Crude Citric Acid of Trichoderma asperellum: Tomato Growth Promotor and Suppressor of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fermentation Materials

2.2. Isolation of Cellulolytic Fungi

2.3. Culturing Conditions

2.4. Quantification of Organic Acid (OA)

2.4.1. Total OA Determination

2.4.2. Quantitation of OA using HPLC

2.5. Molecular Identification

2.6. The Potential Antagonism of Trichoderma Filtrate

2.7. Crude Citric Acid (CA) Against Seed Germination

2.8. Evaluation of Crude CA under Greenhouse

2.8.1. Wilt Disease Parameters

2.8.2. Investigated Parameters

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fungal Survey

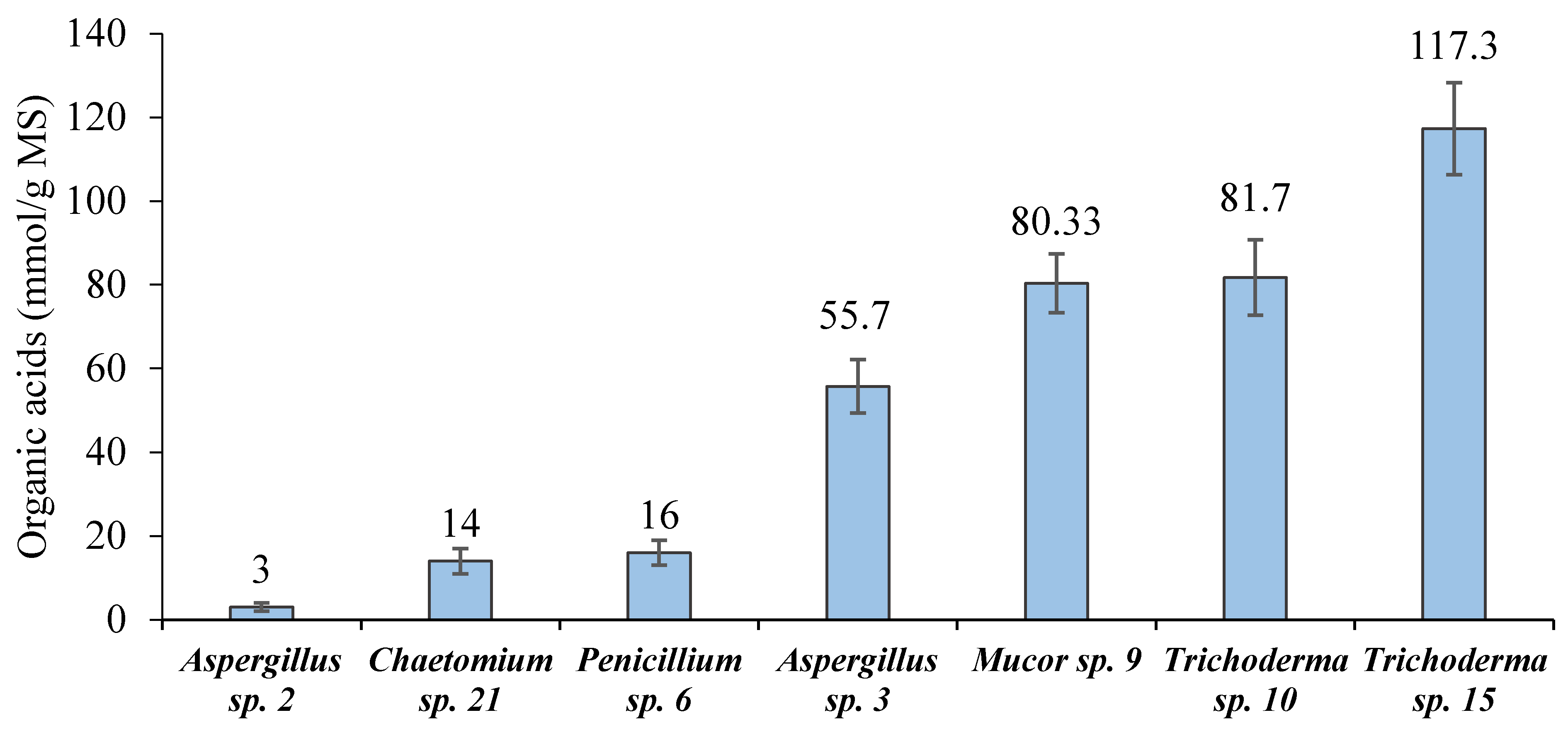

3.2. Screening of Cellulolytic Activity and OA Production

3.3. HPLC Screening of OA in the Hydrolysate of MS

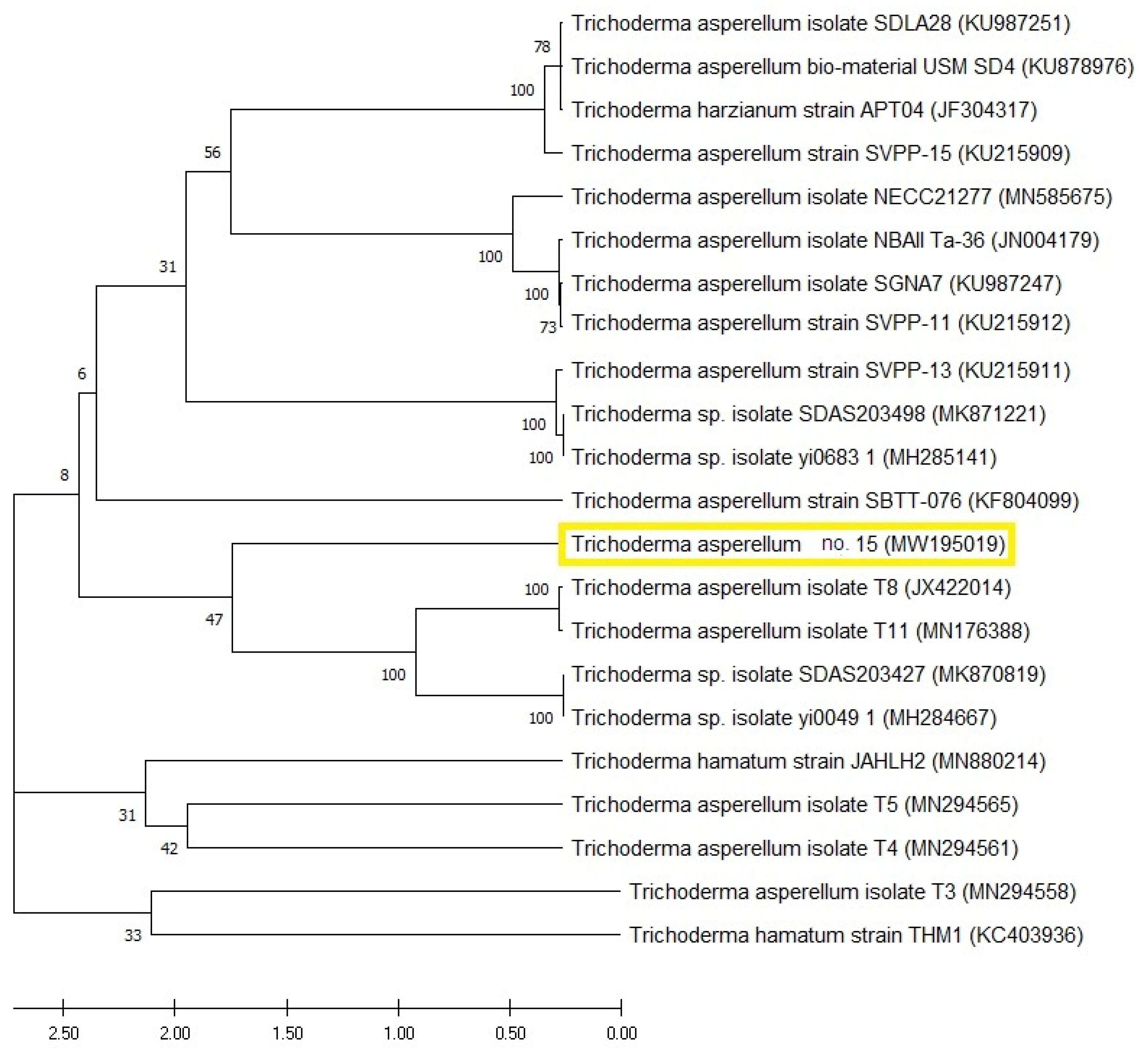

3.4. Molecular Identification’ of Trichoderma sp. 15

3.5. T. asperellum CA vs. F. oxysporum

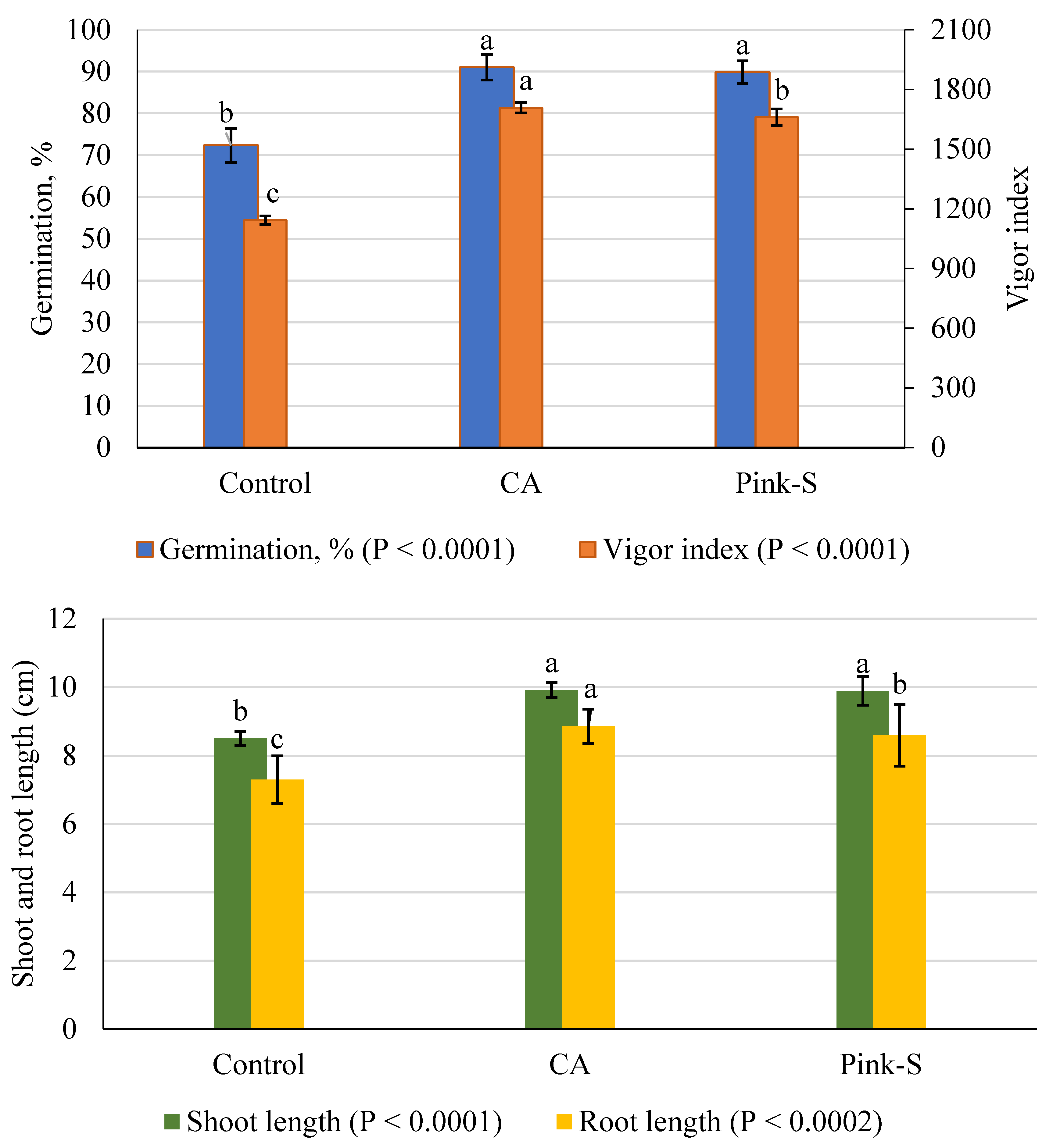

3.6. T. asperellum CA vs. Germination

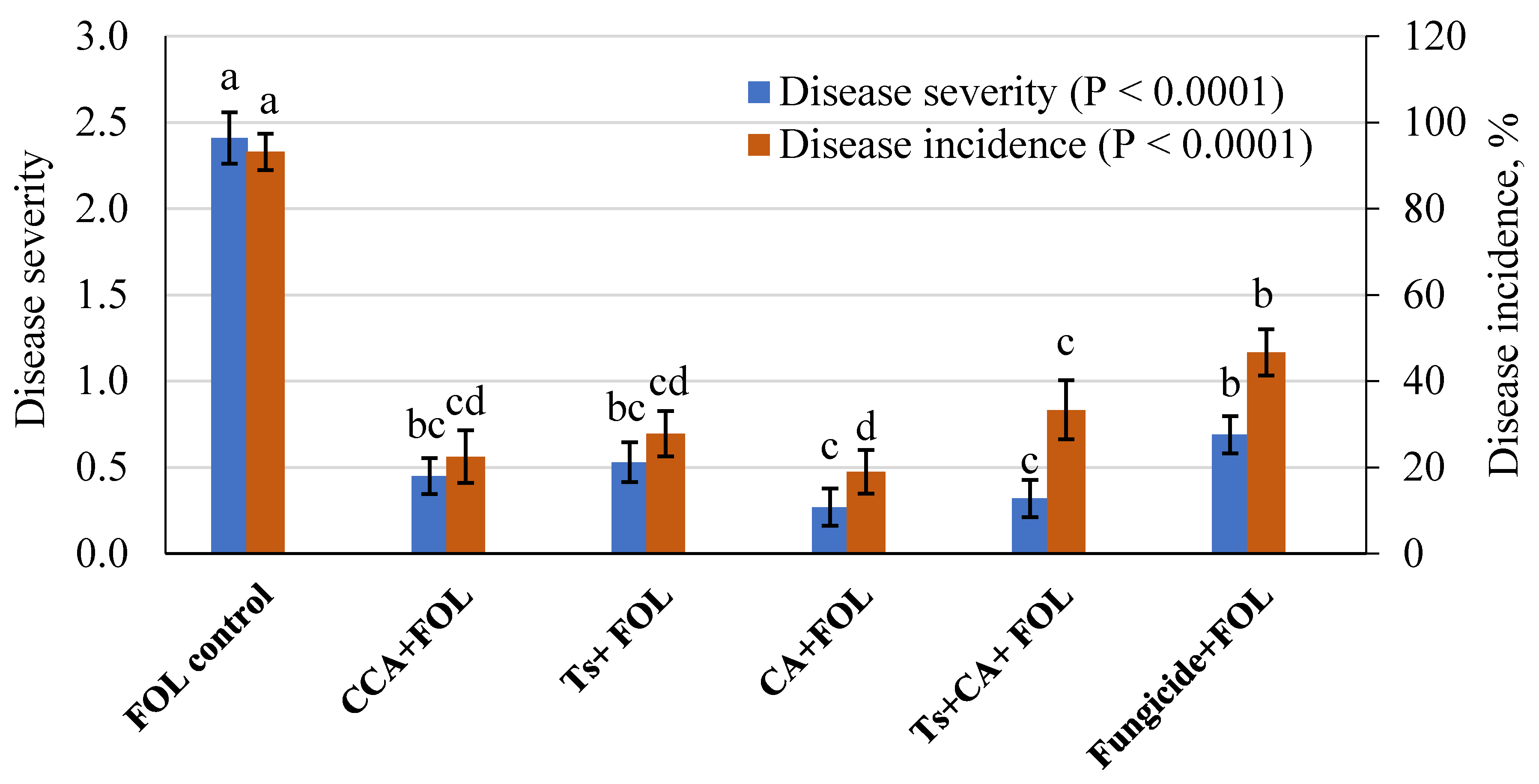

3.7. Wilt Disease Management

3.8. Growth and Yield of Tomato

3.9. Physiological Performance of Tomato Plants

3.9.1. Pigments Content

3.9.2. Total Phenol and Defense-Related Enzymes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lenucci, M.S.; Cadinu, D.; Taurino, M.; Piro, G.; Dalessandro, G. Antioxidant composition in cherry and high-pigment tomato cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2606–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT© FAO. Statistics Division. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Khan, A.R.; El_Komy, M.H.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Hamad, Y.K.; Molan, Y.Y.; Saleh, A.A. Organic management of tomato Fusarium wilt using a native Bacillus subtilis strain and compost combination in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2020, 23, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrios, G.N. Plant Pathology, 5th ed.; Academic Press: St. Louis, MO, USA; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Biju, V.C.; Fokkens, L.; Houterman, P.M.; Rep, M.; Cornelissen, B.J. Multiple evolutionary trajectories have led to the emergence of races in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, H. Impact of fungicide resistance in plant pathogens on crop disease control and agricultural environment. Fungicide Resistance in Plant Pathogens on Crop Disease Control. JARQ 2006, 40, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, A.; Perelló, A.E. Management of Fungal Plant Pathogens; CAB International: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Komy, M.H.; Saleh, A.A.; Eranthodi, A.; Molan, Y.Y. Characterization