A Review on Pathophysiology, and Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Chondronecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Commercial Broilers

Abstract

1. Introduction

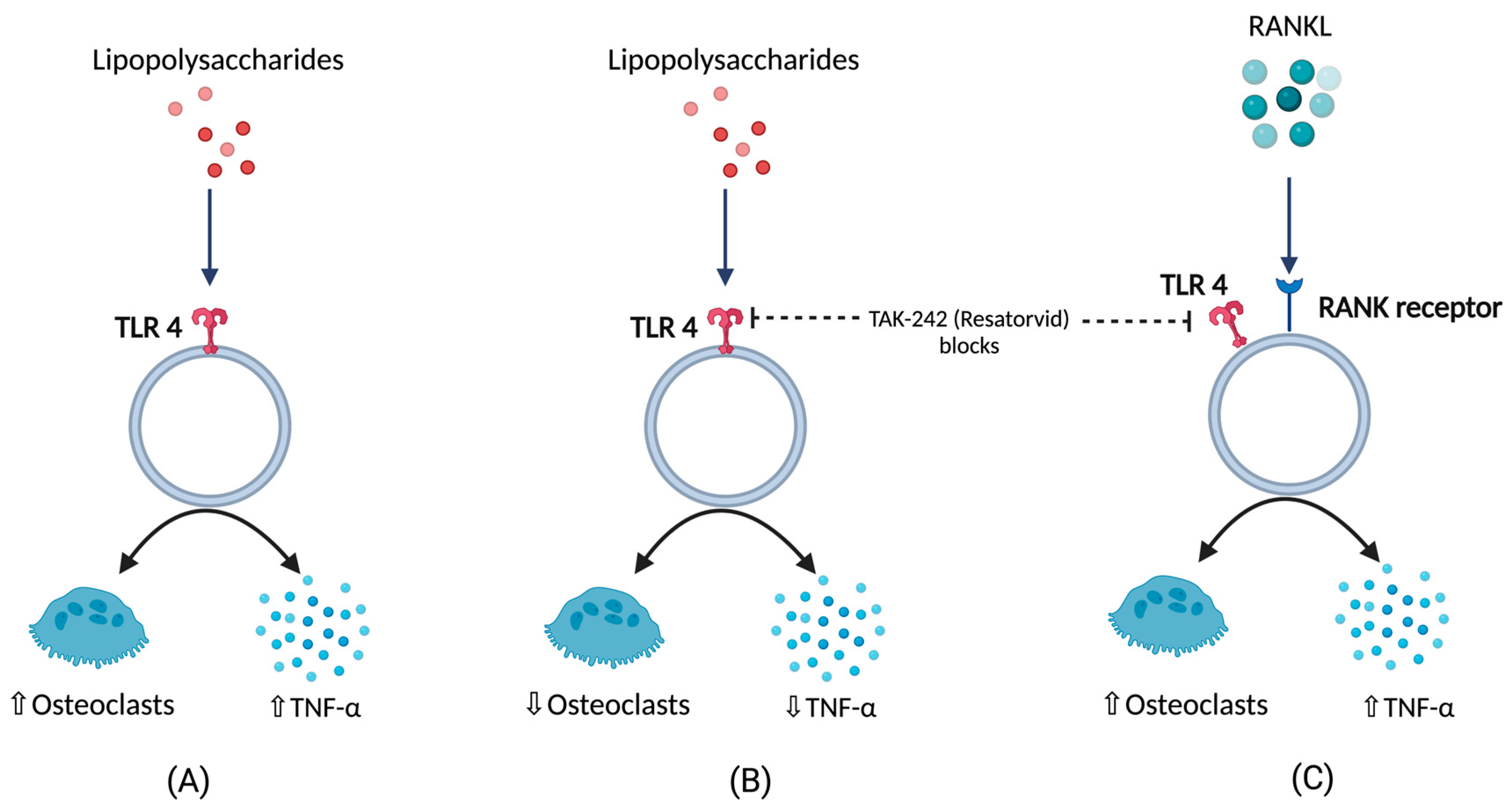

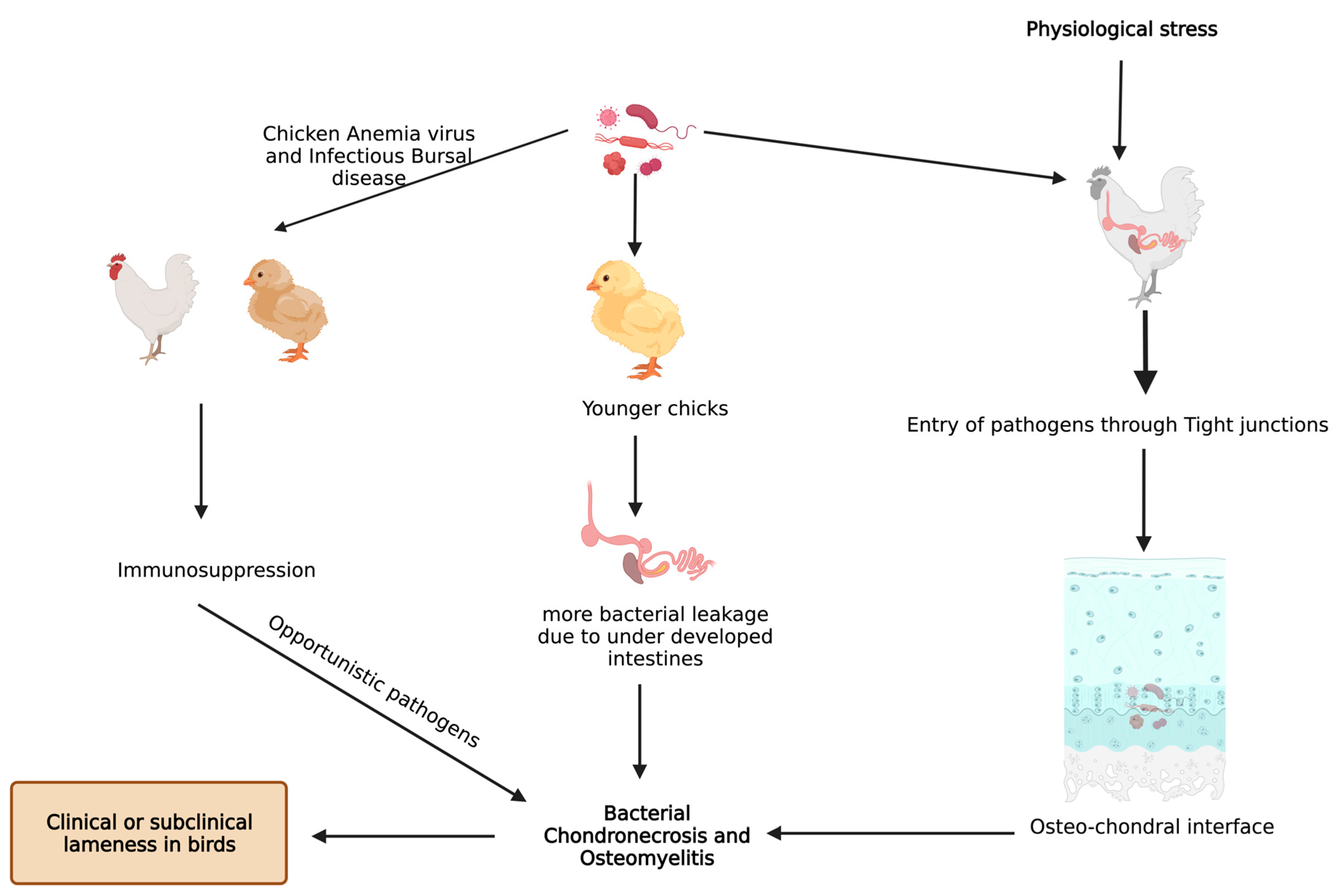

2. Inflammation and BCO

3. Pathogens and BCO

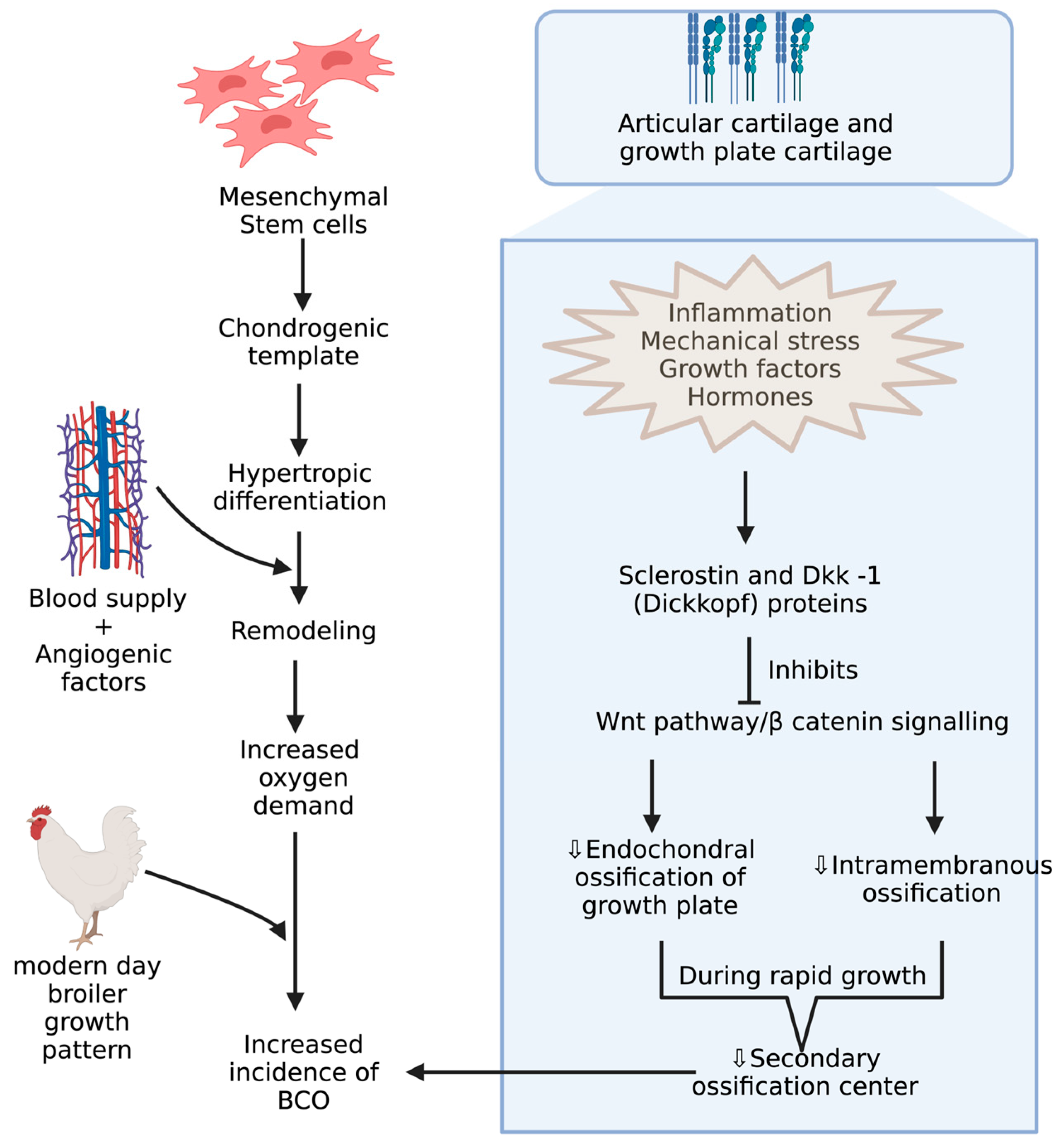

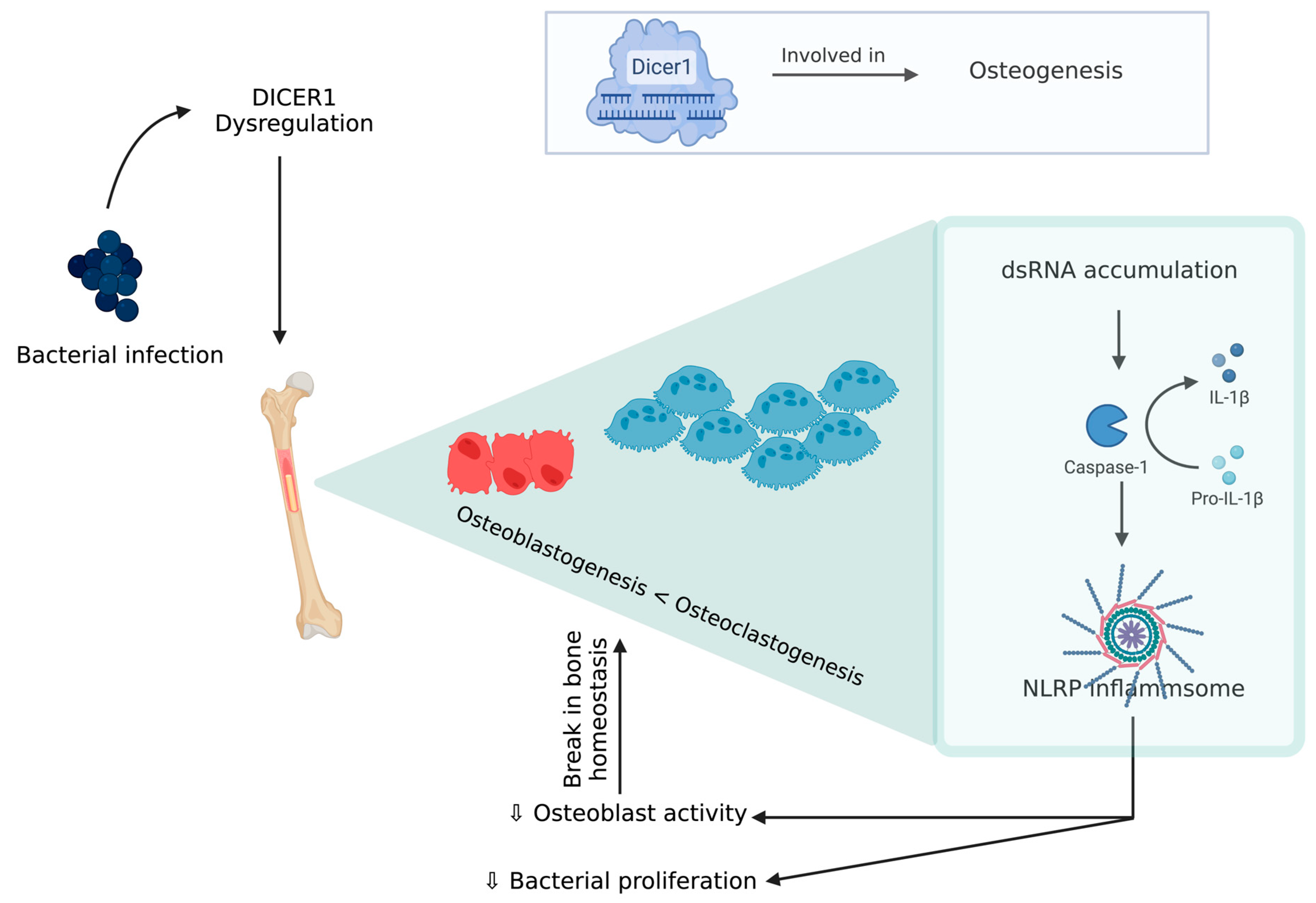

4. Underlying Anatomy and Physiology behind BCO and Its Potential Biomarkers

5. Influences of Gut Microbiota in BCO

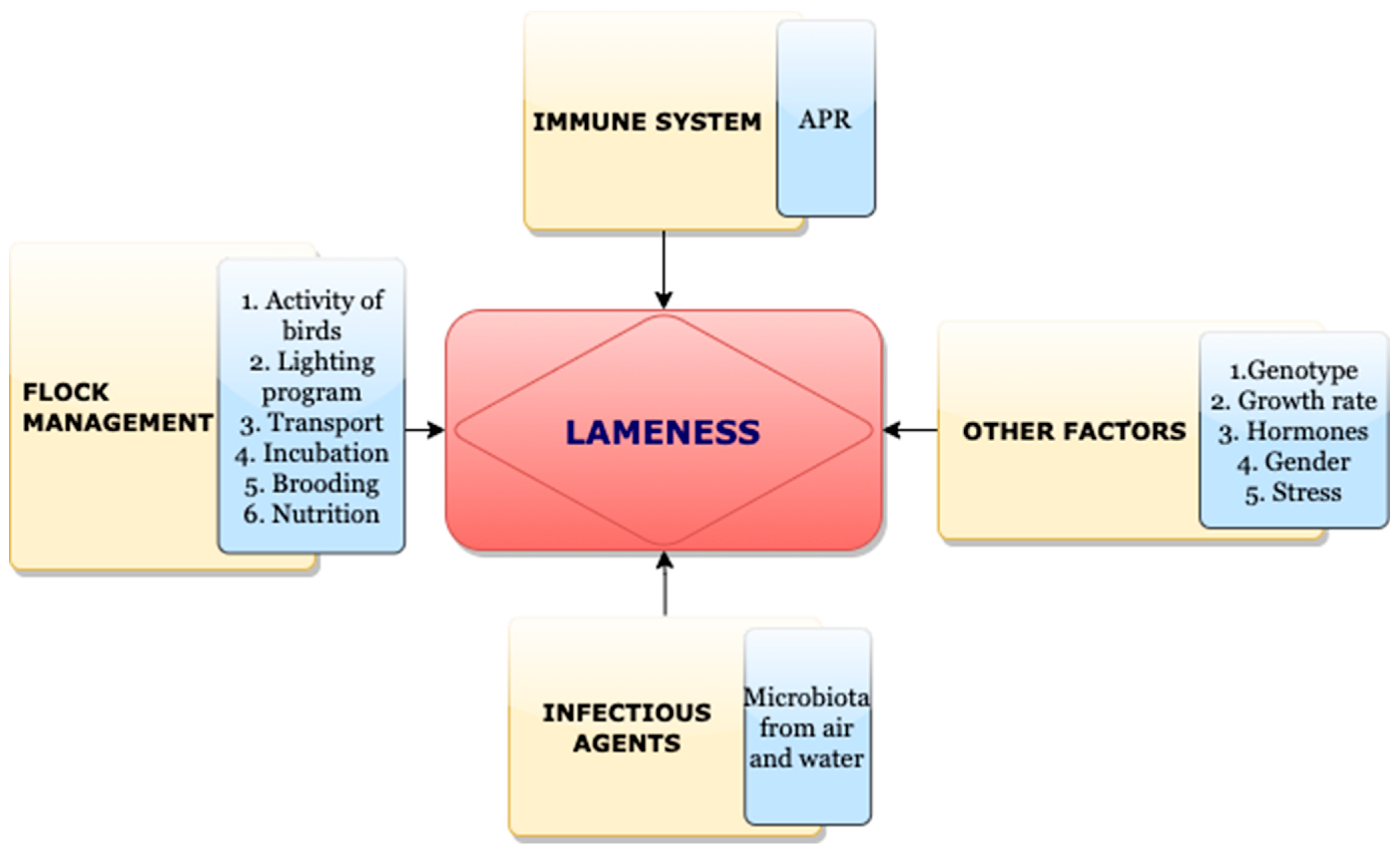

6. Miscellaneous Predisposing Factors for BCO

7. Bacterial Diversities through Culture Independent Methods

8. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Cultures—A Potential Tool to Understand BCO

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Amelio, P.; Sassi, F. Osteoimmunology: From mice to humans. Bonekey Rep. 2016, 5, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havenstein, G.B.; Ferket, P.R.; Qureshi, M.A. Growth, livability, and feed conversion of 1957 versus 2001 broilers when fed representative 1957 and 2001 broiler diets. Poult. Sci. 2003, 82, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packialakshmi, B.; Liyanage, R.; Lay, J.O., Jr.; Okimoto, R.; Rath, N.C. Prednisolone-induced predisposition to femoral head separation and the accompanying plasma protein changes in chickens. Biomark. Insights 2015, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.E. Skeletal deformities and their causes: Introduction. Poult. Sci. 2000, 79, 982–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, R. Production and growth related disorders and other metabolic diseases of poultry—A review. Vet. J. 2005, 169, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferver, A.; Dridi, S. Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis (BCO) in modern broilers: Impacts, mechanisms, and perspectives. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2020, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, R.H.; Kirkden, R.D.; Broom, D.M. A review of the aetiology and pathology of leg weakness in broilers in relation to welfare. Avian Poult. Biol. Rev. 2002, 13, 45–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, T.G.; Kestin, S.C.; Haslam, S.M.; Brown, S.N.; Green, L.E.; Butterworth, A.; Pope, S.J.; Pfeiffer, D.; Nicol, C.J. Leg Disorders in Broiler Chickens: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Prevention. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Núñez, I.; Moore, A.F.; Gino Lorenzoni, A. Incidence of bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis (Femoral head necrosis) induced by a model of skeletal stress and its correlation with subclinical necrotic enteritis. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, P.T.; Smyth, J.A. Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis (‘femoral head necrosis’) of broiler chickens: A review. Avian Pathol. 2000, 29, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, M. Impacts of bone problems on the poultry meat industry. In Bone Biology and Skeletal Disorders in Poultry, Poultry Science Symposium; Whitehead, C.C., Ed.; Carfax Publishing Co.: Abingdon, UK, 1992; pp. 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- McNamee, P.T.; McCullagh, J.J.; Thorp, B.H.; Ball, H.J.; Graham, D.; McCullough, S.J.; McConaghy, D.; Smyth, J.A. Study of leg weakness in two commercial broiler flocks. Vet. Rec. 1998, 143, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, I. Clinical and morphological investigations on the prevalence of lameness associated with femoral head necrosis in broilers. Br. Poult. Sci. 2009, 50, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Mandal, R.K.; Wideman, R.F., Jr.; Khatiwara, A.; Pevzner, I.; Min Kwon, Y. Molecular survey of bacterial communities associated with bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis (BCO) in broilers. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocsik, É.; Silvera, A.M.; Hansson, H.; Saatkamp, H.W.; Blokhuis, H.J. Exploring the economic potential of reducing broiler lameness. Br. Poult. Sci. 2017, 58, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nääs, I.A.; Paz, I.C.L.A.; Baracho, M.S.; Menezes, A.G.; Bueno, L.G.F.; Almeida, I.C.L.; Moura, D.J. Impact of lameness on broiler well-being. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2009, 18, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, B.V.; Guinane, C.M.; Ben Zakour, N.L.; Weinert, L.A.; Conway-Morris, A.; Cartwright, R.A.; Simpson, A.J.; Rambaut, A.; Nübel, U.; Fitzgerald, J.R. Recent human-to-poultry host jump, adaptation, and pandemic spread of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19545–19550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R.F. Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis and lameness in broilers: A review. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R.; Prisby, R. Bone Circulatory Disturbances in the Development of Spontaneous Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis: A Translational Model for the Pathogenesis of Femoral Head Necrosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 3, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasing, K.C. Avian macrophages: Regulators of local and systemic immune responses. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, H.; Gauldie, J. The acute phase response. Immunol. Today 1994, 15, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koj, A. The Role of Interleukin-6 as the Hepatocyte Stimulating Factor in the Network of Inflammatory Cytokines. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1989, 557, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, I.; Rzewnicki, D.L. The acute phase response: General aspects. Baillieres Clin. Rheumatol. 1994, 8, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, N.C.; Huff, G.R.; Huff, W.E.; Balog, J.M. Factors regulating bone maturity and strength in poultry. Poult. Sci. 2000, 79, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, S.; Orcel, P. Bone loss: Factors that regulate osteoclast differentiation—An update. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2000, 2, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mireles, A.J.; Kim, S.M.; Klasing, K.C. An Acute Inflammatory Response Alters Bone Homeostasis, Body Composition, and the Humoral Immune Response of Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasing, K.C.; Johnstone, B.J. Monokines in growth and development. Poult. Sci. 1991, 70, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggers, E.C.; Johnson, W.; Tucci, M.; Benghuzzi, H. Biochemical and morphological changes associated with macrophages and osteoclasts when challenged with infection-biomed 2011. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 2011, 47, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- AlQranei, M.S.; Senbanjo, L.T.; Aljohani, H.; Hamza, T.; Chellaiah, M.A. Lipopolysaccharide- TLR-4 Axis regulates Osteoclastogenesis independent of RANKL/RANK signaling. BMC Immunol. 2021, 22, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriott, I. Apoptosis-associated uncoupling of bone formation and resorption in osteomyelitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013, 3, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesurendra, D.S.; Chamings, A.N.; Bushell, R.N.; Rourke, D.O.; Stevenson, M.; Marenda, M.S.; Noormohammadi, A.H.; Stent, A. Pathological and microbiological investigations into cases of bacterial chondronecrosis and osteomyelitis in broiler poultry. Avian Pathol. 2017, 46, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, R.L. Role of infectious agents in leg abnormalities in growing birds. In Bone Biology and Skeletal Disorders in Poultry, Poultry Science Symposium; Whitehead, C.C., Ed.; Carfax: Oxford, UK, 1992; pp. 231–263. [Google Scholar]

