The Utility of Maternal Blood S100B in Women with Suspected or Established Preeclampsia—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

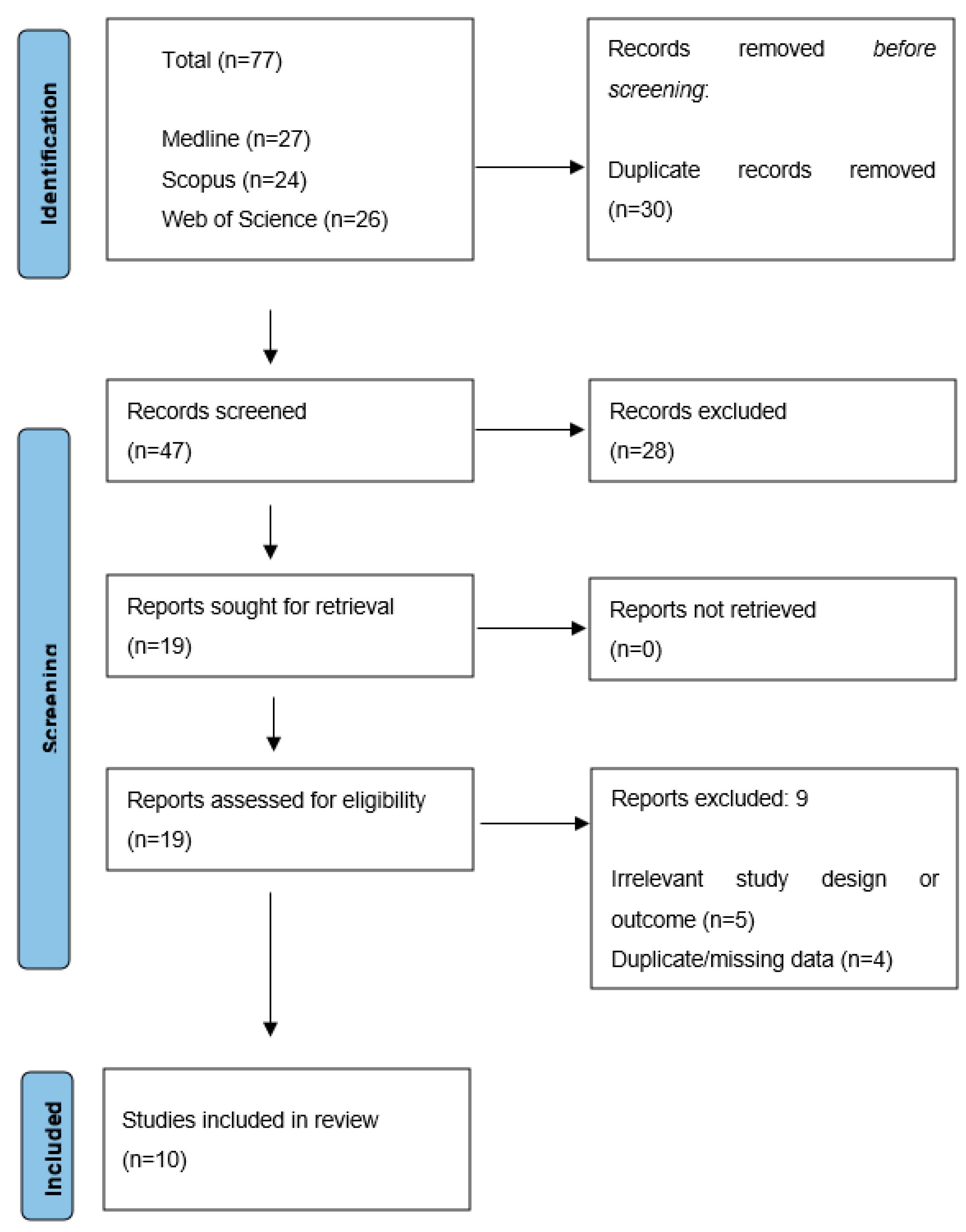

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

- (1)

- Participants: Pregnancies complicated by PE and/or ECL and appropriate controls.

- (2)

- Intervention: Measurement of maternal serum or plasma S100B levels at any stage of pregnancy or postpartum.

- (3)

- Comparator: Levels of S100B in the serum or plasma of controls.

- (4)

- Outcome: Development, severity, or complications related to PE and ECL.

- (5)

- Study designs: Case series or prospective–retrospective case–control studies.

