Electrochemical Choline Sensing: Biological Context, Electron Transfer Pathways and Practical Design Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Choline Biology, Distribution and Analytical Requirements

2.1. Biological Roles, Matrices, and Typical Concentration Ranges

2.2. Temporal Dynamics, Turnover and Sampling Considerations

2.3. Interferent Profiles and Matrix-Matched Challenges

2.4. Implications for Sensor Specification

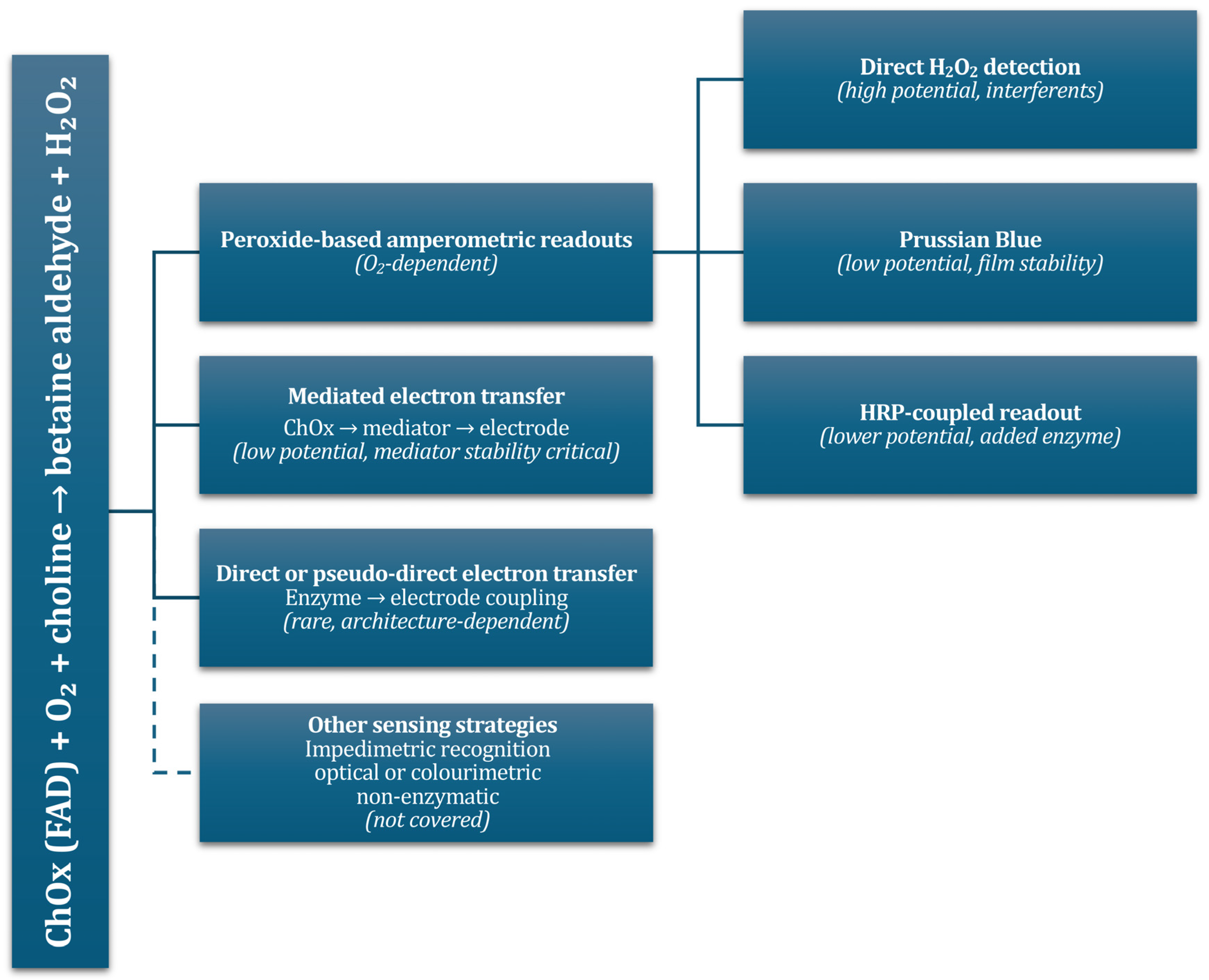

3. Electron Transfer Pathways and Design Strategies for Enzymatic Choline Sensors

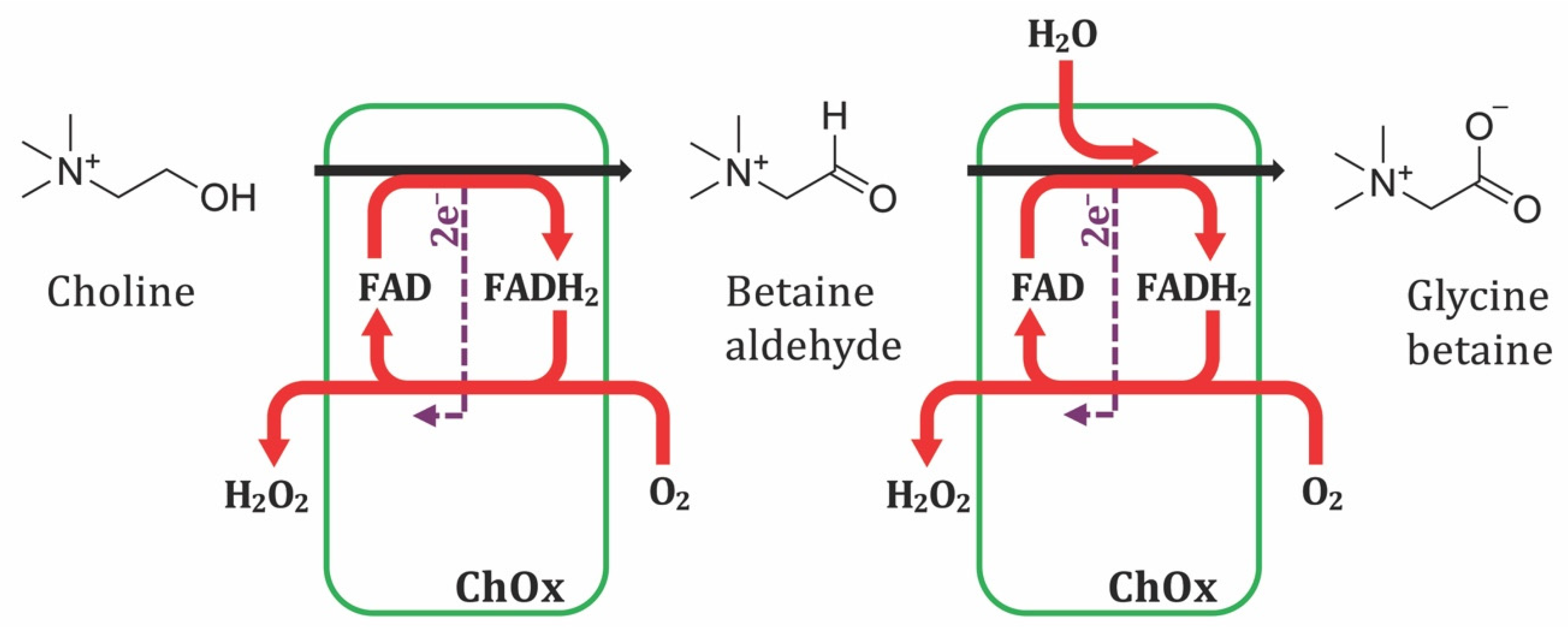

3.1. Mechanistic Fundamentals

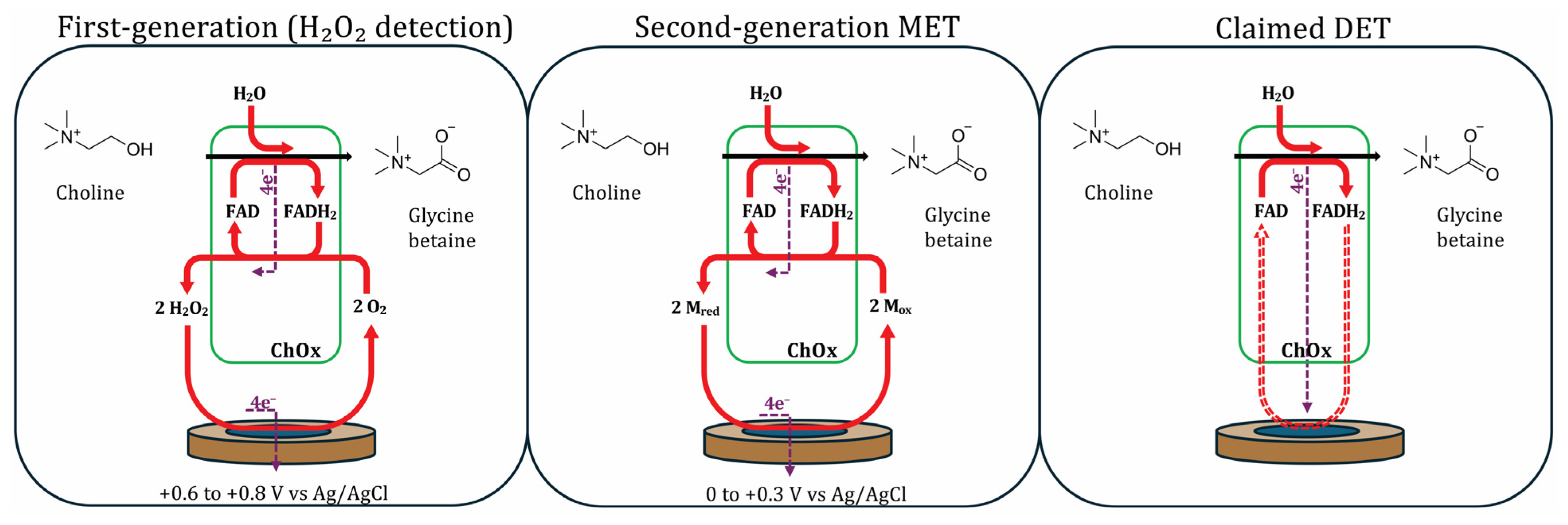