- Wideman, R.F., Jr.; Hamal, K.R.; Stark, J.M.; Blankenship, J.; Lester, H.; Mitchell, K.N.; Lorenzoni, G.; Pevzner, I. A wire-flooring model for inducing lameness in broilers: Evaluation of probiotics as a prophylactic treatment. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, P.T.; McCullagh, J.J.; Rodgers, J.D.; Thorp, B.H.; Ball, H.J.; Connor, T.J.; McConaghy, D.; Smyth, J.A. Development of an experimental model of bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis in broilers following exposure to Staphylococcus aureus by aerosol, and inoculation with chicken anaemia and infectious bursal disease viruses. Avian Pathol. 1999, 28, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.K.; Jiang, T.; Wideman, R.F.; Lohrmann, T.; Kwon, Y.M. Microbiota Analysis of Chickens Raised Under Stressed Conditions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrubaye, A.A.K.; Ekesi, N.S.; Hasan, A.; Elkins, E.; Ojha, S.; Zaki, S.; Dridi, S.; Wideman, R.F.; Rebollo, M.A.; Rhoads, D.D. Chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis in broilers: Further defining lameness-inducing models with wire or litter flooring to evaluate protection with organic trace minerals. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5422–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, R.C.; Hunt, J.R.; Gardiner, E.E. Influence of light intensity on behavior and performance of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 1988, 67, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvino, G.M.; Archer, G.S.; Mench, J.A. Behavioural time budgets of broiler chickens reared in varying light intensities. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 118, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, J.-L.; Clark, K.; Groves, P.J.; Cronin, G.M. Light intensity of 5 or 20 lux on broiler behavior, welfare and productivity. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deep, A.; Schwean-Lardner, K.; Crowe, T.G.; Fancher, B.I.; Classen, H.L. Effect of light intensity on broiler behaviour and diurnal rhythms. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 136, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, S.L.; Wideman, R.F.; Scanes, C.G.; Mauromoustakos, A.; Christensen, K.D.; Vizzier-Thaxton, Y. The utility of infrared thermography for evaluating lameness attributable to bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 1575–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R.F., Jr.; Blankenship, J.; Pevzner, I.Y.; Turner, B.J. Efficacy of 25-OH vitamin D3 prophylactic administration for reducing lameness in broilers grown on wire flooring. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1821–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, S.C.; Knowles, T.G.; Tinch, A.E.; Gregory, N.G. Prevalence of leg weakness in broiler chickens and its relationship with genotype. Vet. Rec. 1992, 131, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, S.C.; Su, G.; Sorensen, P. Different commercial broiler crosses have different susceptibilities to leg weakness. Poult. Sci. 1999, 78, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, H.; Anthony, N.B.; Corr, S.A.; Hutchinson, J.R. The effects of selective breeding on the architectural properties of the pelvic limb in broiler chickens: A comparative study across modern and ancestral populations. J. Anat. 2010, 217, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxton, H.; Daley, M.A.; Corr, S.A.; Hutchinson, J.R. The gait dynamics of the modern broiler chicken: A cautionary tale of selective breeding. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 3237–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applegate, T.J.; Lilburn, M.S. Growth of the femur and tibia of a commercial broiler line. Poult. Sci. 2002, 81, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tickle, P.G.; Paxton, H.; Rankin, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.R.; Codd, J.R. Anatomical and biomechanical traits of broiler chickens across ontogeny. Part I. Anatomy of the musculoskeletal respiratory apparatus and changes in organ size. PeerJ 2014, 2, e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, S.A.; Gentle, M.J.; McCorquodale, C.C.; Bennett, D. The effect of morphology on walking ability in the modern broiler: A gait analysis study. Anim. Welf. 2003, 12, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Sophia Fox, A.J.; Bedi, A.; Rodeo, S.A. The basic science of articular cartilage: Structure, composition, and function. Sports Health 2009, 1, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspden, R.M.; Hukins, D.W.L. Collagen organization in articular cartilage, determined by X-ray diffraction, and its relationship to tissue function. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B. Biol. Sci. 1981, 212, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie, E.; Ahmed, Y.A.; Tatarczuch, L.; Chen, K.-S.; Mirams, M. Endochondral ossification: How cartilage is converted into bone in the developing skeleton. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, A.P.; Dickson, I.R.; Freemont, A.J.; Grant, M.E. Comparative studies of type X collagen expression in normal and rachitic chicken epiphyseal cartilage. J. Cell Biol. 1989, 109, 1849–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houschyar, K.S.; Tapking, C.; Borrelli, M.R.; Popp, D.; Duscher, D.; Maan, Z.N.; Chelliah, M.P.; Li, J.; Harati, K.; Wallner, C. Wnt pathway in bone repair and regeneration—What do we know so far. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 6, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, K.L.; Chen, C.S.; Assoian, R.K. The mechanical regulation of integrin–cadherin crosstalk organizes cells, signaling and forces. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, H.M. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature 2003, 423, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Grayson, W.L.; Fröhlich, M.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Hypoxia and stem cell-based engineering of mesenchymal tissues. Biotechnol. Prog. 2009, 25, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehy, E.J.; Kelly, D.J.; O’Brien, F.J. Biomaterial-based endochondral bone regeneration: A shift from traditional tissue engineering paradigms to developmentally inspired strategies. Mater. Today Bio 2019, 3, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, D.A. A re-investigation of the centres of ossification in the avian skeleton at and after hatching. J. Anat. 1980, 130, 725–743. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7429964 (accessed on 28 April 2023). [PubMed]

