1. Introduction

Gait impairments caused by neurological conditions and aging significantly limit independent mobility and daily functioning [

1,

2,

3]. Wearable lower-limb exoskeletons have therefore attracted growing interest as an assistive and rehabilitative technology, with prior studies demonstrating their ability to reduce muscle activation, improve step-to-step stability, and enhance functional walking capacity when properly tuned to the user [

4,

5,

6,

7].

HIL optimization has become a central paradigm in exoskeleton research, in which the human user is actively incorporated into the control loop. By presenting different control strategies over successive gait cycles and evaluating the resulting energetic response, HIL algorithms iteratively converge toward personalized assistance profiles. This step-level adaptation relies critically on the ability to assess metabolic cost during walking, as reductions in energy expenditure serve as the primary indicator of improved assistance. Consequently, accurate and responsive metabolic evaluation is essential for enabling optimization in practical exoskeleton applications [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Indirect calorimetry, which analyzes oxygen uptake and carbon dioxide production, is regarded as the gold standard for estimating metabolic cost. However, despite its accuracy, metabolic measurement remains impractical for routine exoskeleton optimization. Indirect calorimetry requires specialized respiratory equipment, controlled laboratory environments, and multi-minute stabilization periods for each condition, making it unsuitable for rapid parameter tuning or deployment in daily use settings [

10,

11,

15]. These limitations have motivated the use of wearable physiological and kinematic sensors, such as accelerometry, heart rate, and surface electromyography (sEMG) [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Among these modalities, sEMG is the most commonly used physiological signal, as it reflects muscle activation closely related to metabolic cost [

24].

Most existing studies employ regression-based methods that map the features directly to continuous metabolic values. Prior regression-based studies [

16,

18,

21] have similarly reported moderate prediction accuracy with RMSE values typically ranging from

to

, reflecting the inherent difficulty of estimating absolute metabolic cost from wearable signals. Although these approaches capture general relationships, their performance is severely limited by inter-subject variability caused by differences in muscle physiology and electrode placement. As a result, models trained on one group of subjects often generalize poorly to new users, restricting real-world applicability.

To address these limitations, this study reformulates the estimation of energy expenditure as a contrastive classification task. The proposed approach directly compares two control laws applied to the same subject and determines which one results in lower energy expenditure. In practice, accurately predicting absolute metabolic cost from wearable signals is extremely challenging. Respiratory gas analysis requires long averaging windows and is affected by measurement noise and individual physiological differences, which leads to large variability in absolute values even under similar conditions. By contrast, when two assistance strategies are sufficiently different, the relative ordering of their metabolic costs is typically more stable than the exact numerical estimates. For exoskeleton optimization, the key question is therefore not the precise energy expenditure in watts, but rather which of two candidate control laws yields lower effort for the user. Motivated by this observation, we reformulate the problem as a pairwise classification task, instead of regressing absolute metabolic values, the model learns to decide which control law is better, a formulation that is inherently more robust to noise and inter-subject variability.

A Siamese network [

25] architecture (which two identical subnetworks with shared weights process paired sEMG inputs to extract comparable feature representations) is adopted to extract discriminative sEMG features under different control strategies, enabling robust comparative evaluation, while the step-level nature of exoskeleton optimization ensures that the deep model’s millisecond-level inference latency is more than sufficient for practical deployment.

To further enhance generalization across individuals, this study introduce an unsupervised domain adaptation mechanism. A Dual Adversarial Adaptive Optimization Strategy (DAAOS) is proposed to promote the learning of domain-invariant features by jointly employing domain confusion and maximum classifier discrepancy.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

We reformulate exoskeleton energy expenditure evaluation as a pairwise contrastive classification problem. This task formulation provides a more robust and interpretable criterion for control-law optimization and has not been explored in prior metabolic estimation studies.

We integrate domain-adversarial learning and classifier-discrepancy minimization into a Siamese architecture operating on paired sEMG representations, to reduce inter-subject variability and enhance model generalization.

The proposed approach is validated on both public and locally collected datasets, achieving higher accuracy than conventional regression-based methods and demonstrating its potential as a robust objective function for exoskeleton optimization in real-world applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

The goal of this study is to evaluate exoskeleton control laws using surface electromyography (sEMG) signals in a way that is robust to inter-subject variability. Given two candidate strategies, the objective is to determine which induces lower physiological effort, providing a binary decision for high-level optimization.

