Fractatomic Physics: Atomic Stability and Rydberg States in Fractal Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Vector Calculus in Fractal Spaces

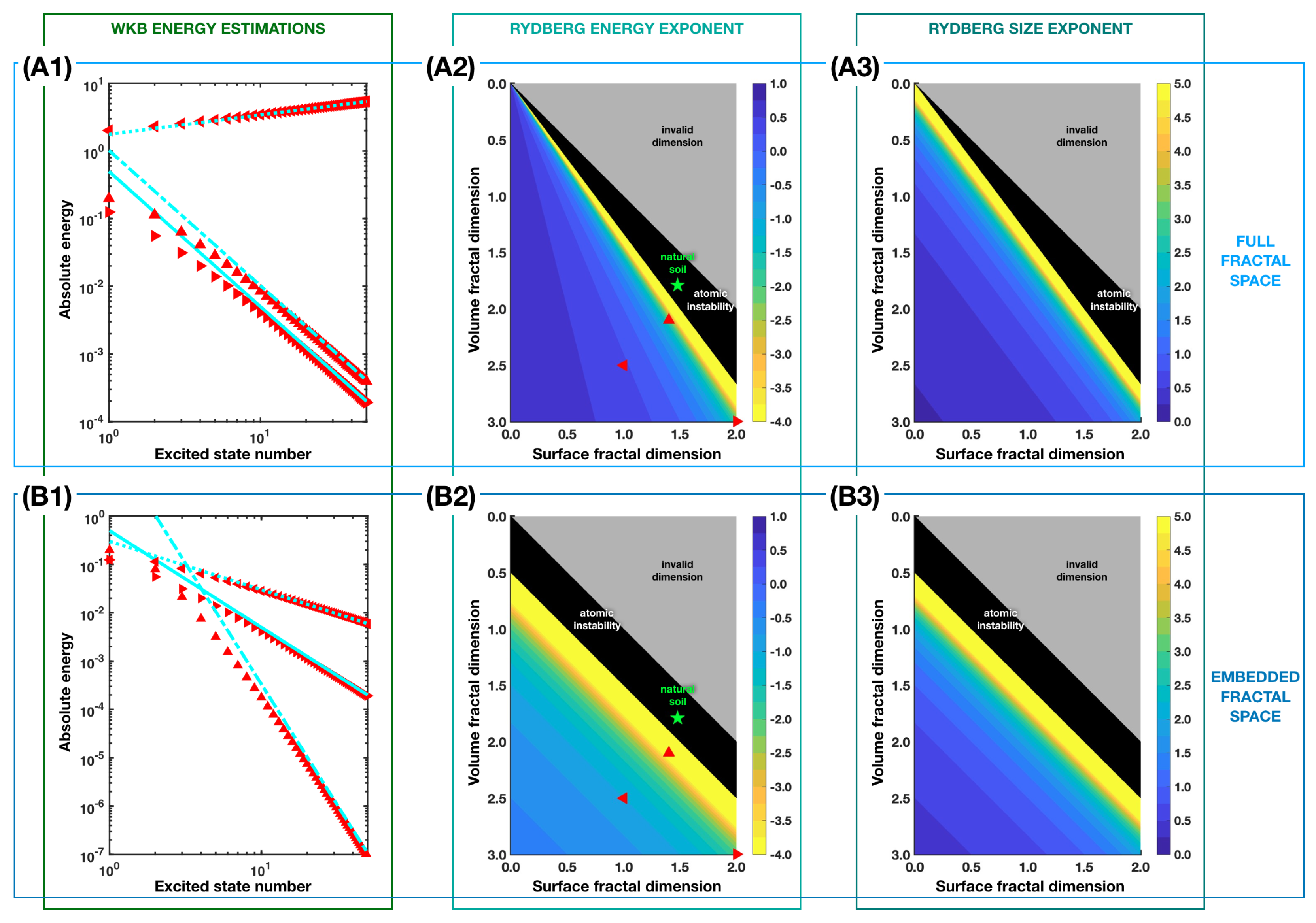

- The full fractal space, in which the electrical field and the electron propagate within the same fractal space. The coefficient in the expression Equation (4) for the interacting energy potential can be found to be the following:We show the derivation of this using fractal vector calculus in Appendix A.