- Breugelmans, S.; Muylle, S.; Cornillie, P.; Saunders, J.; Simoens, P. Age determination of poultry: A challenge for customs. Vlaams Diergeneeskd. Tijdschr. 2007, 76, 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rubaye, A.A.K.; Couger, M.B.; Ojha, S.; Pummill, J.F.; Koon, J.A., II; Wideman, R.F., Jr.; Rhoads, D.D. Genome analysis of Staphylococcus agnetis, an agent of lameness in broiler chickens. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, B.; Savoldi, I.R.; Ibelli, A.M.G.; Paludo, E.; de Oliveira Peixoto, J.; Jaenisch, F.R.F.; de Córdova Cucco, D.; Ledur, M.C. New genes involved in the Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis in commercial broilers. Livest. Sci. 2018, 208, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, S.L.; Wideman, R.F.; Scanes, C.G.; Mauromoustakos, A.; Christensen, K.D.; Vizzier-Thaxton, Y. Broiler stress responses to light intensity, flooring type, and leg weakness as assessed by heterophil-to-lymphocyte ratios, serum corticosterone, infrared thermography, and latency to lie. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 3301–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.K.; Jiang, T.; Al-Rubaye, A.A.; Rhoads, D.D.; Wideman, R.F.; Zhao, J.; Pevzner, I.; Kwon, Y.M. An investigation into blood microbiota and its potential association with Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO) in Broilers. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalker, M.J.; Brash, M.L.; Weisz, A.; Ouckama, R.M.; Slavic, D. Arthritis and osteomyelitis associated with Enterococcus cecorum infection in broiler and broiler breeder chickens in Ontario, Canada. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2010, 22, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durairaj, V.; Okimoto, R.; Rasaputra, K.; Clark, F.D.; Rath, N.C. Histopathology and serum clinical chemistry evaluation of broilers with femoral head separation disorder. Avian Dis. 2009, 53, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, W.H. Experimental staphylococcal infections in chickens. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1954, 47, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Jawhari, J.J.; Ganguly, P.; Jones, E.; Giannoudis, P.V. Bone Marrow Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells as Autologous Therapy for Osteonecrosis: Effects of Age and Underlying Causes. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerachian, M.A.; Séguin, C.; Harvey, E.J. Glucocorticoids in osteonecrosis of the femoral head: A new understanding of the mechanisms of action. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 114, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paludo, E.; Ibelli, A.M.G.; Peixoto, J.D.O.; Tavernari, F.D.C.; Zanella, R.; Pandolfi, J.R.C.; Coutnho, L.; Lima-Rosa, C.A.V.; Ledur, M.C. RUNX2 plays an essential role in the manifestation of femoral head necrosis in broilers. In Proceedings of the 10th World Congress of Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil, 22 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.F.; Zhou, Z.L.; Shi, C.Y.; Hou, J.F. Downregulation of basic fibroblast growth factor is associated with femoral head necrosis in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durairaj, V.; Clark, F.D.; Coon, C.C.; Huff, W.E.; Okimoto, R.; Huff, G.R.; Rath, N.C. Effects of high fat diets or prednisolone treatment on femoral head separation in chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2012, 53, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandridis, E.; Apergis, G.; Korres, D.S.; Nikolopoulos, K.; Zoubos, A.B.; Papassideri, I.; Trougakos, I.P. Increased expression levels of apolipoprotein J/clusterin during primary osteoarthritis. In Vivo 2011, 25, 745–749. [Google Scholar]

