Morphometric and Molecular Diversity among Seven European Isolates of Pratylenchus penetrans

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Morphometrical Observations

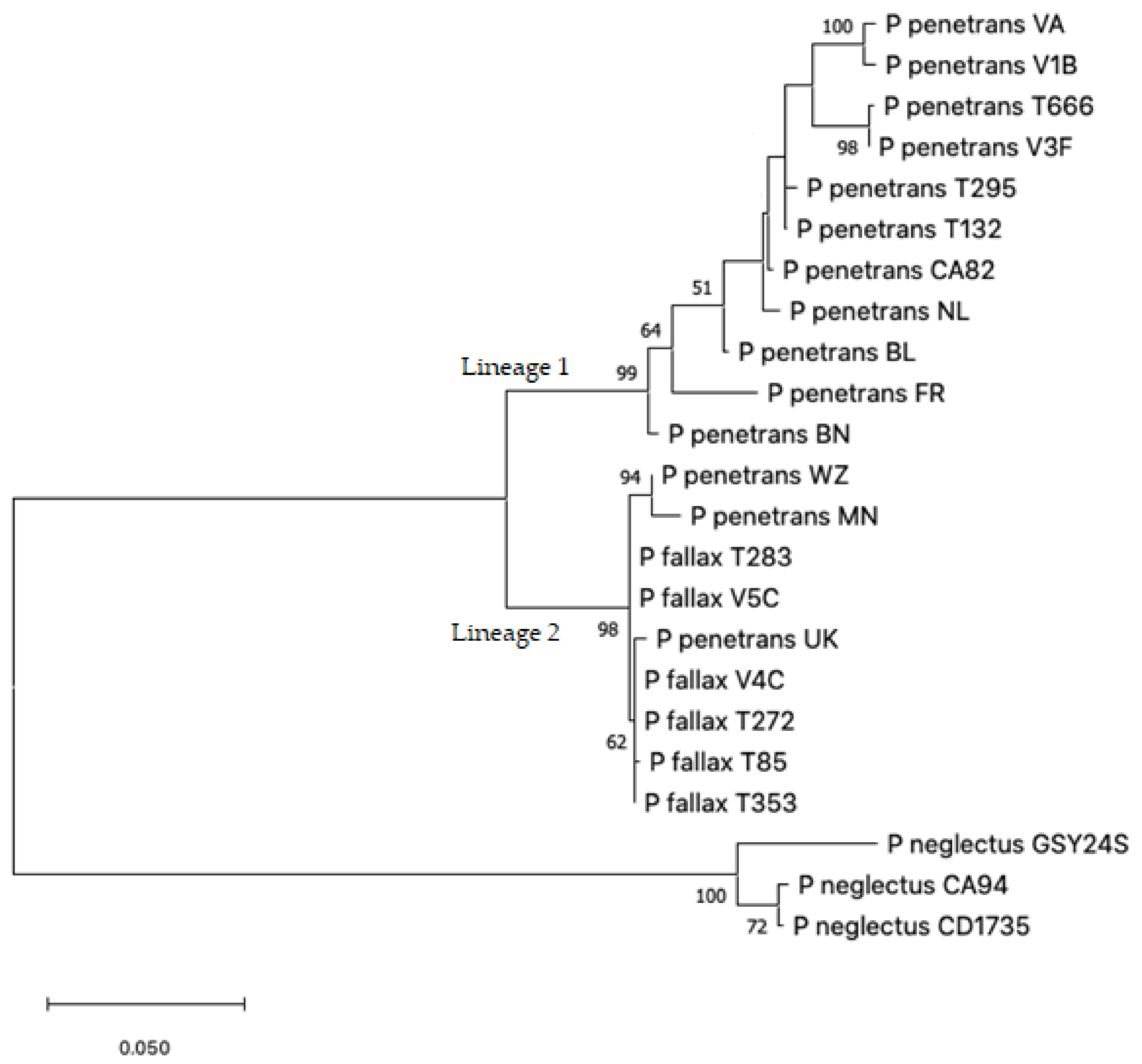

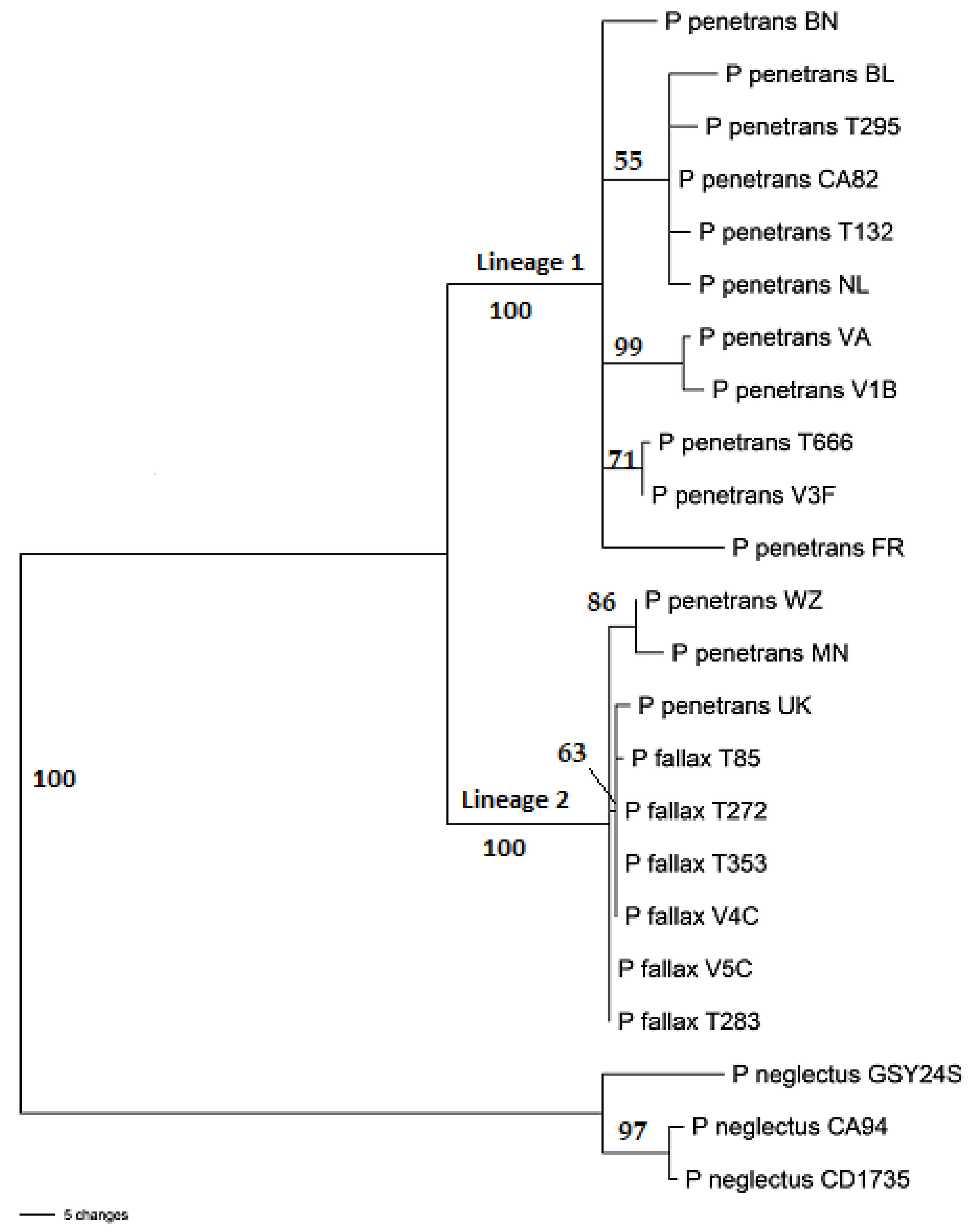

2.2. Nucleotide Sequence Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. Morphometrical Observations

3.2. Sequence Analysis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Nematode Isolates and Microscopy

4.2. DNA Extraction

4.3. Nucelotide Sequence Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castillo, P.; Vovlas, N. Pratylenchus (Nematoda: Pratylenchidae): Diagnosis, biology, pathogenicity and management. Nematol. Monogr. Perspect. 2007, 6, 1–543. [Google Scholar]