3.2. First-Generation Sensors

3.3. Second-Generation Sensors—Mediated Electron Transfer

3.4. Direct Electron Transfer with Choline Oxidase

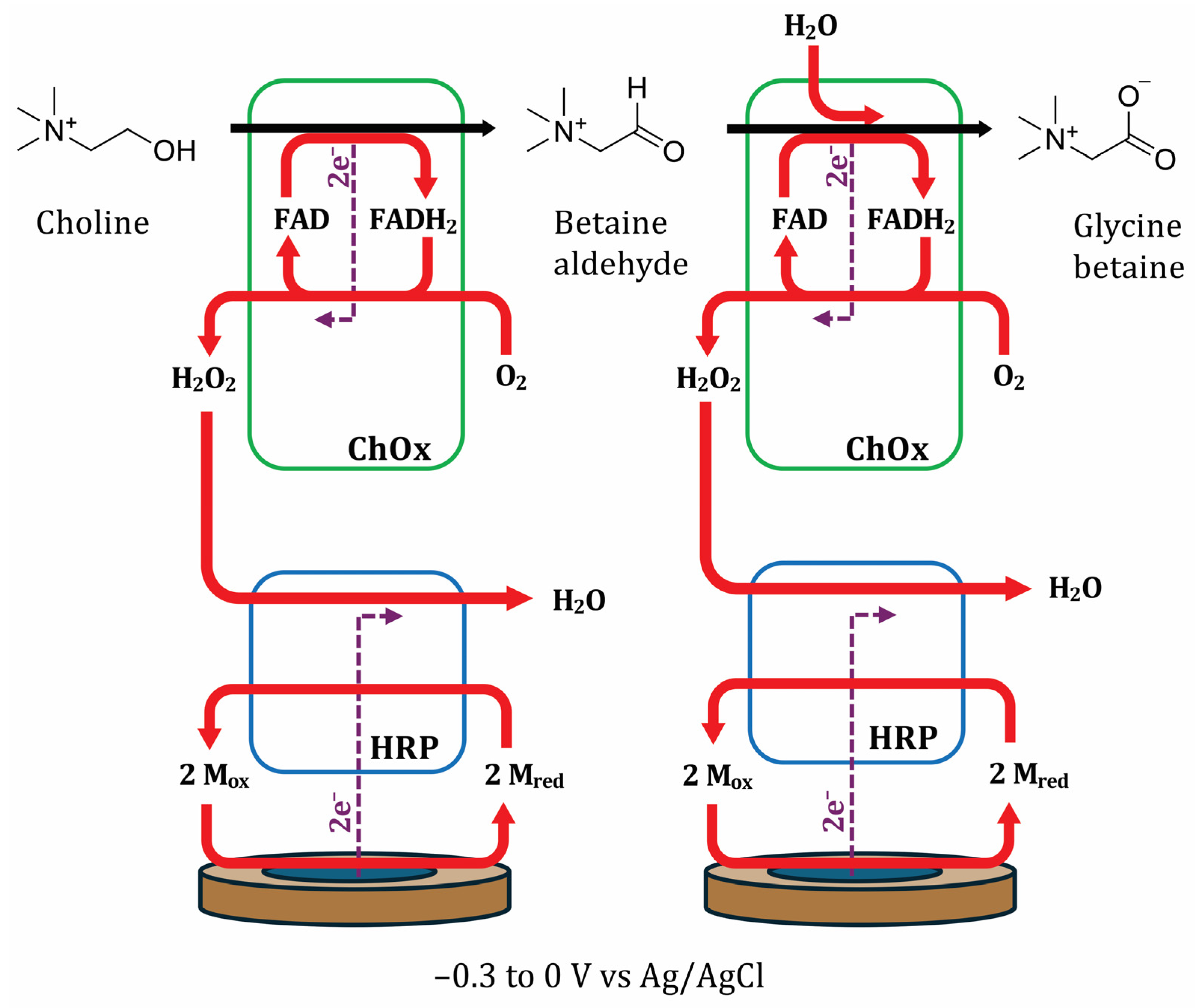

3.5. Bienzymatic Choline Oxidase and Horseradish Peroxidase

3.6. Operational pH Window for ChOx with and Without HRP

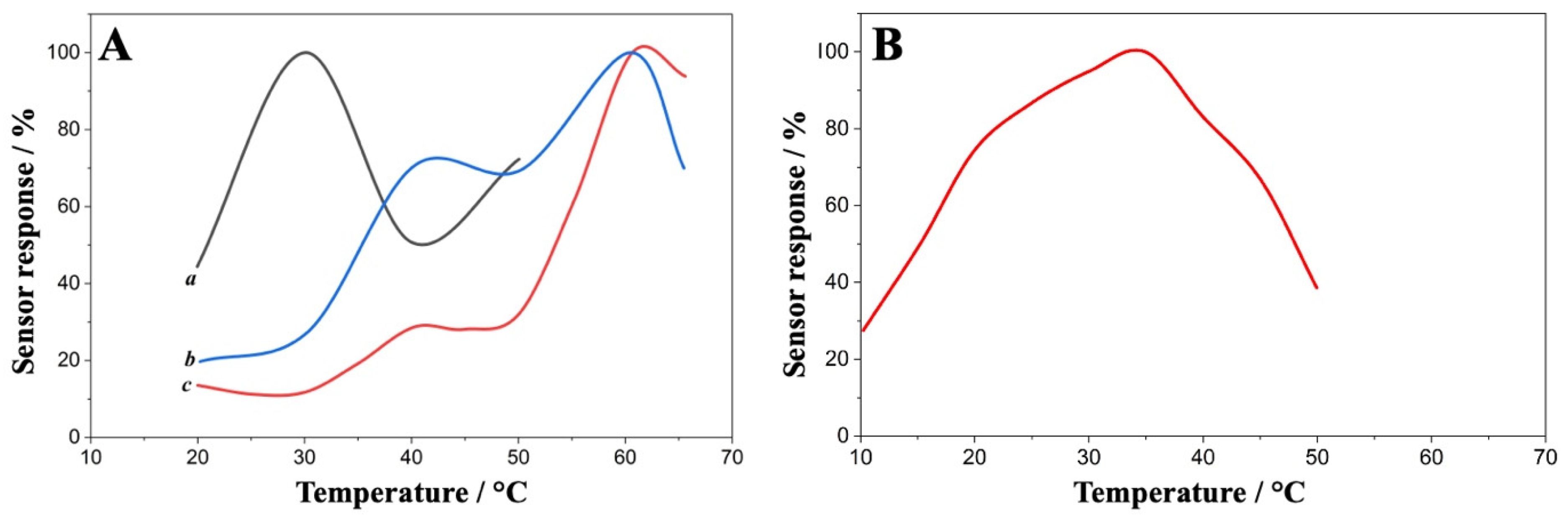

3.7. Operational Temperature Window for ChOx with and Without HRP

3.8. Non-Enzymatic and Neutral-pH Strategies

4. Platforms and Form Factors (Matrix-Matched)

5. Validation and Reporting Standards

6. Meta-Analysis and Design Trade-Offs

6.1. Comparative Performance Across Architectures

6.2. Outstanding Challenges and Future Directions

7. Translational Use Cases

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACh | acetylcholine |

| AuNP | gold nanoparticles |

| AuNr | gold nanorods |

| BL-MWCNT | bamboo-like multi-walled carbon nanotube |

| bpy | 2,2′-bipyridine |

| CB | carbon black |

| ChOx | choline oxidase |

| CPE | carbon paste electrode |

| CNF | carbon nanofibres |

| CNF-MnO2 | MnO2 nanoparticles decorated carbon nanofibres |

| CNT | carbon nanotube |

| CPME | poly-5,2′:5′,2″-terthiophene-3′-carboxylic acid modified electrode |

| CRGO | chemically reduced graphene oxide |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CSPE | carbon screen-printed electrode |

