Preliminary Design and Testing of Brush.Q: An Articulated Ground Mobile Robot with Compliant Brush-like Wheels

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Functional design of Brush.Q: A novel articulated wheel-legged robot equipped with compliant brush-like wheels, featuring a compact modular architecture that minimizes chassis exposure to obstacles and enhances adaptability to unstructured terrain.

- Systematic experimental analysis of wheel suspension: Evaluation of different wheel geometries through prototype testing to characterize high-frequency vibrations and assess suspension performance. Obstacle-climbing capabilities are also measured, but the core innovation lies in quantifying and understanding wheel suspension behavior, providing a basis for future wheel selection in wheel-legged robots.

2. Materials and Methods

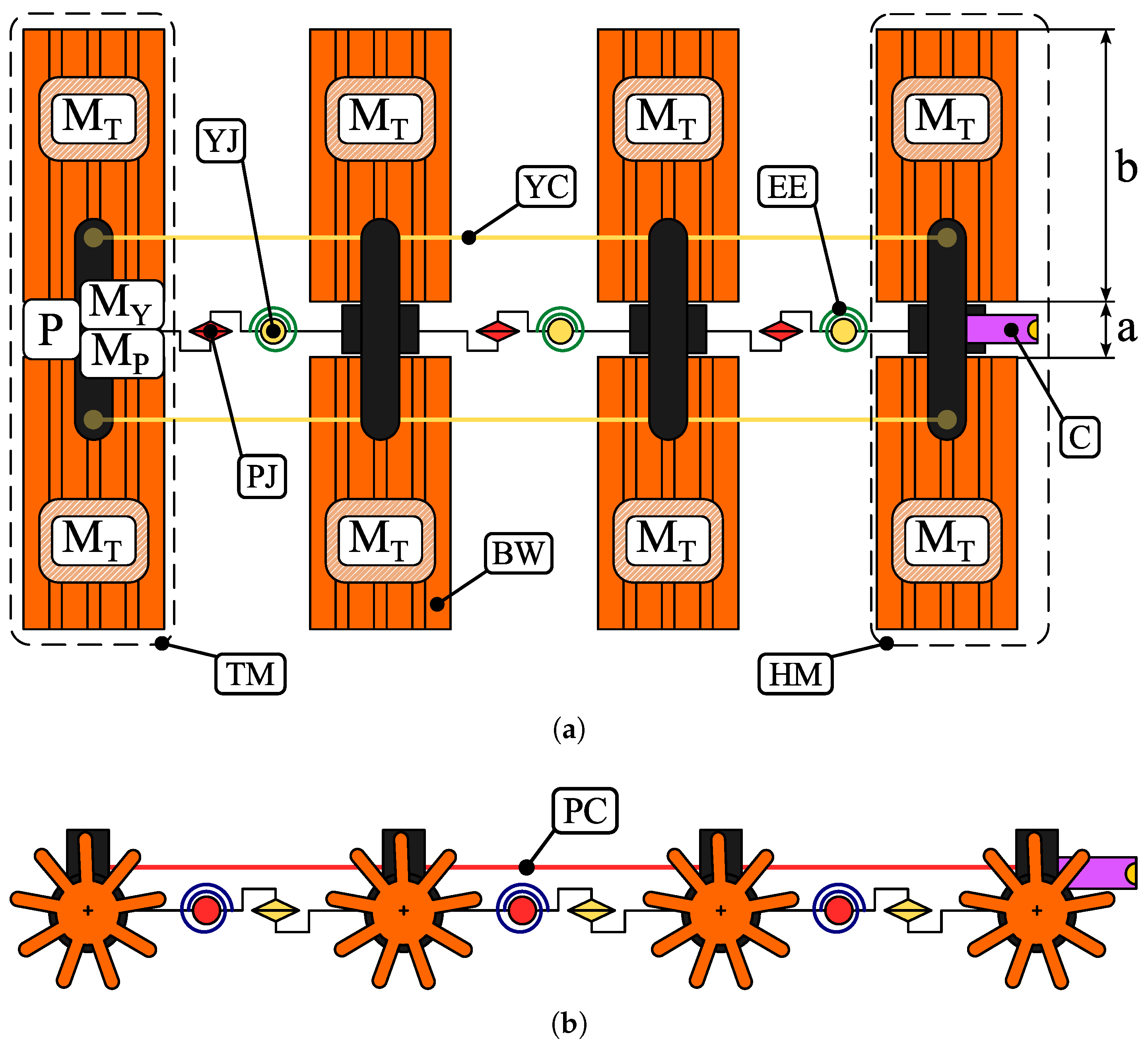

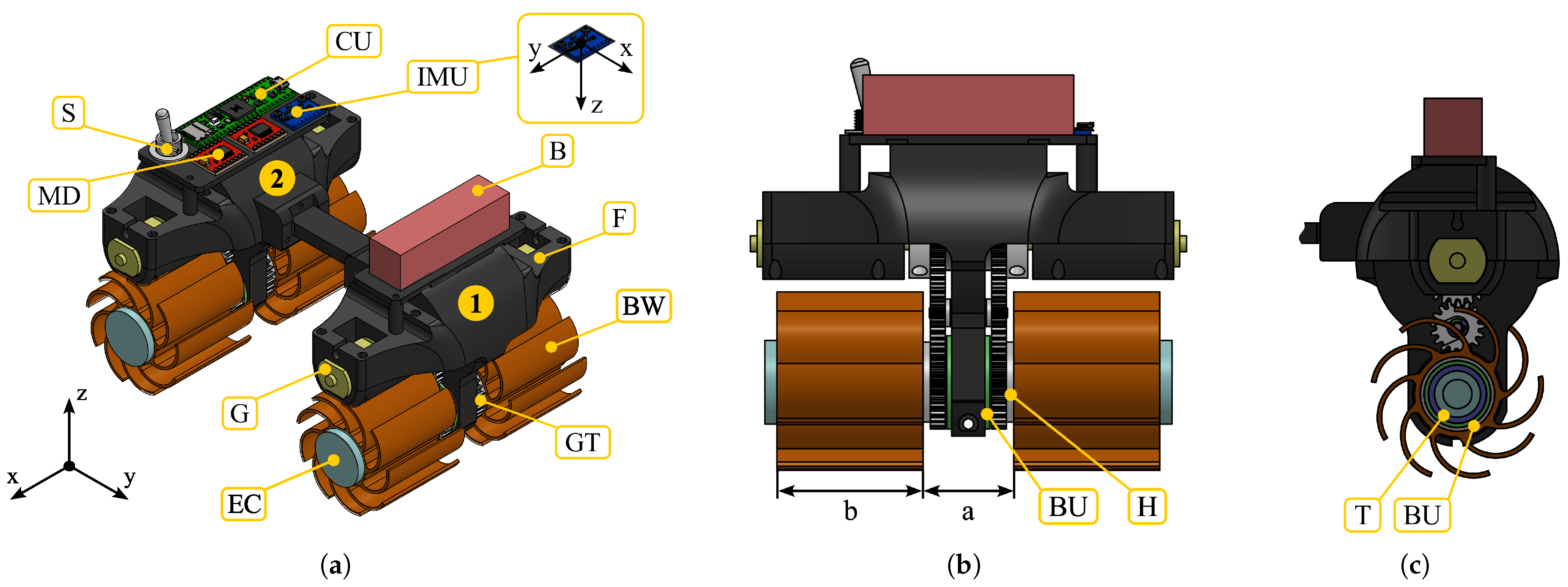

2.1. Functional Design: Mechanical Architecture

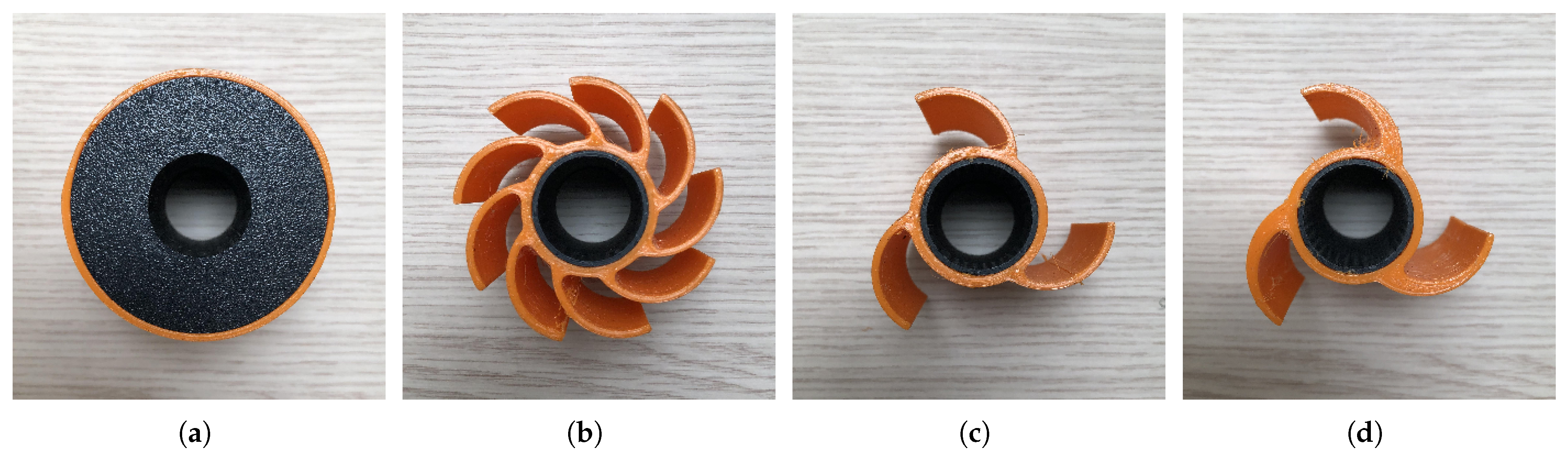

2.2. Brush-like Wheels

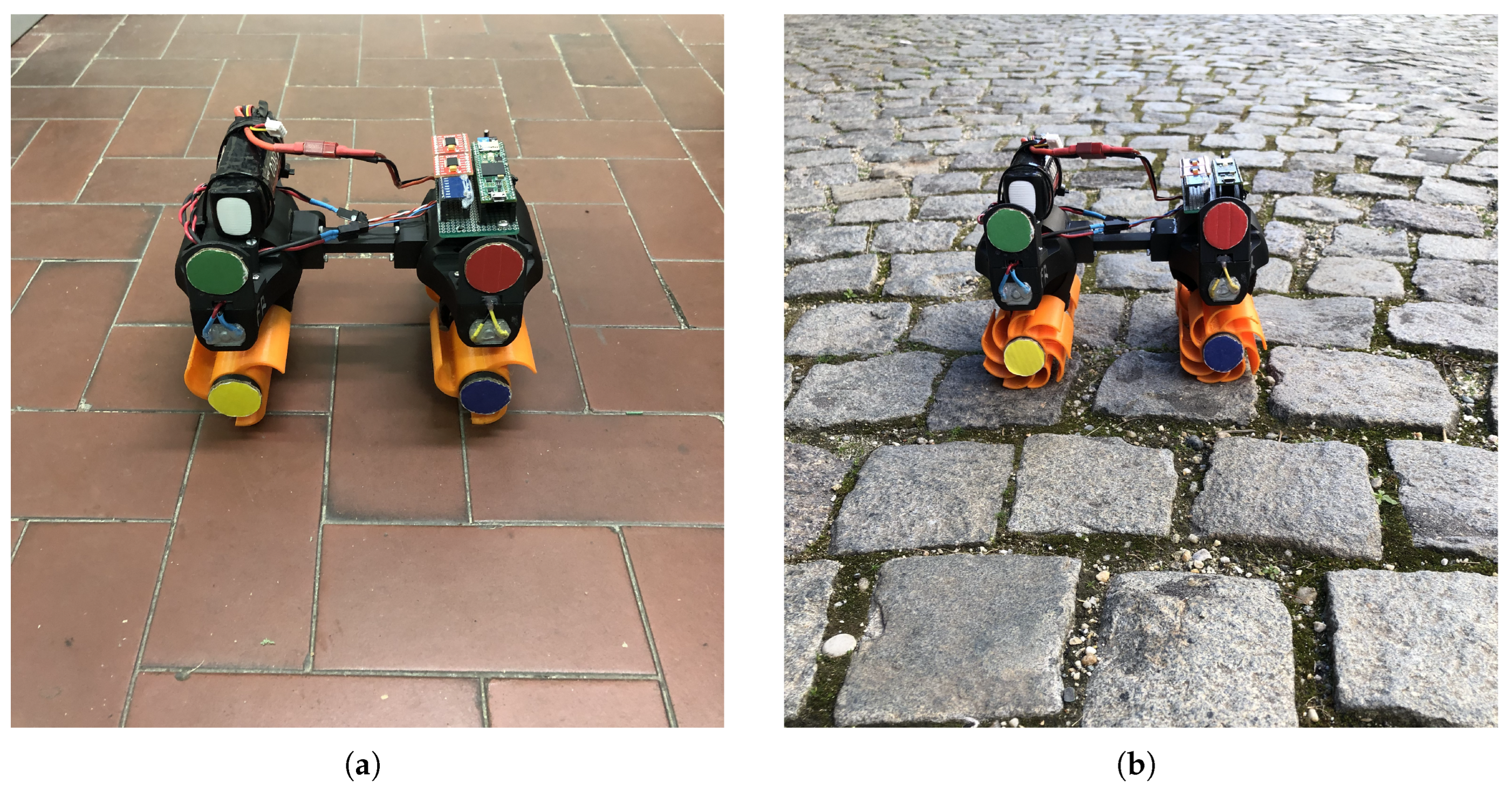

2.3. Prototyping

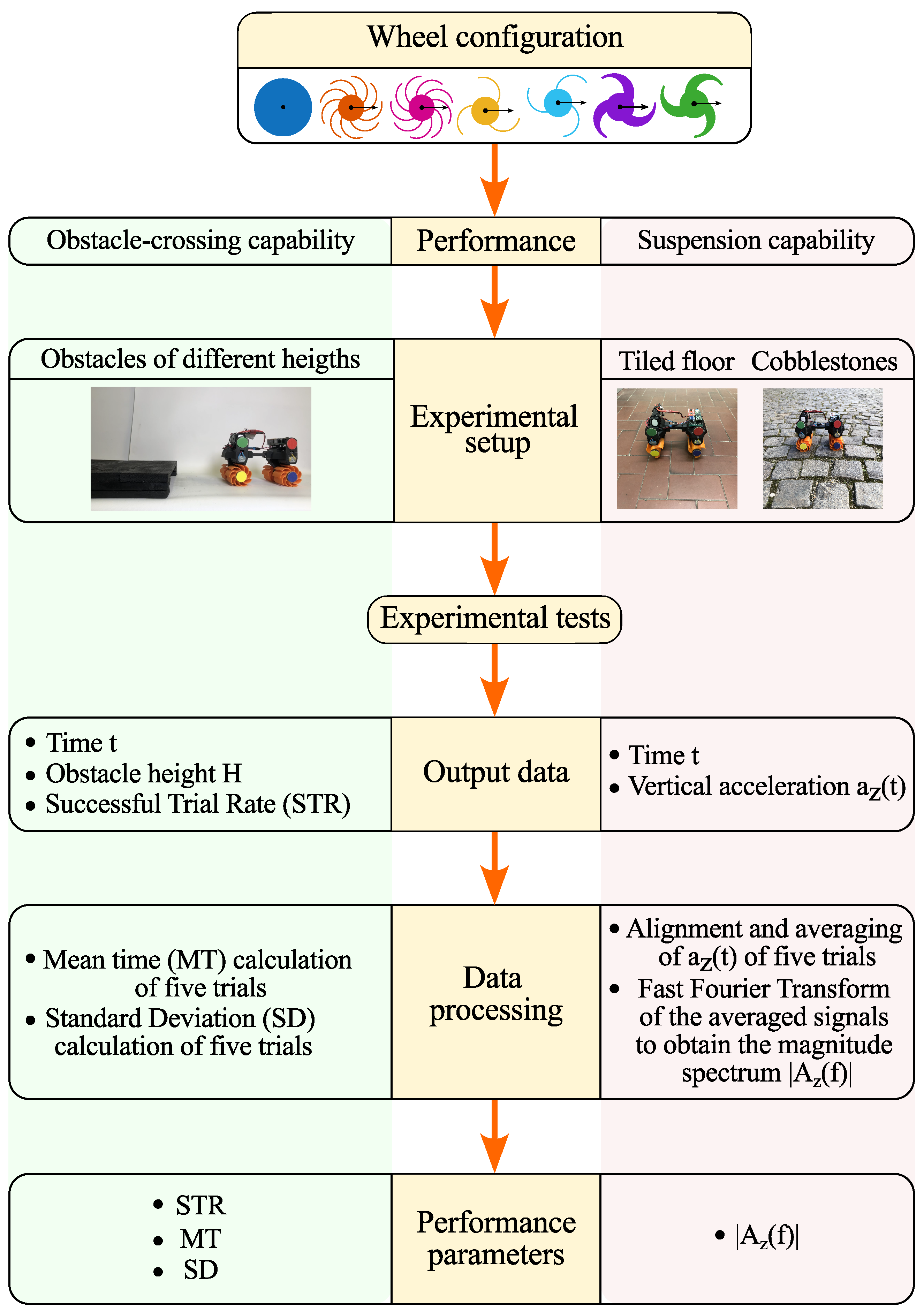

2.4. Experimental Tests

- The number of spokes.

