Matrix-Guided Safe Motion Planning for Smart Parking Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

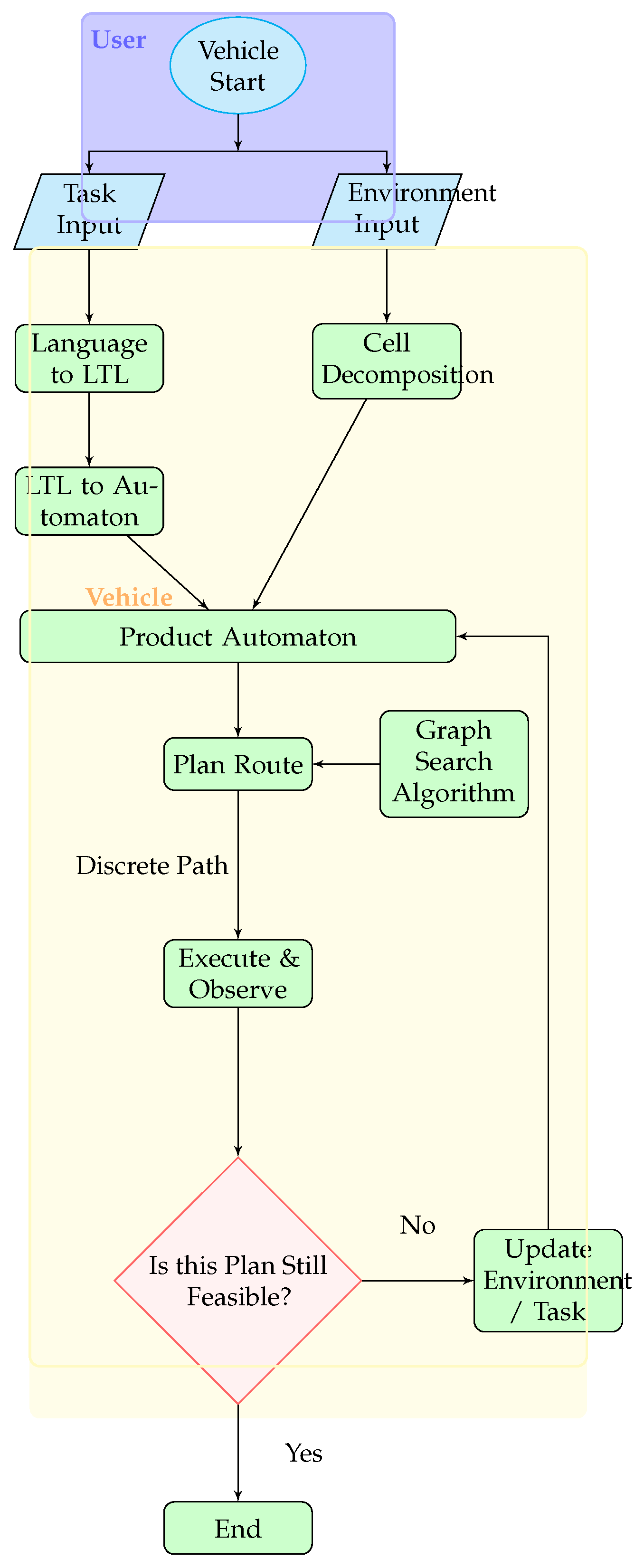

1.2. Contributions

- Modular LTL-Based Planning Framework:We propose a modular SPTL framework for LTL-based applications that enables seamless integration with automated test environments. The framework can be tested and validated in a high-fidelity simulation environment, supporting dynamic updates, traffic rules, and plug-and-play agent orchestration.

- Matrix-Based Abstraction for Automaton Composition:We present a matrix-centric product automaton composition that replaces conventional automata-theoretic operations with algebraic formulations. This allows for scalable and efficient computation using structured matrix operations rather than explicit state-space exploration.

- Conditional Block Product Operator:We introduce a novel binary operator, termed the Conditional Block Product, enabling the structured construction of “product matrices” conditioned on logical formulas—facilitating more compact and logically expressive representations.

- Agility of the SPTL:The proposed framework supports on-the-fly replanning in response to dynamic task updates or environmental changes, enabling adaptive and reactive decision-making under evolving mission specifications.

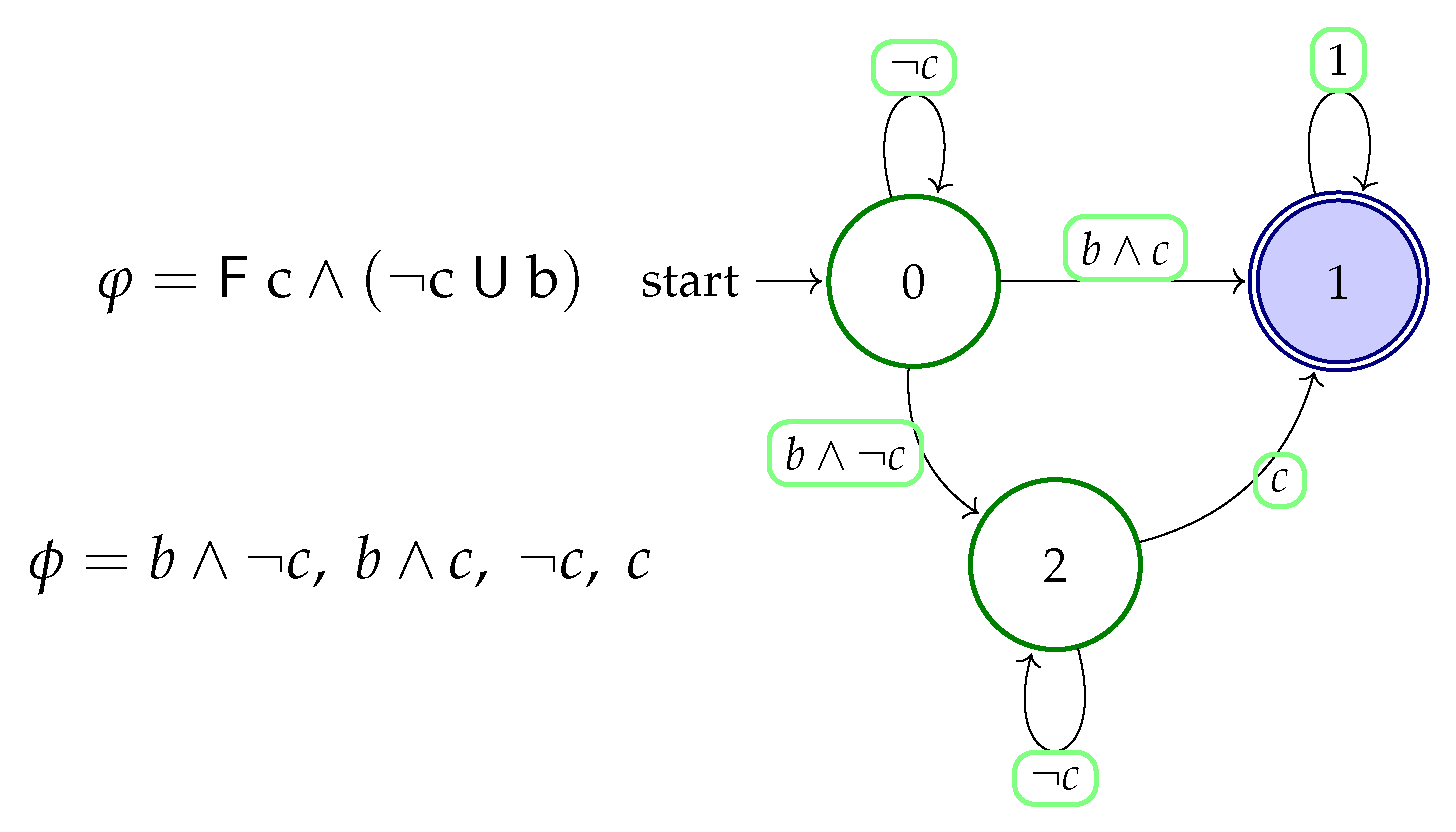

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Automaton

- is a finite set containing the states.

- is a finite set called the alphabet or the action/input set.

- is the transition relation: , which dictates how one states move to another upon applying an input.

- is the start state, where .

- is the set of final states / accepted states, .

- .

- = a finite set called the alphabet/action/input.

- .

- .

- iff and .

2.2. Atomic Proposition, Labeling Function, and Linear Temporal Logic (LTL)

- true is a logical constant representing a condition that is always true,

- π represents an atomic proposition,

- ¬, ∧ are classical logic operators (negation and conjunction, respectively),

- (next), (eventually), (globally) are temporal operators,

- (until) is a binary temporal operator.