- The embedded fractal space, where the electrical field spreads throughout the three-dimensional Euclidean space of our universe, while the electron is a quasi-particle residing on a fractal lattice embedded within those three dimensions. The coefficient in the expression Equation (4) for the interacting energy potential has the familiar form:This can also be found by setting in Equation (5).

3. Atomic Instability

3.1. Ehrenfest Finding in Euclidean Spaces

3.2. Scale-Free Schrödinger Equation in Euclidean Spaces

3.3. Scale-Free Schrödinger Equation in Fractal Spaces

- The full fractal space has , as found in Equation (5). Therefore, the fractality for scale-free atoms is as follows:This agrees with what we have found in Section 3.2 for Euclidean spaces.

- The embedded fractal space has , see Equation (6). Thus, scale-free atoms can be found at fractality satisfies the following:This indicates that the radial dimension should exhibits a strong fractal characteristics.

4. Rydberg States

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Coulomb Potential in Fractal Spaces

Appendix B. Generalized Langer Modification in Fractal Spaces

Appendix C. WKB Estimations for Rydberg Energies and Radius of Fractal Space Atoms

References

- Kleppner, D. A short history of atomic physics in the twentieth century. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999, 71, S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenfest, P. In what way does it become manifest in the fundamental laws of physics that space has three dimensions. Proc. Amst. Acad. 1917, 20, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Tangherlini, F.R. Schwarzschild field in n dimensions and the dimensionality of space problem. Il Nuovo Cimento (1955–1965) 1963, 27, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegmark, M. On the dimensionality of spacetime. Class. Quantum Gravity 1997, 14, L69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, K.; Fishbach, M.; Holz, D.E.; Spergel, D.N. Limits on the number of spacetime dimensions from GW170817. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2018, 2018, 048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shytov, A.; Katsnelson, M.; Levitov, L. Atomic collapse and quasi–Rydberg states in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 246802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casolo, S.; Løvvik, O.M.; Martinazzo, R.; Tantardini, G.F. Understanding adsorption of hydrogen atoms on graphene. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 054704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wong, D.; Shytov, A.V.; Brar, V.W.; Choi, S.; Wu, Q.; Tsai, H.Z.; Regan, W.; Zettl, A.; Kawakami, R.K.; et al. Observing atomic collapse resonances in artificial nuclei on graphene. Science 2013, 340, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, L. One-electron atom in curved space-time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 44, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Rydberg atoms in curved space-time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nottale, L. Scale relativity and fractal space-time: Applications to quantum physics, cosmology and chaotic systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 1996, 7, 877–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maker, D. Quantum physics and fractal space time. Chaos Solitons Fractals 1999, 10, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupriyanov, V. A hydrogen atom on curved noncommutative space. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2013, 46, 245303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allnatt, A.R.; Lidiard, A.B. Atomic Transport in Solids; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S. Quantum Transport: Atom to Transistor; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; WH Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Barnsley, M.F. Fractals Everywhere; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, T.V.; Morris, R.; Black, M.E.; Do, T.K.; Lin, K.C.; Nagy, K.; Sturm, J.C.; Bos, J.; Austin, R.H. Bacterial route finding and collective escape in mazes and fractals. Phys. Rev. X 2020, 10, 031017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Calvo, A.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Bay, R.K.; Luu, H.N.; Hancock, A.M.; Wingreen, N.S.; Datta, S.S. Morphological instability and roughening of growing 3D bacterial colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2208019119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arellano-Caicedo, C.; Ohlsson, P.; Bengtsson, M.; Beech, J.P.; Hammer, E.C. Habitat complexity affects microbial growth in fractal maze. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.V.; Cai, T.H.; Do, V.H. Vanishing in fractal space: Thermal melting and hydrodynamic collapse. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 033107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Flow of fractal fluid in pipes: Non-integer dimensional space approach. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2014, 67, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Anisotropic fractal media by vector calculus in non-integer dimensional space. J. Math. Phys. 2014, 55, 083510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Electromagnetic waves in non-integer dimensional spaces and fractals. