Integrated Analysis of ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq Reveals the Signal Transduction Regulation of the Molting Cycle in the Muscle of Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sampling

2.1.1. Experimental Animals and Culture Environment

2.1.2. Muscle Sample Collection During the Molt Period (Period E)

2.2. Sequencing

2.2.1. ATAC-Seq Sequencing

2.2.2. RNA-Seq Sequencing

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. ATAC-Seq Data Analysis

2.3.2. RNA-Seq Data Analysis

2.3.3. Integrated Analysis

2.4. Structural Analysis of Candidate GPCRs

2.5. Gene Expression Verification

3. Results

3.1. ATAC-Seq Analysis of Chromatin Accessibility in Different Molting Stages

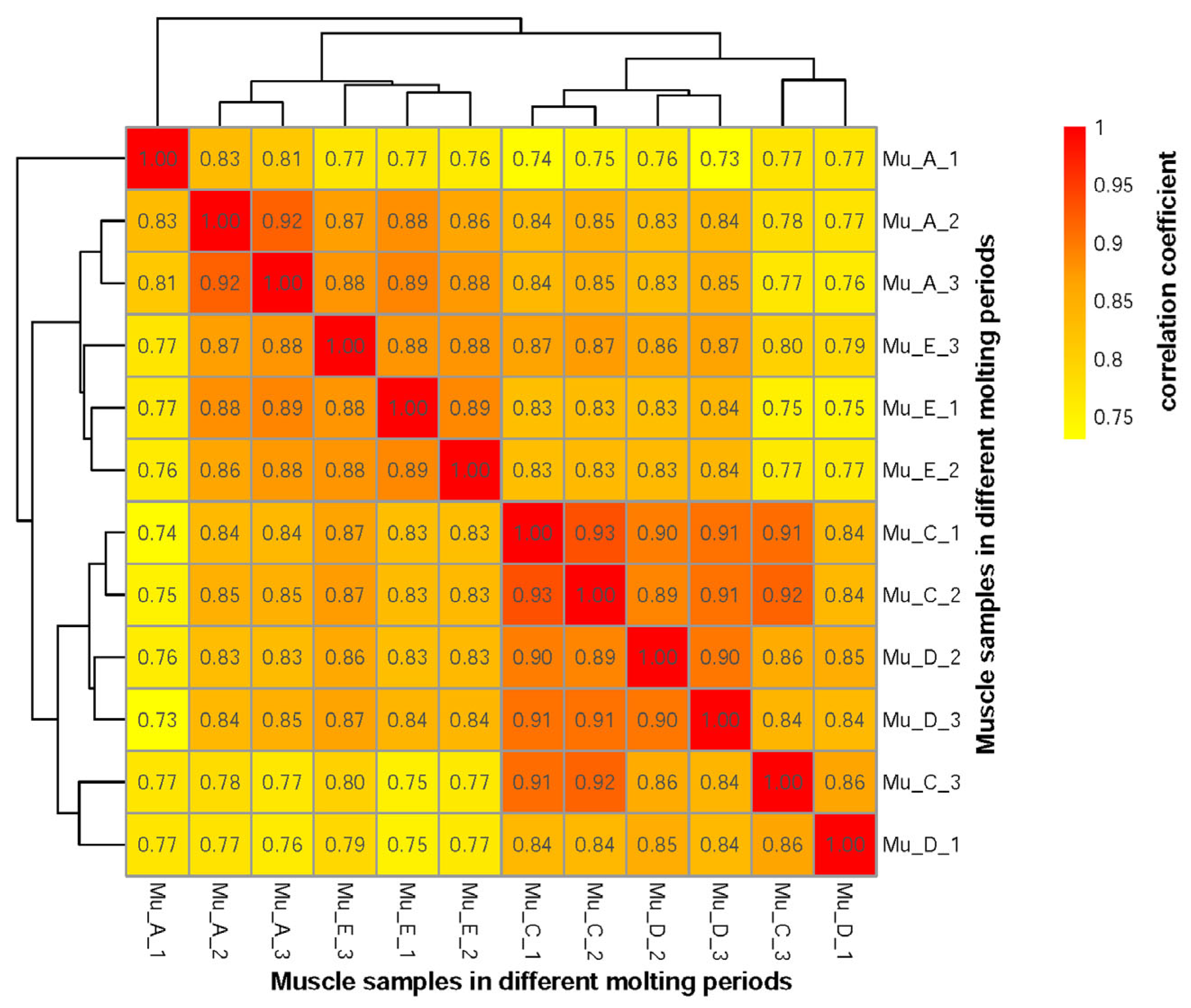

3.2. RNA-Seq Analysis of Gene Expression in Different Molting Stages

3.3. Integration of ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq for IDEG Analysis

3.4. Signaling Pathway Analysis of IDEGs

3.5. Structural Analysis of Candidate GPCR Genes

3.6. RT-qPCR Verification of GPCR Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mykles, D.L. Molting in crustaceans: A complex regulatory process. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 674711. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, X.; Tian, Z.; Wu, J.; Mu, S. Molt stages and digestive enzyme activity in Eriocheir sinensis. J. Fish. China 2012, 19, 806–812. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.S.; Mykles, D.L. Regulation of crustacean molting. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 172, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Hou, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Physiological and gene expression profiles of leg muscle provide insights into molting-dependent growth of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Reprod. Breed. 2021, 1, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Lv, L.; Gou, Y.; Wang, B.; Hao, T. Integration of ATAC-seq and RNA-seq identifies active G-protein coupled receptors functioning in molting process in muscle of Eriocheir sinensis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 900160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, A.; Song, Z.; He, Z.; Sun, J. Integration of ATAC-seq and RNA-seq reveals signal regulation during post-molt and inter-molt stages in muscle of Eriocheir sinensis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 1529684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.G.; SHEN, C.; Yao, Q.Q.; Zeng, Q.T.; Liu, Q.B.; Cheng, Y.Q. The full length cDNA cloning and expression analysis of EcR from the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). J. Fish. China 2014, 38, 651–661. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.G.; Guo, Z.H.; Yao, Q.Q. The full length cDNA cloning and expression analysis of RXR from the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). J. Fish. China 2013, 37, 1761–1769. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.Q.; Yang, Z.G.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.H.; Liu, Q.B.; Shi, Q.Y.; Cheng, Y.X. Full length cDNA cloning of the chitinase gene (HXchit) and analysis of expression during the molting cycle of the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. J. Fish. Sci. 2015, 2, 185–195. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wu, X.G.; Xu, L.; Yao, Q.Q.; Cheng, Y.X. Expression analysis of Myostatin during molting cycle in Eriocheir sinensis. J. Shanghai Ocean Univ. 2015, 5, 662–667. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. RNA interference of mTOR gene delays molting process in Eriocheir sinensis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 256, 110651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Yue, W.; Chen, J.; Gaughan, S.; Lu, W.; Lu, G.; Wang, C. Transcriptomic variation of hepatopancreas reveals the energy metabolism and biological processes associated with molting in Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Jiao, C. Molt-dependent transcriptome analysis of claw muscles in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Genes Genom. 2019, 41, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, J.; Dong, X.; Geng, X.; Qiu, G. Transcriptomic analysis of gills provides insights into the molecular basis of molting in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). PeerJ 2019, 7, e7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro, J.D.; Wu, B.; Chang, H.Y.; Greenleaf, W.J. ATAC-seq: A method for assaying chromatin accessibility genome-wide. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2015, 109, 21.29.1–21.29.9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Multi-omics integration identifies key regulatory networks during crustacean molting. Aquac. Res. 2023, 54, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Corces, M.R.; Trevino, A.E.; Hamilton, E.G.; Greenside, P.G.; Sinnott-Armstrong, N.A.; Vesuna, S.; Satpathy, A.T.; Rubin, A.J.; Montine, K.S.; Wu, B.; et al. An improved ATAC-seq protocol reduces background and enables interrogation of frozen tissues. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Lei, R.; Ding, S.W.; Zhu, S. Skewer: A fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinf 2014, 15, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, F.; Dundar, F.; Diehl, S.; Gruning, B.A.; Manke, T. deepTools: A flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W187–W191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Meyer, C.A.; Eeckhoute, J.; Johnson, D.S.; Bernstein, B.E.; Nusbaum, C.; Myers, R.M.; Brown, M.; Li, W.; et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 2008, 9, R137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; He, Q.Y. ChIPseeker: An R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2382–2383. [Google Scholar]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Soil 2020, 5, 47–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, M.; Bermel, W.; Spencer, A.; Dobson, C.M.; Smith, L.J.; Schwalbe, H. Side-chain conformations in an unfolded protein: χ1 distributions in denatured hen lysozyme determined by heteronuclear 13C, 15N NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 288, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschaikner, P.M.; Regele, D.; Rock, R.; Salvenmoser, W.; Meyer, D.; Bouvier, M.; Geley, S.; Stefan, E.; Aanstad, P. Feedback control of the Gpr161-G(alphas)-PKA axis contributes to basal Hedgehog repression in zebrafish. Development 2021, 148, dev192443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Somatilaka, B.N.; White, K.