- is always certained.

- iff it is not the case that .

- iff and .

- iff .

- iff there exists a such that .

- iff for all , .

- iff there exists a such that and for all , .

- Safety properties: Something bad never happens.

- Liveness properties: Something good eventually happens.

- Fairness conditions: If some conditions are repeatedly met, then something good eventually happens.

3. Problem Formulation

4. Methodology

4.1. Automaton to Matrix: A Computationally Efficient Environment and Task Representation

- If there exists a transition , where is a logical formula over atomic propositions (e.g., , ), then . This includes conditional self-loops when .

- If there exists an unconditional self-loop, i.e., , then . This indicates a transition that is always enabled.

- If no transition from i to j is defined in the task automaton, then .

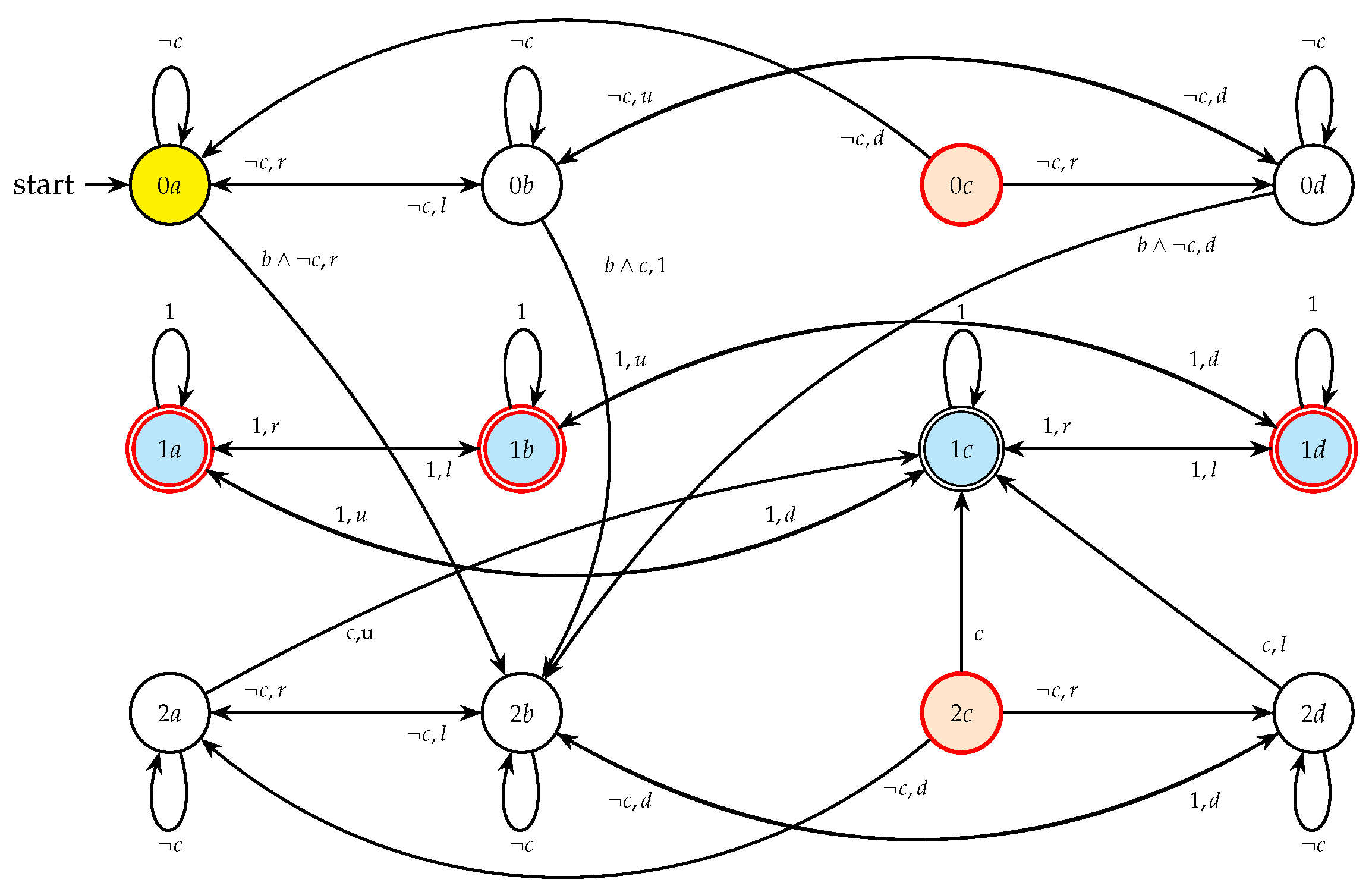

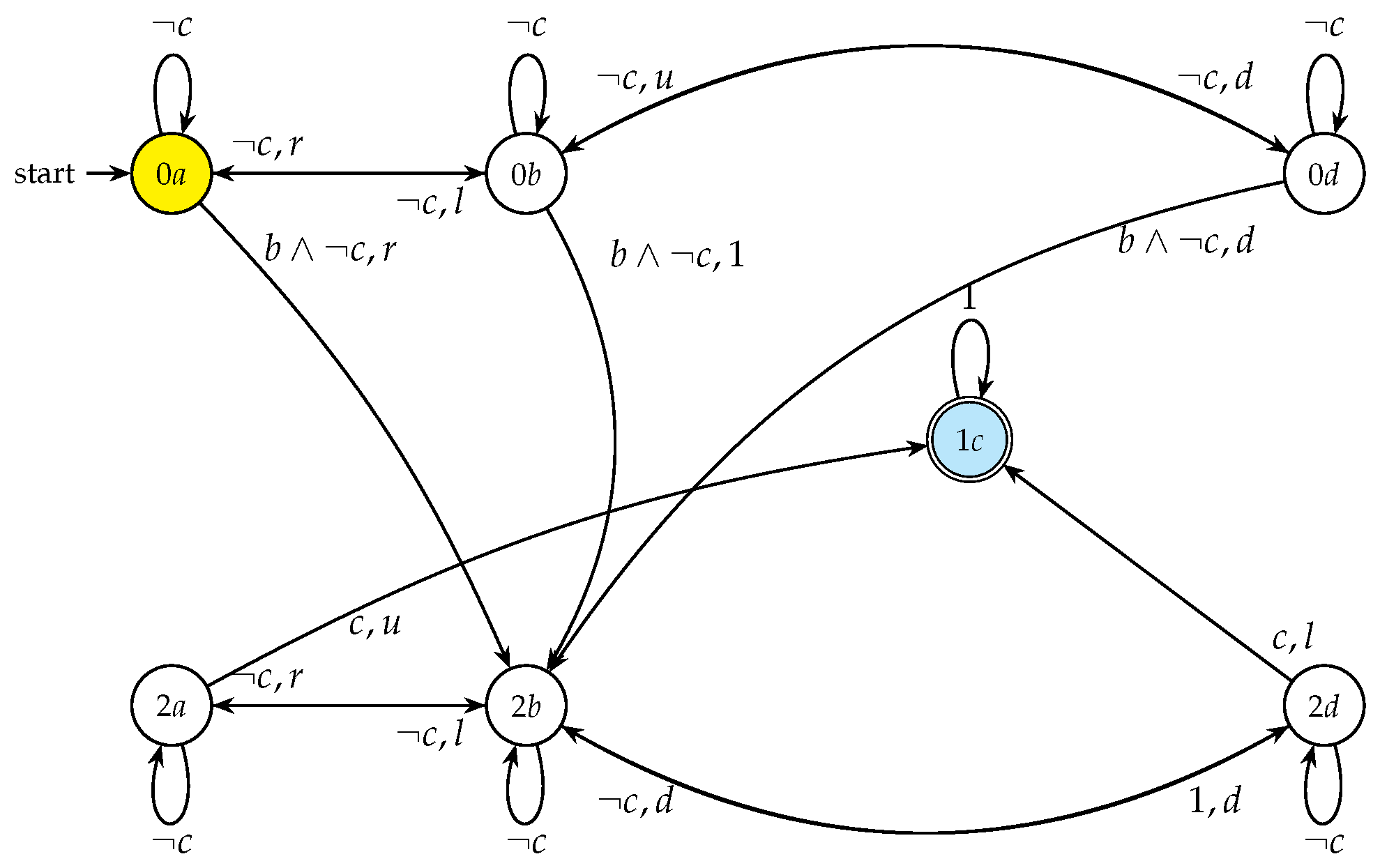

4.2. Product Automaton Matrix: Matrix Fusion for Integrated Planning

4.2.1. Boolean Operations on Atomic Matrices (For Formulas)

- Conjunction (∧) and Disjunction (∨): These operations are performed as direct element-wise AND and OR on the operand matrices. For instance, . Because the base matrices are already filtered by the environment connectivity, the results of these operations are inherently valid paths.