2.3. Primary Outcomes

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Search Results

2.6. Study Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

2.7. Characteristics of the Included Studies

2.7.1. General Characteristics

2.7.2. Clinical Manifestations of Severe PE

2.7.3. Laboratory Parameters, Blood Levels, Predictive Value of S100B, and Summary of Conclusions

2.7.4. S100B Initial Detection

2.7.5. S100B During Pregnancy

2.7.6. S100B as a Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker

2.7.7. Postpartum S100B Levels

2.7.8. S100B’s Origin During Pregnancy

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study Source | Study Type | NOS Score | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schmidt, A. P., et al. (2004) [44] | Case–Control Study | 7/8 | The study has strong participant criteria, thorough data collection, and robust stats, but limitations include blinding and controlling for potential confounders. |

| Vettorazzi, J., et al. (2012) [45] | Case–Control Study | 8/9 | Reasonable methodology in participant selection, group comparability, and outcome assessment, but enhancing representativeness and addressing key confounding factors would add value. |

| Wikstrom, A. K., et al. (2012) [46] | Observational Longitudinal Nested Case–Control Study | 9/9 | High methodological quality in participant selection, comparability, exposure, and outcome assessment. A larger sample could enhance the results’ robustness and generalizability. |

| Bergman L., et al. (2014) [47] | Cross-Sectional Case–Control Study | 8/9 | Meets the NOS criteria for group selection, comparability, and exposure/outcome assessment effectively, but potential confounding factors remain. |

| Artunc-Ulkumen B., et al. (2015) [48] | Prospective Case–Control Study | 7/9 | The study addresses the NOS criteria regarding participant selection and exposure/outcome measurement, but potential bias in control recruitment and unaddressed confounding factors are concerns. |

| Bergman L., et al. (2016) [49] | Longitudinal Case–Control Study | 8/9 | High quality of study design, methodology, and reporting. Lack of blinding. |

| Wu, J., et al. (2021) [50] | Case–Control Study | 6/9 | Moderate quality, unclear control ascertainment, and small sample size. |

| Andersson M., et al. (2021) [51] | Case–Control Study | 8/9 | The study effectively meets the NOS criteria for group selection and exposure/outcome assessment but lacks detail on controlling for confounding variables. |

| Busse, M., et al. (2022) [38] | Cross-Sectional Case–Control Study | 6/9 | Clear criteria, diverse biomarkers, and S100B–immune cell correlations explored. Limitations: small sample, bias, incomplete data, long storage, and no multiple comparison adjustments, affecting validity. |

| Friis, T., et al. (2022) [52] | Observational Case–control study | 7/9 | The study shows strong design and methodology, but considerable limitations in sample size and potential confounders when interpreting the findings. |

