Signaling Pathways of the Acquired Immune System and Myocardial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease—What Do We Know So Far?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Alterations in the Cellular Components of the Acquired Immune System in CKD

2.1. T Lymphocytes

2.2. T Regulatory Cells

2.3. B Lymphocytes

3. The Implication of Cells of the Acquired Immune System in the Pathogenesis of Myocardial Dysfunction in CKD

3.1. T Cells

| Author/Year | Subjects | Immune Cell Subset | Findings | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winterberg et al., 2019 [76] | Mice; humans—pediatric patients with CKD | T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells | Mice Early infiltration of T cells in the myocardium following CKD development; improvements in diastolic function in mice following T cell depletion with anti-CD3 antibody. Pediatric CKD patients PD-1 and/or CD57 + T cells associated with increased E/E’ in pediatric CKD patients; CCR7−CD45RA+ CD4+ T cells associated with improved diastolic function in pediatric CKD patients; loss of naïve CD4+ or CD8+ T cells associated with LVH; reduced CD4:CD8 ratio associated with impaired diastolic function in pediatric patients with CKD. | Accumulation of central (CD44hiCD62L+) and effector (CD44hiCD62L−) memory CD4+ T cells in spleen and peripheral blood of CKD mice; increased expression of KLRG1, PD-1 and/or OX-40 activation markers in CD4+ T cells of CKD mice. Limitations: small sample size. |

| Han et al., 2023 [77] | Mice; humans—patients with stages 3 to 5 CKD and healthy controls | T cells, CD4+ T cells | Augmented myocardial infiltration of CD4+ T cells in mice transplanted with gut microbiota from CKD patients; significant increase in cardiac IFNγ+ CD4+ T cell infiltration in CKD microbiota recipient mice compared to healthy controls; significantly increased cardiac IFNγ+ CD4+ T cell infiltration associated with more severe diastolic dysfunction in mice administered K. pneumoniae compared to control mice. | Abnormal immune responses induced by aberrant gut microbiome in CKD—a potential link in the gut microbiota–gut–kidney–heart axis; pathways involved in IFNγ+ CD4+ T cell migration from gut to cardiac tissue in uremic cardiomyopathy unclear. |

| Duni et al., 2024 [78] | Humans—CKD patients, KTRs without established CVD and healthy controls | T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Tregs | Negative correlation of CD4+ T cells with LVEF in CKD patients and with dipyridamole-induced improvement of LVEF in KTRs; CD4+ T cells inversely correlated with dipyridamole-induced improvements in GLS in KTRs; independent association of CD8+ T cells with improved left ventricular twist and untwist in CKD patients. | Observational study, cross-sectional design; small sample size; expression of immune cell subsets examined in the peripheral blood but not in cardiac tissue. |

| Duni et al., 2023 [90] | Humans—patients with type 2 CRS and CKD patients without CVD as control subjects | T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Tregs | In Kaplan–Meier analysis, decreased lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and Tregs associated with mortality at a median follow-up of 30 months (p < 0.05 for all log-rank tests) in type 2 CRS patients. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, only the CD4+ T lymphocytes were independent predictors of mortality (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.50–0.87; p = 0.004) in type 2 CRS patients. | Inverse association between the CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio with proteinuria in CRS-2 patients; decreased Treg levels in patients with CRS-2 vs. CKD patients without CVD; decreased Treg levels in patients with CRS-2 and AF vs. those without AF. |

| Zhang et al., 2010 [36] | Humans—hemodialysis patients, patients with advanced CKD and healthy subjects as controls | Th17 cells, Tregs | Increased Th17-to-Treg ratio in hemodialysis patients with NYHA III–IV heart failure vs. the NYHA I–II group (3.0:1.9 vs. 1.7:3.2; p < 0.01). | Increased serum CRP and IL-6 levels positively correlated with the increased Th17 cells and decreased Tregs. |

| Vernier et al., 2024 [91] | Mice | T lymphocytes, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, B lymphocytes | In type 3 CRS, CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell populations in the kidney mediated renal inflammation and the repair phase of IRI; only B lymphocytes mediated cardiac injury. Significant increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the kidneys 15 days after IRI; no differences in cardiac Cd4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in cardiac tissue post IRI; B lymphocytes declined in both kidney and cardiac tissue in the setting of renal IRI. | Kidney tissue repair response characterized by Foxp3 activation; cardiac tissue inflammation mediated by IL-17RA and IL-1β. |

| Lin et al., 2022 [92] | Humans—patients with stage 4 and 5 CKD and non-CKD (controls) | CD19+ B cells, CD19+CD5+ B cells, CD19+CD5- B cells | Negative correlation of CD19+CD5+ B cells with LVDD, LVSD and LVM; LVEF positively correlated with CD19+ CD5+ B and CD19+CD5− B cells; CD19+CD5+ B cells ≤ 0.03 × 109/L associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 2.967, 95%CI: 1.067–8.254, p = 0.037). | Retrospective study; cohort of elderly patients; unclarified mechanisms of B cell implications in myocardial remodeling in CKD patients. |

| Yang et al., 2023 [93] | Humans—kidney failure | CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD19+ B cells | Decreased CD3+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and B cells in patients with LVH. | |

| Molina et al., 2018 [94] | Humans—hemodialysis patients | CD3+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD19+ B cells | CD19+ B cell count < 100 cells/μL at baseline and after 1 year associated with all-cause mortality (HR 2, 95% CI: 1.05–3.8, p = 0.03 and HR 3.8, 95% CI: 1.005–14, p = 0.04, respectively); CD19+ B cell count < 100 cells/μL at baseline associated with CV mortality (HR 4.1, IC 95%: 1.2–14.6, p = 0.02). | Prospective observational single-center study; peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets. |

| Duni et al., 2021 [95] | Humans—PD patients and healthy controls | T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Tregs | Inverse association of the total lymphocyte count and percentage of B cells with overhydration; the percentage of B cells was inversely associated with the presence of CAD. | Small sample size; observational and cross-sectional study; peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets. |