| DET | direct electron transfer |

| EACC | 6-O-ethoxytrimethylammoniochitosan chloride |

| ECS | extracellular space |

| GC | glassy carbon |

| GNP | gold nanoparticles |

| GPC | glycerophosphocholine |

| HRP | horseradish peroxidase |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| IL | ionic liquid |

| ISE | ion-selective electrode |

| LC | liquid chromatography |

| LC-MS/MS | liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| LoD | limit of detection |

| MB | meldola blue |

| MEA | microelectrode array |

| MET | mediated electron transfer |

| m-PD | meta-phenylenediamine |

| MWCNT | multi-walled carbon nanotube |

| NH2-MWCNTs | amine-functionalised multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| NWs | nanowires |

| PANI | polyaniline |

| PB | Prussian blue |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| PC | phosphatidylcholine |

| PDDA | poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) |

| PMG | poly(methylene green) |

| PPy | polypyrrole |

| Pt | platinum |

| PTH | poly(thionine) |

| PVA | polyvinyl alcohol |

| PVP | poly(4-vinylpyridine) |

| PVS | polyvinylsulphonate |

| SBA-15 | mesoporous silica powder |

| SCE | saturated calomel electrode |

| SHE | standard hydrogen electrode |

| SPCE | screen-printed carbon electrode |

| TBO | toluidine blue O |

| TD-p-AgSA | tubular detector of polished silver solid amalgam |

| TTCA | 5,2′:5′,2″-terthiophene-3′-carboxylic acid |

References

- Zeisel, S.H. Choline: Critical Role During Fetal Development and Dietary Requirements in Adults. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2006, 26, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisel, S.H.; Blusztajn, J.K. Choline and Human Nutrition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1994, 14, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisel, S.H.; da Costa, K.A. Choline: An essential nutrient for public health. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbyshire, E.; Obeid, R. Choline, Neurological Development and Brain Function: A Systematic Review Focusing on the First 1000 Days. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, M.U.; Yaqub, A.; Khan, M.H.; Yaseen, F.; Jilani, S.; Ajab, H.; Shah, N.S.; Al-Anazi, A. Nanotechnology-driven electrochemical neurotransmitter sensing as a fundamental approach towards improving diagnostics and therapeutics: A review. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2025, 9, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zuo, Y.; Chen, S.; Hatami, A.; Gu, H. Advancements in Brain Research: The In Vivo/In Vitro Electrochemical Detection of Neurochemicals. Biosensors 2024, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wang, X. An overview of recent analysis and detection of acetylcholine. Anal. Biochem. 2021, 632, 114381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, J.; Sharma, M.; Shekhar Pundir, C. Advances in biosensor development for detection of acetylcholine. Microchem. J. 2023, 190, 108620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.D.; Jeong, C.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, D.-S.; Yoon, H.C. Microchip-Based Organophosphorus Detection Using Bienzyme Bioelectrocatalysis. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 51, 06FK01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Lan, Q.-Y.; Tian, F.; Xiong, X.-Y.; Yang, M.-T.; Huang, S.-Y.; Chen, X.-Y.; Kuchan, M.J.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.-R.; et al. Longitudinal changes in choline concentration and associated factors in human breast milk. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, S.; Aihemaitijiang, S.; Li, H.; Liu, J. Choline concentration and composition in human milk across lactation stages: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, P.I.; Ueland, P.M.; Kvalheim, G.; Lien, E.A. Determination of choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine in plasma by a high-throughput method based on normal-phase chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elble, R.; Giacobini, E.; Higgins, C. Choline levels are increased in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer patients. Neurobiol. Aging 1989, 10, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamy, E.; Pilyser, L.; Paquet, C.; Bouaziz-Amar, E.; Grassin-Delyle, S. High-sensitivity quantification of acetylcholine and choline in human cerebrospinal fluid with a validated LC-MS/MS method. Talanta 2021, 224, 121881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapiro, M.B.; Atack, J.R.; Hanin, I.; May, C.; Haxby, J.V.; Rapoport, S.I. Lumbar Cerebrospinal Fluid Choline in Healthy Aging and in Down’s Syndrome. Arch. Neurol. 1990, 47, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Gonzalez, R.; Köppen, A.; Löffelholz, K. Free choline and choline metabolites in rat brain and body fluids: Sensitive determination and implications for choline supply to the brain. Neurochem. Int. 1993, 22, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.L.; Bolger, F.B.; Lowry, J.P. A microelectrochemical biosensor for real-time in vivo monitoring of brain extracellular choline. Analyst 2015, 140, 3738–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garguilo, M.G.; Michael, A.C. Amperometric microsensors for monitoring choline in the extracellular fluid of brain. J. Neurosci. Methods 1996, 70, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.M.; Laranjinha, J.; Barbosa, R.M.; Sirota, A. Simultaneous measurement of cholinergic tone and neuronal network dynamics in vivo in the rat brain using a novel choline oxidase based electrochemical biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 69, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artegoitia, V.M.; Middleton, J.L.; Harte, F.M.; Campagna, S.R.; de Veth, M.J. Choline and Choline Metabolite Patterns and Associations in Blood and Milk during Lactation in Dairy Cows. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Veth, M.J.; Artegoitia, V.M.; Campagna, S.R.; Lapierre, H.; Harte, F.; Girard, C.L. Choline absorption and evaluation of bioavailability markers when supplementing choline to lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9732–9744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.J.R.; Kononoff, P.J. Appearance of choline metabolites in plasma and milk when choline is infused into the abomasum with or without methionine. JDS Commun. 2023, 4, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanaugh, S.M.; Cavanaugh, R.P.; Streeter, R.; Vieira, A.B.; Gilbert, G.E.; Ketzis, J.K. Commercial Extruded Plant-Based Diet Lowers Circulating Levels of Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) Precursors in Healthy Dogs: A Pilot Study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 936092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burri, L.; Heggen, K.; Storsve, A.B. Phosphatidylcholine from krill increases plasma choline and its metabolites in dogs. Vet. World 2019, 12, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, J.P.; Gash, C.; Martin, B.; Zmarowski, A.; Pomerleau, F.; Burmeister, J.; Huettl, P.; Gerhardt, G.A. Second-by-second measurement of acetylcholine release in prefrontal cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 24, 2749–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Gadda, G. On the Catalytic Mechanism of Choline Oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2067–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadda, G. Chapter Six—Choline oxidases. In The Enzymes; Chaiyen, P., Tamanoi, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 47, pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem, M.; Gadda, G. On the catalytic role of the conserved active site residue His466 of choline oxidase. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orville, A.M.; Lountos, G.T.; Finnegan, S.; Gadda, G.; Prabhakar, R. Crystallographic, spectroscopic, and computational analysis of a flavin C4a− Oxygen adduct in choline oxidase. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, O.; Lountos, G.T.; Fan; Orville, A.M.; Gadda, G. Role of Glu312 in binding and positioning of the substrate for the hydride transfer reaction in choline oxidase. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mruthunjaya, A.K.V.; Hodges, A.M.; Chatelier, R.C.; Torriero, A.A.J. Calibration-Free Disposable Electrochemical Sensor with Co-Facing Electrodes: Theory and Characterisation with Fixed and Changing Mediator Concentration. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 460, 142596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, J.J.; Gerhardt, G.A. Self-referencing ceramic-based multisite microelectrodes for the detection and elimination of interferences from the measurement of L-glutamate and other analytes. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, V.; Sarter, M. Cortical choline transporter function measured in vivo using choline-sensitive microelectrodes: Clearance of endogenous and exogenous choline and effects of removal of cholinergic terminals. J. Neurochem. 2006, 97, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Dauphin-Ducharme, P.; Ortega, G.; Plaxco, K.W. Calibration-free electrochemical biosensors supporting accurate molecular measurements directly in undiluted whole blood. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11207–11213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, S.A.; Goggins, S.; Frost, C.G. Ratiometric Electrochemistry: Improving the Robustness, Reproducibility and Reliability of Biosensors. Molecules 2021, 26, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, M.; Santhoshkumar, S.; Tseng, W.-B.; Tseng, W.-L. Maximizing analytical precision: Exploring the advantages of ratiometric strategy in fluorescence, Raman, electrochemical, and mass spectrometry detection. Front. Anal. Sci. 2023, 3, 1258558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, R.; Guerrieri, A. A Crosstalk- and Interferent-Free Dual Electrode Amperometric Biosensor for the Simultaneous Determination of Choline and Phosphocholine. Sensors 2021, 21, 3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M. A label-free fluorescence biosensor based on a bifunctional MIL-101(Fe) nanozyme for sensitive detection of choline and acetylcholine at nanomolar level. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 312, 128021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Ou, Z.; Chen, Q.; Wu, B. Amperometric acetylcholine biosensor based on self-assembly of gold nanoparticles and acetylcholinesterase on the sol‚Äìgel/multi-walled carbon nanotubes/choline oxidase composite-modified platinum electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 33, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadana, A. Engineering Biosensors: Kinetics and Design Applications; Academic Press (Elsevier): San Diego, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.D.; Jang, Y.H.; Yoon, H.C. Cascadic Multienzyme Reaction-Based Electrochemical Biosensors. In Biosensors Based on Aptamers and Enzymes; Gu, M.B., Kim, H.