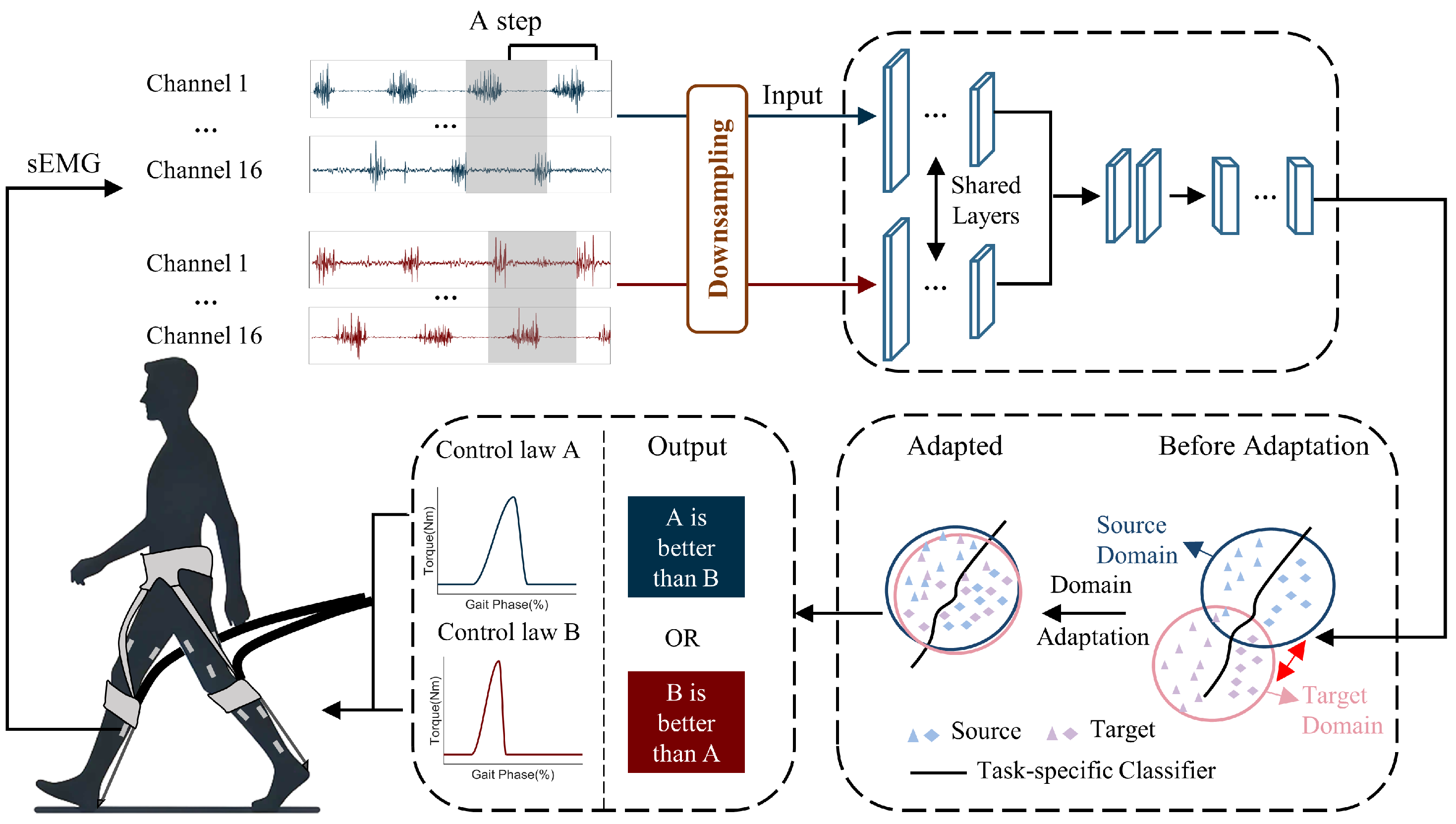

To achieve this, a Control Laws Evaluation Strategy with Domain Adaptation (CLES-DA) was developed. It consists of a Control Laws Evaluation Network (CLEN) and a Dual Adversarial Adaptive Optimization Strategy (DAAOS). CLEN performs comparative evaluation of paired sEMG signals, while DAAOS aligns feature distributions across individuals to ensure generalization. An overview of the workflow is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Label Construction Based on Energy Expenditure

Energy expenditure serves as a fundamental indicator of user effort and system efficiency in exoskeleton studies. This paper introduces a contrastive classification model that identifies the superior strategy by analyzing differences in sEMG responses under two distinct control laws.

To construct classification labels, metabolic data were collected using indirect calorimetry. Carbon dioxide production and oxygen consumption were recorded and substituted into the Brockway equation to calculate metabolic power (in watts). Since metabolic signals transient dynamics during condition transitions, a first-order dynamic model was applied to estimate the steady-state metabolic rate. The discrete-time formulation is given as:

where

i denotes the breath index,

is interval between consecutive breaths,

represents the calculated metabolic rate, and

is the time constant, expressed in seconds, (set to 42 following prior studies [

26]). By recording

and

over a 2-min interval, this iterative process yields an accurate estimate of the metabolic rate, with an average error of approximately 4% compared to steady-state measurements [

10].

After estimating the metabolic associated with each control law using the respiratory measurements, we converted these continuous values into binary labels for pairwise classification. For each comparison, the two metabolic estimates were treated as ground-truth indicators of walking effort. If the first control law resulted in lower metabolic cost than the second, the corresponding pair was labeled as 1; otherwise, it was labeled as 0. Trials in which the two control laws produced nearly identical metabolic values were excluded, as such cases do not provide a meaningful preference signal and would introduce ambiguity into the training labels.

2.3. Control Laws Evaluation Strategy Based on Domain Adaptation (CLES-DA)

The Control Laws Evaluation Strategy based on Domain Adaptation (CLES-DA) aims to provide accurate and robust evaluation of exoskeleton control laws across subjects. As shown in

Figure 2, the framework comprises two key modules: the Control Laws Evaluation Network (CLEN), which performs comparative evaluation of pairwise EMG signals, and the Dual Adversarial Adaptive Optimization Strategy (DAAOS), which enhances generalization across subjects by mitigating distribution shifts.In this study, distribution shifts denote the differences in sEMG and metabolic patterns across subjects and sessions, caused by variations in muscle activation, signal amplitude, electrode placement, and physiology. These mismatches between source and target data can impair model generalization if left unaddressed.