- Ryss, A. Genus Pratylenchus Filipjev (Nematoda: Tylenchida: Pratylenchidae): Multientry and monoentry keys and diagnostic relationships. Zoosyst. Ross. 2002, 10, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, M.; Jordana, R.; Goldaracena, A.; Pinochet, J. SEM observations of nine species of the genus Pratylenchus Filipjev, 1936 (Nematoda: Pratylenchidae). J. Nematode Morphol. Syst. 2001, 3, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, D.; Luc, M.; Manzanilla-Lopez, R. Identification, morphology and biology of plant-parasitic nematodes. In Plant-Parasitic Nematodes in Tropical Agriculture; Luc, M., Sikora, R., Bridge, J., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2005; pp. 11–52. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, J.; Hirschmann, H. Morphology and morphometrics of six species of Pratylenchus I. J. Nematol. 1969, 1, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Handoo, Z.A.; Carta, L.K.; Skantar, A.M. Taxonomy, morphology and phylogenetics of coffee-associated root-lesion nematodes, Pratylenchus spp. In Plant-Parasitic Nematodes of Coffee; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Seinhorst, J.W. Three new Pratylenchus species with a discussion of the structure of the cephalic framework and of the spermatheca in this genus. Nematologica 1968, 14, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarte, R.; Mai, W.F. Morphological variation in Pratylenchus penetrans. J. Nematol. 1976, 8, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perry, R.; Plowright, R.; Webb, R. Mating between Pratylenchus penetrans and P. fallax in sterile culture. Nematologica 1980, 26, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, S.K.; Perry, R.N.; Webb, R.M. Use of isoenzyme and protein phenotypes to discriminate between six Pratylenchus species from Great Britain. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1995, 126, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waeyenberge, L.; Ryss, A.; Moens, M.; Pinochet, J.; Vrain, T. Molecular characterisation of 18 Pratylenchus species using rDNA restriction fragment length polymorphism. Nematology 2000, 2, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troccoli, A.; Subbotin, S.; Chitambar, J.; Janssen, T.; Waeyenberge, L.; Stanley, J.; Duncan, L.; Agudelo, P.; Uribe, G.; Franco, J.; et al. Characterisation of amphimictic and parthenogenetic populations of Pratylenchus bolivianus Corbett, 1983 (Nematoda: Pratylenchidae) and their phylogenetic relationships with closely related species. Nematology 2016, 18, 651–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, T.; Karssen, G.; Orlando, V.; Subbotin, S.; Bert, W. Molecular characterization and species delimiting of plant-parasitic nematodes of the genus Pratylenchus from the penetrans group (Nematoda: Pratylenchidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017, 117, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, V.; Grove, I.G.; Edwards, S.G.; Prior, T.; Roberts, D.; Neilson, R.; Back, M. Root-lesion nematodes of potato: Current status of diagnostics, pathogenicity and management. Plant Pathol. 2020, 69, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Han, H.; Ryu, S.; Kim, W. Amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis and genetic variation of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in South Korea. Animal Cells Syst. 2010, 14, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, V.R.; Mattos, V.S.; Almeida, M.R.A.; Santos, M.F.A.; Tigano, M.S.; Castagnone-Sereno, P.; Carneiro, R.M.D.G. Genetic diversity of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne ethiopica and development of a species-specific SCAR marker for its diagnosis. Plant Pathol. 2014, 63, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Širca, S.; Stare, B.; Strajnar, P.; Urek, G. PCR-RFLP diagnostic method for identifying Globodera species in Slovenia. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2010, 49, 361–369. [Google Scholar]