- The wheel rotation direction.

- The cross-sectional profile of the spoke along the radial direction.

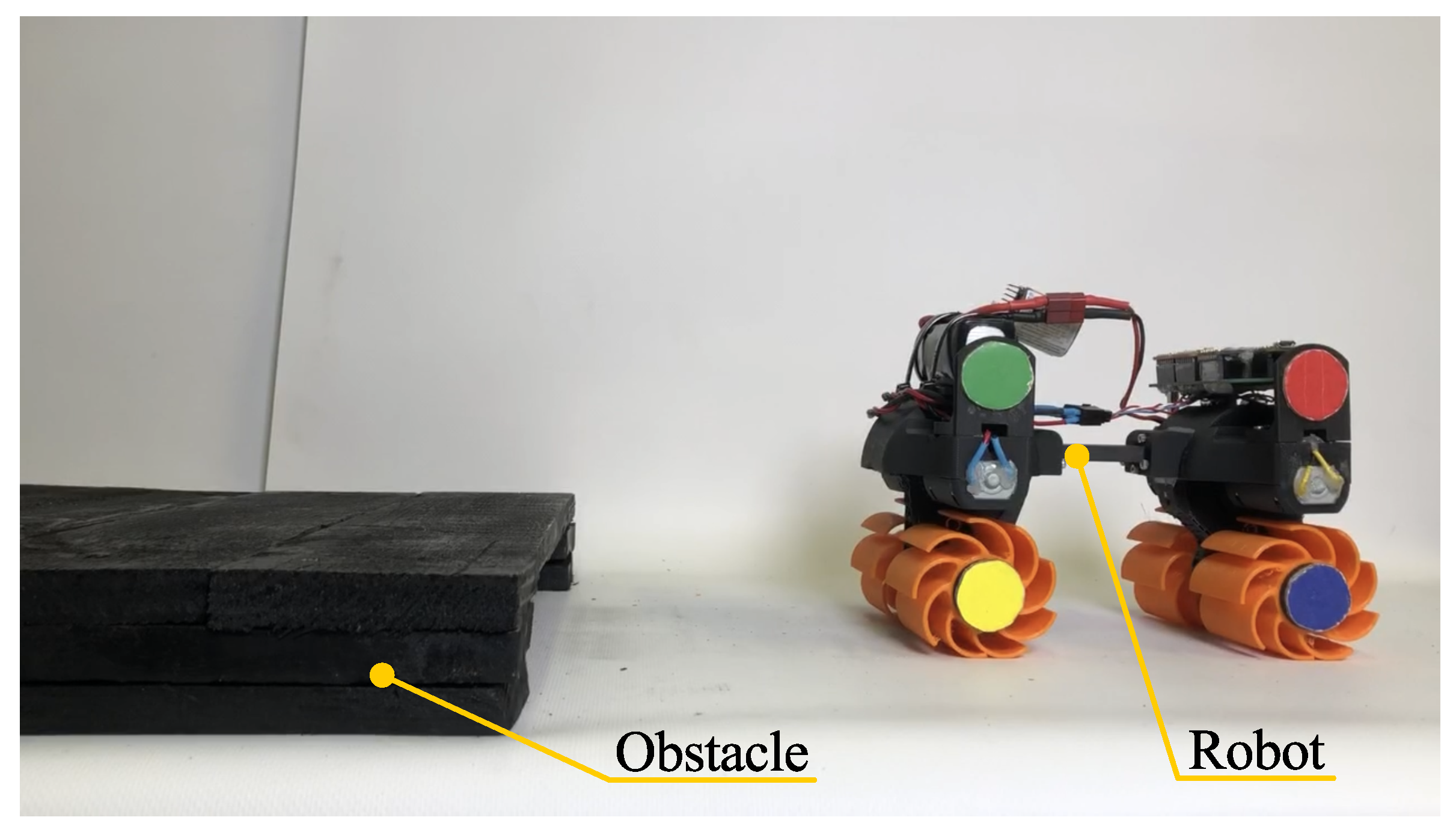

2.4.1. Obstacle-Climbing Capability

2.4.2. Suspension Capability

3. Results and Discussion

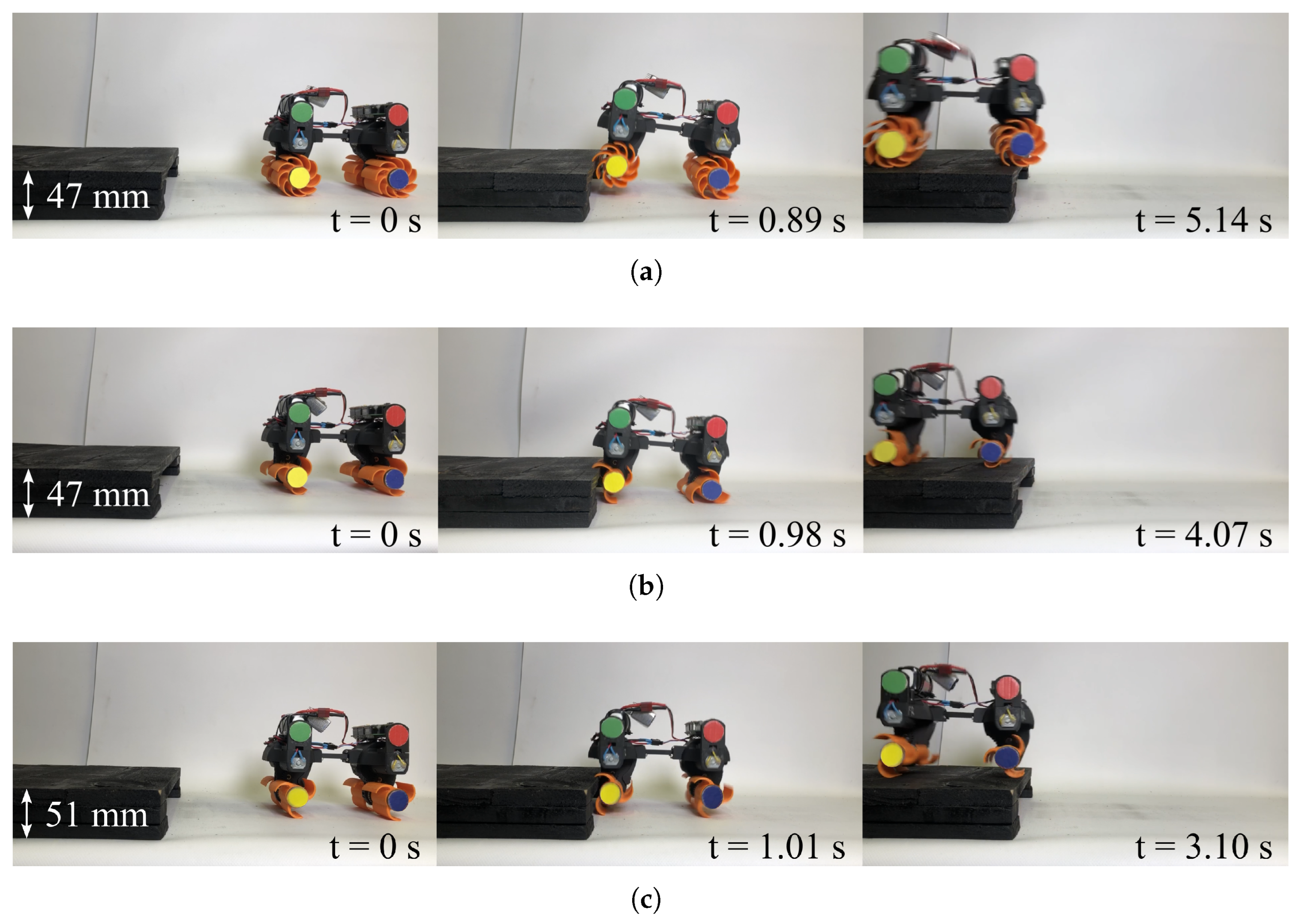

3.1. Obstacle-Climbing Capability Results

- Circular wheel behavior: The circular wheel (7) can overcome only the smallest obstacle, with a height of 0.53R.

- Effect of wheel rotation direction: Regardless of the number of spokes, the backward-facing configurations (2), (4), and (6) outperform the corresponding forward-facing configurations (1), (3), and (5) in terms of both STR and MT. This is attributed to favorable shape-based engagement and reduced interference with the obstacle.