2.3.1. Control Laws Evaluation Network (CLEN)

At the core of CLES-DA is CLEN, a Siamese architecture that processes paired sEMG signals and outputs a comparative judgment of which control law yields lower energy expenditure.

The Feature Generator (G) extracts deep, shared representations of sEMG image input which constructed from one complete gait cycle recorded across 16 channels. As shown in

Figure 3, it consists of six convolutional layers with

filters, each followed by batch normalization and a softsign activation. The number of filters for each convolutional layer is 16, 16, 32, 32, and 64, respectively. Max-pooling layers are inserted after the first three convolutional blocks.

The extracted feature embeddings are subsequently fed into the Main Classifier (C1), implemented as a three-layer fully connected network. The two hidden layers contain 100 neurons, and the output layer comprises two neurons corresponding to the binary classification of control laws. ReLU activation, dropout, and L2 regularization are employed to alleviate overfitting. The classification task is optimized using the cross-entropy loss function:

where

and

represent the true and predicted labels, respectively.

2.3.2. Dual Adversarial Adaptive Optimization Strategy (DAAOS)

Although the Control Laws Evaluation Network (CLEN) effectively compare control strategies, its generalization capability is limited by the inter-subject variability of sEMG signals. To mitigate this limitation, DAAOS integrates adversarial domain adaptation [

27] and maximum classifier discrepancy (MCD) [

28] to align source and target feature distributions.

Within this framework, a Domain Discriminator (D) is introduced to determine whether extracted features originate from the source or target domain. To encourage the Feature Generator (G) to learn domain-invariant representations, the discriminator is trained adversarially through a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) [

29]. The GRL forwards inputs unchanged during the forward pass but reverses the gradients sign during backpropagation. As a result, G is penalized whenever D successfully distinguishes the domain, progressively driving G to produce features that confuse the discriminator and thereby minimize domain-specific biases.The discriminator loss is expressed as:

where

and

denote the true and predicted domain labels, respectively. The GRL serves as the core mechanism for domain confusion. It does not contribute to the forward propagation process. It is defined as:

During backpropagation, the gradient of GRL is negated and scaled by a tradeoff parameter

:

Complementing this adversarial alignment, the Maximum Classifier Discrepancy (MCD) is employed to expose discrepancies in decision boundaries between classifiers. Specifically, a second classifier (C2), identical in structure to the main classifier (C1), is introduced to establish parallel decision boundaries. For unlabeled target-domain samples, the discrepancy between the predictions of C1 and C2 indicates regions of high uncertainty. The two classifiers are first optimized to maximize their prediction discrepancy on target-domain samples, revealing regions of uncertainty. The feature generator is then updated to minimize this discrepancy, encouraging target features to move toward regions where both classifiers agree. This adversarial process helps reduce target-domain ambiguity and improves domain alignment [

28].

where

and

denote the predicted probability distributions of C1 and C2 for the target-domain input

Through the combined effects of adversarial domain confusion and classifier discrepancy minimization, DAAOS aligns the source and target feature spaces while preserving task-relevant distinctions.

2.3.3. Training Procedure of CLES-DA

The training process of CLES-DA consists of two stages: pre-training and adaptation.

In the pre-training stage, the Feature Generator and both classifiers (C1 and C2) are trained solely on labeled source-domain data. This initialization allows the network to learns discriminative feature representations and achieves stable classification performance before domain adaptation is introduced.

In the adaptation stage, training proceeds through three iterative steps that progressively align the source and target distributions. In the first step, the network continues to minimize classification losses on labeled source data while jointly updating the feature extractor and both classifiers to preserve source accuracy.

where

,

, and

denote the parameters of G, C1, and C2 respectively.

In the second step, with the Feature Generator fixed, the two classifiers are updated to maximize their prediction discrepancy on unlabeled target samples. This step exposes regions of the target domain where decision boundaries are uncertain.

In the third step, with the classifiers fixed, the feature generator is updated to minimize the inter-classifier discrepancy on target data while simultaneously being trained adversarially against the domain discriminator.

The trade-off parameter

is scheduled to vary over time.

The training processes is implemented in Pytorch v2.3.0 and executed on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080. During the pre-training stage, the feature generator and the two classifiers were trained using only labeled source-domain data with a batch size of 200, an initial learning rate of 0.001, and 50 training epochs.

For the adaptation stage, the held-out subject was treated as the target domain. The adaptation process lasted for 80 epochs. During each adaptation epoch, a mini-batch was constructed by randomly sampling 100 labeled source-domain samples and 100 unlabeled target-domain samples (a 1:1 ratio).The detailed optimization procedure is presented in the Algorithm 1. The feature generator and classifiers were optimized using an initial learning rate of 0.001 and a dropout rate of 0.5, while the domain discriminator employed a higher learning rate of 0.1 to stabilize the adversarial optimization.

| Algorithm 1: Adaptation Stage of CLES-DA |

![Robotics 14 00187 i001 Robotics 14 00187 i001]() |

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Datasets

Two datasets were utilized to evaluate the the proposed CLES-DA framework. A public dataset obtained from the Stanford Digital Repositor [

30], was used to validate the generalization ability of the model across subjects. A local dataset was further collected to assess practical applicability.

The public dataset contained sEMG signals from six healthy subjects (four males and two females, age: years, height: m, body mass: kg). Each participant wore bilateral ankle exoskeletons and completed a 72-min walking trial on a split-belt treadmill at a constant speed of 1.25 m/s. Data were recorded across multiple sessions to support both cross-subject and cross-day evaluation. The public dataset includes sEMG recordings from both legs, with 16 channels covering major lower-limb muscles bilaterally.