- Pinochet, P.; Ceres, J.L.; Fern, C.; Doucet, M.; Marull, A.J. Reproductive fitness and random amplified polymorphic DNA variation among isolates of Pratylenchus vulnus. J. Nematol. 1994, 26, 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, M.; Burrows, P.; Wright, D. Genomic diversity between Radopholus similis populations from around the world detected by RAPD-PCR analysis. Nematologica 1996, 42, 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Fallas, G.A.; Hahn, M.L.; Fargette, M.; Burrows, P.R.; Sarah, J.L. Molecular and biochemical diversity among isolates of Radopholus spp. from different areas of the world. J. Nematol. 1996, 28, 422–430. [Google Scholar]

- Tigano, M.; De Siqueira, K.; Castagnone-Sereno, P.; Mulet, K.; Queiroz, P.; Dos Santos, M.; Teixeira, C.; Almeida, M.; Silva, J.; Carneiro, R. Genetic diversity of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne enterolobii and development of a SCAR marker for this guava-damaging species. Plant Pathol. 2010, 59, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.; Simões, M.J.; Gomes, P.; Barroso, C.; Pinho, D.; Conceição, L.; Fonseca, L.; Abrantes, I.; Pinheiro, M.; Egas, C. Assessment of the geographic origins of pinewood nematode isolates via single nucleotide polymorphism in effector genes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, F.; Reyes, A.; Veronico, P.; Di Vito, M.; Lamberti, F.; De Giorgi, C. Characterization of the (GAAA) microsatellite region in the plant parasitic nematode Meloidogyne artiellia. Gene 2002, 293, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, R.S.; Stetina, S.R.; Tonos, J.L.; Scheffler, J.A.; Scheffler, B.E. Microsatellites reveal genetic diversity in Rotylenchulus reniformis populations. J. Nematol. 2009, 41, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.L.; MacGuidwin, A.E. Lesion nematode disease. Available online: https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/disandpath/nematode/pdlessons/Pages/LesionNematode.aspx (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Fanelli, E.; Troccoli, A.; Capriglia, F.; Lucarelli, G.; Vovlas, N.; Greco, N.; De Luca, F. Sequence variation in ribosomal DNA and in the nuclear hsp90 gene of Pratylenchus penetrans (Nematoda: Pratylenchidae) populations and phylogenetic analysis. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 152, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbotin, S.A.; Ragsdale, E.J.; Mullens, T.; Roberts, P.A.; Mundo-Ocampo, M.; Baldwin, J.G. A phylogenetic framework for root lesion nematodes of the genus Pratylenchus (Nematoda): Evidence from 18S and D2-D3 expansion segments of 28S ribosomal RNA genes and morphological characters. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008, 48, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Loof, P. Taxonomic studies on the genus Pratylenchus (Nematoda). Tijdschr. Plantenziekten 1960, 66, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, M.; Clark, S.A. Surface features in the taxonomy of Pratylenchus species. Rev. Nematol. 1983, 6, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.Y.; Ni, H.F.; Yen, J.H.; Wu, W.S.; Tsay, T.T. Identification of root-lesion nematode Pratylenchus penetrans and P. loosi (Nematoda: Pratylenchidae) from strawberry and tea plantations in Taiwan. Plant Pathol. Bull. 2009, 18, 247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.Y.; Tsay, T.T.; Lin, Y.Y. Identification and biological study of Pratylenchus spp. isolated from the crops in Taiwan. Plant Pathol. Bull. 2002, 11, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mokrini, F.; Waeyenberge, L.; Viaene, N.; Andaloussi, F.A.; Moens, M. Diversity of root-lesion nematodes (Pratylenchus spp.) associated with wheat (Triticum aestivum and T. durum) in Morocco. Nematology 2016, 18, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarjan, A.; Frederick, J. Intraspecific morphological variation among populations of Pratylenchus brachyurus and P. coffeae. J. Nematol. 1978, 10, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tuyet, N.; Elsen, A.; Nhi, H.; De Waele, D. Morphological and morphometrical characterisation of ten Pratylenchus coffeae populations from Vietnam. Russ. J. Nematol. 2012, 20, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mekete, T.; Reynolds, K.; Lopez-Nicora, H.; Gray, M.; Niblack, T. Distribution and diversity of root-lession nematode (Pratylenchus spp.) associated with Miscanthus × giganteus and Panicum virgatum used for biofuels, and species identification in multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Nematology 2011, 13, 673–686. [Google Scholar]