- Di Angelantonio, E.; Sarwar, N.; Perry, P.; Kaptoge, S.; Ray, K.K.; Thompson, A.; Wood, A.M.; Lewington, S.; Sattar, N.; Packard, C.J.; et al. Major Lipids, Apolipoproteins, and Risk of Vascular Disease. JAMA 2009, 302, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, E.; Flees, J.; Dhamad, A.; Alrubaye, A.; Hennigan, S.; Pleimann, J.; Smeltzer, M.; Murray, S.; Kugel, J.; Goodrich, J.; et al. Double-Stranded RNA Is a Novel Molecular Target in Osteomyelitis Pathogenesis: A Translational Avian Model for Human Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 2077–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, A.; Kashima, R. Dysregulation of microRNA biogenesis machinery in cancer. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 51, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-F.; Murchison, E.P.; Tang, R.; Callis, T.E.; Tatsuguchi, M.; Deng, Z.; Rojas, M.; Hammond, S.M.; Schneider, M.D.; Selzman, C.H. Targeted deletion of Dicer in the heart leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2111–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Song, J.; Tang, Y.; Deng, F.; Zheng, L. Dicer-dependent pathway contribute to the osteogenesis mediated by regulation of Runx2. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 5354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Tu, Q.; Meng, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, L.; Song, J.; Hu, Y.; Sui, L.; Zhang, J.; Dard, M. Runx2/DICER/miRNA pathway in regulating osteogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendre, A.; Moritz, N.; Väänänen, V.; Määttä, J.A. Dicer1 ablation in osterix positive bone forming cells affects cortical bone homeostasis. Bone 2018, 106, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Baumgart, M.; Groth, M.; Wittmann, J.; Jäck, H.-M.; Platzer, M.; Tuckermann, J.P.; Baschant, U. Dicer ablation in osteoblasts by Runx2 driven cre-loxP recombination affects bone integrity, but not glucocorticoid-induced suppression of bone formation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paludo, E.; Ibelli, A.M.G.; Peixoto, J.O.; Tavernari, F.C.; Lima-Rosa, C.A.V.; Pandolfi, J.R.C.; Ledur, M.C.; Elgheznawy, A.; Shi, L.; Hu, J.; et al. The involvement of RUNX2 and SPARC genes in the bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis in broilers. Animal 2015, 117, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Kanneganti, T.-D. The cell biology of inflammasomes: Mechanisms of inflammasome activation and regulation. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 213, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, S.H.; Sahraei, M.; Young, A.B.; Worley, C.S.; Duncan, J.A.; Ting, J.P.; Marriott, I. Osteoblasts express NLRP3, a nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat region containing receptor implicated in bacterially induced cell death. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, P.; Burton, A.; Kanneganti, T.-D. NLRP3 inflammasome plays a redundant role with caspase 8 to promote IL-1β–mediated osteomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4452–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, J.; Ison, J.; Voor, M.J.; Tyagi, N. Exercise-linked skeletal irisin ameliorates diabetes-associated osteoporosis by inhibiting the oxidative damage–dependent miR-150-FNDC5/pyroptosis axis. Diabetes 2022, 71, 2777–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ling, J.; Jiang, Q. Inflammasomes in alveolar bone loss. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 691013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiku, V.; Tan, M.-W.; Dikic, I. Mitochondrial functions in infection and immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, N.; Lutz, A.K.; Haass, C.; Winklhofer, K.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: Molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological consequences. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 3038–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Armada, M.J.; Riveiro-Naveira, R.R.; Vaamonde-García, C.; Valcárcel-Ares, M.N. Mitochondrial dysfunction and the inflammatory response. Mitochondrion 2013, 13, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczenik, S.R.; Neustadt, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and molecular pathways of disease. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2007, 83, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genestier, A.-L.; Michallet, M.-C.; Prévost, G.; Bellot, G.; Chalabreysse, L.; Peyrol, S.; Thivolet, F.; Etienne, J.; Lina, G.; Vallette, F.M. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin directly targets mitochondria and induces Bax-independent apoptosis of human neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3117–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivitz, W.I.; Yorek, M.A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes: From molecular mechanisms to functional significance and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 537–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maassen, J.A.; ‘t Hart, L.M.; Van Essen, E.; Heine, R.J.; Nijpels, G.; Jahangir Tafrechi, R.S.; Raap, A.K.; Janssen, G.M.; Lemkes, H.H. Mitochondrial diabetes: Molecular mechanisms and clinical presentation. Diabetes 2004, 53, S103–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haden, D.W.; Suliman, H.B.; Carraway, M.S.; Welty-Wolf, K.E.; Ali, A.S.; Shitara, H.; Yonekawa, H.; Piantadosi, C.A. Mitochondrial biogenesis restores oxidative metabolism during Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Clapier, R.; Garnier, A.; Veksler, V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: The central role of PGC-1α. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 79, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, A.D.; Piantadosi, C.A. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and its intersection with inflammatory responses. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 22, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hock, M.B.; Kralli, A. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009, 71, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chomyn, A.; Chan, D.C. Disruption of fusion results in mitochondrial heterogeneity and dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 26185–26192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipolat, S.; de Brito, O.M.; Dal Zilio, B.; Scorrano, L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15927–15932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, K.; Licknack, T.; Watson, D.L.; Anthony, N.B.; Rhoads, D.D. Further investigation of mitochondrial biogenesis and gene expression of key regulators in ascites-susceptible and ascites-resistant broiler research lines. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0205480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferver, A.; Greene, E.; Wideman, R.; Dridi, S. Evidence of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis–Affected Broilers. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 640901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, C.Y.; Zhou, Z.L.; Hou, J.F. Bone characteristics, histopathology, and chondrocyte apoptosis in femoral head necrosis induced by glucocorticoid in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Waddington, D.; Murray, D.H.; Farquharson, C. Bone strength during growth: Influence of growth rate on cortical porosity and mineralization. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2004, 74, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packialakshmi, B.; Rath, A.N.C.; Huff, B.W.E.; Huff, G.R. Review Article-Poultry Femoral Head Separation and Necrosis: A Review. Avian Dis. 2015, 59, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, Y.; Liu, G.; Marshall, B.; Sharma, M.K.; Kim, W.K. Effect of Hydrogen Oxide-Induced Oxidative Stress on Bone Formation in the Early Embryonic Development Stage of Chicken. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; Feng, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, D.; Li, Z.; Sun, S. Network Pharmacology Deciphers the Action of Bioactive Polypeptide in Attenuating Inflammatory Osteolysis via the Suppression of Oxidative Stress and Restoration of Bone Remodeling Balance. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 4913534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oso, A.O.; Idowu, A.A.; Niameh, O.T. Growth response, nutrient and mineral retention, bone mineralisation and walking ability of broiler chickens fed with dietary inclusion of various unconventional mineral sources. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2011, 95, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Larose, J.; Kent, O.A.; Lim, M.; Changoor, A.; Zhang, L.; Storozhuk, Y.; Mao, X.; Grynpas, M.D.; Cong, F. RANKL coordinates multiple osteoclastogenic pathways by regulating expression of ubiquitin ligase RNF146. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, B.; Dong, Z.; Gao, L.; He, X.; Liao, L.; Hu, C.; Wang, Q.; Jin, Y. Lipopolysaccharide differentially affects the osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through Toll-like receptor 4 mediated nuclear factor κB pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Adhikari, R.; White, D.L.; Kim, W.K. Role of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) on Osteogenic Differentiation and Mineralization of Chicken Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 479596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Huang, E.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, N.; Chen, X.; Wang, N.; Wen, S.; Nan, G.; Deng, F. Crosstalk between Wnt/β-catenin and estrogen receptor signaling synergistically promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Chi, S.; Xue, J.; Yang, J.; Li, F.; Liu, X. Emerging role and therapeutic implication of Wnt signaling pathways in autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 9392132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Zylstra-Diegel, C.R.; Schumacher, C.A.; Baker, J.J.; Carpenter, A.C.; Rao, S.; Yao, W.; Guan, M.; Helms, J.A.; Lane, N.E. Wntless functions in mature osteoblasts to regulate bone mass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2197–E2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, D.A.; Bialek, P.; Ahn, J.D.; Starbuck, M.; Patel, M.S.; Clevers, H.; Taketo, M.M.; Long, F.; McMahon, A.P.; Lang, R.A. Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev. Cell 2005, 8, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekesi, N.S.; Dolka, B.; Alrubaye, A.A.K.; Rhoads, D.D. Analysis of genomes of bacterial isolates from lameness outbreaks in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, M.; Speers, D.; Emslie, K.; Nade, S. Acute haematogenous osteomyelitis and septic arthritis—A single disease. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1986, 68B, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Carrasco, J.M.; Casanova, N.A.; Fernández Miyakawa, M.E. Microbiota, Gut Health and Chicken Productivity: What Is the Connection? Microorganisms 2019, 7, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.T.; Sharma, V.; Elmén, L.; Peterson, S.N. Immune homeostasis, dysbiosis and therapeutic modulation of the gut microbiota. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2015, 179, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, K.; Engdahl, C.; Henning, P.; Lerner, U.H.; Tremaroli, V.; Lagerquist, M.K.; Bäckhed, F.; Ohlsson, C. The gut microbiota regulates bone mass in mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvaneh, K.; Ebrahimi, M.; Sabran, M.R.; Karimi, G.; Hwei, A.N.M.; Abdul-Majeed, S.; Ahmad, Z.; Ibrahim, Z.; Jamaluddin, R. Probiotics (Bifidobacterium longum) increase bone mass density and upregulate Sparc and Bmp-2 genes in rats with bone loss resulting from ovariectomy. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 897639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.M. Diet, gut microbiome, and bone health. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2015, 13, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierończyk, B.; Rawski, M.; Józefiak, D.; Świątkiewicz, S. Infectious and non-infectious factors associated with leg disorders in poultry—A review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2017, 17, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Kornegay, E.T.; Denbow, D.M. Supplemental microbial phytase improves zinc utilization in broilers. Poult. Sci. 1996, 75, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintar, J.; Bujan, M.; Homen, B.; Gazic, K.; Sikiric, M.; Cerny, T. Effects of supplemental phytase on the mineral content in tibia of broilers fed different cereal based diets. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 50, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štofaníková, J.; Šály, J.; Molnar, L.; Sesztáková, E.; Bilek, J. The influence of dietary zinc content on mechanical properties of chicken tibiotarsal bone. Acta Vet. Brno. 2011, 61, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jung, B.; Kim, W.K. Effects of lysophospholipid on growth performance, carcass yield, intestinal development, and bone quality in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 3902–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okiki, P.A.; Ojeizeh, T.I.; Ogbimi, A.O. Effects of feeding diet rich in mycotoxins on the health and growth performances of broiler chicken. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2010, 9, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.L.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Hong, Y.G.; Kim, W.K. The effect of total sulfur amino acid levels on growth performance, egg quality, and bone metabolism in laying hens subjected to high environmental temperature. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4982–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danzeisen, J.L.; Kim, H.B.; Isaacson, R.E.; Tu, Z.J.; Johnson, T.J. Modulations of the chicken cecal microbiome and metagenome in response to anticoccidial and growth promoter treatment. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speers, D.J.; Nade, S.M. Ultrastructural studies of adherence of Staphylococcus aureus in experimental acute hematogenous osteomyelitis. Infect. Immun. 1985, 49, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis-Ribas, T.; Forni, M.F.; Winnischofer, S.M.B.; Sogayar, M.C.; Trombetta-Lima, M. Extracellular matrix dynamics during mesenchymal stem cells differentiation. Dev. Biol. 2018, 437, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.J.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E.M. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talaei-Khozani, T.; Borhani-Haghighi, M.; Ayatollahi, M.; Vojdani, Z. An in vitro model for hepatocyte-like cell differentiation from Wharton’s jelly derived-mesenchymal stem cells by cell-base aggregates. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2015, 8, 188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ziadlou, R.; Shahhoseini, M.; Safari, F.; Sayahpour, F.-A.; Nemati, S.; Eslaminejad, M.B. Comparative analysis of neural differentiation potential in human mesenchymal stem cells derived from chorion and adult bone marrow. Cell Tissue Res. 2015, 362, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Seong, S.; Kim, K.; Kim, I.; Jeong, B.-C.; Kim, N. Downregulation of Runx2 by 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, R.; Chen, C.; Waters, E.; West, F.D.; Kim, W.K. Isolation and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from broiler chicken compact bones. Front. Physiol. 2019, 9, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, A.C.; Kouroupis, D.; Willman, M.A.; Perucca Orfei, C.; Agarwal, A.; Correa, D. Signature quality attributes of CD146+ mesenchymal stem/stromal cells correlate with high therapeutic and secretory potency. Stem Cells 2020, 38, 1034–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-K.; Meliton, V.; Tetradis, S.; Weinmaster, G.; Hahn, T.J.; Carlson, M.; Nelson, S.F.; Parhami, F. Osteogenic oxysterol, 20(S)-hydroxycholesterol, induces notch target gene expression in bone marrow stromal cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarkers | Function and Correlation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Serum Calcium | Bone density and mineralization along with bone breaking strength | [107,108] |