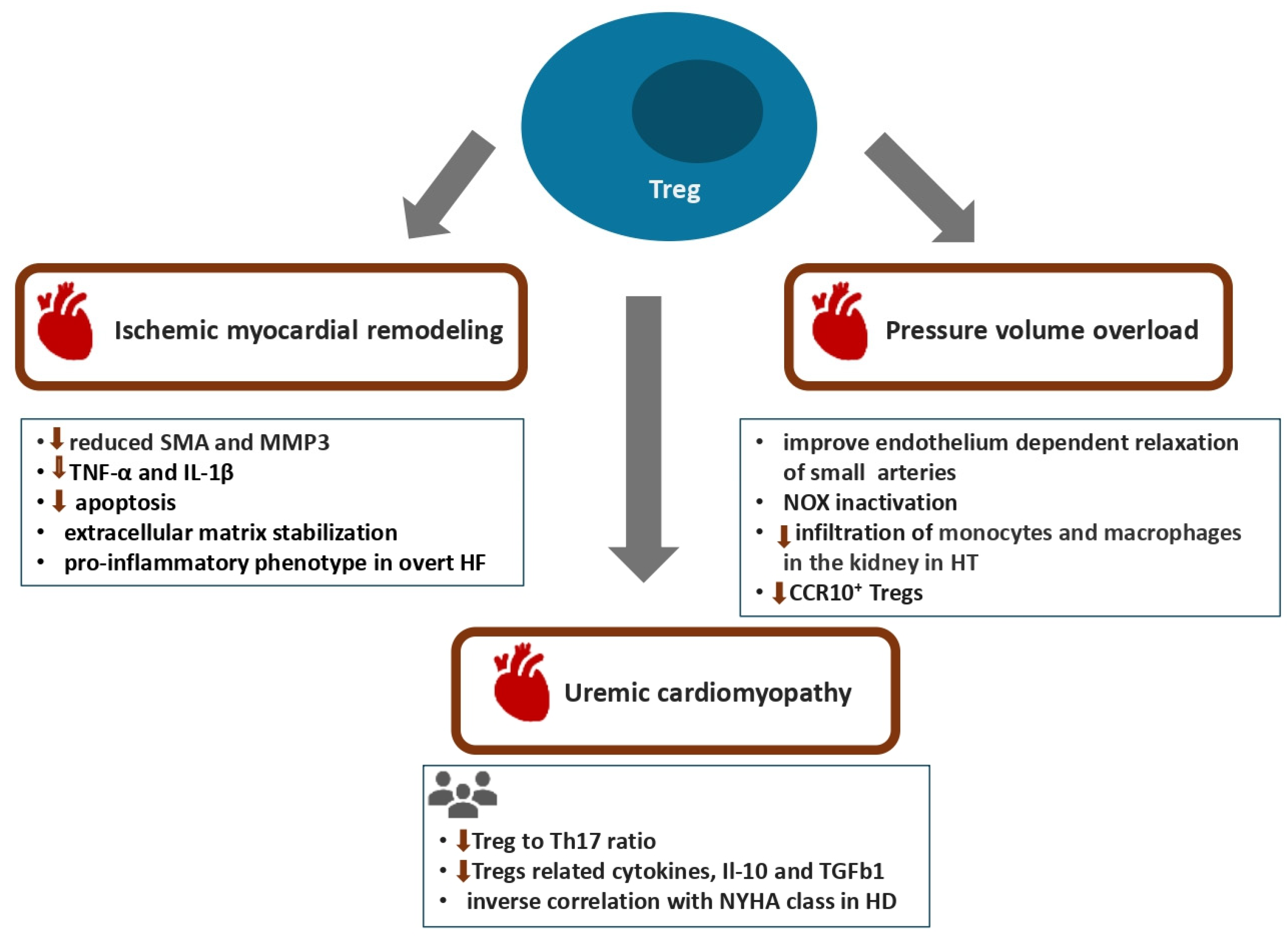

3.2. T Regulatory Cells

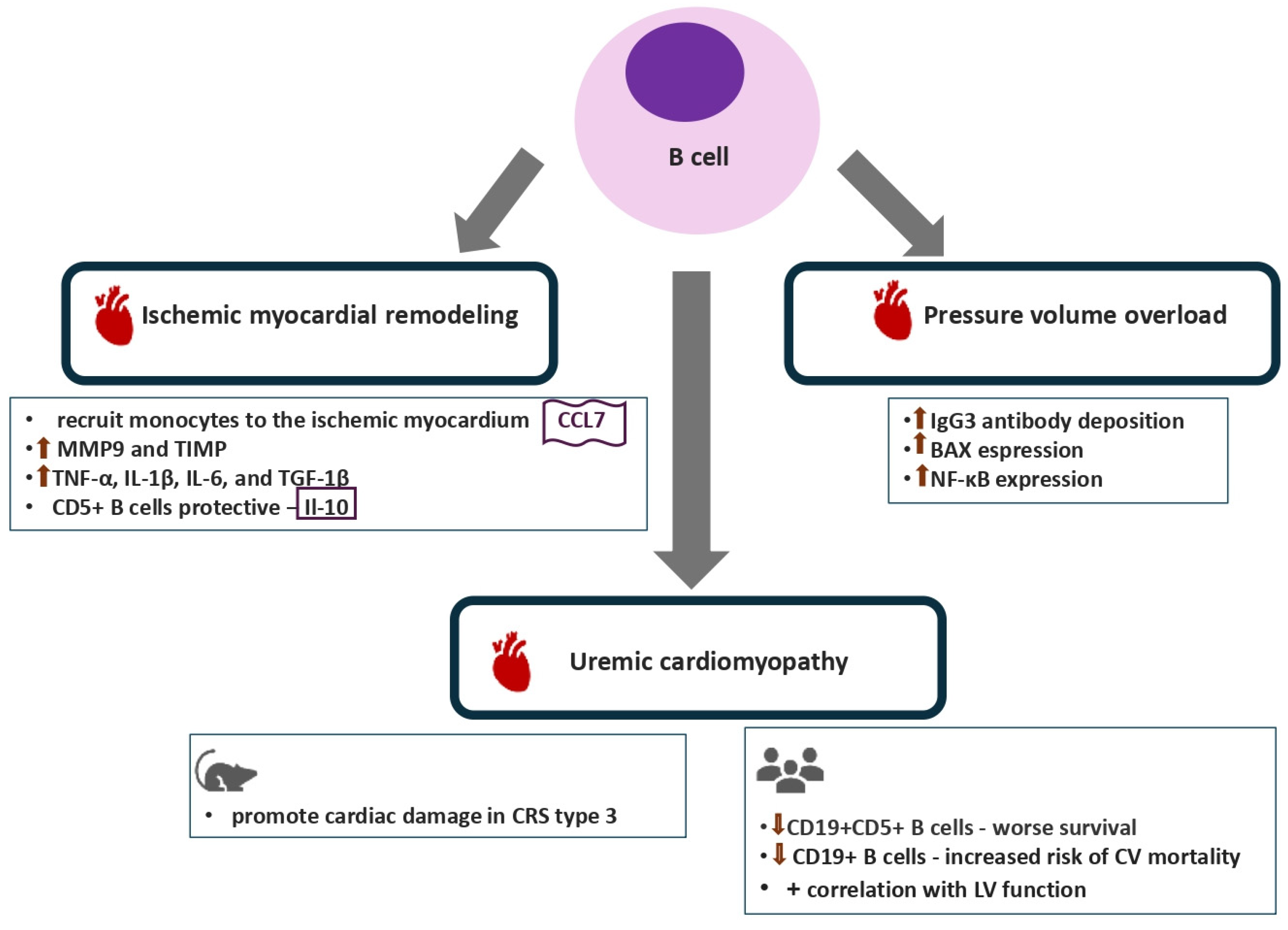

3.3. B Lymphocytes

4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zoccali, C. Traditional and emerging cardiovascular and renal risk factors: An epidemiologic perspective. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Mitra, N.; Kanetsky, P.A.; Devaney, J.; Wing, M.R.; Reilly, M.; Shah, V.O.; Balakrishnan, V.S.; Guzman, N.J.; Girndt, M.; et al. CRIC Study Investigators. Association between albuminuria, kidney function, and inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P.; Mallat, Z.; Weyand, C. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms mediate cardiovascular diseases from head to toe. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 2503–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, M.; Coppolino, G.; De Nicola, L.; Serra, R.; Garofalo, C.; Andreucci, M.; Bolignano, D. Unraveling Cardiovascular Risk in Renal Patients: A New Take on Old Tale. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Hsu, C.; Li, Y.; Mishra, R.K.; Keane, M.; Rosas, S.E.; Dries, D.; Xie, D.; Chen, J.; He, J.; et al. Associations between kidney function and subclinical cardiac abnormalities in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1725–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, C.; McCullough, P.; Anker, S.D.; Anand, I.; Aspromonte, N.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Bellomo, R.; Berl, T.; Bobek, I.; Cruz, D.N.; et al. Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) consensus group. Cardio-renal syndromes: Report from the consensus conference of the acute dialysis quality initiative. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, A.; Chatterjee, K.; Mathew, R.O.; Sidhu, M.S.; Bangalore, S.; McCullough, P.A.; Rangaswami, J. In-hospital mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events after kidney transplantation in the United States. Cardiorenal Med. 2019, 9, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dounousi, E.; Duni, A.; Naka, K.K.; Vartholomatos, G.; Zoccali, C. The Innate Immune System and Cardiovascular Disease in ESKD: Monocytes and Natural Killer Cells. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2021, 19, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Glynn, R.J.; Koenig, W.; Libby, P.; Everett, B.M.; Lefkowitz, M.; Thuren, T.; Cornel, J.H. Inhibition of Interleukin-1β by Canakinumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2405–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, G.M.; Chang, A.M.; Felker, G.M.; Heise, M.; Velkoska, E.; Fellström, B.; Charytan, D.M.; Clementi, R.; Gibson, C.M.; Goodman, S.G.; et al. IL-6 inhibition with clazakizumab in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: A randomized phase 2b trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2328–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.X.; Aetesam-Ur-Rahman, M.; Sage, A.P.; Victor, S.; Kurian, R.; Fielding, S.; Ait-Oufella, H.; Chiu, Y.D.; Binder, C.J.; Mckie, M.; et al. Rituximab in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: An experimental medicine safety study. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.W.; Gollapudi, S.; Pahl, M.V.; Vaziri, N.D. Naive and central memory T-cell lymphopenia in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descamps-Latscha, B.; Chatenoud, L. T cells and B cells in chronic renal failure. Semin. Nephrol. 1996, 16, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Winterberg, P.D.; Ford, M.L. The effect of chronic kidney disease on T cell alloimmunity. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2017, 22, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betjes, M.G.N. Immune cell dysfunction and inflammation in end-stage renal disease. Rev. Nephrol. 2013, 9, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, T.; Antoniadi, G.; Liakopoulos, V.; Kartsios, C.; Stefanidis, I. Disturbances of acquired immunity in hemodialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2007, 20, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betjes, M.G.; Langerak, A.W.; van der Spek, A.; de Wit, E.A.; Litjens, N.H. Premature aging of circulating T cells in patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, P.; Dayer, E.; Blanc, E.; Wauters, J.P. Early T cell activation correlates with expression of apoptosis markers in patients with end-stage renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litjens, N.H.; van Druningen, C.J.; Betjes, M.G. Progressive loss of renal function is associated with activation and depletion of naive T lymphocytes. Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girndt, M.; Köhler, H.; Schiedhelm-Weick, E.; zum Büschenfelde, K.H.M.; Fleischer, B. T cell activation defect in hemodialysis patients: Evidence for a role of theB7⁄CD28 pathway. Kidney Int. 1993, 44, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girndt, M.; Sester, M.; Sester, U.; Kaul, H. Defective expression of B7-2 (CD86) on monocytes of dialysis patients correlates to the uremiaassociated immune defect. Kidney Int. 2001, 59, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzell, S.; Bin, S.; Cantarelli, C.; Haverly, M.; Manrique, J.; Angeletti, A.; Manna, G.; Murphy, B.; Zhang, W.; Levitsky, J.; et al. Kidney Failure Associates with T Cell Exhaustion and Imbalanced Follicular Helper T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Jha, V. CD4+ CD28null cells are expanded and exhibit a cytolytic profile in end-stage renal disease patients on peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 1689–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, R.W.; Litjens, N.H.; de Wit, E.A.; Langerak, A.W.; Baan, C.C.; Betjes, M.G. Uremia-associated immunological aging is stably imprinted in the T-cell system and not reversed by kidney transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2014, 27, 1272–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, Y.; Jamme, M.; Rabant, M.; DeWolf, S.; Noel, L.H.; Thervet, E.; Chatenoud, L.; Snanoudj, R.; Anglicheau, D.; Legendre, C.; et al. Long-term CD4 lymphopenia is associated with accelerated decline of kidney allograft function. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.P.; Mehta, A.K.; Perez, S.D.; Winterberg, P.; Cheeseman, J.; Johnson, B.; Kwun, J.; Monday, S.; Stempora, L.; Warshaw, B.; et al. Premature T Cell Senescence in Pediatric CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 28, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagiotas, L.; Lioulios, G.; Panteli, M.; Ouranos, K.; Xochelli, A.; Kasimatis, E.; Nikolaidou, V.; Samali, M.; Daoudaki, M.; Katsanos, G. Kidney Transplantation and Cellular Immunity Dynamics: Immune Cell Alterations and Association with Clinical and Laboratory Parameters. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhard, J.; Schaier, M.; Kälble, F.; Eckstein, V.; Zeier, M.; Steinborn, A. Chronic Kidney Failure Provokes the Enrichment of Terminally Differentiated CD8+ T Cells, Impairing Cytotoxic Mechanisms After Kidney Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 752570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemont, L.; Tilly, G.; Yap, M.; Doan-Ngoc, T.M.; Danger, R.; Guérif, P.; Delbos, F.; Martinet, B.; Giral, M.; Foucher, Y.; et al. Terminally Differentiated Effector Memory CD8+ T Cells Identify Kidney Transplant Recipients at High Risk of Graft Failure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 876–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laecke, S.; Glorieux, G. Terminally differentiated effector memory T cells in kidney transplant recipients: New crossroads. Am. J. Transplant. 2025, 25, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, N.; Sakaguchi, S. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune kidney diseases and transplantation. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, D.; Wang, Y.; Qin, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, G.; Wang, Y.M.; Alexander, S.I.; Harris, D.C. CD4þCD25þ regulatory T cells protect against injury in an innate murine model of chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, G.Y.; Saito, M.; Wang, Y.M.; Fernandez, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Hawthorne, W.J.; Jones, C.; et al. Infiltrating Foxp3þ regulatory T cells from spontaneously tolerant kidney allografts demonstrate donorspecific tolerance. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13, 2819–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrikx, T.K.; van Gurp, E.A.; Mol, W.M.; Schoordijk, W.; Sewgobind, V.D.; IJzermans, J.N.; Weimar, W.; Baan, C.C. End-stage renal failure and regulatory activities of CD4+ CD25bright+ FoxP3+ T-cells. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, L.; Nopp, A.; Jacobson, S.H.; Hylander, B.; Lundahl, J. Hemodialysis Patients Display a Declined Proportion of Th2 and Regulatory T Cells in Parallel with a High Interferon-gamma Profile. Nephron 2017, 136, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hua, G.; Zhang, X.; Tong, R.; Du, X.; Li, Z. Regulatory T cells/T-helper cell 17 functional imbalance in uraemic patients on maintenance haemodialysis: A pivotal link between microinflammation and adverse cardiovascular events. Nephrology 2010, 15, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettelli, E.; Carrier, Y.; Gao, W.; Korn, T.; Strom, T.B.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L.; Kuchroo, V.K. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 2006, 441, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Kitani, A.; Fuss, I.; Strober, W. Cutting edge: Regulatory T cells induce CD4+ CD25- Foxp3- T cells or are self-induced to become Th17 cells in the absence of exogenous TGF-beta. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 6725–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, N.H.; Boer, K.; Zuijderwijk, J.M.; Klepper, M.; Peeters, A.M.; Verschoor, W.; Kraaijeveld, R.; Betjes, M.G. Natural regulatory T cells from patients with end-stage renal disease can be used for large-scale generation of highly suppressive alloantigen-specific Tregs. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, C.; Kinsey, G.R.; Corradi, V.; Xin, W.; Ma, J.Z.; Scalzotto, E.; Martino, F.K.; Okusa, M.D.; Nalesso, F.; Ferrari, F.; et al. The Influence of Hemodialysis on T Regulatory Cells: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Blood Purif. 