Soares, A.L.; Brilhante, M.; Arsénio, P.; Vasconcelos, T.; Espírito-Santo, D.; Duarte, M.C.; Romeiras, M.M. Natural and Historical Heritage of the Lisbon Botanical Gardens: An Integrative Approach with Tree Collections. Plants 2021, 10, 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10071367

Cunha AR, Soares AL, Brilhante M, Arsénio P, Vasconcelos T, Espírito-Santo D, Duarte MC, Romeiras MM. Natural and Historical Heritage of the Lisbon Botanical Gardens: An Integrative Approach with Tree Collections. Plants. 2021; 10(7):1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10071367

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha, Ana Raquel, Ana Luísa Soares, Miguel Brilhante, Pedro Arsénio, Teresa Vasconcelos, Dalila Espírito-Santo, Maria Cristina Duarte, and Maria Manuel Romeiras. 2021. "Natural and Historical Heritage of the Lisbon Botanical Gardens: An Integrative Approach with Tree Collections" Plants 10, no. 7: 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10071367

APA StyleCunha, A. R., Soares, A. L., Brilhante, M., Arsénio, P., Vasconcelos, T., Espírito-Santo, D., Duarte, M. C., & Romeiras, M. M. (2021). Natural and Historical Heritage of the Lisbon Botanical Gardens: An Integrative Approach with Tree Collections. Plants, 10(7), 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10071367