- Waeyenberge, L.; Viaene, N.; Moens, M. Species-specific duplex PCR for the detection of Pratylenchus penetrans. Nematology 2009, 11, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betre, T. Studies on the Biological and Molecular Variation among Seven Isolates of Pratylenchus Penetrans from Different Geographical Locations in Europe; Justus Liebig University: Giessen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Hallmann, J.; Subbotin, S. Extraction, processing and detection of plant and soil nematodes. In Plant-Parasitic Nematodes in Tropical Agriculture; Luc, M., Sikora, R., Bridge, J., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2005; pp. 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Decraemer, W.; Hunt, D.J. Structure and classification. In Plant Nematology; Perry, R.N., Moens, M., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 3–39. ISBN 9781780641515. [Google Scholar]

- Core R Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. 2019, 2. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Holterman, M.; Karssen, G.; Van Den Elsen, S.; Van Megen, H.; Bakker, J.; Helder, J. Small subunit rDNA-based phylogeny of the Tylenchida sheds light on relationships among some high-impact plant-parasitic nematodes and the evolution of plant feeding. Am. Phytopath. Soc. 2009, 99, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, L.K.; Li, S. Improved 18S small subunit rDNA primers for problematic nematode amplification. J. Nematol. 2018, 50, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, G.B. Nematode Molecular Evolution; University of Nottingham: Nottingham, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, J.; Blair, D.; McManus, D.P. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1992, 54, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Park, Y.; Lee, J.; Buso, N. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools. Nucleic 2019, 47, W636–W641. [Google Scholar]

- Swofford, D.L. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), version 4.0b4a; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA-X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis accross computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, D.; Bull, J. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst. Biol. 1993, 42, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Char. | P. penetrans Isolates | CV 4 (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MN | WZ | BN | BL | UK | FR | NL | ||

| L | 449 ± 9.70 1 a2 (431–462) 3 | 437 ± 9.60 a (381–492) | 506 ± 10.30 bc (465–578) | 525 ± 10.50 c (443 ± 594) | 470 ± 10.00 ab (428–517) | 544 ± 10.70 c (505–625) | 527 ± 10.50 c (465–572) | 6.23 |

| a | 26.00 ± 0.25 ab (24.80–28.60) | 25.10 ± 0.25 a (22.20–28.90) | 27.50 ± 0.25 d (24.40–31.20) | 26.30 ± 0.25 bc (22.10–29.70) | 25.10 ± 0.25 a (22.20–27.30) | 27.70 ± 0.25 d (25.90–30.20) | 27.10 ± 0.25 cd (24.60–30.80) | 2.85 |

| b’ | 4.34 ± 0.08 a (5.84–9.22) | 4.38 ± 0.08 a (6.63–9.55) | 4.52 ± 0.08 ab (6.32–10.30) | 4.33 ± 0.08 a (5.62–8.44) | 4.85 ± 0.08 bc (6.45–9.23) | 4.98 ± 0.08 c (5.33 ± 9.17) | 4.87 ± 0.08 c (6.92–8.50) | 4.59 |

| c | 19.30 ± 0.35 bc (17.10–20.50) | 19.10 ± 0.35 bc (16.40 -21.10) | 17.20 ± 0.33 a (14.10–20.30) | 18.20 ± 0.34 ab (14.40–20.70) | 18.20 ± 0.34 ab (14.60–21.70) | 20.00 ± 0.35 c (16.90–23.30) | 18.40 ± 0.34 ab (16.00–21.00) | 5.06 |

| V | 79.2 ± 0.81 a (77.90–80.80) | 79.9 ± 0.82 a (78.60–81.90) | 79.70 ± 0.81 a (73.30–82.90) | 80.90 ± 0.82 a (76.80–85.90) | 78.80 ± 0.81 a (76.70–81.60) | 79.80 ± 0.81 a (77.30–82.70) | 79.60 ± 0.81 a (76.00–82.30) | 6.68 |