- Negation (¬): The negation of a formula, , represents all valid environment transitions where the condition is not met. This is calculated by taking the element-wise complement of (which marks transitions where is false) and then performing an element-wise AND with the environment connectivity matrix . This final AND operation ensures that the resulting matrix only contains transitions that are physically possible in the environment.

4.2.2. Building Product Automaton Matrix

- such that , and

- .

4.2.3. Formalizing the Product via Conditional Block Operator

- If , the corresponding block is the zero matrix.

- If , the block is assigned the matrix .

4.3. Pruning of Product Automaton Matrix

4.4. Path Planning in Product Automaton Matrix

| Algorithm 1: Path Planning with LTL Constraint | |

| |

| //Using available tool SPOT // Equation (6) //Remark 2 // (initial state of ) |

5. Results & Discussions

- Experiment 1: Shortest-path planning with a change in task requirements.

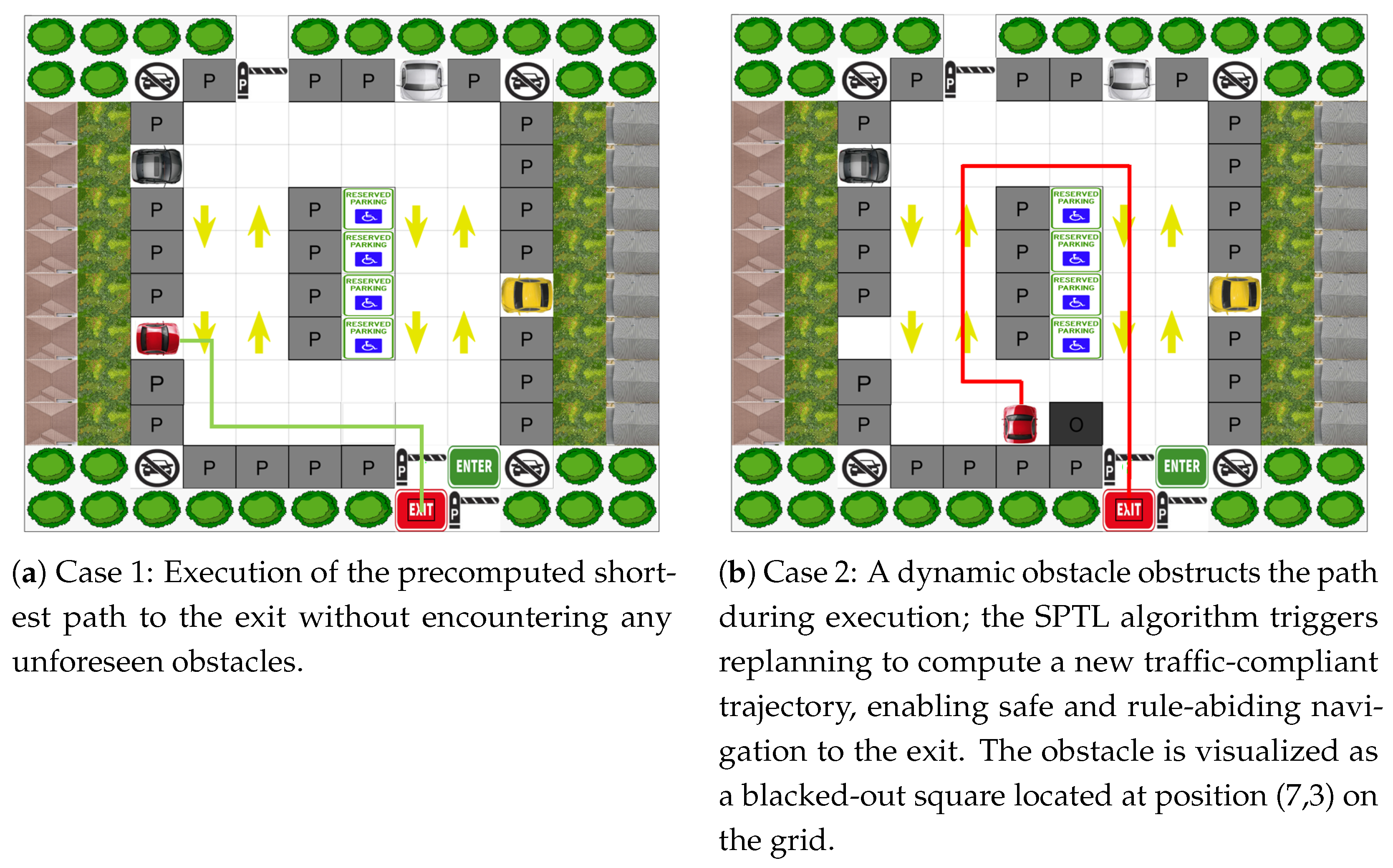

- Experiment 2: Introduction of one-way traffic rules and a dynamic obstacle, testing rule enforcement and replanning.

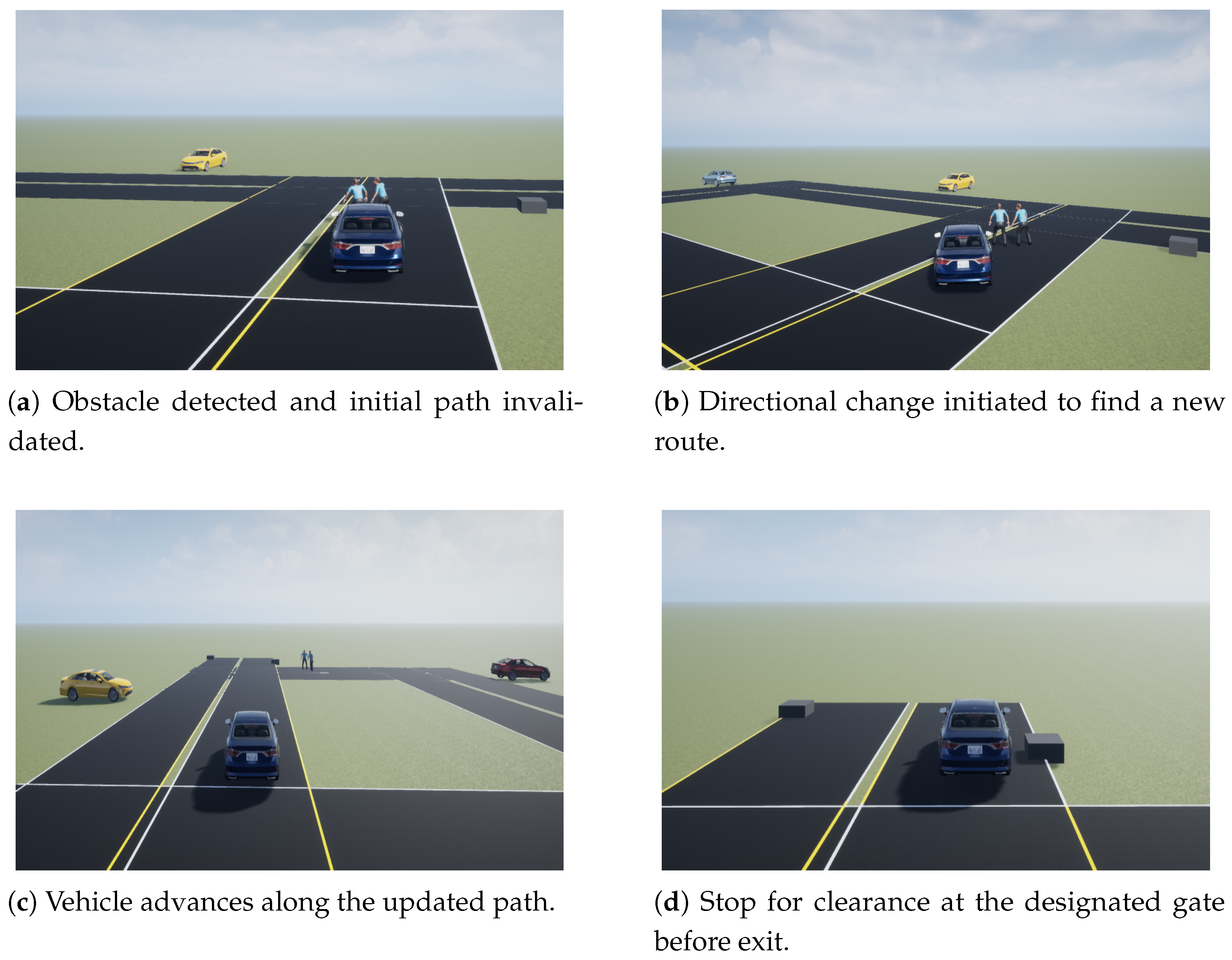

- Experiment 3: Dynamic goal change mid-mission due to a road blockage, evaluating the agility of the planner.