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Ciliary and extraciliary Gpr161 pools repress hedgehog signaling in a tissue-specific manner. eLife 2021, 10, e67121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ranjan, R.; Dawson-Scully, K.; Bronk, P.; Marin, L.; Seroude, L.; Lin, Y.-J.; Nie, Z.; Atwood, H.L.; Benzer, S.; et al. Presynaptic regulation by the GPCR methuselah in Drosophila. Neuron 2002, 36, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.F. G protein-coupled receptors function as cell membrane receptors for the steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, W.L.; Cai, M.J.; Wang, J.X.; Zhao, X.F. G-protein-coupled receptor controls steroid hormone signaling in cell membrane. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, N.; Harrison, S.; Hwang, S.H.; Chen, Z.; Karelina, M.; Deshpande, I.; Suomivuori, C.M.; Palicharla, V.R.; Berry, S.P.; Tschaikner, P.; et al. GPR161 structure uncovers the redundant role of sterol-regulated ciliary cAMP signaling in the Hedgehog pathway. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2024, 31, 667–677. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, P.; Trivedi, D.; Hasan, G. FMRFa receptor stimulated Ca2+ signals alter the activity of flight modulating central dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007459. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Li, B. Species-specific duplicated FMRFaR-like gene A62 regulates spontaneous locomotion in Apolygus lucorum. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 3358–3368. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.W.; Chu, P.Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Chan, W.R.; Wang, Y.H. Identification of functional SSR markers in freshwater ornamental shrimps Neocaridina denticulata using transcriptome sequencing. Mar. Biotechnol. 2020, 22, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, G.A.; Niswender, C.M. GRM7 gene mutations and consequences for neurodevelopment. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2023, 225, 173546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wu, T.; Zhao, F.; Lau, A.; Birch, C.M.; Zhang, D.D. KPNA6 (Importin alpha7)-mediated nuclear import of Keap1 represses the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31, 1800–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Q.; Fang, T.; Yu, L.X.; Lv, G.S.; Lv, H.W.; Liang, D.; Li, T.; Wang, C.Z.; Tan, Y.X.; Ding, J.; et al. ADRB2 signaling promotes HCC progression and sorafenib resistance by inhibiting autophagic degradation of HIF1alpha. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulik, G. ADRB2-Targeting Therapies for Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, F.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Tao, J.; Gu, Y.; Li, H.; Yi, X.; Gong, J.; You, D.; Feng, Z.; et al. Cortistatin protects against septic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting cardiomyocyte pyroptosis through the SSTR2-AMPK-NLRP3 pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 134, 112186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Clean Reads | Clean Ratio | Q20 | Q30 | Mapped Reads 1 | Peak | Summits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mu_E_1 | 43,217,675 | 67.5% | 93.8% | 86.0% | 36,107,288 (83.6%) | 52,473 | 68,956 |