| Stylet | 15.10 ± 0.12 a (14.60–15.60) | 15.40 ± 0.12 abc (14.50–16.00) | 15.30 ± 0.12 ab (15.00–15.80) | 15.80 ± 0.12 c (15.10–16.80) | 15.70 ± 0.12 bc (15.20–16.40) | 15.30 ± 0.12 abc (15.00–16.20) | 15.20 ± 0.12 ab (14.60–15.60) | 2.40 |

| Ph-L | 104.00 ± 3.50 ab (89–115) | 100.00 ± 3.50 ab (90–112) | 112.00 ± 3.50 bc (97–133) | 121.00 ± 3.50 c (100–136) | 97.00 ± 3.50 a (95–111) | 111.00 ± 3.50 abc (90–161) | 108.00 ± 3.50 abc (98–119) | 9.20 |

| Ph-O | 37.60 ± 1.54 a (30.90–40.20) | 44.10 ± 1.67 bc (37.60–50.00) | 45.40 ± 1.69 bc (32.60–58.70) | 46.30 ± 1.71 c (35.90–52.00) | 37.30 ± 1.53 a (33.10–41.50) | 40.40 ± 1.60 abc (30.50–45.80) | 42.10 ± 1.63 abc (34.80–50.40) | 11.33 |

| EP | 70.60 ± 1.26 a (67.10–72.40) | 67.70 ± 1.23 a (58.60–72.60) | 76.40 ± 1.31 bc (70.50–83.30) | 81.80 ± 1.35 c (74.30–94.70) | 71.60 ± 1.27 ab (69.50–74.10) | 79.30 ± 1.33 c (68.20–84.30) | 78.00 ± 1.32 c (73.50–82.00) | 4.98 |

| MBW | 17.30 ± 0.38 a (16.00–18.00) | 17.40 ± 0.38 a (16.20–19.40) | 18.40 ± 0.39 ab (16.10–20.20) | 19.90 ± 0.41 b (17.40–23.40) | 18.70 ± 0.39 ab (17.80–20.00) | 19.70 ± 0.40 b (18.00–24.00) | 19.40 ± 0.40 b (16.60–21.20) | 6.30 |

| Ovary | 152 ± 8.40 a (134–174) | 182 ± 8.40 ab (155–218) | 172 ± 8.40 ab (137–242) | 191 ± 9.40 b (114–244) | 163 ± 8.40 ab (131–221) | 155 ± 8.80 ab (122–184) | 177 ± 8.40 ab (142–220) | 14.92 |

| PUS | 23.60 ± 1.04 a (18.50–29.30) | 20.50 ± 1.04 a (17.40–28.50) | 19.60 ± 1.04 a (15.60–26.90) | 23.10 ± 1.04 a (21.30–24.40) | 19.70 ± 1.04 a (17.20–23.70) | 20.70 ± 1.04 a (15.70–29.30) | 22.60 ± 1.04 a (18.60–26.70) | 14.59 |

| P | 14.70 ± 0.40 a (1.18–2.47) | 15.70 ± 0.40 a (1.06–1.72) | 17.80 ± 0.40 b (0.88–1.42) | 18.20 ± 0.40 b (1.14–1.55) | 17.90 ± 0.40 b (0.94–1.41) | 18.10 ± 0.40 b (0.83–1.45) | 17.90 ± 0.40 b (1.00–1.50) | 7.06 |

| V-A | 71.00 ± 2.29 ab (68.30–74.50) | 66.00 ± 2.21 a (59.80–73.30) | 71.30 ± 2.30 ab (64.70–80.60) | 75.20 ± 2.36 abc (64.90–93.00) | 77.40 ± 2.40 bc (65.50–96.5) | 85.20 ± 2.51 c (70.20–107.0) | 78.60 ± 2.41 bc (68.20–87.80) | 9.33 |