The local dataset included four healthy male participants (mean age:

years, height:

m, body mass:

kg). Participants walked on a treadmill at 1.25 m/s while wearing a unilateral ankle exoskeleton (as shown in

Figure 4). A unilateral soft exoskeleton was used to provide ankle assistance during data collection. The device has a lightweight soft-structure design with a total mass below 1 kg and actuates only the ankle joint. Nine distinct control laws were implemented by varying peak time and peak force parameters (

Table 1). Sixteen sEMG channels (tibialis anterior, soleus, medial and lateral gastrocnemius, rectus femoris, vastus medialis, biceps femoris, and semitendinosus) were recorded using the Trigno Wireless System (Delsys Inc., Natick, MA, USA). A COSMED K5 wireless metabolic (COSMED, Rome, Italy) was used to measure breath-by-breath

and

. Metabolic power was computed using the Brockway equation, and the resulting energy expenditure values were used to generate pairwise labels.

Local experiments were conducted over three separate days. The first day served as an adaptation session, allowing participants to familiarize themselves with the exoskeleton and experienced different assistance strategies without data collection for analysis. The second and third days were designated as formal data acquisition sessions, during which sEMG and metabolic data were recorded under the each control laws. This multi-day protocol ensured adequate subject adaptation and introduced both cross-day and cross-subject variability.

3.2. Data Processing

Raw sEMG signals were filtered using a 50 Hz notch filter to remove power-line interference and a 20–450 Hz fourth-order Butterworth band-pass filter to reduce motion artifacts and high-frequency noise. The sEMG signals were then segmented into individual gait cycles based on heel-strike events detected by inertial sensors. Each gait cycle was downsampled to 600 points to ensure consistent temporal resolution. For model inputs, the processed sEMG signals from 16 channels were arranged into tensors of size , with each tensor representing one gait cycle uder a specific control law.To construct paired sEMG samples, gait cycles were matched according to their sequence order across conditions (e.g., the first step in Condition 1 paired with the first step in Condition 2). When two conditions contained different numbers of cycles, the condition with fewer cycles determined the usable length, and extra cycles in the longer condition were discarded. This ensured that all pairwise comparisons were based on corresponding gait cycles.

Ground-truth labels were derived from steady-state metabolic rates estimated using indirect calorimetry and a first-order dynamic model. For each pair of control law, a binary label was assigned based on the relative difference in energy expenditure. A value one if the first law resulted in lower expenditure, zero otherwise. Equal conditions were excluded to maintain balanced classes.

3.3. Experimental Design

The evaluation protocol was designed to test both cross-subject and cross-session generalization. For the public dataset, recordings from the second experimental day were used to perform leave-one-subject-out cross-validation. In each iteration, data from five participants were assigned to the source domain for training, while the remaining participant served as the unseen target domain. This procedure was repeated until every participant had been used once as the target, providing a comprehensive assessment of cross-subject performance.

To better reflect realistic deployment scenarios, additional experiments were conducted by combining cross-day and cross-subject conditions. Specifically, training was performed on Day 2 data from five participants, and testing was carried out on the Day 3 data of a previously unseen participant. This configuration jointly captured inter-individual variability and session-to-session differences.

For the local dataset, we primarily evaluated the adaptation stage of the training process. The feature extractor and classifiers were first pre-trained on the public sEMG dataset. Subsequently, a leave-one-subject-out protocol was applied to the local dataset. Specifically, second-day recordings from three participants were aggregated to form the labeled source domain, while approximately nine minutes of third-day data from a fourth participant were used as unlabeled target-domain samples for adaptation. The model then underwent the same adaptation procedure as in the adaptation stage, allowing us to assess its ability to transfer from publicly learned representations to new individuals recorded crossing subjects and sessions.

The performance of three methods were compared in this paper:

- (1)

CLES-DA, the method proposed in this study was designed to evaluate the control laws effectively.

- (2)

CLEN without unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA),a baseline model employing the CLEN architecture but excluding UDA modules, used to quantify the contribution of domain adaptation to overall performance.

- (3)

Energy Expenditure Prediction (EEP), a neural network-based method that directly models the relationship between sEMG signals and energy expenditure. Specifically, the EEP model adopts a single-branch convolutional architecture that is consistent in depth with the feature extractor used in CLEN but operates on sEMG data from only one control law at a time and outputs continuous estimates of metabolic energy expenditure.

The feature extractor consists of six convolutional layers with 3 × 3 kernels (16, 16, 32, 32, 64, and 64 filters), each followed by batch normalization and a softsign activation, with max-pooling applied after the first three convolutional blocks. The extracted features are fed into a three-layer fully connected regressor with ReLU activations, dropout (0.5), and L2 regularization. The model is trained using mean squared error (MSE) loss, optimized by stochastic gradient descent (momentum = 0.9) with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and the same exponential decay schedule used in CLEN. All hyperparameters were independently tuned using source-domain validation to ensure a fair comparison. To compare equitably with other methods, the predicted and measured metabolic values were post-processed using the same steady-state estimation procedure described in the data preprocessing section.

3.4. Results

The experimental results are presented in three parts. First, the baseline performance of the regression-based Energy Expenditure Prediction (EEP) method is analyzed to provide a reference for subsequent comparisons. Next, a comparative evaluation among CLEN, EEP, and CLES-DA is presented, demonstrating the advantages of reformulating the problem as a classification task and integrating domain adaptation. Finally, the feature distributions before and after domain adaptation are visualized using t-SNE, providing qualitative insights into how the proposed framework mitigates domain shifts and enhances generalization.