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2015, 81, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Elasticity of fractal materials using the continuum model with non-integer dimensional space. Comptes Rendus Mec. 2015, 343, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Fractal electrodynamics via non-integer dimensional space approach. Phys. Lett. A 2015, 379, 2055–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Acoustic waves in fractal media: Non-integer dimensional spaces approach. Wave Motion 2016, 63, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, Q.A.; Fiaz, M.A. Electromagnetic behavior of a planar interface of non-integer dimensional spaces. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 2017, 31, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Fractional Dynamics: Applications of Fractional Calculus to Dynamics of Particles, Fields and Media; Springer Science & Business Media: Basel, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klafter, J.; Lim, S.; Metzler, R. Fractional Dynamics: Recent Advances; World Scientific: Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, V.E. General fractional dynamics. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Continuous medium model for fractal media. Phys. Lett. A 2005, 336, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Possible experimental test of continuous medium model for fractal media. Phys. Lett. A 2005, 341, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, P. Geometry of Sets and Measures in Euclidean Spaces: Fractals and Rectifiability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Number 44. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Martínez, M.; Sánchez-Granero, M. Fractal dimension for fractal structures. Topol. Its Appl. 2014, 163, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Review of some promising fractional physical models. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2013, 27, 1330005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domany, E.; Alexander, S.; Bensimon, D.; Kadanoff, L.P. Solutions to the Schrödinger equation on some fractal lattices. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 28, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Xu, M. Space–time fractional Schrödinger equation with time-independent potentials. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2008, 344, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodnianski, I. Fractal solutions of the Schrodinger equation. Contemp. Math. 2000, 255, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.P.; Molchanov, S.; Teplyaev, A. Spectral dimension and Bohr’s formula for Schrödinger operators on unbounded fractal spaces. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2015, 48, 395203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, M.I.; Akgül, A. A novel approach for solving linear and nonlinear time-fractional Schrödinger equations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 162, 112487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottale, L. Scale relativity and Schrödinger’s equation. Chaos Solitons Fractals 1998, 9, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, E.; Ganesh, R. Bound states without potentials: Localization at singularities. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 108, 022202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.L.; Berggren, K.F. Quantum bound states in narrow ballistic channels with intersections. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sols, F.; Macucci, M.; Ravaioli, U.; Hess, K. Theory for a quantum modulated transistor. J. Appl. Phys. 1989, 66, 3892–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, D.; Allmaras, R.; Nater, E.; Huggins, D. Fractal dimensions for volume and surface of interaggregate pores—scale effects. Geoderma 1997, 77, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Dai, J.; Zhou, X.; Kuttner, J.; Hilt, G.; Shao, X.; Gottfried, J.M.; Wu, K. Assembling molecular Sierpiński triangle fractals. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempkes, S.N.; Slot, M.R.; Freeney, S.E.; Zevenhuizen, S.J.; Vanmaekelbergh, D.; Swart, I.; Smith, C.M. Design and characterization of electrons in a fractal geometry. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Z.; Shi, C.Y.; An, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Mao, W.L.; Goddard, W.A., III; Greer, J.R. Fractal atomic-level percolation in metallic glasses. Science 2015, 349, 1306–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, T.F. Rydberg atoms. In Springer Handbook of Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Saffman, M.; Walker, T.G.; Mølmer, K. Quantum information with Rydberg atoms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, G. Eine verallgemeinerung der quantenbedingungen für die zwecke der wellenmechanik. Z. Für Phys. 1926, 38, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramers, H.A. Wellenmechanik und halbzahlige Quantisierung. Z. Phys. 1926, 39, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillouin, L. La mécanique ondulatoire de Schrödinger: Une méthode générale de resolution par approximations successives, Comptes Rendus de l’Academie des Sciences 183, 24 U26 (1926) HA Kramers. Wellenmechanik Und Halbzählige Quantisierung″ Zeit. F. Phys. 1926, 39, U840. [Google Scholar]

