Steric and Electronic Effects in the Enzymatic Catalysis of Choline-TMA Lyase

Abstract

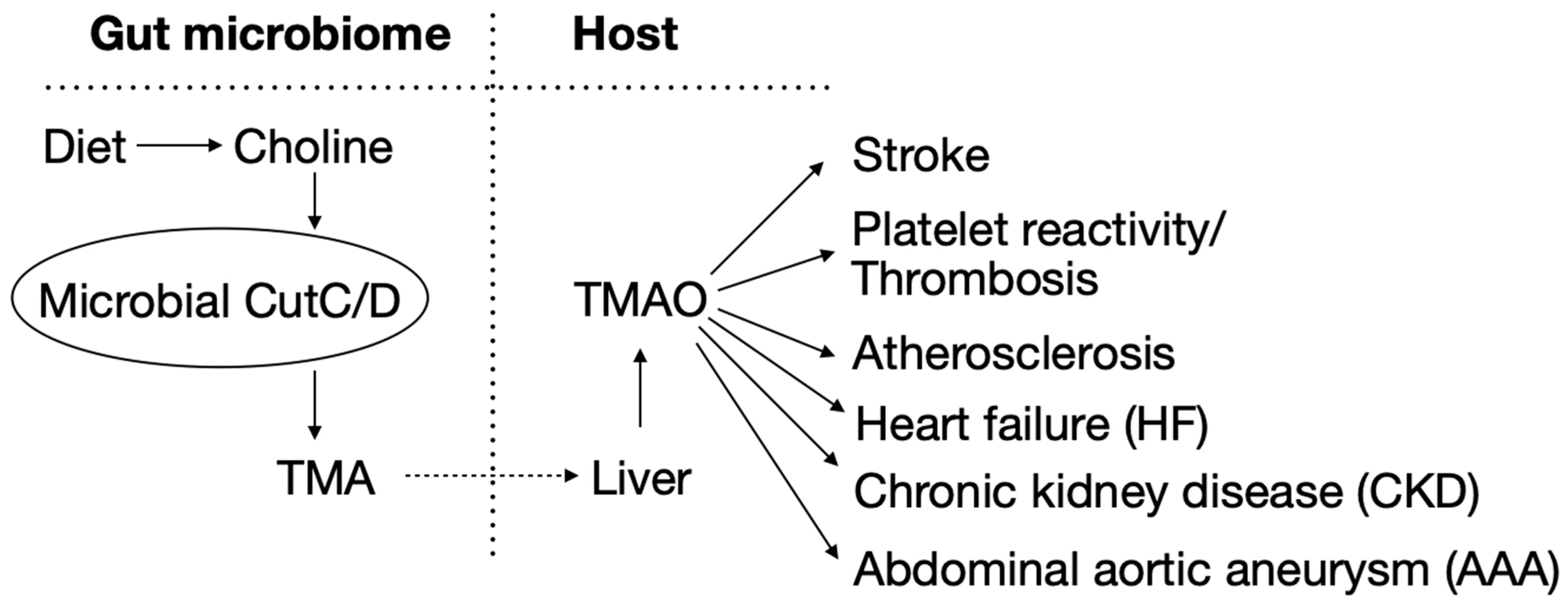

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Quantum Mechanical Calculations