All reported results correspond to target-domain evaluations, meaning that models were tested exclusively on data from unseen individuals or from different sessions (cross-subject and cross-day conditions). This setup directly reflects the practical scenario of deploying an exoskeleton on new users, where inter-subject variability and session-to-session differences present major challenges.

3.4.1. Energy Expenditure Erediction (EEP) Baseline

The regression-based EEP method predicted continuous metabolic values for each gait cycle. On the public dataset, the model achieved an average error of 9.7% and an RMSE of . Subject specific errors varied considerably, with the best performing subject achieving 6.1% error (0.40 RMSE) and the worst-performing subject reaching 13.8% error (0.91 RMSE).

To contextualize these results,

Table 2 compares our EEP performance with previously reported metabolic prediction errors in the literature. The average percentage error (9.7%) and RMSE (

) observed in our study fall within the range of values commonly reported for regression-based metabolic estimation. For example, the method in [

21] achieves an RMSE of

, while [

18] reports approximately

and [

16] reports

. Such variation is typical and largely attributable to differences in sensor modalities, treadmill protocols, subject, and window-averaging strategies across studies.

Although the EEP approach effectively captured general trends in energy expenditure across conditions, its predictive accuracy exhibited high variability among individuals. Visual inspection of representative subjects (

Figure 5) revealed that the predicted curves followed the overall shape of measured metabolic data, but failed to replicate finer local fluctuations.

Beyond regression accuracy, the continuous outputs were further post-processed into pairwise comparisons between two control laws, converting the predictions into binary labels indicating which strategy produced lower energy expenditure. Under this formulation, the EEP method achieved a classification accuracy of 58.5 ± 5.3%. This result further illustrates the limitations of direct regression approaches, as the ability to rank control strategies remained low compared with classification-based frameworks.To further characterize subject-wise variability,

Table 3 reports the per-subject accuracies of EEP, CLEN, and CLES-DA under the LOO protocol. Across all six subjects, EEP consistently exhibited the lowest performance, confirming that regression-based metabolic estimation is not sufficiently reliable for ranking control laws on a subject-independent basis.

3.4.2. Comparative Performance of CLEN, EEP, and CLES-DA

The proposed comparative evaluation framework demonstrated clear advantages over direct regression methods. On the public dataset (

Figure 6), the CLEN without domain adaptation achieved an accuracy of

, outperforming the EEP baseline (

).

Further performance gains were achieved when domain adaptation was incorporated. The complete CLES-DA framework reached an accuracy of , representing a statistically significant improvement over both CLEN and EEP. This improvement was consistent across subjects, as reflected by the reduced variance in classification accuracy. These findings highlight the importance of the Dual Adversarial Adaptive Optimization Strategy in mitigating domain shifts arising from differences in muscle properties, electrode placement, and walking patterns.

To assess the statistical significance of these improvements, paired comparisons were performed across the six subjects using the per-subject accuracies summarized in

Table 3. Compared with CLEN, CLES-DA achieved a mean improvement of 13.27%, and this difference was statistically significant (

; 95% CI: [9.55, 16.99]). Relative to EEP, the improvement was even larger (19.12 %), also reaching statistical significance (

; 95% CI: [13.99, 24.24]). These findings indicate that the gains obtained by CLES-DA are not only numerically higher but also consistently observed across all subjects.

Additional experiments validated the robustness of the proposed framework under varying conditions. When applied to the third-day data from the public dataset (

Figure 7), where sensor placement and participant state inevitably differed from the second day, CLES-DA maintained an accuracy of

exceeded CLEN by 9.50 % (

; 95% CI: [6.58, 12.42]). The result demonstrates the stability of the approach against intra-subject variability across sessions.

Evaluation on the local dataset (

Figure 8), which involved different subjects and experimental settings, further demonstrated the generally of the proposed framework. After pre-training on the public dataset and adapting the model using approximately nine minutes of unlabeled sEMG data from the held-out local subject, CLES-DA achieved an accuracy of

, with stable precision (

), recall (

), and F1-score (

) as summarized in

Table 4. The cross-dataset consistency suggests that CLES-DA generalizes effectively across subjects and datasets.

3.4.3. Domain Adaptive Visualization

The effect of domain adaptation was further analyzed using t-SNE visualization of the learned feature space, as shown in

Figure 9. Before adaptation, samples from the source and target domains exhibited substantial overlap, with clusters corresponding to different control laws being indistinct. This distribution indicates that features extracted solely by CLEN were insufficient to separate domains, limiting cross-subject generalization.

After applying CLES-DA, the alignment between source and target domains improved markedly. Samples corresponding to the same control law, even when originating from different domains, converged into compact and well-separated clusters. This outcome illustrates that the adversarial training process effectively reduced inter-domain discrepancies while preserving task-relevant distinctions.

The visualization provides the support for the improvements in classification accuracy. The reduced overlap in feature space suggests that the proposed framework not only enhances predictive performance but also establishes a more interpretable and structured representation of EMG signals. The consistency across visualization and classification results reinforces the conclusion that CLES-DA is capable of addressing subject variability and ensuring reliable evaluation of exoskeleton control laws.

4. Discussion

This study introduced a contrastive and domain-adaptive framework for evaluating exoskeleton control laws using surface electromyography (sEMG). By encoding this preference directly as a binary label, the proposed framework focuses on the decision that matters for exoskeleton optimization selecting the better of two strategies, rather than on reconstructing a precise but noisy metabolic quantity.

