1. Introduction

Agriculture has always been a cornerstone of human civilisation, sustaining food production, providing essential raw materials, and shaping landscapes and livelihoods. In the current global context—characterised by climate change, population growth, and increasing labour shortages—the agricultural sector faces mounting pressure to enhance resilience, efficiency, and sustainability. Recognising the strategic importance of agriculture in achieving global sustainability, both academic and institutional actors have increasingly focused their attention on advancing research and development in this domain [

1,

2,

3]. Among these, one in particular has played a pivotal role in terms of scope and importance, considering the number of countries involved, but more importantly, the underlying design and governance structure that guided its formulation. In January 2015, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) shaped and sustained the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a global initiative that introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 17 interconnected objectives designed to combat inequality, mitigate environmental degradation, and promote inclusive economic growth [

4,

5] (

Figure 1). The structured and integrated nature of the SDGs makes them particularly relevant not only for policymaking, but also as a reference framework for scientific research and technological innovation. In agriculture, this structure enables the identification of multidimensional priorities that go beyond productivity to encompass environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Using the SDGs as a guiding lens reinforces the societal relevance of technical research and encourages interdisciplinary approaches through responsible, human-centred innovation. As stated by FAO Director-General Qu Dongyu:

Conscious of the indivisibility and integrated nature of the SDGs, FAO’s new Strategic Framework and work attests to our complete commitment to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. We accelerate the SDGs through more efficient, inclusive, resilient and sustainable agrifood systems for better production, better nutrition, a better environment, and a better life, leaving no one behind. As conceivable, agriculture plays a direct and fundamental role in many of these goals.

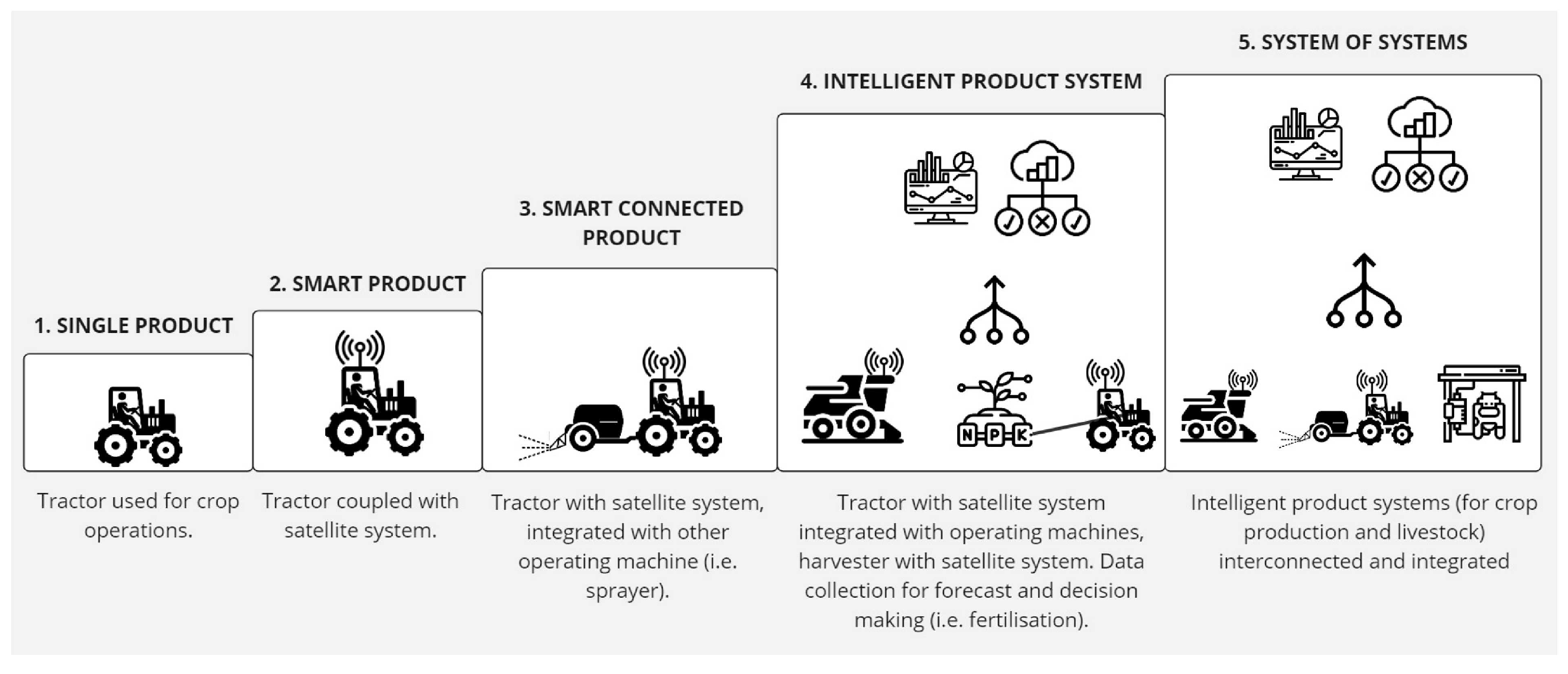

From a scientific perspective, contributing to the SDGs requires rethinking agriculture as a complex and dynamic system rather than a set of isolated operations. Among the various definitions available, a widely adopted one describes a farming system as a set of interrelated agro-economic activities shaped by physical, biological, and human components that interact within a given agrarian context [

7]. This system-oriented perspective highlights how land, crops, livestock, labour, technology, and management practices are interconnected through ecological and economic processes. Over the past decade, this view has been strengthened by advances in digitalisation, which have transformed traditional farms into increasingly connected and data-driven systems. Azzurra et al. [

8] identify a set of technological enablers—ranging from smart farming tools to digital platforms and connectivity infrastructures—that drive this transition and progressively shift farming systems from standalone operations to integrated “systems of systems” (

Figure 2). Additional studies further expand this perspective by analysing the role of technologies such as blockchain [

9] and digital agriculture frameworks [

10], as well as early bibliometric mappings of digital agriculture research [

11].

Together, these contributions show how digital technologies have become essential components of modern farming systems, enabling improved information flows, decision-making, and operational efficiency.

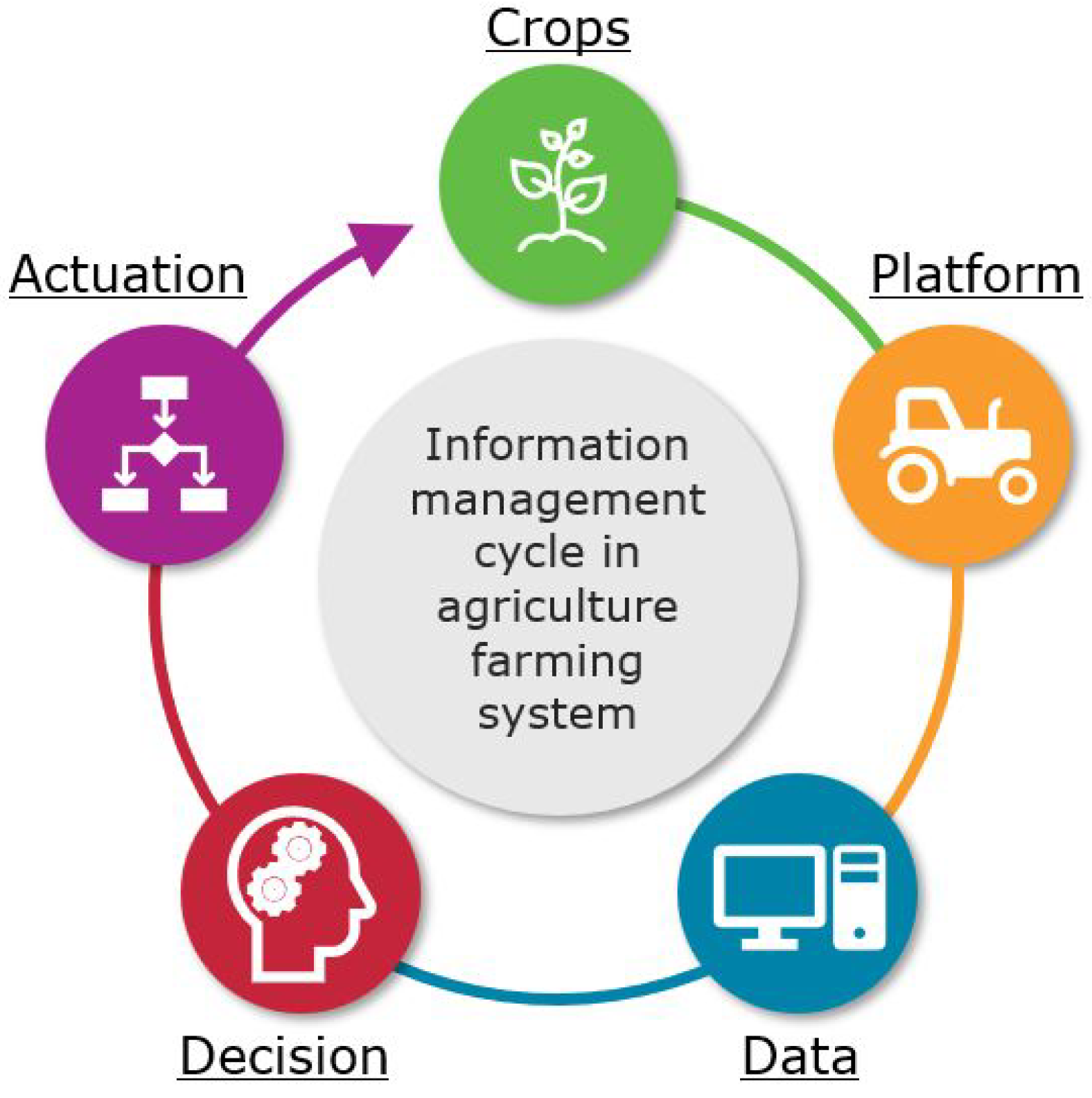

Within the broader digitalisation and data management evolution illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, robotics and automation have progressively emerged as transformative technologies capable of supporting multiple stages of the farming cycle—from precision soil preparation and targeted crop monitoring to selective harvesting and post-harvest processing. Their increasing relevance reflects a shift from traditional mechanisation to systems capable of autonomous perception, decision-making, and execution. Achieving full autonomy in Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RASs) remains a major challenge, particularly in agriculture, where environments are dynamic, unstructured, and highly variable in terms of lighting, weather, crop morphology, and soil conditions. Effective operation under such uncertainty requires capabilities that go beyond classical automation, including dexterous manipulation, proprioceptive and context-aware perception, and online adaptation to disturbances and changing field conditions. In addition, RASs must be designed to interact safely and effectively with humans, a requirement that becomes increasingly critical as robots are expected to operate autonomously over extended time horizons in real-world agricultural settings. In agriculture, the introduction of robotics has often been conflated with mechanisation. Mechanisation refers to machinery—such as tractors or harvesters—used primarily to replace or reduce human labour, typically under direct manual control. Robotic systems, by contrast, embody autonomy: they sense, decide, adapt, and act. As highlighted in the euRobotics 2024 strategy [

12], distinguishing between mechanisation and automation is essential to understanding the societal, functional, and technological implications of modern agricultural systems. Misinterpreting this distinction risks oversimplifying the shift from tool-based assistance to decision-making autonomy, an issue of particular importance when pursuing sustainable, adaptable, and human-centred solutions.

Artificial intelligence (AI) plays a central role in this transition. AI-driven methods—including machine learning, deep learning, decision-support models, and generative approaches—enable RASs to interpret complex sensory inputs, predict environmental dynamics, and adapt their behaviour accordingly. Intelligent automation [

13] integrates these capabilities directly into robotic workflows, supporting applications such as weed detection and control, disease monitoring, yield forecasting, resource optimisation, and real-time operational decision-making across the entire farming system. Recent reviews underscore this technological transformation. Taneja et al. [

14] analyse how AI advancements improve agri-food efficiency, reduce waste, and enhance product quality, positioning robotics as an intelligent tool capable of reducing labour demands and improving operational speed. Shahriar et al. [

15] explore the expanding role of generative AI in agriculture, detailing how advanced models support everything from crop stress diagnosis to autonomous decision planning. A broader and more cross-cutting perspective is offered in Thilakarathne et al. (2025) [

16], who provide an extensive overview of smart agriculture by examining key technologies, application areas, challenges, and emerging trends across hardware and software components.

What clearly emerges from the literature is a high degree of heterogeneity in existing solutions. Both hardware and software are often tailored to specific use cases, resulting in highly customised systems, while such specialisation is often necessary for effective field deployment, it limits broader analyses of research trends, dominant directions, and transferable technological solutions. The widespread adoption of ad hoc designs has produced a large and fragmented body of literature that is difficult to navigate and compare, a challenge further amplified by the growing interdisciplinary interest in the topic. In addition, terminology is not always used consistently: key terms such as artificial intelligence and machine learning are frequently overgeneralised or misapplied, obscuring the actual technological depth of the contributions. Even in well-documented studies, understanding how robotics and AI are concretely applied in daily farming operations remains challenging due to the diversity of agricultural contexts, the lack of standardised evaluation frameworks, and heterogeneous levels of technological adoption.