of novel Trichoderma asperellum isolates to select effective biocontrol agents against tomato Fusarium Wilt. Plant Pathol. J. 2015, 31, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saber, W.I.A.; Ghoneem, K.M.; Rashad, Y.M.; Al-Askar, A.A. Trichoderma harzianum WKY1: An indole acetic acid producer for growth improvement and anthracnose disease control in sorghum. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 654–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Hwang, S.G.; Huang, Y.M.; Huang, C.H. Effects of Trichoderma asperellum on nutrient uptake and Fusarium wilt of tomato. Crop. Prot. 2018, 110, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gurvinder, S.; Ankur, T. Evaluation of different fungicides against Alternaria leaf blight of tomato (Alternaria solani). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Woo, S.L.; Nigro, M.; Marra, R.; Lombardi, N.; Pascale, A.; Ruocco, M.; Lanzuise, S.; et al. Trichoderma secondary metabolites active on plants and fungal pathogens. Open Mycol. J. 2014, 8, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.K. Trichoderma in agriculture: An overview of global scenario on research and its application. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 1922–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekara, C.; Bhatt, J.C.; Kumar, R.; Chandrashekara, K.N. Suppressive soils in plant disease management. In Ecofriendly Innovative Approaches in Plant Disease Management; Singh, V.K., Singh, Y., Singh, A., Eds.; International Book Distributors: Dehhradum, India, 2012; pp. 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías, S.; García-Martínez, A.; Caballero Jimenez, P.; González Grau, J.M.; Tejada Moral, M.; Parrado, J. Rhizospheric Organic Acids as Biostimulants: Monitoring Feedbacks on Soil Microorganisms and Biochemical Properties. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momma, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Simandi, P.; Shishido, M. Role of organic acids in the mechanisms of biological soil disinfestation (BSD). J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2006, 72, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, S.; Harnett, D.; Vaughan, A.; van Sinderen, D. Lactic acid bacteria with potential to eliminate fungal spoilage in foods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Park, Y.; Go, S. Growth inhibition of a phytopathogenic fungus, Colletotrichum species by acetic acid. Microbiol. Res. 2003, 158, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, F.D.; Rauf, M.; Moiemen, N.S.; Bamford, A.; Wearn, C.M.; Fraise, A.P.; Lund, P.A.; Oppenheim, B.A.; Webber, M.A. The antibacterial activity of acetic acid against biofilm-producing pathogens of relevance to burns patients. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; El-Kadi, S.; Sand, M. Effect of some organic acids on some fungal growth and their toxin production. IJAB 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domsch, K.H.; Gams, W.; Anderson, T.H. Compendium of Soil Fungi; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bissett, J. A revision of the genus Trichoderma. Intrageneric classification. Can. J. Bot. 1991, 69, 2357–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, C.P.; Harman, G.E. Trichoderma and Gliocladium. Volume 1: Basic Biology, Taxonomy and Genetics; Taylor and Francis Ltd.: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Meddeb-Mouelhi, F.; Moisan, J.K.; Beauregard, M. A comparison of plate assay methods for detecting extracellular cellulase and xylanase activity. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2014, 66, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, H.A.C.; Dymock, J.F.; Thom, N.S. The rapid colorimetric determination of organic acids and their salts in sewage-sludge liquor. Analyst 1962, 87, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.M.; Andrade, P.B.; Mendes, G.C.; Seabra, R.M.; Ferreira, M.A. Study of the organic acids composition of quince (Cydonia oblonga Miller) fruit and jam. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2313–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTA, International Seed Testing Association. International Rules for Seed Testing; International Seed Testing Association. ISTA: Bassersdorf, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Baki, A.; Anderson, J.D. Vigour determination of Soyabean seed by multiple criteria. Crop. Sci. 1973, 13, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kloepper, J.W.; Tuzun, S. Induction of systemic resistance in cucumber against Fusarium wilt by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhou, L.; Yang, C.; Cao, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Tomato Fusarium wilt and its chemical control strategies in a hydroponic system. Crop. Prot. 2004, 23, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleim, M.A.; Abo-Elyousr, K.A.; Mohamed, A.A.A.; Al-Marzoky, H.A. Peroxidase and polyphenoloxidase activities as biochemical markers for biocontrol efficacy in the control of tomato bacterial wilt. Plant Physiol. Pathol. 