To contextualize the regression baseline, the EEP model’s error level was compared with previously reported metabolic prediction studies. The comparison of consistency indicates that the EEP baseline used in our work is representative of current regression performance and that the variability observed across subjects is characteristic of metabolic regression rather than a limitation of our implementation. These observations further highlight the challenges of predicting absolute metabolic cost from wearable signals and motivate the transition toward a comparative classification formulation.

The transition from regression to classification was particularly effective. As shown in

Table 3, the prediction error of the EEP baseline is comparable to that reported in prior regression-based metabolic estimation study. However, regression-based EEP showed limited ability to generalize across individuals (58.5 ± 5.3% accuracy after conversion to pairwise comparisons), the CLEN classification model improved accuracy to 64.3 ± 3.7%. Incorporating domain adaptation further elevated performance to 77.6 ± 3.1%. These progressive gains demonstrate the advantage of focusing on relative differences between strategies rather than absolute metabolic values, which are more sensitive to subject-specific variability. Importantly, all evaluations were performed on the target domain, confirming that the observed improvements reflect generalization to unseen subjects and sessions.

Domain adaptation played a central role in the observed performance improvements. By aligning feature distributions between source and target domains, the Dual Adversarial Adaptive Optimization Strategy effectively mitigated inter-subject discrepancies. The robustness of this approach was further supported by the cross-day evaluation, where accuracy remained at 73.8 ± 3.4%, and by the local dataset, where comparable performance (73.3 ± 4.7%) was obtained despite differences in experimental setup. These results indicate that the proposed strategy provides a reliable mechanism for extending exoskeleton optimization beyond controlled laboratory environments.

The proposed method offers a practical and interpretable objective function for exoskeleton optimization. By directly ranking two control laws rather than predicting absolute energy expenditure, it delivers actionable feedback for tuning assistance parameters in rehabilitation and mobility enhancement. The improved generalization suggests that this framework could support adaptive exoskeleton control in diverse populations and environments.

Despite the promising results, several limitations remain. First, the current framework only considers binary comparisons of control laws, excluding cases where two strategies perform equally. Extending the labeling scheme to incorporate equality may further enhance the reliability of control law ranking. Second, the sample size remains limited, involving six subjects in the public dataset and four subjects in the local dataset. Larger-scale studies, particularly involving older adults or patients with gait impairments, are necessary to fully validate clinical applicability. Finally, although the framework effectively addresses inter-subject and cross-day variability, it has yet to be evaluated in free-living conditions where additional factors such as fatigue and terrain variability may influence signal quality.

Although the present study evaluates CLES-DA entirely in offline settings, the proposed framework shows clear potential for integration into step-level exoskeleton optimization. The forward inference is computationally lightweight, requiring only 1–2 ms to evaluate a pair of sEMG gait cycles on a standard GPU, which is sufficient for low-frequency parameter adjustment loops commonly used in human-in-the-loop optimization. For new users, domain adaptation can be performed with a modest amount of unlabeled data (approximately 9 min of walking), followed by an offline adaptation procedure. These characteristics suggest that the method can be feasibly incorporated into practical personalization pipelines.

Overall, the findings highlight the potential of contrastive and domain-adaptive evaluation strategies for exoskeleton optimization. By demonstrating consistent improvements under target-domain conditions, the study provides evidence that sEMG-based comparative evaluation can serve as a practical and generalizable objective function. This capability is essential for advancing exoskeleton assistance from controlled laboratory research toward real-world rehabilitation and mobility applications.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed a domain adaptive evaluation framework that reformulates energy expenditure prediction as a contrastive classification task and integrates a dual adversarial optimization strategy. The proposed method consistently outperformed regression-based approaches under cross-subject and cross-day conditions, achieving accuracies of 77.6 ± 3.1% on the public dataset and 73.3 ± 4.7% on the local dataset.

By mitigating inter-subject variability and emphasizing relative strategy comparison, the framework offers a robust and interpretable objective function for exoskeleton optimization. Future work will extend this approach to patient populations and real-world environments, advancing toward adaptive, personalized, and clinically applicable exoskeleton assistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.D. and Y.L.; methodology, Z.D. and Y.L.; software, P.J. and Y.L.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Z.D. and Y.L.; resources, Y.L. and C.Y. (Chifu Yang); data curation, C.Y. (Chunzhi Yi); writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.D.; visualization, P.J.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Z.D. and Y.L.; funding acquisition, Z.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Heilongjiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LH2024F004).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Chinese Ethics Committee of Registering Clinical Trials (ChiECRCT20200319).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 5.1 for the purposes of language polishing, grammar. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fettrow, T.; Hupfeld, K.; Hass, C.; Pasternak, O.; Seidler, R. Neural correlates of gait adaptation in younger and older adults. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, M.D.; Psaltos, D.; Zhang, H.; Adamusiak, T.; Calicchio, M.; Kelekar, A.; Messere, A.; Van Dijk, K.R.; Ramos, V.; Demanuele, C.; et al. Age and environment-related differences in gait in healthy adults using wearables. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, C.; Packer, E.; Polhemus, A.; MacLean, M.K.; Bailey, H.; Kluge, F.; Gaßner, H.; Rochester, L.; Del Din, S.; Yarnall, A.J. A systematic review of real-world gait-related digital mobility outcomes in Parkinson’s disease. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, J.; Yu, S.; Dominguez Silva, I.; Wang, T.; Rouse, E.; Zhou, B.; Yuk, H.; et al. Experiment-free exoskeleton assistance via learning in simulation. Nature 2024, 630, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siviy, C.; Baker, L.M.; Quinlivan, B.T.; Porciuncula, F.; Swaminathan, K.; Awad, L.N.; Walsh, C.J. Opportunities and challenges in the development of exoskeletons for locomotor assistance. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 456–472. [Google Scholar]