- Influence of the number of spokes: Configurations with three spokes, both forward-facing (3, 5) and backward-facing (4, 6), generally outperform the corresponding nine-spoke configurations. The lower number of spokes enables these wheels to overcome taller obstacles. Moreover, even when the STR is equal, as observed for configurations (2), (4), and (6) at a height of 1.57R, the MT consistently favors the three-spoke configurations (Figure 10a–c).

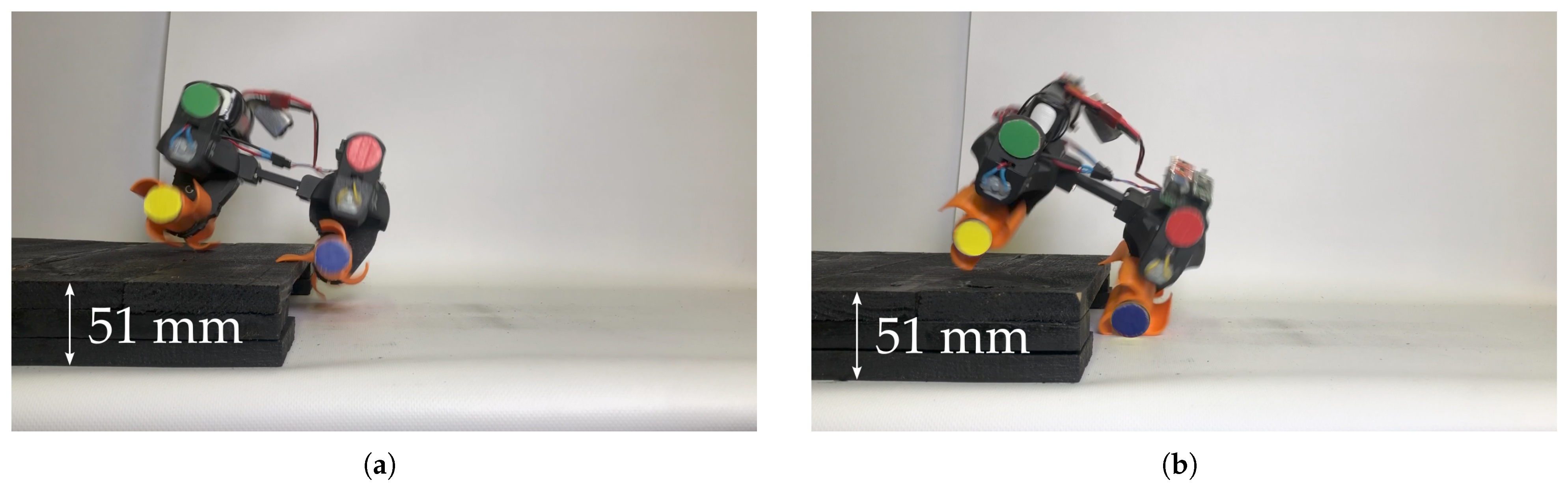

- Effect of spoke stiffness: For a given number of spokes, tapering the spokes to increase stiffness allows the wheel to overcome higher obstacles. With the same robot weight, stiffer spokes raise the wheel height above the ground, allowing the wheel to surmount taller obstacles (Figure 10c). At the same time, the increased stiffness limits the bending of the spoke during contact with the obstacle, thereby facilitating its traversal.

