Broomrape Species Parasitizing Odontarrhena lesbiaca (Brassicaceae) Individuals Act as Nickel Hyperaccumulators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

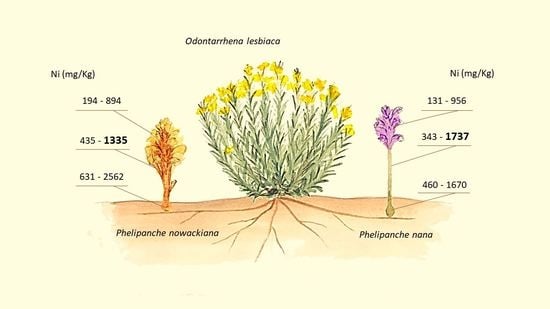

2.1. Broomrape Species Recorded

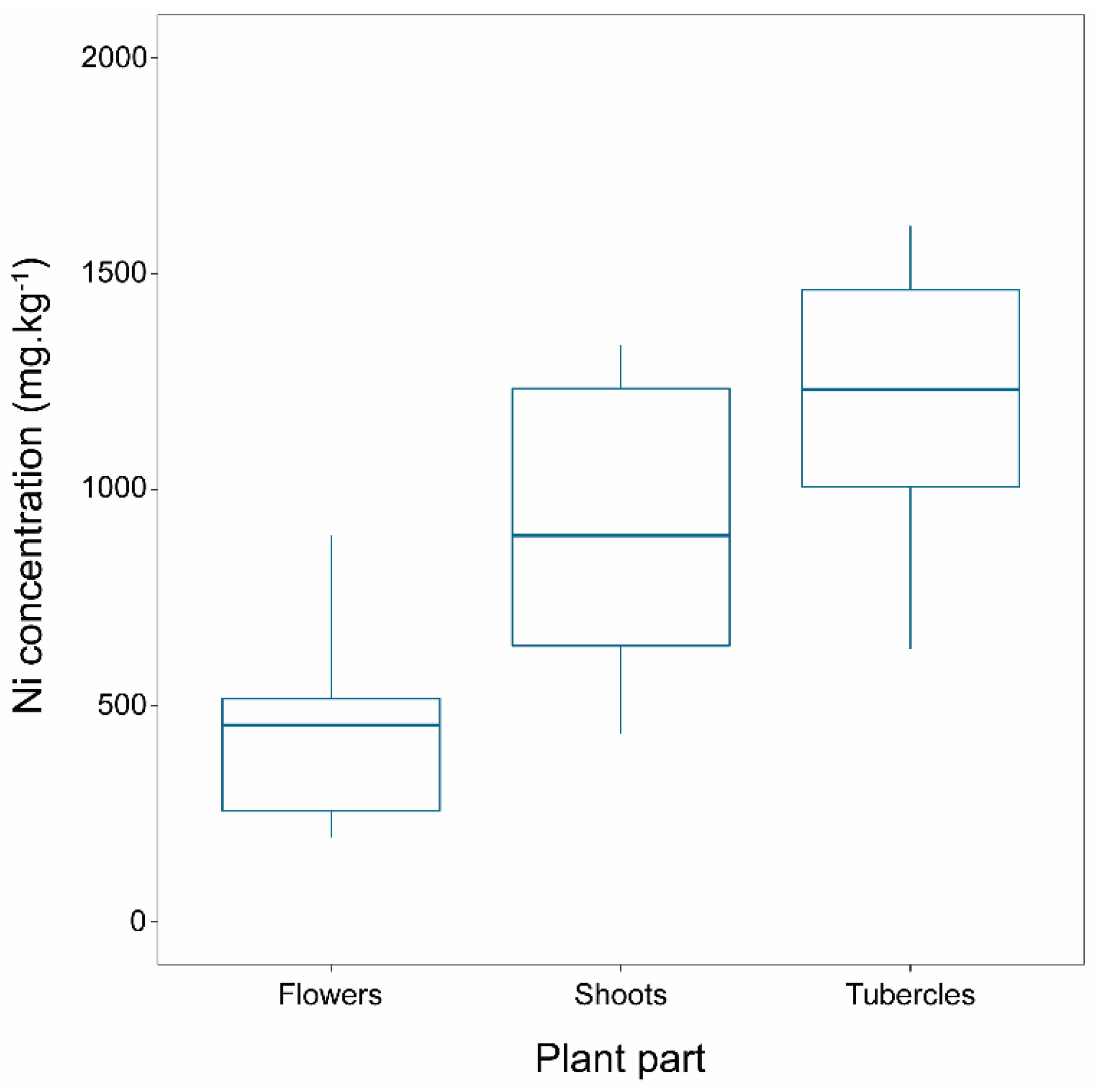

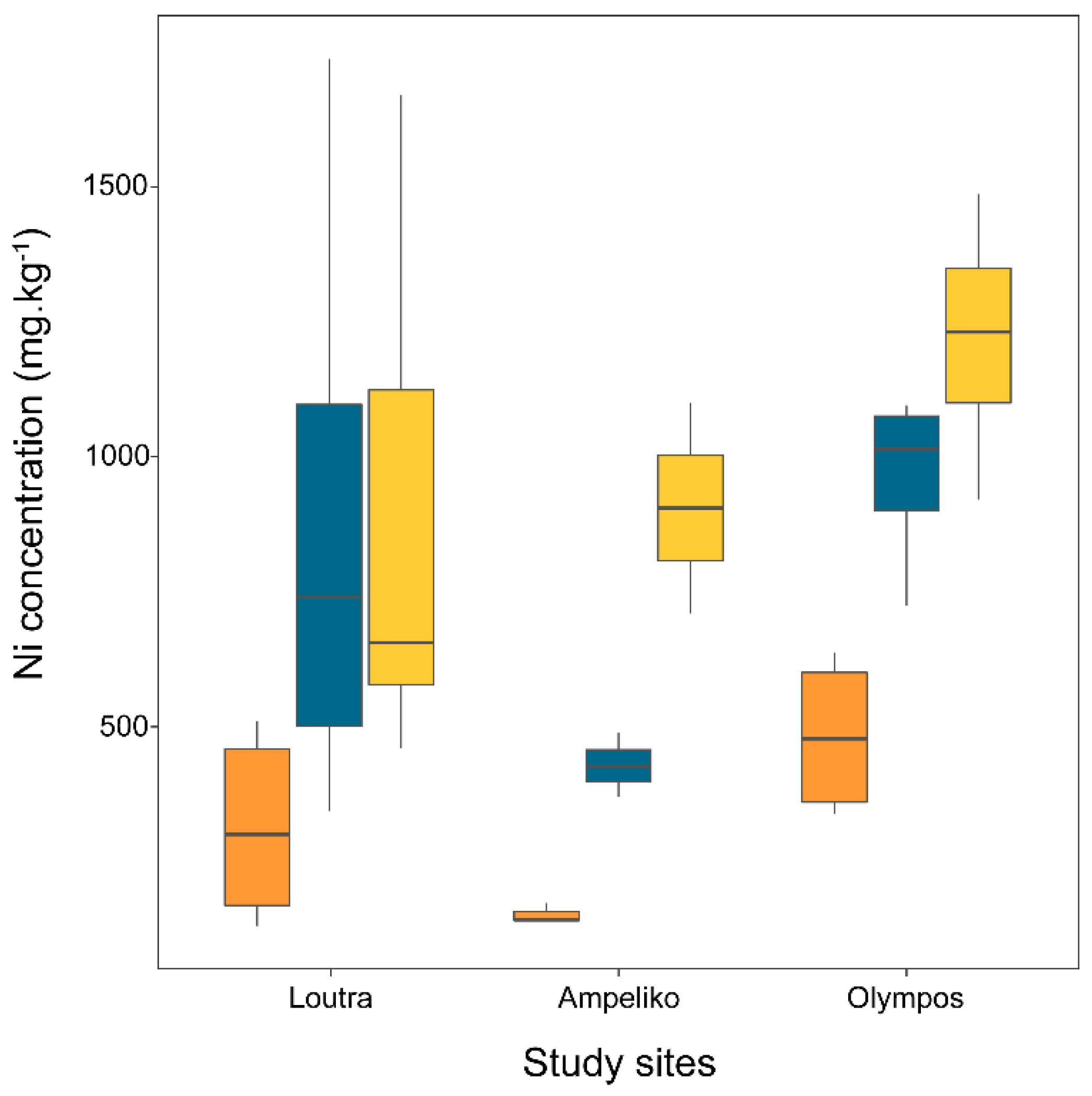

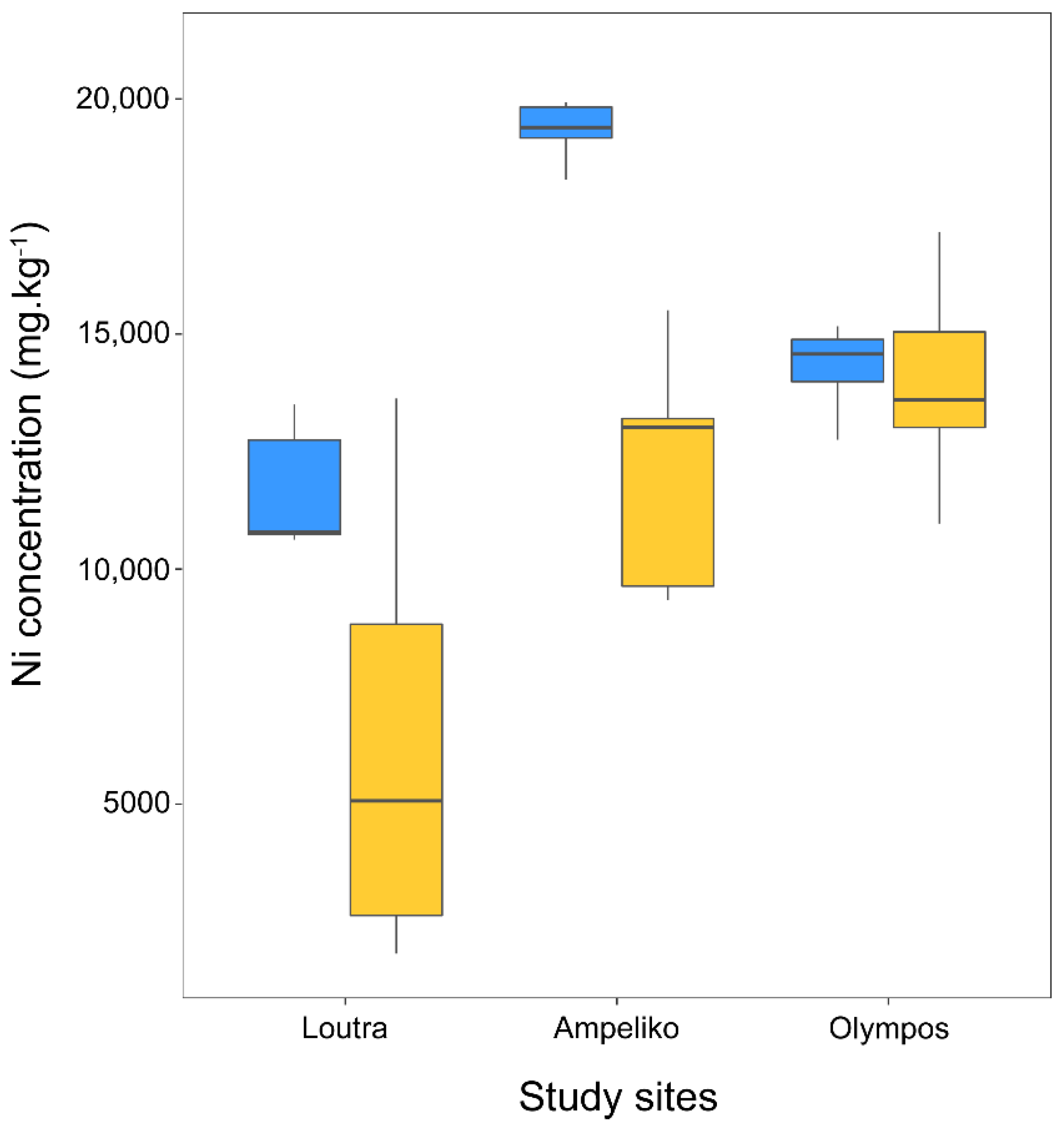

2.2. Ni Concentration in Broomrape Species

2.3. O. lesbiaca—Broomrape Species Complex

2.4. Effects of Broomrapes on Leaf Nickel Concentration of O. lesbiaca

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area and Species

4.2. Plant Sampling

4.3. Ni Determination in Plant and Soil Samples

4.4. Data Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, D.C.; Douglas, A.E. The Biology of Symbiosis; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Delavault, P.; Montiel, G.; Brun, G.; Pouvreau, J.B.; Thoiron, S.; Simier, P. Communication between host plants and parasitic plants. In How Plants Communicate with Their Biotic Environment; Becard, G., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, L.J.; Cameron, D.D. You are what you eat: Interactions between root parasitic plants and their hosts. Adv. Bot. Res. 2009, 50, 87–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, I. How Striga parasitizes its host: A TEM and SEM study. Ann. Bot. 1997, 79, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, N.M.; Dörr, I.; Hansen, M.; van der Kooij, T.A.W.; Schulz, A. Development of Cuscuta species on a partially incompatible host: Induction of xylem transfer cells. Protoplasma 2003, 220, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, K.U.; Cameron, D.D. The anatomy of Santalum album (sandalwood) haustoria. Can. J. Bot. 2006, 84, 1608–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Smith, R.S.; Shiel, R.S.; Peacock, S.; Simkin, J.M.; Quirk, H.; Hobbs, P.J. Parasitic plants indirectly regulate belowground properties in grassland ecosystems. Nature 2006, 439, 969–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Těšitel, J.; Mládek, J.; Horník, J.; Těšitelová, T.; Adamec, V.; Tichý, L. Suppressing competitive dominants and community restoration with native parasitic plants using the hemiparasitic Rhinanthus alectorolophus and the dominant grass Calamagrostis epigejos. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, J.H.; Yoder, J.I.; Timko, M.P.; dePamphilis, C.W. The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubiales, D.; Heide-Jørgensen, H.S. Parasitic Plants. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (eLS); John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.R.; Mathews, S. Phylogeny of the parasitic plant family Orobanchaceae inferred from phytochrome A. Am. J. Bot. 2006, 93, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joel, D.M. The new nomenclature of Orobanche and Phelipanche. Weed Res. 2009, 49, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, D.C.; Beardsley, P.M.; Kelchner, S.A.; Olmstead, R.G. Review of the systematics of Scrophulariaceae s.l. and their current disposition. Aust. Syst. Bot. 2006, 19, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.K. Biocontrol. In Parasitic Orobanchaceae; Joel, D.M., Gressel, J., Musselman, L.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 469–497. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, A.C. Resurrection of the genus Aphyllon for New World broomrapes (Orobanche s.l., Orobanchaceae). PhytoKeys 2016, 75, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.R. Serpentine and its Vegetation: A Multidisciplinary Approach; Dioscorides Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A.J.M.; Proctor, J.; van Balgooy, M.; Reeves, R. Hyperaccumulation of nickel by the flora of the ultramafics of Palawan, Republic of the Philippines. In The Vegetation of Ultramafic (Serpentine) Soils; Baker, A.J.M., Proctor, J., Reeves, R.D., Eds.; Intercept Ltd.: Andover, Hampshire, UK, 1992; pp. 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kruckeberg, A.R. Geology and Plant Life: The Effects of Landforms and Rock Type on Plants; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kazakou, E.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Baker, A.J.M.; Reeves, R.D.; Troumbis, A.Y. Hypotheses, mechanisms and trade-offs of tolerance and adaptation to serpentine soils: From species to ecosystem level. Biol. Rev. 2008, 83, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruckeberg, A.R. The ecology of serpentine soils. III. Plant species in relation to serpentine soils. Ecology 1954, 35, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, J.; Woodell, S.R.J. The ecology of serpentine soils. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1975, 9, 255–366. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, R.D.; van der Ent, A.; Echevarria, G.; Isnard, S.; Baker, A.J.M. Global Distribution and Ecology of Hyperaccumulator Plants. In Agromining: Farming for Metals; Mineral Resource Reviews; van der Ent, A., Baker, A.J., Echevarria, G., Simonnot, M.O., Morel, J.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R.D. The hyperaccumulation of nickel by serpentine plants. In The Vegetation of Ultramafic (Serpentine) Soils; Baker, A.J.M., Proctor, J., Reeves, R.D., Eds.; Intercept Ltd.: Andover, Hampshire, UK, 1992; pp. 253–277. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ent, A.; Baker, A.J.M.; Reeves, R.D.; Pollard, A.J.; Schat, H. Hyperaccumulators of metal and metalloid trace elements: Facts and fiction. Plant Soil 2013, 362, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ent, A.; Echevarria, G.; Nkrumah, P.N.; Erskine, P.D. Frequency distribution of foliar nickel is bimodal in the ultramafic flora of Kinabalu Park (Sabah, Malaysia). Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, R.D.; Baker, A.J.M.; Becquer, T.; Echevarria, G.; Miranda, Z. The flora and biogeochemistry of the ultramafic soils of Goiás state, Brazil. Plant Soil 2007, 293, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani, A.; Pavlova, D.; Garrido-Rodríguez, B.; Kidd, P.S.; Prieto-Fernandez, A.; Konstantinou, M.; Kyrkas, D.; Morel, J.L.; Prieto-Fernandez, A.; Puschenreiter, M.; et al. Element Case Studies in the Temperate/Mediterranean Regions of Europe: Nickel. In Agromining: Farming for Metals; Mineral Resource Reviews; van der Ent, A., Baker, A.J., Echevarria, G., Simonnot, M.O., Morel, J.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strid, A.; Tan, K. Flora Hellenica; A.R.G. Gantner Verlag KG: Ruggell, Liechtenstein, 2002; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Adamidis, G.C.; Aloupi, M.; Kazakou, E.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. Intra-specific variation in Ni tolerance, accumulation and translocation patterns in the Ni-hyperaccumulator Alyssum lesbiacum. Chemosphere 2014, 95, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.R.; Morrison, R.S.; Reeves, R.D.; Dudley, T.R.; Akman, Y. Hyperaccumulation of nickel by Alyssum Linnaeus (Cruciferae). Proc. Royal Soc. Lond. B 1979, 203, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakou, E.; Adamidis, G.C.; Baker, A.J.M.; Reeves, R.D.; Godino, M.