References

- Magee, L.A.; Brown, M.A.; Hall, D.R.; Gupte, S.; Hennessy, A.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Kenny, L.C.; McCarthy, F.; Myers, J.; Poon, L.C.; et al. The 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022, 27, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poon, L.C.; Shennan, A.; Hyett, J.A.; Kapur, A.; Hadar, E.; Divakar, H.; McAuliffe, F.; da Silva Costa, F.; von Dadelszen, P.; McIntyre, H.D.; et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on pre-eclampsia: A pragmatic guide for first-trimester screening and prevention. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019, 145 (Suppl. 1), 1–33, Erratum in Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019, 146, 390–391.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittara, T.; Vyrides, A.; Lamnisos, D.; Giannakou, K. Preeclampsia and long-term health outcomes for mother and infant: An umbrella review. BJOG 2021, 128, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajantie, E.; Eriksson, J.G.; Osmond, C.; Thornburg, K.; Barker, D.J. Pre-eclampsia is associated with increased risk of stroke in the adult offspring: The Helsinki birth cohort study. Stroke 2009, 40, 1176–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funai, E.F.; Friedlander, Y.; Paltiel, O.; Tiram, E.; Xue, X.; Deutsch, L.; Harlap, S. Long-term mortality after preeclampsia. Epidemiology 2005, 16, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, L.; Masoumi, Z.; Hansson, L.R.; Hansson, S.R. The roles of free iron, heme, haemoglobin, and the scavenger proteins haemopexin and alpha-1-microglobulin in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 952–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, L.; Ducat, A.; Castille, J.; Zia, I.; Kalapotharakos, G.; Hedström, E.; Vilotte, J.L.; Vaiman DHansson, S.R. Alpha-1 microglobulin as a potential therapeutic candidate for treatment of hypertension and oxidative stress in the STOX1 preeclampsia mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampas, G.A.; Eleftheriades, M.I.; Panoulis, K.C.; Rizou, M.D.; Haliassos, A.D.; Metallinou, D.K.; Mastorakos, G.P.; Rizos, D.A. Prediction of pre-eclampsia combining NGAL and other biochemical markers with Doppler in the first and/or second trimester of pregnancy. A pilot study. Eur. J. Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 205, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, D.; Eleftheriades, M.; Karampas, G.; Rizou, M.; Haliassos, A.; Hassiakos, D.; Vitoratos, N. Placental growth factor and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 are useful markers for the prediction of preeclampsia but not for small for gestational age neonates: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 171, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, D.L.; Wright, D.; Poon, L.C.Y.; Syngelaki, A.; O’Gorman, N.; de Paco Matallana, C.; Akolekar, R.; Cicero, S.; Janga, D.; Singh, M.; et al. ASPRE trial: Performance of screening for preterm pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 50, 492–495, Erratum in Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 50, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, D.L.; Wright, D.; Poon, L.C.; O’Gorman, N.; Syngelaki, A.; de Paco Matallana, C.; Akolekar, R.; Cicero, S.; Janga, D.; Singh, M.; et al. Aspirin versus Placebo in Pregnancies at High Risk for Preterm Preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudero, C.; Kupka, E.; Ibañez, B.; Sandoval, H.; Troncoso, F.; Wikström, A.K.; López-Espíndola, D.; Acurio, J.; Torres-Vergara, P.; Bergman, L. Brain Vascular Dysfunction in Mothers and Their Children Exposed to Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2023, 80, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, S.T.; Ryan, M.J. Pathophysiology of cerebral vascular dysfunction in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2019, 21, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishel Bartal, M.; Sibai, B.M. Eclampsia in the 21st century. Am. J. Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S1237–S1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, J.L.; Ordi, J.; Carrilho, C.; Ismail, M.R.; Zsengeller, Z.K.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Rosen, S. The pathology of eclampsia: An autopsy series. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2017, 36, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, J.E.; Rabinstein, A.A. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Vargas, M.; Striano, P.; Del Guercio, L.; Buonanno, P.; Servillo, G. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: The endothelial hypotheses. Med. Hypotheses 2014, 82, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Matsushima, M.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Wachi, Y.; Izawa, T.; Sakai, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Iwashita, M. Antepartum reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome with pre-eclampsia and reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy. J. Obs. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2015, 41, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, C.; McCullough, L.D.; Awad, I.A.; Chireau, M.V.; Fedder, W.N.; Furie, K.L.; Howard, V.J.; Lichtman, J.H.; Lisabeth, L.D.; Piña, I.L.; et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014, 45, 1545–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Milic, N.M.; Weissgerber, T.L.; White, W.M.; Kantarci, K.; Mosley, T.H.; Windham, B.G.; Simpson, B.N.; Turner, S.T.; Garovic, V.D. Impaired cognition and brain atrophy decades after hypertensive pregnancy disorders. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2016, 9 (Suppl. 1), S70–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolf, E.G.; Sydsjö, G.C.; Bladh, M.K.; Berg, G.; Sharma, S. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and later dementia: A Swedish National Register Study. Acta Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basit, S.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Boyd, H.A. Pre-eclampsia and risk of dementia later in life: Nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2018, 363, k4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irgens, H.U.; Reisaeter, L.; Irgens, L.M.; Lie, R.T. Long term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2001, 323, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, L.; Torres-Vergara, P.; Penny, J.; Wikström, J.; Nelander, M.; Leon, J.; Tolcher, M.; Roberts, J.M.; Wikström, A.K.; Escudero, C. Investigating maternal brain alterations in preeclampsia: The need for a multidisciplinary effort. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2019, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukes, A.M.; De Groot, J.C.; Wiegman, M.J.; Aarnoudse, J.G.; Sanwikarja GSZeeman, G.G. Long-term cerebral imaging after pre-eclampsia. BJOG 2012, 119, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegman, M.J.; Zeeman, G.G.; Aukes, A.M.; Bolte, A.C.; Faas, M.M.; Aarnoudse, J.G.; de Groot, J.C. Regional distribution of cerebral white matter lesions years after preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, T.; Boardman, H.; Bilderbeck, A.; Griffanti, L.; Kenworthy, Y.; Zwager, C.; McKean, D.; Francis, J.; Neubauer, S.; Yu, G.Z.; et al. Long-term cerebral white and gray matter changes after preeclampsia. Neurology 2017, 88, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oatridge, A.; Holdcroft, A.; Saeed, N.; Hajnal, J.V.; Puri, B.K.; Fusi, L.; Bydder, G.M. Change in brain size during and after pregnancy: Study in healthy women and women with preeclampsia. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, N.; Kaur, A.; Elharram, M.; Rossi, A.M.; Pilote, L. Impact of preeclampsia on long-term cognitive function. Hypertension 2018, 72, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharram, M.; Dayan, N.; Kaur, A.; Landry, T.; Pilote, L. Long-term cognitive impairment after preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholefield, B.R.; Tijssen, J.; Ganesan, S.L.; Kool, M.; Couto, T.B.; Topjian, A.; Atkins, D.L.; Acworth, J.; McDevitt, W.; Laughlin, S.; et al. Prediction of good neurological outcome after return of circulation following paediatric cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2024, 30, 110483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metallinou, D.; Karampas, G.; Nyktari, G.; Iacovidou, N.; Lykeridou, K.; Rizos, D. S100B as a biomarker of brain injury in premature neonates. A prospective case—Control longitudinal study. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 510, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurewicz, E.; Filipek, A. Ca2+-binding proteins of the S100 family in preeclampsia. Placenta 2022, 127, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michetti, F.; Clementi, M.E.; Di Liddo, R.; Valeriani, F.; Ria, F.; Rende, M.; Di Sante, G.; Romano Spica, V. The S100B Protein: A Multifaceted Pathogenic Factor More Than a Biomarker. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrais, A.C.; Melo, L.H.M.F.; Norrara, B.; Almeida, M.A.B.; Freire, K.F.; Melo, A.M.M.F.; Oliveira, L.C.; Lima, F.O.V.; Engelberth, R.C.G.J.; Cavalcante, J.S.; et al. S100B protein: General characteristics and pathophysiological implications in the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Neurosci. 2022, 132, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michetti, F.; D’Ambrosi, N.; Toesca, A.; Puglisi, M.A.; Serrano, A.; Marchese, E.; Corvino, V.; Geloso, M.C. The S100B story: From biomarker to active factor in neural injury. J. Neurochem. 2019, 148, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, J.; Bernstein, H.G.; Bielau, H.; Berndt, A.; Brisch, R.; Mawrin, C.; Keilhoff, G.; Bogerts, B. Evidence for a wide extra-astrocytic distribution of S100B in human brain. BMC Neurosci. 2007, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, M.; Scharm, M.; Oettel, A.; Redlich, A.; Costa, S.D.; Zenclussen, A.C. Enhanced S100B expression in T and B lymphocytes in spontaneous preterm birth and preeclampsia. J. Perinat. Med. 2021, 50, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tskitishvili, E.; Komoto, Y.; Temma-Asano, K.; Hayashi, S.; Kinugasa, Y.; Tsubouchi, H.; Song, M.; Kanagawa, T.; Shimoya, K.; Murata, Y. S100B protein expression in the amnion and amniotic fluid in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 12, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Making 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Collaborating Centre for Womens and Childrens Health. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. Hypertension in Pregnancy: The Management of Hypertensive Disorders During Pregnancy; RCOG Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2011. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK294460/bin/appb-fm4.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Schmidt, A.P.; Tort, A.; Amaral, O.B.; Schmidt, A.; Walz, R.; Vettorazzi-Stuckzynski, J.; Martins-Costa, S.H.; Ramos, J.G.; Souza, D.O.; Portela, L.V.C. Serum S100B in Pregnancy-Related Hypertensive Disorders: A Case–Control Study. Clin. Chem. 2004, 50, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vettorazzi, J.; Torres, F.V.; Ávila, T.T.; Martins-Costa, S.H.; Souza, D.O.; Portela, L.V.C.; Ramos, J.G. Serum S100B in pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia: A case-control study Pregnancy. Hypertension 2012, 2, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikström, A.K.; Ekegren, L.; Karlsson, M.; Wikström, J.; Bergenheim, M.; Åkerud, H. Serum Plasma levels of S100B during pregnancy in women developing pre-eclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2012, 2, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, L.; Akhter, T.; Wikström, A.K.; Wikström, J.; Naessen, T.; Åkerud, H. Plasma levels of S100B in preeclampsia and association with possible central nervous system effects. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 27, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artunc-Ulkumen, B.; Guvenc, Y.; Goker, A.; Gozukara, C. Maternal Serum S100-B, PAPP-A and IL-6 levels in severe preeclampsia. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. Obstet. 2015, 292, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, L.; Åkerud, H.; Wikström, A.K.; Larsson, M.; Naessen, T.; Akhter, T. Cerebral Biomarkers in Women With Preeclampsia Are Still Elevated 1 Year Postpartum. Am. J. Hypertens. 2016, 29, 1374–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sheng, X.; Zhou, S.; Fang, C.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Jia, Z.; Jia, X.; You, Y. Clinical significance of S100B protein in pregnant woman with early-onset severe preeclampsia. Ginekol. Pol. 2024, 95, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Oras, J.; Thörn, S.E.; Karlsson, O.; Kälebo, P.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Bergman, L. Signs of neuroaxonal injury in preeclampsia-A case control study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, T.; Wikström, A.K.; Acurio, J.; León, J.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Nelander, M.; Åkerud, H.; Kaihola, H.; Cluver, C.; et al. Cerebral Biomarkers and Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity in Preeclampsia. Cells 2022, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, E.; Rolnik, D.L.; Zhou, W.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Koga, K.; Francisco, R.P.V.; Whitehead, C.; Hyett, J.; da Silva Costa, F.; Nicolaides, K.; et al. Pre-eclampsia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 8, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.H.; Tan, S.S.; Sze, S.K.; Lee, W.K.R.; Ng, M.J.; Lim, S.K. Plasma biomarker discovery in preeclampsia using a novel differential isolation technology for circulating extracellular vesicles. Am. J. Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 211, e1–e13. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, L.; Zetterberg, H.; Kaihola, H.; Hagberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Åkerud, H. Blood-based cerebral biomarkers in preeclampsia: Plasma concentrations of NfL, tau, S100B and NSE during pregnancy in women who later develop preeclampsia—A nested case control study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Source | Reference Number | Year | Study Type | NOS Score | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmidt, A. P., et al. | [44] | 2004 | Case–Control | 7/9 | High |