- Stability considerations: Although three-spoke configurations achieve higher obstacle-climbing capability, they are also more unstable: with three spokes, there are fewer simultaneous contact points and a lower contact frequency with the ground, causing the body to oscillate more and increasing the risk of tipping. With nine spokes, the greater number of distributed contacts maintains robot stability even if some spokes are not perfectly synchronized. Therefore, at equal angular velocity, loss of angular synchronization between the wheels increases the likelihood of lateral tipping (Figure 11).

- Statistical considerations: For a given wheel configuration, both MT and SD increase with the obstacle height, consistent with the increasing difficulty for the wheel to overcome taller obstacles. As noted earlier, for the same obstacle height and wheel rotation direction, MT consistently favors the three-spoke configurations. SD values are nearly zero for an obstacle height of 0.53R for all configurations and remain below one except for the forward-facing configurations (3) and (5) at an obstacle height of 1.57R, where SD equals 3.07 s and 1.71 s, respectively. This result further highlights the favorable shape-based engagement and reduced obstacle interference characteristic of the backward-facing configurations.

3.2. Comparison of Obstacle-Climbing Capability with Other Wheel-Legged Designs

3.3. Suspension Capability Results

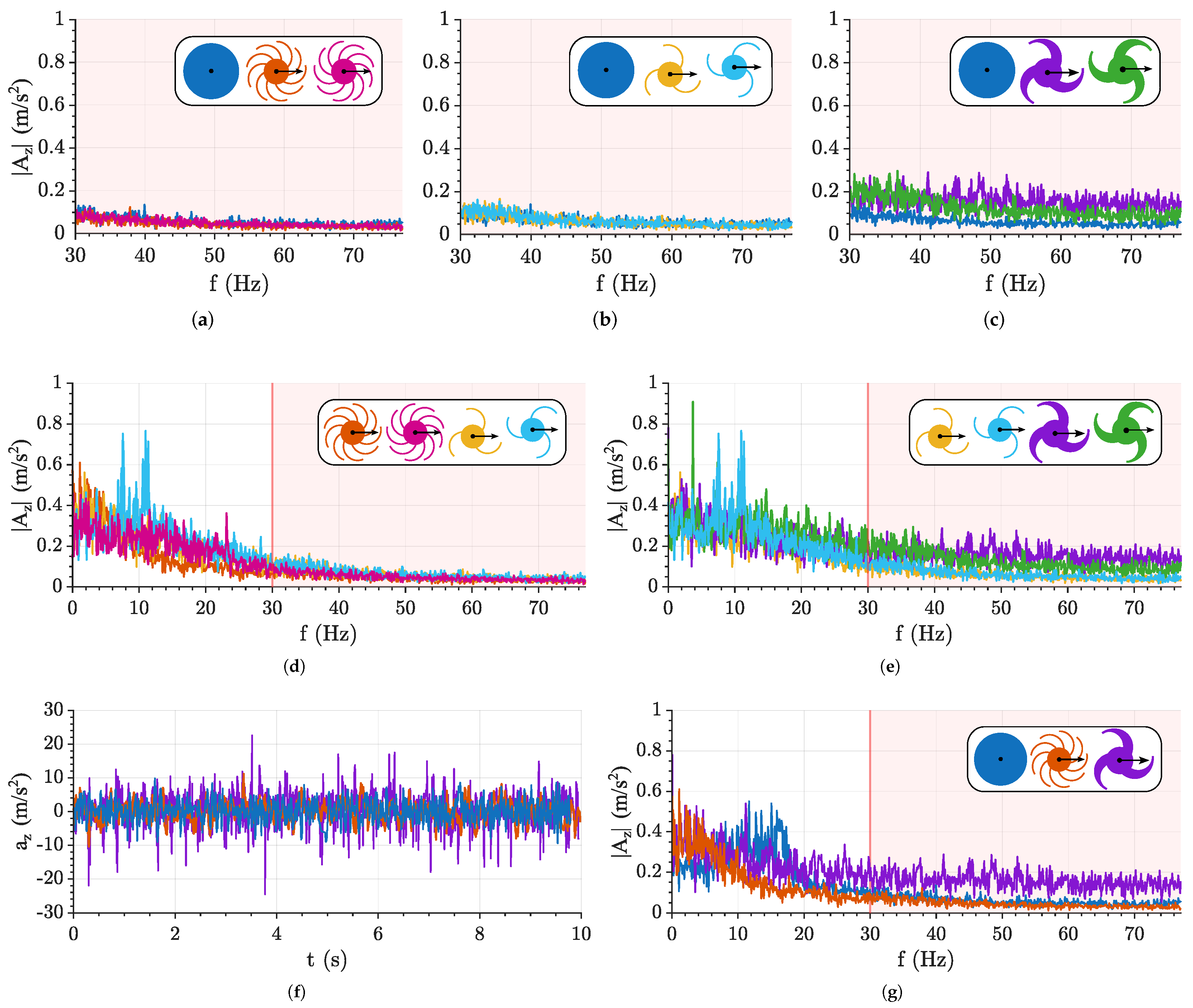

- Tiled floor: The circular wheel, together with the nine-spoke forward-facing wheel, exhibits the best suspension capability, with the latter being slightly superior (Figure 12a,g). The wheel rotation direction does not appear to be a significant parameter (Figure 12a,b), except for the tapered three-spoke wheel (Figure 12c), where the forward-facing configuration appears to yield worse results, e.g., it exhibits higher vibration levels at higher frequencies. The number of spokes highlights an advantage for the nine-spoke wheel (Figure 12d) because the contact with the ground is more continuous. The tapering of the three-spoke wheel further reduces suspension capability due to the increased stiffness (Figure 12e). In summary, the circular wheel and the nine-spoke forward-facing wheel are the best-performing configurations, whereas the tapered three-spoke wheel is the worst-performing one, as indicated by the acceleration peaks in (Figure 12f).