2.2. Combined Quantum Mechanical–Molecular Mechanics Calculations

3. Results

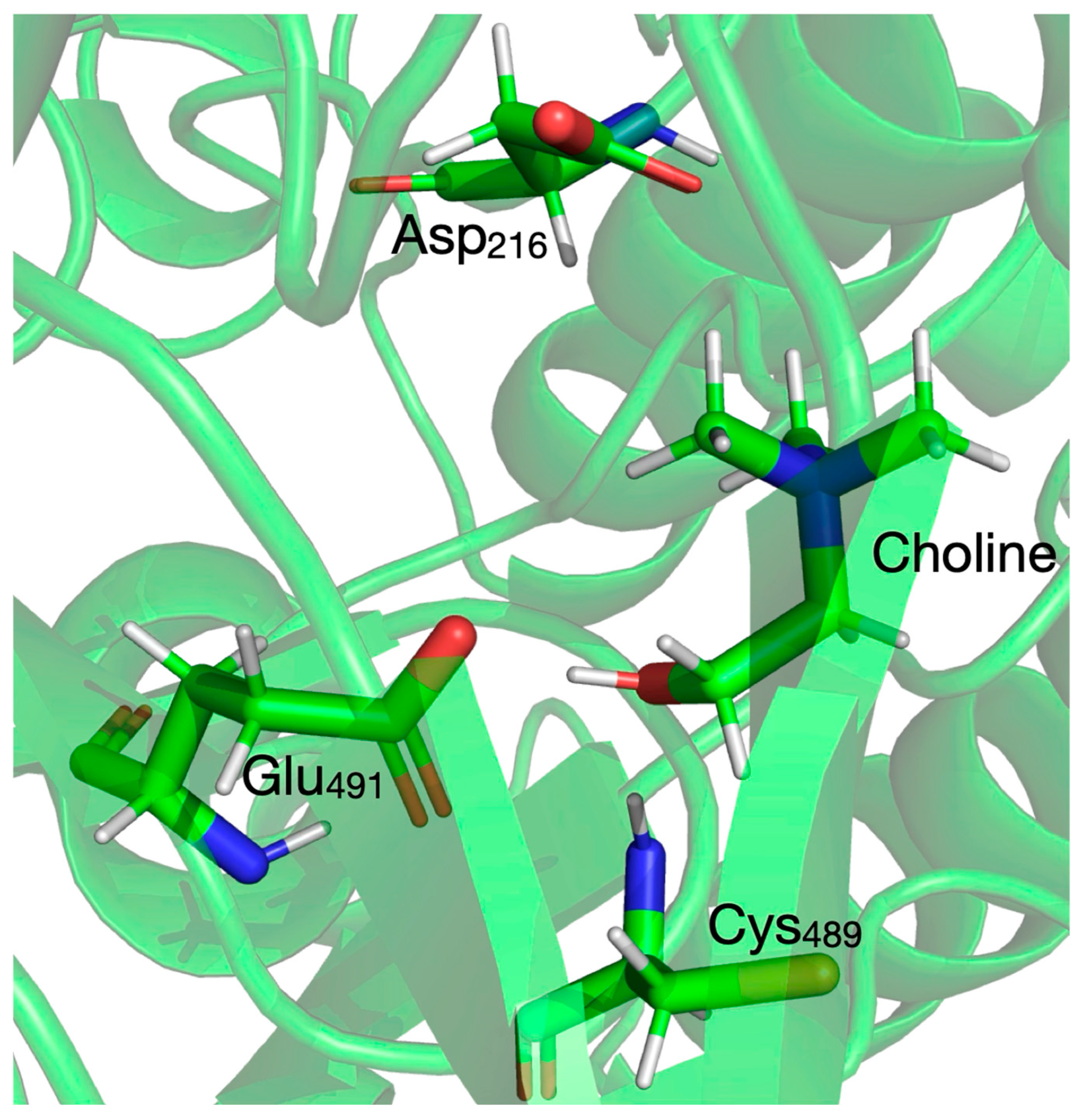

3.1. Selecting the Size of the QM System

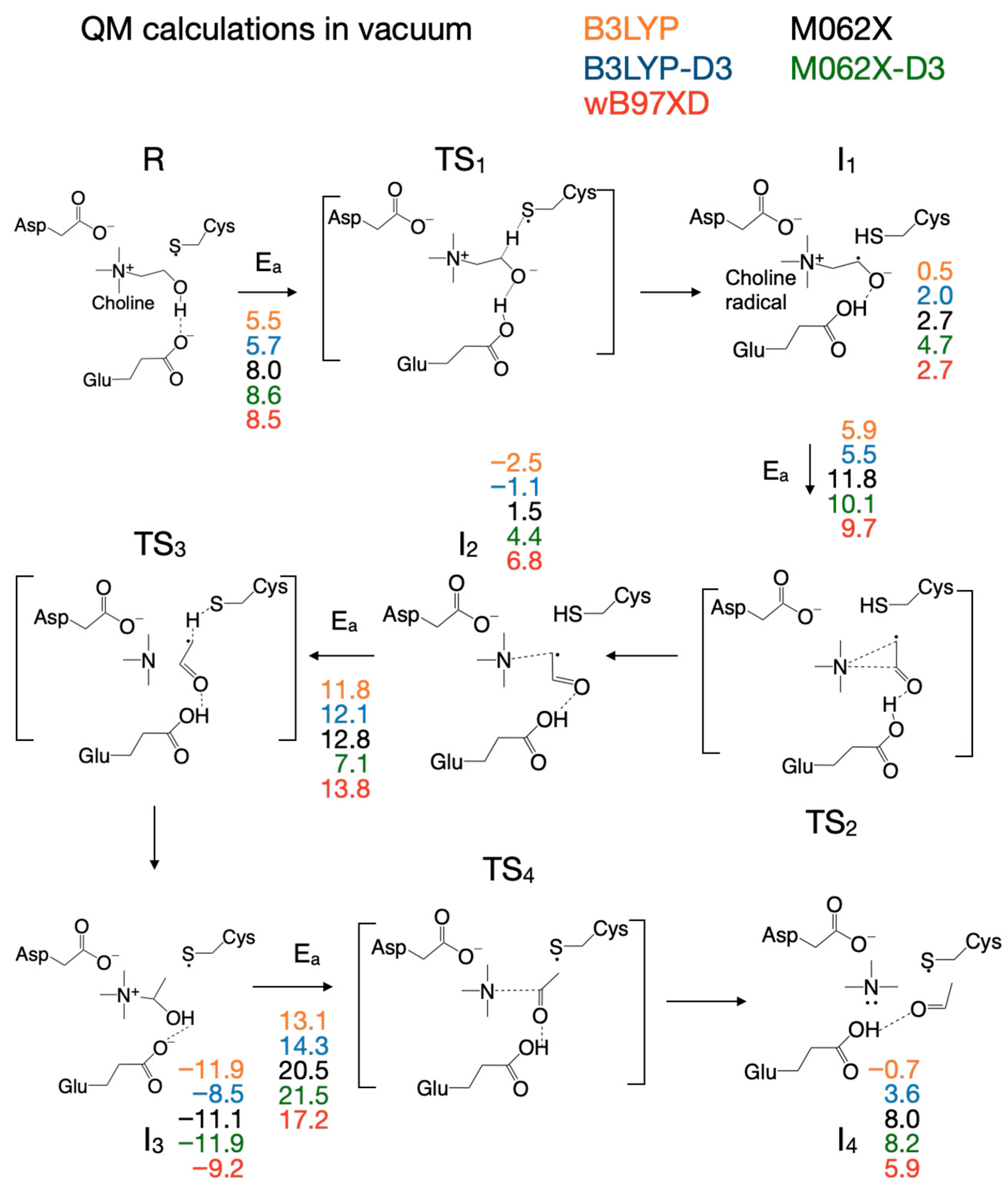

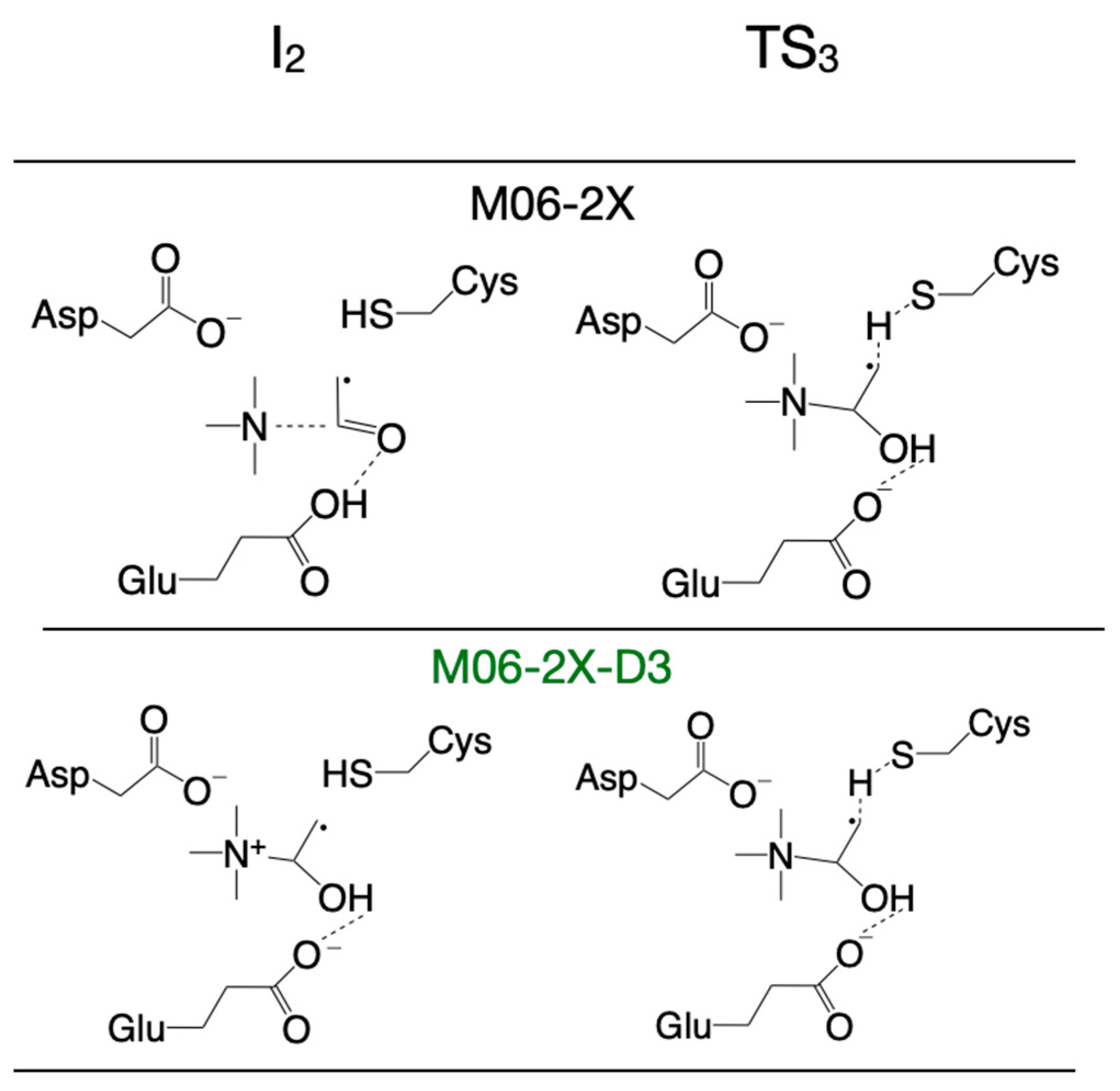

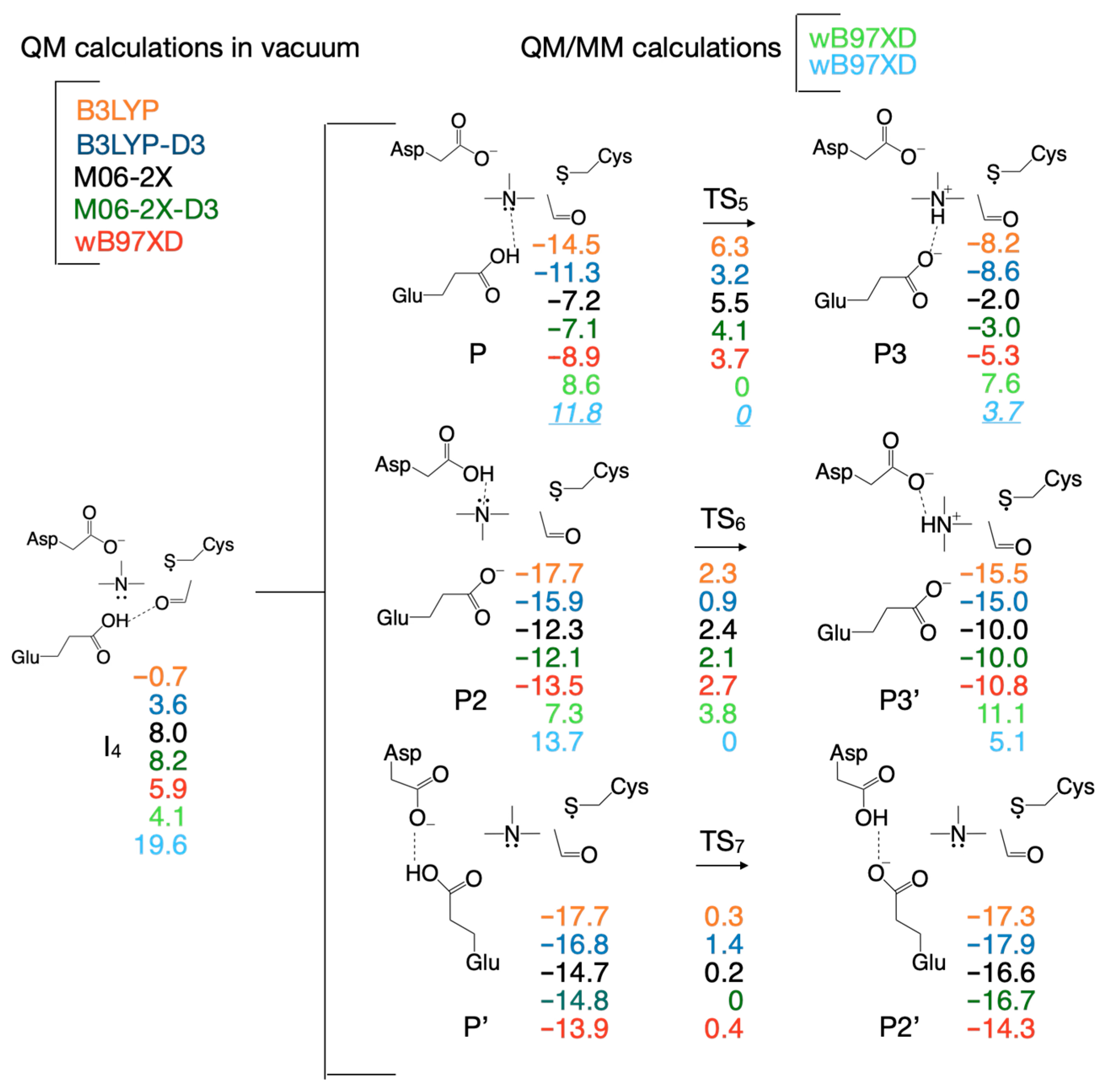

3.2. Selecting the DFT Functional for Exploring the Reaction Mechanism