| Vettorazzi, J., et al. | [45] | 2012 | Case–Control | 8/9 | High |

| Wikström, A. K., et al. | [46] | 2012 | Observational Longitudinal Nested Case–Control | 9/9 | High |

| Bergman L., et al. | [47] | 2014 | Cross-Sectional Case–Control | 8/9 | High |

| Artunc-Ulkumen B., et al. | [48] | 2015 | Prospective Case–Control | 7/9 | High |

| Bergman L., et al. | [49] | 2016 | Longitudinal Case–Control | 8/9 | High |

| Wu, J., et al. | [50] | 2021 | Case–Control | 6/9 | Low |

| Andersson M., et al. | [51] | 2021 | Case–Control | 8/9 | High |

| Friis, T., et al. | [52] | 2022 | Observational Case–Control | 7/9 | High |

| Busse, M., et al. | [38] | 2022 | Cross-Sectional Case–Control | 6/9 | Low |

| Definition | Study Population | Ethnicity | Maternal Age (Years) | BMI (Kg/m2) | Nullipara n (%) | Singleton n (%) | Smoking n (%) | MgSO4 | Delivery (Weeks) | Birth Weight (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmidt, A. P. (2004) [44] | Former | 18 PE | White 83% | 24.8 ± 6.2 | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | - |

| 11 HT | White 82% | 32.4 ± 7.2 | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | ||

| 10 ECL | White 80% | 19.6 ± 6.9 | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | ||

| 16 NP | White 69% | 21.8 ± 4.8 | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | ||

| Vettorazzi, J. (2012) [45] | Former | 15 NP | - | 24.5 ± 7.1 | - | - | - | - | - | 33.7 ± 4.7 | 2504 ± 909 |

| 12 MPE | - | 23.6 ± 7.6 | - | - | - | - | - | 36.7 ± 2.8 | 2975 ± 634 | ||

| 34 SPE (8/34 HELLP) (5/34 ECL) | - | 28.5 ± 9.3 | - | - | - | - | In 8/34 at sampling | 32.2 ± 3.8 | 1830 ± 851 | ||

| Wikström, A. K. (2012) [46] | Former | 37 NP | - | 31 (28–33) | 23 (21–25) | 21 (60) | 37 (100) | 0 | - | 40.5 (40–41) | - |