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. Species adaptation in serpentine soils in Lesbos Island (Greece): Metal hyperaccumulation and tolerance. Plant Soil 2010, 332, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamidis, G.C.; Aloupi, M.; Mastoras, P.; Papadaki, M.-I.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. Is annual or perennial harvesting more efficient in Ni phytoextraction? Plant Soil 2017, 418, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanatou, A.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Aloupi, M.; Adamidis, G.C.; Nakas, G.; Petanidou, T. From bioaccumulation to biodecumulation: Nickel movement from Odontarrhena lesbiaca (Brassicaceae) individuals into consumers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 747, 141197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigl, G.; Varga, V.; Molnár, Á.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Kolbert, Z. Different Nitro-Oxidative Response of Odontarrhena lesbiaca Plants from Geographically Separated Habitats to Excess Nickel. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.S.; Martens, S. The raison d’etre of metal hyperaccumulation by plants. In The Vegetation of Ultramafic (Serpentine) Soils; Baker, A.J.M., Proctor, J., Reeves, R.D., Eds.; Intercept Ltd.: Andover, Hampshire, UK, 1992; pp. 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, R.S. Plant defense using toxic inorganic ions: Conceptual models of the defensive enhancement and joint effects hypotheses. Plant Sci. J. 2012, 195, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, B.; Lindblom, S.; Loeffler, M.; Pilon-Smits, E. Selenium protects plants from phloem-feeding aphids due to both deterrence and toxicity. New Phytol. 2004, 162, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.S.; Jhee, E. A test of elemental defence against slugs by Ni in hyperaccumulator and non-hyperaccumulator Streptanthus species. Chemoecology 2005, 15, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.S.; Shaw, J.; Martens, S. Nickel hyperaccumulation defends Streptanthus polygaloides (Brassicaceae) against pathogens. Am. J. Bot. 1994, 81, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörger, A.C.; Fones, H.N.; Preston, G.M. The current status of the elemental defense hypothesis in relation to pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.S. The defense hypothesis of elemental hyperaccumulation: Status, challenges and new directions. Plant Soil 2007, 293, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesk, P.; Reichman, S. Hyperaccumulators