2016, 42, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, C.; Corradi, V.; Scalzotto, E.; Frigo, A.C.; Proglio, M.; Sharma, R.; Ronco, C. Differential effects of peritoneal and hemodialysis on circulating regulatory T cells one month post initiation of renal replacement therapy. Clin. Nephrol. 2021, 95, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Moreno, P.L.; Tripathi, S.; Chandraker, A. Regulatory T Cells and Kidney Transplantation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 1760–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaier, M.; Leick, A.; Uhlmann, L.; Kälble, F.; Morath, C.; Eckstein, V.; Ho, A.; Mueller-Tidow, C.; Meuer, S.; Mahnke, K.; et al. End-stage renal disease, dialysis, kidney transplantation and their impact on CD4+ T-cell differentiation. Immunology 2018, 155, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottà, C.; Fanelli, G.; Hoong, S.J.; Romano, M.; Lamperti, E.N.; Sukthankar, M.; Guggino, G.; Fazekasova, H.; Ratnasothy, K.; Becker, P.D.; et al. Impact of immunosuppressive drugs on the therapeutic efficacy of ex vivo expanded human regulatory T cells. Haematologica 2016, 101, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaier, M.; Seissler, N.; Schmitt, E.; Meuer, S.; Hug, F.; Zeier, M.; Steinborn, A. DR(high+)CD45RA(−)-Tregs potentially affect the suppressive activity of the total Treg pool in renal transplant patients. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Wang, Y.M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.Y.; Zheng, G.; Yi, S.; O’Connell, P.J.; Harris, D.C.; Alexander, S.I. Regulatory T cells in kidney disease and transplantation. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl, M.V.; Gollapudi, S.; Sepassi, L.; Gollapudi, P.; Elahimehr, R.; Vaziri, N.D. Effect of end-stage renal disease on B lymphocyte subpopulations, 7, BAFF and BAFF receptor expression. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fresnedo, G.; Ramos, M.A.; González-Pardo, M.C.; de Francisco, A.L.M.; López-Hoyos, M.; Arias, M. B lymphopenia in uremia is related to an accelerated in vitro apoptosis and dysregulation of Bcl-2. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2000, 15, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouts, A.H.M.; Davin, J.C.; Krediet, R.T.; Monnens, L.A.H.; Nauta, J.; Schröder, C.H.; Van Lier, R.A.; Out, T.A. Children with chronic renal failure have reduced numbers of memory B cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004, 137, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Guo, H.; Jin, D.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, L. Distribution characteristics of circulating B cell subpopulations in patients with chronic kidney disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.R.; Hayakawa, K. B cell development pathways. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 19, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciocca, M.; Zaffina, S.; Fernandez Salinas, A.; Bocci, C.; Palomba, P.; Conti, M.G.; Terreri, S.; Frisullo, G.; Giorda, E.; Scarsella, M.; et al. Evolution of human memory B cells from childhood to old age. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 690534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Pahl, M.V.; Crum, A.; Norris, K. Effect of uremia on structure and function of immune system. J. Ren. Nutr. 2012, 22, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peroumal, D.; Jawale, C.V.; Choi, W.; Rahimi, H.; Antos, D.; Li, D.D.; Wang, S.; Manakkat Vijay, G.K.; Mehta, I.; West, R.; et al. The survival of B cells is compromised in kidney disease. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.C.; Allen, P.M. Myosin-induced acute myocarditis is a T cell-mediated disease. J. Immunol. 1991, 147, 2141–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, U.; Beyersdorf, N.; Weirather, J.; Podolskaya, A.; Bauersachs, J.; Ertl, G.; Kerkau, T.; Frantz, S. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation 2012, 125, 1652–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroumanie, F.; Douin-Echinard, V.; Pozzo, J.; Lairez, O.; Tortosa, F.; Vinel, C.; Delage, C.; Calise, D.; Dutaur, M.; Parini, A.; et al. CD4+ T cells promote the transition from hypertrophy to heart failure during chronic pressure overload. Circulation 2014, 129, 2111–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, A.D.; DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y. T cell regulation of fibroblasts and cardiac fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2020, 91, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Vazquez, R.; Zabadi, S.; Watson, R.R.; Larson, D.F. T-lymphocytes mediate left ventricular fibrillar collagen cross-linking and diastolic dysfunction in mice. Matrix Biol. 2010, 29, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevers, T.; Salvador, A.M.; Grodecki-Pena, A.; Knapp, A.; Velázquez, F.; Aronovitz, M.; Kapur, N.K.; Karas, R.H.; Blanton, R.M.; Alcaide, P. Left Ventricular T-Cell Recruitment Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.G.; Dai, J.; Yuan, Y.P.; Bian, Z.Y.; Xu, S.C.; Jin, Y.G.; Zhang, X.; Tang, Q.Z. T-bet deficiency attenuates cardiac remodeling in rats. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2018, 113, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A.M.; Nevers, T.; Velázquez, F.; Aronovitz, M.; Wang, B.; Abadía Molina, A.; Jaffe, I.Z.; Karas, R.H.; Blanton, R.M.; Alcaide, P. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 regulates left ventricular leukocyte infiltration, cardiac remodeling, and function in pressure overload-induced heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwenyama, N.; Salvador, A.M.; Veláázquez, F.; Nevers, T.; Levy, A.; Aronovitz, M.; Luster, A.D.; Huggins, G.S.; Alcaide, P. CXCR3 regulates CD4+ T cell cardiotropism in pressureoverload-induced cardiac dysfunction. JCI Insight 2019, 4, 125527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhang, C.; Hu, J.; Xu, D. Recent advances in understanding the roles of T cells in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2019, 129, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Cesana, F.; Lamperti, E.; Gavras, H.; Yu, J. Attenuation of angiotensin II induced hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice overexpressing a type 1 receptor mutant. Am. J. Hypertens. 2009, 22, 1320–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Miguel, C.; Guo, C.; Lund, H.; Feng, D.; Mattson, D.L. Infiltrating T lymphocytes in the kidney increase oxidative stress and participate in the development of hypertension and renal disease. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2011, 300, F734–F742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AKirabo, V.; Fontana, A.P.; de Faria, R.; Loperena, C.L.; Galindo, J.; Wu, A.T.; Bikineyeva, S.; Dikalov, L.; Xiao, W.; Chen, M.A.; et al. Harrison, DC isoketal-modified proteins activate T cells and promote hypertension. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ilatovskaya, D.V.; Pitts, C.; Clayton, J.; Domondon, M.; Troncoso, M.; Pippin, S.; DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y. CD8(+) T-cells negatively regulate inflammation post-myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 317, H581–H596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komai, K.; Ito, M.; Nomura, S.; Shichino, S.; Katoh, M.; Yamada, S.; Ko, T.; Iizuka-Koga, M.; Nakatsukasa, H.; Yoshimura, A. Single-Cell Analysis Revealed the Role of CD8+ Effector T Cells in Preventing Cardioprotective Macrophage Differentiation in the Early Phase of Heart Failure. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 763647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Rafferty, T.M.; Rhee, S.W.; Webber, J.S.; Song, L.; Ko, B.; Hoover, R.S.; He, B.; Mu, S. CD8+ T cells stimulate Na-Cl co-transporter NCC in distal convoluted tubules leading to saltsensitive hypertension. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, L.N.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Rhee, S.W.; Guo, Y.; Deck, K.S.; Mora, C.J.; Li, L.X.; Huang, L.; et al. The IFNγ-PDL1 pathway enhances CD8T-DCT interaction to promote hypertension. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, L.N.; Liu, Y.; Deck, K.S.; Mora, C.; Mu, S. Interferon Gamma contributes to the immune mechanisms of hypertension. Kidney 360 2022, 3, 2164–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale, D.; Carnevale, L.; Perrotta, S.; Pallante, F.; Migliaccio, A.; Iodice, D.; Perrotta, M.; Lembo, G. Chronic 3D vascular-immune interface established by coculturing pressurized resistance arteries and immune cells. Hypertension 2021, 78, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.C.; Yu, H.T.; Lim, B.J.; Koh, M.J.; Lee, J.; Chang, D.Y.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, S.H.; Kang, S.M.; Jang, Y.; et al. Immunosenescent CD8+ T cells and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3 chemokines are increased in human hypertension. Hypertension 2013, 62, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, H.A.; McMaster, W.G.; Saleh, M.A.; Nazarewicz, R.R.; Mikolajczyk, T.P.; Kaszuba, A.M.; Konior, A.; Prejbisz, A.; Januszewicz, A.; Norlander, A.E.; et al. Activation of human T cells in hypertension: Studies of humanized mice and hypertensive humans. Hypertension 2016, 68, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterberg, P.D.; Robertson, J.M.; Kelleman, M.S.; George, R.P.; Ford, M.L. T Cells Play a Causal Role in Diastolic Dysfunction during Uremic Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Yuan, W. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota Contributes to Uremic Cardiomyopathy via Induction of IFNgamma-Producing CD4(+) T Cells Expansion. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0310122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duni, A.; Kitsos, A.; Bechlioulis, A.; Lakkas, L.; Markopoulos, G.; Tatsis, V.; Koutlas, V.; Tzalavra, E.; Baxevanos, G.; Vartholomatos, G.; et al. Identification of Novel Independent Correlations Between Cellular Components of the Immune System and Strain-Related Indices of Myocardial Dysfunction in CKD Patients and Kidney Transplant Recipients Without Established Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnakamene, J.B.; Safar, M.E.; Levy, B.I.; Escoubet, B. Left ventricular torsion associated with aortic stiffness in hypertension. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panoulas, V.F.; Sulemane, S.; Konstantinou, K.; Bratsas, A.; Elliott, S.J.; Dawson, D.; Frankel, A.H.; Nihoyannopoulos, P. Early detection of subclinical left ventricular myocardial dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Eur. Heart J.-Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkas, L.; Naka, K.K.; Bechlioulis, A.; Girdis, I.; Duni, A.; Koutlas, V.; Moustakli, M.; Katsouras, C.S.; Dounousi, E.; Michalis, L.K. The prognostic role of myocardial strain indices and dipyridamole stress test in renal transplantation patients. Echocardiography 2020, 37, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriott, J.B.; Goldman, J.H.; Keeling, P.J.; Baig, M.K.; Dalgleish, A.G.; McKenna, W.J. Abnormal cytokine profiles in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and their asymptomatic relatives. Heart 1996, 75, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathes, D.; Weirather, J.; Nordbeck, P.; Arias-Loza, A.P.; Burkard, M.; Pachel, C.; Kerkau, T.; Beyersdorf, N.; Frantz, S.; Hofmann, U. CD4 Foxp3 T-cells contribute to myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 101, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Linthout, S.; Tschöpe, C. Inflammation-Cause or Consequence of Heart Failure or Both? Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2017, 14, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisel, A.S.; Knowlton, K.U.; Fowler, P.; Rearden, A.; Ziegler, M.G.; Motulsky, H.J.; Insel, P.A.; Michel, M.C. Adrenergic control of circulating lymphocyte subpopulations. Effects of congestive heart failure, dynamic exercise, and terbutaline treatment. J. Clin. Investig. 1990, 85, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Ambrosy, A.P.; Greene, S.J.; Mentz, R.J.; Subacius, H.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Swedberg, S.; Nodari, S.; Zannad, F.; Konstam, M.A.; et al. Predictive value of low relative lymphocyte count in patients hospitalized for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Insights from the EVEREST trial. Circ. Heart Fail. 2012, 5, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charach, G.; Grosskopf, I.; Roth, A.; Afek, A.; Wexler, D.; Sheps, D.; Weintraub, M.; Rabinovich, A.; Keren, G.; George, J. Usefulness of total lymphocyte count as predictor of outcome in patients with chronic heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 107, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakatani, T.; Hadase, M.; Kawasaki, T.; Kamitani, T.; Kawasaki, S.; Sugihara, H. Usefulness of the percentage of plasma lymphocytes as a prognostic marker in patients with congestive heart failure. Jpn. Heart J. 2004, 45, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, W.C.; Mozaffarian, D.; Linker, D.T.; Sutradhar, S.C.; Anker, S.D.; Cropp, A.B.; Anand, I.; Maggioni, A.; Burton, P.; Sullivan, M.D.; et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation 2006, 113, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duni, A.; Kitsos, A.; Bechlioulis, A.; Markopoulos, G.S.; Lakkas, L.; Baxevanos, G.; Mitsis, M.; Vartholomatos, G.; Naka, K.K.; Dounousi, E. Differences in the Profile of Circulating Immune Cell Subsets in Males with Type 2 Cardiorenal Syndrome versus CKD Patients Without Established Cardiovascular Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernier, I.C.S.; Neres-Santos, R.S.; Andrade-Oliveira, V.; Carneiro-Ramos, M.S. Cells. Immune Cells Are Differentially Modulated in the Heart and the Kidney during the Development of Cardiorenal Syndrome 3. Cells 2023, 12, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Tang, B.; He, G.; Feng, Z.; Hao, W.; Hu, W. B lymphocytes subpopulations are associated with cardiac remodeling in elderly patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 163, 111805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Peng, B.; Zhuang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ming, Y. Machine learning-based investigation of the relationship between immune status and left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with end-stage kidney disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1187965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, M.; Allende, L.M.; Ramos, L.E.; Gutiérrez, E.; Pleguezuelo, D.E.; Hernández, E.R.; Ríos, F.; Fernández, C.; Praga, M.; Morales, E. CD19+ B-Cells, a New Biomarker of Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duni, A.; Vartholomatos, G.; Balafa, O.; Ikonomou, M.; Tseke, P.; Lakkas, L.; Rapsomanikis, K.P.; Kitsos, A.; Theodorou, I.; Pappas, C.; et al. The Association of Circulating CD14++ CD16+ Monocytes, Natural Killer Cells and Regulatory T Cells Subpopulations with Phenotypes of Cardiovascular Disease in a Cohort of Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 724316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Yang, J.; Dong, M.; Zhang, K.; Tu, E.; Gao, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. Regulatory T cells in cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A.; Dobaczewski, M.; Rai, V.; Haque, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, N.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Regulatory T cells are recruited in the infarcted mouse myocardium and may modulate fibroblast phenotype and function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014, 307, H1233–H1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.T.