| 16 PE | - | 29 (26–32) | 24 (22–28) | 13 (83) | 16 (100) | 0 | - | 39.5 (38–41) | - | ||

| Bergman L. (2014) [47] | Former | 53 PE | - | 30 ± 5 | 27 ± 6 | 37 (70) | 53 (100) | 0 (0) | - | 35.7 ± 4.1 | 2554 ± 988 |

| 58 NP | - | 30 ± 4 | 23 ± 3 | 29 (50) | 58 (100) | 2 (3) | - | 40 ± 1.29 | 3658 ± 434 | ||

| Artunc-Ulkumen B. (2015) [48] | Former | 27 SPE (8/27 HELLP) | - | 29.29 ± 4.29 | 30.39 ± 4.63 | - | 27 (100) | - | In all after sampling | 33.6 ± 4.6 | 2140 ± 873 |

| 36 NP | - | 29.69 ± 4.85 | 29.65 ± 4.42 | - | 36 (100) | - | - | 38.5 ± 1.4 | 3405 ± 407 | ||

| Bergman L. (2016) [49] | Former | 54 NP | - | 30 ± 4 | 23 ± 5 | 29 (50) | 54 (100) | 2 (3) | - | 40 ± 1.2 | 3658 ± 434 |

| 48 PE | - | 30 ± 5 | 27 ± 8 | 37 (70) | 48 (100) | 0 (0) | - | 35.7 ± 4.1 | 2554 ± 988 | ||

| Wu, J. (2021) [50] | Revised | 9 early PE | Asian | 35 | 18–25 | 9 (100%) | 9 (100%) | - | - | - | FGR |

| 13 NP | Asian | 35 | 18–25 | 13 (100%) | 13 (100%) | - | - | - | Normal | ||

| Andersson M. (2021) [51] | Revised | 15 SPE | - | 32.5 (5.8) | 27.5 (3.8) | 12 (80) | - | 1(7) | In 3/20 | 34.71 (4.04) | 2200 (991) |

| 15 NP | - | 31.9 (3.7) | 22.9 (3.1) | 5 (33) | - | 1(7) | - | 39.07 (5) | 3430 (327) | ||

| Friis, T. (2022) [52] | Revised (all PE had proteinuria) | 28 PE (16/28 SPE) | - | 28 (25–32) | 26 (23–29) | 23 (82) | - | - | In 0/28 | 35 (25–41) | - |

| 28 NP | - | 33 (29–35) | 24 (22–26) | 10 (36) | - | - | - | 35 (27–38) | - | ||

| 16 non-pregnant | - | 27 (24–36) | 22 (20–25) | 9 (56%) | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Busse, M. (2022) [38] | Revised | 17 TD (NP) | - | 31.57 ± 5.56 | - | - | - | - | - | 38.76 ± 1.3 | 3362 ± 559 |

| 17 PTB | - | 28.83 ± 3.58 | - | - | - | - | - | 32.65 ± 3.02 | 1970 ± 524 | ||

| 6 PE/HELLP | - | 32.51 ± 6.79 | - | - | - | - | - | 30.33 ± 2.251 | 1181 ± 331 |

| Study Population | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | Proteinuria (>5 g/24 h) | Premonitory Symptoms | Tendon Reflexes | Abdominal Pain | Low PTL | Hepatic Enzymes | Pulmonary Edema | Fetal Distress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmidt, A. P. (2004) [44] | 18 PE | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 HT | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 10 ECL | 160.0 ± 18.0 | 102.2 ± 18.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 16 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Vettorazzi, J. (2012) [45] | 15 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12 MPE | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 34 SPE (8/34 HELLP) (5/34 ECL) | 165.5 ± 23.0 | 105.9 ± 16.7 | 16 (47.1) | 18 (53%) | - | 1 (2.9%) | 13 (37.1%) | 7 (20.6%) | 1 (2.9%) | 6 (17.6%) | |

| Wikström, A. K. (2012) [46] | 37 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 16 PE | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Bergman L. (2014) [47] | 53 PE | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 58 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Artunc-Ulkumen B. (2015) [48] | 27 SPE (8/27 HELLP) | 171.1 ± 20.8 | 102.5 ± 14.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 |

| 36 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Bergman L. (2016) [49] | 54 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 48 PE | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Wu, J. (2021) [50] | 9 early PE | 160–190 | 100–120 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | PBI FGR NST |

| 13 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Andersson M. (2021) [51] | 15 SPE | - | - | - | 9 (60%) | 2 (13%) | 1 (7) | 3 (20%) | 5 (33%) | - | - |