-S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 221–251. [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk, M.; Brashear, R.J.; Mattingly, P.G. Choline Concentration in Normal Blood Donor and Cardiac Troponin–Positive Plasma Samples. Clin. Chem. 2006, 52, 2123–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albishri, H.M.; Abd El-Hady, D. Hyphenation of enzyme/graphene oxide-ionic liquid/glassy carbon biosensors with anodic differential pulse stripping voltammetry for reliable determination of choline and acetylcholine in human serum. Talanta 2019, 200, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lountos, G. Structural and Mechanistic Insights from High Resolution Crystal Structures of the Toluene-4-Monooxygenase Catalytic Effector Protein, NAD(P)H Oxidase and Choline Oxidase. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, K.L.; Bolger, F.B.; Lowry, J.P. Development of a microelectrochemical biosensor for the real-time detection of choline. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 243, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, X.; Anzai, J.-i.; Osa, T.; Chen, Q. Amperometric choline biosensors prepared by layer-by-layer deposition of choline oxidase on the Prussian blue-modified platinum electrode. Talanta 2006, 70, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keihan, A.H.; Sajjadi, S.; Sheibani, N.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A. A highly sensitive choline biosensor based on bamboo-like multiwall carbon nanotubes/ionic liquid/Prussian blue nanocomposite. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 204, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Huang, J.-D.; Wu, B.-Y.; Shi, H.-B.; Anzai, J.-I.; Chen, Q. Amperometric aqueous sol–gel biosensor for low-potential stable choline detection at multi-wall carbon nanotube modified platinum electrode. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2006, 115, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Tang, F.; Liao, R.; Zhang, L. Using gold nanorods to enhance the current response of a choline biosensor. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 7248–7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, P.; Ghourchian, H.; Sajjadi, S. Effect of hydrophilicity of room temperature ionic liquids on the electrochemical and electrocatalytic behaviour of choline oxidase. Analyst 2012, 137, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F.; Amine, A.; Palleschi, G.; Moscone, D. Prussian Blue based screen printed biosensors with improved characteristics of long-term lifetime and pH stability. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2003, 18, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Miao, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhao, W.; Shan, M.; Chen, Q. Amperometric biosensors based on gold nanoparticles-decorated multiwalled carbon nanotubes-poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) biocomposite for the determination of choline. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 147, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Peng, H.; Zhu, J. Improved enzyme immobilization for enhanced bioelectrocatalytic activity of choline sensor and acetylcholine sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 193, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, Y.; Wu, P.; Cai, C. Indirect electrocatalytic determination of choline by monitoring hydrogen peroxide at the choline oxidase-prussian blue modified iron phosphate nanostructures. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 31, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, A.J.; Faulkner, L.R. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Torriero, A.A.J. Comments and Protocols for the Construction and Calibration of Ag/AgCl Reference Electrodes. Int. J. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 8, 000219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meites, L. Handbook of analytical chemistry. Soil Sci. 1963, 96, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Tang, L.; Shen, G.; Yu, R. Inhibition biosensor for determination of nicotine. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 509, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Zhou, J.; Li, X. Noncovalent nanohybrid of ferrocene with chemically reduced graphene oxide and its application to dual biosensor for hydrogen peroxide and choline. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 95, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtemeri, L.; Hickey, D.P. Model-driven design of redox mediators: Quantifying the impact of quinone structure on bioelectrocatalytic activity with glucose oxidase. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 7685–7693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Gadda, G.; Hamelberg, D. The cluster of hydrophobic residues controls the entrance to the active site of choline oxidase. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 9599–9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollella, P.; Katz, E. Enzyme-Based Biosensors: Tackling Electron Transfer Issues. Sensors 2020, 20, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degani, Y.; Heller, A. Direct electrical communication between chemically modified enzymes and metal electrodes. I. Electron transfer from glucose oxidase to metal electrodes via electron relays, bound covalently to the enzyme. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 1285–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Reginald, S.S.; Sravan, J.S.; Lee, M.; Chang, I.S. Advanced strategies for enzyme–electrode interfacing in bioelectrocatalytic systems. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 1328–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazek, T.; Gorski, W. Oxidases, carbon nanotubes, and direct electron transfer: A cautionary tale. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 163, 112260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceres, D.M.; Udit, A.K.; Hill, H.D.; Hill, M.G.; Barton, J.K. Differential ionic permeation of DNA-modified electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, R.; Yan, F. Dual-mode electrochemiluminescence and electrochemical sensor for alpha-fetoprotein detection in human serum based on vertically ordered mesoporous silica films. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1023998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauritz, K.A.; Moore, R.B. State of understanding of Nafion. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4535–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, B. Ruthenium-Based Sensors. Inorganics 2024, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M. Charge transport in solid polymer matrixes with redox centers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2001, 26, 1101–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, C.; Bertrand, P. Direct electrochemistry of redox enzymes as a tool for mechanistic studies. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2379–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Simoska, O.; Lim, K.; Grattieri, M.; Yuan, M.; Dong, F.; Lee, Y.S.; Beaver, K.; Weliwatte, S.; Gaffney, E.M. Fundamentals, applications, and future directions of bioelectrocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12903–12993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçar, C. Disposable Bienzymatic Choline Biosensor Based on MnO2 Nanoparticles Decorated Carbon Nanofibers and Poly(methylene green) Modified Screen Printed Carbon Electrode. Electroanalysis 2020, 32, 2118–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, N.; Ruzgas, T.; Gorton, L.; Kokaia, M.; Kissinger, P.; Csöregi, E. Design and development of an amperometric biosensor for acetylcholine determination in brain microdialysates. Electrochim. Acta 1998, 43, 3541–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Yamamoto, K. Glucose and choline on-line biosensors based on electropolymerized Meldola’s blue. Talanta 2000, 51, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Park, D.-S.; Shim, Y.-B. A performance comparison of choline biosensors: Anodic or cathodic detections of H2O2 generated by enzyme immobilized on a conducting polymer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2004, 19, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, E.; Torriero, A.A.J.; Sanz, M.I.; Battaglini, F.; Raba, J. Continuous-flow system for horseradish peroxidase enzyme assay comprising a packed-column, an amperometric detector and a rotating bioreactor. Talanta 2005, 66, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, G.; Lin, Y. Amperometric choline biosensor fabricated through electrostatic assembly of bienzyme/polyelectrolyte hybrid layers on carbon nanotubes. Analyst 2006, 131, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuoc, L.T.; Laveille, P.; Chamouleau, F.; Renard, G.; Drone, J.; Coq, B.; Fajula, F.; Galarneau, A. Phospholipid-templated silica nanocapsules as efficient polyenzymatic biocatalysts. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 8511–8520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santema, L.L.; Fraaije, M.W. Activity assays for flavoprotein oxidases: An overview. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garguilo, M.G.; Huynh, N.; Proctor, A.; Michael, A.C. Amperometric sensors for peroxide, choline, and acetylcholine based on electron transfer between horseradish peroxidase and a redox polymer. Anal. Chem. 1993, 65, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shen, G.; Yu, R. Bienzymatic amperometric biosensor for choline based on mediator thionine in situ electropolymerized within a carbon paste electrode. Anal. Biochem. 2004, 334, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razola, S.S.; Pochet, S.; Grosfils, K.; Kauffmann, J.M. Amperometric determination of choline released from rat submandibular gland acinar cells using a choline oxidase biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2003, 18, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Asiri, A.M. Selective choline biosensors based on choline oxidase co-immobilized into self-assembled monolayers on micro-chips at low potential. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 9426–9434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, S.; Ghourchian, H.; Rafiee-Pour, H.-A.; Rahimi, P. Accelerating the electron transfer of choline oxidase using ionic-liquid/NH-MWCNTs nano-composite. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2012, 9, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, R.; Koyuncu, E.; Arslan, H.; Arslan, F. Development of choline biosensor using toluidine blue O as mediator. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 50, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri, V.; Banaei, A. A novel choline biosensor based on immobilization of enzyme choline oxidase on the β-ga2o3 nanowires modified working electrode. Anal. Bioanal. Electrochem. 2020, 12, 663–687. [Google Scholar]