- Divekar, N.V.; Thomas, G.C.; Yerva, A.R.; Frame, H.B.; Gregg, R.D. A versatile knee exoskeleton mitigates quadriceps fatigue in lifting, lowering, and carrying tasks. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadr8282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, S.; Tonin, L.; Sieghartsleitner, S.; Ortner, R.; Guger, C.; Lennon, O.; Coyle, D.; Menegatti, E.; Del Felice, A. Effect of lower limb exoskeleton on the modulation of neural activity and gait classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 2988–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Quinlivan, B.T.; Deprey, L.A.; Arumukhom Revi, D.; Eckert-Erdheim, A.; Murphy, P.; Orzel, D.; Walsh, C.J. Reducing the energy cost of walking with low assistance levels through optimized hip flexion assistance from a soft exosuit. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybart, R.; Villancio-Wolter, K.S.; Ferris, D.P. Metabolic cost of walking with electromechanical ankle exoskeletons under proportional myoelectric control on a treadmill and outdoors. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fiers, P.; Witte, K.A.; Jackson, R.W.; Poggensee, K.L.; Atkeson, C.G.; Collins, S.H. Human-in-the-loop optimization of exoskeleton assistance during walking. Science 2017, 356, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Kim, M.; Kuindersma, S.; Walsh, C.J. Human-in-the-loop optimization of hip assistance with a soft exosuit during walking. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3, eaar5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, J. Selection of muscle-activity-based cost function in human-in-the-loop optimization of multi-gait ankle exoskeleton assistance. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2021, 29, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.; Kochenderfer, M.J.; Delp, S.L.; Collins, S.H. Personalizing exoskeleton assistance while walking in the real world. Nature 2022, 610, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.A.; Voß, M.; Dillen, A.; Tassignon, B.; Flynn, L.; Geeroms, J. Human-in-the-loop optimization of wearable robotic devices to improve human–robot interaction: A systematic review. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 53, 7483–7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; ALDuhishy, A.; González-Haro, C. Validation of the cosmed K4b2 portable metabolic system during running outdoors. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Figueiredo, J.; Fonseca, P.; Cerqueira, J.J.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Santos, C.P. Deep learning-based energy expenditure estimation in assisted and non-assisted gait using inertial, EMG, and heart rate wearable sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 7913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, R.E.; Vos, P.; Wedge, R.D. Electromyography as a surrogate for estimating metabolic energy expenditure during locomotion. Med. Eng. Phys. 2022, 109, 103899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingraham, K.A.; Ferris, D.P.; Remy, C.D. Evaluating physiological signal salience for estimating metabolic energy cost from wearable sensors. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 126, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingraham, K.A.; Rouse, E.J.; Remy, C.D. Accelerating the estimation of metabolic cost using signal derivatives: Implications for optimization and evaluation of wearable robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2019, 27, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, N.; Farringdon, J.; Andre, D.; Stivoric, J.I. Machine learning and sensor fusion for estimating continuous energy expenditure. AI Mag. 2012, 33, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.; Troutman, R.; Kochenderfer, M.J.; Collins, S.H.; Delp, S.L. Rapid energy expenditure estimation for ankle assisted and inclined loaded walking. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Romano, C.; Pedram, M.; Nolan, B.; Morelli, W.A.; Alshurafa, N. Developing and comparing a new BMI inclusive energy expenditure algorithm on wrist-worn wearables. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kantharaju, P.; Yi, H.; Jacobson, M.; Jeong, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Matthews, J.; Zavanelli, N.; Kim, H.; et al. Soft wearable flexible bioelectronics integrated with an ankle-foot exoskeleton for estimation of metabolic costs and physical effort. npj Flex. Electron. 2023, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.F.; McGreavy, C.; Christou, A.; Vijayakumar, S. Human-in-the-loop optimization of exoskeleton assistance via online simulation of metabolic cost. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 1410–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Roh, J.h.; Kim, S. Siamese network-based user-independent model for surface electromyogram biometric authentication. ETRI J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinger, J.C.; Donelan, J.M. Estimating instantaneous energetic cost during non-steady-state gait. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 117, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganin, Y.; Ustinova, E.; Ajakan, H.; Germain, P.; Larochelle, H.; Laviolette, F.; March, M.; Lempitsky, V. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2016, 17, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, K.; Watanabe, K.; Ushiku, Y.; Harada, T. Maximum classifier discrepancy for unsupervised domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conferenceon Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3723–3732. [Google Scholar]

- Ganin, Y.; Lempitsky, V. Unsupervised domain adaptation by backpropagation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 1180–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Poggensee, K.L.; Collins, S.H. Continued Optimization #1. Stanford Digital Repository. Available online: https://purl.stanford.edu/jj710vy7867 (accessed on 15 November 2023).