In response to the increasing complexity of the field, this study provides a structured and critical overview of the evolution of AI techniques in agricultural robotics, while previous reviews primarily describe technological advances, this study adds value by contextualising research output within broader economic drivers and SDG-aligned policy priorities, offering a more holistic understanding of the field’s evolution. It focuses on RASs as intelligent automation platforms, tracing their historical development and identifying key emerging challenges. The analysis is framed from a human-centred perspective, specifically within the paradigm of human-centred artificial intelligence (HCAI) [

17], reflecting a broader socio-technical preoccupation that aligns with several HCAI concerns—namely, the interaction between automation and human roles, operational safety, and decision-making responsibility.

The key contributions of this study are as follows:

A systematic mapping of 25 years of research integrating robotics and AI in agriculture.

A descriptive and thematic analysis of temporal, geographical, and methodological trends using bibliometric tools.

The identification of dominant research areas—such as deep learning for perception, UAV-enabled sensing, data-driven decision systems, and precision agriculture—derived from a systematic bibliometric analysis of two decades of scientific output.

A contextual interpretation of research trajectories in relation to global agricultural challenges and the FAO SDGs.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 presents the methodological approach adopted, detailing the bibliometric tools and analysis pipeline.

Section 3 offers a descriptive analysis of the dataset, highlighting temporal, geographical, and thematic trends.

Section 4 provides the results of the science mapping analysis, revealing the thematic structure and evolution of the research field.

Section 5 discusses the key findings in light of emerging research gaps, global agricultural challenges, and policy frameworks. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by summarising the main contributions and offering concrete research directions for both the robotics and AI communities working in the agricultural domain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question and Filters

Since RASs have advanced significantly through the integration of AI techniques, understanding the trajectory of these innovations necessitates a thorough exploration of their historical development, current trends, and anticipated future directions, as outlined in the previous section. To address these aspects, the central research question guiding this study is as follows:

Q: How do AI algorithms contribute to the self-adaptive behaviour of a robot in an agricultural real-world scenario?

In addition to this primary question, the study aims to explore two specific sub-questions:

Q1: What is the historical evolution of AI contributions in agricultural robotic systems? Are there evident trends or milestones that can be identified?

Q2: Based on the progression of research over the years and the emergence of new topics and keywords, what are the potential academic directions for the near future in the field of agricultural robotics and AI?

A systematic search was conducted using the Scopus database, selected for its extensive coverage of engineering, computer science, and agricultural technology, and its strong indexing of conference papers where AI and robotics research is frequently published. The search targeted the period 2000–2025 using the following query, which combines general AI-related keywords with robotics- and agriculture-specific terms.

| (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR deep OR reinforcement OR “data driven”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“robot*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“agriculture*”)) AND PUBYEAR>1999 AND PUBYEAR<2026 |

The initial search returned 4894 records, which entered the identification phase of the review workflow. The latter was designed in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [

18], with methodological adaptations reflecting the specific requirements of systematic bibliometric research. The project registered on Open Science Framework is available at

https://osf.io/kbnwc from 9 January 2026.

Supplementary Material about PRISMA flow-diagram and checklist is provided as

supplementary material (See

Supplementary Materials). Given the size of the dataset, the first stages of screening were conducted using randomised sampling to ensure that the searching criteria were grounded in evidence and not arbitrarily defined.

A first stratified random sample of the retrieved records was inspected to assess the precision of the query and to identify potential exclusion criteria. This exploratory assessment confirmed that the query successfully captured literature pertinent to AI-enabled agricultural robotics. It also highlighted that non-English publications could not be reliably screened or interpreted within the scope of this study, as bibliometric approaches require consistent textual metadata processing. Given that English is the predominant language of scientific communication in AI, robotics, and agricultural engineering, an English-only filter was applied to ensure methodological consistency. This justified the introduction of the first exclusion criterion (“English only”), subsequently applied to the full dataset.

A second structured sample was analysed in depth, consisting of 50 review papers and 50 non-review papers randomly selected across the publication years and venues represented in the dataset. This stage served two distinct methodological goals:

Evaluating whether review papers should be included in the synthesis. The assessment revealed that reviews are highly heterogeneous in scope, often covering broader domains such as digital agriculture or general AI applications, and lacked the granularity required for thematic evolution analysis. Consequently, review papers were excluded to maintain methodological coherence and avoid duplication of secondary analyses.

Validating the precision and relevance of the query using the 50 non-review papers. This examination confirmed that the query accurately captured studies integrating AI, robotics, and agricultural applications. It also helped refine keyword handling during later preprocessing stages and served as an additional measure to reduce selection bias.

The final dataset consisted of 3673 studies, which were included in the bibliometric analysis and science-mapping procedures. As is typical in bibliometric reviews, the synthesis reflects the scope of indexed publications and available metadata. Additional checks for potential bias were performed during the quantitative analysis to verify the stability of the remaining dataset, including an assessment of document-type distributions (e.g., journal articles vs. conference papers), ensuring that the screening criteria did not distort the underlying publication landscape. Metadata for all included documents was exported directly from Scopus, including title, abstract, keywords, publication year, author affiliations, funding sponsors, and document type. Preprocessing steps involved harmonising keyword variants, removing stop-words, standardising terminology, and unifying metadata formats prior to analysis.

2.2. Science Mapping Tools

Understanding the dynamic evolution of AI in agricultural robotics research necessitates a structured and methodical approach to synthesizing existing knowledge. The sheer volume of publications in this domain introduces potential risks, such as selection biases and information gaps, that may affect the robustness of conclusions. To address this, bibliometric techniques, and in particular science mapping, offer a systematic and objective methodology. These approaches use specialised tools to generate visual representations that uncover dominant research themes, outline the knowledge structure of a field, and expose the relationships between topics [

19,

20,

21]. The mapping process typically involves several key stages: data acquisition, preprocessing, network construction, mapping, metric definition, and final visualisation, while the resulting outputs must then be critically analysed to extract meaningful insights. According to a comprehensive review [

22], at least nine major tools are commonly used in science mapping, each designed for specific tasks within this workflow.

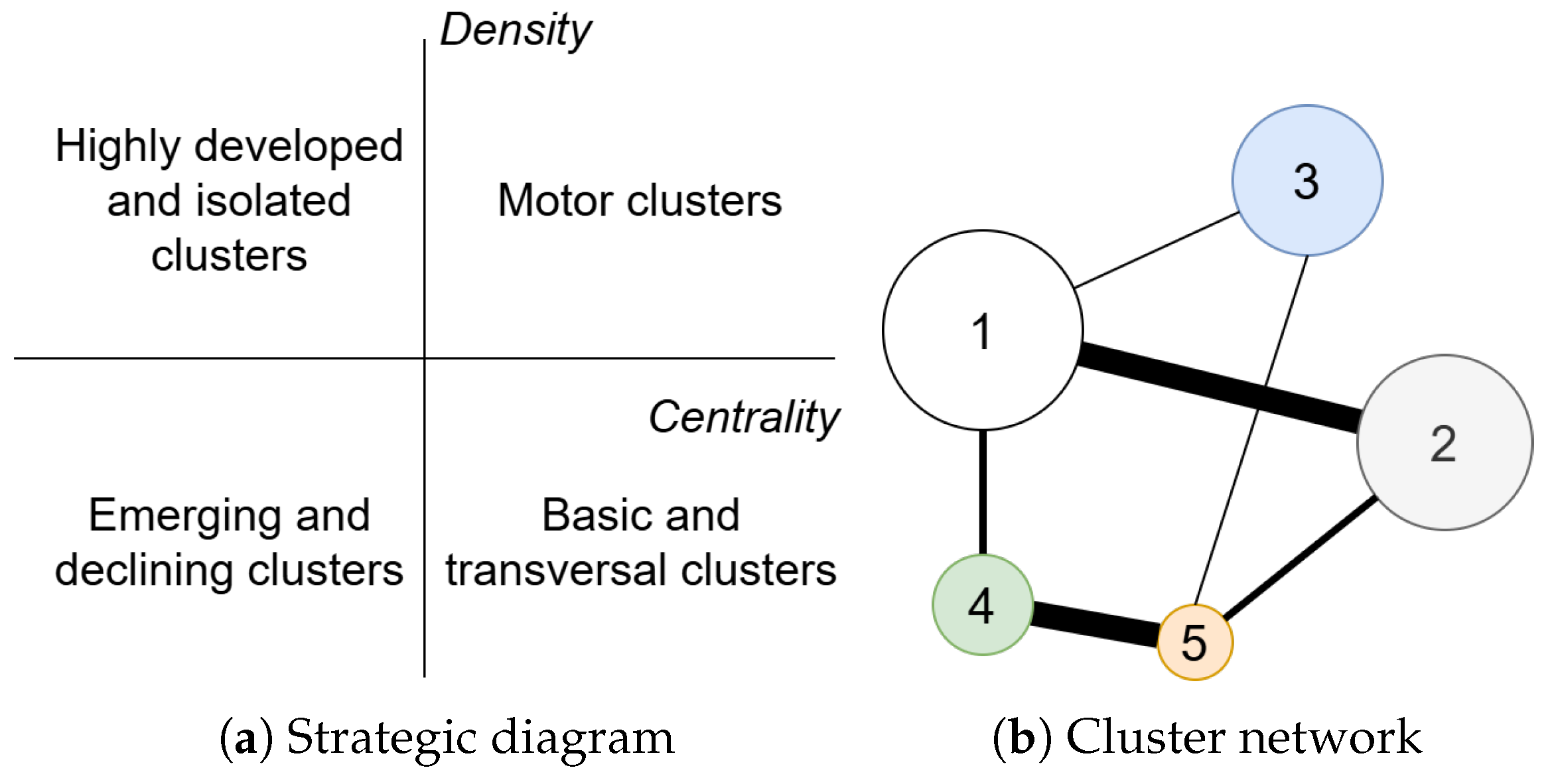

This study employs two of the most widely adopted tools in this domain: VOSviewer and SciMAT. Developed in 2019, VOSviewer [

23] is optimised for visualizing spatial cluster maps (networks) through proximity-based maps, where the spatial arrangement of items reflects the strength of their interrelationships. Thanks to its intuitive interface and minimal parameter requirements, it has become a popular choice for fast and informative visual exploration. SciMAT [

24], released in 2012, offers greater flexibility in configuring knowledge domains and selecting analysis metrics, making it especially suitable for identifying long-term trends and assessing the influence of thematic areas, while VOSviewer focuses on readability and inter-item proximity, SciMAT delivers more layered and analytical visualisations that often require deeper interpretation. Two types of visual outputs generated by SciMAT are used to analyse the thematic structure of the field: the strategic diagram and the cluster network (

Figure 4). These tools serve complementary purposes in science mapping. The strategic diagram provides a two-dimensional representation of research themes, helping to assess their development and relevance within the broader field. Each theme (or cluster) is positioned according to two metrics: density, which reflects the internal cohesion of the cluster, and centrality, which represents the extent of its interaction with other themes. The resulting diagram is divided into four quadrants:

Motor clusters (top-right): well-developed and highly central themes;

Highly developed and isolated clusters (top-left): internally strong but peripheral;

Emerging and declining clusters (bottom-right): weak internal structure but central relevance;

Basic and transversal clusters (bottom-left): limited development and weak integration.

The cluster network, by contrast, offers a more detailed view of the internal structure and relationships within each thematic cluster. It visualises subtopics, co-occurring keywords, or related authors, with edge thickness indicating the strength of connection between nodes. Both the strategic diagram and the cluster network are derived using co-word analysis, a method that examines the frequency with which keywords appear together across a corpus of literature. Frequently co-occurring terms are grouped into clusters, each representing a coherent and recurring research theme. The strength of associations is quantified using the equivalence index, and clusters are then visualised as spheres, whose size can reflect bibliometric indicators such as document count or average citations. This process enables both qualitative and quantitative assessment of the structure and evolution of a research field. Taken together, these two SciMAT outputs provide a detailed and multifaceted view of the thematic evolution, coherence, and connectivity within the field. For a full methodological description, see [

21].

Both instruments are employed to analyse data from 2000 to 2025, spanning the entire 26-year timeframe or analysing sub-periods, providing a comprehensive perspective on long-term trends. The next sections will present both descriptive statistics of the dataset and a detailed discussion of the visual maps, offering a critical interpretation of the field’s development and future directions.

3. Descriptive Analysis

This section offers a descriptive analysis of the temporal, geographical, financial, and semantic characteristics of the retrieved documents, providing quantitative measures that help frame the evolution and distribution of research in agricultural robotics and AI based on preprocessed metadata.