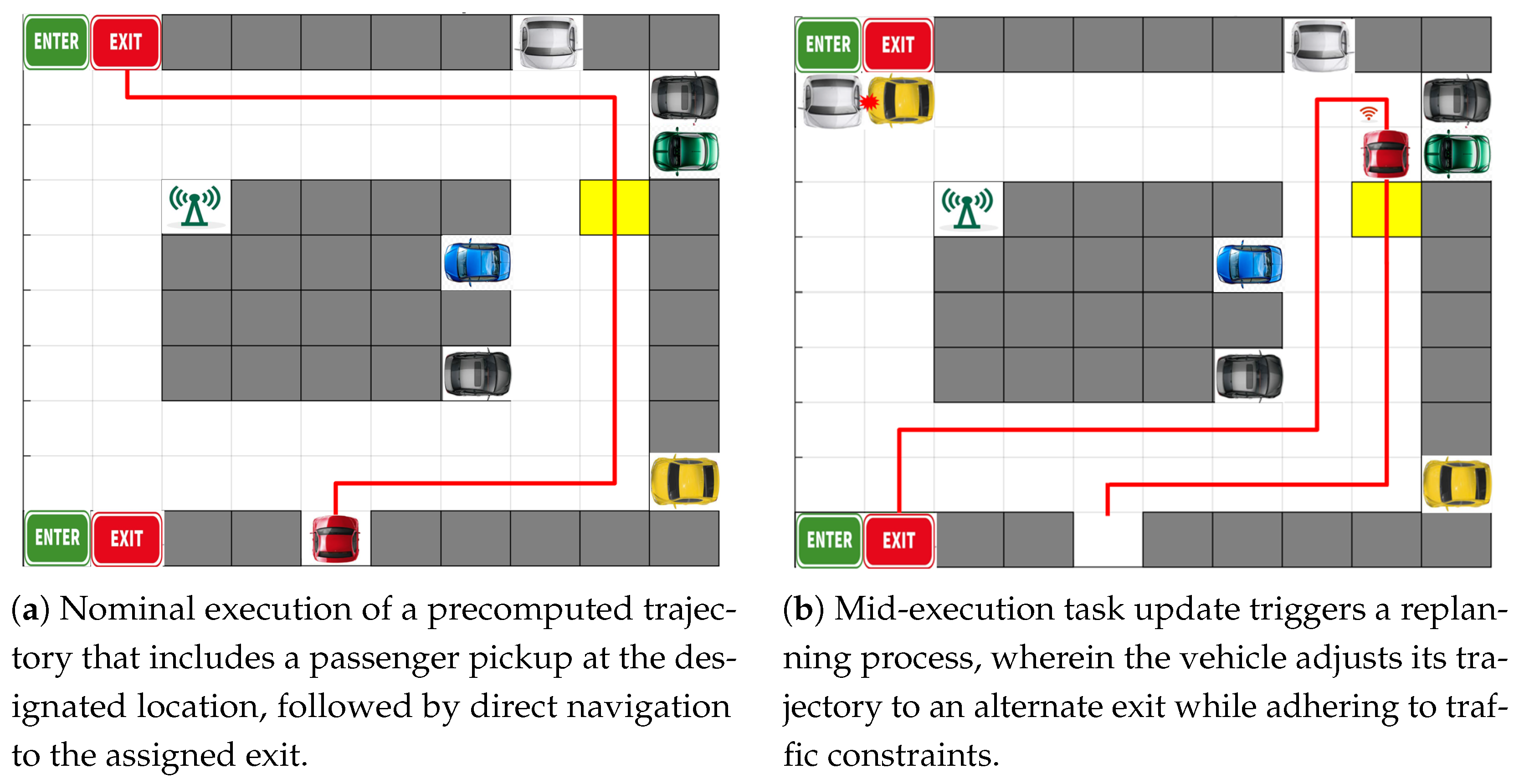

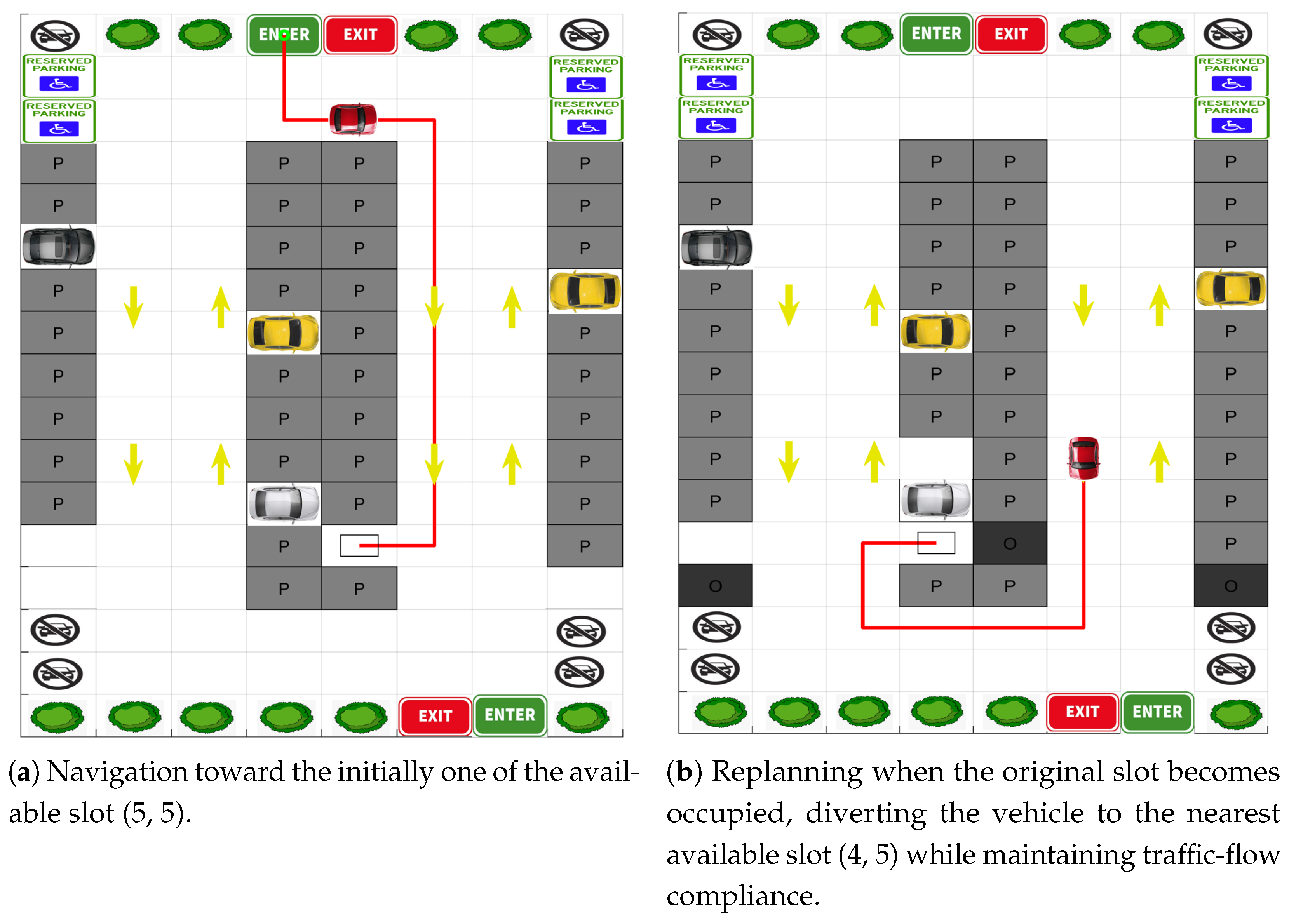

- Experiment 4: Smart parking with real-time slot updates and dynamic goal reassignment.