- Kucherenko, D.Y.; Kucherenko, I.S.; Soldatkin, O.O.; Topolnikova, Y.V.; Dzyadevych, S.V.; Soldatkin, A.P. A highly selective amperometric biosensor array for the simultaneous determination of glutamate, glucose, choline, acetylcholine, lactate and pyruvate. Bioelectrochemistry 2019, 128, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tvorynska, S.; Barek, J.; Josypčuk, B. Amperometric Biosensor Based on Enzymatic Reactor for Choline Determination in Flow Systems. Electroanalysis 2019, 31, 1901–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadda, G. pH and deuterium kinetic isotope effects studies on the oxidation of choline to betaine-aldehyde catalyzed by choline oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1650, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmat, A.; Saboury, A.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.; Ghourchian, H.; Ahmad, F. Effects of pH on the activity and structure of choline oxidase from Alcaligenes species. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2008, 55, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M.; Arslan, F.; Arslan, H. An amperometric biosensor for choline determination prepared from choline oxidase immobilized in polypyrrole-polyvinylsulfonate film. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Biotechnol. 2012, 40, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M.; Arslan, H. Choline-sensing carbon paste electrode containing polyaniline (pani)–silicon dioxide composite-modified choline oxidase. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2014, 42, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, M.A.l.; Oliveira, J.C.; Saraiva, J.A. Influence of pH on the Thermal Inactivation Kinetics of Horseradish Peroxidase in Aqueous Solution. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 33, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Alcazar, R.; Bendix, S.; Groth, T.; Ferrer, G.G. Research Progress in Enzymatically Cross-Linked Hydrogels as Injectable Systems for Bioprinting and Tissue Engineering. Gels 2023, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, N.C. Horseradish peroxidase: A modern view of a classic enzyme. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampurdanés, J.; Crespo, G.A.; Maroto, A.; Sarmentero, M.A.; Ballester, P.; Rius, F.X. Determination of choline and derivatives with a solid-contact ion-selective electrode based on octaamide cavitand and carbon nanotubes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 25, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Rahman, M.K.; Mazzone, G.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Sicilia, E.; Shoeib, T. Novel choline selective electrochemical membrane sensor with application in milk powders and infant formulas. Talanta 2021, 221, 121409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Zou, H.; Wu, Z.; Luo, Z.; Li, G. Protoporphyrin IX Based All-Solid-State Ion-Selective Electrodes for Choline Determination In Vitro. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, Y.; Ono, T.; Sato, F.; Kumano, M.; Yoshida, K.; Dairaku, T.; Sasano, Y.; Iwabuchi, Y.; Sato, K. Electrochemical determination of choline using nortropine-N-oxyl for a non-enzymatic system. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2020, 27, 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergoat, L.; Piro, B.; Simon, D.T.; Pham, M.-C.; Noël, V.; Berggren, M. Detection of Glutamate and Acetylcholine with Organic Electrochemical Transistors Based on Conducting Polymer/Platinum Nanoparticle Composites. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 5658–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torriero, A.A.J.; Fitz, M.J.; Mruthunjaya, A.K.V. Calibration-free disposable electrochemical sensor with co-facing electrodes for viscosity monitoring of plasma samples. Talanta 2025, 285, 127290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueland, P.M. Choline and betaine in health and disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Matrix | Typical Concentration (µM) 1 | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | plasma | 8–20 | Fasting adults; rises during pregnancy due to increased phosphatidylcholine turnover | [1,2,3,4,10] |