2014, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blainski, A.; Lopes, G.C.; De Mello, J.C.P. Application and analysis of the Folin Ciocalteu method for the determination of the total phenolic content from Limonium Brasiliense L. Molecules 2013, 18, 6852–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.M.; Britiz, S.J. Tolerence of field grown soybean cultivers to evaluated ozon level is concurrent with higher leaflet ascorbic acid level, higher ascorbate- dehydroascorbate redox status and long term photosynthetic productivity. Photosynth. Res. 2000, 64, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Metwally, M.M.; Ghoneem, K.M.; Saber, W.I.A. Mycobiota variation in stored rice straw and its cellulolytic profile. PJBS 2014, 17, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ismaiel, A.A.; Papenbrock, J. Mycotoxins: Producing fungi and mechanisms of phytotoxicity. Agriculture 2015, 5, 492–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, W.I.A.; El-Naggar, N.E.; AbdAl-Aziz, S.A. Bioconversion of lignocellulosic wastes into organic acids by cellulolytic rock phosphate-solubilizing fungal isolates grown under solid-state fermentation conditions. Res. J. Microbiol. 2010, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, S.G.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Soccol, V.T.; Soccol, C.R. Pretreatment strategies for delignification of sugarcane bagasse: A review. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2013, 56, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badhan, A.K.; Chadha, B.S.; Kaur, J.; Saini, H.S.; Bhat, M.K. Production of multiple xylanolytic and cellulolytic enzymes by thermophilic fungus Myceliophthora sp. IMI 387099. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanoelo, F.F.; Polizeli, M.L.; Terenzi, H.F.; Jorge, J.A. Purification and biochemical properties of a thermostable xylose-tolerant β-D-xylosidase from Scytalidium thermophilum. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 31, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saber, W.I.A.; El-Naggar, N.E.; El-Hersh, M.S.; El-khateeb, A.Y. An innovative synergism between Aspergillus oryzae and Azotobacter chroococcum for bioconversion of cellulosic biomass into organic acids under restricted nutritional conditions using multi-response surface optimization. Biotechnology 2015, 14, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Kapoor, K.K.; Kundu, B.S.; Mehta, R.K. Identification of organic acids produced during rice straw decomposition and their role in rock phosphate solubilization. Plant Soil Environ. 2008, 54, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coban, H.B. Organic acids as antimicrobial food agents: Applications and microbial productions. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 43, 569–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricke, S. Perspectives on the use of organic acids and short fatty acids as antimicrobials. Poult. Sci. 2003, 82, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, J.K.; Lasure, L.L. Organic acid production by filamentous fungi. In Advances in Fungal Biotechnology for Industry, Agriculture and Medicine; Tkacz, J.S., Lange, L., Eds.; Kluwer Academic, Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 307–340. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, P.W.; Tigano, M.S. Identification and taxonomy of some entomopathogenic Paecilomyces spp. (Ascomycota) isolates using rDNA-ITS sequences. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2006, 29, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badotti, F.; de Oliveira, F.S.; Garcia, C.F.; Vaz, A.B.M.; Fonseca, P.L.C.; Nahum, L.A.; Oliveira, G.; Góes-Neto, A. Effectiveness of ITS and sub-regions as DNA barcode markers for the identification of Basidiomycota (Fungi). BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, H.A.; Miller, A.N.; Pearce, C.J.; Oberlies, N.H. Fungal identification using molecular tools: A primer for the natural products research community. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W. Fungal Barcoding Consortium. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Shukla, N.; Kabadwal, B.C.; Tewari, A.K.; Kumar, J. Review on Plant-Trichoderma-Pathogen Interaction. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 2382–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Marra, R.; Woo, S.L.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma-plant-pathogen interactions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallhi, Z.I.; Rizwan, M.; Mansha, A.; Ali, Q.; Asim, S.; Ali, S.; Hussain, A.; Alrokayan, S.H.; Khan, H.A.; Alam, P.; et al. Citric Acid Enhances Plant Growth, Photosynthesis, and Phytoextraction of Lead by Alleviating the Oxidative Stress in Castor Beans. Plants 2019, 8, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-García, M.; Sol, C.; de Nova, P.J.; Puyalto, M.; Mesas, L.; Puente, H.; Mencía-Ares, Ó.; Miranda, R.; Argüello, H.; Rubio, P. Antimicrobial activity of a selection of organic acids, their salts and essential oils against swine enteropathogenic bacteria. Porc. Health Manag. 2019, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Bulbul, S.H.; Alam, M.F. Effect of Trichoderma on seed germination and seedling parameters in chili. Int. J. Exp. Agric. 2011, 2, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, H.; Jartoodeh, S.V.; Aruee, H.; Mazhabi, M. Would Trichoderma affect seed germination and seedling quality of two muskmelon cultivars, Khatooni and Qasri and increase their transplanting success. J. Biol. Environ. Sci. 2011, 5, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Upadhyay, R.S.; Sarma, B.K.; Singh, H.B. Trichoderma asperellum spore dose depended modulation of plant growth in vegetable crops. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 193, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaptsov, M.; Smirnov, S.; Kutsev, M.; Uvarova, O.; Sinitsyna, T.; Shmakov, A.; Matsyura, A. Antifungal activity of several isolates of Trichoderma against Cladosporium and Botrytis. Ukr. J. Ecol. 2018, 8, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma’nkova, K.; Luhova, L.; Petrivalsky, M.; Pec, P.; Lebeda, A. Biochemical aspects of reactive oxygen species formation in the interaction between Lycopersicon spp. and Oidium neolycopersici. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 68, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, J.C.; Stange, C. Apocarotenoids: A new carotenoid-derived pathway. Subcell. Biochem. 2016, 79, 239–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El_Komy, M.H.; Saleh, A.A.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Hamad, Y.K.; Molan, Y.Y. Trichoderma asperellum strains confer tomato protection and induce its defense-related genes against the Fusarium wilt pathogen. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2016, 41, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, P.; Sharma, S.; Munshi, G.D.; Munshi, S.K. Biochemical changes in sunflower plants due to seed treatment/spray application with biocontrol agents. Phytoparasitica 2008, 36, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.N.; Sarosh, B.R.; Shetty, H.S. Induction and accumulation of polyphenol oxidase activities as implicated in development of resistance against pearl millet downy mildew disease. Funct. Plant Biol. 2006, 33, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janki, N.T.; Patel, S.; Dhandhukia, P.C. Induction of Defense-Related enzymes in banana plants: Effect of live and dead pathogenic strain of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense. ISRN Biotechnol. 2013, 2013, 601303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, F.; Cipollini, J.R. The induction of soluble peroxidase activity in bean leaves by wind induced mechanical perturbation. Am. J. Bot. 1998, 85, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Shoot Length (cm) | Root Length (cm) | Leaves No. Plant−1 | Plant Fresh Weight (g) | Plant Dry Weight (g) | Plant Yield (g) | Plant Fruit Weight (g) | Fruits No. Plant−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 49.8 ± 5.9 ab | 9.20 ± 1.8 a | 7.0 ± 1.0 bc | 8.82 ± 0.8 ab | 1.92 ± 0.1 c | 648.1 ± 28.7 bc | 55.50 ± 3.1 a | 13.00 ± 1.0 abc |