| Mu_E_2 | 41,023,204 | 61.9% | 95.3% | 89.3% | 24,335,132 (59.3%) | 44,610 | 56,607 |

| Mu_E_3 | 43,139,257 | 68.3% | 94.2% | 87.3% | 35,556,488 (82.4%) | 49,831 | 68,351 |

| Sample | Clean Reads | Clean Ratio | Q20 | Q30 | Mapped Reads 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mu_E_1 | 28,862,970 | 96.7% | 96.3 | 91.4 | 23,908,337 (82.8%) |

| Mu_E_2 | 30,411,926 | 97.3% | 96.3 | 91.5 | 25,329,334 (83.3%) |

| Mu_E_3 | 30,257,948 | 95.9% | 96.4 | 91.6 | 24,617,362 (81.4%) |

| Molting Stage | IDEGs | Up-Regulated IDEGs | Down-Regulated IDEGs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mu_C vs. Mu_D | 17 | 12 | 5 |

| Mu_D vs. Mu_E | 491 | 327 | 164 |

| Mu_E vs. Mu_A | 84 | 60 | 24 |

| Mu_A vs. Mu_C | 491 | 40 | 451 |

| Stage | Code | Gene ID | Gene Name | TMHMM 1 | PSIPRED 2 | SWISS-MODEL 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mu_A vs. Mu_C | U244 | evm.TU.CM024127.1.244 | FMRFaR | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| U116 | evm.TU.CM024146.1.116 | GRM7 | 7 | 7 | 7× 2 | |

| U176 | evm.TU.CM024164.1.176 | gpr161 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| U314 | evm.TU.CM024134.1.314 | mth2 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| U415 | evm.TU.CM024100.1.415 | moody | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| Mu_D vs. Mu_E | U176 | evm.TU.CM024164.1.176 | gpr161 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| U63 | evm.TU.CM024137.1.63 | Kpna6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| U210 | evm.TU.CM024165.1.210 | ADRB2 | 8 | 7 | 7 | |

| U244 | evm.TU.CM024127.1.244 | FMRFaR | 6 | 7 | 7 | |

| U288 | evm.TU.CM024152.1.288 | SSTR2 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| U276 | evm.TU.CM024144.1.276 | rhodopsin-like | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| U157 | evm.TU.CM024104.1.157 | HTR4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | |

| Mu_E vs. Mu_A | U314 | evm.TU.CM024134.1.314 | mth2 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| U66 | evm.TU.CM024136.1.65_evm.TU.CM024136.1.66 | sky | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| Code | Gene ID | Gene Name | Stage | Log2FoldChange | Duplicated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U116 | evm.TU.CM024146.1.116 | GRM7 | Mu_A vs. Mu_C | −7.62 | NA |

| U415 | evm.TU.CM024100.1.415 | moody | Mu_A vs. Mu_C | 1.97 | NA |

| U63 | evm.TU.CM024137.1.63 | Kpna6 | Mu_D vs. Mu_E | 3.22 | NA |

| U210 | evm.TU.CM024165.1.210 | ADRB2 | Mu_D vs. Mu_E | 4.53 | NA |

| U288 | evm.TU.CM024152.1.288 | SSTR2 | Mu_D vs. Mu_E | 2.06 | NA |

| U176 | evm.TU.CM024164.1.176 | gpr161 | Mu_A vs. Mu_C | −1.78 | duplicated in two stages |

| Mu_D vs. Mu_E | 2.07 | ||||

| U244 | evm.TU.CM024127.1.244 | FMRFaR | Mu_A vs. Mu_C | −3.99 | duplicated in two stages |

| Mu_D vs. Mu_E | 2.96 | ||||

| U314 | evm.TU.CM024134.1.314 | mth2 | Mu_A vs. Mu_C | −2.14 | duplicated in two stages |

| Mu_E vs. Mu_A | 1.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Tan, R.; Sun, J.; Wang, B.; Hao, T. Integrated Analysis of ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq Reveals the Signal Transduction Regulation of the Molting Cycle in the Muscle of Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Biomolecules 2026, 16, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010108

He Z, Li J, Zhang J, Zhang R, Tan R, Sun J, Wang B, Hao T. Integrated Analysis of ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq Reveals the Signal Transduction Regulation of the Molting Cycle in the Muscle of Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhen, Jingjing Li, Jingjing Zhang, Ruiqi Zhang, Rongkang Tan, Jinsheng Sun, Bin Wang, and Tong Hao. 2026. "Integrated Analysis of ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq Reveals the Signal Transduction Regulation of the Molting Cycle in the Muscle of Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis)" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010108

APA StyleHe, Z., Li, J., Zhang, J., Zhang, R., Tan, R., Sun, J., Wang, B., & Hao, T. (2026). Integrated Analysis of ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq Reveals the Signal Transduction Regulation of the Molting Cycle in the Muscle of Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Biomolecules, 16(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010108