3.1. Keyword Analysis

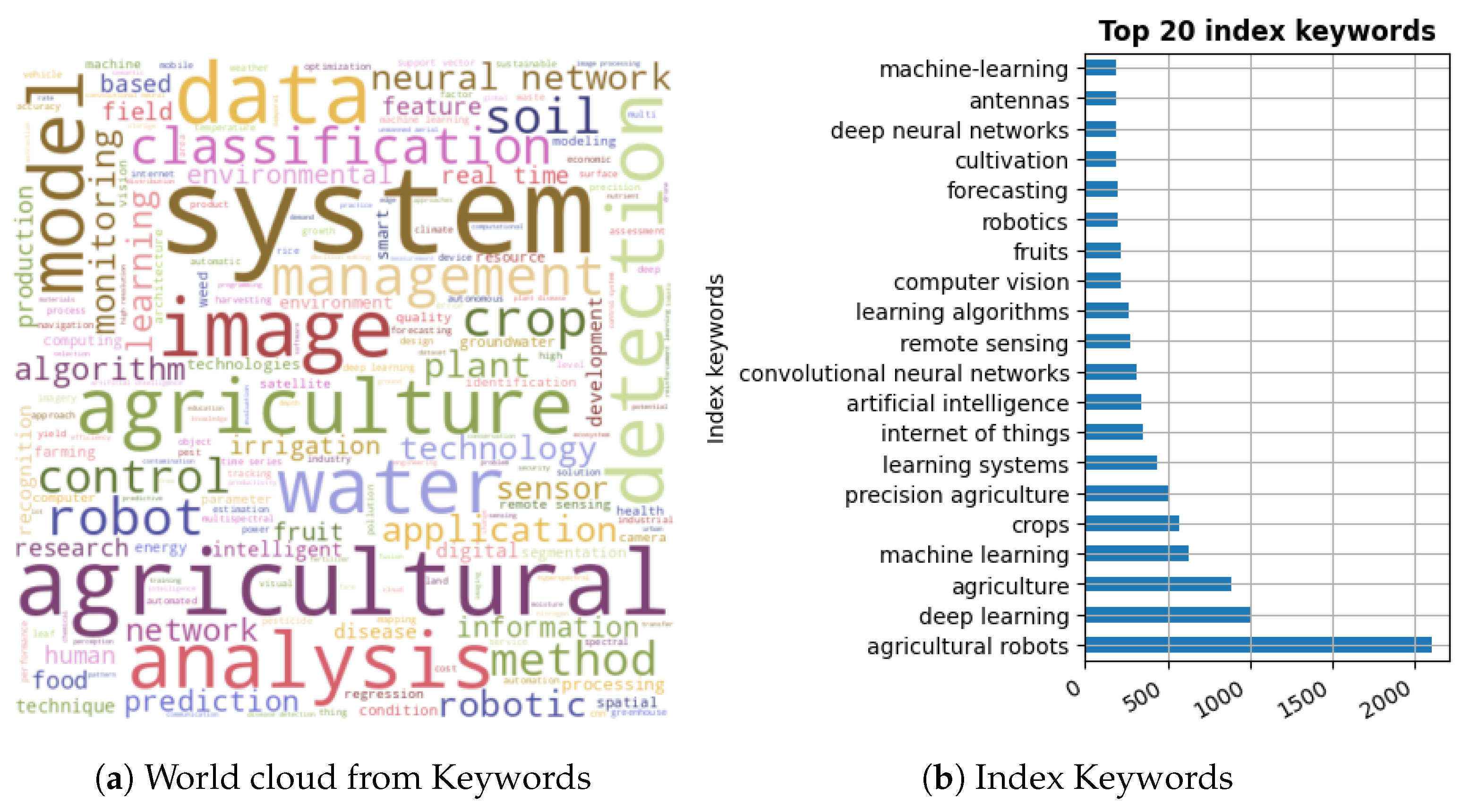

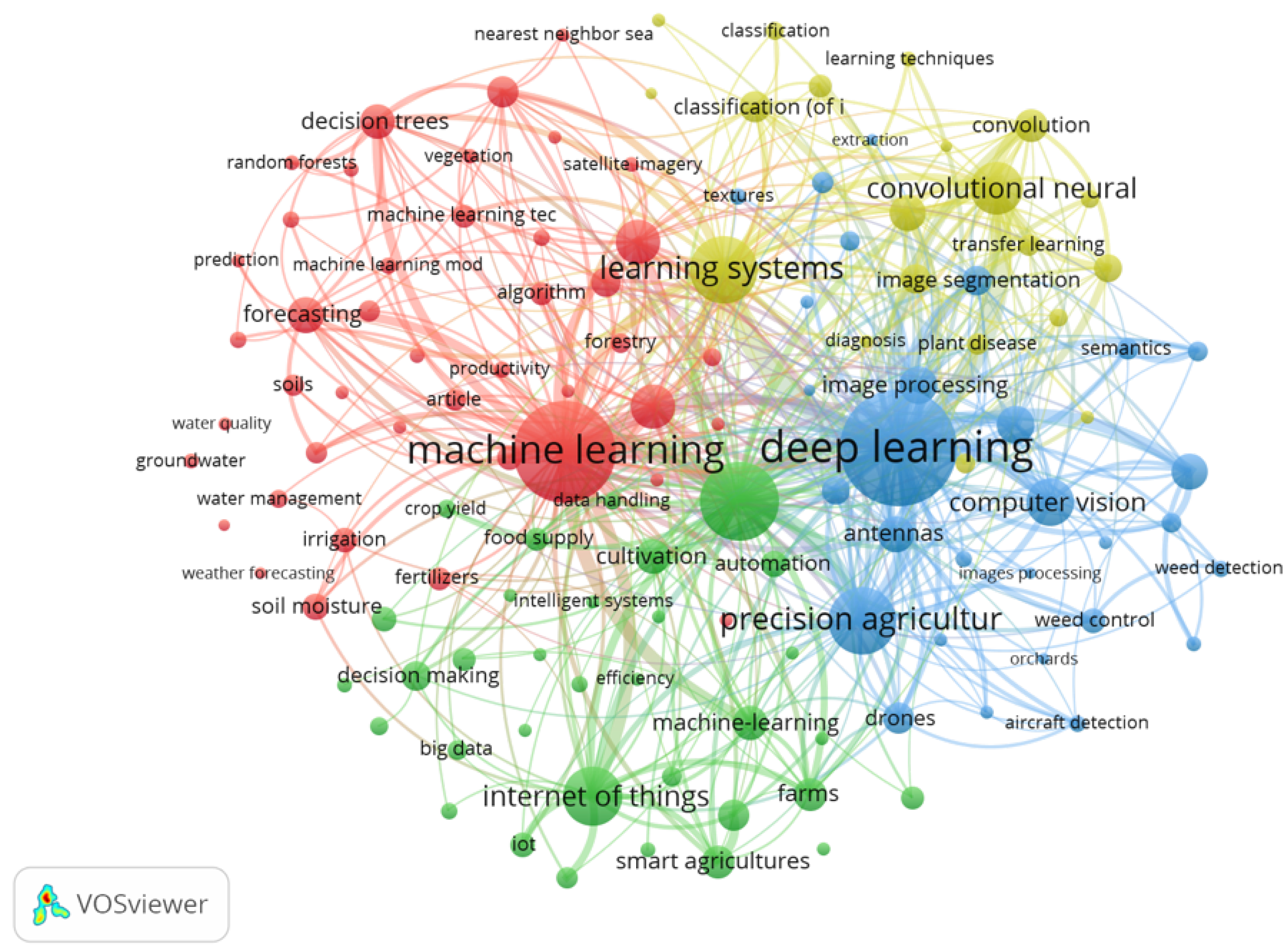

The semantic composition of the dataset was analysed through the frequency of indexed keywords, offering a first overview of the dominant themes and technical focus areas within the field. As shown in

Figure 5, the most frequently recurring terms include

agricultural robots,

deep learning,

agriculture, and

machine learning. These keywords confirm the centrality of both the application domain, agriculture, and the enabling technologies, artificial intelligence and robotics, in the research landscape. Other prominent terms, such as

precision agriculture,

crops,

learning systems, and

Internet of Things highlight the increasing role of data-driven and connected solutions in modern farming practices. Moreover, the presence of keywords like

remote sensing,

computer vision, and

convolutional neural networks suggests that image-based analysis and perception tasks are among the most explored areas.

This distribution reflects a highly interdisciplinary ecosystem, where AI techniques are integrated into field robotics to enhance decision-making, automation, and environmental sensing within the agricultural domain.