| FOL control | 39.7 ± 7.9 c | 7.30 ± 0.3 b | 6.2 ± 0.8 c | 5.18 ± 0.7 c | 1.10 ± 0.2 d | 283.1 ± 15.6 g | 32.00 ± 0.7 d | 10.00 ± 1.0 f |

| Fungicide + FOL | 47.2 ± 6.1 ab | 9.20 ± 0.8 a | 7.0 ± 1.2 bc | 7.12 ± 1.1 b | 1.94 ± 0.3 c | 410.2 ± 16.7 f | 35.83 ± 1.7 cd | 11.00 ± 0.1 ef |

| CCA + FOL | 52.9 ± 6.4 ab | 9.00 ± 0.7 a | 7.0 ± 0.7 bc | 7.60 ± 0.5 b | 2.02 ± 0.2 bc | 476.1 ± 4.0 e | 44.17 ± 1.4 b | 11.67 ± 0.6 cde |

| Ts + FOL | 51.8 ± 6.1 ab | 9.70 ± 1.8 a | 7.8 ± 1.3 ab | 8.74 ± 2.2 ab | 2.10 ± 0.5 bc | 449.7 ± 22.5 e | 32.92 ± 4.0 d | 12.33 ± 0.6 bcde |

| CA + FOL | 55.1 ± 8.4 a | 9.40 ± 1.1 a | 7.2 ± 1.1 bc | 8.88 ± 2.4 ab | 2.16 ± 0.5 abc | 404.2 ± 7.0 f | 38.39 ± 6.4 c | 11.33 ± 0.6 def |

| Ts + CA + FOL | 51.9 ± 3.4 ab | 9.70 ± 1.0 a | 8.4 ± 0.5 a | 8.36 ± 1.5 ab | 2.24 ± 0.1 abc | 560.0 ± 17.4 d | 45.99 ± 1.9 b | 12.67 ± 0.7 bcd |

| CCA | 54.7 ± 2.5 ab | 10.1 ± 1.7 a | 8.0 ± 0.7 ab | 9.56 ± 0.8 a | 2.42 ± 0.4 ab | 679.3 ± 18.5 a | 55.21 ± 2.8 a | 13.67 ± 0.6 ab |

| Ts | 50.6 ± 3.6 ab | 9.90 ± 1.3 a | 8.4 ± 0.5 a | 9.96 ± 0.8 a | 2.24 ± 0.3 abc | 663.6 ± 20.4 ab | 53.63 ± 3.6 a | 13.33 ± 1.5 ab |

| CA | 46.5 ± 1.9 bc | 9.60 ± 1.1 a | 7.8 ± 0.4 ab | 8.54 ± 0.7 ab | 2.14 ± 0.3 abc | 633.9 ± 5.5 c | 51.90 ± 0.6 a | 13.33 ± 1.5 ab |

| Ts + CA | 53.8 ± 4.8 ab | 10.4 ± 0.5 a | 8.4 ± 0.5 a | 9.60 ± 0.5 a | 2.54 ± 0.2 a | 689.2 ± 40.1 a | 55.13 ± 2.2 a | 14.33 ± 0.6 a |