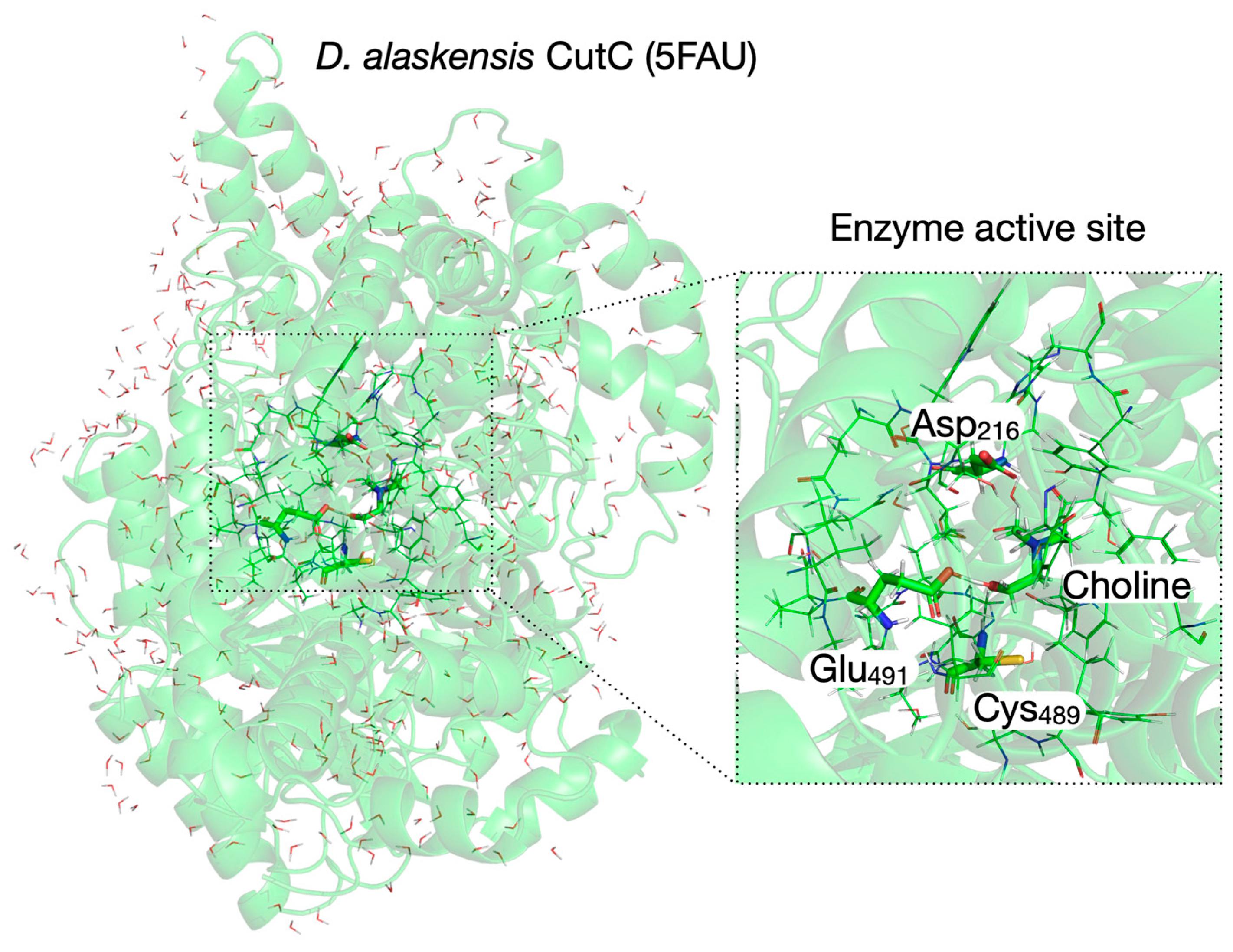

3.3. Setup of the QM/MM System for Reaction Mechanism Calculations Within Enzyme Environment

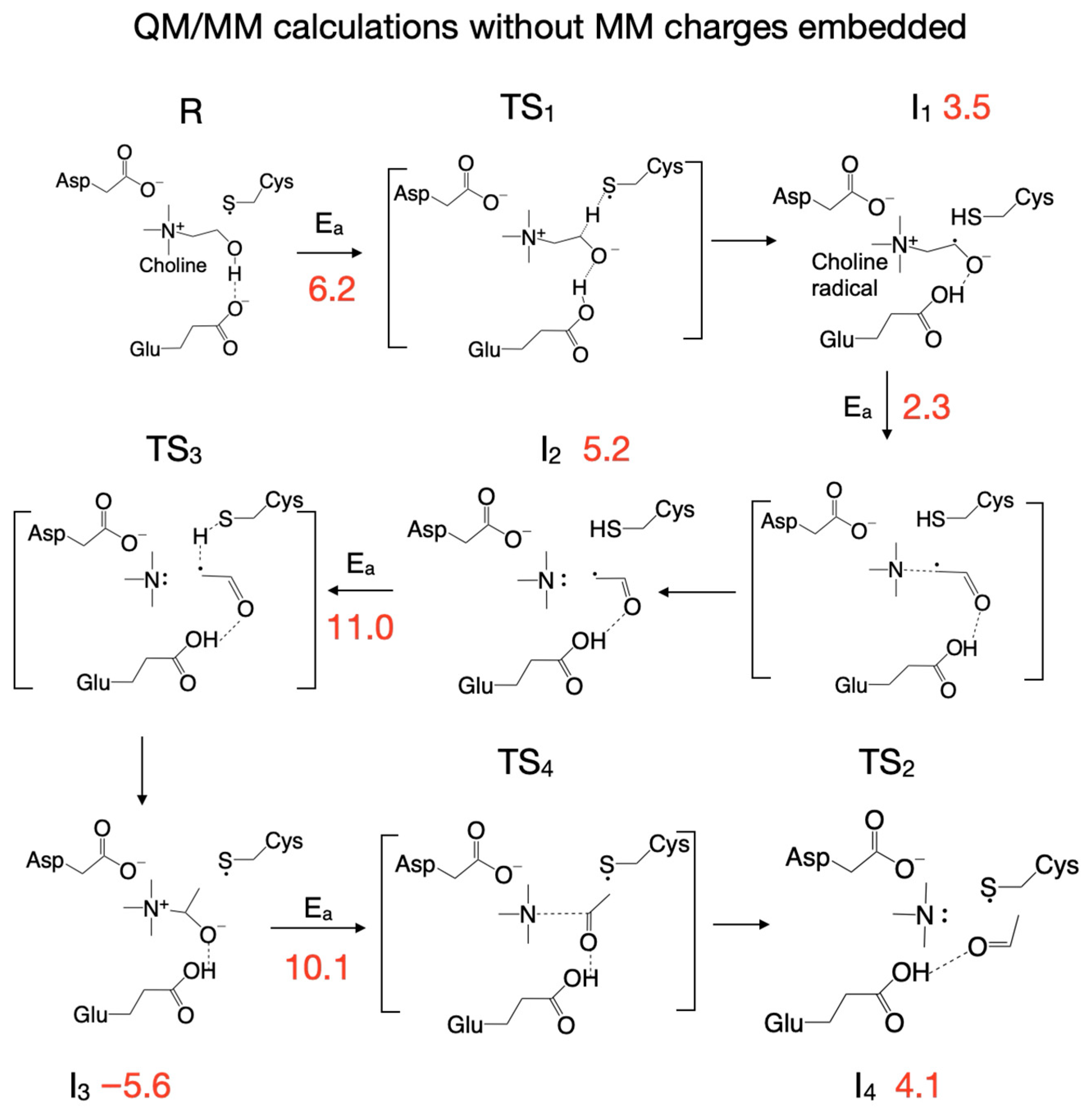

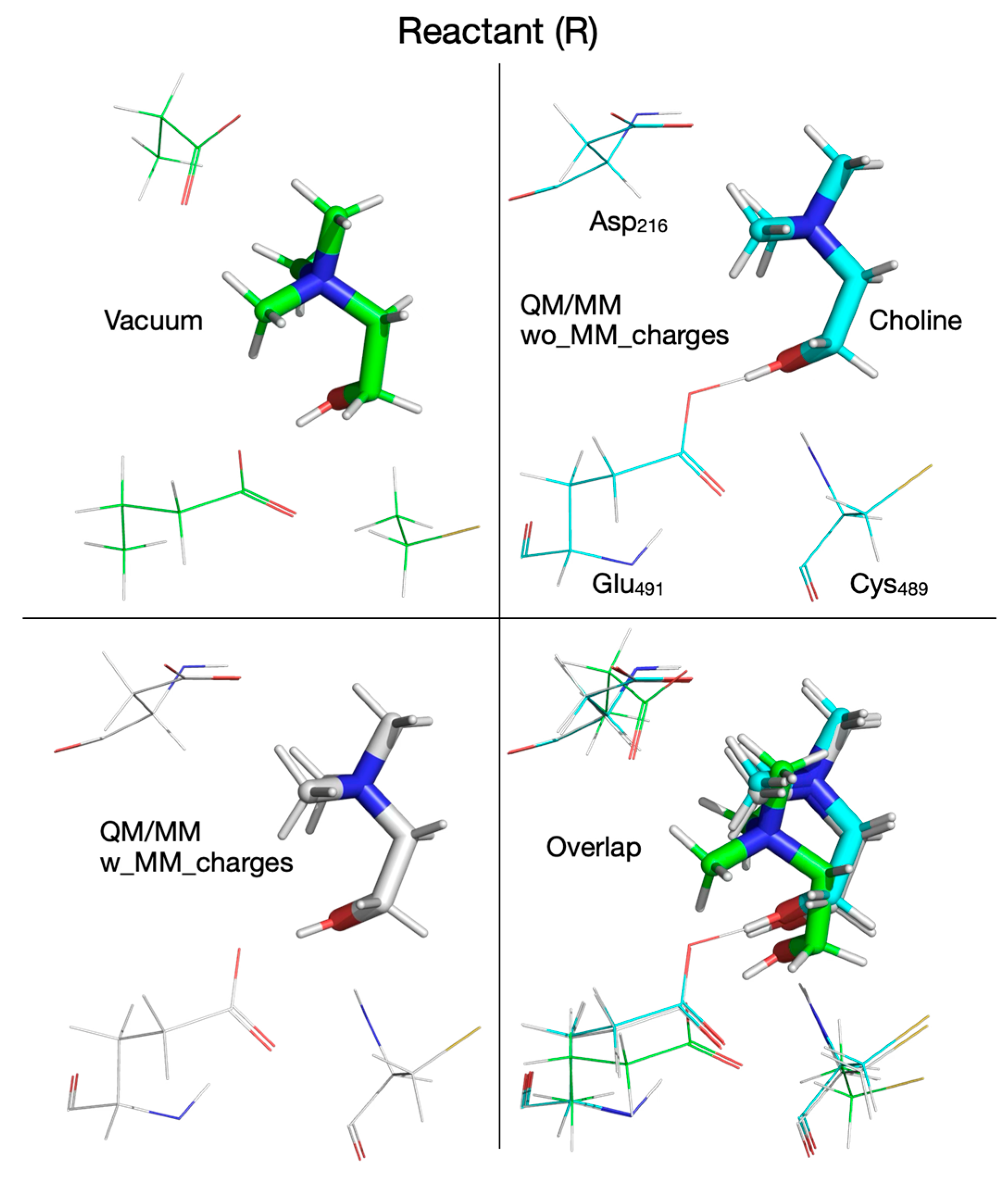

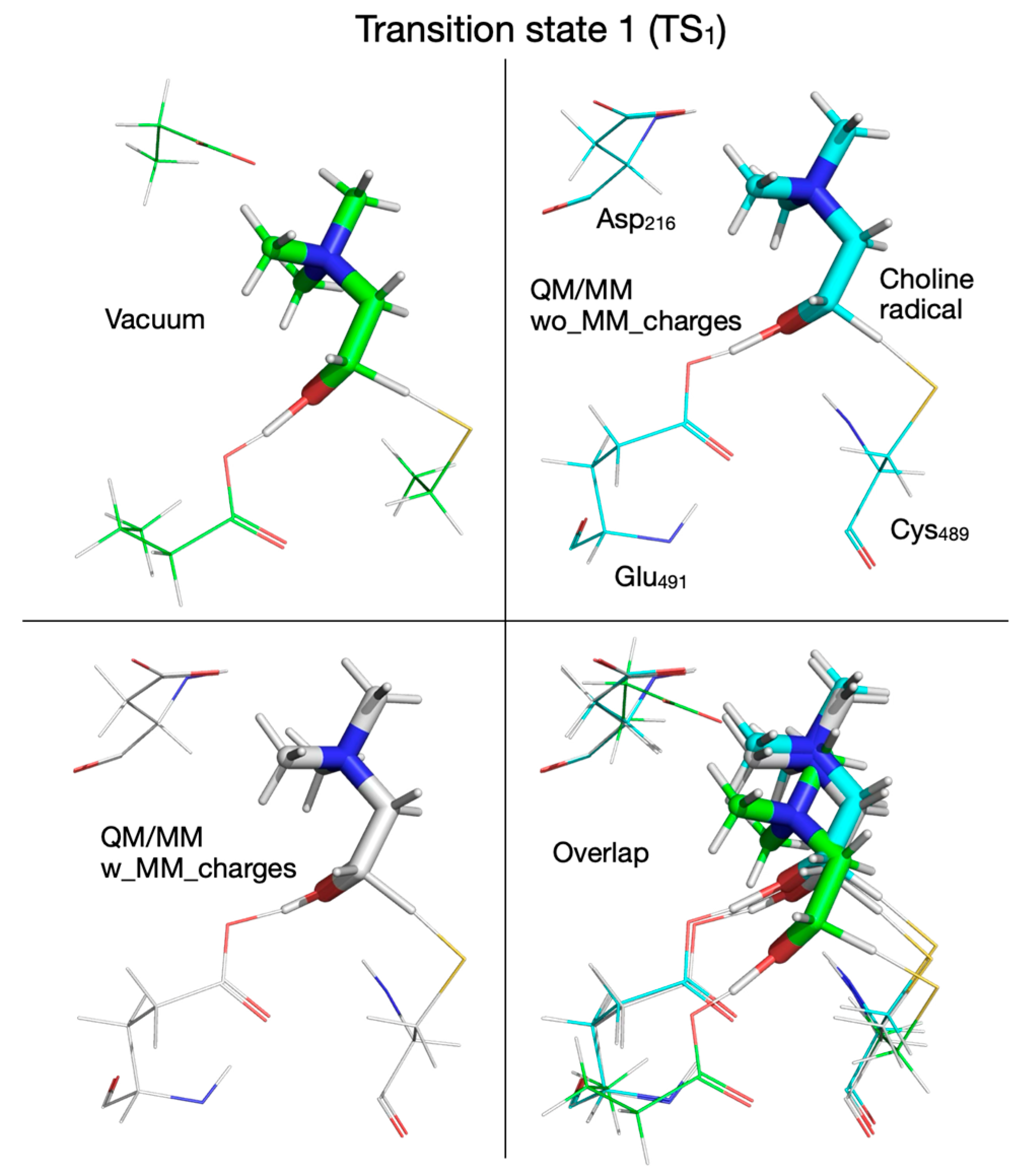

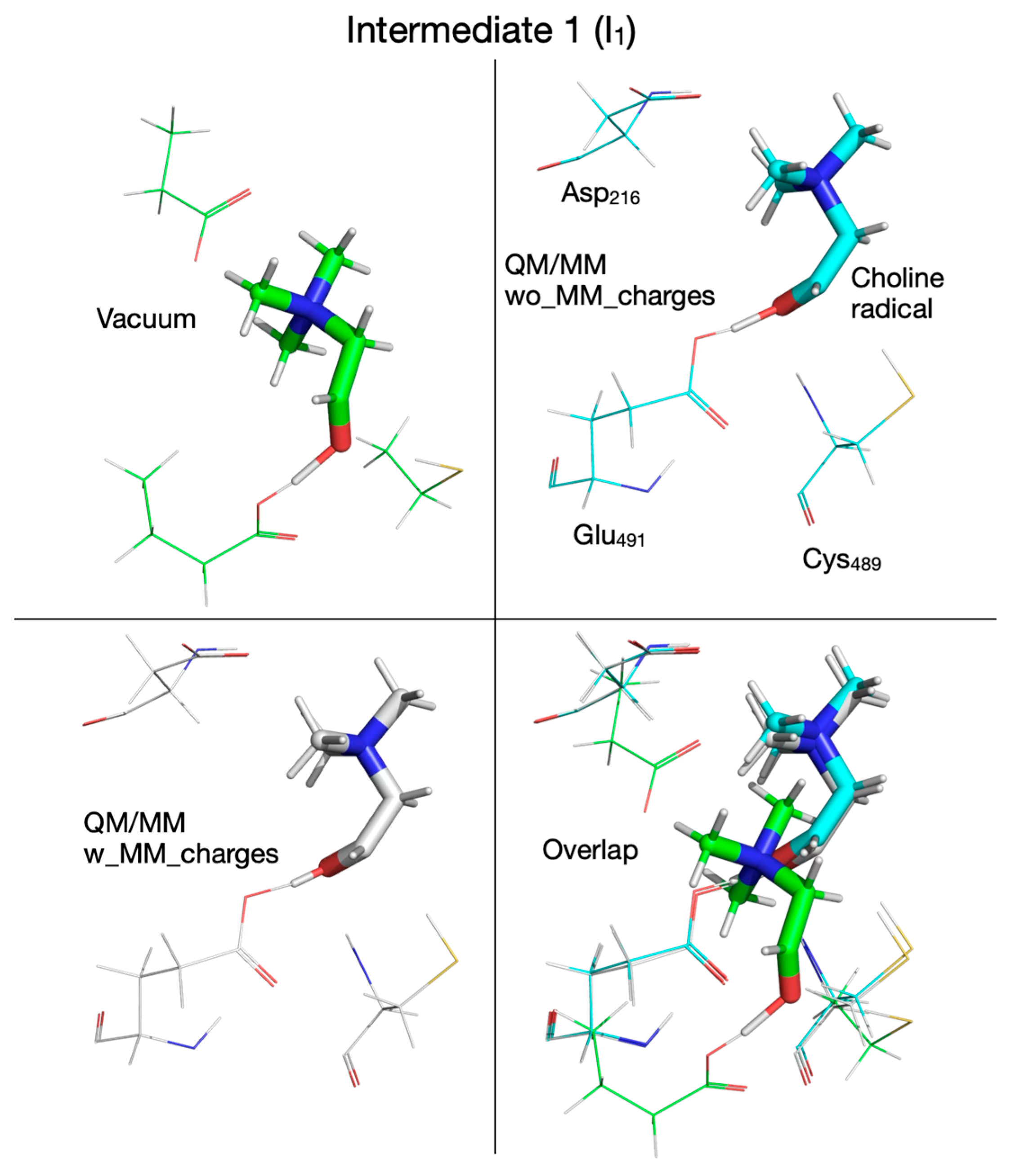