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, Z.F.; Zhang, W.C.; Xiao, H.; Xia, N.; Yan, X.X.; Nie, S.F.; Liu, J.; Zhou, S.F.; et al. Regulatory T cells ameliorate cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2012, 107, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirather, J.; Hofmann, U.D.; Beyersdorf, N.; Ramos, G.C.; Vogel, B.; Frey, A.; Ertl, G.; Kerkau, T.; Frantz, S. Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells improve healing after myocardial infarction by modulating monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.S.; Ismahil, M.A.; Goel, M.; Zhou, G.; Rokosh, G.; Hamid, T.; Prabhu, S.D. Dysfunctional and proinflammatory regulatory T-lymphocytes are essential for adverse cardiac remodeling in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2019, 139, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, A.; Sulzgruber, P.; Koller, L.; Kazem, N.; Hofer, F.; Richter, B.; Blum, S.; Hülsmann, M.; Wojta, J.; Niessner, A. The Prognostic Impact of Circulating Regulatory T Lymphocytes on Mortality in Patients with Ischemic Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 6079713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, N.; Noma, T.; Ishihara, Y.; Miyauchi, Y.; Takabatake, W.; Oomizu, S.; Yamaoka, G.; Ishizawa, M.; Namba, T.; Murakami, K.; et al. Prognostic value of circulating regulatory T cells for worsening heart failure in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Int. Heart J. 2014, 55, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassan, M.; Wecker, A.; Kadowitz, P.; Trebak, M.; Matrougui, K. CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3 regulatory T cells and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2013, 31, 1939–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerson, A.; Trevelin, S.C.; Mongue-Din, H.; Becker, P.D.; Ortiz, C.; Smyth, L.A.; Peng, Q.; Elgueta, R.; Sawyer, G.; Ivetic, A.; et al. Nox2 in regulatory T cells promotes angiotensin II-induced cardiovascular remodeling. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3088–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasal, D.A.; Barhoumi, T.; Li, M.W.; Yamamoto, N.; Zdanovich, E.; Rehman, A.; Neves, M.F.; Laurant, P.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent aldosterone-induced vascular injury. Hypertension 2012, 59, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvakan, H.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Qadri, F.; Park, J.K.; Fischer, R.; Schwarz, I.; Rahn, H.P.; Plehm, R.; Wellner, M.; Elitok, S.; et al. Regulatory T cells ameliorate angiotensin II-induced cardiac damage. Circulation 2009, 119, 2904–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mian, M.O.R.; Barhoumi, T.; Briet, M.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L. Deficiency of T-regulatory cells exaggerates angiotensin II-induced microvascular injury by enhancing immune responses. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Feng, Y.; Gong, C.; Bao, X.; Wei, Z.; Chang, L.; Chen, H.; Xu, B. Hypertension-Driven Regulatory T-Cell Perturbations Accelerate Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Hypertension 2023, 80, 2046–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Eirin, A.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Krier, J.D.; Tang, H.; Jordan, K.L.; Woollard, J.R.; Taner, T.; Lerman, A.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Induce Regulatory T Cells to Ameliorate Chronic Kidney Injury. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Fan, J.; Zeng, Q.; Cai, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, S.Y.; Cui, Q.; Yang, J.; et al. CD4(+) T-Cell Endogenous Cystathionine gamma Lyase-Hydrogen Sulfide Attenuates Hypertension by Sulfhydrating Liver Kinase B1 to Promote T Regulatory Cell Differentiation and Proliferation. Circulation 2020, 142, 1752–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.R.; Dale, B.L.; Smart, C.D.; Elijovich, F.; Wogsland, C.E.; Lima, S.M.; Irish, J.M.; Madhur, M.S. Immune Profiling Reveals Decreases in Circulating Regulatory and Exhausted T Cells in Human Hypertension. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2023, 8, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Tan, F.; Yuan, X.; Du, J. The roles of B cells in cardiovascular diseases. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 171, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, L.; Rocha-Resende, C.; Lin, C.Y.; Evans, S.; Williams, J.; Dun, H.; Li, W.; Mpoy, C.; Andhey, P.S.; Rogers, B.E.; et al. Myocardial B cells are a subset of circulating lymphocytes with delayed transit through the heart. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e134700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, M.; Ashour, D.; Siegel, J.; Büchner, L.; Wedekind, G.; Heinze, K.G.; Arampatzi, P.; Saliba, A.E.; Cochain, C.; Hofmann, U.; et al. The healing myocardium mobilizes a distinct B-cell subset through a CXCL13-CXCR5-dependent mechanism. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 2664–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wen, S.; Wang, M.; Liang, W.; Li, H.H.; Long, Q.; Guo, H.P.; Liao, Y.H.; Yuan, J. TNF-α-secreting B cells contribute to myocardial fibrosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Immunol. 