| IL-17, IL-6, TNF-α, NLRP-3 | Pyroptosis of osteoblasts, and Pro-inflammatory factors stimulates osteoclastogenesis or inhibits osteobalstogenesis | [106,109] |

| Peroxisome proliferator actvated receptor coactivator (PGC-1α, 1β) | Repress the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, Mitochondrial biogenesis | [106,110,111] |

| Mitofusins | Increased ROS production, | [106] |

| Matrix metalloproteases | Tissue remodeling, angiogenesis, Extracellular matrix degradation | [107,112] |

| Osteocalcin | Secreted by differentiating osteoblasts | [14,75,113] |

| RANKL and OPG | Crtitical cytokine produced by osteoblasts and OPG is an decoy receptor for RANKL | [83,114,115] |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Involved in Ca and P deposition during the bone mineralization and formation | [9,111,116] |

| Sclerostin, DICKKOPF protein | Inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway | [117,118,119,120] |

| Tartarate resistant Acid Phosphatase | Activity of osteoclasts | [19,109,111] |

| Thrombospondin, Interferon-γ, Tranforming growth factor-β, Vascular endothelial growth factor isoform-C, and Protocadherin-15 | Associated with the risk of avascular necrosis seen in BCO | [9,19,69,121] |

| Fibroblast growth factor-2, BMP, SMAD1 and RUNX-2 | Essential in osteoblast activity, bone mineralization, and osteoclast differentiation | [4,32,122] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choppa, V.S.R.; Kim, W.K. A Review on Pathophysiology, and Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Chondronecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Commercial Broilers. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13071032

Choppa VSR, Kim WK. A Review on Pathophysiology, and Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Chondronecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Commercial Broilers. Biomolecules. 2023; 13(7):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13071032

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoppa, Venkata Sesha Reddy, and Woo Kyun Kim. 2023. "A Review on Pathophysiology, and Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Chondronecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Commercial Broilers" Biomolecules 13, no. 7: 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13071032

APA StyleChoppa, V. S. R., & Kim, W. K. (2023). A Review on Pathophysiology, and Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Chondronecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Commercial Broilers. Biomolecules, 13(7), 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13071032