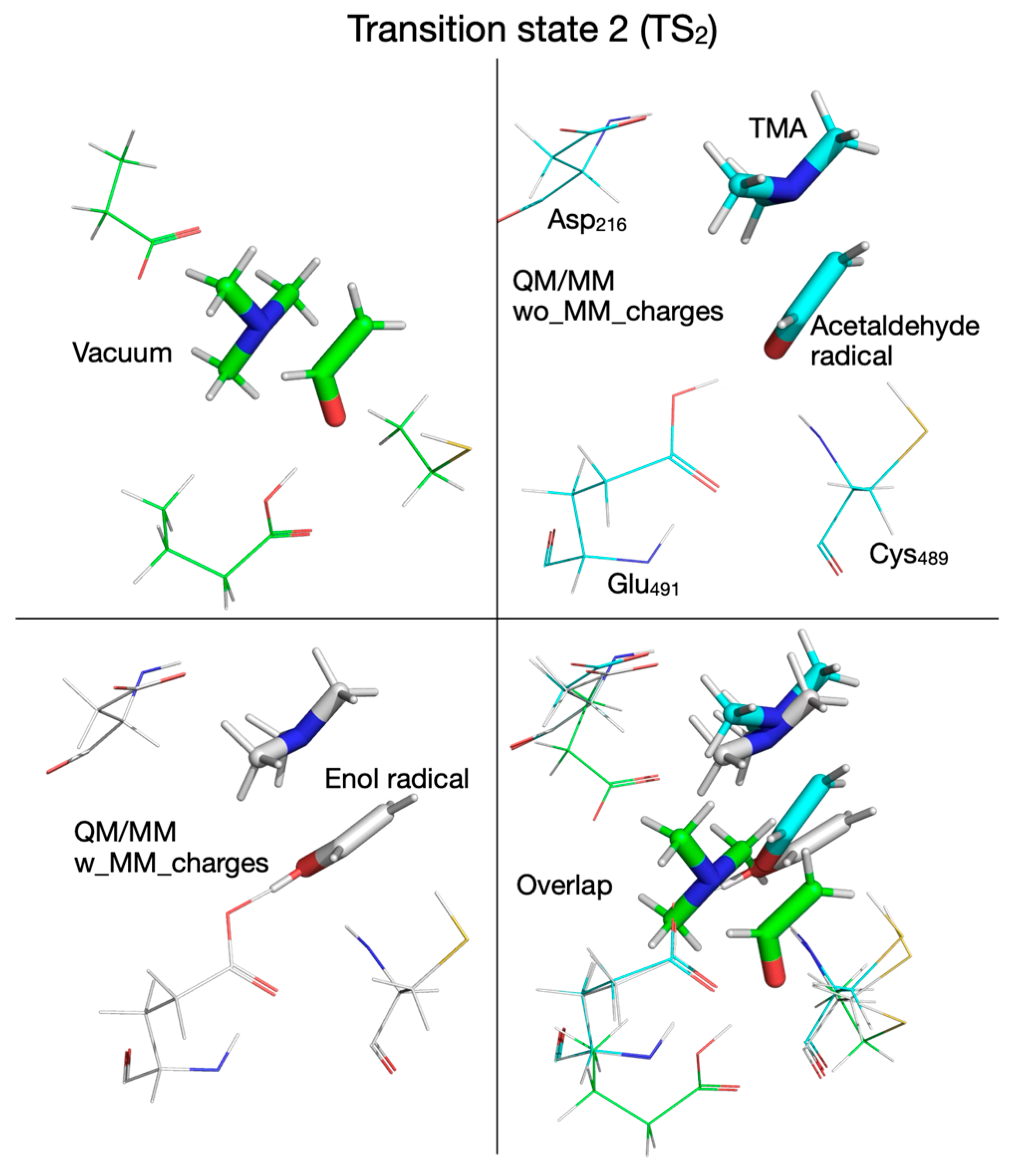

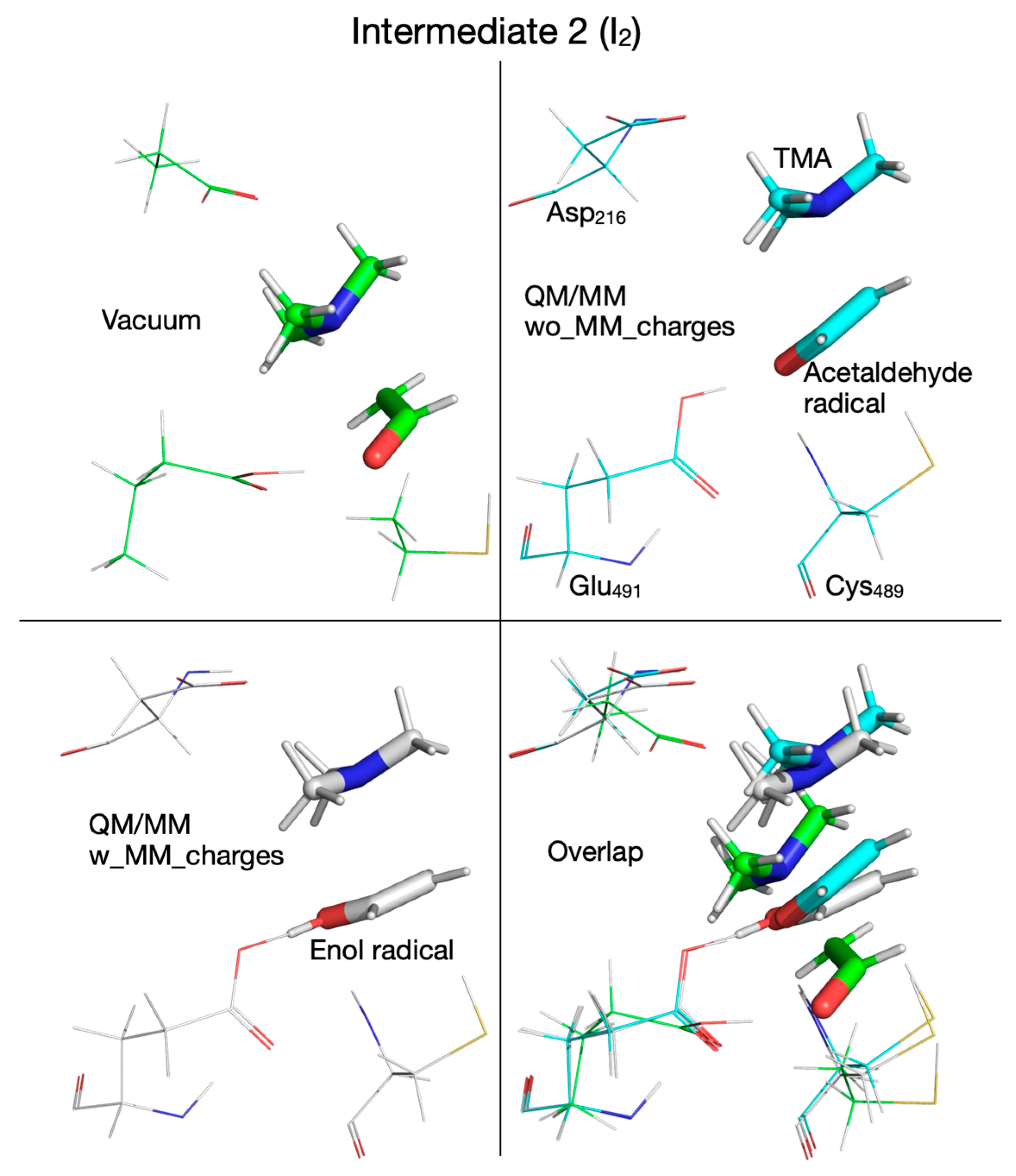

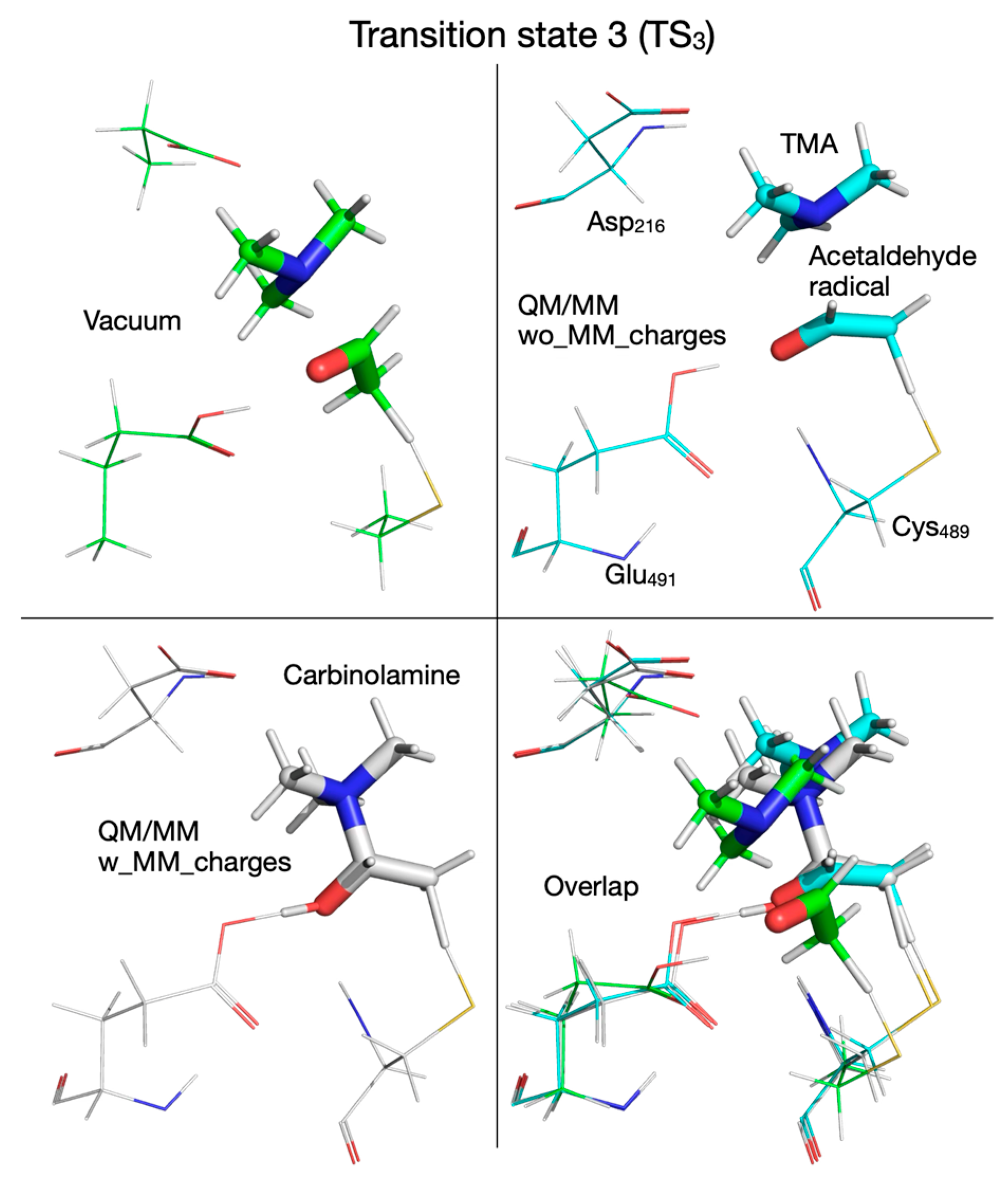

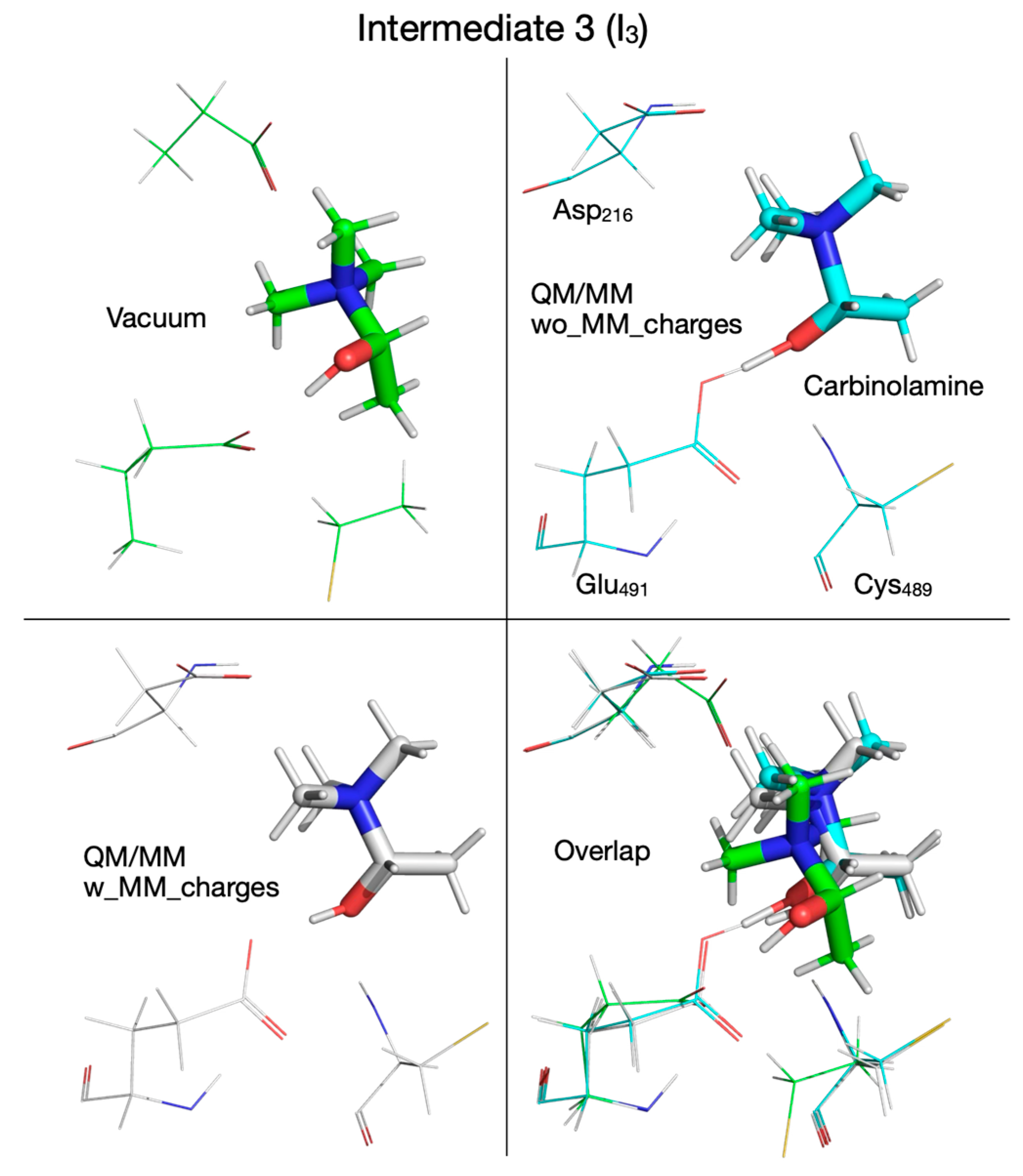

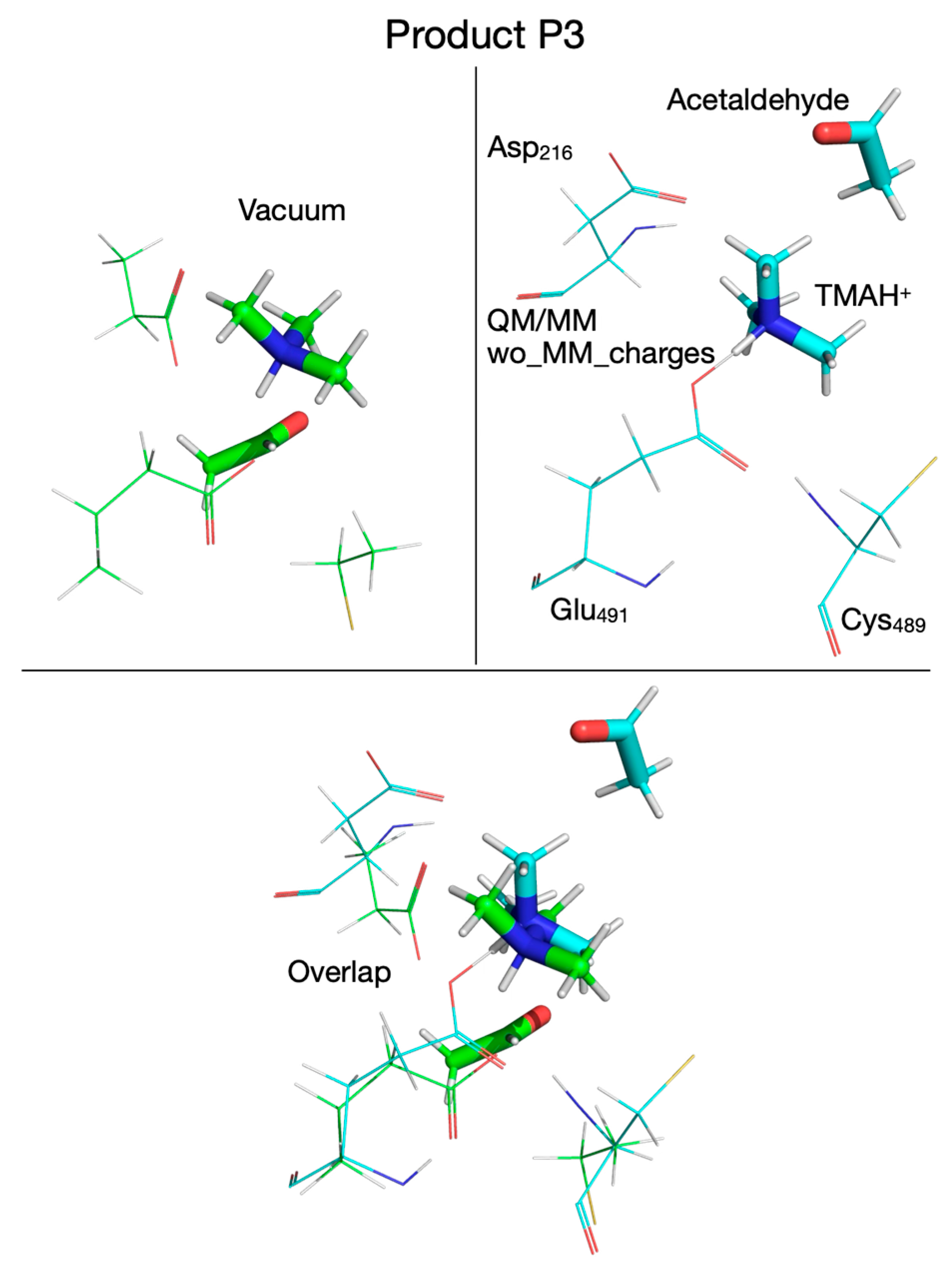

3.4. Reaction Mechanism from Exploring the PES with QM/MM Calculations Performed Without Including MM Partial Atomic Charges into the QM Subsystem