3.2. Temporal Trends and Document Types

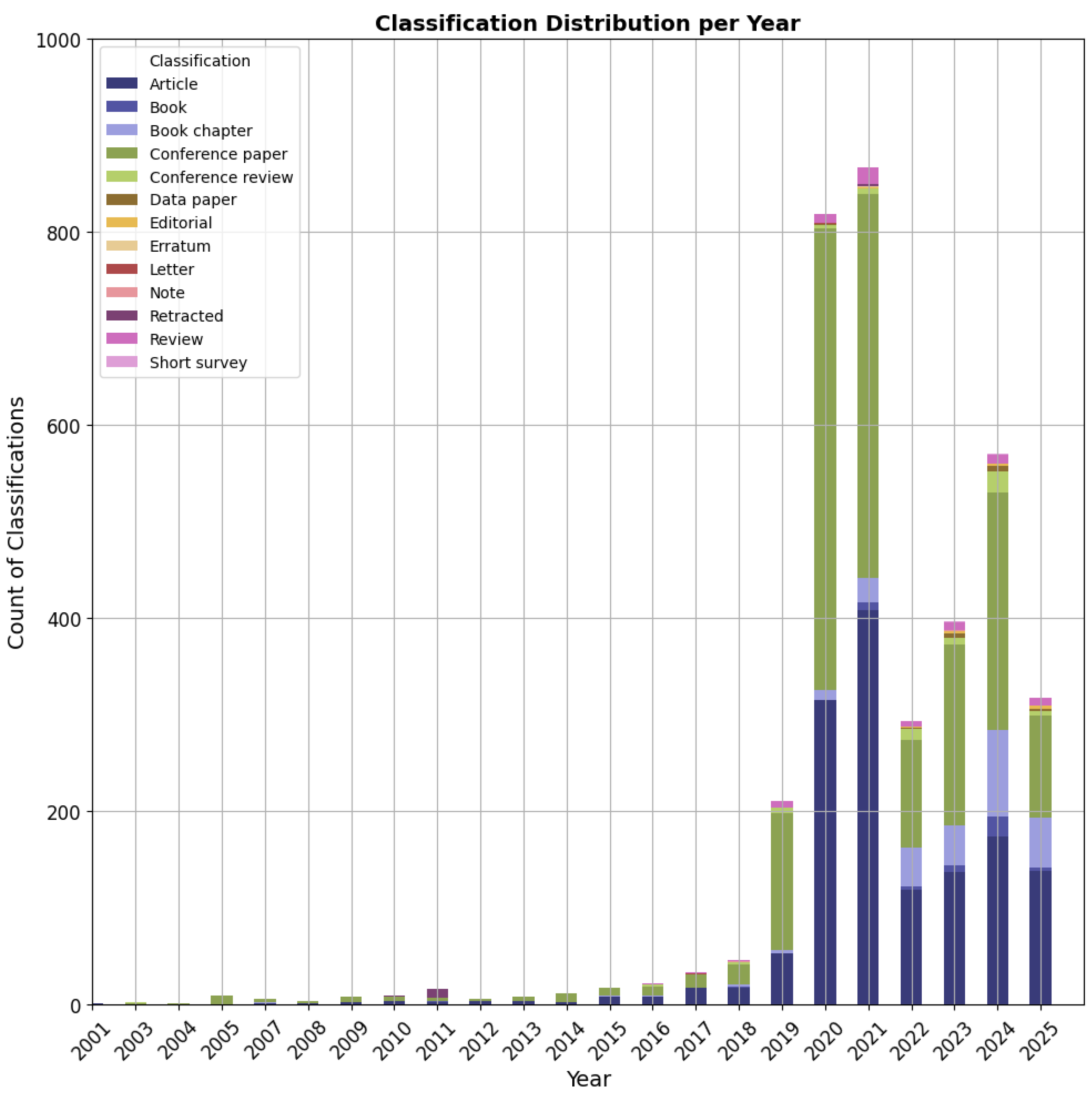

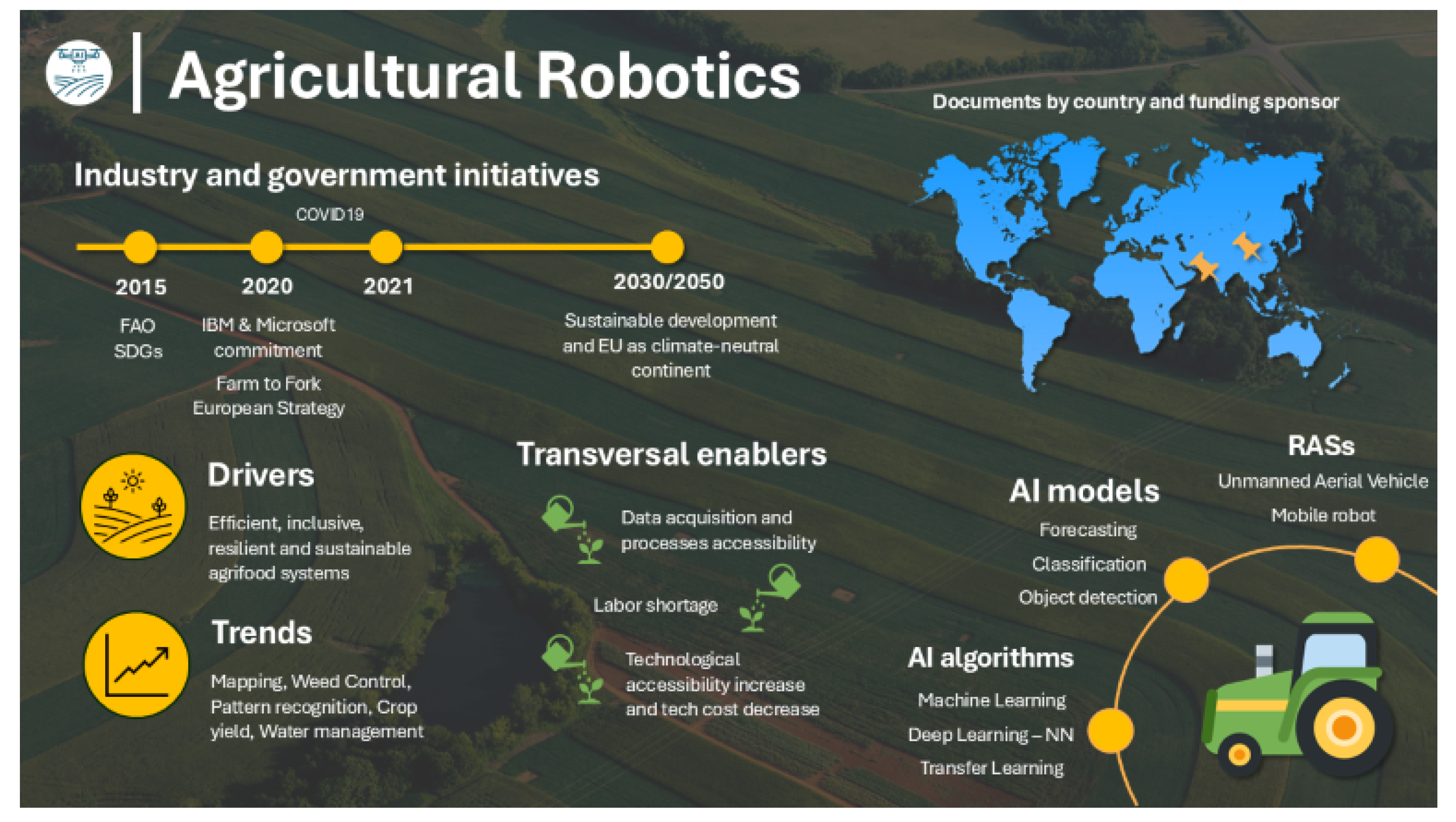

As illustrated in

Figure 6, the number of publications related to agricultural robotics and AI has grown steadily since 2010, with a dramatic surge starting around 2019. The peak is reached between 2020 and 2021, where the annual volume surpasses 850 classified items. In terms of publication types, the distribution is clearly dominated by conference papers and journal articles.

Table 1 reports the 20 most represented conferences and journals, illustrating the diversity of dissemination channels included in the analysis and supporting the robustness of the dataset by demonstrating extensive venue coverage across both engineering and agricultural domains.

Trying to understand the reasons behind this distribution per year, looking at the global panorama and initiatives, some considerations can be done:

After January 2015, when FAO drafted its objectives, there has been a positive push for investment and research. Moreover, in 2020, another document shaped by the United Nations, named

Agriculture 4.0—Agricultural robotics and automated equipment for sustainable crop production, draws additional attention to robotics and agricultural mechanisation for crop production, and its specific applicability in the context of sustainable development [

6]. Looking at the take-home message of this work, it was already clear in the early 2010s that robotics held significant potential in the agricultural field:

“given their versatility, agrobots will be able to perform tasks under conditions that are by nature very labour intensive, and thus make an important contribution to improving sustainable crop production and the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in developing countries. Agricultural robots present an opportunity to increase crop production efficiency, improve agricultural sustainability, and bring innovation and advanced technologies to new areas. FAO has an important role to play in this process, pushing for the inclusive development of this technology and ensuring that new agricultural technologies in the form of automated tools and bots are helping to enhance and promote principles of sustainable intensification of agriculture.”Another initiative, involving the participation of the FAO, saw IBM and Microsoft in 2020 declare their commitment to developing inclusive forms of AI that promote sustainable pathways toward food and nutrition security [

25]. The initiative, titled

AI, food for all, emphasized the role of AI as a crucial enabler for achieving SDGs in the agri-food sector.

Concurrently with the FAO-led initiative, Europe introduced the

Farm to Fork Strategy in 2020 as part of the broader

European Green Deal [

26,

27]. This strategy outlines a vision to transform the way Europeans perceive and value food sustainability, while aiming to position Europe as the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. The goal of the Farm to Fork strategy is to ensure that the food system has a neutral or positive impact on the environment without sacrificing its resiliency, productivity or safety. To achieve these goals, the strategy explicitly calls for innovation and the uptake of digital technologies, including robotics and AI, as key enablers of systemic change. In particular, agricultural automation is recognised as a tool to improve input efficiency, reduce dependency on chemical treatments, and optimise labour use, thereby contributing both to environmental sustainability and to the economic resilience of farms. In this context, robotics is not only a technological opportunity but also a policy-driven necessity, aligned with the broader objectives of the European Green Deal.

The last, yet perhaps most significant, factor explaining the significant peak in 2020/2021 is the COVID-19 pandemic. A wide body of literature has explored its impact on food security, supply chains, consumer demand, and price fluctuations [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The impact on the agricultural system is thus direct and obvious, as well as the boost on possible solutions that permit overcoming the same situation in the future. Considering the distribution of documents by subject area during the COVID-19 period (

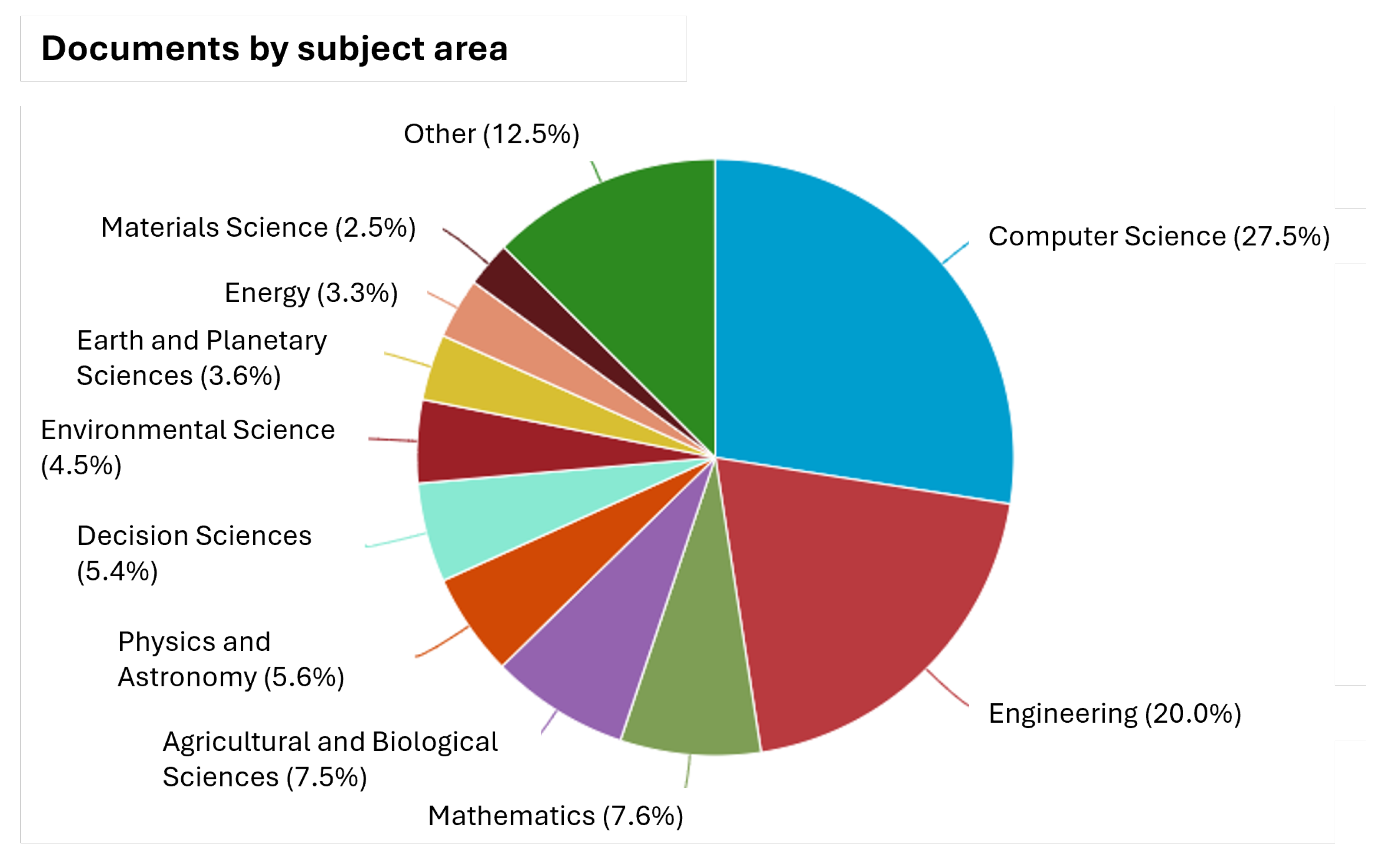

Figure 7), while Computer Science (20.5%) and Engineering (15.9%) remain prominent, the data reveal a more heterogeneous distribution compared to pre-pandemic/post-pandemic trends. Fields such as Medicine, Mathematics, Agricultural, Biological Sciences, and Social Sciences each account for around 8% of contributions, suggesting an increased interdisciplinary engagement. This shift likely reflects the broader societal relevance and urgency of agricultural innovation during the pandemic, attracting research interest from traditionally less-involved disciplines.

3.3. Geographical Distribution of Contributions

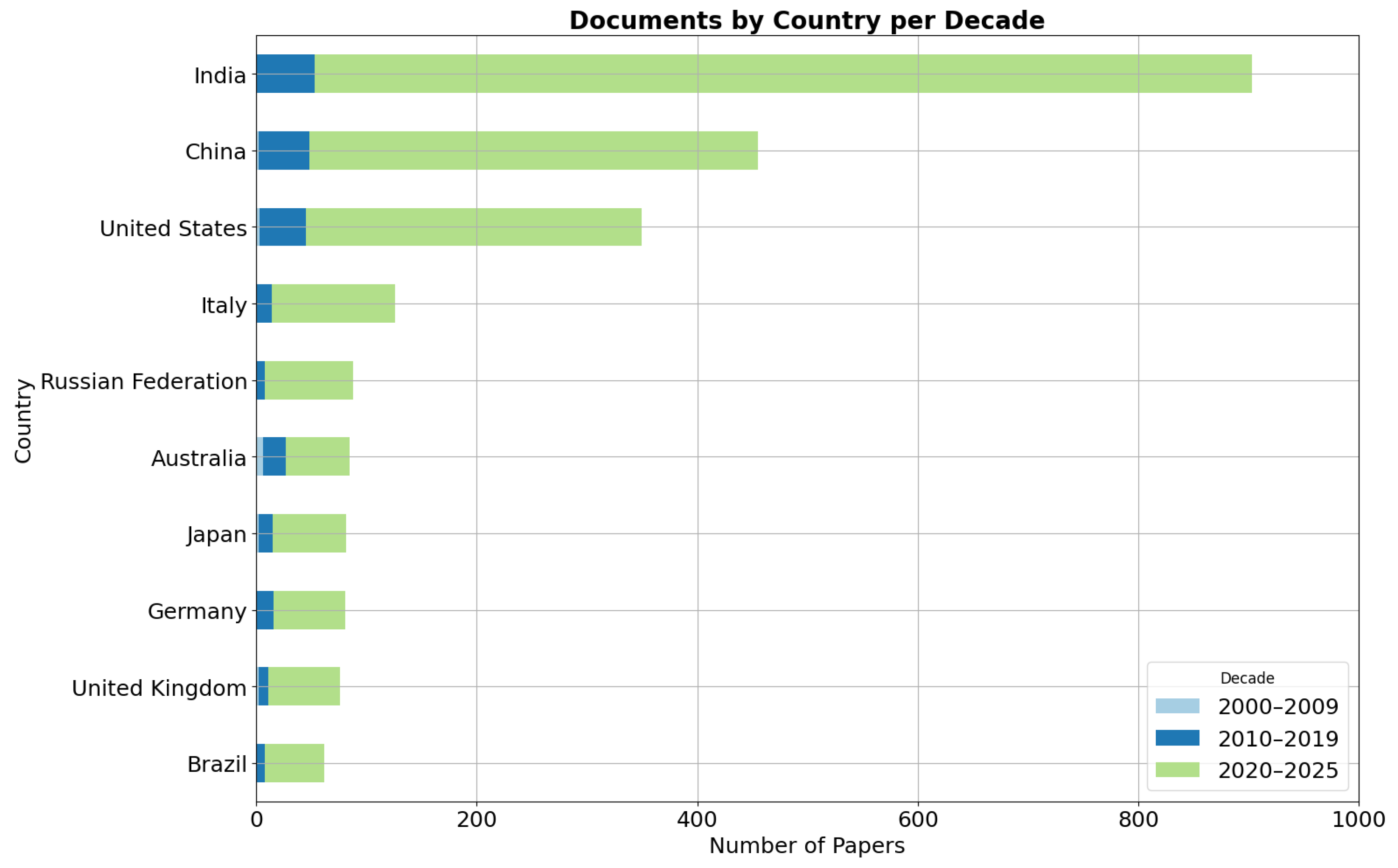

Figure 8 provides an overview of the geographical provenance of the scientific output. While cross-country comparisons based on absolute publication counts offer useful insight into global engagement with agricultural robotics and AI, such patterns may also reflect broader differences in national research ecosystems. A full normalisation against disciplinary publication volumes (e.g., Computer Science, Engineering, Mathematics, Agricultural and Biological Sciences) would require carefully harmonised, country-level scientometric baselines. However, these baselines are not directly comparable across nations due to structural differences in research funding, disciplinary emphasis, publication culture, and indexing practices. As a result, such normalisation—while informative—may introduce interpretive biases rather than resolving them in a meaningful way. For these reasons, the present study focuses on descriptive indicators as a first-order approximation of geographical trends, which remain valuable for highlighting where research activity is concentrated and how it aligns with broader agricultural, economic, and policy contexts. A more extensive normalisation framework represents a promising direction for future work, especially in studies specifically aimed at modelling cross-country research intensity.