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed method. A method that evaluates exoskeleton control laws based on sEMG signals from each gait cycle of the subject. The subject experiences two exoskeleton control laws: control law A (blue) and control law B (red). Then, the collected sEMG signals at each gait cycle are downsampled and used as inputs for the model. Through forward propagation, the network generates an output indicating which control law is superior. This process iterates until the model reaches a predefined termination condition.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed method. A method that evaluates exoskeleton control laws based on sEMG signals from each gait cycle of the subject. The subject experiences two exoskeleton control laws: control law A (blue) and control law B (red). Then, the collected sEMG signals at each gait cycle are downsampled and used as inputs for the model. Through forward propagation, the network generates an output indicating which control law is superior. This process iterates until the model reaches a predefined termination condition.

Figure 2.

Structure and workflow of the proposed CLES-DA. Using a labeled source domain , an unlabeled target domain , and a domain label .

Figure 2.

Structure and workflow of the proposed CLES-DA. Using a labeled source domain , an unlabeled target domain , and a domain label .

Figure 3.

Architecture of the feature generator (G), main classifier (C1), auxiliary classifier (C2), and domain discriminator (D).The feature generator extracts representations from sEMG images, which are then classified by C1 and C2. The domain discriminator receives the same features through a gradient-reversal layer during training to encourage domain-invariant feature learning.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the feature generator (G), main classifier (C1), auxiliary classifier (C2), and domain discriminator (D).The feature generator extracts representations from sEMG images, which are then classified by C1 and C2. The domain discriminator receives the same features through a gradient-reversal layer during training to encourage domain-invariant feature learning.

Figure 4.

Experimental setup: (a) Schematic of experimental setup, (b) Photograph of ankle exoskeleton, and (c) illustration of control laws.

Figure 4.

Experimental setup: (a) Schematic of experimental setup, (b) Photograph of ankle exoskeleton, and (c) illustration of control laws.

Figure 5.

Representative examples of model estimation versus measured energy expenditure from the public dataset.

Figure 5.

Representative examples of model estimation versus measured energy expenditure from the public dataset.

Figure 6.

Performance comparison of CLES-DA, EEP, and CLEN on the Day 2 data of the public dataset.

Figure 6.

Performance comparison of CLES-DA, EEP, and CLEN on the Day 2 data of the public dataset.

Figure 7.

Performance of CLES-DA on Day 3 data of the public dataset.

Figure 7.

Performance of CLES-DA on Day 3 data of the public dataset.

Figure 8.

Performance of CLES-DA on the locally collected dataset across subjects.

Figure 8.

Performance of CLES-DA on the locally collected dataset across subjects.

Figure 9.

The t-SNE visualization of sample distributions from a representative subject in both the source domain SD (a,c) and the target domain TD (b,d), before (a,b) and after (c,d) the CLES-DA.

Figure 9.

The t-SNE visualization of sample distributions from a representative subject in both the source domain SD (a,c) and the target domain TD (b,d), before (a,b) and after (c,d) the CLES-DA.

Table 1.

Parameters of control laws used in the local dataset for exoskeleton assistance experiments.

Table 1.

Parameters of control laws used in the local dataset for exoskeleton assistance experiments.

| Rise Time (%) | Peak Time (%) | Peak Force (N) | Fall Time (%) |

|---|

| 20 | 46, 49, 52 | 50, 100, 150 | 10 |

Table 2.

Energy expenditure prediction errors (percentage error and RMSE) per gait cycle across subjects in the public dataset.

Table 2.

Energy expenditure prediction errors (percentage error and RMSE) per gait cycle across subjects in the public dataset.

| Metric | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | Mean (Ours) | [21] | [18] | [16] |

|---|

| Error (%) | 10.1 | 6.1 | 9.3 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 13.8 | 9.7 | 8.1 | - | - |

| RMSE * () | 0.73 | 0.4 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.6 | 0.91 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 1.0 | 0.44 |

Table 3.

Per-subject accuracy (%) of EEP, CLEN, and CLES-DA on the public sEMG dataset under the leave-one-subject-out (LOO) evaluation protocol.

Table 3.

Per-subject accuracy (%) of EEP, CLEN, and CLES-DA on the public sEMG dataset under the leave-one-subject-out (LOO) evaluation protocol.

| Subject | EEP | CLEN | CLES-DA | Day 3 (CLES-DA) |

|---|

| S1 | 54.7 | 60.6 | 72.5 | 71.3 |

| S2 | 65.2 | 66.1 | 81.3 | 76.8 |

| S3 | 61.3 | 67 | 81.2 | 75.6 |

| S4 | 62.6 | 69.8 | 77.6 | 78.2 |

| S5 | 57.9 | 63.1 | 75.3 | 68.3 |

| S6 | 49.2 | 59.4 | 77.7 | 72.8 |

| Accuracy (Mean ± SD) | | | | |

Table 4.

The performance metrics (mean ± SD) of the evaluated methods.Metrics for EEP, CLEN, and CLES-DA are computed on the public dataset; CLES-DA (Day 3) denotes cross-day evaluation on the public dataset; CLES-DA (Local) denotes evaluation after adaptation on the local dataset.

Table 4.

The performance metrics (mean ± SD) of the evaluated methods.Metrics for EEP, CLEN, and CLES-DA are computed on the public dataset; CLES-DA (Day 3) denotes cross-day evaluation on the public dataset; CLES-DA (Local) denotes evaluation after adaptation on the local dataset.

| Metric | EEP | CLEN | CLES-DA | CLES-DA (Day 3) | CLES-DA (Local) |

|---|

| Precision | | | | | |

| Recall | | | | | |

| F1-score | | | | | |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).