- Ao, V.D.; Tran, D.V.; Pham, K.T.; Nguyen, D.M.; Tran, H.D.; Do, T.K.; Do, V.H.; Phan, T.V. A Schrödinger Equation for Evolutionary Dynamics. Quantum Rep. 2023, 5, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, R.E. On the connection formulas and the solutions of the wave equation. Phys. Rev. 1937, 51, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.Y.; Dong, S.H. The improved quantization rule and the Langer modification. Phys. Lett. A 2008, 372, 1972–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppner, D.; Littman, M.G.; Zimmerman, M.L. Highly excited atoms. Sci. Am. 1981, 244, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, T.F. Rydberg atoms. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1988, 51, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.S.; Pritchard, J.D.; Shaffer, J.P. Rydberg atom quantum technologies. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2019, 53, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabtsev, I.I.; Tretyakov, D.B.; Beterov, I.I. Applicability of Rydberg atoms to quantum computers. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2005, 38, S421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, H.; Müller, M.; Lesanovsky, I.; Zoller, P.; Büchler, H.P. A Rydberg quantum simulator. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browaeys, A.; Lahaye, T. Many-body physics with individually controlled Rydberg atoms. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibel, E.R. Fractal geometry: A design principle for living organisms. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 1991, 261, L361–L369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, L. Fractal Geometry; Earthquake Publisher: Beijing, China, 1998; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Paumgartner, D.; Losa, G.; Weibel, E.R. Resolution effect on the stereological estimation of surface and volume and its interpretation in terms of fractal dimensions. J. Microsc. 1981, 121, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, W.; Mikula, R. Fractal dimensions of coal particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1987, 120, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Chatterji, B.N. Hyperspheres in digital geometry. Inf. Sci. 1990, 50, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, H.M. Riemann’s Zeta Function; Courier Corporation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 58. [Google Scholar]

- Ostoja-Starzewski, M. Continuum mechanics models of fractal porous media: Integral relations and extremum principles. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 2009, 4, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigami, J. Analysis on Fractals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; Number 143. [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg, U.; Zähle, M. Harmonic calculus on fractals-a measure geometric approach I. Potential Anal. 2002, 16, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmankhaneh, A.K.; Pellis, S.; Zingales, M. Fractal Schrödinger equation: Implications for fractal sets. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2024, 57, 185201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, E. The scattering of α and β particles by matter and the structure of the atom. Philos. Mag. 2012, 92, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, N. Atomic structure. Nature 1921, 107, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhtakia, A. Models and Modelers of Hydrogen: Thales, Thomson, Rutherford, Bohr, Sommerfeld, Goudsmit, Heisenberg, Schr Dinger, Dirac, Sallhofer; World Scientific: Singapore, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, T.V.; Doan, A. A Curious Use of Extra Dimension in Classical Mechanics: Geometrization of Potential. J. Geom. Graph. 2021, 25, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R.B. Consistent histories and the interpretation of quantum mechanics. J. Stat. Phys. 1984, 36, 219–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omnes, R. Consistent interpretations of quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1992, 64, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence and the transition from quantum to classical-revisited. Los Alamos Sci. 2002, 27, 86–109. [Google Scholar]