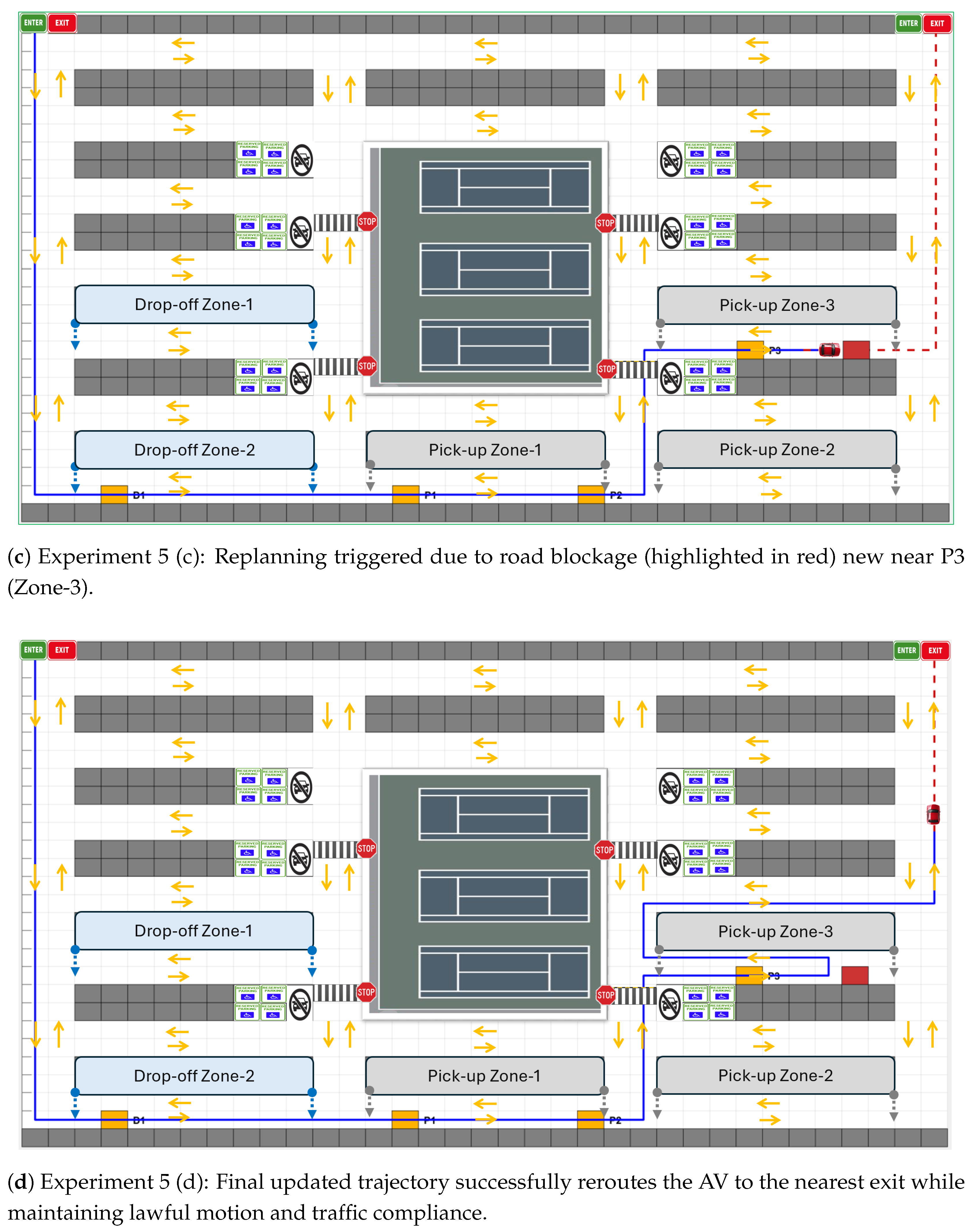

- Experiment 5: Multi-stage autonomous mission integrating drop-off, pick-up, task cancellation, and obstacle avoidance in a large-scale parking environment.

- Experiment 6: A computational benchmark comparing the Product Automaton generation time of the proposed matrix-based method against a traditional iterative, automata-theoretic approach during a dynamic task change.