| milk | 700–1400 | Total choline expressed as free-choline equivalents; water-soluble forms comprise about eighty to ninety percent and vary with lactation stage | [11,12] | |

| CSF | 1–3 | Lumbar CSF in healthy adults; HPLC and enzymatic studies report about two micromolar with age-related variation | [13,14,15] | |

| Rat | plasma | 11 | Untreated Wistar rats | [16] |

| CSF | 7 | |||

| ECS | 3–12 | Basal cortex extracellular space measured in vivo; varies with brain region, probe design and anaesthesia | [17,18,19] | |

| Bovine | plasma | 8–16 | Diet and lactation stage dependent; relevant for metabolic and nutritional studies | [20,21,22] |

| milk | 500–900 | Total choline (sum of free, glycerophosphocholine, and phosphatidylcholine); diet-dependent composition | ||

| Canine | plasma | 6–10 | Healthy adult dogs. It increases to ca. 15 µM when fed commercial diets | [23,24] |

| Sample/Matrix | Electrode/System | Potential (V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl) 1 | Linear Range (µM) | LoD (µM) | Additional Info | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat frontal cortex (in vivo) | 4-channel ceramic MEA; ChOx vs. sentinel | +0.7 | 0.7–80 | 0.2 | Self-referencing subtraction; improved selectivity | [33] |