| 15 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Friis, T. (2022) [52] | 28 PE (16/28 SPE) | - | - | - | 10 (36%) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 28 NP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 16 non-pregnant | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Busse, M. (2022) [38] | 17 TD (NP) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 17 PTB | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 6 PE/HELLP | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | 6 | - | - |

| Author (Year) | Sample Type | Method | Study Population | Sampling Time | S100B Levels | p | Sensitivity–Specificity–Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmidt, A. P. (2004) [44] | Serum | Sangtec 100, ELISA, Diasorin, MN (µg/L) | 18 PE | 34.7 ± 4.1 weeks | 0.185 (0.14) | <0.05 Between ECL and all other groups | - |

| 11 HT | 36.8 ± 1.9 weeks | 0.186 (0.12) | |||||

| 10 ECL | 33.5 ± 3.9 weeks | 0.424 (0.194) | |||||

| 16 NP | 34.6 ± 6.4 weeks | 0.147 (0.07) | |||||

| Vettorazzi, J. (2012) [45] | Serum |

Luminescence assay (LIAmat Sangtec 100, Sweden) (µg/L) | 15 NP | - | 0.04 ± 0.05 | - | - |

| 12 MPE | - | 0.07 ± 0.05 | - | ||||

| 34 SPE (8/34 HELLP) (5/34 ECL) | - | 0.2 0 ± 0.19 |

0.002 to NP 0.003 to MPE | ||||

| Wikström, A. K. (2012) [46] | Plasma | Sangtec 100 ELISA, Diasorin, MN (µg/L) | 37 NP | 10, 25, 28, 33, 37 weeks | 0.047–0.052 | 0.71 within group <0.05 at 33 and 37 week vs. PE group | - |

| 16 PE | 0.052–0.075 | <0.05 within group | |||||

| Bergman L. (2014) [47] | Plasma | Sangtec 100 ELISA, Diasorin, MN (µg/L) | 53 PE | 35.2 ± 4.4 weeks | 0.12 (0.02–0.77) | <0.001 | Cutoff: 0.14 µg/L Sensitivity: 44% Specificity: 86% AUC: 0.71 |

| 58 NP | 34.5 ± 4.8 weeks | 0.07 (0.02–0.31) | |||||

| Artunc-Ulkumen B. (2015) [48] | Serum | Bio Vendor ELISA (Cobas e 411, Roche) (µg/L) | 27 SPE (8/27 HELLP) | - | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.025 | Cutoff: 0.0975 µg/L Sensitivity: 81.4% Specificity: 58.3% AUC: 0.712 PPV: 59.45% NPV: 80.7 |

| 36 NP | - | 0.09 ± 0.05 | |||||

| Bergman L. (2016) [49] | Plasma | Sangtec 100 ELISA, Diasorin, MN (µg/L) | 53 NP | 398 ± 36 days post delivery | 0.06 (0.04–0.07) | <0.05 | - |

| 58 PE | 406 ± 40 days post delivery | 0.07 (0.06–0.09) | |||||

| Wu, J. (2021) [50] | Plasma | ELISA ng/mL SPRi ng/mL | 9 early PE | 32–34 weeks | 198.91 ± 51.02 209.01 ± 27.54 | 0.007 for ELISA <0.001 for SPRi | >178 ng/mL (ELISA) >181 ng/mL (SPRi) Sens: 66/100% (ELISA/SPRi) Spec:44/84% (ELISA/SPRi) |

| ELISA ng/mL SPRi ng/mL | 13 NP | 111.63 ± 42.64 115.18 ± 51.02 | |||||

| Andersson M. (2021) [51] | Serum | Cobas Elecsys platform (µg/L) | 15 PE | 243 days | 0.08 (0.06–0.1) | <0.01 | - |

| 15 NP | 273.5 days | 0.05 (0.04–0.06) | |||||

| Friis, T. (2022) [52] | Plasma | Sangtec 100 ELISA, Diasorin, MN (µg/L) | 28 PE (SPE16/28) | 35 (29–37) weeks | 0.08 IQR 0.05–0.10 | <0.01 | - |

| 28 NP | 35 (27–38) weeks |

0.05 IQR 0.03–0.08 | |||||

| 16 non-pregnant | - | - | - | - | |||

| Busse, M. (2022) [38] | Plasma | ELISA R&D systems USA (pg/mL) | 17 TD (NP) | 38.76 ± 1.3 weeks | - | TD vs. PTB: <0.001 TD vs. PE/HELLP: 0.009 | - |