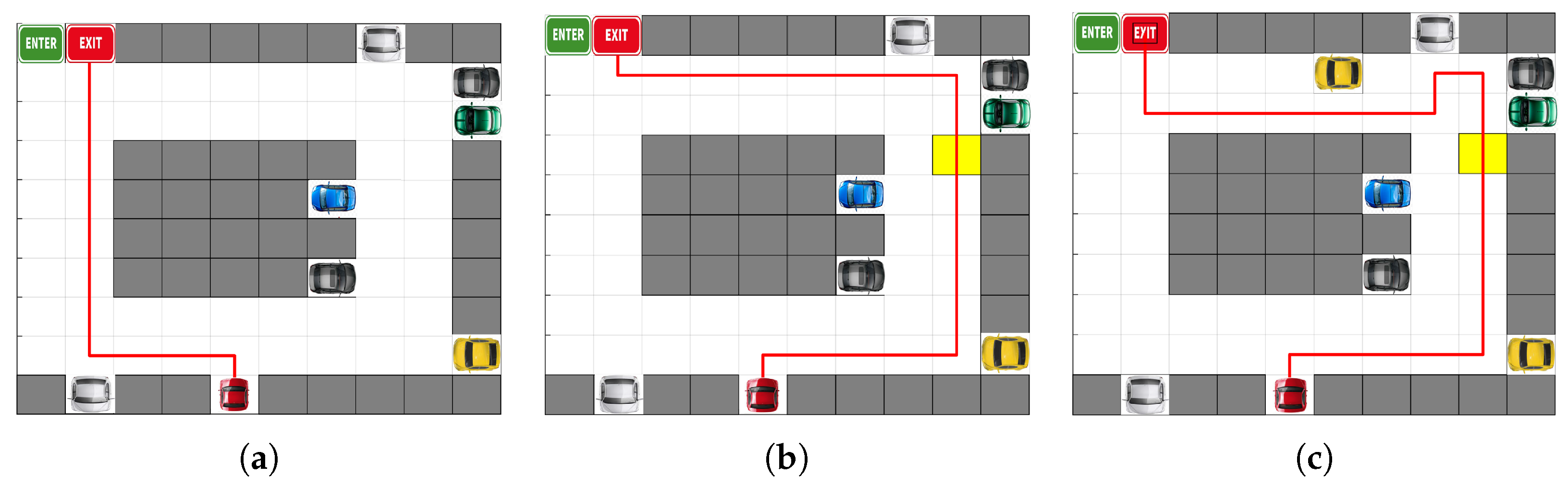

5.1. Experiment 1: Shortest-Path Planning with Task Modifications

5.2. Experiment 2: Traffic Rules and Dynamic Obstacle Handling

5.3. Experiment 3: Dynamic Goal Change and Replanning

5.4. Experiment 4: Smart Parking with Dynamic Goal Reassignment

5.5. Experiment 5: Multi-Stage Task Execution with Dynamic Re-Planning

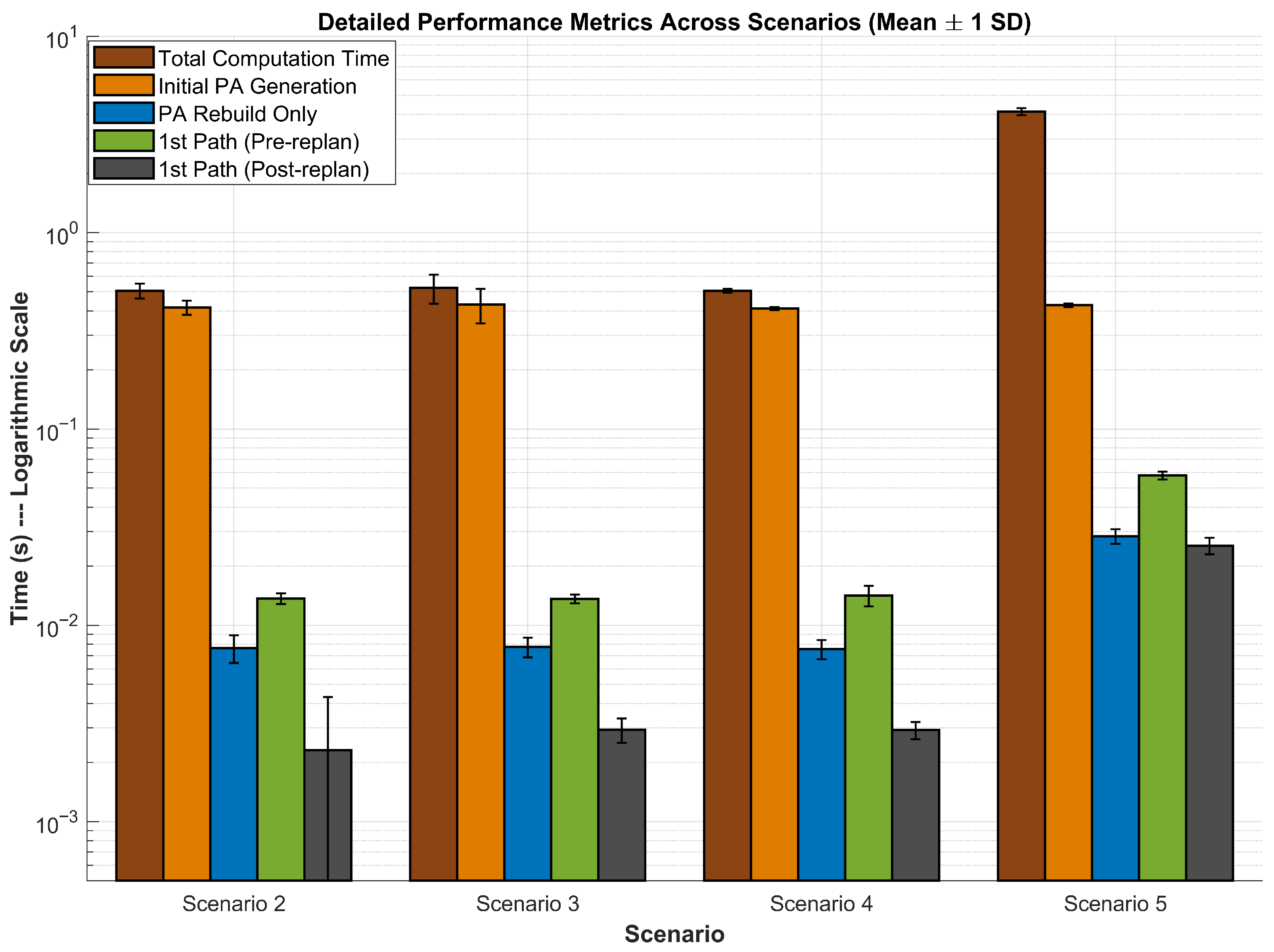

5.6. Quantitative Comparison and Performance Trends

5.7. Experiment 6: Comparative Benchmark of Replanning Computation

- Our Proposed Matrix-Based Method: This method first computes the atomic proposition matrices (e.g., , ) once. It then constructs the final Product Automaton matrix () using Boolean operations. When a new task () is given, it reuses the atomic matrices and only re-runs the Boolean operations to build .

- Traditional Automata-Based Method: This method iterates through every environment state and task state to build the product automaton “from scratch” for . When the task changes to , it must discard its previous work and re-run the entire “from-scratch” iterative process.

- Task 1: “”

- Task 2: “”

- Initial Computation Speed: Our matrix-based method demonstrates a significant performance advantage, completing the initial build in s compared to s for the traditional method. This represents a 1.93× speedup, attributable to the efficient vectorized matrix operations utilized in our framework.

- Replanning Efficiency (Key Contribution): For the replanning phase, our method completes Task 2 in s, whereas the traditional method requires s. This reflects a 2.01× speedup, highlighting the matrix-based method’s architectural efficiency for dynamic replanning. Notably, our approach avoids full reconstruction of the product automaton during replanning, in contrast to the traditional method which re-executes the entire computation pipeline. Optionally, this also explains why our Task 2 is faster than even our Task 1 (by ∼1.09×), due to the reuse of atomic propositions instead of recomputation.

- Total Computation Time: When combining both tasks, the matrix-based method completes planning in s on average—over 2.94× faster than the traditional method’s s. This underscores the method’s suitability for time-critical applications requiring both initial and reactive planning responsiveness.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Construction and Validation of the Product Automaton

- States: .

- Initial state: .

- Accepting states: .