Interestingly, India emerges as the leading contributor in terms of document count, followed by China and the United States. This result highlights a shift in the traditional dominance of Western research hubs, with Asian countries, particularly India, showing strong engagement in agricultural robotics, possibly driven by domestic needs and policy incentives. Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Australia also appear among the top contributors, although with significantly lower volumes. Their presence underscores a distributed interest across different continents, each likely reflecting diverse agricultural challenges and technological strategies.

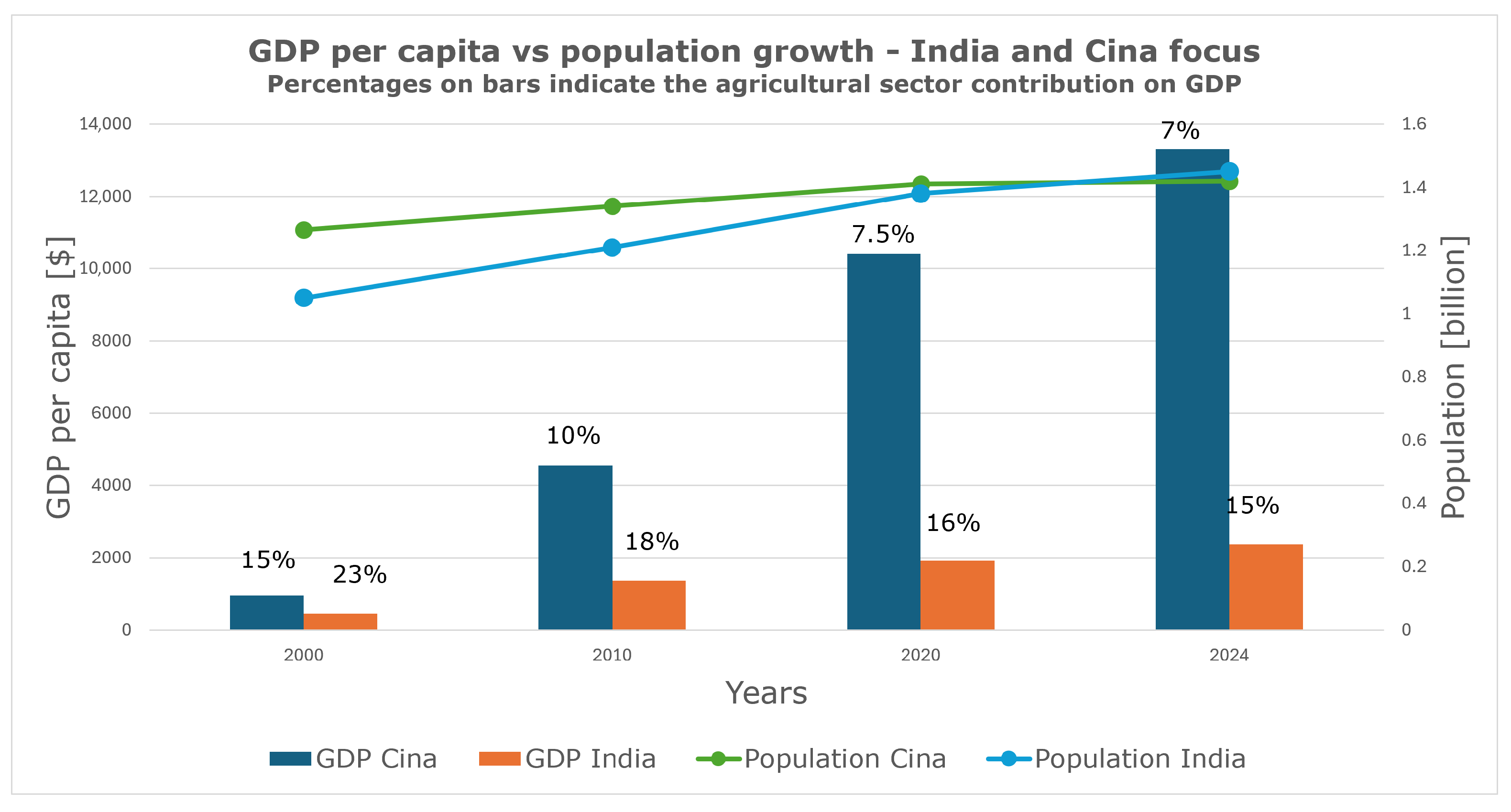

A possible reason to justify India and China as country leaders in agricultural and robotics research comes from the economic field [

32,

33].

Figure 9 shows the evolution of GDP per capita and population growth in India and China from 2000 to 2024, with a specific focus on the contribution of the agricultural sector to national GDP [

34,

35]. Despite notable economic growth in both countries, the percentage of GDP generated by agriculture has steadily declined, dropping from 15% to 7% in China, and from 23% to 15% in India over the observed period. At the same time, the population in both countries has grown, increasing the overall demand for food and agricultural output. This creates a structural imbalance: while more production is needed, fewer people are employed in agriculture, especially in India, where the shift towards service sectors has accelerated. In response to this narrowing agricultural workforce gap, both countries are increasingly investing in robotics and automation to maintain productivity and address future food demands without relying exclusively on human labour. Additional resources can be found in [

36].

Another possible reason behind the strong research productivity and investment levels observed in India and China may lie in the scale and structure of their agricultural landscapes. Both countries possess extensive, contiguous farming areas that are more amenable to the deployment of standardised robotic systems. In contrast, many European countries are characterised by highly fragmented agricultural land, often composed of small plots with diverse crops, ownership, and terrain conditions. This fragmentation presents a significant barrier to the adoption of general-purpose robotic solutions, which require spatial regularity and task repeatability to operate efficiently. As a result, large-scale economies like India and China may have a structural advantage in experimenting with and implementing automation at scale.

3.4. Funding Landscape

The final aspect of this descriptive analysis focuses on the distribution of publications by funding sponsor (

Table 2). The data reveal a clear predominance of Chinese institutions, with the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China leading the list. Together, they account for a significant share of the funded research output. European entities, such as the European Commission and the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme, also play a prominent role, confirming the strategic support for agricultural innovation within the EU policy framework. The presence of US agencies, including the Department of Agriculture and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, reflects continued investment in the automation and digitalisation of agricultural systems overseas. Brazil and the UK complete the list with their respective national funding bodies.

This funding landscape closely mirrors the country-level distribution of scientific output presented earlier: India and China not only lead in terms of document volume, but also show substantial institutional commitment to funding research in agricultural robotics and AI. These results underscore a broader strategic direction, particularly in Asia, where national investment in technology is closely aligned with policy goals aimed at modernising and securing future agricultural productivity.

3.5. Transversal Motivation

An overall positive trend in robotics and AI applied to agriculture emerges from the previous graphs, despite some fluctuations or peak years, suggesting increasing scientific interest over time. Some collateral motivation, not only related to socio-political events, can be found.

Increasing technological accessibility, both in terms of hardware and software. In recent years, the proliferation of low-cost sensors (including RTK-GPS receivers), microcontrollers (e.g., Arduino, Raspberry Pi), and open-source robotic platforms has significantly lowered the entry barrier for research and experimentation in agri-tech. At the same time, the widespread availability of open-source AI frameworks (such as TensorFlow, PyTorch, and OpenCV) has enabled researchers from a wide range of disciplines and geographies to implement advanced perception, control, and decision-making algorithms without the need for expensive proprietary tools. This democratisation of technology has been particularly impactful in emerging economies, such as India and several Latin American and African countries, where cost-effective, locally adaptable solutions are not only preferred but necessary. The combination of low-cost hardware and community-driven software development encourages bottom-up innovation and fosters context-specific solutions that can be scaled regionally. Moreover, the growing presence of interdisciplinary collaborations, linking agricultural scientists, engineers, computer scientists, and local farmers, has accelerated the prototyping and deployment of tailored robotic systems in diverse farming environments. In this scenario, accessible technology acts as both a research enabler and a practical implementation strategy, bridging the gap between academic development and field-level adoption, especially in regions where labour shortages and productivity constraints are most acute.

At the same time, the development of new systems for agricultural data acquisition and processing has further enhanced the accessibility and applicability of advanced technologies. A notable example is Agroview [

37], a cloud-based platform launched in 2019, which leverages AI to process, analyse, and visualise UAV-acquired data for precision agriculture purposes. Moreover, the increasing availability of GPU-based computing infrastructures has significantly lowered the cost and complexity of handling large-scale agricultural datasets, making high-throughput data analysis more feasible and affordable than in the past [

38].

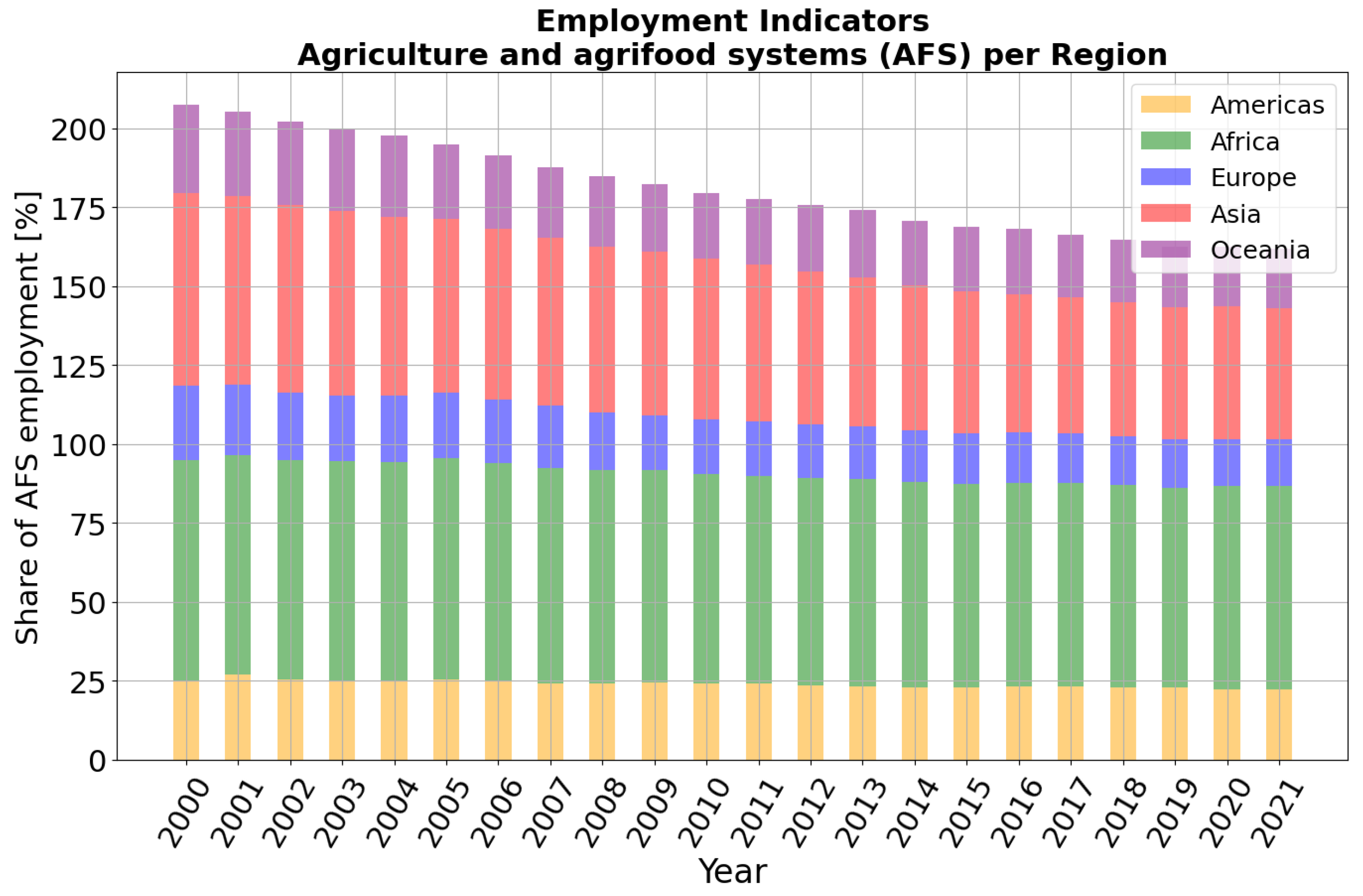

As thoroughly discussed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in [

39], the agri-food sector is currently facing significant labour and skills shortages, which risk undermining its productivity growth, resilience, and long-term sustainable development (

Figure 10).