| Tail | 23.30 ± 0.74 a (22.00–25.40) | 22.80 ± 0.73 a (21.90–24.70) | 29.30 ± 0.83 b (26.40–33.4) | 29.00 ± 0.83 b (25.60–36.2) | 26.00 ± 0.78 ab (20.30–30.40) | 27.60 ± 0.81 b (23.70–31.60) | 28.70 ± 0.82 b (24.70–32.10) | 8.50 |

| Species | Strain/Voucher | Accession Number | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2-D3 | COXI | β-1,4-endoglucanase | |||

| P. penetrans | MN | MW720686 | MW742327 | MW737621 | This study |

| P. penetrans | WZ | MW720687 | MW742328 | MW737622 | This study |

| P. penetrans | BN | MW720688 | MW742329 | MW737623 | This study |

| P. penetrans | BL | MW720689 | MW742330 | MW737624 | This study |

| P. penetrans | UK | MW720690 | MW742331 | MW737625 | This study |

| P. penetrans | FR | MW720691 | MW742332 | MW737626 | This study |

| P. penetrans | NL | MW720692 | MW742333 | MW737627 | This study |

| P. penetrans | VA | MW720693 | MW742334 | MW737628 | This study |

| P. penetrans | T666 | KY828351 | KY816982 | − | [13] |

| P. penetrans | T295 | KY828352 | KY816991 | − | [13] |

| P. penetrans | CA82 | EU130859 | KY817022 | − | [27] |

| P. penetrans | T132 | KY828358 | KY817015 | − | [13] |

| P. penetrans | V3F | KY828346 | KY816940 | − | [13] |

| P. penetrans | V1B | KY828348 | KY816942 | − | [13] |

| P. fallax | V5C | KY828361 | KY816937 | − | [13] |

| P. fallax | T85 | KY828367 | KY817017 | − | [13] |

| P. fallax | T283 | KY828364 | KY816996 | − | [13] |

| P. fallax | T272 | KY828365 | KY816998 | − | [13] |

| P. fallax | T353 | KY828363 | KY816988 | − | [13] |

| P. fallax | V4C | KY828362 | KY816938 | − | [13] |

| P. neglectus | GSY24S | KY424315 | KX349423 | − | Unpublished |

| P. neglectus | CA94 | EU130854 | KU198941 | − | [27] |

| P. neglectus | CD1735 | KU198962 | KU198940 | − | [12] |

| Geographical Origin | Isolates | MN | WZ | BN | BL | UK | FR | NL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany (Münster) | MN | _ | ||||||

| Germany (Witzenhausen) | WZ | 169 | _ | |||||

| Germany (Bonn) | BN | 143 | 206 | _ | ||||

| Belgium | BL | 288 | 428 | 237 | _ | |||

| United Kingdom | UK | 693 | 861 | 712 | 493 | _ | ||

| France | FR | 616 | 704 | 501 | 366 | 650 | _ | |

| The Netherlands | NL | 129 | 128 | 127 | 159 | 594 | 499 | _ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bogale, M.; Tadesse, B.; Nuaima, R.H.; Honermeier, B.; Hallmann, J.; DiGennaro, P. Morphometric and Molecular Diversity among Seven European Isolates of Pratylenchus penetrans. Plants 2021, 10, 674. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10040674

Bogale M, Tadesse B, Nuaima RH, Honermeier B, Hallmann J, DiGennaro P. Morphometric and Molecular Diversity among Seven European Isolates of Pratylenchus penetrans. Plants. 2021; 10(4):674. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10040674

Chicago/Turabian StyleBogale, Mesfin, Betre Tadesse, Rasha Haj Nuaima, Bernd Honermeier, Johannes Hallmann, and Peter DiGennaro. 2021. "Morphometric and Molecular Diversity among Seven European Isolates of Pratylenchus penetrans" Plants 10, no. 4: 674. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10040674

APA StyleBogale, M., Tadesse, B., Nuaima, R. H., Honermeier, B., Hallmann, J., & DiGennaro, P. (2021). Morphometric and Molecular Diversity among Seven European Isolates of Pratylenchus penetrans. Plants, 10(4), 674. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10040674