| 17 PTB | 32.65 ± 3.02 weeks | - | |||||

| 6 PE/HELLP | 30.33 ± 2.251 weeks | - | - |

| Study | Conclusions |

|---|---|

| Schmidt, A. P. (2004) [44] | Increased level of S100B in maternal serum is likely to be associated with eclampsia. |

| Vettorazzi, J., (2012) [45] | Elevated serum S100B levels in pregnant women with SPE suggest some kind of neural damage and subsequent astrocytic release of S100B. As no difference was detected between women with SPE and those with eclampsia, S100B changes were not dependent on the progression from severe preeclampsia to eclampsia. |

| Wikström, A. K. (2012) [46] | Levels of S100B in maternal plasma are increased during pregnancy in women who develop preeclampsia compared to healthy pregnancies, and the levels of S100B increase several weeks before clinical symptoms of the disease appear. |

| Bergman L. (2014) [47] | Plasma levels of S100B are elevated among women with preeclampsia compared with control subjects; furthermore, they increase irrespective of blood pressure level, showing association with visual disturbances, which might reflect possible CNS effects. |

| Artunc-Ulkumen B. (2015) [48] | Serum S100B levels may be a potential marker in severe preeclampsia for the severity of hypoperfusion in the brain and placenta, as well as the subsequent risk of organ failure. |

| Bergman L. (2016) [49] | The levels of NSE and S100B are significantly elevated in pregnant women with preeclampsia compared to those with normotensive pregnancies and persist up to one year postpartum, suggesting potential long-term neurological implications in individuals with a history of preeclampsia. |

| Wu, J. (2021) [50] | Increased levels of S100B in maternal plasma and amniotic fluid in early-onset SPE, but not in the cord blood (CB) plasma. There is a positive correlation in S100B concentration between maternal plasma and amniotic fluid. SPRi-S100B is more sensitive to ELISA-S100B for the diagnosis of early-onset SPE. |

| Andersson M. (2021) [51] | Women with preeclampsia demonstrated increased serum and plasma concentrations of S100B and NfL, respectively. Concentrations of NfL, but not S100B, were increased in CSF compared to women with normal pregnancies. Neurofilament light chain emerged as a promising circulating cerebral biomarker in preeclampsia. |

| Friis, T. (2022) [52] | Increased circulating concentrations of S100B, NfL, tau, and NSE were present in the maternal plasma of women developing SPE. Concentrations of NfL were also higher in women with PE compared with non-pregnant women. NfL could be a promising biomarker for BBB alterations in preeclampsia. |

| Busse, M. (2022) [38] | Εnhanced S100B concentration in maternal and CB plasma in women with preterm birth (PTB) and women with preterm delivery following PE/HELLP diagnosis, compared to women with term delivery (TD). S100B was positively correlated with interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels. S100B expression was enhanced in inflammatory events associated with PTB. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karampas, G.; Tzelepis, A.; Koulouraki, S.; Lykou, D.; Metallinou, D.; Erlandsson, L.; Panoulis, K.; Vlahos, N.; Hansson, S.R.; Eleftheriades, M. The Utility of Maternal Blood S100B in Women with Suspected or Established Preeclampsia—A Systematic Review. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15060840

Karampas G, Tzelepis A, Koulouraki S, Lykou D, Metallinou D, Erlandsson L, Panoulis K, Vlahos N, Hansson SR, Eleftheriades M. The Utility of Maternal Blood S100B in Women with Suspected or Established Preeclampsia—A Systematic Review. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(6):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15060840

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarampas, Grigorios, Athanasios Tzelepis, Sevasti Koulouraki, Despoina Lykou, Dimitra Metallinou, Lena Erlandsson, Konstantinos Panoulis, Nikolaos Vlahos, Stefan Rocco Hansson, and Makarios Eleftheriades. 2025. "The Utility of Maternal Blood S100B in Women with Suspected or Established Preeclampsia—A Systematic Review" Biomolecules 15, no. 6: 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15060840

APA StyleKarampas, G., Tzelepis, A., Koulouraki, S., Lykou, D., Metallinou, D., Erlandsson, L., Panoulis, K., Vlahos, N., Hansson, S. R., & Eleftheriades, M. (2025). The Utility of Maternal Blood S100B in Women with Suspected or Established Preeclampsia—A Systematic Review. Biomolecules, 15(6), 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15060840