Labour demand in the agro-food sector is highly fragmented and constantly evolving, involving a wide range of worker profiles, such as family-run operators, managers, wage earners, and various categories of casual, seasonal, and temporary workers, often recruited through migration. This is accompanied by a dual trend: a general decline in overall employment within the sector, coupled with an increasing dependence on temporary and seasonal labour. In many countries, over half of the agricultural workforce consists of hired labour, encompassing full-time, part-time, and contractual arrangements. Additional structural challenges include an ageing workforce, generally low levels of formal education, and the limited appeal of agricultural careers among young and qualified individuals. In parallel, the sector must confront broader structural issues such as labour–skill mismatches, declining generational turnover, gender and migrant inclusion, and the erosion of traditional knowledge. These challenges are further compounded by demanding working conditions and financial instability, all of which impact the sector’s attractiveness and capacity to innovate. In this complex context, the adoption of new technologies, and particularly digital and robotic solutions, holds significant promise. However, their effective implementation depends on addressing emerging needs for new knowledge and skills aligned with climate neutrality, sustainability, and resilience goals. Therefore, agricultural policy reforms aimed at improving sustainable productivity, coupled with strategic investments in Agricultural Innovation Systems, must prioritise continuous education and training to support the effective adoption of new technologies and digitalisation across the workforce.

4. Bibliometric Analysis

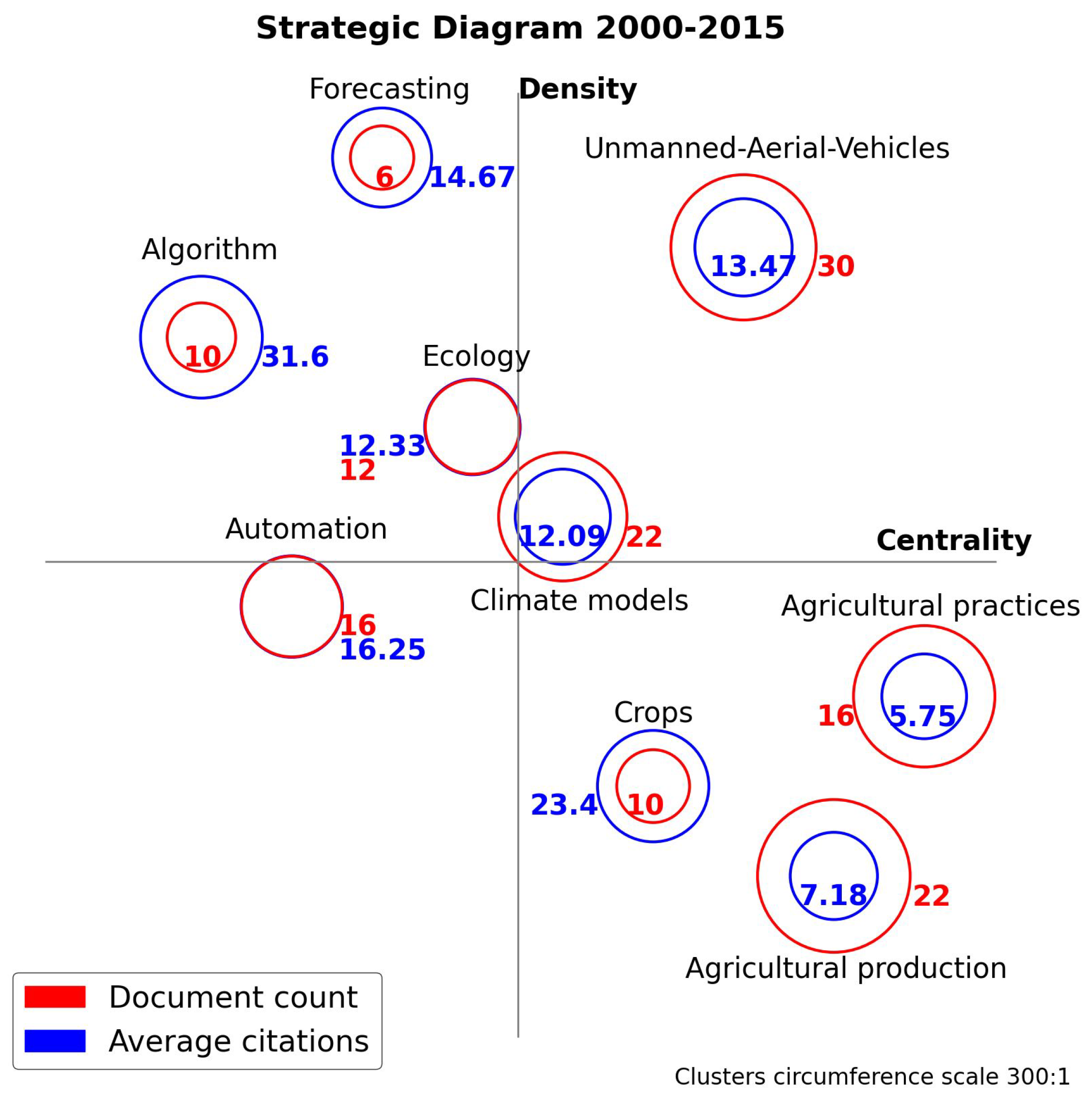

To investigate the thematic evolution of agricultural robotics and AI, a longitudinal bibliometric analysis was carried out, segmented into two distinct periods: 2000–2015 and 2016–2025. This division is supported by the descriptive findings presented earlier, which identify 2015 as a pivotal year. It marked the launch of major global initiatives—such as the FAO’s Sustainable Development Goals and the European Farm to Fork Strategy—that significantly accelerated research activity, policy focus, and investment in the agri-tech sector.

Figure 11 shows the strategic diagrams generated through SciMAT. Two visualisations are provided: one based on document count and the other on average citations, while the document count diagram highlights the volume of research output, indicating which themes are currently attracting the most attention, the average citations diagram reflects the relative scientific impact and influence of each thematic area. Starting from 2000, the distribution of clusters across all four quadrants indicates a still-fragmented research landscape, with no clearly dominant direction. Many topics appear either as isolated or basic ones, suggesting the presence of exploratory or niche studies. Nonetheless, early signs of convergence can be observed. Certain clusters already highlight areas of growing relevance, both in terms of methodology (

forecasting) and application domains (

climate models,

production,

crops). Technological tools such as

UAVs also emerge, hinting at the initial integration of sensing and data collection systems within agricultural contexts. Interestingly, a clear distinction emerges when comparing the number of documents per cluster with the average citations. Several themes with a high publication volume do not necessarily correspond to the most cited ones, reflecting a gap between productivity and scientific impact. This suggests that while some research directions were popular, others, though less prolific, may have had a stronger influence on the community’s development trajectory.

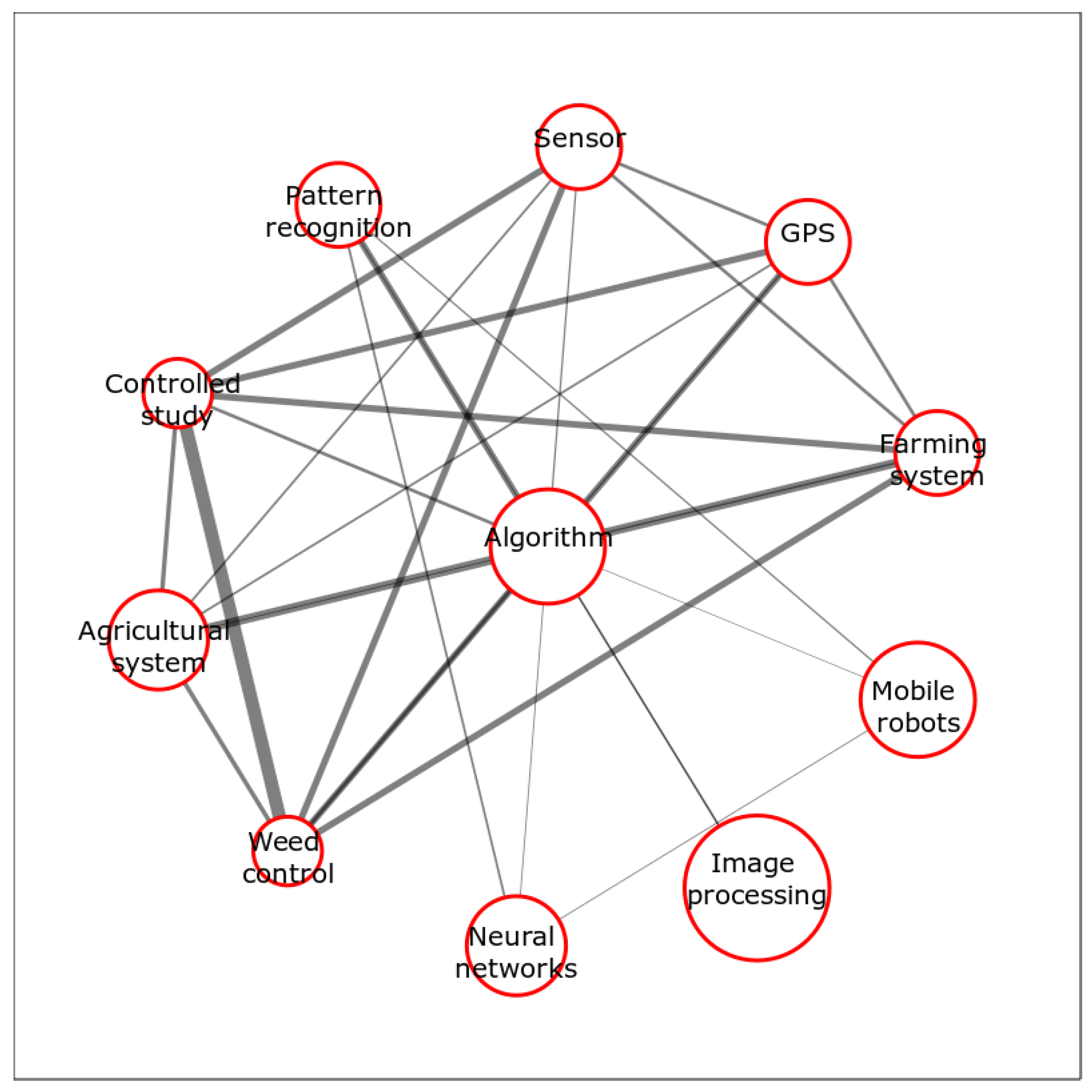

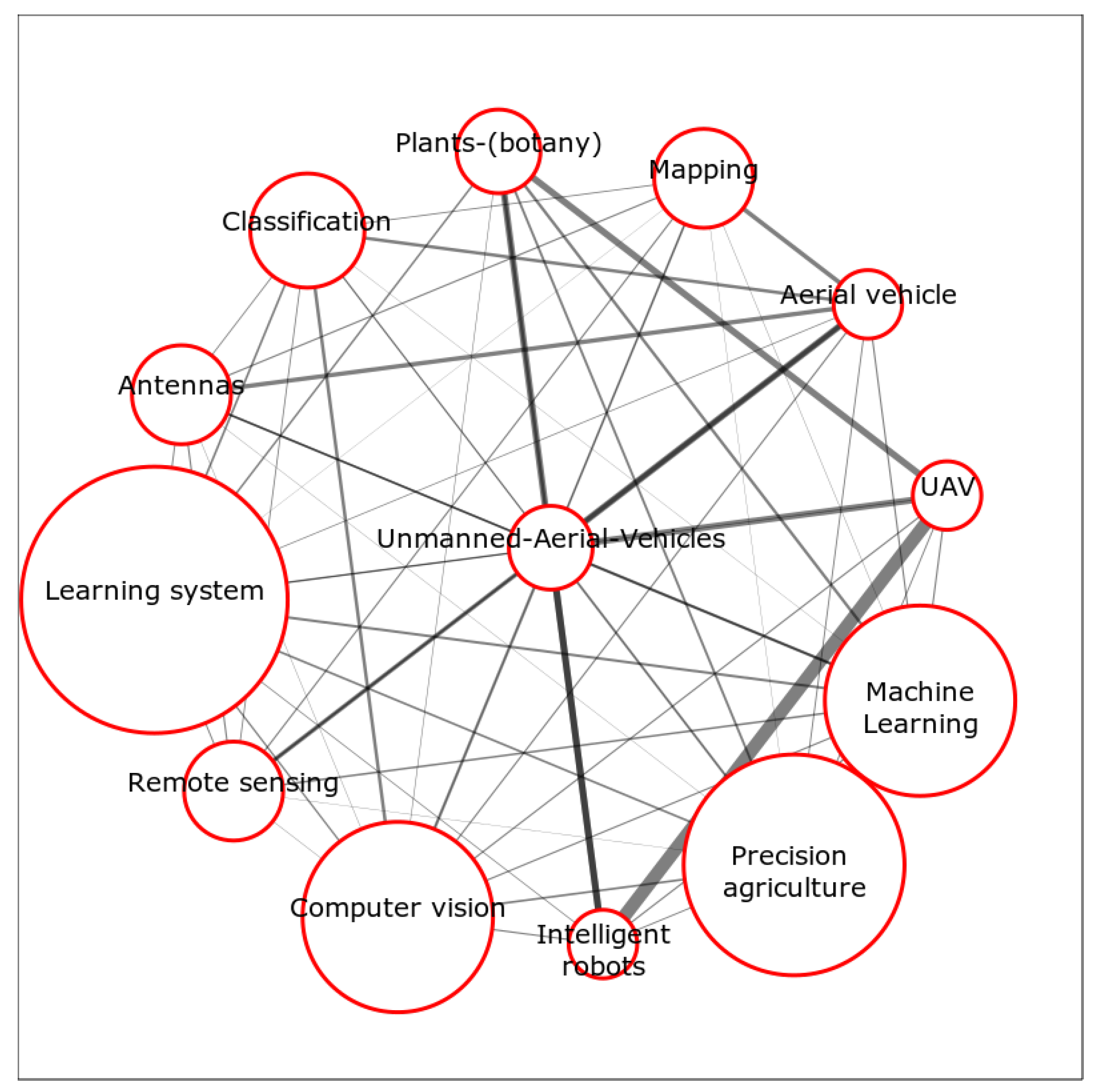

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 provide a closer look at the