| 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7 | Pt/ChOx | +0.7 | 0.7–1000 | 0.7 | Enhanced H2O2 oxidation; moderate interferent control | [37] |

| 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 | ChOx-EACC-PB/Pt | 0.0 | 0.5–100 | 0.5 | Low-potential PB transducer; fast response and high sensitivity | [45] |

| ChOx-PB-BL WCNT-IL/GC | −0.05 | 0.5–100 | 0.5 | Fast response; high stability; interferent rejection | [46] | |

| ChOx-MWCNT/Pt | +0.17 | 5–100 | 0.1 | CNT electrocatalysis lowers working bias and improves selectivity | [47] | |

| 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 8 | ChOx-PVA-AuNr/Pt | +0.4 | 20–400 | 10 | Au nanorods markedly enhance conductivity and current response | [48] |

| 0.2 M PBS pH 7.0 | ChOx/IL-NH2-MWCNT/GC | −0.45 | 5–800 | 3.9 | Hydrophilic ILs give highest stability, sensitivity and widest range | [49] |

| 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4 | ChOx-PB/SPCE | −0.05 2 | 0.5–100 | 0.5 | Long-term stability; low-potential detection | [50] |

| 0.1 M PBS pH 7.6 | ChOx/MWCNT-AuNP-PDDA/Pt | +0.36 | 1–500 | 0.3 | CNT-AuNP synergy boosts sensitivity and lowers working bias | [51] |

| 0.1 M PBS pH 7.8 | ChOx/ZnO-MWCNT-PDDA/PG | +0.6 | 1–800 | 0.3 | Synergistic ZnO-CNT film gives high sensitivity and long-term stability | [52] |

| 0.1 M PBS pH 8 | ChOx-PDDA-PB-FePO4/GC | −0.08 | 2–3000 | 0.4 | PB low-potential H2O2 reduction; strong interferent rejection | [53] |

| 0.1 M PBS pH 8.5 | ChOx/AuNP/MWCNT/GCE | −0.3 | 3.3–120 | 0.6 | Mixed CNT-AuNP layer gives high sensitivity and improved one-month stability | [54] |

| Sample or Matrix | Electrode or System | Applied Potential (V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl) 1 | Linear Range (µM) | LoD (µM) | Mediator Between HRP and Electrode | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS pH 7.4 | ChOx-HRP-PVP-Os(bpy)2 Cl/GC | −0.13 | 1–100 | – | PVP-Os(bpy)2Cl | Classic wired HRP stack operated at low bias with fast response of about 2 s | [81] |

| 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4 | ChOx-HRP-Fc-CRGO/GC | −0.13 | 1–400 | 0.4 | Ferrocene-CRGO nanohybrid | Fast, low-bias response; 95% signal in 8 s | [59] |

| 1/15 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 | ChOx-HRP-PTH/CPE | −0.23 | 5–600 | 3 | PTH redox film | PTH shows efficient electron transfer with HRP at negative bias; CPE reproducibility issues | [82] |

| 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 | ChOx-HRP-poly-TTCA/GC | −0.19 | 1–80 | 0.1 | Conducting poly-TTCA film | Cathodic detection of peroxide on poly-TTCA supports low-potential operation | [76] |

| ChOx-HRP/CPE | 0 | 0.05–70 | 0.01 | Phenothiazine | Low-bias reduction; stable mediated HRP transduction; CPE reproducibility issues | [83] | |

| 0.1 M Tris buffer pH 8 | ChOx-HRP-PDDA-MWCNT/GC | −0.20 | 50–5000 | 10 | None added, CNT surface provides electrocatalysis and possible direct wiring of HRP | Authors note possible direct reduction of peroxide at CNT at low potential | [78] |

| 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.5 | ChOx-HRP- PVI13-dmeOs/CPE | −0.13 | 1–10 | 0.1 | PVI13-dmeOs redox polymer | Early example of low-potential wired HRP for peroxide reduction in choline sensors; CPE reproducibility issues | [74] |

| infant formula | HRP-ChOx-CNF MnO2-PMG/SPCE | −0.20 2 | 4–9000 | 0.8 | PMG | Improved stability and low-bias H2O2 transduction | [73] |

| Feature | First Generation (H2O2 Readout) | MET | Bienzymatic (ChOx-HRP) | Purported DET |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal oxidant | O2 | Mediator | Mediator via HRP | Electrode (claimed) |

| Operating potential | High positive | Low bias (mediator-defined) | Low bias | Variable, typically positive |

| O2 dependence | Strong | Present unless mediator dominates | Strong (ChOx-limited) | None (if genuine) |

| Stoichiometry | 1–2 H2O2 per choline | 2–4 e− depending on mediation | 2 mediator equivalents per H2O2 * | Unverified |

| Failure modes | Interferents, O2 limitation | Mediator leaching, incomplete mediation | HRP instability | Redox-film artefacts |

| Matrix compatibility | Moderate-low | Moderate-high | High | Unverified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Torriero, A.A.J.; Thiak, S.M.; Mruthunjaya, A.K.V. Electrochemical Choline Sensing: Biological Context, Electron Transfer Pathways and Practical Design Strategies. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010023

Torriero AAJ, Thiak SM, Mruthunjaya AKV. Electrochemical Choline Sensing: Biological Context, Electron Transfer Pathways and Practical Design Strategies. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorriero, Angel A. J., Sarah M. Thiak, and Ashwin K. V. Mruthunjaya. 2026. "Electrochemical Choline Sensing: Biological Context, Electron Transfer Pathways and Practical Design Strategies" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010023

APA StyleTorriero, A. A. J., Thiak, S. M., & Mruthunjaya, A. K. V. (2026). Electrochemical Choline Sensing: Biological Context, Electron Transfer Pathways and Practical Design Strategies. Biomolecules, 16(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010023