References

- Miao, X.; Duan, M. A Study on Parking Problems and Countermeasures of Urban Central Commercial District. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical and Information Technologies for Rail Transportation-Volume II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 601–608. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Liang, H.; Mei, T.; Zhu, H. Research on self-parking path planning algorithms. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety, Beijing, China, 10–12 July 2011; pp. 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, G.; Pishue, B. The Impact of Parking Pain in the US, UK and Germany. Available online: https://www2.inrix.com/research-parking-2017 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Shoup, D.C. Cruising for parking. Transp. Policy 2006, 13, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transline. Parking Lot Accident Statistics–Making Parking Lots Safer. 2023. Available online: https://translineinc.com/parking-lot-accident-statistics/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts 2020: A Compilation of Motor Vehicle Crash Data; Technical Report; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GITNUX. Parking Lot Accident Statistics [Fresh Research]. 2024. Available online: https://gitnux.org/parking-lot-accident-statistics/#content (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Non-Traffic Surveillance (NTS). 2024. Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/crash-data-systems/non-traffic-surveillance (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- National Safety Council. Pedestrians: Data Details. 2024. Available online: https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/motor-vehicle/road-users/pedestrians/data-details/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Nations, U. 68% of the World Population Projected to Live in Urban Areas by 2050, Says UN. 2023. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Rupareliya, P.K. IOT in Smart Parking System—Problems, Solutions, Applications. 2022. Available online: https://www.intuz.com/blog/iot-in-smart-parking-management-benefits-challenges (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Mulloy, R. Solving Parking Challenges with Smart Solutions and Innovations. 2023. Available online: https://operationscommander.com/blog/parking-management-challenges/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Daxwanger, W.; Schmidt, G. Skill-based visual parking control using neural and fuzzy networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics. Intelligent Systems for the 21st Century, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–25 October 1995; Volume 2, pp. 1659–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorinevsky, D.; Kapitanovsky, A.; Goldenberg, A. Neural network architecture for trajectory generation and control of automated car parking. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 1996, 4, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Widrow, B. Neural networks for self-learning control systems. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 1990, 10, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, B.; Yih, S. Learning to control: A heterogeneous approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Control, Albany, NY, USA, 25–26 September 1989; pp. 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugeno, M.; Murakami, K. Fuzzy parking control of model car. In Proceedings of the 23rd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 1984; pp. 902–903. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.H.S.; Chang, S.J.; Chen, Y.X. Implementation of human-like driving skills by autonomous fuzzy behavior control on an FPGA-based car-like mobile robot. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2003, 50, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.H.S.; Chang, S.J. Autonomous Fuzzy Parking Control of a Car-Like Mobile Robot. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 2003, 33, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, D.; Probert, P. New techniques for genetic development of a class of fuzzy controllers. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 1998, 28, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Collins, E.G. Robust automatic parallel parking in tight spaces via fuzzy logic. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2005, 51, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.J. Multiple Designs of Fuzzy Controllers for Car Parking Using Evolutionary Algorithm. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics, Harbin, China, 5–9 May 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, Y.W.; Oh, S.Y.; Kim, S. Robust Automatic Parking without Odometry Using Enhanced Fuzzy Logic Controller. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–21 July 2006; pp. 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgov, D.; Thrun, S.; Montemerlo, M.; Diebel, J. Practical Search Techniques in Path Planning for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling, Sydney, Australia, 14–18 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Montemerlo, M.; Becker, J.; Bhat, S.; Dahlkamp, H.; Dolgov, D.; Ettinger, S.; Haehnel, D.; Hilden, T.; Hoffmann, G.; Huhnke, B.; et al. Junior: The Stanford Entry in the Urban Challenge. J. Field Robot. 2008, 25, 569–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Chen, X.; Hu, M.; Chen, L.; Fan, J. A novel path planning methodology for automated valet parking based on directional graph search and geometry curve. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 132, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi, S.; Nguyen, D.V.; Kapsalas, P.; Kuhnert, K.D. Implementing Voronoi-based Guided Hybrid A* in Global Path Planning for Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 3845–3852. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, W.; Li, B.; Zhong, X. Autonomous Parking Trajectory Planning With Tiny Passages: A Combination of Multistage Hybrid A-Star Algorithm and Numerical Optimal Control. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 102801–102810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Zhang, S.; Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Zheng, N. Curvature Continuous Path Planning with Reverse Searching for Efficient and Precise Autonomous Parking. In Proceedings of the IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Macau, China, 8–12 October 2022; pp. 2798–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liniger, A.; Sakai, A.; Borrelli, F. Autonomous Parking Using Optimization-Based Collision Avoidance. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 17–19 December 2018; pp. 4327–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Yang, X. Research on Automatic Vertical Parking Path-Planning Algorithms for Narrow Parking Spaces. Electronics 2023, 12, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposto, F.; Goos, J.; Teerhuis, A.; Alirezaei, M. Hybrid path planning for non-holonomic autonomous vehicles: An experimental evaluation. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE International Conference on Models and Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems, Naples, Italy, 26–28 June 2017; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, D.C.; Kress-Gazit, H.; Choset, H.; Rizzi, A.A.; Pappas, G.J. Valet parking without a valet. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2007; pp. 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniotti, M.; Mishra, B. Discrete event models+temporal logic=supervisory controller: Automatic synthesis of locomotion controllers. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Nagoya, Japan, 21–27 May 1995; Volume 2, pp. 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainekos, G.; Kress-Gazit, H.; Pappas, G. Temporal Logic Motion Planning for Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005; pp. 2020–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belta, C.; Isler, V.; Pappas, G. Discrete abstractions for robot motion planning and control in polygonal environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2005, 21, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpiromsarn, T.; Topcu, U.; Murray, R.M. Receding horizon temporal logic planning for dynamical systems. In Proceedings of the 48h IEEE Conference on Decision and Control Held Jointly with 28th Chinese Control Conference, Shanghai, China, 16–18 December 2009; pp. 5997–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.J.; Gao, Y.; Xie, L.; Johansson, K.H. Ensuring safety for vehicle parking tasks using Hamilton-Jacobi reachability analysis. In Proceedings of the 59th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 14–18 December 2020; pp. 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badithela, A.; Graebener, J.; Murray, R.M. Minimally Constrained Testing for Autonomy with Temporal Logic Specifications. In Proceedings of the RSS Workshop on Envisioning an Infrastructure for Multi-Robot and Collaborative Autonomy Testing and Evaluation, New York, NY, USA, 26–27 June 2022; Robotics: Science and Systems Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Seo, S.W. A Learning-Based Framework for Handling Dilemmas in Urban Automated Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 1436–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Abbeel, P.; Dolgov, D.; Ng, A.Y.; Thrun, S. Apprenticeship Learning for Motion Planning with Application to Parking Lot Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 1083–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Aatif, M.; Baig, M.Z.; Adeel, U.; Rashid, A. Path Planning with Adaptive Autonomy Based on an Improved A* Algorithm and Dynamic Programming for Mobile Robots. Information 2025, 16, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Lin, C.L.; Shiu, B.M. Autonomous Vehicle Parking Using Hybrid Artificial Intelligent Approach. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2009, 56, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakrani, N.; Joshi, M. An Intelligent Fuzzy based Hybrid Approach for Parallel Parking in Dynamic Environment. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 133, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.G.; Kosko, B. Comparison of fuzzy and neural truck backer-upper control systems. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, San Diego, CA, USA, 17–21 June 1990; Volume 3, pp. 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunobu, S.; Murai, Y. Parking control based on predictive fuzzy control. In Proceedings of the IEEE 3rd International Fuzzy Systems Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–29 June 1994; Volume 2, pp. 1338–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, M.; Kim, T.Q. Cell mapping based fuzzy control of car parking. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.98CH36146), Leuven, Belgium, 20 May 1998; Volume 3, pp. 2494–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bravo, F.; Cuesta, F.; Ollero, A. Parallel and diagonal parking in nonholonomic autonomous vehicles. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2001, 14, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.H.S.; Yeh, Y.C.; Wu, J.D.; Hsiao, M.Y.; Chen, C.Y. Multifunctional Intelligent Autonomous Parking Controllers for Carlike Mobile Robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 57, 1687–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Yang, T.; Huang, J.; Jin, W.; Zhang, W.; Jia, Y.; Wan, K.; Xiao, G.; Yang, D.; Zhong, Z. Improved Hybrid A-star Algorithm for Path Planning in Autonomous Parking System Based on Multi-Stage Dynamic Optimization. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2023, 24, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; Tumova, J.; Belta, C.; Rus, D. Optimal path planning under temporal logic constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 3288–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi, S.; Nguyen, D.V.; Kuhnert, K.D. Guided Hybrid A-star Path Planning Algorithm for Valet Parking Applications. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Control, Automation and Robotics, Beijing, China, 19–22 April 2019; pp. 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, X. An Autonomous Valet Parking Algorithm for Path Planning and Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE 96th Vehicular Technology Conference, London, UK, 26–29 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guan, X.; Ren, W.; Li, G. Improved Hybrid A* Path Planning Method for Spherical Mobile Robot Based on Pendulum. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatif, M.; Adeel, U.; Basiri, A.; Mariani, V.; Iannelli, L.; Glielmo, L. Deep Learning Based Path-Planning Using CRNN and A* for Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Innovations in Computing Research; Daimi, K., Al Sadoon, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Jiang, F.J.; Ren, X.; Xie, L.; Johansson, K.H. Reachability-based Human-in-the-Loop Control with Uncertain Specifications. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 1880–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Maity, D.; Baras, J.S. Optimal mission planner with timed temporal logic constraints. In Proceedings of the European Control Conference, Linz, Austria, 15–17 July 2015; pp. 759–764. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Maity, D.; Baras, J.S. Timed automata approach for motion planning using metric interval temporal logic. In Proceedings of the European Control Conference, Aalborg, Denmark, 29 June–1 July 2016; pp. 690–695. [Google Scholar]

- Maity, D.; Baras, J.S. Event-triggered controller synthesis for dynamical systems with temporal logic constraints. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 27–29 June 2018; pp. 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, L.; Maity, D.; Baras, J.S.; Dimarogonas, D.V. Event-triggered feedback control for signal temporal logic tasks. In Proceedings of the Conference on Decision and Control, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 17–19 December 2018; pp. 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Dolgov, D.; Thrun, S.; Montemerlo, M.; Diebel, J. Path planning for autonomous vehicles in unknown semi-structured environments. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2010, 29, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, X.; Borrelli, F. Autonomous Parking of Vehicle Fleet in Tight Environments. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 1–3 July 2020; pp. 3035–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Tan, K.K. Autonomous Reverse Parking System Based on Robust Path Generation and Improved Sliding Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 16, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, B.; Deutscher, J.; Grodde, S. Trajectory generation and feedforward control for parking a car. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Aided Control System Design, IEEE International Conference on Control Applications, IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Control, Andras Varga, PC, USA, 4–6 October 2006; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, B.; Xuan, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, T.; Qian, L. A trajectory planning method for autonomous valet parking via solving an optimal control problem. Sensors 2020, 20, 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shao, Z. A Unified Motion Planning Method for Parking an Autonomous Vehicle in the Presence of Irregularly Placed Obstacles. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2015, 86, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohata, A.; Mio, M. Parking Control Based on Nonlinear Trajectory Control for Low Speed Vehicles. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Electronics, Control and Instrumentation, Kobe, Japan, 28 October–1 November 1991; pp. 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, B.; Deutscher, J.; Grodde, S. Continuous Curvature Trajectory Design and Feedforward Control for Parking a Car. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2007, 15, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bravo, F.; Cuesta, F.; Ollero, A.; Viguria, A. Continuous Curvature Path Generation Based on β-Spline Curves for Parking Manoeuvres. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2008, 56, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobieva, H.; Minoiu-Enache, N.; Glaser, S.; Mammar, S. Geometric Continuous-Curvature Path Planning for Automatic Parallel Parking. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control, Evry, France, 10–12 April 2013; pp. 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. Optimal Approach for Autonomous Parallel Parking of Nonholonomic Car-Like Vehicle. Master’s Thesis, State University of New York at Buffalo, Department of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering, Buffalo, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Patten, W.N.; Wu, H.C.; Cai, W. Perfect Parallel Parking Via Pontryagin’s Principle. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1994, 116, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondak, K.; Hommel, G. Computation of Time Optimal Movements for Autonomous Parking of Non-Holonomic Mobile Platforms. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–26 May 2001; pp. 2698–2703. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Wang, K.; Shao, Z. Time-Optimal Maneuver Planning in Automatic Parallel Parking Using a Simultaneous Dynamic Optimization Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 3263–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobieva, H.; Glaser, S.; Minoiu-Enache, N.; Mammar, S. Automatic Parallel Parking in Tiny Spots: Path Planning and Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 16, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Meng, X.; Fu, T. Automatic Parking Trajectory Planning Based on Random Sampling and Nonlinear Optimization. J. Frankl. Inst. 2023, 360, 9579–9601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zips, P.; Böck, M.; Kugi, A. Optimisation Based Path Planning for Car Parking in Narrow Environments. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2016, 79, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zips, P.; Böck, M.; Kugi, A. Fast Optimization Based Motion Planning and Path-Tracking Control for Car Parking. In Proceedings of the 9th IFAC Symposium on Nonlinear Control Systems, Toulouse, France, 4–6 September 2013; pp. 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, J.; Sha, W.; Niu, R. Autonomous Parking Path Tracking Control Based on Interference Suppression. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 109528–109538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qin, Z.; Hu, M.; Bian, Y.; Peng, X. Path Tracking Controller Design of Automated Parking Systems via NMPC with an Instructible Solution. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, D.; Howard, T.M.; Likhachev, M. Motion Planning in Urban Environments: Part I. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 1063–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, D.; Howard, T.M.; Likhachev, M. Motion Planning in Urban Environments: Part II. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 1070–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, P. A Feasible Parking Algorithm in Form of Path Planning and Following. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Robotics and Artificial Intelligence, (RICAI), Shanghai, China, 20–22 September 2019; pp. 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.R.; Vineet, V.; Roth, S.; Koltun, V. Playing for Data: Ground Truth from Computer Games. arXiv 2016, arXiv:cs.CV/1608.02192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadnis, M. Latest Review of Parking Problems and Intelligent Parking System for Smart City. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2016, 7, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Mazda USA. 2018 Mazda6 Owner’s Manual. Available online: https://www.mazdausa.com/static/manuals/2018/mazda6/contents/05200100.html. (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Diehl, C.; Makarow, A.; Rösmann, C.; Bertram, T. Time-Optimal Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for Radar-based Automated Parking. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su-Jin, P.; Lebeltel, O.; Laugier, C. Parking a car using Bayesian Programming. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision, Singapore, 2–5 December 2002; Volume 2, pp. 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Wang, Y. Long-Horizon Motion Planning for Autonomous Vehicle Parking Incorporating Incomplete Map Information. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 8135–8142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalašová, A.; Čulík, K.; Poliak, M.; Otahálová, Z. Smart Parking Applications and Its Efficiency. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.F.; Özguner, Ü. A Parking Algorithm for an Autonomous Vehicle. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 4–6 June 2008; pp. 1155–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Paromtchik, I.E.; Laugier, C. Motion Generation and Control for Parking an Autonomous Vehicle. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Minneapolis, MI, USA, 22–28 April 1996; pp. 3117–3122. [Google Scholar]