2013, 33, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Lu, Y.Z.; Xia, N.; Wang, Y.Q.; Tang, T.T.; Nie, S.F.; Lv, B.J.; Wang, K.J.; Wen, S.; Li, J.Y.; et al. Defective Circulating Regulatory B Cells in Patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 46, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Reyes, A.M.; Youker, K.A.; Trevino, A.R.; Celis, R.; Hamilton, D.J.; Flores-Arredondo, J.H.; Orrego, C.M.; Bhimaraj, A.; Estep, J.D.; Torre-Amione, G. Full Expression of Cardiomyopathy Is Partly Dependent on B-Cells: A Pathway That Involves Cytokine Activation, Immunoglobulin Deposition, and Activation of Apoptosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolgovsky, S.; Bayer, A.L.; Aronovitz, M.; Vanni, K.M.M.; Kirabo, A.; Harrison, D.G.; Alcaide, P. Experimental pressure overload induces a cardiac neoantigen specific humoral immune response. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2025, 201, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Geng, C.; Chen, Y.; Pang, J.; Shu, T.; Zhao, M.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, B.; et al. Role of IgE-FcepsilonR1 in Pathological Cardiac Remodeling and Dysfunction. Circulation 2021, 143, 1014–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Shan, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xue, Y.; et al. Spleen-Heart Cross-Talk Through CD23-Mediated Signal Promotes Cardiac Remodeling. Circ. Res. 2025, 137, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolgovsky, S.; Alcaide, P. Splenic CD23+ B Cells: Preventing Adverse Remodeling by Limiting IgE Production. Circ. Res. 2025, 137, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Otaki, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Yamaguchi, R.; Ono, H.; Tachibana, S.; Sato, J.; Hashimoto, N.; Wanezaki, M.; Kutsuzawa, D.; et al. Circulating CD19 B cell count, myocardial injury and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2025, 12, 3512–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazoe, M.; Ting, K.K.Y.; Lee, I.H.; Bapat, A.; Lewis, A.; Xiao, L.; Pulous, F.E.; Mentkowski, K.; Paccalet, A.; Momin, N.; et al. B cells promote atrial fibrillation via autoantibodies. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 4, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rivas, G.; Castillo, E.C.; Gonzalez-Gil, A.M.; Maravillas-Montero, J.L.; Brunck, M.; Torres-Quintanilla, A.; Elizondo-Montemayor, L.; Torre-Amione, G. The role of B cells in heart failure and implications for future immunomodulatory treatment strategies. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 1387–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Tang, B.; Feng, Z.; Hao, W.; Hu, W. Decreased B lymphocytes subpopulations are associated with higher atherosclerotic risk in elderly patients with moderate-to-severe chronic kidney diseases. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattarabanjird, T.; Li, C.; McNamara, C. B Cells in Atherosclerosis: Mechanisms and Potential Clinical Applications. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2021, 6, 546–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Devalaraja, M.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Engelmann, M.D.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Ivkovic, M.; Lo, L.; Kling, D.; Pergola, P.; Raj, D.; et al. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2060–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.X.; Kostapanos, M.; Griffiths, C.; Arbon, E.L.; Hubsch, A.; Kaloyirou, F.; Helmy, J.; Hoole, S.P.; Rudd, J.H.F.; Wood, G.; et al. Low-dose interleukin-2 in patients with stable ischaemic heart disease and acute coronary syndromes (LILACS): Protocol and study rationale for a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase I/II clinical trial. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Duni, A.; Georgopoulos, C.; Kitsos, A.; Markopoulos, G.; Dova, L.; Vartholomatos, G.; Dounousi, E. Signaling Pathways of the Acquired Immune System and Myocardial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease—What Do We Know So Far? Biomolecules 2026, 16, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010049

Duni A, Georgopoulos C, Kitsos A, Markopoulos G, Dova L, Vartholomatos G, Dounousi E. Signaling Pathways of the Acquired Immune System and Myocardial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease—What Do We Know So Far? Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuni, Anila, Christos Georgopoulos, Athanasios Kitsos, Georgios Markopoulos, Lefkothea Dova, Georgios Vartholomatos, and Evangelia Dounousi. 2026. "Signaling Pathways of the Acquired Immune System and Myocardial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease—What Do We Know So Far?" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010049

APA StyleDuni, A., Georgopoulos, C., Kitsos, A., Markopoulos, G., Dova, L., Vartholomatos, G., & Dounousi, E. (2026). Signaling Pathways of the Acquired Immune System and Myocardial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease—What Do We Know So Far? Biomolecules, 16(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010049