and herbivores: A Bayesian meta-analysis of feeding choice trials. J. Chem. Ecol. 2009, 35, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.S.; Martens, N.S.; Davis, M.A. The nickel hyperaccumulator Streptanthus polygaloides (Brassicaceae) is attacked by the parasitic plant Cuscuta californica (Cuscutaceae). Madroño 1999, 46, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bani, A.; Pavlova, D.; Benizri, E.; Shallari, S.; Miho, L.; Meco, M.; Shahu, E.; Reeves, R.; Echevarria, G. Relationship between the Ni hyperaccumulator Alyssum murale and the parasitic plant Orobanche nowackiana from serpentines in Albania. Ecol. Res. 2018, 33, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, J.R. Review of recent taxonomic work on European serpentinicolous phanerogams. In The Vegetation of Ultramafic (Serpentine) Soils; Baker, A.J.M., Proctor, J., Reeves, R.D., Eds.; Intercept Ltd.: Andover, Hampshire, UK, 1992; pp. 435–449. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, M.J.Y. The taxonomic position of Orobanche rechingeri Gilli (Orobanchaceae) in relation to Orobanche nowackiana Markgr. Candollea 2000, 55, 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Von Raab-Straube, E.; Raus, T.; Bazos, I.; Cornec, J.P.; de Bélair, G.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; El Mokni, R.; Fateryga, A.V.; Fateryga, V.V.; Fridlender, A.; et al. Euro+Med-Checklist Notulae, 11. Willdenowia 2019, 49, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, A.; Fanigliulo, A.; Fontana, A.; Fascetti, S. First report of Orobanche nana on celery in Italy. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, D.; Bani, A. Pollen biology of the serpentine-endemic Orobanche nowackiana (Orobanchaceae) from Albania. Aust. J. Bot. 2019, 67, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.-H.-B.; van der Ent, A.; Tang, Y.-T.; Sterckeman, T.; Echevarria, G.; Morel, J.-L.; Qiu, R.-L. Nickel hyperaccumulation mechanisms: A review on the current state of knowledge. Plant Soil 2018, 423, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.; Ruyter-Spira, C.; Bouwmeester, H.J. Strigolactones and root infestation by plant-parasitic Striga, Orobanche and Phelipanche spp. Plant Sci. 2011, 180, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, U.; Cotter-Howells, J.D.; Charnock, J.M.; Baker, A.J.M.; Smith, J.A.C. Free histidine as a metal chelator