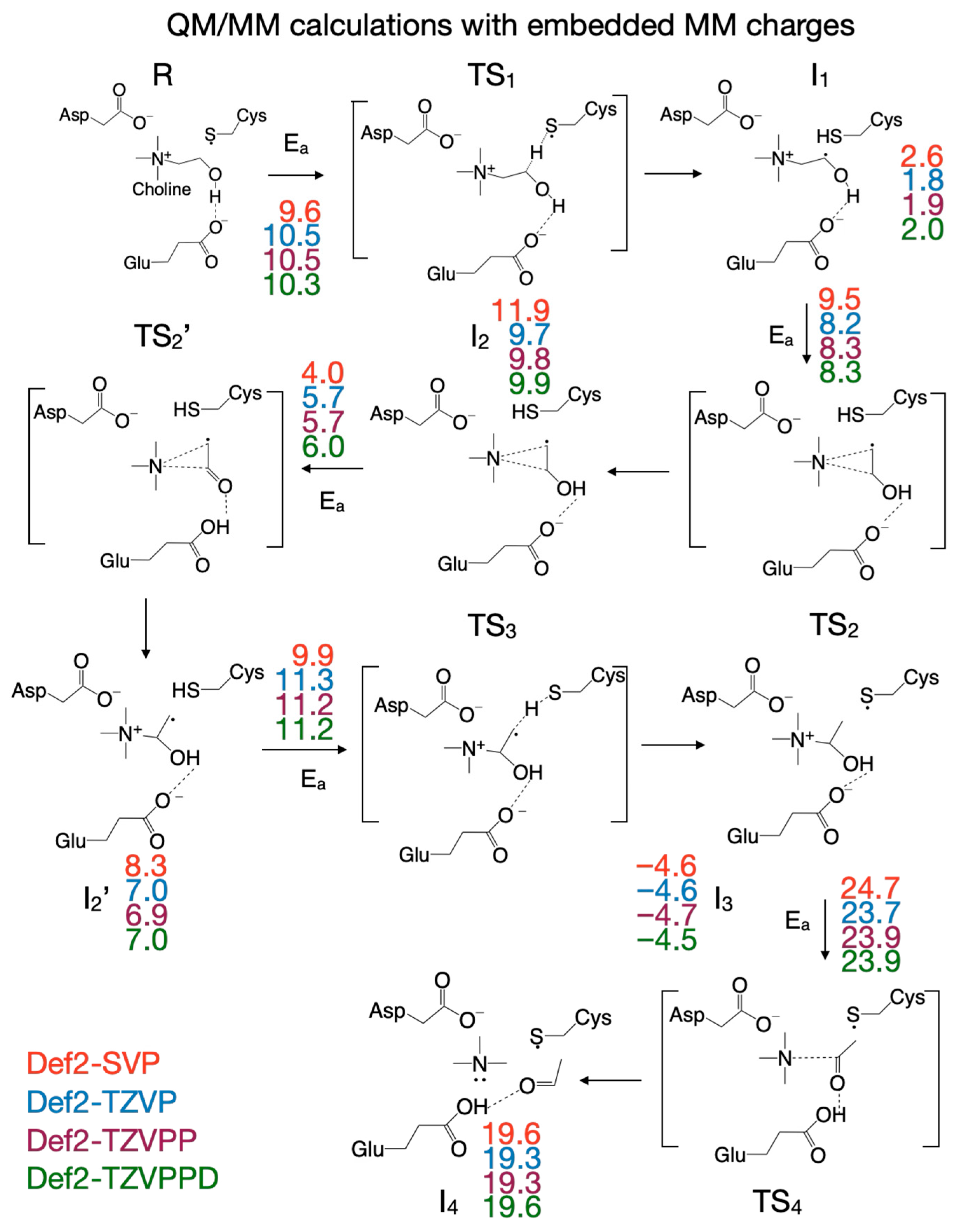

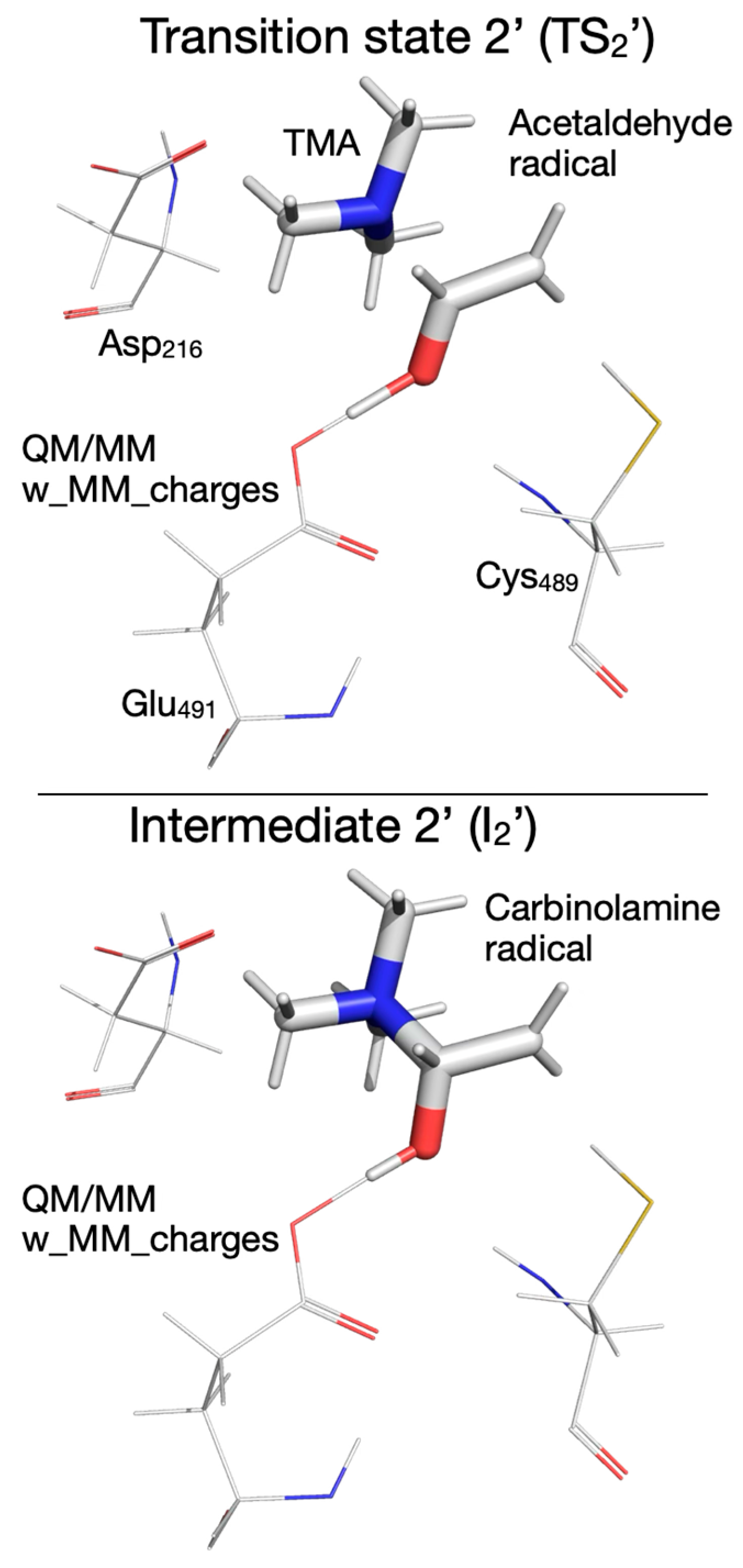

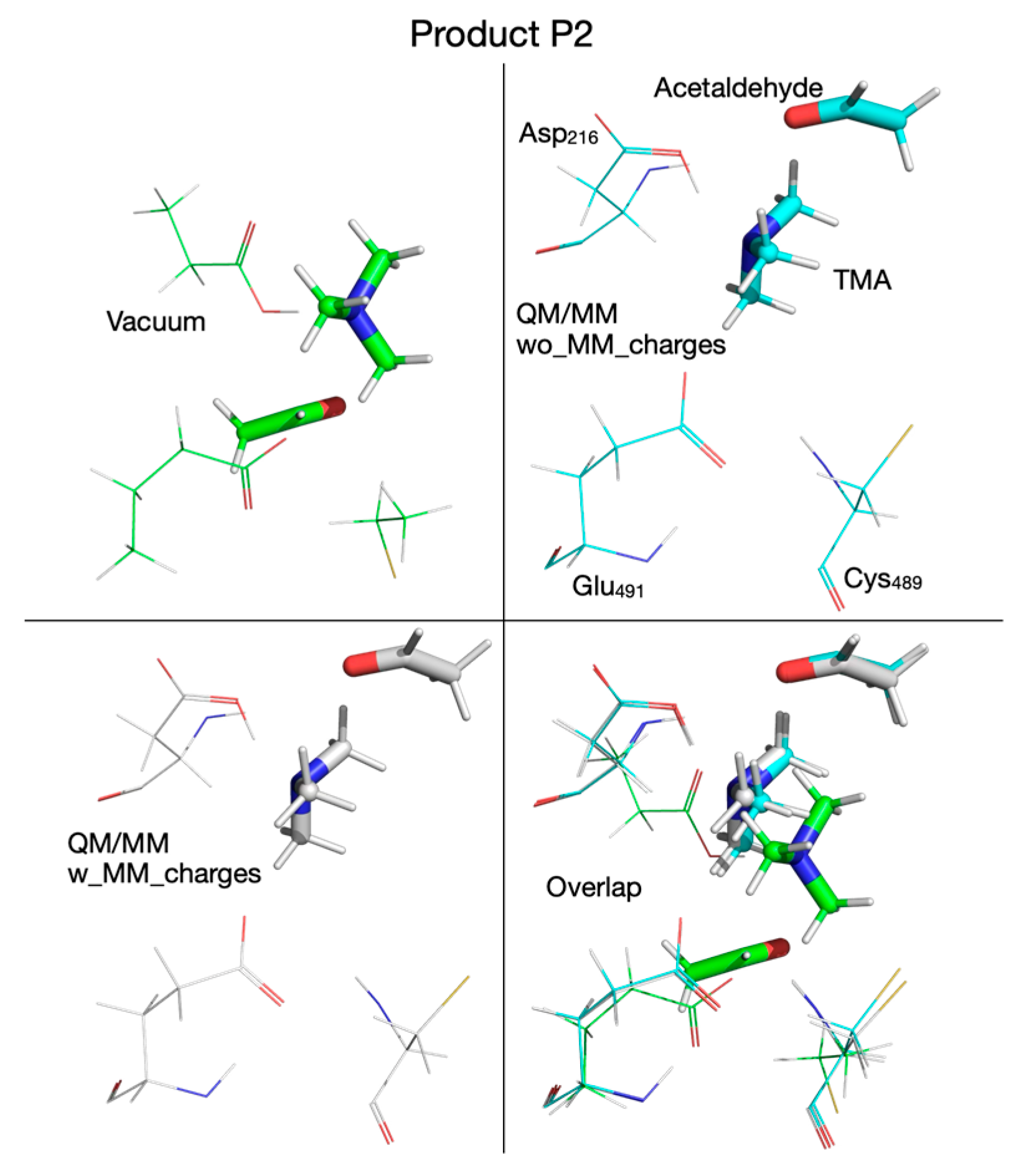

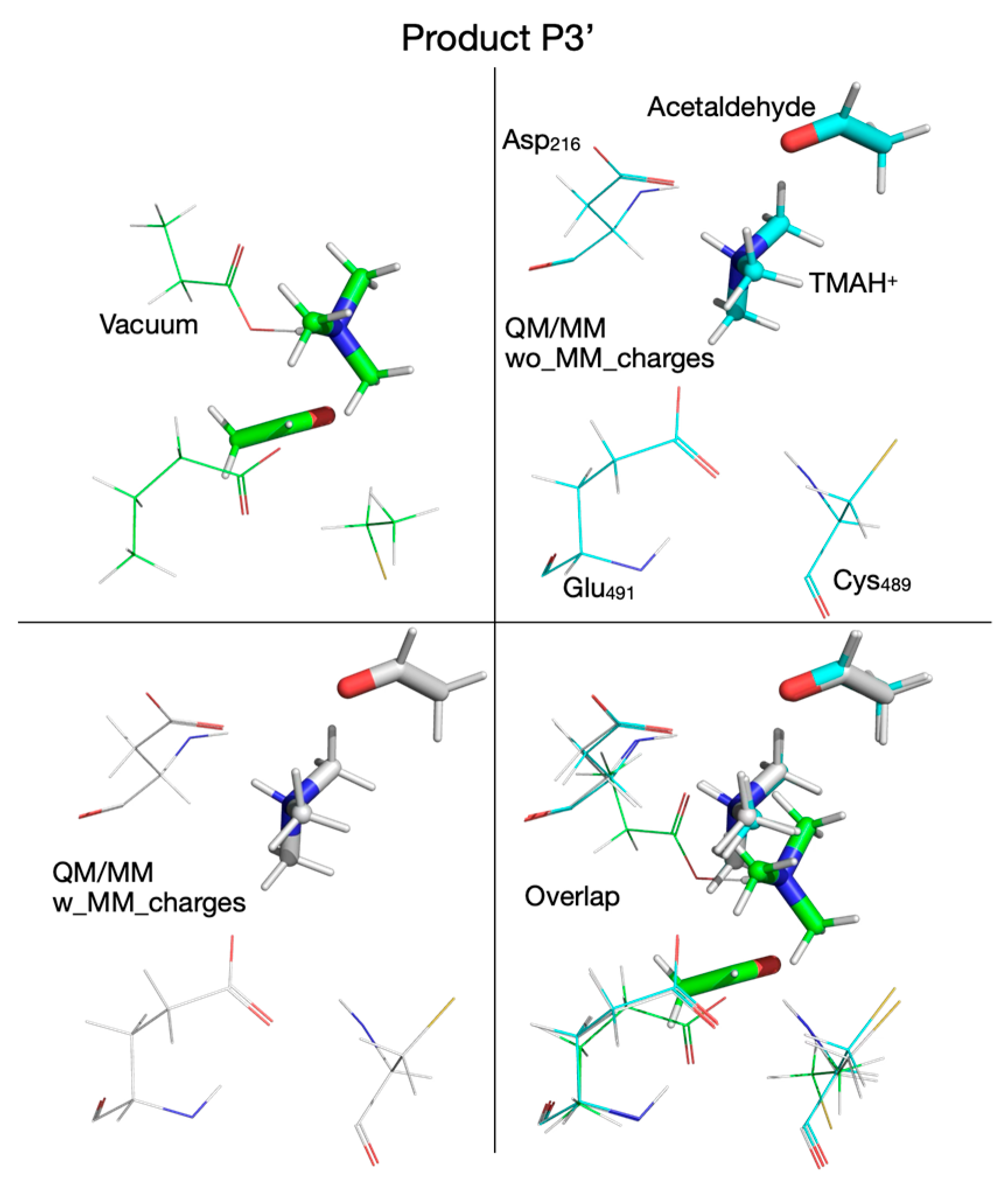

3.5. Reaction Mechanism from Exploring the PES with QM/MM Calculations Performed by Including the MM Partial Atomic Charges into the QM Subsystem

3.6. Steric and Electronic Effects of the Enzyme Environment on the Choline-TMA Lyase Reaction Mechanism

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, W.H.W.; Bäckhed, F.; Landmesser, U.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2089–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.A.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.M.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Koeth, R.A.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal Microbial Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine and Cardiovascular Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, S.; Heidrich, B.; Pieper, D.H.; Vital, M. Uncovering the trimethylamine-producing bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Microbiome 2017, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craciun, S.; Balskus, E.P. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21307–21312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.J.; de Aguiar Vallim, T.Q.; Wang, Z.; Shih, D.M.; Meng, Y.; Gregory, J.; Allayee, H.; Lee, R.; Graham, M.; Crooke, R.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, M.; Shih, D.M.; Burrows, A.C.; Ferguson, D.; Gromovsky, A.D.; Brown, A.L.; Marshall, S.; McDaniel, A.; Schugar, R.C.; Wang, Z.; et al. The TMAO-generating enzyme flavin monooxygenase 3 is a central regulator of cholesterol balance. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Buffa, J.A.; Wang, Z.; Warrier, M.; Schugar, R.; Shih, D.M.; Gupta, N.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Fu, X.; et al. Flavin monooxygenase 3, the host hepatic enzyme in the metaorganismal trimethylamine N-oxide-generating pathway, modulates platelet responsiveness and thrombosis risk. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 1857–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Roberts, A.B.; Buffa, J.A.; Levison, B.S.; Zhu, W.; Org, E.; Gu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zamanian-Daryoush, M.; Culley, M.K.; et al. Non-lethal inhibition of gut microbial trimethylamine production for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell 2015, 163, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthong, V.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L.; Tang, W.H. Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Mortality Risk in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e004237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthong, V.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.S.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tang, W.H.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal Microbiota-Generated Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and 5-Year Mortality Risk in Stable Coronary Artery Disease: The Contributory Role of Intestinal Microbiota in a COURAGE-Like Patient Cohort. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthong, V.; Li, X.S.; Hudec, T.; Coughlin, J.; Wu, Y.; Levison, B.; Wang, Z.; Hazen, S.L.; Tang, W.H. Plasma Trimethylamine N-Oxide, a Gut Microbe-Generated Phosphatidylcholine Metabolite, Is Associated With Atherosclerotic Burden. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 2620–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.S.; Obeid, S.; Klingenberg, R.; Gencer, B.; Mach, F.; Räber, L.; Windecker, S.; Rodondi, N.; Nanchen, D.; Muller, O.; et al. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide in acute coronary syndromes: A prognostic marker for incident cardiovascular events beyond traditional risk factors. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Kitai, T.; Hazen, S.L. Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Tan, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, P.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, R.; Chen, Y.; Song, L.; Zhao, H.; et al. Relation of Circulating Trimethylamine N-Oxide With Coronary Atherosclerotic Burden in Patients With ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 123, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Zhou, P.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Song, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Plasma Trimethylamine N-Oxide as a Novel Biomarker for Plaque Rupture in Patients With ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, e007281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, Z.; Tang, W.H.W.; Hazen, S.L. Gut microbe-generated trimethylamine N-oxide from dietary choline is prothrombotic in subjects. Circulation 2017, 135, 1671–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.B.; Gu, X.; Buffa, J.A.; Hurd, A.G.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Gupta, N.; Skye, S.M.; Cody, D.B.; Levison, B.S.; et al. Development of a gut microbe-targeted non-lethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential without enhanced bleeding. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skye, S.M.; Zhu, W.; Romano, K.A.; Guo, C.J.; Wang, Z.; Jia, X.; Kirsop, J.; Haag, B.; Lang, J.M.; DiDonato, J.A.; et al. Microbial Transplantation With Human Gut Commensals Containing CutC Is Sufficient to Transmit Enhanced Platelet Reactivity and Thrombosis Potential. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Levison, B.S.; Hazen, J.E.; Donahue, L.M.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Prognostic value of elevated levels of intestinal microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide in patients with heart failure: Refining the gut hypothesis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 1908–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Heaney, L.M.; Bhandari, S.S.; Jones, D.J.; Ng, L.L. Trimethylamine N-oxide and prognosis in acute heart failure. Heart 2016, 102, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, C.L.; Li, Z.; Sharp, T.E.; Polhemus, D.J.; Gupta, N.; Goodchild, T.T.; Tang, W.H.W.; Hazen, S.L.; Lefer, D.J. Nonlethal Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine N-oxide Production Improves Cardiac Function and Remodeling in a Murine Model of Heart Failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, X.S.; Wang, Z.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Fretts, A.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Budoff, M.; Nemet, I.; DiDonato, J.A.; et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide is associated with long-term mortality risk: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahenthiran, A.; Wilcox, J.; Tang, W.H.W. Heart Failure: A Punch from the Gut. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2024, 21, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.; Wang, Z.; Kennedy, D.J.; Wu, Y.; Buffa, J.A.; Agatisa-Boyle, B.; Li, X.S.; Levison, B.S.; Hazen, S.L. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Buffa, J.A.; Roberts, A.B.; Sangwan, N.; Skye, S.M.; Li, L.; Ho, K.J.; Varga, J.; DiDonato, J.A.; Tang, W.H.W.; et al. Targeted Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine N-Oxide Production Reduces Renal Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis and Functional Impairment in a Murine Model of Chronic Kidney Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 1239–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Miikeda, A.; Zuckerman, J.; Jia, X.; Charugundla, S.; Zhou, Z.; Kaczor-Urbanowicz, K.E.; Magyar, C.; Guo, F.; Wang, Z.; et al. Inhibition of microbiota-dependent TMAO production attenuates chronic kidney disease in mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, T.W.; Conrad, K.A.; Li, X.S.; Wang, Z.; Helsley, R.C.; Coughlin, T.M.; Wadding-Lee, C.; Fleifil, S.; Russell, H.M.; Stone, T.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Trimethylamine N-Oxide Contributes to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Through Inflammatory and Apoptotic Mechanisms. Circulation 2023, 147, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Romano, K.A.; Li, L.; Buffa, J.A.; Sangwan, N.; Prakash, P.; Tittle, A.N.; Li, X.S.; Fu, X.; Androjna, C.; et al. Gut microbes impact stroke severity via the trimethylamine N-oxide pathway. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1199–1208.e1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, R.N.; Jensen, P.N.; Wang, Z.; Fretts, A.M.; Sitlani, C.M.; Nemet, I.; Sotoodehnia, N.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Zhu, W.; Budoff, M.; et al. Plasma Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Incident Ischemic Stroke: The Cardiovascular Health Study and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e8711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schugar, R.C.; Shih, D.M.; Warrier, M.; Helsley, R.N.; Burrows, A.; Ferguson, D.; Brown, A.L.; Gromovsky, A.D.; Heine, M.; Chatterjee, A.; et al. The TMAO-Producing Enzyme Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 Regulates Obesity and the Beiging of White Adipose Tissue. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyridou, S.; Davies, M.J.; Biddle, G.J.H.; Bernieh, D.; Suzuki, T.; Dawkins, N.P.; Rowlands, A.V.; Khunti, K.; Smith, A.C.; Yates, T. Evaluation of an 8-Week Vegan Diet on Plasma Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Postchallenge Glucose in Adults with Dysglycemia or Obesity. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1844–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schugar, R.C.; Gliniak, C.M.; Osborn, L.J.; Massey, W.; Sangwan, N.; Horak, A.; Banerjee, R.; Orabi, D.; Helsley, R.N.; Brown, A.L.; et al. Gut microbe-targeted choline trimethylamine lyase inhibition improves obesity via rewiring of host circadian rhythms. eLife 2022, 11, e63998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnins, G.; Kuka, J.; Grinberga, S.; Makrecka-Kuka, M.; Liepinsh, E.; Dambrova, M.; Tars, K. Structure and Function of CutC Choline Lyase from Human Microbiota Bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 21732–21740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodea, S.; Funk, M.A.; Balskus, E.P.; Drennan, C.L. Molecular basis of C–N bond cleavage by the glycyl radical enzyme choline trimethylamine-lyase. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, S.H. A brief history of choline. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 61, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jameson, E.; Crosatti, M.; Schäfer, H.; Rajakumar, K.; Bugg, T.D.; Chen, Y. Carnitine metabolism to trimethylamine by an unusual Rieske-type oxygenase from human microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4268–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeth, R.A.; Lam-Galvez, B.R.; Kirso, P.J.; Wan, G.Z.; Levison, B.S.; Gu, X.; Copeland, M.F.; Bartlett, D.; Cody, D.B.; Dai, H.J.; et al. L-Carnitine in omnivorous diets induces an atherogenic gut microbial pathway in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffa, J.A.; Romano, K.A.; Copeland, M.F.; Cody, D.B.; Zhu, W.; Galvez, R.; Fu, X.; Ward, K.; Ferrell, M.; Dai, H.J.; et al. The microbial gbu gene cluster links cardiovascular disease risk associated with red meat consumption to microbiota L-carnitine catabolism. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.; Helsley, R.N.; Brown, A.L.; Buffa, J.A.; Choucair, I.; Nemet, I.; Gogonea, C.B.; Gogonea, V.; Wang, Z.; Garcia-Garcia, J.C.; et al. Small molecule inhibition of gut microbial choline trimethylamine lyase activity alters host cholesterol and bile acid metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H1474–H1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orman, M.; Bodea, S.; Funk, M.A.; Campo, A.M.; Bollenbach, M.; Drennan, C.L.; Balskus, E.P. Structure-guided identification of a small molecule that inhibits anaerobic choline metabolism by human gut bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, A.; Fritz-Wolf, K.; Kabsch, W.; Knappe, J.; Schultz, S.; Volker Wagner, A.F. Structure and mechanism of the glycyl radical enzyme pyruvate formate-lyase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999, 6, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Logan, D.T.; Andersson, J.; Sjöberg, B.M.; Nordlund, P. A glycyl radical site in the crystal structure of a class III ribonucleotide reductase. Science 1999, 283, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynaud, C.; Sarçabal, P.; Meynial-Salles, I.; Croux, C.; Soucaille, P. Molecular characterization of the 1,3-propanediol (1,3-PD) operon of Clostridium butyricum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5010–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, B.J.; Huang, Y.Y.; Peck, S.C.; Wei, Y.; Martínez-Del Campo, A.; Marks, J.A.; Franzosa, E.A.; Huttenhower, C.; Balskus, E.P. A prominent glycyl radical enzyme in human gut microbiomes metabolizes trans-4-hydroxy-l-proline. Science 2017, 355, eaai8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, S.C.; Denger, K.; Burrichter, A.; Irwin, S.M.; Balskus, E.P.; Schleheck, D. A glycyl radical enzyme enables hydrogen sulfide production by the human intestinal bacterium Bilophila wadsworthia. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3171–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuthner, B.; Leutwein, C.; Schulz, H.; Hörth, P.; Haehnel, W.; Schiltz, E.; Schägger, H.; Heider, J. Biochemical and genetic characterization of benzylsuccinate synthase from Thauera aromatica: A new glycyl radical enzyme catalysing the first step in anaerobic toluene metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 28, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Mehmood, R.; Wang, M.; Qi, H.W.; Steeves, A.H.; Kulik, H.J. Revealing quantum mechanical effects in enzyme catalysis with large-scale electronic structure simulation. React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Q.; Deng, W.H.; Liao, R.Z. Mechanistic Insights into Choline Degradation Catalyzed by the Choline Trimethylamine-Lyase CutC. J. Phys. Chem. B 2025, 129, 5438–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzevacki, M.; Güven, J.J.; Hinchliffe, P.; Shaw, J.; Mey, A.S.J.S.; Fey, N.; Spencer, J.; Mulholland, A.J. All Roads Lead to Carbinolamine: QM/MM Study of Enzymatic C-N Bond Cleavage in Anaerobic Glycyl Radical Enzyme Choline Trimethylamine-Lyase (CutC). J. Phys. Chem. B 2025, 129, 9322–9332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, H.R. Anaerobic degradation of choline. III. Acetaldehyde as an intermediate in the fermentation of choline by extracts of Vibrio cholinicus. J. Biol. Chem. 1960, 235, 3592–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsin, D.A. Ethanolamine utilization in bacterial pathogens: Roles and regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeaux, C.J.; van der Donk, W.A. Converging on a Mechanism for Choline Degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21184–21185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovačević, B.; Barić, D.; Babić, D.; Bilić, L.; Hanževački, M.; Sandala, G.M.; Radom, L.; Smith, D.M. Computational Tale of Two Enzymes: Glycerol Dehydration with or without B12. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8487–8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Ostlung, N.S. Modern Quantum Chemistry; MacMillan Publishing Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield, R.; Hehre, W.J.; Pople, J.A. Self-Consistent Molecular-Orbital Methods. IX. An Extended Gaussian-Type Basis for Molecular-Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Density-Functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian-basis sets for atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Huber, C.; Ahlrichs, R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian-basis sets of triple zeta valence quality for atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 100, 5829–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.H.; Søndergaard, C.R.; Rostkowski, M.; Jensen, J.H. PROPKA3: Consistent treatment of internal and surface residues in empirical pKa predictions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, J.C.; Myers, J.B.; Folta, T.; Shoja, V.; Heath, L.S.; Onufriev, A. H++: A server for estimating pKas and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W368–W371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornak, V.; Abel, R.; Okur, A.; Strockbine, B.; Roitberg, A.; Simmerling, C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins 2006, 65, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, L.W.; Sameera, W.M.; Ramozzi, R.; Page, A.J.; Hatanaka, M.; Petrova, G.P.; Harris, T.V.; Li, X.; Ke, Z.; Liu, F.; et al. The ONIOM Method and Its Applications. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 5678–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, W.D.; Cieplak, P.; Bayly, C.I.; Gould, I.R.; Merz, K.M.J.; Ferguson, D.M.; Spellmeyer, D.C.; Fox, T.; Caldwell, J.W.; Kollman, P.A. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5179–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W.; Baldridge, K.K.; Boatz, J.A.; Elbert, S.T.; Gordon, M.S.; Jensen, J.H.; Koseki, S.; Matsunaga, N.; Nguyen, K.A.; Su, S.; et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14, 1347–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, H.; Cavallo, L. Directions for Use of Density Functional Theory: A Short Instruction Manual for Chemists. In Handbook of Computational Chemistry; Leszczynski, J., Kaczmarek-Kedziera, A., Puzyn, T.G., Papadopoulos, M., Reis, H.K., Shukla, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mardirossiana, N.; Head-Gordon, M. Thirty years of density functional theory in computational chemistry: An overview and extensive assessment of 200 density functionals. Mol. Phys. 2017, 115, 2315–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogojeski, M.; Vogt-Maranto, L.; Tuckerman, M.E.; Müller, K.R.; Burke, K. Quantum chemical accuracy from density functional approximations via machine learning. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; Bowling, P.E.; Herbert, J.M. Comment on “Benchmarking Basis Sets for Density Functional Theory Thermochemistry Calculations: Why Unpolarized Basis Sets and the Polarized 6-311G Family Should Be Avoided”. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 7739–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, S.J.; Evans, A.K.; Ireland, R.T.; Lempriere, F.; McKemmish, L.K. Reply to Comment on “Benchmarking Basis Sets for Density Functional Theory Thermochemistry Calculations: Why Unpolarized Basis Sets and the Polarized 6-311G Family Should Be Avoided”. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 7733–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warshel, A.; Bora, R. Perspective: Defining and quantifying the role of dynamics in enzyme catalysis. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 180901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrdanz, M.A.; Martins, K.M.; Herbert, J.M. A Long-Range-Corrected Density Functional That Performs Well for Both Ground-State Properties and Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory Excitation Energies, Including Charge-Transfer Excited States. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 054112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harihara, P.C.; Pople, J.A. Influence of Polarization Functions on Molecular-Orbital Hydrogenation Energies. Theor. Chim. Acta 1973, 28, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufimtsev, I.S.; Martinez, T.J. Quantum Chemistry on Graphical Processing Units. 3. Analytical Energy Gradients, Geometry Optimization, and First Principles Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K.E.; Simmerling, C. ff14SB: Improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroff, G.P.; Fessenden, R.W. Equilibrium and Kinetics of the Acid Dissociation of Several Hydroxyalkyl Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1973, 77, 3–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Forester, T.R. DL_POLY_2.0: A general-purpose parallel molecular dynamics simulation package. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riplinger, C.; Neese, F. An Efficient and Near Linear Scaling Pair Natural Orbital Based Local Coupled Cluster Method. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 034106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, W.H.; Buffa, J.A.; Fu, X.; Britt, E.B.; Koeth, R.A.; Levison, B.S.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Prognostic value of choline and betaine depends on intestinal microbiota-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pair of Atoms | Distance [Å] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vacuum | QM/MM | ||