Algorithm cluster (with the highest average citations) and the

UAV cluster (with the largest number of documents), respectively. Identified as the most prominent clusters in the 2000–2015 strategic diagrams, they reveal how early research in agricultural robotics struck a balance between methodological innovation and practical, field-level applications. The

Algorithm cluster connects computational methods with practical agricultural applications. Keywords such as

neural network,

pattern recognition, and

image processing suggest a strong foundation in early AI techniques. At the same time, its links to

weed control,

farming system, and

agricultural system highlight the efforts to translate these methods into real-world agronomic contexts. The presence of

sensor,

GPS, and

mobile robot reinforces this interpretation, pointing to the integration of perception, localisation, and robotics for field-level automation. The influence of this cluster is confirmed by its high citation impact, reflecting its role as a methodological backbone for subsequent developments. On the other hand, the

UAV cluster is more application-oriented. It is strongly associated with

precision agriculture,

remote sensing,

mapping, and

classification, all key topics in geospatial monitoring and decision-making. Notably, it also maintains close ties with AI-related terms like

machine learning,

computer vision, and

learning systems, indicating a shift from simple data acquisition to intelligent aerial sensing. The appearance of intelligent robots within the cluster further suggests early attempts to connect UAV platforms with broader robotic systems, highlighting their role as a bridge between sensing and automation. Together, these clusters reflect a dual trend: while algorithm development provided the computational foundation for intelligent systems, UAVs emerged as enabling platforms for scalable, data-intensive applications. This interplay between methodological advancement and practical deployment has become increasingly central to the evolution of agricultural robotics in recent years.

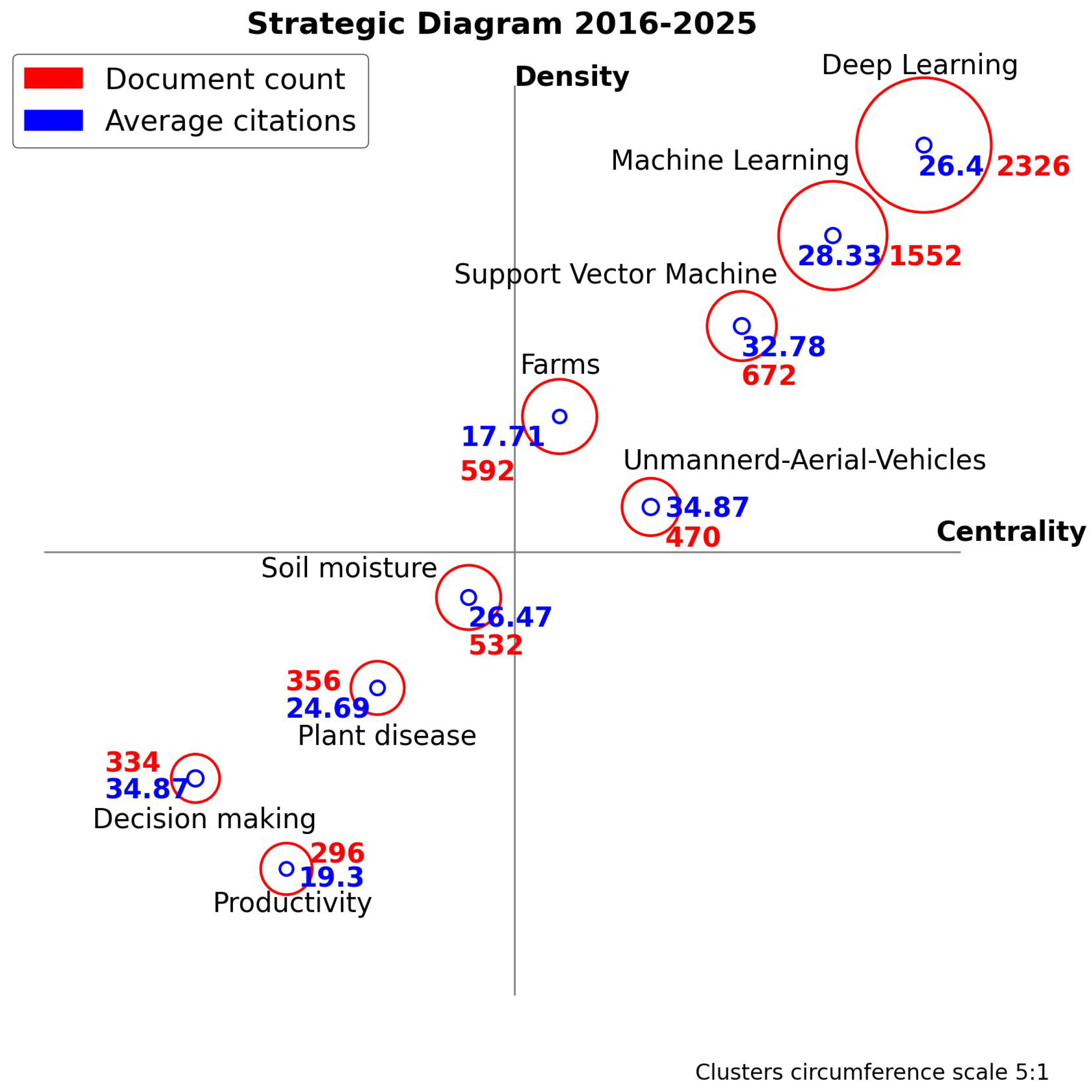

The strategic diagrams for the period 2016–2025 indicate a significant maturation of the research landscape (

Figure 14). In contrast to the fragmentation observed in the 2000–2015 period, most of the thematic clusters are now concentrated in the upper right quadrant, the area of motor themes, characterised by both high centrality and high internal development. This reflects the emergence of a more cohesive and methodologically structured field. Unsurprisingly,

Deep Learning and

Machine Learning dominate this quadrant, both in terms of publication volume and average citations. These themes have become the methodological backbone of AI applications in agriculture, replacing earlier approaches such as

Support Vector Machines, which still maintains relevance but with lower prominence. Their position as central and dense clusters highlights their dual role as both widely adopted tools and drivers of innovation across applications. The presence of

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) in the same quadrant, especially in the document count-based diagram, underscores their enduring importance as enabling technologies. However, their slightly lower density suggests that, while UAVs are widely used, their development may have plateaued, serving primarily as platforms integrated into broader AI systems rather than stand-alone research topics.

In contrast, several emerging clusters, notably soil moisture, plant disease, and productivity, are located in the lower right quadrant, where themes have a relatively high centrality but a lower internal development. These topics are increasingly relevant within the research network but remain underexplored or insufficiently consolidated. Their position indicates potential for future growth, especially as AI and sensing technologies continue to advance. Themes like Decision Making, found in the lower-left quadrant, are more peripheral and loosely connected, suggesting that despite their conceptual importance, they have not yet achieved strong methodological or interdisciplinary integration. Comparison between document count and average citation metrics uncovers, in this period of time, a divergence between methodological and application-driven research. Methodological themes such as Deep Learning and Support Vector Machines appear prominently in both diagrams, suggesting that they are not only widely studied but also widely cited, consolidating their status as foundational components of the field. In contrast, application-focused clusters like Soil Moisture, Plant Disease, and Productivity are more visible in terms of average citations but less prominent in the publication-based view, indicating the interest of the scientific community but a still lower amount of production. Additionally, several themes with moderate or low document volume, such as Decision Making, exhibit relatively high average citation scores. This points to their conceptual relevance and potential for interdisciplinary integration, despite a lower level of research activity. These clusters may represent valuable niches for future exploration and development.

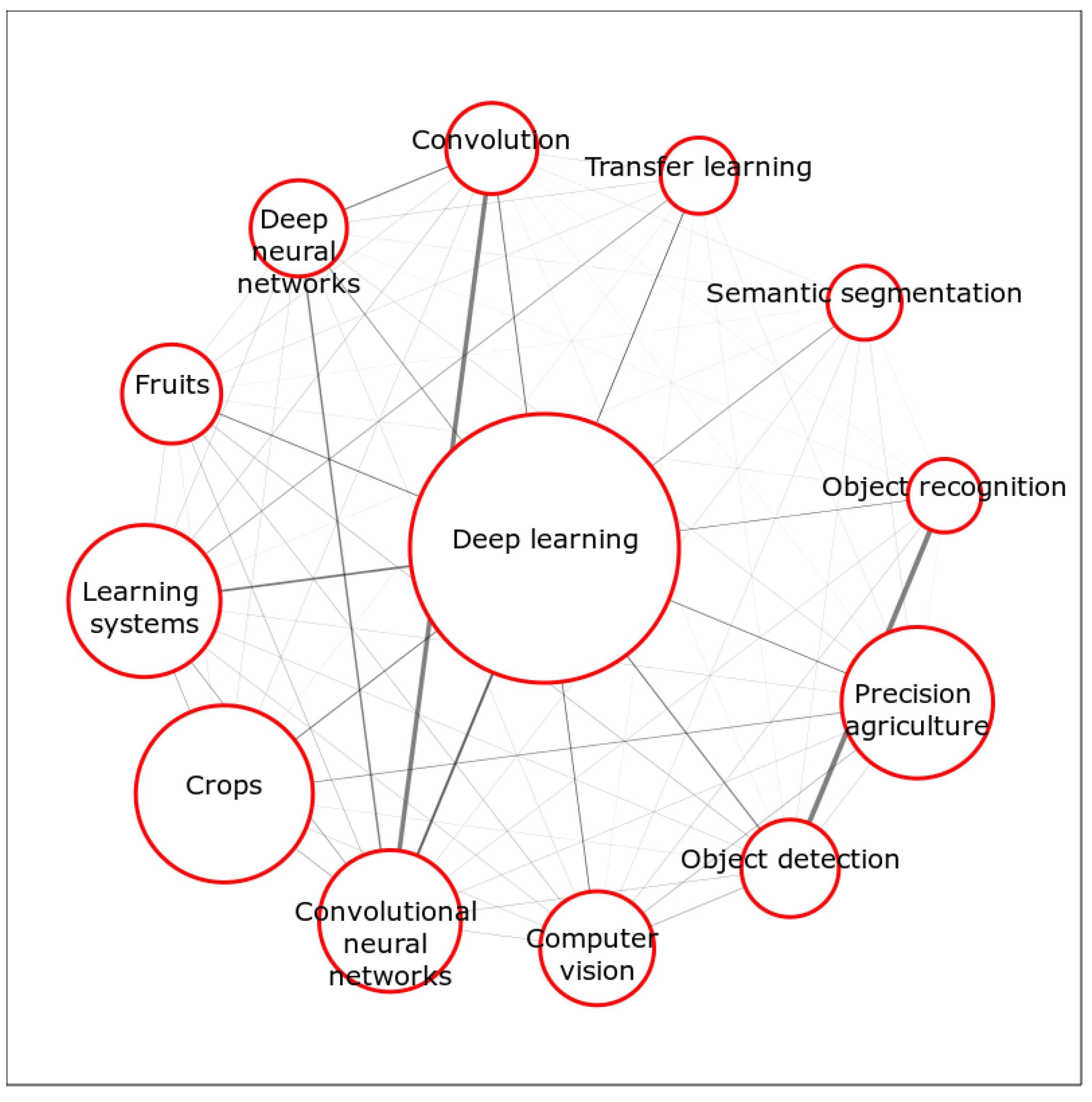

Furthermore, for this period, to complement the strategic diagrams, the internal structure of two thematically distinct yet highly relevant clusters,

Deep Learning and

Decision Making, was examined through their respective network maps (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16). The

Deep Learning cluster reveals a tightly connected and highly technological core. It is closely linked with advanced AI subfields such as

convolutional neural networks,

semantic segmentation,

transfer learning, and

object detection. These terms emphasise the sophistication of vision-based learning systems and their application in high-resolution agricultural tasks. Moreover, the presence of nodes like

precision agriculture,

fruits, and

crops demonstrates the concrete integration of deep learning techniques into crop monitoring, yield estimation, and selective harvesting. This cluster illustrates the growing reliance on data-rich, image-driven methods to address complex, real-time agricultural challenges. In contrast, the