in plants that hyperaccumulate nickel. Nature 1996, 379, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Ye, W.; Hong, L.; Huang, H.; Wang, Z.; Deng, X.; Yang, Q.; Xu, Z. Progress in parasitic plant biology: Host selection and nutrient transfer. Plant Biol. 2006, 8, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamidis, G.C.; Kazakou, E.; Baker, A.J.M.; Reeves, R.D.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. The effect of harsh abiotic conditions on the diversity of serpentine plant communities on Lesbos Island, an eastern Mediterranean island. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2014, 7, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamidis, G.C.; Kazakou, E.; Aloupi, M.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. Is it worth hyperaccumulating Ni on non-serpentine soils? Decomposition dynamics of mixed-species litters containing hyperaccumulated Ni across serpentine and non-serpentine environments. Ann. Bot. 2016, 117, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafranchis, T.; Sfikas, G. Flowers of Greece; 2-Volume Set; Diatheo: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thorogood, C. Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Eastern Mediterranean; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Richmond, Surrey, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA [United States Environmental Protection Agency]. Method 3052. Microwave Assisted Acid Digestion of Siliceous and Organically Based Matrices. 1996. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/3052.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- NEPM [National Environment Protection (Assessment of Site Contamination) Measure]. Schedule B3—Guideline on Laboratory Analysis of Potentially. Contaminated Soils. 2011. Available online: http://www.nepc.gov.au/system/files/resources/93ae0e77-e697-e494-656f-afaaf9fb4277/files/schedule-b3-guideline-laboratory-analysis-potentially-contaminated-soils-sep10.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Pate, J.S. Mineral relationships of parasites and their hosts. In Parasitic Plants; Press, M.C., Graves, J.D., Eds.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1995; pp. 80–102. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Loutra | Ampeliko | Olympos | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Min | Max | Mean | SE | Min | Max | Mean | SE | Min | Max | ||