| Without MM Charges | with MM Charges | ||

| Reactant | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.012 | 1.037 | 1.006 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.573 | 1.473 | 1.584 |

| Chol-C1…N | 2.582 | 2.560 | 2.555 |

| Chol-C2…N | 1.506 | 1.507 | 1.508 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 1.104 | 1.116 | 1.115 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 2.174 | 2.096 | 2.102 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 3.780 | 2.468 | 2.453 |

| Transition state 1 (TS1) | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.396 | 1.420 | 1.055 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.064 | 1.053 | 1.419 |

| Chol-C1…N | 2.559 | 2.560 | 2.538 |

| Chol-C2…N | 1.514 | 1.525 | 1.524 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 1.393 | 1.369 | 1.459 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 2.161 | 2.214 | 2.312 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 1.597 | 1.643 | 1.559 |

| Intermediate 1 (I1) | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.419 | 1.421 | 1.049 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.054 | 1.059 | 1.436 |

| Chol-C1…N | 2.581 | 2.590 | 2.535 |

| Chol-C2…N | 1.573 | 1.599 | 1.542 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 2.685 | 2.336 | 2.283 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 3.232 | 2.904 | 2.941 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 1.366 | 1.360 | 1.360 |

| Transition state 2 (TS2) | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.534 | 1.503 | 1.053 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.020 | 1.032 | 1.413 |

| Chol-C1…N | 2.172 | 2.748 | 2.824 |

| Chol-C2…N | 2.720 | 1.876 | 2.751 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 2.859 | 2.658 | 2.560 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 3.056 | 2.956 | 2.281 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 1.355 | 1.350 | 1.354 |

| Intermediate 2 (I2) | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.527 | 1.546 | 1.047 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.026 | 1.016 | 1.425 |

| Chol-C1…N | 2.958 | 2.906 | 2.876 |

| Chol-C2…N | 2.116 | 2.268 | 2.819 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 2.780 | 2.725 | 2.535 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 3.020 | 2.741 | 2.263 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 1.349 | 1.350 | 1.354 |

| Transition state 2’ (TS2’) | |||

| Chol-O…H | - | - | 1.347 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | - | - | 1.085 |

| Chol-C1…N | - | - | 2.101 |

| Chol-C2…N | - | - | 2.700 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | - | - | 2.709 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | - | - | 2.158 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | - | - | 1.354 |

| Intermediate 2’ (I2’) | |||

| Chol-O…H | - | - | 1.031 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | - | - | 1.490 |

| Chol-C1…N | - | - | 1.597 |

| Chol-C2…N | - | - | 2.523 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | - | - | 2.822 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | - | - | 2.205 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | - | -- | 1.353 |

| Transition state 3 (TS3) | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.605 | 1.570 | 1.042 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.008 | 1.004 | 1.445 |

| Chol-C1…N | 2.485 | 2.432 | 1.600 |

| Chol-C2…N | 2.724 | 2.887 | 2.555 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 2.292 | 2.300 | 2.418 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 1.462 | 1.490 | 1.549 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 1.516 | 1.495 | 1.474 |

| Intermediate 3 (I3) | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.022 | 1.418 | 1.018 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 3.047 | 1.057 | 1.540 |

| Chol-C1…N | 1.568 | 1.731 | 1.576 |

| Chol-C2…N | 2.567 | 2.600 | 2.544 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 2.109 | 2.130 | 2.116 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 1.099 | 1.099 | 1.097 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 4.720 | 2.511 | 2.565 |

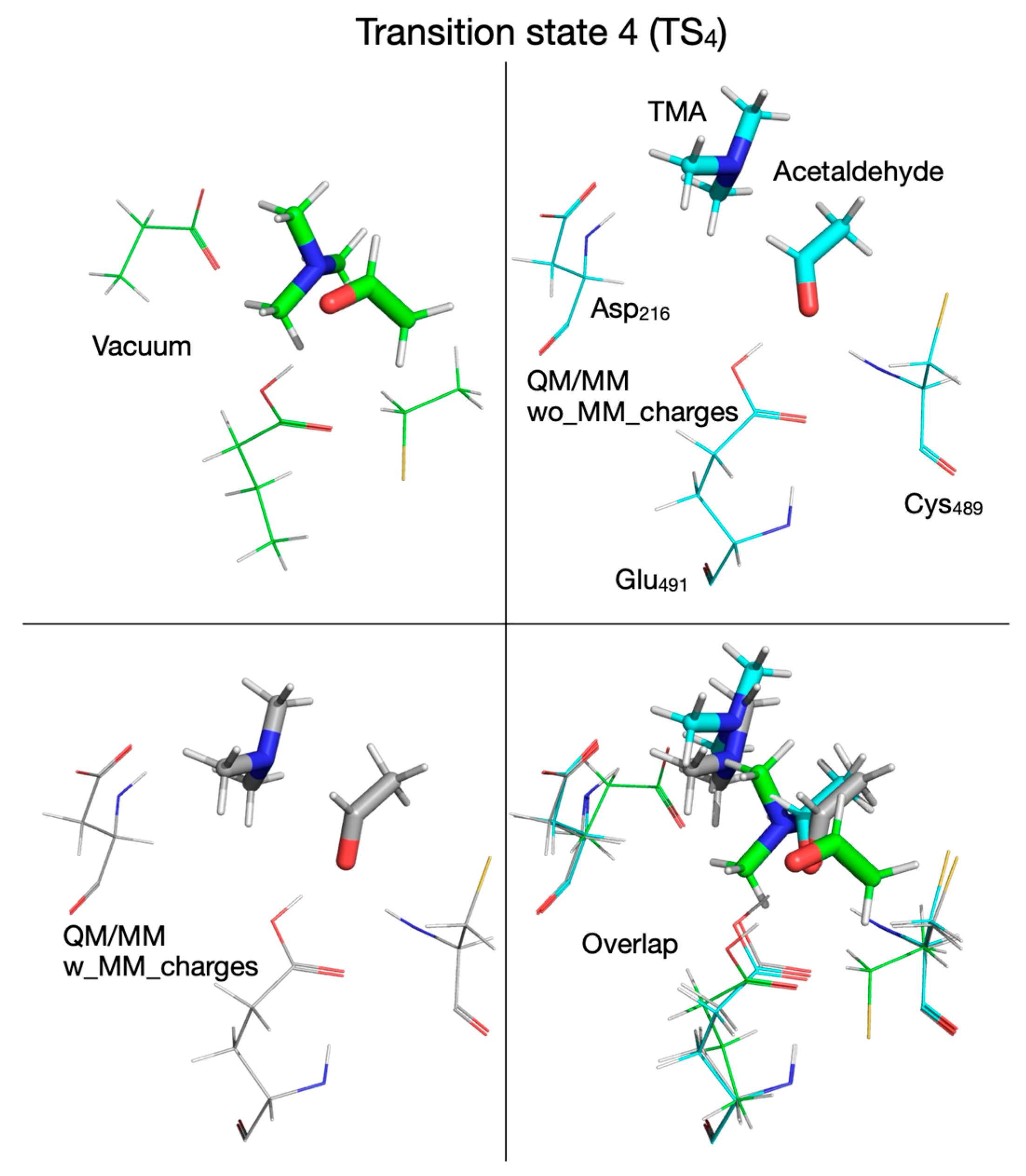

| Transition state 4 (TS4) | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.736 | 1.652 | 1.554 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 0.989 | 0.995 | 1.012 |

| Chol-C1…N | 3.141 | 3.130 | 2.901 |

| Chol-C2…N | 3.224 | 3.234 | 3.329 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 2.140 | 2.115 | 2.103 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 1.100 | 1.099 | 1.097 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 5.677 | 3.294 | 4.343 |