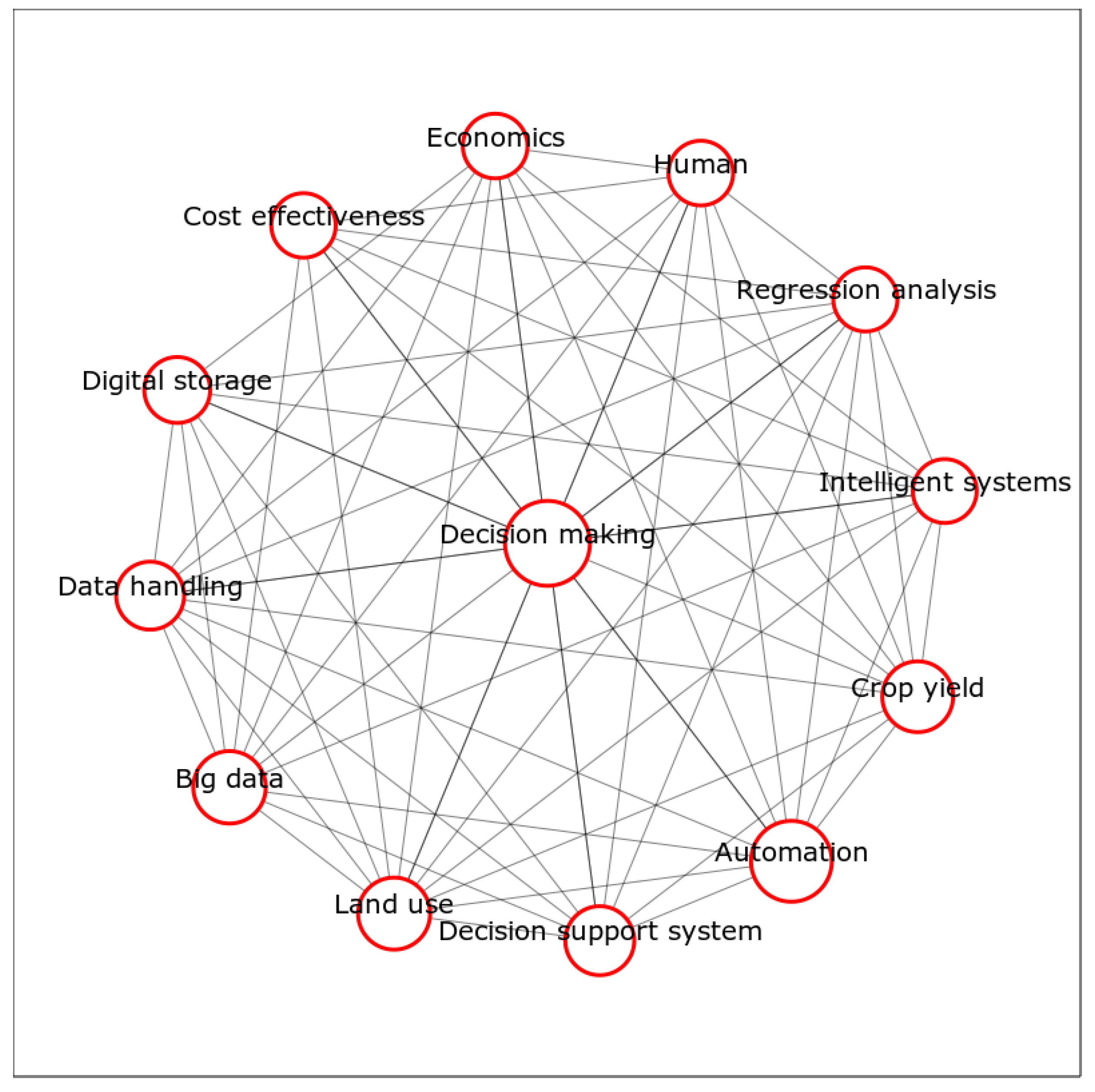

Decision Making cluster shows a broader, more interdisciplinary composition. Its connections span from agronomic applications like

crop yield,

land use, and

automation, to data management concepts such as

big data,

data handling, and

digital storage. Notably, it also incorporates terms like

cost effectiveness,

economics, and

human, reflecting the socio-technical dimensions of decision processes in agriculture. This cluster suggests that, although decision support systems remain fragmented in terms of technological integration, they constitute a crucial interface for operationalising AI tools in real-world farming scenarios, particularly in contexts requiring human oversight, resource optimisation, or economic evaluation. In parallel, the presence of “human”-related keywords within neighbouring clusters does not indicate an explicit emergence of Human-Centred AI (HCAI) as a research paradigm; rather, it reflects recurring socio-technical considerations—such as labour roles, safety constraints, and operator–system interaction—that continue to shape how agricultural technologies are conceived and deployed. These aspects point to an underlying awareness of the human dimension in agricultural robotics, without implying that current research explicitly adheres to HCAI principles such as transparency, explainability, or participatory design.

Interpreted in this way, the cluster highlights the practical need to ensure effective coordination between humans and autonomous systems, emphasising usability, oversight, and system reliability in increasingly complex, data-driven environments. When viewed together, the decision-making and human-related themes illustrate two complementary facets of agricultural AI: one centred on algorithmic and technical performance, and the other grounded in the socio-technical conditions required to integrate these systems into real agricultural workflows.

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Convergence and Current Maturity

The longitudinal bibliometric analysis highlights a clear evolution in the field of agricultural robotics and AI. In the early period (2000–2015), the research landscape appeared fragmented, with themes distributed across all four strategic quadrants, indicating exploration, low thematic cohesion, and emerging directions. By contrast, the 2016–2025 diagrams show strong consolidation around motor themes such as deep learning, machine learning, and UAVs, suggesting the emergence of a stable core supported by methodological robustness and technological feasibility. Cluster network analyses confirmed this trend: topics such as precision agriculture, image processing, and convolutional neural networks coalesced around deep learning, while decision making expanded toward interdisciplinary domains involving economics, data handling, and automation. This dual convergence reflects the field’s growing balance between algorithmic depth and system-level integration.

The VOSviewer keyword co-occurrence map presented in

Figure 17 offers a complementary global perspective to the previously discussed findings by visualising keyword relationships across the entire dataset. The analysis resulted in four main clusters, each representing a distinct thematic area within the agricultural robotics and AI research landscape.

Methodological cluster—Forecasting (red): this cluster centres on the application of machine learning techniques for predictive modelling in agriculture. It includes keywords such as machine learning, forecasting, and learning systems. Research in this area focuses on developing algorithms to predict crop yields, weather patterns, and pest outbreaks, thereby aiding in decision-making processes for farmers and agricultural stakeholders.

Methodological cluster—Perception (blue): this cluster highlights the integration of deep learning methods with computer vision technologies. Key terms include deep learning, computer vision, semantic segmentation, and object detection. Studies in this cluster aim to enhance the ability of machines to interpret visual data, enabling tasks like automated harvesting, plant disease detection, and monitoring of crop health through image analysis.

Application-focused cluster (green): this cluster emphasises the role of technology in optimising agricultural practices. It encompasses keywords such as precision agriculture, Internet of Things (IoT), farm management, and crops. Research here focuses on utilising IoT devices and data analytics to monitor and manage farming operations more efficiently, leading to increased productivity and sustainability.

Learning System and Transfer Learning (yellow): this cluster delves into advanced neural network architectures and their adaptability. This area investigates how pre-trained models can be leveraged and adapted to agricultural tasks or even serve as repositories of ecosystem-level knowledge. By minimizing the need for extensive datasets and high computational demands, these models facilitate the deployment of AI solutions across diverse farming environments, enhancing scalability and accessibility.

5.2. Gaps and Opportunities

While the bibliometric analysis confirms that agricultural robotics and AI research have reached a degree of thematic maturity, especially in areas such as perception, data analysis, and remote sensing, it also uncovers important gaps that limit the field’s capacity to deliver fully autonomous systems. In particular, the current literature lacks emphasis on the full integration of components required for true robotic autonomy in agricultural environments.

To operate independently in the field, a robot must possess a combination of capabilities that extend far beyond isolated functions such as object detection or path planning. These include:

perception: the ability to sense and interpret complex, variable environments, often relying on vision, depth, spectral, and tactile inputs;

manipulation: the capacity to interact physically with deformable, fragile, and biologically variable materials (e.g., fruits, stems, soil);

control: precise actuation and coordination of movement under uncertain or changing conditions;

situational awareness: understanding context, time, and task progress within open-ended scenarios;

adaptability: real-time learning or adjustment in response to environmental feedback;

system-level integration: the orchestration of all the above in coherent, reactive, and mission-driven behaviours.

Despite the growing presence of topics like deep learning, precision agriculture, and remote sensing, especially evident in both SciMAT (

Figure 14) and VOSviewer (

Figure 17), themes such as

robot manipulation,

dynamic control, or

long-term autonomy are underrepresented or missing entirely. The relative absence of clusters related to decision feedback, embodied interaction, or adaptive execution suggests that most research still targets static, perception-centric scenarios rather than fully autonomous, embodied agents. This is especially critical in agriculture, where autonomy is not a luxury but a necessity. Agricultural environments are inherently dynamic: crops grow, weather patterns shift, terrain conditions change, and tasks vary from season to season, requiring adaptive and resilient AI systems capable of operating under continuous variation. Unlike controlled industrial settings, the farm is a living system. Robots must be able to handle the unpredictability of biological processes and operate under conditions where human intervention may not be viable, whether due to labour shortages, scale, or remoteness. Full autonomy thus becomes the key to enabling cost-effective, scalable solutions that align with both productivity and sustainability goals.

From a strategic perspective, this gap in the literature highlights a significant opportunity. The development of systems capable of spatio-temporal reasoning, closed-loop decision-making, and adaptive multi-modal control represents the next frontier in agricultural robotics. Bridging this gap will also contribute directly to several SDGs, including SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 8 (Decent Work), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), by enabling autonomous tools that can function reliably in real-world, labour-constrained, and resource-sensitive contexts.

In conclusion, future research must move beyond individual components, such as classification models or weeding mechanisms, and focus instead on the orchestration of autonomy: systems that can perceive, act, adapt, and complete agricultural tasks over time, independently and sustainably. These are the systems that will unlock the real transformative potential of robotics in agriculture.

5.3. Alignment with the FAO Sustainable Development Goals

To contextualise the results of the bibliometric analysis within a broader societal and policy-driven framework, the identified research themes were mapped against the SDGs as outlined by the FAO. This mapping allows for a structured interpretation of how the most recurrent scientific efforts, both methodological and application-oriented, contribute to global priorities in food security, environmental sustainability, and rural development.

The SDGs serve as a benchmark to assess not only what technologies are being developed, but why they matter. For example, research clusters focusing on precision agriculture, deep learning, and UAV-based sensing respond directly to the needs outlined in SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), by enabling more efficient resource use, reducing losses, and improving yields. Similarly, studies on decision support systems, climate forecasting, and soil moisture sensing align with SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 15 (Life on Land) by addressing resilience and sustainable land use.

Table 3 summarises these correspondences.

This transposition demonstrates that the current scientific focus in agricultural robotics and AI not only reflects internal technical evolution, but also converges with high-level global policy objectives. It reinforces the idea that technological innovation must be guided by impact-driven strategies that support inclusive, sustainable and resilient food systems.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

This systematic bibliometric review provides a consolidated, evidence-based account of how artificial intelligence and robotics have evolved within agricultural research over the past 25 years. The longitudinal analysis highlights a clear methodological consolidation around deep-learning perception, UAV-enabled sensing, and data-driven decision systems, which currently form the core technological pillars of agricultural automation. At the same time, the low-density and high-centrality position of themes such as manipulation, multimodal sensing, soil–crop interaction, and adaptive autonomy reveals persistent gaps that prevent the field from advancing toward fully autonomous and embodied systems capable of operating reliably in open, dynamic agricultural environments.

A distinctive contribution of this study lies in framing these scientific developments within the broader landscape of the FAO Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By mapping technological trends against global priorities such as food security (SDG 2), resource efficiency and responsible production (SDG 12), climate resilience (SDG 13), and decent work (SDG 8), the analysis highlights how current research trajectories both support and are shaped by sustainability-oriented agendas. In particular, the emphasis on perception-driven monitoring aligns with the need for precision agriculture and reduced input use, while the gaps identified in manipulation, autonomy, and system-level integration point to technological bottlenecks that must be addressed to enable scalable, sustainable agri-food systems. In this sense, the bibliometric mapping not only synthesises scientific activity but also clarifies how the research community is—explicitly or implicitly—positioning itself in relation to global sustainability challenges.

Building on these insights, the findings offer a data-informed framework to support research planning, funding prioritisation, and interdisciplinary collaboration. As agricultural robotics becomes increasingly critical in addressing global sustainability and food security challenges, there is an urgent need for coordinated efforts aimed at delivering scalable, adaptive, and socially aligned technological solutions (

Figure 18).

As a systematic review grounded in bibliometric data, the synthesis reflects the scope and structure of publications indexed in Scopus, while the screening workflow and bias-mitigation procedures were designed to ensure robustness, the analysis does not incorporate full-text interpretation and therefore cannot capture fine-grained methodological nuances. Additionally, cross-country interpretations remain sensitive to structural differences in national research ecosystems. Future work should explore complementary normalisation strategies, expand the analysis to include full-text mining of methodological content, and investigate how agricultural, environmental, and socio-economic variables shape research trajectories. Extending science-mapping analyses to subdomains such as soft robotics, reinforcement learning for agricultural control, or collaborative human–robot systems would further deepen the understanding of how autonomous technologies can support sustainable and resilient agricultural systems.