- Joos, E.; Zeh, H.D.; Kiefer, C.; Giulini, D.J.; Kupsch, J.; Stamatescu, I.O. Decoherence and the Appearance of a Classical World in Quantum Theory; Springer Science & Business Media: Basel, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen, C.J.; Niemax, K. Quantum Defects of the n2P1/2,3/2 Levels in 39K I and 85Rb I. Phys. Scr. 1983, 27, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.K. Semiclassical quantization and the Langer modification. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 6443–6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, M.; Bhaduri, R. Semiclassical Physics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kimble, H.J. The quantum internet. Nature 2008, 453, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Gill, A.T.; Isenhower, L.; Walker, T.G.; Saffman, M. Fidelity of a Rydberg-blockade quantum gate from simulated quantum process tomography. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 85, 042310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, T.; Goyal, K.; Jau, Y.Y.; Biedermann, G.W.; Landahl, A.J.; Deutsch, I.H. Adiabatic quantum computation with Rydberg-dressed atoms. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 052314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukin, M.D.; Fleischhauer, M.; Cote, R.; Duan, L.M.; Jaksch, D.; Cirac, J.I.; Zoller, P. Dipole Blockade and Quantum Information Processing in Mesoscopic Atomic Ensembles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 037901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.J.; Michailidis, A.A.; Abanin, D.A.; Serbyn, M.; Papić, Z. Quantum scarred eigenstates in a Rydberg atom chain: Entanglement, breakdown of thermalization, and stability to perturbations. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 155134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; Albash, T.; Blocher, P.D.; Takahashi, J.; Miyake, A.; Biedermann, G.W.; Deutsch, I.H. Macrostates vs. Microstates in the Classical Simulation of Critical Phenomena in Quench Dynamics of 1D Ising Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.08567. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Gaddie, A.; Do, H.V.; Biederman, G.W.; Lewis-Swan, R.J. Simulating a two component Bose-Hubbard model with imbalanced hopping in a Rydberg tweezer array. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.14846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanin, D.A.; Altman, E.; Bloch, I.; Serbyn, M. Colloquium: Many-body localization, thermalization, and entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2019, 91, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagoskin, A.M. Quantum Engineering: Theory and Design of Quantum Coherent Structures; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Varshalovich, D.A.; Moskalev, A.N.; Khersonskii, V.K. Quantum Theory of Angular Momentum; World Scientific: Singapore, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds, A.R. Angular Momentum in Quantum Mechanics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Fickler, R.; Lapkiewicz, R.; Plick, W.N.; Krenn, M.; Schaeff, C.; Ramelow, S.; Zeilinger, A. Quantum entanglement of high angular momenta. Science 2012, 338, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.Y.; Ohmura, T. Quantum Theory of Scattering; Courier Corporation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chadan, K.; Sabatier, P.C. Inverse Problems in Quantum Scattering Theory; Springer Science & Business Media: Basel, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moiseyev, N. Quantum theory of resonances: Calculating energies, widths and cross-sections by complex scaling. Phys. Rep. 1998, 302, 212–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucher, J. Foundations of the relativistic theory of many-electron atoms. Phys. Rev. A 1980, 22, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirac, J.; Zoller, P. Preparation of macroscopic superpositions in many-atom systems. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 50, R2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heine, V.; Robertson, I.; Payne, M.C. Many-atom interactions in solids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. A Phys. Eng. Sci. 1991, 334, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W. Density functional theory for systems of very many atoms. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1995, 56, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C. Student understanding of symmetry and Gauss’s law of electricity. Am. J. Phys. 2006, 74, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nghiem, N.A.; Phan, T.V. Fractatomic Physics: Atomic Stability and Rydberg States in Fractal Spaces. Atoms 2026, 14, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms14010002

Nghiem NA, Phan TV. Fractatomic Physics: Atomic Stability and Rydberg States in Fractal Spaces. Atoms. 2026; 14(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms14010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleNghiem, Nhat A., and Trung V. Phan. 2026. "Fractatomic Physics: Atomic Stability and Rydberg States in Fractal Spaces" Atoms 14, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms14010002

APA StyleNghiem, N. A., & Phan, T. V. (2026). Fractatomic Physics: Atomic Stability and Rydberg States in Fractal Spaces. Atoms, 14(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms14010002