- Paromtchik, I.E.; Laugier, C. Automatic Parallel Parking and Returning to Traffic Maneuvers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Grenoble, France, 11 September 1997; pp. 3117–3122. [Google Scholar]

- Sedighi, S.; Nguyen, D.V.; Kuhnert, K.D. Implementation of a Parking State Machine on Vision-Based Auto Parking Systems for Perpendicular Parking Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies, Paris, France, 23–26 April 2019; pp. 1711–1716. [Google Scholar]

- Kümmerle, R.; Hähnel, D.; Dolgov, D.; Thrun, S.; Burgard, W. Autonomous Driving in a Multi-Level Parking Structure. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 3395–3400. [Google Scholar]

- Ahad, D.M.A.; Sarkar, A.A.; Mannan, M.A. Mathematical Modeling and to carry out a prototype helpmate differential drive robot for hospital purpose. Am. Acad. Sch. Res. J. 2014, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmett, H.; Buerki, M.; Paz, L.; Pinies, P.; Furgale, P.; Posner, I.; Newman, P. Integrating Metric and Semantic Maps for Vision-Only Automated Parking. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 2159–2166. [Google Scholar]

- Schiotka, A.; Suger, B.; Burgard, W. Robot Localization with Sparse Scan-Based Maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 September 2017; pp. 642–647. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Do, Q.H.; Mita, S. Unified Path Planner for Parking an Autonomous Vehicle based on RRT. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 5622–5627. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.; Chung, W. Performance Analysis of Path Planners for Car-Like Vehicles Toward Automatic Parking Control. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2014, 7, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.H.; Mita, S.; Yoneda, K. A Practical and Optimal Path Planning for Autonomous Parking Using Fast Marching Algorithm and Support Vector Machine. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2013, E96-D, 2795–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Guan, H.; Zhang, H.L.; Jia, X.; Zhan, J. Multi-maneuver Vertical Parking Path Planning and Control in a Narrow Space. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2022, 149, 103964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobieva, H.; Glaser, S.; Minoiu-Enache, N.; Mammar, S. Automatic Parallel Parking with Geometric Continuous-Curvature Path Planning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Dearborn, MI, USA, 8–11 June 2014; pp. 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobieva, H.; Glaser, S.; Minoiu-Enache, N.; Mammar, S. Geometric Path Planning for Automatic Parallel Parking in Tiny Spots. In Proceedings of the 13th IFAC Symposium on Control in Transportation Systems, Sofia, Bulgaria, 12–14 September 2012; pp. 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Liu, S. RRT based Path Planning for Autonomous Parking of Vehicle. In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th Data Driven Control and Learning Systems Conference, Enshi, China, 25–27 May 2018; pp. 627–632. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwata, Y.; Fiore, G.A.; Teo, J.; Frazzoli, E.; How, J.P. Motion Planning for Urban Driving using RRT. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 1681–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Jhang, J.H.; Lian, F.L.; Hao, Y.H. Human-like motion planning for autonomous parking based on revised bidirectional rapidly-exploring random tree* with Reeds-Shepp curve. Asian J. Control 2021, 23, 1146–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgov, D.; Thrun, S. Autonomous Driving in Semi-Structured Environments: Mapping and Planning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 3407–3414. [Google Scholar]

- AbuJabal, N.; Baziyad, M.; Fareh, R.; Brahmi, B.; Rabie, T.; Bettayeb, M. A Comprehensive Study of Recent Path-Planning Techniques in Dynamic Environments for Autonomous Robots. Sensors 2024, 24, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fersman, E.; Krcal, P.; Pettersson, P.; Yi, W. Task Automata: Schedulability, Decidability and Undecidability. Inf. Comput. 2007, 205, 1149–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, D.; Baras, J.S. Motion Planning in Dynamic Environments with Bounded Time Temporal Logic Specifications. In Proceedings of the 2015 Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation, Torremolinos, Spain, 16–19 June 2015; pp. 940–946. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, C.; Katoen, J.P. Principles of Model Checking; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska, M.; Norman, G.; Parker, D. PRISM 4.0—Verification of Probabilistic Real-Time Systems. In Computer Aided Verification, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6806, pp. 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, G.J. The Model Checker SPIN. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1997, 23, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duret-Lutz, A.; Lewkowicz, A.; Fauchille, A.; Michaud, T.; Renault, E.; Xu, L. Spot 2.0—A Framework for LTL and ω-automata Manipulation. In Automated Technology for Verification and Analysis, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 9938, pp. 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.G.; Pettersson, P.; Yi, W. UPPAAL in a Nutshell. Int. J. Softw. Tools Technol. Transf. 1997, 1, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| a | c | d | b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| d | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| b | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | c |

| Future State | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0a | 0c | 0d | 0b | 1a | 1c | 1d | 1b | 2a | 2c | 2d | 2b | ||

| Present State | 0a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0c | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0d | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0b | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Future State | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0a |  | 0d | 0b |  |  |  |  | 2a |  | 2d | 2b | ||

| Present State |  | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0d | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0b | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Future State | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0a | 0d | 0b | 1c | 2a | 2d | 2b | ||

| Present State | 0a | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0d | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Scenario | Mean Total Computation Time (s) | Replanning Latency (s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | (post-replan), | |

| (PA rebuild) | ||

| 3 | (post-replan), | |

| (PA rebuild) | ||

| 4 | (post-replan), | |

| (PA rebuild) | ||

| 5 | (post-replan), | |

| (PA rebuild) |

| Method | Task 1 (Initial Build) | Task 2 (Replanning) | Total Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Our Matrix-Based Method | s | s | s |

| Traditional Method | s | s | s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahad, D.M.A.; Maity, D. Matrix-Guided Safe Motion Planning for Smart Parking Systems. Robotics 2025, 14, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14110171

Ahad DMA, Maity D. Matrix-Guided Safe Motion Planning for Smart Parking Systems. Robotics. 2025; 14(11):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14110171

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhad, Dewan Mohammed Abdul, and Dipankar Maity. 2025. "Matrix-Guided Safe Motion Planning for Smart Parking Systems" Robotics 14, no. 11: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14110171

APA StyleAhad, D. M. A., & Maity, D. (2025). Matrix-Guided Safe Motion Planning for Smart Parking Systems. Robotics, 14(11), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14110171