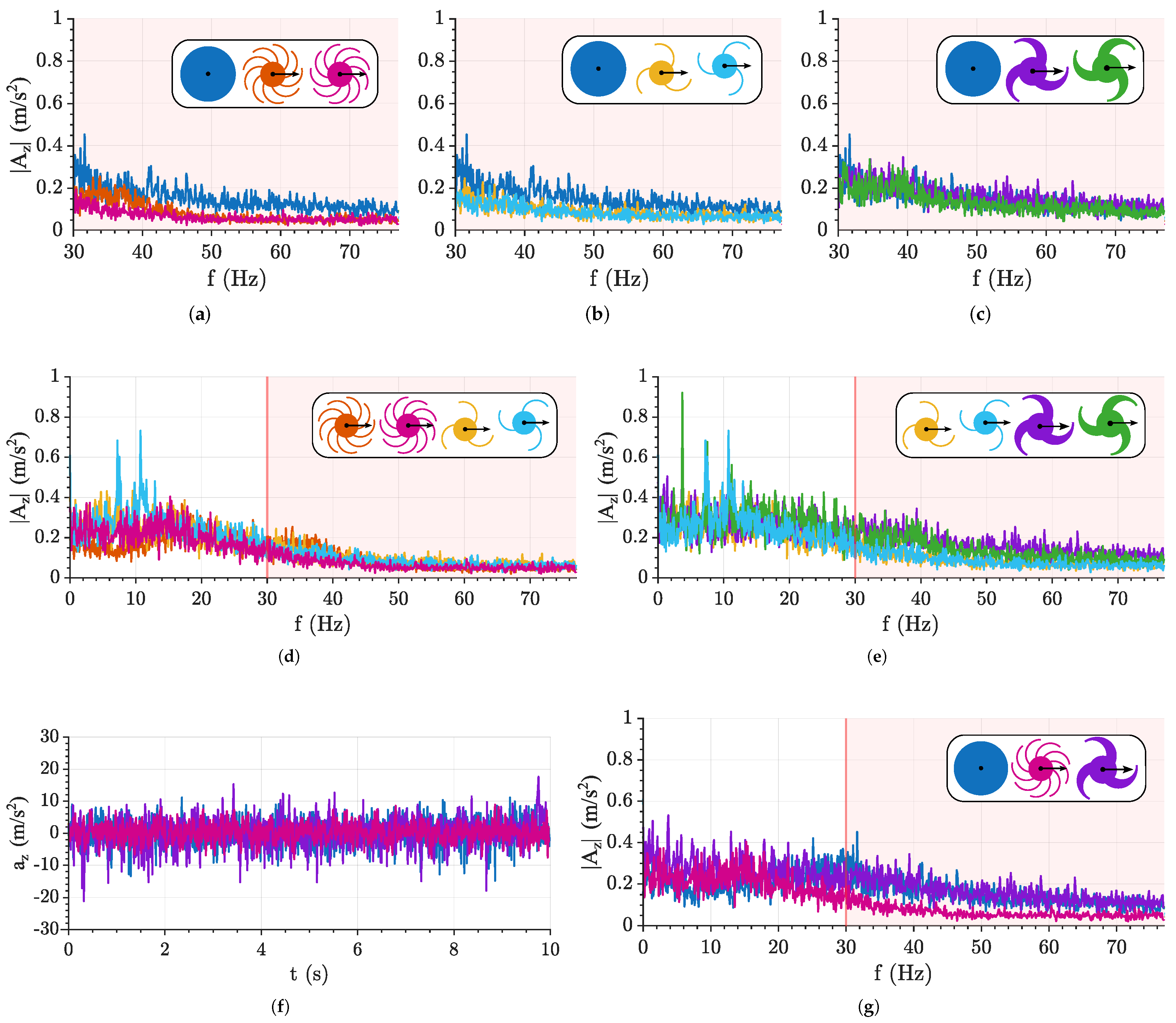

- Cobblestones: On this terrain, the circular wheel performs the worst (Figure 13a,g) because its shape does not adapt well to irregularities. The nine-spoke wheel, on the other hand, maintains consistently good capabilities (Figure 13a,f). Wheel rotation direction has little impact overall, except for a slight degradation in the forward-facing configurations of the three- and nine-spoke wheels (Figure 13a,b), which becomes more noticeable for the tapered three-spoke wheel (Figure 13c). Regarding the number of spokes, three-spoke wheels show reduced capability (Figure 13d), with further degradation for the tapered profile (Figure 13e). In summary, the nine-spoke forward-facing wheel is the best-performing configuration, while the circular wheel and the tapered three-spoke wheel are the worst, as shown by the acceleration peaks in Figure 13f.

3.4. Performance Overview

- The circular wheel consistently exhibits the lowest capabilities, confirming its limited suitability for operation on unstructured or irregular terrains.

- The wheel rotation direction has a measurable impact on both capabilities, with a clear improvement when transitioning from the forward-facing to the backward-facing configuration.

- A reduction in the number of spokes leads to a degradation in suspension capability, while concurrently enhancing obstacle-climbing capability, independently of the rotation direction.

- A variation in the spoke thickness, considered in this context as a tapering of the spoke profile, does not affect the obstacle-climbing capability in the forward-facing configuration, while it leads to a noticeable improvement in the backward-facing configuration. However, profile tapering consistently reduces the suspension capability for both rotation directions.