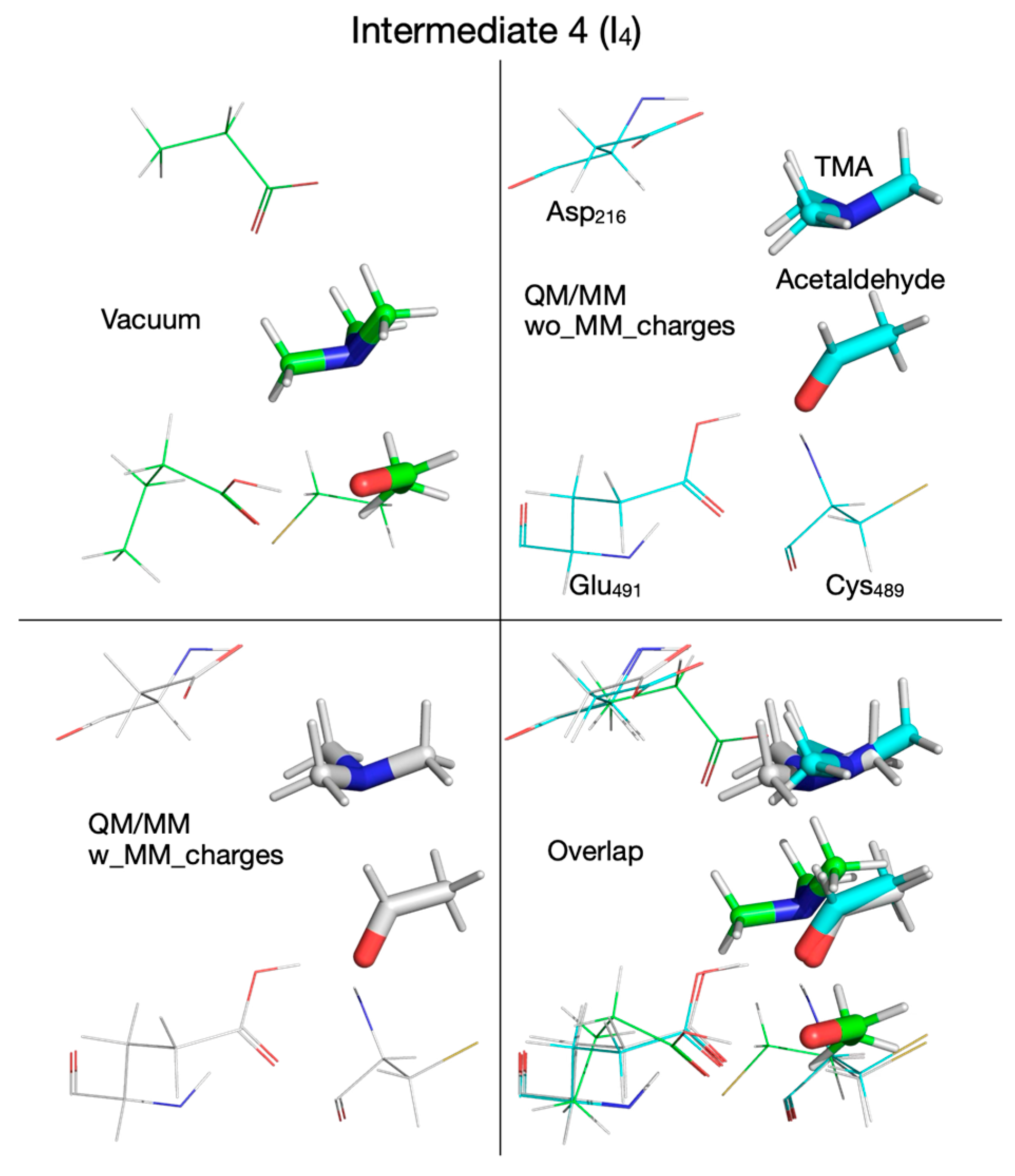

| Intermediate 4 (I4) | |||

| Chol-O…H | 1.175 | 1.649 | 1.558 |

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 0.990 | 0.995 | 1.014 |

| Chol-C1…N | 3.698 | 3.150 | 2.997 |

| Chol-C2…N | 3.120 | 3.211 | 3.487 |

| Chol-C1…H11 | 2.135 | 3.126 | 2.158 |

| Chol-C2…H11 | 1.100 | 1.098 | 1.097 |

| Chol-H11…S-Cys489 | 5.463 | 3.894 | 2.643 |

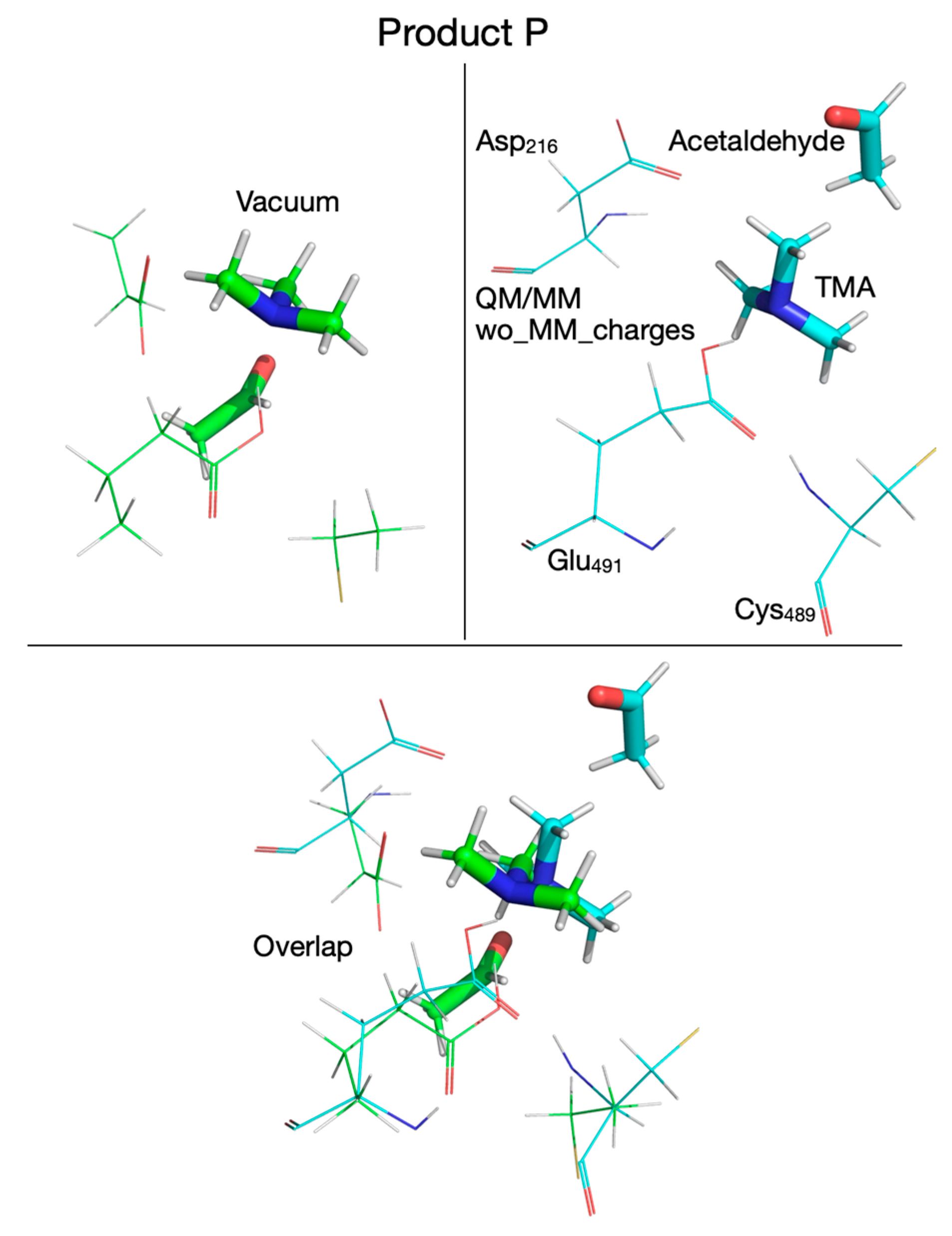

| Product P | |||

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.017 | 1.029 | - |

| Chol-OH…OD-Asp216 | 3.255 | 4.735 | - |

| Chol-OH…N | 1.673 | 1.696 | - |

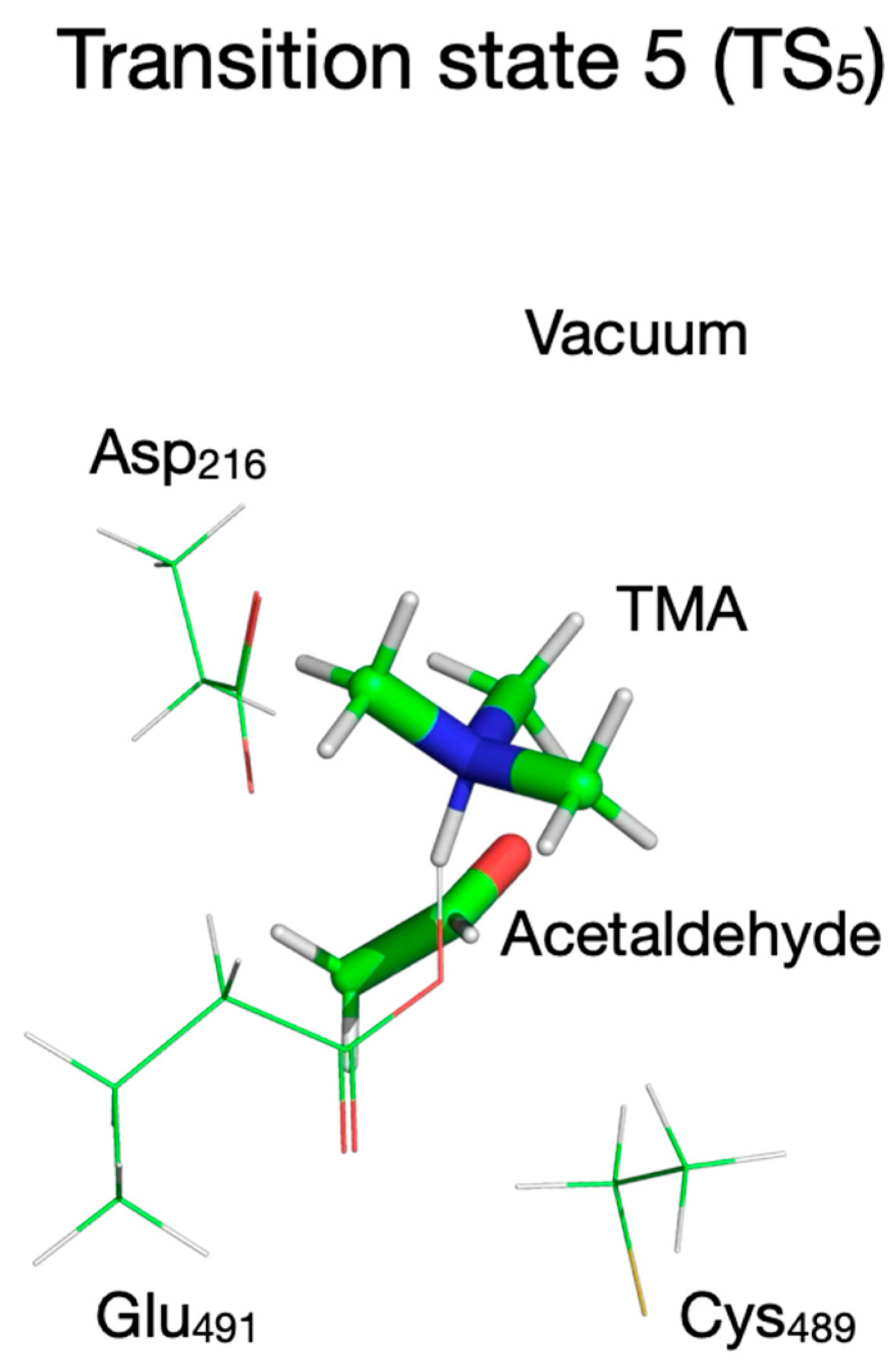

| Transition state 5 (TS5) | |||

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.343 | - | - |

| Chol-OH…OD-Asp216 | 2.976 | - | - |

| Chol-OH…N | 1.172 | - | - |

| Product P3 | |||

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 1.542 | 1.444 | - |

| Chol-OH…OD-Asp216 | 2.665 | 4.215 | - |

| Chol-OH…N | 1.089 | 1.129 | - |

| Product P2 | |||

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 3.500 | 4.660 | 4.702 |

| Chol-OH…OD-Asp216 | 1.050 | 1.011 | 1.011 |

| Chol-OH…N | 1.556 | 1.771 | 1.603 |

| Product P3’ | |||

| Chol-OH…OE-Glu491 | 3.278 | 4.034 | 4.032 |

| Chol-OH…OD-Asp216 | 1.546 | 1.535 | 1.637 |

| Chol-OH…N | 1.051 | 1.069 | 1.060 |

| Chemical Species | Vacuum | QM/MM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without MM Charges | with MM Charges | |||||

| Energy a | Vib Freq b | Energy | Vib Freq | Energy | Vib Freq | |

| Reactant | 0 | 11.9 | 0 | 30.7 | 0 | 28.5 |

| TS1 | 8.5 | 737.7i | 6.2 | 773.5i | 9.6 | 1073.9i |

| I1 | 2.7 | 11.4 | 3.5 | 32.5 | 2.6 | 22.8 |

| TS2 | 12.4 | 130.7i | 5.8 | - | 12.1 | - |

| I2 | 6.8 | 9.0 | 5.2 | 32.8 | 11.9 | 34.2 |

| TS2’ | - | - | - | - | 15.9 | 152.3i |

| I2’ | - | - | - | - | 8.3 | 32.0 |

| TS3 | 20.7 | 1197.8i | 16.2 | 1265.8i | 18.2 | 1039.6i |

| I3 | −9.2 | 10.6 | −5.6 | 33.6 | −4.6 | 34.8 |

| TS4 | 8.1 | 97.8i | 4.5 | - | 20.0 | 24.5i |

| I4 | 5.9 | 8.1 | 4.1 | 31.0 | 19.6 | 33.1 |

| P | −8.9 | 6.2 | 8.6 | 30.5 | 11.8 | - |

| TS5 | −5.2 | 77.1i | 8.6 | - | 11.80 | - |

| P3 | −5.3 | 9.7 | 7.6 | 30.2 | 3.7 | - |

| P2 | −13.5 | 9.5 | 7.3 | 28.4 | 13.7 | - |

| P3’ | −10.8 | - | 11.1 | - | 5.1 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gogonea, V.; Hazen, S.L. Steric and Electronic Effects in the Enzymatic Catalysis of Choline-TMA Lyase. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010037

Gogonea V, Hazen SL. Steric and Electronic Effects in the Enzymatic Catalysis of Choline-TMA Lyase. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleGogonea, Valentin, and Stanley L. Hazen. 2026. "Steric and Electronic Effects in the Enzymatic Catalysis of Choline-TMA Lyase" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010037

APA StyleGogonea, V., & Hazen, S. L. (2026). Steric and Electronic Effects in the Enzymatic Catalysis of Choline-TMA Lyase. Biomolecules, 16(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010037