| p value | =0.0035 | =0.0365 | =0.0008 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment | Chlorophyll Contents (mg/g Fresh Weight) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chla | Chlb | Total Chls | Carotenoid | |

| Control | 2.698 ± 0.07 bc | 1.186 ± 0.07 bc | 3.884 ± 0.07 cd | 0.820 ± 0.01 c |

| FOL control | 1.676 ± 0.19 d | 0.494 ± 0.19 e | 2.170 ± 0.18 h | 0.628 ± 0.07 d |

| Fungicide + FOL | 2.712 ± 0.01 bc | 0.821 ± 0.01 d | 3.532 ± 0.10 f | 0.883 ± 0.01 bc |

| CCA + FOL | 2.570 ± 0.12 c | 0.796 ± 0.12 d | 3.366 ± 0.05 g | 0.856 ± 0.03 c |

| Ts + FOL | 2.662 ± 0.29 bc | 0.941 ± 0.29 cd | 3.603 ± 0.10 ef | 0.845 ± 0.18 c |

| CA + FOL | 2.884 ± 0.30 b | 0.379 ± 0.30 e | 3.263 ± 0.19 g | 1.020 ± 0.14 a |

| Ts + CA + FOL | 2.758 ± 0.03 bc | 0.981 ± 0.03 cd | 3.739 ± 0.03 de | 0.915 ± 0.05 abc |

| CCA | 2.682 ± 0.08 bc | 1.303 ± 0.08 ab | 3.985 ± 0.01 bc | 0.619 ± 0.01 d |

| Ts | 2.597 ± 0.06 bc | 1.508 ± 0.06 a | 4.104 ± 0.02 b | 0.808 ± 0.01 c |

| CA | 2.869 ± 0.0.3 b | 0.949 ± 0.03 cd | 3.818 ± 0.01 d | 0.918 ± 0.01 abc |

| Ts + CA | 3.280 ± 0.01 a | 1.235 ± 0.01 abc | 4.515 ± 0.02 a | 1.009 ± 0.02 ab |

| p value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment | Total Phenol (mg Catechol 100 g−1) | Enzyme (U g−1 Fresh wt.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peroxidase | Polyphenol Oxidase | ||

| Control | 27.48 ± 1.50 ab | 28.77 ± 1.57 d | 18.33 ± 2.08 g |

| FOL control | 16.67 ± 2.08 f | 14.67 ± 1.53 h | 10.00 ± 2.00 h |

| Fungicide + FOL | 19.75 ± 1.39 de | 11.00 ± 1.00 i | 17.33 ± 1.53 g |

| CCA + FOL | 26.87 ± 1.21 ab | 49.43 ± 2.89 a | 20.90 ± 2.82 f |

| Ts + FOL | 23.30 ± 1.47 c | 16.67 ± 1.53 gh | 11.00 ± 2.00 h |

| CA + FOL | 19.50 ± 1.80 de | 34.67 ± 2.52 c | 32.67 ± 2.52 c |

| Ts + CA + FOL | 29.37 ± 2.03 a | 18.33 ± 2.08 fg | 27.00 ± 2.65 e |

| CCA | 22.07 ± 0.90 cd | 11.33 ± 2.08 i | 20.00 ± 2.00 f |

| Ts | 27.90 ± 1.15 ab | 40.00 ± 2.00 b | 45.77 ± 2.36 a |

| CA | 18.23 ± 1.37 ef | 20.23 ± 1.66 ef | 31.10 ± 1.85 d |

| Ts + CA | 26.20 ± 0.72 b | 21.30 ± 2.14 e | 39.43 ± 1.91 b |

| p value | < 0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Askar, A.A.; Saber, W.I.A.; Ghoneem, K.M.; Hafez, E.E.; Ibrahim, A.A. Crude Citric Acid of Trichoderma asperellum: Tomato Growth Promotor and Suppressor of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Plants 2021, 10, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020222

Al-Askar AA, Saber WIA, Ghoneem KM, Hafez EE, Ibrahim AA. Crude Citric Acid of Trichoderma asperellum: Tomato Growth Promotor and Suppressor of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Plants. 2021; 10(2):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020222

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Askar, Abdulaziz A., WesamEldin I. A. Saber, Khalid M. Ghoneem, Elsayed E. Hafez, and Amira A. Ibrahim. 2021. "Crude Citric Acid of Trichoderma asperellum: Tomato Growth Promotor and Suppressor of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici" Plants 10, no. 2: 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020222

APA StyleAl-Askar, A. A., Saber, W. I. A., Ghoneem, K. M., Hafez, E. E., & Ibrahim, A. A. (2021). Crude Citric Acid of Trichoderma asperellum: Tomato Growth Promotor and Suppressor of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Plants, 10(2), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020222