| P. nana | Flower | 378 | 110 | 131 | 956 | 152 | 11 | 140 | 174 | 483 | 76 | 339 | 638 |

| Shoot | 859 | 191 | 343 | 1737 | 428 | 34 | 370 | 488 | 962 | 84 | 725 | 1095 | |

| Tubercle | 884 | 185 | 460 | 1670 | 906 | 196 | 710 | 1101 | 1218 | 119 | 921 | 1487 | |

| P. nowackiana | Flower | 481 | 85 | 194 | 894 | ||||||||

| Shoot | 937 | 116 | 435 | 1335 | |||||||||

| Tubercle | 1417 | 269 | 631 | 2562 | |||||||||

| O. pubescens1 | Flower | 15 | 5 | 8 | 25 | ||||||||

| Shoot | 9 | 1 | 7 | 11 | |||||||||

| Tubercle | 22 | 1 | 21 | 23 | |||||||||

| Ampeliko | Olympos | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broomrape Ni/O. lesbiaca Ni | Broomrape Ni/Soil Ni | Broomrape Ni/O. lesbiaca Ni | Broomrape Ni/Soil Ni | ||||||

| mean | SE | mean | SE | mean | SE | mean | SE | ||

| P. nana | Flower | 0.014 | 0.002 | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.012 | 0.176 | 0.047 |

| Stem | 0.039 | 0.004 | 0.114 | 0.007 | 0.057 | 0.005 | 0.313 | 0.060 | |

| Tubercle | 0.075 | 0.014 | 0.194 | 0.026 | 0.081 | 0.013 | 0.430 | 0.025 | |

| P. nowackiana | Flower | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.096 | 0.026 | ||||

| Stem | 0.073 | 0.027 | 0.243 | 0.069 | |||||

| Tubercle | 0.137 | 0.096 | 0.467 | 0.257 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Aloupi, M.; Tetradis, G.; Adamidis, G.C. Broomrape Species Parasitizing Odontarrhena lesbiaca (Brassicaceae) Individuals Act as Nickel Hyperaccumulators. Plants 2021, 10, 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10040816

Dimitrakopoulos PG, Aloupi M, Tetradis G, Adamidis GC. Broomrape Species Parasitizing Odontarrhena lesbiaca (Brassicaceae) Individuals Act as Nickel Hyperaccumulators. Plants. 2021; 10(4):816. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10040816

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitrakopoulos, Panayiotis G., Maria Aloupi, Georgios Tetradis, and George C. Adamidis. 2021. "Broomrape Species Parasitizing Odontarrhena lesbiaca (Brassicaceae) Individuals Act as Nickel Hyperaccumulators" Plants 10, no. 4: 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10040816

APA StyleDimitrakopoulos, P. G., Aloupi, M., Tetradis, G., & Adamidis, G. C. (2021). Broomrape Species Parasitizing Odontarrhena lesbiaca (Brassicaceae) Individuals Act as Nickel Hyperaccumulators. Plants, 10(4), 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10040816