4. Conclusions and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Processing and Spectral Analysis Method

References

- Bruzzone, L.; Quaglia, G. Review article: Locomotion systems for ground mobile robots in unstructured environments. Mech. Sci. 2012, 3, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.; Campbell, D.; Grimminger, F.; Buehler, M. Reliable stair climbing in the simple hexapod ‘RHex’. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.02CH37292), Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002; Volume 3, pp. 2222–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Yoon, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.S.; Seo, T. Review on Transformable Wheel: Mechanism Classification and Analysis According to Mechanical Complexity. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2025, 26, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Gu, J.; Yu, C.; Rosendo, A. OmniWheg: An Omnidirectional Wheel-Leg Transformable Robot. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 5626–5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertyüz, İ.; Tanyıldızı, A.K.; Taşar, B.; Yakut, O. FUHAR: A transformable wheel-legged hybrid mobile robot. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 133, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Lin, H.S.; Lin, Y.M.; Lin, P.C. TurboQuad: A Novel Leg–Wheel Transformable Robot with Smooth and Fast Behavioral Transitions. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1025–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.; Offi, J.; Kingsley, D.; Ritzmann, R. Improved mobility through abstracted biological principles. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and System, Lausanne, Switzerland, 30 September–4 October 2002; Volume 3, pp. 2652–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Fnadi, M.; Benamar, F. Rolling based locomotion on rough terrain for a wheeled quadruped using centroidal dynamics. Mech. Mach. Theory 2020, 153, 103984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wang, S.; Shi, L.; Li, J.; Yue, B. Horizon-stability control for wheel-legged robot driving over unknow, rough terrain. Mech. Mach. Theory 2025, 205, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.; Quinn, R.; Bachmann, R.; Ritzmann, R. Abstracted biological principles applied with reduced actuation improve mobility of legged vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2003) (Cat. No.03CH37453), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–31 October 2003; Volume 2, pp. 1370–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eich, M.; Grimminger, F.; Kirchner, F. A Versatile Stair-Climbing Robot for Search and Rescue Applications. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Workshop on Safety, Security and Rescue Robotics, Sendai, Japan, 21–24 October 2008; pp. 35–40, ISSN 2374-3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles, I.; Walker, I.D. Continuum Robotic Elements for Enabling Negotiation of Uneven Terrain in Unstructured Environments. WSEAS Trans. Appl. Theor. Mech. 2013, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.V.; Conard, G.G.; Sanchez, A.G.; Sun, Y.; Onal, C.D. Lizard: A Novel Origami Continuum Mobile Robot for Complex and Unstructured Environments. Reports 2025, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Yue, H.; Wang, W.D. Crawling Soft Robot Exploiting Wheel-Legs and Multimodal Locomotion for High Terrestrial Maneuverability. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 4230–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Guan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Sun, T. Design, Analysis, and Experiment of a Wheel-Legged Mobile Robot. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Robot | Wheel Type | Wheel Structure | Body Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| RHex [2] | Non-trasformable | C-shaped single leg | Rigid |

| OmniWheg [4] | Trasformable | 4-lobe | Rigid |

| FUHAR [5] | Trasformable | 6-lobe | Rigid |

| TurboQuad [6] | Trasformable | 2-lobe | Rigid |

| Whegs I [7] | Non-trasformable | Straight-curved 3-spoke | Rigid |

| Whegs II [10] | Non-trasformable | Straight-curved 3-spoke | Articulated |

| ASGUARD [11] | Non-trasformable | Straigth 5-spoke | Articulated |

| FRESE I [12] | Non-trasformable | 5-spoke | Articulated |

| FRESE II [12] | Non-trasformable | 5-spoke | Continuum |

| FRESE III [12] | Non-trasformable | 5-spoke | Articulated |

| FRESE IV [12] | Non-trasformable | 5-spoke | Continuum |

| Lizard [13] | Non-trasformable | Curved 3-spoke | Continuum |

| Crawling soft robot [14] | Non-trasformable | 8-spoke | Continuum |

| Wheel-legged Mobile Robot [15] | Non-trasformable | Straight-curved 3-spoke | Articulated |

| Robot | Body Structure | Max Height (R) |

|---|---|---|

| Tapered 3-spoke wheel prototype | Rigid | 1.7 |

| RHex [2] | Rigid | 1.25 |

| Whegs I [7] | Rigid | 1.5 |

| Whegs II [10] | Articulated | 1.38 |

| FRESE IV [12] | Continuum | 3.6 |

| Lizard [13] | Continuum | 2.4 |

| Crawling soft robot [14] | Continuum | 2.2 |

| Configuration |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstacle-climbing capability | Very low | Medium | Low | High | Low | Very high | Very Low |

| Suspension capability | Very high | Very high | Medium | High | Very low | Low | Very high |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toccaceli, L.; Botta, A.; Colucci, G.; Tagliavini, L.; Visconte, C.; Quaglia, G. Preliminary Design and Testing of Brush.Q: An Articulated Ground Mobile Robot with Compliant Brush-like Wheels. Robotics 2026, 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15010003

Toccaceli L, Botta A, Colucci G, Tagliavini L, Visconte C, Quaglia G. Preliminary Design and Testing of Brush.Q: An Articulated Ground Mobile Robot with Compliant Brush-like Wheels. Robotics. 2026; 15(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleToccaceli, Lorenzo, Andrea Botta, Giovanni Colucci, Luigi Tagliavini, Carmen Visconte, and Giuseppe Quaglia. 2026. "Preliminary Design and Testing of Brush.Q: An Articulated Ground Mobile Robot with Compliant Brush-like Wheels" Robotics 15, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15010003

APA StyleToccaceli, L., Botta, A., Colucci, G., Tagliavini, L., Visconte, C., & Quaglia, G. (2026). Preliminary Design and Testing of Brush.Q: An Articulated Ground Mobile Robot with Compliant Brush-like Wheels. Robotics, 15(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15010003